Abstract

Background

The habitual excessive intake of sugar (i.e., sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup), which has been implicated in the onset of diabetes mellitus, induces excessive production of glyceraldehyde, a metabolite produced during glucose and fructose metabolism, in hepatocytes, neuronal cells, and cardiomyocytes.

Main text

Toxic advanced glycation end-products (toxic AGEs, TAGE) are formed from reactions between glyceraldehyde and intracellular proteins, and their accumulation contributes to various cellular disorders. TAGE leakage from cells affects the surrounding cells and increases serum TAGE levels, promoting the onset and/or development of lifestyle-related diseases (LSRD). Therefore, serum TAGE levels have potential as a novel biomarker for predicting the onset and/or progression of LSRD, and minimizing the effects of TAGE might help to prevent the onset and/or progression of LSRD. Serum TAGE levels are closely related to LSRD associated with the excessive ingestion of sugar and/or dietary AGEs.

Conclusions

The TAGE theory is also expected to open new perspectives for research into numerous other diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Research on protein glycation (the Maillard reaction) began with the discovery of melanoidin by Maillard in 1912 [1]. The Maillard reaction was initially regarded as a browning reaction in the food chemistry field, and its effects on the taste of food have been studied. In 1968, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), an early glycation product, was first detected in the human body [2], while advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) were discovered by Cerami et al. in the 1980s [3]. The receptor for AGEs (RAGE) was cloned by Neeper and Schmidt et al. in 1992 [4], and RAGE transgenic mice were produced by Yamamoto et al. in 2001 [5]. AGE molecules, such as Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (CML) [6], pyrraline [7], and pentosidine [8], were subsequently identified, and the majority of anti-AGE antibodies used in 1996 were shown to recognize the CML structure [9]. Therefore, the concept that CML is the main structure of AGEs has spread worldwide.

However, research into various anti-AGE antibodies by our group has demonstrated that AGE structures other than CML are more closely associated with clinical parameters [10]. We reported the concept of non-CML AGEs in 1999 [10], subsequently identified a non-CML AGE that exhibited strong cytotoxicity [11, 12], and proposed the hypothesis that “toxic AGEs (TAGE)” contribute to lifestyle-related diseases (LSRD) in 2004 [13].

The significance of serum TAGE levels as a new biomarker that could aid the early diagnosis and prevention of LSRD and evaluations of treatment efficacy are described herein. Furthermore, whether limiting sugar and/or dietary AGE intake decreases the production or accumulation of TAGE, and hence, prevents the onset and/or progression of LSRD, is discussed.

AGE generation in the human body

The balanced intake of carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, vitamins, and minerals is necessary to maintain health. Glucose, a carbohydrate, cannot function properly unless it is present in the blood at appropriate levels, and protein glycation occurs continuously in the human body. HbA1c, which is used in diagnostic tests for diabetes mellitus (DM), is one of the early glycation products generated by the reaction of glucose with hemoglobin in erythrocytes [2]. AGEs are generated under hyperglycemic conditions [14,15,16,17]. We reported that α-hydroxyaldehydes (glyceraldehyde [GA] and glycolaldehyde), dicarbonyl compounds (glyoxal [GO], methylglyoxal [MGO] and 3-deoxyglucosone [3-DG]), and also fructose contribute to protein glycation [10, 11, 18, 19].

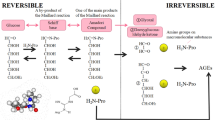

Seven immunochemically distinct classes of AGEs (glucose-derived AGEs [Glu-AGEs], fructose-derived AGEs [Fru-AGEs], glycolaldehyde-derived AGEs, GA-derived AGEs [Glycer-AGEs], MGO-derived AGEs, GO-derived AGEs, and 3-DG-derived AGEs) have been detected in sera from hemodialysis patients with diabetic nephropathy (DN-HD) [10, 11, 18, 19]. Thus, Maillard reaction, sugar autoxidation, and sugar metabolic pathways (glycolysis/the polyol pathway/fructolysis) have been proposed to be involved in AGE formation in vivo (Fig. 1). Glycer-AGEs formed from GA, a trisaccharide (triose sugar) intermediate of fructose and glucose metabolism, exhibit strong cytotoxicity [12]; therefore, we proposed the novel concept of TAGE [13]. TAGE are generated from digested starch, the main component of rice, bread, and noodles, as well as metabolites of the sugar (sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup, HFCS) added to beverages and processed foods, and fluctuations in TAGE levels are closely related to dietary habits in humans (Fig. 1).

Alternative in vivo AGE generation routes. Reducing sugars, such as glucose, fructose, and glyceraldehyde, react non-enzymatically with the amino groups of proteins to form reversible Schiff bases and Amadori products/Heyns products. These early glycation products undergo further complex reactions, such as rearrangement, dehydration, and condensation, to become irreversibly cross-linked, heterogeneous fluorescent derivatives, termed AGEs. HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; CML: Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine; GO-AGEs: glyoxal-derived AGEs; Glycol-AGEs: glycolaldehyde-derived AGEs; Glu-AGEs: glucose-derived AGEs; 3-DG-AGEs: 3-deoxyglucosone-derived AGEs; MGO-AGEs: methylglyoxal-derived AGEs; Glycer-AGEs: glyceraldehyde-derived AGEs; TAGE: toxic AGEs; Fru-AGEs: fructose-derived AGEs; AR: aldose reductase; SDH: sorbitol dehydrogenase; FK: fructokinase; P-NH2: free amino residue of a protein

Concepts of non-toxic AGEs and TAGE

It remains unclear why many types of AGEs are generated in the human body. Based on our research, in vivo AGE-generating reactions are physiologically significant because they induce post-translational protein modifications. Proteins, which are translated according to the genetic information in DNA, are responsible for various physiological processes involving post-translational modification reactions. However, in the presence of “glycation/carbonyl stress” and increased production of aldehyde/carbonyl compounds in vivo intracellular proteins can non-enzymatically react with such compounds to produce various AGEs. The generation of non-toxic AGEs, such as CML, pentosidine, and pyrraline, which do not exert direct cytotoxic effects, is a biological defense mechanism, in which proteins actively trap aldehyde/carbonyl compounds with high chemical reactivity to detoxify them. Ahmed et al. [20], who first identified CML, reported that CML is generated through an averting path. Similarly, the process that is responsible for the generation of non-toxic AGEs might be involved in the detoxification of most end-products of glycation/carbonyl stress in the human body. However, TAGE have been implicated in the pathogenesis of DM and associated vascular complications, as they bind to RAGE [21,22,23]. Interactions between extracellular TAGE and RAGE induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in numerous types of cells [23]. TAGE have also recently been implicated in cardiovascular disease (CVD), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), arteriosclerosis, infertility, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and cancer [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] (Fig. 2).

The TAGE theory of LSRD. Among the various types of AGE structures generated in vivo, TAGE, but not non-toxic AGEs, such as CML, CEL, pentosidine, and pyrraline, appear to play an important role in the pathophysiological processes associated with LSRD. We postulate that non-toxic AGE structures may be physiologically relevant for preventing the potentially damaging consequences of the advanced glycation process. CEL: Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine; MG-H1: methylglyoxal-hydroimidazolone; MOLD: methylglyoxyl-derived lysine dimer; GOLD: glyoxyl-derived lysine dimer

More recently, we demonstrated that intracellular TAGE formation and accumulation induced not only neuronal cell damage [32], but also hepatocellular damage [33,34,35] and pancreatic ductal epithelial cell damage [36], cardiomyocyte pulsation arrest and cell death [37], and myoblast cell death [38]. Therefore, TAGE are accumulate in cells, cause cell damage, and leak extracellularly into the blood, thereby increasing TAGE levels in circulating fluids.

Cytotoxicity of TAGE in the liver

According to the clinical practice guidelines for NAFLD/NASH, overeating and a lack of exercise cause non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and insulin resistance (IR), and various factors then contribute to the progression of NASH, resulting in fibrosis and potentially cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [39, 40]. Our group focused on the TAGE-RAGE axis. We reported that the addition of TAGE to hepatocytes increased IR and C-reactive protein (an inflammatory marker) levels [41, 42], while the expression levels of fibrotic markers, such as collagen type Iα2, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), were upregulated in hepatic stellate cells (HSC) [43]. We recently revealed that hepatocytes underwent necrosis and TAGE formation induced by caspase 3, which is involved in cell death [31, 34]. As a result, TAGE leaked out of the cells, affecting the surrounding hepatocytes and HSC through RAGE.

Thus, we examined the potential of TAGE leakage from damaged hepatocytes into the blood as a diagnostic marker. Serum TAGE levels were determined using a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method, involving an anti-TAGE-specific antibody developed by our group [11, 44, 45]. The epitope recognized by the anti-TAGE antibody is different from the previously reported GA-derived AGE structures; i.e., 3-hydroxy-5-hydroxymethyl-pyridinium compound (GLAP) [46] and triosidine [47]. We found that there were differences between the anti-TAGE antibody and the antibodies against well-defined AGEs as well as the antibodies against AGEs formed from reducing sugar/carbonyl molecules with unknown structures [International patent application for anti-TAGE antibody: PCT/JP2019/34,195].

Serum TAGE levels in NAFLD/NASH

NASH

NAFLD ranges from NAFL to NASH and is one of the most common causes of hepatic disease throughout the world. We assessed the serum AGE levels (TAGE, CML, and Glu-AGEs) in 66 patients that had been diagnosed with histologically verified NASH without any evidence of liver cirrhosis, 10 patients with NAFL, and 30 healthy controls [48]. The NASH patients (9.8 ± 3.7 U/mL) exhibited greater TAGE accumulation in both tissue and serum than the NAFL patients (7.2 ± 2.3 U/mL) and healthy controls (7.0 ± 2.4 U/mL). There was a positive correlation between serum TAGE levels and the homeostatic model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR), and there was an inverse association between serum TAGE levels and adiponectin levels. TAGE were also detected in the hepatocytes of NASH patients, but negligible TAGE levels were seen in NAFL patients, and no significant differences in CML or Glu-AGE levels were observed between these groups [48].

We demonstrated that hydroxymethyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor atorvastatin reduced the serum TAGE levels in 43 biopsy-proven NASH patients with dyslipidemia [49]. Following treatment with atorvastatin for 6 months (at 10 mg/day), significant reductions in liver alanine aminotransferase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) activity were seen in all patients. In addition, the patients’ plasma adiponectin levels were increased while their plasma tumor necrosis factor-α levels were decreased after the treatment. The patients’ serum TAGE levels decreased significantly during the treatment (before vs. after: 10.4 ± 3.8 vs. 5.9 ± 3.3 U/mL, respectively).

Conversely, the generation and accumulation of TAGE were detected in hepatocytes cultured under high-fructose conditions [50] and in the livers of rats reared on a high fructose and high fat diet [51] or with 10%-HFCS water [52]. Therefore, the habitual excessive intake of fructose (i.e., HFCS/sucrose/100% juices) was shown to support the formation/accumulation of TAGE in the human body.

Non-B or non-C (NBNC) HCC and rectal cancer

We previously showed that NBNC-HCC patients had significantly higher serum TAGE levels (18.2 ± 5.4 U/mL) than NASH patients without HCC (10.4 ± 3.4 U/mL) and control subjects (7.0 ± 2.4 U/mL) [53]. Multiple regression analysis demonstrated that age and γ-GTP and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (inversely) levels were significantly and independently associated with TAGE levels.

The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), which was mainly conducted in Europe and the United States, revealed that the high serum TAGE group (median value: 10.3 ± 1.7 U/mL) was at higher risk of rectal cancer after 4 years (odds ratio (OR): 1.90; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.14–3.19). Additionally, the risk of rectal cancer was even higher (OR: 2.70; 95%CI 1.29–5.62) in humans with a drinking habit (median total alcohol intake of controls: males: 18.1 g/day; females: 5.7 g/day) [54].

Sucrose/HFCS and LSRD

Previous studies have shown that the long-term consumption of high quantities of sugar also contributes to the onset and/or development of NASH, CVD, and AD; however, the responsible molecular mechanisms are yet to be discovered [55,56,57,58,59,60]. We demonstrated a strong correlation between TAGE levels and LSRD, and the habitual intake of high quantities of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) elevated hepatic GA levels. Increasing epidemiological and mechanistic evidence indicates that the effects of consuming high levels of sugar on human health cannot be explained by a simple increase in calories [61]. Sugar is known to be involved in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome-related diseases [62, 63], such as NAFLD/NASH, DM, and CVD, as well as the aging process, which is accelerated by glycation-related protein damage [14,15,16,17].

Sugar contents of commercial beverages

The American Heart Association recommended that most Americans should reduce their added sugar intake to ≤ 100 kcal-150 kcal/day (females: 25 g/day; males: 37.5 g/day) [64]. However, these values are greatly exceeded in most regions, and thus, since sugar has the same harmful effects as alcohol, sugar intake needs to be regulated [65]. The 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommended a reduction in the daily intake of added sugar to < 5% of total energy intake by adults and children (i.e., 25 g sugar for a 2000 kcal/day diet) to obtain additional health benefits [66]. We examined the sugar contents of beverages and found that approximately 40% of the 885 types of commercially available beverages in Japan contained > 25 g sugar [67].

Restricting SSB consumption

A 500-ml bottle of a carbonated beverage, such as Coke, Sprite, or Fanta, contains 50–60 g of added sugar, which exceeds the recommended daily amount of added sugar. Therefore, the WHO recommended the taxing of SSB in October 2016 [68].

We showed that in Goto-Kakizaki rats, a rodent DM model, serum TAGE levels were significantly decreased after 6 weeks’ treatment with nateglinide (a rapid-acting insulin secretagogue; 50 mg/kg, twice daily just before each meal) [69]. We also found that the serum TAGE levels, but not the HbA1c or Glu-AGE levels, of DM patients were significantly decreased after 12 weeks’ treatment with acarbose (an α-glucosidase inhibitor, 150 mg/day) [70]. These findings indicated that the habitual excessive intake of carbohydrates promotes the generation/accumulation of TAGE in the human body.

Dietary AGEs and LSRD

Two major types of AGEs, endogenous and exogenous AGEs, have been identified in humans [71, 72]. We observed elevated expression of RAGE and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in liver and accelerated TAGE formation and accumulation in normal rats that were given AGE-rich beverages in their diet [73].

AGE contents of beverages and processed foods

We assessed the concentrations of various AGEs in 885 types of beverages and 767 types of processed food that are frequently consumed in Japan. The levels of four AGEs (CML, Glu-AGEs, Fru-AGEs, and TAGE), which have been detected in the serum samples of non-DM and DM subjects, were determined employing competitive ELISA involving specific immunopurified antibodies [10, 11, 18, 19]. The assays showed that Glu-AGEs and Fru-AGEs, but not CML or TAGE, were present in considerable concentrations in the beverages and processed foods. Glu-AGEs, Fru-AGEs, CML, and TAGE were detected at levels of ≥ 85%, 2–12%, < 3%, and trace amounts, respectively, in the beverages and at levels of ≥ 82%, 5–15%, < 3%, and trace amounts, respectively, in the processed foods [74].

Restricting AGE consumption

In humans, roughly 10% of dietary AGEs (measured as the levels of CML in serum and urine after the ingestion of an AGE-containing meal) are taken into the body; one-third is eliminated by urinary excretion within 48 h of intake, and two-thirds are retained within the body [75]. We found that the serum Glu-AGE levels of healthy subjects and DN-HD ranged from 10 to 20 and from 30 to 50 U/mL, respectively. Three months’ treatment with the oral charcoal-based drug Kremezin (6 g/day) significantly decreased the serum levels of Glu-AGEs (44.1 ± 10.8 vs. 27.6 ± 6.0 U/mL) and TAGE (13.2 ± 4.4 vs. 6.2 ± 0.9 U/mL) in non-DM patients with chronic renal failure (CRF), whereas these levels remained unchanged in age- and renal function-matched CRF patients who did not receive Kremezin [76]. In addition, the Kremezin-treated patients had significantly lower serum mRNA levels of RAGE and MCP-1 and exhibited significantly lower vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression on their endothelial cells (EC) [76].

Therefore, restricting the intake of SSB/processed food-derived sugars and dietary AGEs represents a novel strategy for suppressing the generation and accumulation of TAGE and preventing LSRD.

Intracellular TAGE generation and accumulation

Using a neuronal culture system, we confirmed that TAGE are strongly neurotoxic [12, 77]. In addition, while an anti-TAGE antibody suppressed the neurotoxic effects of serum AGEs from DN-HD, no such effects were seen with antibodies against other AGEs or CML [12, 77]. In AD brains, TAGE were mostly found in the cytosol of neuronal cells in the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus, but TAGE were not present in senile plaques or astrocytes [78]. We also showed that intracellular TAGE production reduced amyloid β levels and increased total tau and p-tauT181 levels in the culture media and the intracellular levels of AD biomarkers (i.e., total tau, p-tauT181, VEGF, and TGF-β) in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells [32].

We revealed that intracellular TAGE generation/accumulation damages neurons, hepatocytes, pancreatic ductal epithelial cells, cardiomyocytes, and myoblast cells [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. The TAGE precursor GA is generated in these cells, particularly hepatocytes, via three pathways [79]: (i) Glucose is metabolized glycolytically to GA-3-phosphate, before being non-enzymatically dephosphorylated and degraded to GA; (ii) fructose is metabolized to GA via a pathway involving fructokinase and aldolase B (fructolysis); and (iii) in hyperglycemic conditions glucose is metabolized to fructose via the polyol pathway, which regulates aldose reductase and sorbitol dehydrogenase, and the resultant fructose is metabolized to GA via fructolysis.

The liver plays a major role in carbohydrate homeostasis, controlling glucose levels by synthesizing and degrading glycogen and making glucose via gluconeogenesis [80]. The liver is also generally assumed to be the primary site of dietary fructose metabolism, and fructose promotes hepatic lipid accumulation via GA. Western foods that are rich in solid fats, fatty meals, full-fat dairy products, and highly processed foods tend to be the richest dietary sources of AGEs [81]. The thermal treatment of foods might increase their digestibility, nutritional value, and shelf-life. On the other hand, the AGE-modification of essential amino acids, particularly that of lysine, might reduce the nutritional value of proteins since cross-linked proteins are less digestible [82].

The habitual intake of large amounts of sugar and dietary AGEs [67, 74], which is characteristic of the modern diet, disturbs the metabolic system in hepatocytes; induces excessive GA production, which leads to TAGE being generated from intracellular proteins; and upregulates RAGE expression. Therefore, the accumulation of TAGE in cells leads to cell damage, which can allow TAGE to escape into the blood, thereby increasing circulating TAGE levels. Interactions between extracellular TAGE and RAGE alter intracellular signaling, gene expression, and the release of pro-inflammatory molecules and also induce ROS production in several cell types [23, 29], any of which could lead to the pathological alterations seen in LSRD (Fig. 3).

In vivo TAGE generation routes. The chronic intake of excessive amounts of SSB/processed foods increases the cellular levels of the sugar metabolite GA, which induces TAGE generation from intracellular proteins. Consequently, TAGE accumulate in cells, causing cell damage, and leak into the blood, increasing circulating TAGE levels. The TAGE-RAGE axis produces ROS, which appear to upregulate RAGE expression and TAGE generation. AR: aldose reductase; SDH: sorbitol dehydrogenase; FK: fructokinase; ALD B: aldolase B; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; LSRD: lifestyle-related diseases; P-NH2: free amino residue of a protein

TAGE levels reflect the effects of not only blood glucose but also fructose and dietary AGEs, which are not reflected by blood glucose levels. Therefore, suppressing the effects of TAGE represents a novel strategy for preventing LSRD.

Serum TAGE levels and LSRD

Serum TAGE levels could be useful as a new biomarker for diagnosing LSRD early or evaluating the effectiveness of measures to prevent/treat the onset and/or development of LSRD, regardless of the presence/absence of DM.

Infertility

AGEs accumulate in DM patients and play an important role in the pathogenesis of the condition. Polycystic ovary syndrome, which is similar to DM, and aging are common causes of infertility. The associations between the serum TAGE concentration and the number of collected oocytes or rates of pregnancy were studied in people suffering from infertility. Both of these factors decrease with age, and even younger women with elevated serum TAGE levels (> 7.24 U/mL) experience reduced ongoing pregnancy rates [44]. Moreover, in women who are treated with assisted reproductive technologies (ART), correlations between serum TAGE levels and follicle development, fertilization, embryo development, and pregnancy were observed in poor responders, which suggested that TAGE accumulation is a valuable marker of fertility status that is not dependent on age or day-3 follicle-stimulating hormone levels [44].

In non-pregnant poor responders who were given sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, and underwent ART, ovarian dysfunction was ameliorated, and ongoing pregnancy rates increased significantly, in those patients whose serum TAGE levels were decreased by the sitagliptin. Pregnancy rates, both ongoing and clinical, were considerably higher in the sitagliptin-treated patients (20% and 14%, respectively) than in the controls (2.3% and 0%, respectively) [unpublished data]. Therefore, TAGE levels might be a valuable indicator that could aid the early diagnosis of ovarian dysfunction. In addition, reducing TAGE accumulation might be a novel therapeutic approach against poor ovarian responses.

CVD

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) contribute to the maintenance of endothelial structure and function, and thus, promote vascular repair and angiogenesis. Even among healthy subjects with normal blood test values, reductions in the number and activity of vascular EPC were observed in a group with high serum TAGE levels. High serum TAGE levels (> 9.20 ± 1.85 U/mL) were found to be independently associated with a reduced number and decreased migratory activity of circulating EPC in otherwise healthy volunteers (34.6 ± 6.9 years old, 40 males and 8 females) [83], suggesting that TAGE impair EC repair. In healthy volunteers (53.7 ± 7.2 years old, 15 males and 15 females) that were administered collagen tripeptide (2.4 g/day for 6 months), which inhibits TAGE formation, the cardiac-ankle vascular index, an index of blood vessel stiffness, decreased with the serum TAGE level (9.95 ± 2.96 vs. 9.25 ± 2.82 U/mL) [84]. Thus, there is a possibility that serum TAGE levels are useful as a novel biomarker not only of vascular damage, but also for predicting future cardiovascular events. Further longitudinal studies are needed to clarify whether reducing the TAGE burden using AGE inhibitors and/or restricting the consumption of sugars/dietary AGEs could protect against CVD in non-DM/DM patients.

We also demonstrated that: (i) serum TAGE levels, but not those of HbA1c or CML, were independently related to vascular inflammation, as demonstrated by [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography, in outpatients [45]; (ii) among pre-DM patients, circulating TAGE levels were significantly higher in the high mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE) group than in the low MAGE group [85]; and (iii) an association between elevated baseline TAGE levels and plaque progression in the assessment of pitavastatin and atorvastatin was found in an acute coronary syndrome trial (The JAPAN-ACS Sub-study) [86].

Non-DM/DM

DM patients were reported to have higher serum TAGE levels than healthy controls [87, 88]. We also demonstrated that serum TAGE levels, but not those of HbA1c, CML, or Glu-AGEs, were related to thrombogenic marker [89, 90], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [91], serum pigment epithelium-derived factor [92], and DPP-4 [93] levels in the general population. Furthermore, we found that circulating TAGE levels were independently correlated with the HOMA-IR index in control subjects without DM [94]. In addition, serum TAGE levels were found to be (i) associated with visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue inflammation and reduced adiponectin levels in outpatients [48, 95]; (ii) elevated in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and DM and correlated with the levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as MCP-1 [88], the soluble form of VCAM-1 [96], and asymmetric dimethylarginine [97, 98]; and (iii) correlated with the soluble RAGE level, which might reflect RAGE expression in tissues, in non-DM/DM subjects [87, 88, 99,100,101,102], suggesting that the serum TAGE level is a useful marker of TAGE-RAGE axis activation.

We observed that the circulating TAGE levels in DM patients significantly decreased (11.9 ± 3.0 vs. 8.2 ± 0.8 U/mL) after 12 weeks’ acarbose treatment [70]. We also reported that a DPP-4 inhibitor [103], sulfonyl urea [104], and insulin [105] significantly reduced serum TAGE levels, and these reductions were found to be related to decreased levels of biomarkers of organ damage in DM and CKD patients. Moreover, we demonstrated that atorvastatin reduced the serum TAGE levels of DM/non-DM CKD/acute myocardial infarction patients [106,107,108].

Serum TAGE levels might be useful for identifying high-risk patients and provide valuable information for making treatment-related decisions.

Conclusions and perspectives

The production and accumulation of TAGE in the human body, which are promoted by modern dietary habits, have important health implications. Even in healthy subjects with normal blood test values, high serum TAGE levels predict the onset and/or development of various LSRD. Therefore, the serum TAGE level might be a useful biomarker for aiding the prevention/early diagnosis of LSRD or evaluating the efficacy of treatments for LSRD (Fig. 4a, b).

Conclusions/perspectives. a TAGE are a novel target for preventing the onset and/or progression of LSRD. b The onset and progression of LSRD are associated with habitual excessive intake of sugars/dietary AGEs. c Suppressing the generation/accumulation of TAGE may prevent the onset and/or progression of LSRD. The following strategies are recommended: (i) avoid habitual excessive intake of unhealthy beverages and/or food; (ii) increase the habitual intake of Japanese foods that suppress the generation/accumulation of TAGE; and (iii) adopt a vegetables-first and/or carbohydrates-last eating order to reduce rapid increases in blood sugar levels. The maintenance of dietary habits, as described above, represents a novel strategy for achieving a healthy and long life by suppressing the generation/accumulation of TAGE in the body, which contributes to the prevention of LSRD. AD: Alzheimer’s diseases; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; HFCS: high-fructose corn syrup; LSRD: lifestyle-related diseases; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; RAGE: receptor for AGEs; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SSB: sugar-sweetened beverages; TAGE: toxic AGEs

Collectively, these findings indicate the importance of suppressing the formation and accumulation of TAGE in the human body by reducing the habitual excessive intake of sugar/dietary AGEs, as a novel way of preventing LSRD (Fig. 4c, upper). Western foods that are rich in solid fats, fatty meats, full-fat dairy products, and highly processed foods (mainly grilled, fried, deep fat fried, and roasted dishes) tend to be the richest dietary sources of AGEs [81]. On the other hand, the Japanese diet includes many low-fat foods, such as rice, seaweed, mushrooms, soy-based foods; i.e., tofu, and vegetables (especially root vegetables that are rich in insoluble/indigestible dietary fiber), and meals with low dietary AGE levels (mainly boiled and steamed dishes) [74].

The accumulation of TAGE in the kidneys might contribute to the progressive alteration of the renal architecture and the loss of renal function, such as mesangial cell and podocyte damage, in patients and rodents via various mechanisms [23]. Regularly consuming Japanese foods with low AGE levels and large amounts of insoluble dietary fiber, which absorbs and removes dietary AGEs, suppresses TAGE accumulation. The protective renal effects of Kremezin are considered to be due to its TAGE-lowering effects, which are based on the inhibition of dietary AGE absorption [76]. Therefore, the inhibition of sugar digestion and/or dietary AGE absorption by insoluble dietary fiber is a potentially useful novel strategy for preventing LSRD, such as CVD, DM, and CKD.

A vegetables-first [109, 110] and carbohydrates-last meal sequence [111, 112], followed by physical activity to promote the utilization of glucose have been recommended to prevent postprandial hyperglycemia. The consumption of vegetable or meat/fish dishes before carbohydrate dishes has also been shown to markedly improve postprandial glucose excursion in individuals with type-2 DM and healthy volunteers [109,110,111,112] (Fig. 4c, lower).

In addition to maintaining healthy dietary habits, suppressing the production and accumulation of TAGE in the body will help to prevent LSRD. The TAGE theory is also expected to open new perspectives for research into numerous other diseases.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 95%CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- AGEs:

-

Advanced glycation end-products

- ART:

-

Assisted reproductive technology

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CML:

-

Nε-(Carboxymethyl)lysine

- CRF:

-

Chronic renal failure

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- DN-HD:

-

Hemodialysis patients with diabetic nephropathy

- DPP-4:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- 3-DG:

-

3-Deoxyglucosone

- 3-DG-AGEs:

-

3-DG-derived AGEs

- EC:

-

Endothelial cells

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Fru-AGEs:

-

Fructose-derived AGEs

- EPC:

-

Endothelial progenitor cells

- GA:

-

Glyceraldehyde

- Glu-AGEs:

-

Glucose-derived AGEs

- Glycer-AGEs:

-

GA-derived AGEs

- GO:

-

Glyoxal

- GO-AGEs:

-

GO-derived AGEs

- γ-GTP:

-

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HFCS:

-

High-fructose corn syrup

- HOME-IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- HSC:

-

Hepatic stellate cells

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- LSRD:

-

Lifestyle-related diseases

- MAGE:

-

Mean amplitude of glycemic excursions

- MCP-1:

-

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MGO:

-

Methylglyoxal

- MGO-AGEs:

-

MGO-derived AGEs

- NAFL:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH:

-

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NBNC-HCC:

-

Non-B or non-C HCC

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for AGEs

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SSB:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverages

- TAGE:

-

Toxic AGEs

- TGF-β1:

-

Transforming growth factor-β1

- VCAM-1:

-

Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Maillard LC. Action des acides amines sur les sucres: formation des melanoidines par voie methodique. C R Acad Sci. 1912;154:66–8.

Rahbar S. An abnormal hemoglobin in red cells of diabetics. Clin Chim Acta. 1968;22:296–8.

Cerami A, Vlassara H, Brownlee M. Role of nonenzymatic glycosylation in atherogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 1986;30:111–20.

Neeper M, Schmidt AM, Brett J, Yan SD, Wang F, Pan YC, et al. Cloning and expression of a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14998–5004.

Yamamoto Y, Kato I, Doi T, Yonekura H, Ohashi S, Takeuchi M, et al. Development and prevention of advanced diabetic nephropathy in RAGE-overexpressing mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:261–8.

Ahmed MU, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Identification of N epsilon-carboxymethyllysine as a degradation product of fructoselysine in glycated protein. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4889–94.

Hayase F, Nagaraj RH, Miyata S, Njoroge FG, Monnier VM. Aging of proteins: immunological detection of a glucose-derived pyrrole formed during maillard reaction in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3758–64.

Sell DR, Monnier VM. Structure elucidation of a senescence cross-link from human extracellular matrix. Implication of pentoses in the aging process. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21597–602.

Ikeda K, Higashi T, Sano H, Jinnouchi Y, Yoshida M, Araki T, et al. N (epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine protein adduct is a major immunological epitope in proteins modified with advanced glycation end products of the Maillard reaction. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8075–83.

Takeuchi M, Makita Z, Yanagisawa K, Kamaeda K, Koike T. Detection of noncarboxymethyllysine and carboxymethyllysine advanced glycation end products (AGE) in serum of diabetic patients. Mol Med. 1999;5:393–405.

Takeuchi M, Makita Z, Bucala R, Suzuki T, Koike T, Kameda Y. Immunological evidence that non-carboxymethyllysine advanced glycation end-products are produced from short chain sugars and dicarbonyl compounds in vivo. Mol Med. 2000;6:114–25.

Takeuchi M, Bucala R, Suzuki T, Ohkubo T, Yamazaki M, Koike T, et al. Neurotoxicity of advanced glycation end-products for cultured cortical neurons. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:1094–105.

Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S. TAGE (toxic AGEs) hypothesis in various chronic diseases. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:449–52.

Bucala R, Cerami A. Advanced glycosylation: chemistry, biology, and implications for diabetes and aging. Adv Pharmacol. 1992;23:1–34.

Vlassara H, Bucala R, Striker L. Pathogenic effects of advanced glycosylation: biochemical, biologic, and clinical implications for diabetes and aging. Lab Invest. 1994;70:138–51.

Brownlee M. Advanced protein glycosylation in diabetes and aging. Ann Rev Med. 1995;46:223–34.

Takeuchi M, Makita Z. Alternative routes for the formation of immunochemically distinct advanced glycation end-products in vivo. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:305–15.

Takeuchi M, Yanase Y, Matsuura N, Yamagishi S, Kameda Y, Bucala R, et al. Immunological detection of a novel advanced glycation end-product. Mol Med. 2001;7:783–91.

Takeuchi M, Iwaki M, Takino J, Shirai H, Kawakami M, Bucala R, et al. Immunological detection of fructose-derived advanced glycation end-products. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1117–27.

Ahmed MU, Dunn JA, Walla MD, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Oxidative degradation of glucose adducts to protein. Formation of 3-(N epsilon-lysino)-lactic acid from model compounds and glycated proteins. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8816–21.

Sato T, Iwaki M, Shimogaito N, Wu X, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M. TAGE (toxic AGEs) theory in diabetic complications. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:351–8.

Takeuchi M, Takino J, Yamagishi S. Involvement of TAGE-RAGE system in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. J Ophthalmol. 2010;2010:170393.

Takeuchi M, Takino J, Yamagishi S. Involvement of the toxic AGEs (TAGE)-RAGE system in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular complications: A novel therapeutic strategy. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:1468–82.

Sato T, Shimogaito N, Wu X, Kikuchi S, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M. Toxic advanced glycation end product (TAGE) theory in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:197–208.

Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S. Possible involvement of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:973–8.

Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S. Involvement of toxic AGEs (TAGE) in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular complications and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:845–58.

Takeuchi M, Takino J, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Ueda T, Tsutsumi M, et al. Involvement of the TAGE-RAGE system in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Novel treatment strategies. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:880–93.

Takino J, Nagamine K, Hori T, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takeuchi M. Contribution of the toxic advanced glycation end-products-receptor axis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2459–69.

Takeuchi M. Serum levels of toxic AGEs (TAGE) may be a promising novel biomarker for the onset/progression of lifestyle-related diseases. Diagnostics. 2016;6:23.

Takeuchi M, Takino J, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Tsutsumi M. Toxic AGE (TAGE) theory for the pathophysiology of the onset/progression of NAFLD and ALD. Nutrients. 2017;9:634.

Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Takino J, Takeuchi M. The relevance of toxic AGEs (TAGE) cytotoxicity to NASH pathogenesis. Nutrients. 2019;11:462.

Koriyama Y, Furukawa A, Muramatsu M, Takino J, Takeuchi M. Glyceraldehyde caused Alzheimer’s disease-like alterations in diagnostic marker levels in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13313.

Takino J, Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi M. The formation of intracellular glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products and cytotoxicity. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:646–55.

Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Takino J, Takeuchi M. Impact of intracellular glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products on human hepatocyte cell death. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14282.

Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Takeuchi M. Intracellular toxic advanced glycation end-products promote the production of reactive oxygen species in HepG2 cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4861.

Takata T, Ueda T, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takeuchi M. Generation of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products in pancreatic cancer cells and the potential of tumor promotion. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4910–9.

Takata T, Sakasai-Sakai A, Ueda T, Takeuchi M. Intracellular toxic advanced glycation end-products in cardiomyocytes may cause cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2121.

Takata T, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takeuchi M. Impact of intracellular toxic advanced glycation end-products (TAGE) on murine myoblast cell death. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12:54.

European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–402.

Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–57.

Yoshida T, Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Matsui T, Imaizumi T, Takeuchi M, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) ameliorates advanced glycation end product (AGE)-induced hepatic insulin resistance in vitro by suppressing Rac-1 activation. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40:620–5.

Yoshida T, Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Matsui T, Imaizumi T, Takeuchi M, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) inhibits advanced glycation end product (AGE)-induced C-reactive protein expression in hepatoma cells by suppressing Rac-1 activation. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2788–96.

Iwamoto K, Kanno K, Hyogo H, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Tazuma S, et al. Advanced glycation end products enhance the proliferation and activation of hepatic stellate cells. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:298–304.

Jinno M, Takeuchi M, Watanabe A, Teruya K, Hirohama J, Eguchi N, et al. Advanced glycation end-products accumulation compromises embryonic development and achievement of pregnancy by assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:604–10.

Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Honda A, Tahara A, Nitta Y, et al. Positive association between serum level of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and vascular inflammation evaluated by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2618–25.

Usui T, Hayase F. Isolation and identification of the 3-hydroxy-5-hydroxymethyl-pyridinium compound as a novel advanced glycation end product on glyceraldehyde-related Maillard reaction. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:930–2.

Tessier FJ, Monnier VM, Sayre LM, Kornfield JA. Triosidines: novel Maillard reaction products and cross-links from the reaction of triose sugars with lysine and arginine residues. Biochem J. 2003;369:705–19.

Hyogo H, Yamagishi S, Iwamoto K, Arihiro K, Takeuchi M, Sato T, et al. Elevated levels of serum advanced glycation end-products in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1112–9.

Kimura Y, Hyogo H, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Ishitobi T, Nabeshima Y, et al. Atorvastatin decreases serum levels of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients with dyslipidemia: clinical usefulness of AGEs as a biomarker for the attenuation of NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:750–7.

Takino J, Nagamine K, Takeuchi M, Hori T. In vitro identification of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related protein hnRNPM. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1784–93.

Ebata Y, Takino J, Tsuchiya H, Sakabe T, Ikeda Y, Hama S, et al. Presence of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products in the liver of insulin-resistant mice. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2013;83:137–41.

Takata T, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takino J, Takeuchi M. Evidence for toxic advanced glycation end-products generated in the normal rat liver. Nutrients. 2019;11:1612.

Kan H, Yamagishi S, Ojima A, Fukami K, Ueda S, Takeuchi M, et al. Elevation of serum levels of advanced glycation end products in patients with non-B or non-C hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2015;29:480–4.

Kong SY, Takeuchi M, Hyogo H, McKeown-Eyssen G, Yamagishi S, Chayama K, et al. The association between glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24:1855–63.

Mucci L, Santilli F, Cuccurullo C, Davi G. Cardiovascular risk and dietary sugar intake: is the link so sweet? Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7:313–22.

Malik VS, Hu FB. Fructose and cardiometabolic health: What the evidence from sugar-sweetened beverages tells us. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1615–24.

Wang M, Yu M, Fang L, Hu RY. Association between sugar-sweetened beverages and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6:360–6.

Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathirajuet SN, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:496–504.

Malik VS. Sugar sweetened beverages and cardiometabolic health. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2017;32:572–9.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Lampousi AM, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, Schwedhelm C, et al. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:363–75.

Joint World Health Organization (WHO)/Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Expert Consultation. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases; WHO Technical Report Series, 2003;No. 916 (TRS 916). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42665/WHO_TRS_916.pdf?sequence=1.

Lee WC, Wu KLH, Leu S, Tain YL. Translational insights on developmental origins of metabolic syndrome: Focus on fructose consumption. Biomed J. 2018;41:96–101.

Mirtschink P, Jang C, Arany Z, Krek W. Fructose metabolism, cardiometabolic risk, and the epidemic of coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2497–505.

Jonson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, Howard BV, Lefevre M, Lustig RH, et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120:1011–20.

Lustig RH, Schmidt LA, Brindis CD. The toxic truth about sugar. Nature. 2012;482:27–9.

WHO guideline. Sugars intake for adults and children; 2015. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549028.

Takeuchi M, Takino J, Shirai H, Kawakami M, Furuno S, Kobayashi Y. Assessment of total sugar and glucose concentrations in commonly consumed beverages in Japan. Nutr Food Technol. 2015;1:2.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO urges global action to curtail consumption and health impacts of sugary drinks; 2016. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/11-10-2016-who-urges-global-action-to-curtail-consumption-and-health-impacts-of-sugary-drinks.

Kitahara Y, Takeuchi M, Miura K, Mine T, Matsui T, Yamagishi S. Glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products (AGEs). A novel biomarker of postprandial hyperglycaemia in diabetic rats. Clin Exp Med. 2008;8:175–7.

Tsunosue M, Mashiko N, Ohta Y, Matsuo Y, Ueda K, Ninomiya M, et al. An α-glucosidase inhibitor, acarbose treatment decreases serum levels of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Exp Med. 2010;10:139–41.

Nowotny K, Schröter D, Schreiner M, Grune T. Dietary advanced glycation end products and their relevance for human health. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;47:55–66.

Bettiga A, Fiorio F, Di Marco F, Trevisani F, Romani A, Porrini E, et al. The modern western diet rich in advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): An overview of its impact on obesity and early progression of renal pathology. Nutrients. 2019;11:1748.

Sato T, Wu X, Shimogaito N, Takino J, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M. Effects of high-AGE beverage on RAGE and VEGF expressions in the liver and kidneys. Eur J Nutr. 2009;48:6–11.

Takeuchi M, Takino J, Furuno S, Shirai H, Kawakami M, Muramatsu M, et al. Assessment of the concentrations of various advanced glycation end-products in beverages and foods that are commonly consumed in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118652.

Koschinsky T, He C, Mitsuhashi T, Bucala R, Liu C, Buenting C, et al. Orally absorbed reactive glycation products (glycotoxins): An environmental risk factor in diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6474–9.

Ueda S, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Kohno K, Shibata R, Matsumoto Y, et al. Oral adsorbent AST-120 decreases serum levels of AGEs in patients with chronic renal failure. Mol Med. 2006;12:180–4.

Takeuchi M, Kikuchi S, Sasaki N, Suzuki T, Watai T, Iwaki M, et al. Involvement of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2004;1:39–46.

Choei H, Sasaki N, Takeuchi M, Yoshida T, Ukai W, Yamagishi S, et al. Glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;108:189–93.

Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S. Alternative routes for the formation of glyceraldehyde-derived AGEs (TAGE) in vivo. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:453–5.

Jegatheesan P, De Bandt JP. Fructose and NAFLD: The multifaceted aspects of fructose metabolism. Nutrients. 2017;9:230.

Del Castillo MD, Iriondo-DeHond A, Iriondo-DeHond M, Gonzalez I, Medrano A, Filip R, et al. Healthy eating recommendations: good for reducing dietary contribution to the body’s advanced glycation/lipoxidation end products pool? Nutr Res Rev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422420000141.

Šebeková K, Brouder Šebeková K. Glycated proteins in nutrition: friend or foe? Exp Gerontol. 2019;117:76–90.

Ueda S, Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Noda Y, Ueda S, Jinnouchi Y, et al. Serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are inversely associated with the number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in apparently healthy subjects. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30:249–54.

Tomosugi N, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi M, Yonekura H, Ishigaki Y, Numata N, et al. Effect of collagen tripeptide on atherosclerosis in healthy humans. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24:530–8.

Watanabe M, Kawai Y, Kitayama M, Akao H, Motoyama A, Wakasa M, et al. Diurnal glycemic fluctuation is associated with severity of coronary artery disease in prediabetic patients: possible role of nitrotyrosine and glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products. J Cardiol. 2017;69:625–31.

Fukushima Y, Daida H, Morimoto T, Kasai T, Miyauchi K, Yamagishi S, et al. Relationship between advanced glycation end products and plaque progression in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the JAPAN-ACS sub-study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:5.

Nakamura K, Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Adachi H, Takeuchi M, Imaizumi T. Serum levels of soluble form of receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) are correlated with AGEs in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Clin Exp Med. 2007;7:188–90.

Nakamura K, Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Matsui T, Kurita-Nakamura Y, Takeuchi M, et al. Circulating advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and soluble form of receptor for AGEs (sRAGE) are independent determinants of serum monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24:109–14.

Enomoto M, Adachi H, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Furuki K, Hino A, et al. Positive association of serum levels of advanced glycation end products with thrombogenic markers in humans. Metabolism. 2006;55:912–7.

Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Takeuchi M, Enomoto M, Furuki K, Matsui T, et al. Serum level of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) is an independent determinant of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in nondiabetic general population. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:845–8.

Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Matsui T, Nakamura K, Takeuchi M, Enomoto M, et al. Low-density lipoprotein levels are one of the independent determinants of circulating levels of advanced glycation end products in nondiabetic subjects. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E12-5.

Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Adachi H, Takeuchi M. Positive association of circulating level of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) with pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) in a general population. Pharmacol Res. 2010;61:103–7.

Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Tahara A, Kaifu K, Ueda S, et al. Serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are independently correlated with circulating levels of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) in humans. Clin Biochem. 2013;46:300–3.

Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Takeuchi M, Nitta Y, Kodama N, et al. Serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are independent correlates of insulin resistance in non-diabetic subjects. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30:42–8.

Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Kodama N, Tahara A, Honda A, Nitta Y, et al. Clinical and biochemical factors associated with area and metabolic activity in the visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues by FDG-PET/CT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E739-47.

Nakamura K, Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Matsui T, Kurita-Nakamura Y, Takeuchi M, et al. Serum levels of soluble form of receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) are positively associated with circulating AGEs and soluble form of VCAM-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:52–6.

Nakamura T, Sato E, Fujiwara N, Kawagoe Y, Suzuki T, Ueda Y, et al. Circulating levels of advanced glycation end products (AGE) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are independent determinants of serum asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) levels in patients with septic shock. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:515–8.

Nakamura T, Sato E, Fujiwara N, Kawagoe Y, Ueda Y, Suzuki T, et al. Positive association of serum levels of advanced glycation end products and high mobility group box-1 with asymmetric dimethylarginine in nondiabetic chronic kidney disease patients. Metabolism. 2009;58:1624–8.

Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Nakamura K, Matsui T, Jinnouchi Y, Takenaka K, et al. Positive association between serum levels of advanced glycation end products and the soluble form of receptor for advanced glycation end products in nondiabetic subjects. Metabolism. 2006;55:1227–31.

Nozue T, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Hirano T, Yamamoto S, Tohyama S, et al. Effect of statins on the serum soluble form of receptor for advanced glycation end-products and its association with coronary atherosclerosis in patients with angina pectoris. IJC Metab Endocr. 2014;4:47–52.

Kajikawa M, Nakashima A, Fujimura N, Maruhashi T, Iwamoto Y, Iwamoto A, et al. Ratio of serum levels of AGEs to soluble form of RAGE is a predictor of endothelial function. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:119–25.

Tahara A, Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Honda A, Igata S, Nitta Y, et al. Ratio of serum levels of AGEs to soluble RAGE is correlated with trimethylamine-N-oxide in non-diabetic subjects. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2017;68:1013–20.

Sakata K, Hayakawa M, Yano Y, Tamaki N, Yokota N, Eto T, et al. Efficacy of alogliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, on glucose parameters, the activity of the advanced glycation end product (AGE)-receptor for AGE (RAGE) axis and albuminuria in Japanese type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29:624–30.

Nakamura I, Oyama J, Komoda H, Shiraki A, Sakamoto Y, Taguchi I, et al. Possible effects of glimepiride beyond glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A preliminary report. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:15.

Yanagisawa K, Ashihara J, Obata S, Wada N, Takeuchi M, Nishino Y, et al. Switching to multiple daily injection therapy with glulisine improves glycemic control, vascular damage and treatment satisfaction in basal insulin glargine-injected diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014;30:693–700.

Jinnouchi Y, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Ishida S, Jinnouchi Y, Jinnouchi J, et al. Atorvastatin decreases serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Exp Med. 2006;6:191–3.

Nakamura T, Sato E, Fujiwara N, Kawagoe Y, Takeuchi M, Maeda S, et al. Atorvastain reduces proteinuria in non-diabetic chronic kidney disease patients partly via lowering serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3:304–7.

Shimomura M, Oyama J, Takeuchi M, Shibata Y, Yamamoto Y, Kawasaki T, et al. Acute effects of statin on reduction of angiopoietin-like 2 and glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products levels in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a message from SAMIT (Statin for Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial). Heart Vessels. 2016;31:1583–9.

Imai S, Matsuda M, Hasegawa G, Fukui M, Obayashi H, Ozasa N, et al. A simple meal plan of ‘eating vegetables before carbohydrate’ was more effective for achieving glycemic control than an exchange-based meal plan in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20:161–8.

Imai S, Fukui M, Ozasa N, Ozeki T, Kurokawa M, Komatsu T, et al. Eating vegetables before carbohydrates improves postprandial glucose excursions. Diabet Med. 2013;30:370–2.

Kuwata H, Iwasaki M, Shimizu S, Minami K, Maeda H, Seino S, et al. Meal sequence and glucose excursion, gastric emptying and incretin secretion in type 2 diabetes: a randomised, controlled crossover, exploratory trial. Diabetologia. 2016;59:453–61.

Shukla AP, Andono J, Touhamy SH, Casper A, Iliescu RG, Mauer E, et al. Carbohydrate-last meal pattern lowers postprandial glucose and insulin excursions in type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5:e000440.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 25282029 and 16H01811 and by the MEXT Regional Innovation Strategy Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT designed the review and wrote the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

If the manuscript is accepted, I agree to its publication in Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeuchi, M. Toxic AGEs (TAGE) theory: a new concept for preventing the development of diseases related to lifestyle. Diabetol Metab Syndr 12, 105 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-020-00614-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-020-00614-3