Abstract

Purpose

We examined the correlates of disability among people with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and comorbid common mental disorders (CMDs) from rural India.

Methods

The sample comprised 2,486 participants enrolled in a cluster randomized trial (cRCT), Healthier OPtions through Empowerment (HOPE). Participants were 30 years or older, with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or panic disorder on the MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, with hypertension, diabetes, dsylipidemia and/ or ischemic heart disease. Disability was measured with the 12-item version of WHODAS 2.0. The severity of depression and anxiety was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), respectively. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine associations.

Results

The mean age was 59 ± 10.0 years, three quarters (1864) of the participants were female, and 64.0% were married. More than half of the participants had no formal education (57.9%). Most of the participants had two or more chronic medical conditions (73.0%). The mean disability score was 24.3. The mean depression score was 8.5, and the mean anxiety score was 6.7. Higher levels of disability were reported by participants ≥ 60 years of age, those with moderate and severe depression, and moderate anxiety. Among female participants, being unmarried was associated with greater disability. Male participants without formal education reported greater levels of disability.

Conclusion

Higher severity of CMDs is significantly associated with higher levels of disability. For women, being unmarried and for men having no formal education was associated with higher levels of disability.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02310932 [URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02310932] registered on December 8, 2014, and Clinical Trials Registry India CTRI/2018/04/013001, registered on April 4, 2018. Retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and common mental disorders (CMDs)- depression and anxiety disorders- are among the leading causes of death and disability in India, and are increasing in prevalence. The Indian Council of Medical Research–India Diabetes (ICMR-INDIAB-17) study, a cross-sectional population-based survey which assessed a representative sample of individuals aged 20 years and older drawn from urban and rural areas, reported the overall weighted prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) at 11·4% (95% CI 10·2–12·5), hypertension (HT) at 35·5% (33·8–37·3), and dyslipidaemia (DLP) at 81·2% (77·9–84·5) [1]. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimated 23.8 million prevalent cases of ischemic heart disease (IHD) in India in 2016, 2.3 times the number from 1990, which contributed 17.8% of total deaths, and was the leading cause of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) at 8.7% [2]. Leading risk factors for DALYs attributable to IHD were high systolic blood pressure and high total cholesterol [2]. The GBD also estimated that the age-standardized DALY rate for DM in India increased by 39.6% from 1990 to 2016, which was the highest increase among major NCDs [3]. Prevalence of CMDs was also high according to the GBD, which estimated that in 2017 45·7 million people had depressive disorders and 44·9 million people had anxiety disorders [4]. The contribution of mental disorders to the total DALYs in India increased from 2·5% (2·0–3·1) in 1990 to 4·7% (3·7–5·6) in 2017, with depressive disorders contributing the most to the total mental disorders DALYs (33·8%, 29·5–38·5), followed by anxiety disorders (19·0%, 15·9–22·4) [4]. NCDs and CMDs are intimately related on multiple levels [5]. Epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate a strong association between the two groups of disorders with high rates of comorbidity [6,7,8,9]. Causal mechanisms implicated range from individual to societal, and operate bidirectionally between key risk factors, for both NCDs and CMDs [5, 10,11,12,13,14,15].

A few studies that have reported on disability in participants with NCDs and CMDs have shown a synergistic effect of the comorbidity of these health conditions on disability [16,17,18,19]. Kessler et al. [16], in a large nationally representative household survey from the United States reported on disability, mental disorders and four common chronic conditions: HT, arthritis, asthma, and ulcers. All four physical disorders were associated with significant role impairments in bivariate analyses. However, further analysis showed that these impairments were almost entirely confined to cases with comorbid mental disorders. Schmitz et al. [17], in a large nationally representative survey from Canada, reported that depression increased the odds ratio for functional disability from 2.1 in chronic conditions only to 6.3 in chronic conditions with comorbid depression, indicating a strong positive interaction. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative, a large general population survey carried out in countries in all World Health Organization (WHO) regions, also reported that the odds of severe disability among those with both CMDs and chronic physical conditions were significantly greater than the sum of the odds of the single conditions [18]. An analysis of data from the United States National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), including a nationally representative sample of 30,022 adults, grouped participants into four disease categories- no DM and no major depression, major depression alone, DM alone, and DM and comorbid major depression [19]. With no DM and no major depression as reference and after adjusting for relevant covariates, the odds ratio of overall functional disability in individuals with DM and comorbid major depression (6.15) was significantly higher than the sum of the independent odds of functional disability in individuals with DM and major depression (5.48), which again, suggests a synergistic effect rather than an additive effect. Independent of disease category, the elderly (≥ 65 years), women, people with lower household income and those with less than high school education had significantly higher odds of functional disability.

In a community sample of participants with DM, Smith et al. found an increased likelihood of reporting functional disability for participants with high anxiety or depressive symptoms or both [20]. However, there was no synergistic interaction effect of anxiety and depression symptoms on level of functional disability. Depression has also been shown to predict future disability in patients with DM. In a longitudinal study which followed up 2733 participants with DM for a period of 5 years, for participants who were not depressed at baseline, the onset and persistence of depression predicted disability at 5 years [21].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that examine the correlates of disability among people with NCDs and comorbid CMDs from low middle-income countries (LMICs), where the prevalence rates of both these health conditions are on the rise. There is also scarce research examining differences in the correlates of disability by gender. A study of these associations is relevant since differences across gender in the prevalence [22, 23], severity [24, 25], risk factors- including age and marital status [26,27,28], course [22, 23] and comorbidity [23] of CMDs are well documented in the literature. Gender-based differences also exist in the risk factors, prevalence, pattern and outcomes of NCDs [29,30,31,32,33]. This paper therefore aimed to examine the correlates of disability among people with CMDs and co-morbid NCDs from primary care in rural southern India.

Methods

Sample and study design

The data used in these analyses were from 2,486 participants enrolled in a cluster randomized clinical trial (cRCT), Healthier OPtions through Empowerment (HOPE) The objective of the trial was to examine the efficacy of the integrated management of mental health and chronic medical conditions using a collaborative care model in primary health centres (PHCs) in rural South India. The study was conducted in 49 PHCs in the rural Ramnagara district of Karnataka state in southern India. PHCs were randomly selected and were randomized 1:1 into the collaborative care and “enhanced” standard care arms. The collaborative care model consisted of two components: a clinic-based intervention and a community-based intervention, targeting the individual participants living in the catchment areas of the collaborative care model PHCs. As part of the clinic-based intervention, the participants received diagnostic testing and clinical treatment for both their mental illness and chronic disease by the PHC care team that included a physician, a nurse, and a pharmacist. All three were trained in comprehensive integrated mental health and physical health care by study-affiliated psychiatrists and community medicine physicians. During the intervention, the staff in collaborative care PHCs received support via weekly phone calls from consultant psychiatrists. The community-based intervention comprised of “healthy living” group meetings in an accessible community venue, designed to target risk factors important in the management of NCDs and CMDs. The first 12 sessions occurred weekly and were facilitated by a master’s level counsellor and co-facilitated by an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA). They were followed by nine monthly sessions in which ASHAs were encouraged to take the lead. ASHAs met with every participant’s family during bi-monthly home visits and encouraged them to support the participant’s new healthy lifestyle. The cRCT protocol has been described elsewhere [34].

Eligible participants were people living in the PHC catchment areas, 30 years or older, with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or panic disorder on the MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [35], co-diagnosed with HT, DM, and/or IHD, and able to consent to participate and be followed for 12 months. Prospective participants were evaluated for HT (elevated systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg), DM (capillary blood sugar ≥ 160 mg/dl), and angina (positive response on the Rose Angina Questionnaire) [36] and/or being on treatment for HT, DM or IHD. At least one of these diagnoses was required to be eligible for enrolment. Participants unable to provide consent due to cognitive impairment (Modified Short Blessed Cognitive Scale > 7) [37], unable to provide contact information, and those on anti-depressants at the time of initial screening, were excluded from the study. The baseline data used here were collected between May 2015 and November 2018.

Measures

All measures were collected via face-to-face interviews conducted by trained interviewers.

Disability

Disability was measured with the 12-item version of WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0), a brief, widely used assessment of overall functioning [38]. Participants mark on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 ‘None’ to 5 ‘Extreme – cannot do’ how much difficulty they had in the past 30 days with various physical (e.g. standing for > 30 min.), cognitive (e.g. learning new task) or social tasks (e.g. maintaining a friendship). There are 6 different functioning domains - cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities (household and work/school) and participation. Answers were summed over all items, as per the ‘simple scoring’ instructions in the WHODAS manual resulting in a range from 12 to 60 [38]. The WHODAS 2.0 is grounded in the conceptual framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). The ICF defines disability as “a decrement in each functioning domain” and conceptualizes disability from the perspective of the biopsychosocial model. It therefore recognizes that disability is multidimensional and is the product of an interaction between attributes of an individual and features of the person’s physical, social and attitudinal environment. In psychometric analysis the WHODAS 2.0 structure has been shown have high internal consistency [38]. In the current sample, internal consistency was α = 0.89.

Severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms

The nine-item version Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to assess severity of depression in the past 2 weeks [39]. In our sample the internal consistency was α = 0.81. Responses are measured on a 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) scale and are summed over all items. Participants were classified into minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), and severe (15–27) depression categories.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) was used to assess severity of anxiety in the past 2 weeks [40]. In our sample the internal consistency was α = 0.84. Responses were measured on a 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) scale and summed over all seven items. Participants were classified into minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), and severe (15–21) anxiety categories.

Hypertension

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) was measured using a standardized protocol. Two measurements were taken. HT was defined as showing elevated systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg on both measurements or self-report confirmed by showing a prescription or medications [41].

Diabetes Mellitus

HbA1c was selected for the measurement as it is not affected by short term dietary changes. DM was defined as HbA1c ≥ 6.5 and/or self-report confirmed by a prescription or medications [42].

Dyslipidemia

Lipids (total cholesterol, Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) and triglycerides) were measured. DLP was defined as: LDL > 190 mg/dl without DM and > 70 mg/dl with DM and /or self-report confirmed by showing a prescription or medications [43].

Ischemic heart disease

During screening, cardiac risk was assessed using Rose Angina questionnaire (RAQ) [36]. It has two parts- Part A and Part B. A positive response to either Part A or Part B was considered positive for IHD. A positive RAQ result had to be confirmed via ECG for a participant to have a diagnosis of IHD.

Chronic Medical conditions

The sum of the above dichotomous variables for HT, DM, DLP and IHD was taken to create a 1–4 variable representing the number of chronic medical conditions. As per the inclusion criteria, participants had to have at least one chronic medical condition.

Demographics

Sociodemographic variables assessed included age, gender, marital status (not married included never married, divorced/separated and widowed individuals), education status, and income.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board at St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore and Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco. Eligible participants received information about the study verbally as well as in written form including information about the intervention, study protocol, randomization process, time commitment and potential risks and benefits and provided written consent. Illiterate participants had the option of providing either verbal consent or a thumbprint. In such cases, a witness, unaffiliated with the study, also signed the consent form.

Analyses

Continuous variables were described via the mean with standard deviation, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Differences between men and women on demographic, categorical variables were tested via χ2-test. Comparison of disability, depression and anxiety score by demographic and clinical variables were performed using independent t-test and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Unadjusted and adjusted regression coefficients with 95% confidence interval were calculated using univariate and multivariate analysis, respectively. Variables that were significant in the univariate analysis, were included in the multivariate analysis in a single step. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Preliminary analysis was carried out in the entire study sample. Results showed a significant interaction of gender by marital status and gender by education. Based on our findings and significant gender differences in relation to severity of depression noted in the literature [24, 25], a further analysis was carried out stratified by gender. All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 25.0.

Results

A total of 2,678 people were eligible for the study. However, 192 did not consent, yielding a final baseline sample of 2,486. The mean age was 59 ± 10.0 years, three quarters of the participants were female, and 64.0% were married. Baseline characteristics of the participants, by gender, are presented in Table 1.

More than half of the participants had no formal education (57.9%). A large majority of participants had DM (68.6%) or HT (72.4%) while 12.9% had IHD. Majority of the participants had two or more chronic medical conditions (73.0%). More than half (65.6%) of the participants had minimal to mild depression and 25.2% had moderate depression. More than three quarters (78.7%) of the participants had minimal to mild anxiety. The mean disability score as measured by WHODAS 2.0 was 24.3 (SD = 7.7). The mean depression score as measured by PHQ-9 was 8.5 (SD = 4.1), and the mean anxiety score measured by GAD-7 was 6.7 (SD = 3.7).

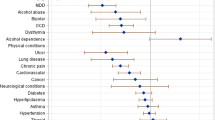

Bivariate analyses of disability scores by demographic and clinical variables are presented in Table 2. Among males and females, the mean disability score was significantly higher in participants > 60 years of age, participants who did not receive formal education, with IHD and participants who had moderate to severe depression or anxiety (all p < 0.05). In addition, among females it was noted that disability score was significantly higher in those with HT and unmarried participants.

Results from multiple linear regression analyses that included all significant variables from Table 2 as covariates are presented in Table 3, stratified by gender. In these adjusted analyses the bivariately observed associations for males regarding age, education, moderate and severe depression and moderate anxiety remained significant, but IHD and severe anxiety were not significant. Among female participants, higher age, unmarried status, moderate and severe depression and anxiety were still significantly associated with greater disability. But education, HT and IHD were no longer significant in the multivariate model.

Discussion

Higher levels of disability were reported by the elderly and those with moderate and severe depression, as well as those with moderate anxiety. In addition, among female participants, being unmarried was associated with greater disability. Male participants without formal education reported greater levels of disability.

Our finding of higher disability among older participants is in agreement with several earlier studies including from India [44,45,46,47,48,49]. Age has also been found to moderate the relationship between number of chronic diseases and physical functioning, with older participants having more physical functioning difficulties with increasing number of diseases [45, 46]. Additionally, Chou et al. found that for the NCDs included in our study, higher increments of disability occur in later stages of the disease [50], probably due to the longer duration of disease which leads to an accruement of complications. This may explain why there was no significant association between the number of NCDs and disability among our participants.

In the present study, being unmarried was associated with an increased disability score in women but not among men. This is consistent with previous epidemiological studies from rural India which demonstrate that, for both men and women as a group, being unmarried or widowed was associated with higher functional disability [46, 47]. A multivariate decomposition analysis of data from the first wave of the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India showed that marital status contributed 13% and 10% to the gender gap (women > men) in difficulty in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, respectively [51]. Marital status has also been found to moderate the influence of depressive symptoms and chronic diseases on functional limitations, for both men and women as a group [52]. In rural India, it is likely that social norms that determine gender roles and disempowerment of women [53], may have a bearing on disability. Studies from India demonstrate that nationwide, single women have low levels of empowerment, including autonomy in taking decisions regarding healthcare and accessing healthcare facilities [54], which could lead to higher levels of disability. This is especially true for widowed women [55, 56], who constituted most of the unmarried women in our sample. Additionally, our sample contained very few unmarried men (6% of men vs. 46% of women), which could at least partially explain the gender difference we found because the study may not have been sufficiently powered to detect a similar difference in men.

Having no formal education was significantly associated with disability only in male participants. This is consistent with previous research which has shown low education levels to be associated with higher disability in samples from India and abroad among both men and women [46, 51, 57, 58]. It is likely that this association between educational attainment and disability is driven by several personal and contextual factors- lower-educated men may have fewer job options, less health literacy, difficulty in effectively utilizing their social and economic resources to manage chronic diseases, resulting in higher disability.

We found that participants with moderate and severe depression and/or anxiety had significantly higher odds of disability than those reporting minimal or mild symptoms of these CMDs, which increased with increasing severity of these CMDs. The results from our study underscore the importance of the severity of depression and anxiety as correlates of disability among participants with NCDs, which, to the best of our knowledge, has not previously been reported. Disability is a multidimensional construct as shown by the results reported here. The 12-item version of WHODAS 2.0 contains six latent constructs: cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities, and participation. Studies have also demonstrated that this version of WHODAS 2.0 can represent different combinations of several contributing factors [59]. Thus, it is likely that, among our participants, NCDs and CMDs contributed differentially to the domains of disability captured by this measure, resulting in higher disability scores among participants reporting higher severity of anxiety and depression. Additionally, CMDs may interact with NCDs through complex physiological, psychological, behavioural and environmental mechanisms operating at multiple levels to cause disability [5]. For example, depression impairs cognition and motivation which in turn can interfere with vital self-care processes in diabetics, like medication adherence. This can lead to DM-related complications such as diabetic foot, which can contribute to disability. Randomized controlled trials that have examined the efficacy of interventions for CMDs among participants in primary care settings have shown positive results for reduction of disability [60,61,62]. However, randomized controlled trials that have examined the efficacy of interventions for CMDs and comorbid NCDs among participants in primary care have not demonstrated the same benefit [63, 64]. Recent studies from India that have tested the efficacy of collaborative care interventions in participants with DM and CMDs have demonstrated positive results in terms of modifying these chronic diseases that are associated with disability [65, 66].

Future research would benefit from a focus on the explication of biological and behavioral mechanisms and intermediate factors that mediate sociodemographic predictors and CMDs with disability, in patients with NCDs. It might also be useful to examine the effect of treating both comorbid CMDs and NCDs on disability within the framework of collaborative care models.

Strengths and limitations

The present study had multiple strengths, including a large community-based sample from rural India. Furthermore, in most studies on disability among participants diagnosed with NCDs and CMDs, the diagnosis of an NCD was based on the participant’s self-report [16,17,18,19,20], whereas for most of the participants in the present study, the diagnosis of an NCD was based on laboratory investigations. Geographical limitations preclude us from generalizing these findings to other regions. All the participants had CMD and NCD, therefore our findings cannot be generalized to people with only CMD or only NCD or neither condition. Finally, since the data in these analyses were cross-sectional, cause-effect relationships could not be established and need to be examined in future studies.

Conclusion

In this rural population of people with CMD and co-morbid NCD conditions, reporting moderate to severe depression and moderate anxiety levels were significantly associated with higher levels of disability. In addition, being unmarried was associated with higher levels of disability among female participants. This information provides important targets to clinicians and researchers for future interventions to reduce the burden of disability in rural India.

References

Anjana RM, Unnikrishnan R, Deepa M et al (2023) Metabolic non-communicable disease health report of India: the ICMR-INDIAB national cross-sectional study (ICMR-INDIAB-17). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 11(7):474–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00119-5

Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Sharma M et al (2018) The changing patterns of cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors in the States of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Glob Health 6(12):e1339–e1351. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30407-8

Tandon N, Anjana RM, Mohan V al (2018) The increasing burden of diabetes and variations among the States of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Glob Health 6(12):e1352–e1362. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30387-5

Sagar R, Dandona R, Gururaj G et al (2020) The burden of mental disorders across the States of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Lancet Psychiatry 7(2):148–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4

Stein DJ, Benjet C, Gureje O, Lund C, Scott KM, Poznyak V, Van Ommeren M (2019) Integrating mental health with other non-communicable diseases. BMJ 364:1295. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l295

Scott KM, Bruffaerts R, Tsang A et al (2007) Depression–anxiety relationships with chronic physical conditions: results from the World Mental Health surveys. J Affect Disord 103(1–3):113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.015

Ormel J, Von Korff M, Burger H et al (2007) Mental disorders among persons with heart disease—results from World Mental Health surveys. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 29(4):325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.03.009

Lotfaliany M, Bowe SJ, Kowal P, Orellana L, Berk M, Mohebbi M (2018) Depression and chronic diseases: co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. J Affect Disord 241:461–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.011

Patten SB, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH et al (2018) Patterns of association of chronic medical conditions and major depression. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 27(1):42–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579601600072X

Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Modgill G, Jetté N, Eliasziw M (2008) Major depression as a risk factor for chronic disease incidence: longitudinal analyses in a general population cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 30(5):407–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.001

Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A et al (2016) Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry 73(2):150–158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688

Arnaud AM, Brister TS, Duckworth K et al (2022) Impact of major depressive disorder on comorbidities: a systematic literature review. J Clin Psychiatry 83(6):43390. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21r14328

Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM (2015) State of the art review: depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens 28(11):1295–1302. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpv047

Batelaan NM, Seldenrijk A, Bot M, van Balkom AJ, Penninx BW (2016) Anxiety and new onset of cardiovascular disease: critical review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 208(3):223–231. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.156554

Karlsen HR, Matejschek F, Saksvik-Lehouillier I, Langvik E (2021) Anxiety as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of depression: a narrative review of current status and conflicting findings. Health Psychol Open 8(1):2055102920987462. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102920987462

Kessler RC, Ormel J, Demler O, Stang PE (2003) Comorbid Mental disorders Account for the role impairment of commonly occurring Chronic Physical disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Occup Environ Med 45(12):1257–1266. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44996925

Schmitz N, Wang J, Malla A, Lesage A (2007) Joint effect of depression and chronic conditions on disability: results from a population-based study. Psychosom Med 69(4):332–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31804259e0

Scott KM, Von Korff M, Alonso J et al (2009) Mental–physical co-morbidity and its relationship with disability: results from the World Mental Health surveys. Psychol Med 39(1):33–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003188

Egede LE (2004) Diabetes, major depression, and functional disability among US adults. Diabetes Care 27(2):421–428. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.2.421

Smith KJ, Schmitz N (2014) Association of depression and anxiety symptoms with functional disability and disability days in a community sample with type 2 diabetes. Psychosomatics 55(6):659–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2014.05.015

Huang H, Russo J, Von Korff M et al (2012) The effect of changes in depressive symptoms on disability status in patients with diabetes. Psychosomatics 53(1):21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2011.07.001

Kuehner C (2017) Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry 4(2):146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2

McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG (2011) Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 45(8):1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006

Pradeep RJ, Ekstrand ML, Selvam S, Heylen E, Mony PK, Srinivasan K (2021) Risk factors for severity of depression in participants with chronic medical conditions in rural primary health care settings in India. J Affect Disord Rep 3:100071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100071

Barnow S, Linden M, Lucht M, Freyberger HJ (2002) The importance of psychosocial factors, gender, and severity of depression in distinguishing between adjustment and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord 72(1):71–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00424-4

Van de Velde S, Bracke P, Levecque K (2010) Gender differences in depression in 23 European countries. Cross-national variation in the gender gap in depression. Soc Sci Med 71(2):305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.035

Bulloch AG, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Patten SB (2017) The depression and marital status relationship is modified by both age and gender. J Affect Disord 223:65–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.007

Stegenga BT, King M, Grobbee DE et al (2012) Differential impact of risk factors for women and men on the risk of major depressive disorder. Ann Epidemiol 22(6):388–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.011

Khuwaja AK, Kadir MM (2010) Gender differences and clustering pattern of behavioural risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases: community-based study from a developing country. Chronic Illn 6(3):163–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395309352255

Sharma SK, Nambiar D, Ghosh A (2023) Sex differences in non-communicable disease multimorbidity among adults aged 45 years or older in India. BMJ Open 13(3):e067994. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067994

Zhang J, Jin Y, Jia P, Li N, Zheng ZJ (2021) Global gender disparities in premature death from cardiovascular disease, and their associations with country capacity for noncommunicable disease prevention and control. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(19):10389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910389

Walli-Attaei M, Joseph P, Rosengren A et al (2020) Variations between women and men in risk factors, treatments, cardiovascular disease incidence, and death in 27 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 396(10244):97–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30543-2

Walli-Attaei M, Rosengren A, Rangarajan S et al (2022) Metabolic, behavioural, and psychosocial risk factors and cardiovascular disease in women compared with men in 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: an analysis of the PURE study. Lancet 400(10355):811–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01441-6

Srinivasan K, Heylen E, Johnson Pradeep R, Mony PK, Ekstrand ML (2022) Collaborative care compared to enhanced standard treatment of depression with co-morbid medical conditions among patients from rural South India: a cluster randomized controlled trial (HOPE study). BMC Psychiatry 22(1):394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04000-3

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH et al (1998) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59[suppl 20]:22–33. https://www.psychiatrist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/15175_mini-international-neuropsychiatric-interview-mini.pdf

Rose G, McCartney P, Reid DD (1977) Self-administration of a questionnaire on chest pain and intermittent claudication. J Epidemiol Community Health 31(1):42–48. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.31.1.42

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H (1983) Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 140(6):734–739. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.140.6.734

Ustun TB, Kostanjesek N, Chatterji S et al (2010) Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO Disability Assessment schedule (WHODAS 2.0). World Health Organization, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/52276/retrieve

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL (2002) The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 32(9):509–515. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al (2003) Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 42(6):1206–1252. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2

Kern D (2009) American Diabetes Association’s new clinical practice recommendations promote A1C as diagnostic test for diabetes. American Diabetes Association. http://www.diabetes.org/newsroom/pressreleases/2009/cpr-2010-a1c-diagnostic-tool.html Accessed 14 June 2023

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (2002) third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106(25):3143–3421. https://doi.org/10.1161/circ.106.25.3143

Taş Ü, Steyerberg EW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM et al (2011) Age, gender and disability predict future disability in older people: the Rotterdam Study. BMC Geriatr 11:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-11-22

Stenholm S, Westerlund H, Head J et al (2015) Comorbidity and functional trajectories from midlife to old age: the Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci 70(3):332–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu113

Medhi GK, Visi V, Bora PJ et al (2021) A community-based study on functional disability and its associated factors among elderly individuals in a rural setting in Northeastern India. Cureus 13(2):e13309. https://doi.org/10.7759%2Fcureus.13309

Khan ZA, Singh C, Khan T (2018) Correlates of physical disability in the elderly population of rural North India (Haryana). J Fam Commun Med 25(3):199–204. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6130166/

Vaish K, Patra S, Chhabra P (2020) Functional disability among elderly: a community-based cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care 9(1):253–258. https://doi.org/10.4103%2Fjfmpc.jfmpc_728_19

Srinivasan K, Vaz M, Thomas T (2010) Prevalence of health related disability among community dwelling urban elderly from middle socioeconomic strata in Bangaluru, India. Indian J Med Res 131(4):515–521. https://journals.lww.com/ijmr/Abstract/2010/31040/Prevalence_of_health_related_disability_among.8.aspx

Chou CY, Chiu CJ, Chang CM, Wu CH, Lu FH, Wu JS, Yang YC (2021) Disease-related disability burden: a comparison of seven chronic conditions in middle-aged and older adults. BMC Geriatr 21:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02137-6

Srivastava S, Muhammad T, Paul R, Thomas AR (2022) Multivariate decomposition analysis of sex differences in functional difficulty among older adults based on longitudinal ageing study in India, 2017–2018. BMJ Open 12(4):e054661. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054661

Kail BL (2016) Marital status as a moderating factor in the process of disablement. J Aging Health 28(1):139–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315589572

Nayak P, Mahanta B (2012) Women empowerment in India. Bull Political Econ 5(2):155–183. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1320071

Biswas CS, Mukhopadhyay I (2018) Marital status and women empowerment in India. Sociol Int J 2(1):29–37. https://doi.org/10.15406/sij.2018.02.00030

Perkins JM, Lee HY, James KS et al (2016) Marital status, widowhood duration, gender and health outcomes: a cross-sectional study among older adults in India. BMC Public Health 16(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3682-9

Lloyd-Sherlock P, Corso B, Minicuci N (2015) Widowhood, socio-economic status, health and wellbeing in low and middle-income countries. J Dev Stud 51(10):1374–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1066497

Klijs B, Nusselder WJ, Looman CW, Mackenbach JP (2014) Educational disparities in the burden of disability: contributions of disease prevalence and disabling impact. Am J Public Health 104(8):e141–148. https://doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2014.301924

Montez JK, Zajacova A, Hayward MD (2017) Disparities in disability by educational attainment across US states. Am J Public Health 107(7):1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2017.303768

Saltychev M, Katajapuu N, Bärlund E, Laimi K (2021) Psychometric properties of 12-item self-administered World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) among general population and people with non-acute physical causes of disability–systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 43(6):789–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1643416

Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM et al (2002) Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288(22):2836–2845. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.22.2836

Patel V, Weobong B, Weiss HA et al (2017) The healthy activity program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389(10065):176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6

Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N et al (2011) Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: impact on clinical and disability outcomes over 12 months. Br J Psychiatry 199(6):459–466. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092155

Von Korff M, Katon WJ, Lin EH et al (2011) Functional outcomes of multi-condition collaborative care and successful ageing: results of randomised trial. BMJ 343:d6612. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d6612

Coventry P, Lovell K, Dickens C et al (2015) Integrated primary care for patients with mental and physical multimorbidity: cluster randomised controlled trial of collaborative care for patients with depression comorbid with diabetes or cardiovascular disease. BMJ 350:h638. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h638

Ali MK, Chwastiak L, Poongothai S et al (2020) Effect of a collaborative care model on depressive symptoms and glycated hemoglobin, blood pressure, and serum cholesterol among patients with depression and diabetes in India: the INDEPENDENT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324(7):651–662. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.11747

Kemp CG, Johnson LC, Sagar R et al (2022) Effect of a collaborative care model on anxiety symptoms among patients with depression and diabetes in India: the INDEPENDENT randomized clinical trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 74:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.11.003

Funding

This research was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health [R01MH100311].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJS- Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing- original draft. DH- Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing- original draft. KS- Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing- review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration. EH- Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing- review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. MLE- Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing- review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board at St. John’s Medical College, Bangalore and Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salazar, L.J., Hegde, D., Srinivasan, K. et al. Correlates of disability among primary care patients with common mental disorders and chronic medical conditions- a cross-sectional study from rural South India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02727-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02727-w