Abstract

Purpose

Intensive care units (ICUs) have significant palliative care needs but lack a reliable care framework. This umbrella review addresses them by synthesising palliative care practices provided at end-of-life to critically ill patients and their families before, during, and after ICU admission.

Methods

Seven databases were systematically searched for systematic reviews, and the umbrella review was conducted according to the guidelines laid out by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI).

Results

Out of 3122 initial records identified, 40 systematic reviews were included in the synthesis. Six key themes were generated that reflect the palliative and end-of-life care practices in the ICUs and their outcomes. Effective communication and accurate prognostications enabled families to make informed decisions, cope with uncertainty, ease distress, and shorten ICU stays. Inter-team discussions and agreement on a plan are essential before discussing care goals. Recording care preferences prevents unnecessary end-of-life treatments. Exceptional end-of-life care should include symptom management, family support, hydration and nutrition optimisation, avoidance of unhelpful treatments, and bereavement support. Evaluating end-of-life care quality is critical and can be accomplished by seeking family feedback or conducting a survey.

Conclusion

This umbrella review encapsulates current palliative care practices in ICUs, influencing patient and family outcomes and providing insights into developing an appropriate care framework for critically ill patients needing end-of-life care and their families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This umbrella review provides a thorough overview of palliative and end-of-life care practices in an intensive care setting, drawing from a synthesis of systematic and scoping reviews. It adds to the current body of knowledge and offers valuable perspectives for establishing an effective and appropriate care framework for critically ill patients and their families facing end-of-life. |

Introduction

Palliative and end-of-life care needs in intensive care units (ICUs) worldwide are often overlooked despite being prevalent among those admitted to these units [1,2,3,4,5]. Research shows that about 88% of older individuals have at least one palliative care need [6], with neuro-ICU patients having exceptionally high rates of need at 62% [7]. Families of these patients often feel unsupported, with goals of care not being adequately discussed [7]. Many critical care settings have identified symptom management, comprehensive care planning, and family support as crucial areas where palliative care is needed [8]. One helpful tool for identifying critically ill patients with potentially unmet palliative care needs is the electronic poor outcome screening (e-POS) score [9]. About one-third of patients with low e-POS scores die within six months of ICU admission [9]. Despite these pressing needs, there remains significant variation in palliative and end-of-life care practices in ICUs across different geographic contexts [10, 11].

The symptom burden and psychosocial distress in ICUs are high, and there is a lack of regular assessment for pain and emotional needs [12]. Additionally, interdisciplinary family conferences are infrequent [13]. Palliative care referral in ICUs is significantly less for patients with non-cancer conditions compared to cancer [14]. Furthermore, there is variability among clinicians involved in end-of-life communication tasks in ICUs, leading to different outcomes depending on the clinician leading the conversation [12]. It often leads to a lack of alignment in priorities or treatment goals between clinicians, families, and patients [15]. The joint palliative care-ICU multidisciplinary rounding model has been linked to a significant reduction in ICU and hospital length of stay [16]. Additionally, among ICU patients requiring extracoroporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support, a more extended ICU stay and treatment with more life-sustaining measures was associated with fewer palliative care consult visits in the ICU [17].

A scoping literature search revealed few published palliative and end-of-life care guidelines in ICU settings. Various strategies have been used to create these guidelines, including participatory action research in Thai paediatric ICUs [18], harmonisation of published clinical practice guidelines [19], plain literature review [20], and consensus-based approaches through Delphi studies in Japan [21], the USA [22], and India [23]. These guidelines addressed components of palliative care in paediatric ICUs [18], timely utilisation of palliative care in ICUs [19], integrating national palliative care guidelines in ICU settings [20], medical decision-making on treatment limitation [21], critically ill surgical patients needing palliative care consults [22] and procedural guidelines on treatment limitation in Indian ICUs [23]. Like the Indian consensus paper [23], European guidelines have recommended integrating palliative care in clinical acute and emergency medicine, focusing on non-oncology conditions [24]. A cluster-randomised controlled study has shown that these guidelines can improve end-of-life care and increase family satisfaction [25]. However, a survey study has revealed that many healthcare providers remain sceptical about the quality and practicality of existing guidelines [26]. Some feel that guidelines restrict treatment options and interfere with the flexibility needed to provide individualised patient care. Most participants did not see a significant difference between palliative care principles and guidelines [26]. Therefore, this umbrella review aims to use evidence from systematic reviews as the foundation for developing an appropriate care framework for palliative and end-of-life care practices in ICUs. This framework could serve as a basis for future guideline development.

Methods

The review question was

“What palliative care practices are offered to critically ill patients needing end of life care and their families before, during and after ICU admission?”

The review's objectives were to assess the palliative care practices offered to patients with critical illness needing end of life care and their families before, during and after ICU admission. Additionally, the aim was to identify the factors that either facilitate or hinder the provision of such care in ICU setting. Furthermore, the review sought to establish a correlation between palliative and end-of-life care practices and patient and family outcomes. Finally, the review aimed to develop an appropriate care framework for palliative and end-of-life care practices in ICUs.

Protocol and registration

Umbrella reviews involve systematically analysing multiple systematic reviews on a specific research topic [27]. They are conducted when several systematic reviews are available on the topic, providing a comprehensive overview of the various aspects of the phenomenon being explored. However, the validity of umbrella review findings depends on the quality of the eligible systematic reviews. Biases in primary studies and systematic reviews can be compounded and challenging to clarify [27]. This review adheres to the guidelines laid out by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for umbrella reviews [28]. It has also been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), with the registration number CRD42023463718. Furthermore, a comprehensive methodology protocol for this review has been published separately to provide detailed insights into the process [29].

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this umbrella review, outlined in supplementary File 1, encompassed systematic and scoping reviews focusing on adults receiving ICU treatment and their families. The included reviews addressed diverse demographics, individuals of all genders, ethnicities, and geographic locations, regardless of the disease conditions. The scope of the umbrella review extended to various critical care settings, including multidisciplinary or disease-specific ICUs, high-dependency units (HDUs), or areas within hospitals designated explicitly for critical care. Furthermore, we focused on systematic reviews discussing hospital-based specialist palliative and end-of-life care practices before, during and after ICU admissions, as detailed in supplementary File 2. The systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis, qualitative systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and mixed-method reviews were included. However, reviews without any search strategy or synthesis of findings, reviews exclusively involving paediatric and neonatal age groups, and reviews focusing on formal or paid caregivers were excluded. Additionally, reviews on acute care administered in a hospital ward setting, homes, or facilities not classified as ICU or HDU settings were excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

We conducted an extensive search of seven electronic databases, including the Cochrane Library, SCOPUS (Elsevier), Web of Science (Clarivate), EBSCO (CINAHL Complete), Medline (PubMed), EMBASE, and PsycINFO (Ovid), from their inception to November 30, 2023. No grey literature included in systematic or scoping reviews covered in this overview was explicitly searched for. As provided in supplementary File 3, our search strategy utilised free-text and thesaurus terms specific to the databases we explored, including MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. We combined these terms using Boolean operators (OR, AND) and did not impose any limitations on the search by specific dates or use database-specific filters. The search conducted on Medline (PubMed) can be found in supplementary File 4.

Study selection

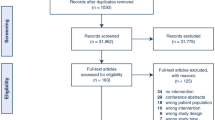

After eliminating duplicate entries in the Rayyan software [30], the records underwent a thorough two-step screening process. In the first stage, two reviewers (MM and AP) independently evaluated each article's titles and abstracts based on predetermined eligibility criteria. Relevant citations from this initial screening were retrieved in total. In the second stage, two reviewers examined the full texts to ensure they met the eligibility criteria. Any disagreements on eligibility were resolved through consensus between the reviewers or with the assistance of a senior reviewer (NS and VSD) if necessary. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart [31] (Fig. 1) illustrates the outcomes of the database search, screening process, and reasons for exclusions during the full-text review.

Data extraction

The findings of the selected reviews were extracted by independent reviewers MM and AP. In the event of discrepancies, a discussion facilitated by NS and VSD led to a consensus. We created a customised JBI data extraction template designed explicitly for umbrella reviews. We collaborated with subject expert NS to reduce errors and conducted a pilot exercise to adjust the data extraction form. The reviewers discussed the approach, testing specific items to ensure it aligned with the review objectives, and they retrieved relevant data in sufficient detail. Data was systematically extracted as sections. In the initial section on review characteristics, we recorded author details, publication year, review type, objectives, country, and setting. It was followed by a section on methodological attributes that covered eligibility criteria, reporting guidelines, databases searched, timeframe, screening methods, data extraction, risk of bias, quality assessment tools, and review synthesis methods. The final findings section included information on the number of studies, quality of evidence, quantitative and qualitative data on palliative and end-of-life care practices, barriers and facilitators, patient outcomes, Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) assessment of the quality of evidence, review limitations, conclusions, and funding.

Quality assessment

Systematic and scoping reviews underwent an evaluation for methodological quality by two independent reviewers (MM and AP) using the JBI critical appraisal checklist [32]. In cases where discrepancies arose between the reviewers, they were resolved through discussion or by seeking input from a third reviewer (NS and VSD). Data was collected for 11 specific items, and the quality of each included review was assessed using the JBI critical appraisal checklist [32] for systematic reviews and research syntheses. Each review was evaluated based on specific criteria, with responses categorised as yes, no, unclear, or not applicable. Each systematic review was classified as high quality (10–11 points), moderate quality (7–9 points) and low quality (4–6 points) based on the classification provided by Neuyen et al. [33]. However, three items on the JBI checklist (items 5 and 6 on the appraisal of studies and item 9 on publication bias) were not applicable for scoping reviews. To maintain uniformity in assessing the quality of reviews, the full score (1 point) was awarded to items that were not applicable in reviews. Moreover, we included all reviews regardless of their quality. Most included reviews did not report the certainty of evidence (GRADE), except for one review [34], and the GRADE quality score for each outcome was low to very low. An overall assessment of the certainty of the evidence using GRADE was not feasible. The outcomes of quality assessment are presented in the results section and supplementary File 8.

Data synthesis and analysis

The narrative synthesis method combined the qualitative and quantitative reviews [35]. Initially, a preliminary synthesis was created by providing a concise textual overview of the systematic reviews included in the umbrella review. This approach allowed the reviewers to familiarise themselves with the data before conducting the analysis. The interconnections between the reviews were examined by organising the review findings into meaningful categories and themes [35]. To ensure the reliability of the synthesis, the reviews were critically appraised, as discussed before [28], and the synthesis process was carefully considered.

The characteristics of this review are presented as a table, along with a narrative explanation and descriptive statistics. To focus on palliative and end-of-life care practices, a classification framework was developed based on previous guidelines from the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine (ISCCM) [36, 37], and outcomes were recorded for each practice. The purpose of identifying these practices was to develop key search concepts that became search terms for the review. Factors that impacted these practices, acting as both barriers and facilitators, were organised into themes and then into overarching groups in line with a previously published methodology [38]. The framework used in this synthesis is available in the protocol that informed this review [29]. Palliative care practices in the ICU were identified by focusing on key drivers, including prognostication, communication, decision-making, care planning, care facilitation, and care evaluation [39]. These themes and several contributing categories informed this umbrella review. Additionally, new categories were generated during data synthesis, indicating that the synthesis was not limited to the framework developed for the review.

Appropriate care concept

According to an integrative review [40], the appropriate care concept (ACC) encompasses five notions. The care must be evidence-informed, delivered by a team with clinical expertise, and patient and family-centred, enabling optimal utilisation of resources and promoting equity. Evidence-based care focuses on achieving positive health outcomes and implementing evidence into practice. A skilled clinical team has the necessary expertise and training to incorporate expert opinions into clinical decisions, allowing for customised treatment of individual patient cases. Patient and family-centred care entails offering responsive, coordinated care and promoting patient autonomy through open communication and shared decision-making. Resource management includes minimising wastage and avoiding unnecessary interventions, ensuring efficient resource allocation, and reducing costs. Equity involves the fair distribution of resources across settings to enable uniform health outcomes and non-discriminatory care. The ACC lens was used to interpret the review findings and develop an appropriate care framework for critically patients needing end of life [40].

Results

The search on databases yielded a total of 3122 records. Subsequently, these records were imported into Rayyan for deduplication and screening, and 1395 duplicate entries were removed. The title and abstracts of the remaining 1727 reviews were independently reviewed by two authors, excluding 1459 reviews unrelated to the review’s eligibility criteria. The remaining 268 search records underwent a full-text screening process, with an additional exclusion of 228 reviews not meeting the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 40 papers remained for the final analysis and synthesis. The reviews during full-text screening were excluded based on settings other than peri-intensive care setting, meaning care before, during and after ICU admission (n = 81), reviews that were not done systematically, meaning reviews without a search strategy or synthesis (n = 48), language other than English (n = 12), population other than adults (n = 13), not focused on end-of-life care or palliative care practices (n = 74). The selection process is illustrated as a PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

The characteristics of the systematic reviews incorporated into the analysis are provided in Table 1. The countries included in the review are illustrated as a map in Supplementary File 5, and a description of each systematic review included in the umbrella review is provided in supplementary File 6. Supplementary File 7 provides a view of the country of origin of systematic reviews, and Fig. 2 provides a year-wise distribution of published systematic reviews.

Year-wise distribution of published systematic reviews. This figure illustrates the distribution of review publications by year, revealing a peak in 2016 with eight publications, making up 21% of the total. This is followed by 2022 with seven publications, and 2019 and 2020 contribute six publications. All the included reviews were published between 2011 and 2023

The quality of each systematic review included in the synthesis was evaluated using an 11-item JBI critical appraisal checklist [32] provided as supplementary File 8. Of the included reviews, 28 (22 systematic and six scoping reviews) were high quality. The remaining eleven reviews (nine systematic and two scoping reviews) were of moderate quality. One review was of poor quality. The reviews have not been excluded based on their methodological quality. Most of the reviews had a specific review question and objectives (Q1), defined inclusion criteria (Q2) and search strategy (Q3). Thirty-five reviews had searched at least three databases (Q4). Among the 40 reviews, seven systematic reviews [41,42,43,44,45,46,47] did not have a critical appraisal (Q5). There were eight scoping reviews [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Although quality assessment is not a requirement in scoping reviews, two reviews [52, 54] assessed the methodological rigour of the included studies. The preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIOR) checklist is provided in supplementary File 9. Table 2 provides information on palliative and end-of-life care practices in ICUs and their outcomes. It is visually represented in Fig. 3.

Prognostication

In a few systematic reviews [41, 45, 46, 56,57,58], prognostication and prognostic communication were described as a palliative care practice within the ICU. It encompassed ICU physicians with proficiency in prognostic estimates [45, 56], creating a trigger-based palliative care referral system based on predictive estimates [41, 57] and using prognostication scales [56]. Proficiency meant the ability of the ICU physician to intuitively recognise a patient who might benefit from palliative care in the early phase of ICU management [45, 56]. Palliative care integration in ICUs enabled ICU physicians to readily recognise end-of-life phase and palliative care needs [57]. While communicating with surrogates, ICU physicians used numerical prognostic estimates, diagrams and radiographs to predict outcomes and survival [56]. Predictive estimates in medical and surgical ICUs to trigger palliative care referral relied on age, comorbidities, length of ICU stay, days on mechanical ventilation and presence of cancer and chronic illnesses leading to end-stage organ impairment [41, 57].

Involvement of experienced clinicians in prognostication and using prognostic scales improved clinical prediction, and when ICU physicians were proficient in prognostication, they could quickly recognise the need for palliative care [56] and the end-of-life phase [58], which facilitated shared decision-making [45, 56], enhanced access to palliative care [58], reduced ICU stay, and improved family satisfaction with care [41]. On the other hand, physicians' lack of understanding about prognostics impeded timely referrals to palliative care [46] and left families dissatisfied with the communication they received [41]. Furthermore, a want of prognostic skills resulted in patients receiving inappropriate care in the ICU, leading to family disappointments [58].

Communication

Communication as a palliative care practice in ICU settings was described in most systematic reviews [34, 41, 42, 44,45,46, 48, 49, 53, 54, 56, 57, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. It embodies conducting family meetings [42, 45, 46, 49, 57, 65, 68], having serious illness conversations [45, 53, 54, 56], and using information tools for communication [34, 41, 61, 65].

Family meetings are effective when it is scheduled early [48], proactively [44] and within 72 h of ICU admission [66]. Moreover, family-centred conferences [49, 57, 64, 68] and family counselling interventions [49, 51] in ICUs can be nurse or social-work-led, and they can act as communication facilitators, which could be an alternative to physician meetings [67]. Providing patients and their families with complete and timely information during these meetings in the ICU can improve shared decision-making opportunities [61, 63]. It can result in reduced anxiety and psychological distress [45, 56]. Family meetings in ICUs provide better family-centred support [68] and caregiver satisfaction [45, 65, 68] and foster agreement between ICU providers and families [48]. Failure to do so can lead to conflicts regarding prognosis and patient management [61], and families dislike poor communication, incomplete information, and short engagement during family meetings [45].

For serious illness conversations to be beneficial, they must be timely [61] and culturally sensitive [60]. The ICU physicians conducting serious illness conversations with patients and families should be trained in communication skills, planning and scheduling these meetings, and preferably, they can use nurses and social workers as liaison support [48, 57]. Serious illness conversations decreased ICU deaths and the average length of stay in the ICUs [44, 48, 66]. However, serious illness conversations that were not open and clear resulted in families feeling unprepared for the death of their loved ones [61]. It led to negative feelings about the death of their loved ones, provoking anxiety, anger and distress [61]. Physicians who were uncomfortable discussing treatment limitations [54] or handling culturally diverse families [60] impeded these conversations. Lack of cultural competency and inability to handle requests for nondisclosure of information often led to needless prolongation of life-sustaining treatments and health-related suffering [60].

The ICU teams used printed family information leaflets [68], information brochures and booklets [41, 57], resuscitation documents [34] and others like the PACE (Psychological Assessment and Communication Evaluation) and the VALUE communication tool [65] to aid conversations in the ICUs. The PACE tool led to higher satisfaction with the assessment and treatment of symptoms, while the VALUE tool resulted in more frequent family updates, increased nurse participation, and better documentation of treatment goals. These enabled families to be prepared and agree on a plan of care [48]. Communication aids improved documentation of end-of-life care, decision-making, and resource utilisation [34]. It facilitated better inter-team communication [52], effectively conveyed intentions of care to the other members of the team [34] and enabled nurses to communicate effectively in the ICU [59].

Decision-making

Most systematic reviews included in the umbrella review discussed the practice of decision-making processes in the ICU setting [43,44,45,46,47, 51, 55,56,57, 59, 62,63,64,65, 67, 69, 70]. The decision-making process involved multidisciplinary teams engaging in inter-team discussions before eliciting the goals of the care discussion with the family [51, 56], a process of collaborative decision-making between ICU teams and families [45, 46, 59, 62,63,64, 70], and using decision-making aids [34, 63, 65, 69].

Disagreements among healthcare providers regarding goals of care were frequently observed [50], resulting in needless and prolonged intensive care interventions [56]. Additionally, conflicts and disagreements between physicians and family members regarding goals of care posed a significant barrier to integrating a palliative approach in the ICUs [56]. Furthermore, insufficient clarity and inadequate assessment by healthcare providers resulted in ill-informed and misguided decision-making, which has been linked to a reduction in overall family satisfaction [42]. Therefore, inter-team discussions on prognosis, futility, benefits versus harm and future management [51, 56] were helpful, reducing decision-making conflicts [55].

According to review findings, family meetings in an ICU setting are effective when the conversations are led by a team proficient in communication skills [63]. Involvement of a senior physician [54], skills in crisis communication [46], clarity of prognosis [46], timely identification of next of kin or surrogates [65] and the use of principles of advanced care planning [63] during family meeting improved end-of-life decision-making in the ICUs. Involving families during comprehensive care planning [44, 56], discussing treatment options, and estimating survival time during family meetings reduced decisional conflict, shortened ICU stays, and aligned family and physician preferences [44, 45, 57, 63, 64, 67]. However, neglecting family involvement in decision-making leads to conflict [46]. Moreover, nurses often feel left out during family meetings [56].

Review findings support using decision-making aids [34, 65], written documents [63], educational videos [34], video-based decision-support tools and verbal descriptors [69]. It bettered ICU physicians’ familiarity with decision-making [58], promoted shared decision-making, reduced ICU costs and length of stay and instilled confidence among family members [65]. It also decreased disagreements during decision-making [55] and helped families to make decisions consistent with physician prognosis [46].

Care planning

Most systematic reviews included in this umbrella review described findings to suggest care planning as a vital practice in critically ill patients in ICUs [34, 43,44,45, 47, 51, 53,54,55,56,57, 61,62,63,64, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. It involved having a consensus-based anticipatory care plan [43, 51, 54, 56, 63, 66] and making a palliative care referral [34, 56, 66, 68, 71]. There were more studies on care planning and facilitation in this review, corresponding to more primary research conducted in these areas in the ICU setting than in others.

The consensus-based anticipatory care plan involves eliciting the family's understanding of the care process, discussion and documentation of the nature of care and resuscitation preferences [55, 69]. The presence of Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation (DNAR) orders in the ICU has become a widely accepted contemporary practice [54, 55, 69, 72, 74]. It is commonly acknowledged that withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining therapies may be necessary if deemed non-beneficial or potentially inappropriate [53, 54, 57, 61, 62, 71,72,73,74]. The results of this review reinforce the notion that patients with low-performance status and multiple medical comorbidities should be considered for anticipatory care planning when determining the extent of life-sustaining treatments [74] and that needless life-prolonging therapies should be discontinued [64]. DNAR orders often result from collaborative goal-setting and shared decision-making between healthcare providers, patients, or surrogates and are an integral component of care planning [44, 57]. Moreover, incorporating DNAR orders in the ICU is often considered a hallmark of high-quality care in critical care settings [44, 74].

Lack of care planning often leaves families unprepared for decision-making, resulting in conflicting treatment intents and a focus on life preservation [42, 43]. Lack of information, misconceptions, and healthcare providers' support or encouragement can also hinder care planning [55]. It is not uncommon for families to experience a sense of guilt, distress, and abandonment when discussing an anticipatory care plan [55]. Moreover, some clinicians consider withholding and withdrawing as ethically distinct, which might hinder treatment limitations in the ICU [54].

Review findings support proactively [67] involving palliative and supportive care services as part of the ICU care planning [34, 56, 66, 68, 71] as it betters interdisciplinary support for decision-making [46, 51]. It promotes patient-centric care, shortens ICU stays, and boosts family satisfaction [54, 56, 66, 68]. Patients with advanced cancer who didn't receive palliative care consultation were more likely to require mechanical ventilation [75], and one review revealed that palliative care is seldom considered in burns ICUs [76].

Care facilitation

This review has identified vital practices facilitating palliative and end-of-life care in ICUs [34, 41, 42, 44,45,46,47, 49, 51, 53, 54, 56,57,58,59, 61,62,63,64,65,66, 68, 71, 73, 75, 77,78,79]. It includes having institutional guidelines and policies on treatment limitation and end-of-life care [54, 56, 71], symptom management and psychosocial support [54, 57, 61, 62], withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments [68], optimising artificial nutrition and hydration [68], after death care and bereavement support [44, 49, 51, 54, 61, 66, 77] and training ICU providers in palliative care [41, 51, 56, 57, 59, 64].

In the context of end-of-life care in ICUs, ethical considerations play a crucial role [47, 53], and institutional policies on treatment limitations must be underpinned by ethical frameworks [47]. Healthcare professionals should seek clinical ethics consultation when faced with complex decision-making [34, 41, 44, 65, 66, 68]. Legal considerations are also integral; physicians must stay informed of contextual legal details [58, 63]. The misconception that the law prohibits the withdrawal of mechanical ventilation often stems from a poor understanding of legal provisions [58]. Legal concerns notably influenced physicians' decisions to issue or acquire a do-not-resuscitate order [58]. Without adequate knowledge of ethical and legal issues surrounding end-of-life decisions, the delivery of palliative care in ICUs may be impeded by uncertainty [58]. Institutional guidelines promote comprehensive care documentation [47, 54, 56, 75], but the lack of specific protocols for end-of-life care within ICUs [59, 79] impedes care. Moreover, a systematic review has raised doubt over the reliability and interpretability of clinical signs used in determining futility and end-of-life phase, leading to scepticism towards such guidelines [71]. Furthermore, a lack of awareness or resistance to adhering to these guidelines can hinder providing optimal end-of-life care in ICUs [56].

Effective pain and symptom management during end-of-life care is essential to quality care [54, 57, 61, 62]. ICU providers should receive training in using validated scales for symptom assessment and administering opiates to manage symptoms [71, 73]. The absence of palliative care and pain management protocols within the context of end-of-life care in ICUs can impede the care process [73]. Additionally, inadequate guidance on managing symptoms such as dyspnoea during mechanical ventilation withdrawal can cause distress for families [47]. The systematic review results underscored the importance of upholding patients' dignity in the ICU by honouring their preferences [45, 46, 59, 61] and offering personalised care [45, 59]. Sharing written documentation with families regarding end-of-life care [64] and allowing families to be present during treatment limitations and the dying process can be beneficial [45, 64, 77]. Additionally, providing spiritual support to families [45, 57, 59, 75], establishing a spiritual support system within the ICU [42, 64], and promoting communication to address spiritual and existential distress [59] were valuable.

The review findings suggest that offering care immediately after death and bereavement support are crucial initiatives. However, limited access to spaces for grieving at the ICU bedside poses a significant challenge [61]. It was found that integrating the mortuary team into the multidisciplinary team could help provide after-death care [51]. Additionally, creating a family bereavement support system [54, 66] and providing printed bereavement documents such as condolence letters, brochures, pamphlets, and diaries were deemed valid [44, 45, 49, 77]. The review findings also highlighted the importance of recognising post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression among bereaved family members [44, 49] and using validated tools to screen for them [77].

The findings of this review suggest that ICUs must have the capacity to provide end-of-life care. One way to enhance this capacity is by educating ICU providers and medical and nursing staff [41, 51, 56, 57, 59, 64]. Initiatives to educate nursing staff on end-of-life care interventions have improved their ability to provide quality care [42, 57, 59]. Simulated learning using case scenarios was found to be helpful [57]. In contrast, the absence of education initiatives has been found to limit their capacity to do so [56].

Care evaluation

Eight systematic reviews [42, 49, 51, 53, 56, 57, 62, 64, 65] discussed formal and informal evaluations of end-of-life care in ICUs. Care was evaluated using family feedback as a surrogate marker of the care provided. The bereaved family members completed care of the dying evaluation or quality of death questionnaires during a survey or participated in a qualitative interview to formally assess end-of-life care in the ICUs. Likewise, informally, during bereavement support, views of families on the care provided in the last days of life were explored.

Ensuring family satisfaction with end-of-life care is crucial in an ICU setting [42, 56, 64]. Families perceived positive dying experiences as being associated with patient comfort [62], the presence of family during the dying process, the perception of nursing expertise, support in decision-making, and documentation of end-of-life wishes [64]. Moreover, access to appropriate resources, including chaplaincy and other support personnel, bettered satisfaction [60]. Family-centred care and physician-led conferences also contributed to family satisfaction [42, 49, 56, 57]. Implementing strategies to reduce the duration of ICU stays [53, 65] and providing decision-making support [65, 67] yielded cost-saving advantages, improving family satisfaction. The unmanageable expenses associated with medical care in ICUs exacerbate families' financial and emotional stress [53]. The perceived high cost of treatment may lead some to question its necessity, further compounding the burden on families [53].

Likewise, limited bed availability, space, high occupancy levels, insufficient means of providing comfort, and lack of privacy negatively impacted family satisfaction [79]. The families unprepared for the unpredictability of the end-of-life process, uncertainty about the timing of events, and signs of respiratory distress following the removal of mechanical ventilation led to dissatisfaction [62]. Additionally, families were dissatisfied with inconsistent and contradictory information provided by physicians, lack of clarity, holistic assessment, and poor timing and frequency of physician communication, which can lead to uninformed decision-making [42, 56]. Moreover, unwelcoming and uncomfortable ICU waiting rooms, lack of private space for communication, and inflexible visiting hours can also contribute to dissatisfaction [42, 52, 80].

Various methods, such as surveys, scoring systems, and interview-based studies, have been used to assess care evaluation in ICUs [51, 64]. Care evaluation scales, good death inventory, quality of death and dying (QODD), family satisfaction ICU (FS-ICU) and Evaluation of Experiences of Withdrawal Tool were some of the scales and tools used to evaluate the care of the dying from the perspective of the family [64]. However, using quantitative instruments for assessing services may not fully capture the intricacies of care, and evaluations may be influenced by the biases of the self-selecting group participating in these assessments [51].

Discussion

The lenses of appropriate care concept [40] discussed in the methods section was used to interpret the review findings. Care is appropriate when it is evidence-based, delivered by a professional team with the requisite expertise, with a patient and family focus, enabling optimal usage of resources and promoting equity [40].

Several palliative and end-of-life care practices described in this review highlighted evidence-based approaches like prognostic estimates based on tools and models informing decision-making. Evidence-based practices like neuro-prognostication in cases of hypoxic brain injury [81] and prediction approaches like the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, Simplified Acute Physiology Score, and Mortality Probability Models were valuable in ICU care [82]. Evidence-based decision-making tools were helpful in randomised controlled trials involving Australian ICUs, where families reported feeling included in the decision-making process [83].

The significance of physicians' proficiency in prognostic estimates and clinical prediction and timely and effective communication of prognosis to facilitate informed decision-making and care planning could be an example of a team’s expertise. Implementing a structured process that fosters inter-team collaboration and shared decision-making by eliciting care goals was identified as a helpful practice in this review. A proficient team must facilitate a shared decision-making process through effective exchange of information, thoughtful deliberation, and, ultimately, a treatment decision [84]. Facilitating paced reflection, iterative thinking, and careful information sharing effectively promoted shared decision-making [85]. Evidence from this review supports the view that excellent care planning reflects team expertise. The findings mirror a study conducted in the United States, where comprehensive care planning in ICUs involves ethics consultations, family education, proactive involvement of a palliative care team, goals-of-care discussions, and advance care planning [57]. However, it should account for contextual factors, disease stages, potential treatments, possible outcomes, medications, and management of complications [86]. Moreover, review findings recommend that ICU teams must have expertise in managing end of life symptoms, as most patients in intensive care units experience distressing symptoms, particularly delirium [87]. Regardless of prognosis, it is a critical care component for all ICU patients [88]. Furthermore, ICU providers should have expertise in withholding or withdrawing unhelpful life-sustaining measures, including deactivating devices at the end of life [89, 90].

The review has identified key features surrounding patient and family-centredness in prognostication, communication and decision-making. Incorrect predictions and disagreements over patient prognoses can lead to significant moral distress for ICU staff, potentially hindering the care provided to patients and their families [76] and it is essential to convey a truthful and accurate prognosis to prevent harm and safeguard patients in the ICU [91]. The review supported the idea of timely, proactive, sensitive, and effective family-centred communication. It facilitated families' preparedness, support, and empowerment to make informed decisions. Discussing uncertainty and assessing family comprehension is crucial in achieving shared decision-making in clinician-family meetings regarding care goals for critically ill neurologic patients [92]. The use of vague or hedge language by ICU physicians, such as probabilistic statements, emotional expressions, metaphors, contingency statements, and unclear time references, often impeded effective communication [93]. Intensive care nurses felt undervalued in treatment decision-making processes, and their lack of involvement often led to frustration [94]. They believe their participation in decision-making would lead to more frequent collaboration with specialist palliative care teams [94]. Additionally, focusing solely on ICU interventions and physiology-centeredness may be perceived as incomplete [95]. It is also essential to find ways to communicate and understand the preferences of nonverbal and consciously mechanically intubated patients in the ICU to ensure their inclusion in the decision-making process [96]. The review findings recommend evaluating the provided care informally by gathering feedback from families or formally through survey questionnaires and qualitative interviews. The euroQ2 initiative assessed end-of-life care quality using the euro-QODD questionnaire in Danish and Dutch families [97]. The effective management of treatment limitations and the level of participation in the decision-making process were found to be the primary factors affecting family satisfaction with care [97]. Additionally, integrating palliative care into ICUs has been linked to improved emotional well-being, post-traumatic stress, and bereavement support [12].

The family-clinician Shared Decision-Making model in China increased family satisfaction, reduced patients’ ICU stay and optimally utilised ICU resources [98]. Several practices discussed in this review have described optimal resource utilisation as an outcome leading to equity. Anticipatory care planning often leads to decreased ICU admissions and reduced ICU length of stay [99]. Quality predictors like the absence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the last eight hours of life could be one of the indicators of ICU resource utilisation [100].

The current published guidelines and position statements on palliative and end of life care in ICUs [18,19,20,21,22,23,24] are developed as consensus-based approaches through Delphi studies and often underpinned by plain narrative reviews. This umbrella review has synthesised palliative care practices in ICUs, their outcomes, facilitators, and barriers from forty systematic reviews across the globe and might serve as a potential resource for future guidelines development.

Strengths and limitations

This review offers a comprehensive guide to the palliative and end-of-life practices in an intensive care setting. The findings are based on synthesising systematic and scoping reviews using rigorous and transparent methods by JBI guidelines [28]. The reporting adheres to PRIOR guidelines [101], but it should be noted that excluding non-English and grey literature, including policy documents, might be a limitation. The methodological challenges identified in some of the included reviews may have been transferred to this umbrella review during the synthesis process, potentially presenting a limitation. It should be noted that most scoping reviews included in this umbrella review did not assess the methodological quality of primary studies in their review. Furthermore, the limited representation of systematic reviews from low and middle-income countries may be a limitation, as the evidence synthesised in this review may not accurately represent international practice. As it is overview of reviews, there might be overlap of primary studies between reviews and findings may be amplified due to repetition.

Conclusion

ICU physicians must be skilled in prognostication and communication to enable families to make effective and timely decisions. Family communication should be scheduled proactively and early, emphasising open, effective, and culturally sensitive communication. This approach helps families to cope better with uncertainty, reduces distress, and shortens ICU stays. Before eliciting goals of care and making decisions, inter-team discussion and consensus building are essential. This approach aligns care with patient and family preferences, fosters collaboration, and reduces conflicts. Decision-making tools and aids can be helpful. Discussion and documentation of care preferences, especially resuscitation preferences, are vital practices that avoid unnecessary and inappropriate care at the end of life. Excellent end-of-life care must include symptom management, support for families, optimisation of hydration and nutrition, and withholding and withdrawing unhelpful treatment. Additionally, it should extend to care and support families immediately following death and during the bereavement period. Evaluating the quality of end-of-life care is essential and can be done informally through family feedback or a survey study. Evidence regarding practices related to palliative care provision in the ICU is more extensively developed than preparation for this care, which involves prognostication, communication, and decision-making. This umbrella review has comprehensively synthesised the current palliative care practices observed in ICUs, examining their impact on patient and family outcomes. It is a novel approach, contributes to existing knowledge and offers valuable insights for developing an appropriate care framework for critically ill patients facing end-of-life and their families.

Data availability

All available data for this review is already provided as supplementary files.

References

Hill SA, Dawood A, Boland E, Leahy HE, Murtagh FE (2022) Palliative medicine in the intensive care unit: needs, delivery, quality. BMJ Support Palliat Care 12(1):38–41

Ashana DC, Umscheid CA, Stephens-Shields AJ, Kohn R, Madden V, Harhay MO et al (2019) Determining the association between end-of-life care resources and patient outcomes in Pennsylvania ICUs. Crit Care Med 47(11):1591–1598

Braus N, Campbell TC, Kwekkeboom KL, Ferguson S, Harvey C, Krupp AE et al (2016) Prospective study of a proactive palliative care rounding intervention in a medical ICU. Intensive Care Med 42(1):54–62

Long AC, Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Nielsen EL, Back AL et al (2014) Quality of dying in the ICU: is it worse for patients admitted from the hospital ward compared to those admitted from the emergency department? Intensive Care Med 40(11):1688–1697

Penrod JD, Pronovost PJ, Livote EE, Puntillo KA, Walker AS, Wallenstein S et al (2012) Meeting standards of high-quality intensive care unit palliative care: clinical performance and predictors. Crit Care Med 40(4):1105–1112

Baldwin MR, Wunsch H, Reyfman PA, Narain WR, Blinderman CD, Schluger NW et al (2013) High burden of palliative needs among older intensive care unit survivors transferred to post-acute care facilities. Ann Am Thorac Soc 10(5):458–465

Creutzfeldt CJ, Engelberg RA, Healey L, Cheever CS, Becker KJ, Holloway RG et al (2015) Palliative care needs in the neuro-icu. Crit Care Med 43(8):1677–1684

Wang D, Ing C, Blinderman CD, Hua M (2019) Latent class analysis of specialized palliative care needs in adult intensive care units from a single academic medical center. J Pain Symptom Manage 57(1):73–78

Luethi N, Wermelinger SD, Haynes AG, Roumet M, Maessen M, Affolter B et al (2022) Development of an electronic poor outcome screening (ePOS) Score to identify critically ill patients with potential palliative care needs. J Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2022.154007

Adler K, Schlieper D, Kindgen-Milles D, Meier S, Schallenburger M, Sellmann T et al (2019) Will your patient benefit from palliative care? A multicenter exploratory survey about the acceptance of trigger factors for palliative care consultations among ICU physicians. Intensive Care Med 45(1):125–127

Park SY, Phua J, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Kang Y, Tada K et al (2018) End-of-life care in ICUs in East Asia: a comparison among China, Korea, and Japan. Crit Care Med 46(7):1114–1124

Cox CE, Gu J, Ashana DC, Pratt EH, Haines K, Ma J et al (2023) Trajectories of palliative care needs in the ICU and long-term psychological distress symptoms. Crit Care Med 51(1):13–24

Janczewski LM, Chandrasekaran A, Abahuje E, Ko B, Slocum JD, Tesorero K et al (2024) Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life care delivery in ICUs: a qualitative study. Crit Care Med 52(6):E289–E298

Michels G, Schallenburger M, Neukirchen M, John S, Janssens U et al (2023) Recommendations on palliative care aspects in intensive care medicine. Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04622-3

Tanaka Y, Masukawa K, Sakuramoto H, Kato A, Ishigami Y, Tatsuno J et al (2024) Development of quality indicators for palliative care in intensive care units and pilot testing them via electronic medical record review. J Intensive Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-023-00713-z

Shalman D (2024) Clinical outcomes of a joint ICU and palliative care multidisciplinary rounding model: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297288

Patarroyo-Aponte G, Shoar S, Ashley DM, Noorbaksh A, Patel D, Young A et al (2023) The role of palliative care consultation in withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment among ICU patients receiving veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO): a retrospective case-control study. Ame J Hospice Palliat Care 41:150–157

Mesukko J, Turale S, Jintrawet U, Niyomkar S (2020) Palliative care guidelines for physicians and nurses caring for children and their families in the pediatric intensive care units: a participatory action research study. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res 24(2):202–218

Mun E, Nakatsuka C, Umbarger L, Ruta R, McCarty T, Machado C et al (2017) Use of improving palliative care in the ICU (Intensive Care Unit) guidelines for a palliative care initiative in an ICU. Perm J. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-037

Luckett A (2017) End-of-life care guidelines and care plans in the intensive care unit. Br J Nurs 26(5):287–293

Yokota H (2016) The Guideline of the end-of-life care for the acute disease and intensive care by the JAAM, JSICM and JCS. Nihon rinsho Jpn J Clin Med 74(2):345–351

Bradley CT, Brasel KJ (2009) Developing guidelines that identify patients who would benefit from palliative care services in the surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 37(3):946–950

Mani RK, Bhatnagar S, Butola S, Gursahani R, Mehta D, Simha S et al (2024) Indian society of critical care medicine and Indian association of palliative care expert consensus and position statements for end-of-life and palliative care in the intensive care unit. Indian J Crit Care Med 28(3):200–250

Michels G, John S, Janssens U, Raake P, Schütt KA, Bauersachs J et al (2023) Palliative aspects in clinical acute and emergency medicine as well as intensive care medicine: consensus paper of the DGIIN, DGK, DGP, DGHO, DGfN, DGNI, DGG, DGAI, DGINA and DG Palliativmedizin. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 118(Suppl 1):14–38

Noome M, Dijkstra BM, van Leeuwen E, Vloet LCM (2017) Effectiveness of supporting intensive care units on implementing the guideline ‘End-of-life care in the intensive care unit, nursing care’: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 73(6):1339–1354

Kalies H, Schöttmer R, Simon ST, Voltz R, Crispin A, Bausewein C (2017) Critical attitudes and beliefs towards guidelines amongst palliative care professionals - results from a national survey. BMC Palliat Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0187-y

Belbasis L, Bellou V, Ioannidis JPA (2022) Conducting umbrella reviews. BMJ Med 1(1):e000071

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P (2014) Methodology for JBI umbrella reviews. In: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual: 2014 edition/Supplement . The Joanna Briggs Institute, Australia, pp 1–34

Salins N, Rao A, Dhyani VS, Prasad A, Mathew M, Damani A et al (2024) Palliative and end-of-life care practices for critically ill patients and their families in a peri-intensive care setting: a protocol for an umbrella review. Palliat Support Care. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951524000130

Ouzzani M, Hammady HM, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid AK (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PMM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA et al (2020) statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2020:10

Aromataris E, Fernandez RS, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P (2015) Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13:132–140

Nguyen D, Lightfoot D, Journeay WS (2023) Comorbidity and functional outcomes after hip fracture: an umbrella review protocol. JBI Evid Synth 21(5):1001–1008

Oczkowski S, Chung H, Hanvey L, Mbuagbaw L, You J (2016) Communication tools for end-of-life decision-making in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit CARE. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1264-y

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M et al (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Prod ESRC Methods Programme Version 1:b92

Mani R, Amin P, Chawla R, Divatia J, Kapadia F, Khilnani P et al (2012) Guidelines for end-of-life and palliative care in Indian intensive care units: ISCCM consensus ethical position statement. Indian J Crit Care Med 16(3):166

Myatra SN, Salins N, Iyer S, Macaden SC, Divatia JV, Muckaden M et al (2014) End-of-life care policy: an integrated care plan for the dying: a joint position statement of the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine (ISCCM) and the Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC). Indian J Crit Care Med 18(9):615–635

Saunders CH, Sierpe A, von Plessen C, Kennedy AM, Leviton LC, Bernstein SL et al (2023) Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-074256

Hoare S, Antunes BCP, Kelly M, Barclay SIG (2022) End-of-life care quality measures: beyond place of death. BMJ Support Palliat Care. https://doi.org/10.1136/spcare-2022-003841

Robertson-Preidler J, Biller-Andorno N, Johnson TJ (2017) What is appropriate care? An integrative review of emerging themes in the literature. BMC Health Serv Res 17(1):452

Aslakson R, Cheng J, Vollenweider D, Galusca D, Smith TJ, Pronovost PJ (2014) Evidence-based palliative care in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of interventions. J Palliat Med 17(2):219–235

Desanto-Madeya S, Safizadeh P (2017) Family satisfaction with end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of the literature. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 36(5):278–283

Leung D, Angus JE, Sinuff T, Bavly S, Rose L (2017) Transitions to end-of-life care for patients with chronic critical illness: a meta-synthesis. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 34(8):729–736

Roczen ML, White KR, Epstein EG (2016) Palliative care and intensive care units. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 18(3):201–211

Salins N, Deodhar J, Muckaden MA (2016) Intensive care unit death and factors influencing family satisfaction of intensive care unit care. Indian J Crit Care Med 20(2):97–103

Schram AW, Hougham GW, Meltzer DO, Ruhnke GW (2017) Palliative care in critical care settings: a systematic review of communication-based competencies essential for patient and family satisfaction. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 34(9):887–895

Spoljar D, Curkovic M, Gastmans C, Gordijn B, Vrkic D, Jozepovic A et al (2020) Ethical content of expert recommendations for end-of-life decision-making in intensive care units: a systematic review. J Crit Care 58:10–19

Bernal OA, Roberts B, Wu DS (2023) Interprofessional interventions to improve serious illness communication in the intensive care unit: a scoping review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 40(7):765–777

Coventry A, Gerdtz M, McInnes E, Dickson J, Hudson P (2023) Supporting families of patients who die in adult intensive care: a scoping review of interventions. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2023.103454

Effendy C, Yodang Y, Amalia S, Rochmawati E (2022) Barriers and facilitators in the provision of palliative care in adult intensive care units: a scoping review. Acute Crit Care 37:516–526

Green L, Stewart-Lord A, Baillie L (2022) End-of-life and immediate postdeath acute hospital interventions: scoping review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. https://doi.org/10.1136/spcare-2021-003511

Ivany E, Aitken L (2019) Challenges and facilitators in providing effective end of life care in intensive care units. Nurs Stand 34(6):44–50

Rao SR, Salins N, Joshi U, Patel J, Remawi BN, Simha S et al (2022) Palliative and end-of-life care in intensive care units in low- and middle-income countries: a systematically constructed scoping review. J Crit Care 71:154115

Ribeiro A, Pereira S, Nunes R, Hernández-Marrero P (2022) What do we know about experiencing end-of-life in burn intensive care units? A scoping review. Palliat Support Care. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951522001389

Yamamoto K, Hayama J, Yonekura Y, Nakayama K, Ota E (2022) A scoping review of advance care planning support for patients in intensive care units. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res 26(3):488–500

Hamdan Alshehri H, Olausson S, Öhlén J, Wolf A (2020) Factors influencing the integration of a palliative approach in intensive care units: a systematic mixed-methods review. BMC Palliat Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00616-y

Metaxa V, Anagnostou D, Vlachos S, Arulkumaran N, Sherihane B, van Dusseldorp I et al (2021) Palliative care interventions in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 47(12):1415–1425

Visser M, Houttekier D, Deschepper R, Deliens L (2014) Physician-related barriers for communication and patient and family centered decision making towards the end of life in the ICU: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 28(6):627–628

Araujo MCR, da Silva DA, Wilson AMMM (2023) Nursing interventions in palliative care in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Enferm Intensiva 34(3):156–172

Brooks LA, Bloomer MJ, Manias E (2019) Culturally sensitive communication at the end-of-life in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Aust Crit Care 32(6):516–523

Coventry A, Ford R, Rosenberg J, McInnes E (2020) A qualitative meta-synthesis investigating the experiences of the patient’s family when treatment is withdrawn in the intensive care unit. J Adv Nurs 76(9):2222–2234

Efstathiou N, Vanderspank-Wright B, Vandyk A, Al-Janabi M, Daham Z, Sarti A et al (2020) Terminal withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in adult intensive care units: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of perceptions, experiences and practices. Palliat Med 34(9):1140–1164

Hajizadeh N, Uhler LM, Herman SW, Lester JP (2016) Is shared decision making for end-of-life decisions associated with better outcomes as compared to other forms of decision making? A systematic literature review. MDM Policy Pract. https://doi.org/10.1177/2381468316642237

Hinkle LJ, Bosslet GT, Torke AM (2015) Factors associated with family satisfaction with end-of-life care in the ICU: a systematic review. Chest 147(1):82–93

Kerckhoffs MC, Kant M, van Delden JJM, Hooft L, Kesecioglu J, van Dijk D (2019) Selecting and evaluating decision-making strategies in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. J Crit Care 51:39–45

Khandelwal N, Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Coe NB, Long AC, Curtis JR (2015) Estimating the effect of palliative care interventions and advance care planning on ICU utilization: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 43(5):1102–1111

Pignatiello G, Hickman RLJ, Hetland B, Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M, Aslakson R, Cheng J, Vollenweider D, Galusca D, Smith TJ, Pronovost PJ, Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Jourdain M, Bornstain C, Wernet A, Le Gall J-R, Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Schlemmer B, Braun UK, Beyth RJ, Ford ME, McCullough LB, Burns JP, Mello MM, Studdert DM, Puopolo AL, Truog RD, Brennan TA, Campbell ML, Guzman JA, Carson SS, Carson SS, Bach PB, Char SJL, Evans LR, Malvar GL, White DB, Collins L, Murphy S, Strecher V, Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, Fulkerson WJ, Goldman L, Knaus WA, Oye RK, Cox CE, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, Hough CL, Kahn JM, White DB, Carson SS, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Bensink ME, Ramsey SD, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, O’Toole E, Gordon NH, Hejal R, Peerless J, Hickman R, Dolan RJ, Dowdy MD, Robertson C, Bander JA, Dowling J, Wang B, Evans J, Stanovich KE, Girard TD, Glanz K, Bishop DB, Hatler CW, Grove C, Strickland S, Barron S, White BD, Heatherton TF, Hickman RL, Daly BJ, Lee E, Hickman RL, Douglas SL, Higgins JPT, Green S, Jacob BM, Institute of Medicine, Horton C, Rance-ashley S, Field T, Patterson R, Johnson C, Frobos C, Kahn JM, Le T, Angus DC, Cox CE, Hough CL, White DB, Kaufer M, Murphy P, Barker K, Mosenthal A, Kodali S, Stametz R, Clarke D, Bengier A, Sun H, Layon AJ, Darer J, Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Harris Smith J, Mosenthal AC, Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, Azoulay E, Lerner J, Li Y, Piercarlo V, Kassam K, Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, Haley KJ, Massaro AF, Wallace RF, Cody S, McAdam JL, Fontaine DK, White DB, Dracup KA, Puntillo KA, McCannon JB, O’Donnell WJ, Thompson BT, El-Jawahri A, Chang Y, Ananian L, Volandes AE, Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, Lavery R, Retano A, Livingston DH, Murray MA, Miller T, Fiset V, O’Connor A, Jacobsen MJ, Myburgh J, Abillama F, Chiumello D, Dobb G, Jacobe S, Kleinpell R, Dunstan GR, National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, National Institute of Nursing Research, Nelson J, Bassett R, Boss R, Brasel K, Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, Lustbader DR, Mosenthal AC, Mulkerin C, Nelson JE, Kinjo K, Meier DE, Ahmad K, Morrison RS, Nelson JE, Tandon N, Mercado AF, Camhi SL, Ely EW, Morrison RS, Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE, O’Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, Elmslie T, Jolly E, Hollingworth G, Drake E, Obringer K, Hilgenberg C, Booker K, Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Ely EW, Petrinec AB, Mazanec PM, Burant CJ, Hoffer A, Daly BJ, Scheunemann L, McDevitt M, Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, Dugan DO, Blustein J, Cranford R, Young EWD, Schulz R, Sherwood P, Shelton W, Moore CD, Socaris S, Gao J, Dowling J, Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM, Starcke K, Brand M, Tillyard ARJ, Vig EK, Taylor JS, Starks H, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K, Weldring T, Smith SMS, Wendler D, Rid A, White DB, Wiencek C, Winkelman C, Wilson ME, Krupa A, Hinds RF (2018) End-of-life decision support in the ICU: where are we now? Western J Nurs Res 40(1):84–120

Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, Carson SS, Hanson LC (2011) Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: a systematic review. Chest 139(3):543–554

Song K, Amatya B, Voutier C, Khan F (2016) Advance care planning in patients with primary malignant brain tumors: a systematic review. Front Oncol 6:226199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2016.00223. Accessed 30 Jul 2024

Wilson ME, Mittal A, Karki B, Dobler CC, Wahab A, Curtis JR et al (2020) Do-not-intubate orders in patients with acute respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 46(1):36–45

Durán-Crane A, Laserna A, López-Olivo MA, Cuenca JA, Díaz DP, Cardenas YR et al (2019) Clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements about pain management in critically ill end-of-life patients: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 47(11):1619–1626

Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA (2011) Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 39(5):1174–1189

Mazzu M, Campbell ML, Schwartzstein RM, White DB, Mitchell SL, Fehnel CR (2023) Evidence guiding withdrawal of mechanical ventilation at the end of life: a review: running title: withdrawal of mechanical ventilation. J Pain Symptom Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2023.05.009

McPherson K, Carlos WG, Emmett TW, Slaven JE, Torke AM (2019) Limitation of life-sustaining care in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med 14(5):303–310

Alyami HM, Chan RJ, New K (2019) End-of-life care preferences for people with advanced cancer and their families in intensive care units: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 27(9):3233–3244

McAndrew NS, Leske JS, Garcia A (2011) Influence of moral distress on the professional practice environment during prognostic conflict in critical care. J Trauma Nurs: Off J Soc Trauma Nurses 18(4):221–230

Brekelmans A, Ramnarain D, Pouwels S (2022) Bereavement support programs in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 64(3):E149–E157

Galazzi A, Adamini I, Bazzano G, Cancelli L, Fridh I, Laquintana D et al (2022) Intensive care unit diaries to help bereaved family members in their grieving process: a systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103121

Velarde-García J, Pulido-Mendoza R, Moro-Tejedor M, Cachón-Pérez J, Palacios-Ceña D (2016) Nursing and end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 18(2):115–123

Yu Y, Xiao L, Chamberlain DJ (2021) Perceptions of care in patients from culturally and linguistically diverse background during acute and critical illness: a integrative literature review. Aust Crit Care 34(5):486–495

MacIel CB, Barden MM, Youn TS, Dhakar MB, Greer DM (2020) Neuroprognostication practices in postcardiac arrest patients: an international survey of critical care providers. Crit Care Med 48(2):E107–E114

Haniffa R, Isaam I, De Silva AP, Dondorp AM, Keizer NF (2018) Performance of critical care prognostic scoring systems in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-017-1930-8

Drury A, Muscat DM, Wibrow B, Jacques A, Anstey M (2022) Integrating the choosing wisely 5 questions into family meetings in the intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial investigating the effect on family perceived involvement in decision-making. J Patient Exp. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735221092623

Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, Danis M, White DB (2016) Shared decision making in ICUs: an American college of critical care medicine and American thoracic society policy statement. Crit Care Med 44(1):188–201

Vemuri S, Hynson J, Williams K, O’Neill J, Gillam L (2023) Shepherding parents to prepare for end-of-life decision-making: a critical phenomenological study of the communication approach of paediatricians caring for children with life-limiting conditions in Australia. BMJ Open 13(12):e075740

Dos Santos DCL, Da Silva MM, Moreira MC, Zepeda KGM, Gaspar RB (2017) Care planning for patients receiving palliative care in an oncology intensive care unit. ACTA Paulista de Enfermagem 30(3):295–300

Puntillo KA, Arai S, Cohen NH, Gropper MA, Neuhaus J, Paul SM et al (2010) Symptoms experienced by intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying. Crit Care Med 38(11):2155–2160

Puntillo K, Nelson JE, Weissman D, Curtis R, Weiss S, Frontera J et al (2014) Palliative care in the ICU: relief of pain, dyspnea, and thirst - a report from the IPAL-ICU advisory board. Intensive Care Med 40(2):235–248

Obarzanek L, Campbell ML (2021) Withholding and withdrawal of life support in critically ill patients at the end of life: pain is not the only symptom to manage. Intensive Care Med 47(4):489–490

Rady MY, Verheijde JL (2014) End-of-life care and deactivation of left ventricular assist devices. Crit Care Med 42(7):e534

Robichaux CM, Clark AP (2006) Practice of expert critical care nurses in situations of prognostic conflict at the end of life. Am J Crit Care 15(5):480–491

Fleming V, Prasad A, Ge C, Crawford S, Meraj S, Hough CL et al (2023) Prevalence and predictors of shared decision-making in goals-of-care clinician-family meetings for critically ill neurologic patients: a multi-center mixed-methods study. Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04693-2

Mittal V, Hakes NA, Magnus D, Batten JN (2023) Vagueness in goals-of-care conferences for critically ill patients: types of hedge language used by physicians. Crit Care Med 51(11):1538–1546

Schallenburger M, Schwartz J, Icks A, In der Schmitten J, Batzler YN, Meier S et al (2024) Triggers of intensive care patients with palliative care needs from nurses’ perspective: a mixed methods study. Crit Care 28(1):181

Kruser JM, Benjamin BT, Gordon EJ, Michelson KN, Wunderink RG, Holl JL et al (2019) Patient and family engagement during treatment decisions in an ICU: a discourse analysis of the electronic health record. Crit Care Med 47(6):784–791

ten Hoorn S, Elbers PW, Girbes AR, Tuinman PR (2016) Communicating with conscious and mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1483-2

Gerritsen RT, Jensen HI, Koopmans M, Curtis JR, Downey L, Hofhuis JGM et al (2018) Quality of dying and death in the ICU. The euroQ2 project. J Crit Care 44:376–382

Liu X, Humphris G, Luo A, Yang M, Yan J, Huang S et al (2022) Family-clinician shared decision making in intensive care units: cluster randomized trial in China. Patient Educ Couns 105(6):1532–1538

Hartog CS, Maia PA, Ricou B, Danbury C, Galarza L, Schefold JC et al (2022) Changes in communication of end-of-life decisions in European ICUs from 1999 to 2016 (Ethicus-2) - a prospective observational study. J Crit Care 68:83–88

Hodde NM, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Steinberg KP, Curtis JR (2004) Factors associated with nurse assessment of the quality of dying and death in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 32(8):1648–1653

Gates M, Gates A, Pieper D, Fernandes RM, Tricco AC, Moher D et al (2022) Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: development of the PRIOR statement. BMJ 378:e070849

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. The study is funded by The End of Life Care in India Taskforce (ELICIT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS: Guarantor of the overview, Conceptualisation, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, and funding acquisition. VSD: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—review & editing. MM: Data curation, formal analysis, writing—review & editing. AP: Data curation, formal analysis, writing—review & editing. AR: Conceptualisation and writing—review & editing, Corresponding author. AD: Writing—review & editing. KR: Writing—review & editing. SN: Writing—review & editing. VS: Writing—review & editing. SR: Writing—review & editing. Shivakumar Iyer: Writing—review & editing. RG: Writing—review & editing. RKM: Writing—review & editing. SB: Writing—review & editing. SS: Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The Authors declare no competing interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salins, N., Dhyani, V.S., Mathew, M. et al. Assessing palliative care practices in intensive care units and interpreting them using the lens of appropriate care concepts. An umbrella review. Intensive Care Med 50, 1438–1458 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-024-07565-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-024-07565-7