Abstract

Background

Education is an important part of the work of most doctors. Clinical preceptors act as role models and supervisors. Preceptors’ quality of supervision strongly influences the learning quality of clinical interns (Bartlett et al. BMC Med Educ 20:165, 2020). To ensure a consistent approach to every preceptorship experience, the competency of clinical preceptors should be assessed to ensure that the desired outcomes are achieved. This study aims to evaluate clinical preceptors’ competency in learner-centered teaching, to provide constructive feedback to develop the preceptors’ competency and improve supervisory skills and internship quality at Kunming Medical University (KMU) in Kunming of China.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study with a quantitative self-administered online questionnaire. The convenience sampling technique was employed. In the undergraduate internship stage of KMU, clinical preceptors (N = 340) and interns (N = 487) were invited to use the augmented Stanford Faculty Development Program questionnaire (SFDPQ) (Stalmeijer et al. Med Teach 30:e272–e277, 2008), to (self-) assess the preceptor’s competency of learner-centered teaching on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Results

Two hundred twenty-eight preceptors and two hundred thirty-six interns completed the questionnaire correctly. Overall, the assessment was positive, but the preceptors’ self-assessment significantly higher than the interns’ (p < 0.00). The overall mean of each category of preceptors’ self-assessment was greater than 4.5, with no difference based on educational qualification. Male preceptors scored significantly higher in two categories than female preceptors. Preceptors under 30 years of age with less than 5 years of teaching experience rated “Teacher’s knowledge and attitude” lower than those over 40 years of age with more than 5 years of experience (p < 0.05). There were statistically significant differences in the four categories across disciplines (p < 0.05). Undergraduate interns rated “Teachers’ knowledge” as the highest category and “Learning climate” as the lowest, and interns of different genders are evaluated without distinction in all categories of SFDPQ.

Conclusions

Employing the augmented SFDPQ to evaluate learner-centered teaching competency of clinical preceptors, offers potentially useful information for delivering constructive feedback. Combining self-evaluations with learner evaluation data can contribute to exploring preceptor competency development framework to guide them in targeted learner-centered teaching skill and acquisition and improvement, finally improving the overall quality of internships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Students spend the final years of undergraduate medical education for the most part in clinical rotations in hospital settings, offering a potentially powerful learning environment because of its high authenticity and opportunities for active participation in clinical work and integrated learning of history taking, physical examination, clinical decision making and professionalism [1]. Furthermore, with the shift towards competency-based medical education programs, opportunities for participating in the clinical work environment and for performing clinical activities are crucial for medical students’ development [2]. As a result, education was already a major mission at every teaching hospital and its providers who are physicians should be good and effective teachers [3, 4]. Meanwhile, research has shown that high-quality patient care is only feasible if medical students have received high-quality teaching and good supervision in clinical practice [5, 6]. Because the preceptor acts as a role model, supervises, provides guidance and learning experiences, and facilitates the socialization and development of the preceptee into a competent professional [7,8,9]. Besides, a good internship experience lays a solid foundation for the development of professionalism throughout a practitioner’s career [10].

Therefore, to ensure the quality of clinical internships and to promote competency, doctors need appropriate tools to aid them in selecting and developing effective ways of supervising students to create an effective learning environment. Appropriate assessment of clinical teaching may guide doctors in this [11]. Assessment allows for setting a benchmark for comparison as well as for measuring the effect of change over time [12]. The research has demonstrated that the perspectives of both the students and faculty are equally important to improve the educational experience for both groups [13] and the feedback from students on clinical teachers’ performance can have mixed effects on teaching effectiveness [14].

The clinical faculty of KMU has moved toward innovative learning methods such as learner-centered teaching (LCT) in the clinical internship phrase in recent years. However qualified clinical teachers who are described as physician role models, effective supervisors, student-based and supportive individuals, assessors, planners, and resource developers [15, 16] were not holistically assessed at KMU.

Assessments need to be effective in informing clinical teachers about all important domains and in identifying individual faculty strengths and weaknesses [17]. The augmented SFDPQ was recommended for the assessment of clinical teaching skills which has strong implications for clinical teachers and faculty development [18]. Considering teacher’s knowledge and attitude are a pivotal facet of clinical teaching [19], plus extra two categories measuring “teacher’s knowledge” and “teacher’s attitude” based on the original SFDPQ and its’ validity and internal consistency reliability have been validated [20, 21]. The Stanford Faculty Development Program Questionnaire was developed at Stanford University School of Medicine based on andragogic learner-centered educational and psychological theories of learning environments [20, 22, 23] and empirical observation of clinical teaching conducted over several decades [24, 25].

This study aims to evaluate clinical preceptors’ competency in learner-centered teaching, to provide meaningful feedback to improve clinical preceptor supervisory skills and internship quality at KMU.

Research questions

-

1.

What is preceptors’ self-evaluation of clinical preceptors’ competency in learner-centered teaching at KMU?

-

2.

What is undergraduate interns’ evaluation of clinical preceptors’ competency in learner-centered teaching at KMU?

-

3.

What is the difference between the preceptors and interns’ evaluation of clinical preceptors’ competency in learner-centered teaching at KMU?

Methods

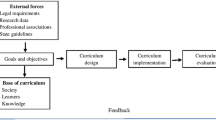

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework of this study was the Stanford Faculty Development Clinical Teaching Model [26]. The Stanford model is organized into seven key topics useful in developing excellence in clinical teaching, including learning climate, control of session, communication of goals, promotion of understanding and retention, evaluation, feedback, and promotion of self-directed learning. Based on this model and andragogic learner-centered [27] educational theories developed the Stanford Faculty Development Program questionnaire (SFDPQ) to evaluate faculty’s clinical teaching. The augmented SFDPQ complementary the teachers’ knowledge and attitude which are a pivotal facet of clinical teaching. This study chose the Stanford model as it includes nearly all aspects of clinical teaching and has been previously validated, has been widely used for faculty development and evaluation of clinical teaching excellence.

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study with a quantitative self-administered online questionnaire. The convenience sampling method was adopted. The clinical preceptors (N = 340) and undergraduate interns (N = 487) were invited to use the augmented SFDPQ to (self-) evaluate the preceptor’s competency of learner-centered teaching on a five-point scale. This study was conducted from March to June in 2023 and adopted non-probability sampling to randomly select the study population from three affiliated hospitals of KMU. The clinical preceptors (N = 340) from four disciplines (internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery, obstetrics/gynecology) made self-assessments. The undergraduate interns (N = 487) assessed the clinical preceptors who are in interns’ respective clerkship units of the department. All participants were voluntary and gave consent and were enrolled in the study.

Inclusion criteria

The clinical preceptor was identified through the preceptor list from the hospital undergraduate education department who had substantial involvement in clinical teaching during the study period. The undergraduate interns were in the fifth academic year who rotated through the units of internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery, and obstetrics/gynecology during the study period, were eligible to participate.

Exclusion criteria

The clinical faculties who were not on the preceptor’s list during the study period and the undergraduate interns who were not available during the study period were excluded from the sample.

Questionnaire, piloting, and distribution

The preceptors’ self-evaluation questionnaire was developed that consisted of two sections: section 1 is participants’ demographic data; section 2 is the augmented SFDPQ to assess the competency of learner-centered teaching. The clinical preceptors’ demographic data included gender, age, educational qualification, discipline, and teaching experience. The first section of students’ questionnaire is demographic data relating to their gender; the second section same as section 2 of preceptors’ questionnaire.

The augmented SFDPQ is the second section of the both questionnaires, which contains 9 categories, and 65 items. 9 categories including “Learning climate, Control of session, Communication of goals, Promoting understanding and retention, Assessment, Feedback, Promoting self-directed learning, Teachers’ knowledge and attitude”. Each category has 7–8 items, making a total of 65 items which were rated on a Likert five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). A score of 5 indicates an excellent demonstration of the corresponding teaching skill. Its English version was translated into Chinese and back-translated into English to check for equivalence of meaning, and also invited experts review.

Also, Piloting of the questionnaire was performed on 5 preceptors and 14 clinical interns to modify, clarify, and understand the questionnaire instructions and items, and revealed reliability of the questionnaire was acceptably good (Cronbach's alpha, 0.84). All participants who met the inclusion criteria were approached in the three hospitals by the Wechat group of the hospital’s medical education department. They received an invitation that contained the study’s objective and a QR code that led to the questionnaire page.

Data analysis

All questionnaires were conducted through ‘Survey Monkey’ online (www.sojump.com). The data was analyzed by descriptive statistics (means), independent samples t-test and One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to compare the assessments of different groups. Probability value p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed analysis) tests were considered statistically significant association for both tests. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical software SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corporation).

Results

Participants’ demographic characteristics

Out of 340 preceptors surveyed, 228 (including 120 female) valid responses were received (a response rate of 67.05%). The majority of the preceptors were between the ages of 31–40 (44.7%). 56.6% of the preceptors with doctorate Degrees and Master’s Degrees. The preceptors participated from several disciplines with internal medicine(49.1%),surgery(32.0%),obstetrics/gynaecology(16.7%)and paediatrics(2.2%). About 68.0% of the preceptors were under 15 years of teaching experience. 236 out of 487 undergraduate interns(145 female) made valid response (a response rate of 48.46%). The majority were between the ages of 21–22(76.7%).

Comparison of the overall assessment between preceptors and interns

Both the preceptors’ and interns’ assessments were positive, but preceptors rated across all categories of the augmented SFDPQ significantly higher than interns (p < 0.00). Furthermore, 64 items were statistically significant between preceptors’ and interns’ assessments (p < 0.00), except for the “Demonstrated a breadth of knowledge in medicine generally” item which did not show a statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

The clinical preceptors’ self-assessment of the augmented SFDPQ

The clinical preceptors’ self-assessments were uniformly positive across the augmented SFDPQ and the overall means of each category were more than 4.5. The “Teachers’ attitude” was the highest-rated category(4.71), and the “Teachers’ knowledge” was the lowest-rated category(4.52). The “Expressed respect for learners” was the highest-rated item(4.84) and the “Was willing to say “I don’t know” was the lowest-rated item(4.19) based on the mean (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

The undergraduate interns’ assessment of the augmented SFDPQ

Generally, the student’s overall assessment was positive and the overall means of each category were more than 4.0. The “Teachers’ knowledge” was the highest-rated category(4.28) and the “Learning climate” was the lowest (4.09). The “Revealed broad reading in his/her medical area” was the highest-rated item(4.35) and the “Was willing to say “I don’t know” was the lowest-rated item(3.84) (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

The preceptors’ characteristics and self-assessment

Based on the preceptors’ gender, age and teaching experience, Male preceptors rated the “Teacher’s knowledge” category and the “Directed students to useful literature in the field” item significantly (p < 0,05) higher than female preceptors. The older preceptors with more teaching experience rated “Teacher’s knowledge and attitude” higher than younger with less teaching experience (p < 0.05).

Regarding the educational qualification and the different disciplines, across all categories of the augmented SFDPQ, no significant differences with preceptors’ educational qualification (p > 0.05).The four categories have statistically significant difference with different disciplines (p < 0.05). The disciplines of internal medicine and pediatrics rated the “Control of session” category significantly higher than surgery and obstetrics/gynecology. The disciplines of internal medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology rated “Communication of goals” higher than surgery. On the “Teacher’s knowledge and attitude” two categories, the disciplines of internal medicine, pediatrics, and surgery are significantly higher than obstetrics/gynecology.

The interns’ demographics and assessment of the augmented SFDPQ, there was no statistically significant difference in all categories of the augmented SFDPQ based on interns’ gender (p > 0.00).

Discussion

Compare the assessment of preceptors and interns

Despite the fact that both preceptors and interns at KMU gave overall positive ratings to student-centered clinical preceptors’ competency, the preceptors’ self-assessment was significantly higher than the interns’. The preceptors gave the highest ratings in the “Teaching attitude” category and the “Expressed respect for learners” item. This finding state that self-assessments appeared to overestimate their abilities and may be confounded by respondents’ bias, which was consistent with other studies [28,29,30,31]. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to conduct a longitudinal study and multiple assessments of preceptors by peers or faculty, or by direct observation of interactions with preceptors over a long period of time [32], to providing constructive feedback, to determine which of the competencies identified are most relevant to the outcomes for interns, professional satisfaction, and career progression, all of which may indicate that the preceptorship model is successful [12].

In this study, preceptors and interns both gave the lowest ratings for “Was willing to say “I don’t know”. It suggests that many educators feel that doing so is a sign of weakness [33]. However,the lack of this competency can affect the mutual respect and communication between preceptors and learners, because once learners understand that a teacher has limitations just as they do, they begin to recognize a common ground on which to build [34]. As a result, preceptor should aware of their own limitations and take steps to improve it, and not be afraid to reveal them to learners [33].

Interestingly, the “Teachers’ knowledge” category received the lowest rating from preceptors’ self-assessment compared to interns. This could be considered an intrinsic modesty trait in preceptors who have been deeply influenced by Chinese culture, because the “Demonstrated a breadth of knowledge in medicine generally” received a similarly high rating from both groups, with no significant difference detected.Obviously, a qualitative study is necessary to investigate the preceptors’ and interns’ experience in depth and understand the factors that influenced their ratings [35]. On the other hand, this finding could also explain that the preceptors at KMU have already reflected on their weaknesses in relation to their subject knowledge and realized that effective teaching requires expertise in one’s discipline, and students want their teachers to “know their stuff” [36].

The assessment from the interns

The study results showed that interns of different genders have similar perspectives on preceptors’ teaching performance. The “Learning climate” category received the lowest rating, although hospitals’ primary activity being patient care rather than clinical teaching [1], but some studies on work-based learning show that teaching and learning in the clinical environment need to focus on creating a learning climate that provides effective learning opportunities and guidance for interns without being intimidating enough to reduce their confidence [2, 37, 38].

The self-assessment from the preceptors

The study results showed that the evaluation of internal medicine faculty was higher than that of surgical faculty on some categories. Although should be taking different assessment circumstances into account in different disciplines, but reflecting that this assessment measures what it stands for, that is teaching in the clinical environment [39]. Therefore, there should be more strengthening the development of teaching competence for surgical faculty in clinical settings.

Teachers with different educational qualification showed no difference in their self-assessments, suggests that academic medicine has assumed that talent as a clinician or the ability to teach is frequently incorrect [33]. The finding also shown that older preceptors with more teaching experience have higher rating than younger with less teaching experience on the “Teachers’ knowledge and attitude” category. Therefore, regardless of educational qualification, especially young teachers should strengthen the development of teaching competence.

Implications for clinical preceptor’s competency development

The increased social demand for excellence and the introduction of competency-based internships have heightened preceptors’ awareness of their teaching competency. Based on study findings, it is meaningful and feasible to explore a framework for competency development that enables preceptors to understand and plan their professional development. The preliminary framework includes four key domains:

-

1.

Enriching Knowledge: Provide opportunities (fellowships or teaching scholar programs) to promoting preceptors’ depth and breadth of professional and pedagogical knowledge, ensuring they stay up-to-date with developments in teaching and learning (including digital literacy).

-

2.

Skills for Establishing a Learner-Centered Learning Climate: Understand learners to create an inclusive learning environment, tailor teaching flexibly to learners’ needs (e.g., experience, competence), and provide constructive feedback (both positive and negative) to help overcome individual difficulties.

-

3.

Competency in Practice-Based Learning and Reflection: Engage in learning by doing or observing, participate in work-based learning and workshops (especially for younger preceptors with less teaching experience), develop teaching strategies for different disciplines and diverse settings, and reflect on personal strengths and weaknesses in teaching activities to meet learner outcomes.

-

4.

Authentic Professional Attitude: Conduct objective self-evaluations to serve as good role models for learners, treat all learners equitably and with respect, maintain positive attitudes towards diverse learners and patients, and demonstrate best educational and cost-appropriate care practices.

In summary, utilizing multiple evaluations and providing constructive feedback to develop competent clinical preceptors is an indispensable duty of medical universities, as preceptors contribute to excellence in medical training and patient care.

Limitation

This study was conducted at only one medical university using non-probability sampling, which may have an impact on the external validity and generalizability of the results. Another limitation is that online questionnaires produce lower response rates than paper-based questionnaires . Furthermore, the survey tool for the augmented SFDPQ was validated only through an expert review and a small sample pilot study. Finally, the study may be subject to bias because there was insufficient information to determine whether confounding factors were taken into account during the study design.

Conclusion

Employing the augmented SFDPQ to evaluate learner-centered teaching competency of clinical preceptors, offers potentially useful information for delivering constructive feedback. Combining self-evaluations with learner evaluation data can detect between-faculty differences on competency of learner-centered teaching,it contribute to exploring preceptor competency development framework to guide them in targeted teaching skill acquisition and improvement, finally improving the overall quality of internships.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Data Availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Change history

16 September 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05978-y

Abbreviations

- SFDPQ:

-

Stanford Faculty Development Program questionnaire

- SFDP:

-

Stanford Faculty Development Program

- KMU:

-

Kunming Medical University

- SCL:

-

Learner-centered teaching

References

Spencer J. Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. Br Med J. 2003;326:591–4.

Teunissen PW, Scheele F, Scherpbier AJ, et al. How residents learn: qualitative evidence for the pivotal role of clinical activities. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):763–70.

Kilminster S, Cottrell D, Grant J, Jolly B. AMEE Guide No. 27: effective educational and clinical supervision. Med Teach. 2007;29(1):2–19.

Prideaux D, Alexander H, Bower A, et al. Clinical teaching: maintaining an educational role for doctors in the new health care environment. Med Educ. 2000;34(10):820–6.

Leach DC, Philibert I. High-quality learning for high-quality health care: getting it right. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1132–4.

Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen HAP, Essed GGM, Scherpbier AJJA, Van der Vleuten CPM. Students’ perceptions of relationships between some educational variables in the out-patient setting. Med Educ. 2002;36:735–41.

Billay D, Myrick F. Preceptorship: an integrative review of the literature. Nurse Educ Pract. 2008;8(4):258–66.

Marriott J, Taylor S, Simpson M, Bull R, Galbraith K, Howarth H, et al. Australian national strategy for pharmacy preceptor education and support. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13(2):83–90.

Mills JE, Francis KL, Bonner A. Mentoring, clinical supervision and preceptoring: clarifying the conceptual definitions for Australian rural nurses. A review of the literature. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5(3):410.

Hill WT. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism: what we as pharmacists believe our profession to be determines what it is. J Am Pharm Assoc (1996). 2000;40(1):96–102.

Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH, et al. The development of an instrument for evaluating clinical teachers: involving stakeholders to determine content validity. Med Teach. 2008;30:e272–7.

Bartlett AD, Um IS, Luca EJ, Krass I, Schneider CR. Measuring and assessing the competencies of preceptors in health professions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:165.

Almulhem MA, Almulhem JA. Evaluation of problem-based learning implementation in a College of Medicine, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional comparative study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:311.

Litzelman DK, Stratos GA, Marriott DJ, Lazaridis EN, Skeff KM. Beneficial and harmful effects of augmented feedback on physicians’ clinical-teaching performances. Acad Med. 1998;73:324–32.

Harden RM, Crosby J. AMEE Guide No 20: the good teacher is more than a lecturer - the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach. 2000;22(4):334–47.

Ramani S, Leinster S. AMEE Guide no. 34: teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2008;30(4):347–64.

Smith CA, Varkey AB, Evans AT, Reilly BM. Evaluating the performance of inpatient attending physicians: a new instrument for today’s teaching hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):766–71.

Luciano GL, Carter BL, Garb JL, Rothberg MB. Residents-as-teachers: implementing a toolkit in morning report to redefine resident roles. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:316–23.

Morrison EH, Hitchcock MA, Harthill M, Boker JR, Masunaga H. The on-line Clinical Teaching Perception Inventory: a “snapshot” of medical teachers. Fam Med. 2005;37:48–53.

Litzelman DK, Stratos GA, et al. Factorial validation of a widely disseminated educational framework for evaluating clinical teachers. Acad Med. 1998;73:688–95.

Owolabi MO. Development and psychometric characteristics of a new domain of the Stanford faculty development program instrument. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2014;34(1):13–24.

Litzelman DK. Factorial validation of a widely disseminated educational framework for evaluating clinical teachers. Acad Med. 1998;73(6):688–95.

Skeff KM. Enhancing teaching effectiveness and vitality in the ambulatory setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:S26–33.

Skeff KM. Evaluation of a method for improving the teaching performance of attending physicians. Am J Med. 1983;75:465–70.

Skeff KM, Campbell M, Stratos G. Evaluation of attending physicians: three perspectives. Res Med Educ. 1984;23:277–81.

Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Berman J, Bergen MR. Improving clinical teaching: evaluation of a national dissemination program. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(6):1156–61.

Blumberg P, Pontiggia L. Benchmarking the degree of implementation of learner-centered approaches. Innov High Educ. 2011;36:189–202.

Elmore L, Blair M, Edgerton L. Preceptor development strategies used in a mixed academic-community teaching hospital. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014;6(1):167–73.

Melaku T, Srikanth A, Getaye Y, Admasu S, Alkalmi R. Perceptions of pharmacy clerkship students and clinical preceptors regarding preceptors’ teaching behaviors at Gondar University in Ethiopia. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2016;13:9.

Sonthisombat P. Pharmacy student and preceptor perceptions of preceptor teaching behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):110.

Duffy FD, Holmboe ES. Self-assessment in lifelong learning and improving performance in practice: physician know thyself. JAMA. 2006;296:1137–9.

Jahangiri L, Mucciolo TW, Choi M, Spielman AI. Assessment of teaching effectiveness in U.S. Dental schools and the value of triangulation. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(6):707–18.

Hatem CJ, Searle NS, et al. The educational attributes and responsibilities of effective medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86:474–80.

Duvivier RJ, Van Dalen J, Van Der Vluten CPM, Scherpbier AJ. Teacher perceptions of desired qualities, competencies and strategies for clinical skills teachers. Med Teach. 2009;31:634–41.

Saleh A, Bista K. Examining factors impacting online survey response rates in educational research:perceptions of graduate students. Online Submission. 2017;13(2):63–74.

Irby DM. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333–42.

Bolhuis S. Competence oriented teacher training. Old research demands and new pathways. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; 2006. p. 237–49.

Fluit C, Bolhuis S. Teaching and Learning. Patient-centered Acute Care Training (PACT). 1 ed. Switzerland: European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; 2007.

Cornelia RMG. Fluit, assessing the quality of clinical teachers: a systematic review of content and quality of questionnaires for assessing clinical teachers. Soc Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1337–45.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the faculty members who participated in the study. We would also like to thank the medical interns at KMU who participated in the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

Education and Teaching Research Project Fund of Kunming Medical University (2022-JY-Z-01), 2023 Undergraduate Education Teaching Reform Research Project Fund of Yunnan Provincial Department of Education(JG2023239), 2023 Medical Education Research Project Fund of Medical Education Branch of the Chinese Medical Association and National Center for Medical Education Development (2023B149), and 2024 Undergraduate Innovation Training Plan Project Fund of Kunming Medical University (2024CYD152)were obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenlan Zhao and Xiaohan Yin accounted for substantial the conception or design of the work, and all aspects of the work. Zixian Liu and Tong Wang contributed to analyse the data and collate the Tables and Figures of manuscript and drafting the manuscript. Yanchun Sun proposed the valuable suggestions for revised it. Siwen Wu and Bin Xu contributed to the acquisition, and interpretation of data for the work. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Kunming Medical University Research Ethics Committee; consent was obtained from all participants. All methods used to inform and develop this paper were carried out under relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tong Wang is co-first author of this article.

The original version of this article was revised: the author Tong Wang has been added as co-first author of this article. Authors Xiaohan Yin and Yanchun Sun have been added as co-corresponding authors. Additionally, spelling errors in the first and fourth affiliations have been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Wang, T., Wu, S. et al. Assessment of the competency of learner-centered teaching of clinical preceptor using the augmented Stanford Faculty Development Program Questionnaire (SFDPQ): a cross sectional comparative study. BMC Med Educ 24, 883 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05883-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05883-4