Abstract

Adolescents hearing non-existent voices may be at risk for psychosis, but the prevalence of voice-hearing (VH) in the general population complicates clinical interpretations. Differentiating between VH with and without distress may aid treatment decisions in psychosis services, but understanding the differences between these two phenomena as they present in the normal adolescent population is necessary to validate this differentiation. The present study compared VH with and without distress in 10,346 adolescents in relation to clinical characteristics, known risk factors, predictors and psychosocial moderators of psychosis. A population-based cohort of Norwegian 16–19 years old adolescents completed a comprehensive web-based questionnaire, including two questions from the extended Launay-Slade Hallucinations Scale: (1) I often hear a voice speaking my thoughts aloud and (2) I have been troubled by hearing voices in my head. Adolescents reporting no VH, non-distressing VH or distressing VH were compared on 14 psychosocial and clinical variables. A multinomial regression model showed that non-disturbing voices were predicted by better school grades, social dysfunction, distractibility, affective symptoms and experience of trauma, while the disturbing voices were predicted by the experience of bullying and trauma, perceived negative self-worth and self-efficacy, less family support, dysregulation of activation, distractibility, self-harm and anxiety. Hearing voices without distress versus being distressed by the voices is related to different constellations of psychosocial variables, suggesting that they represent two separate groups of adolescents. The findings validate the emphasis on distress in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hearing non-existent voices is a potential marker of psychosis development, and may create subjective distress and anxiety with corresponding functional decline and mental health problems. However, voice-hearing (VH) is quite common in the age period when psychosis develops, complicating clinical interpretation [1]. The prevalence of VH and auditory hallucinations (AVH) in the general population has been estimated to be around 4–7.5% [2,3,4,5]. Importantly, there seems to be a developmental effect, with psychotic symptoms (predominantly AVH) occurring in 17% of children aged 9–12 but only in 7.5% of adolescents aged 13–18 years [6]. A previous study from the present dataset found that 10.6% of a population-based sample of 9646 adolescents reported often hearing a voice speaking thoughts out loud [7]. However, only 5.3% reported that they experienced being troubled by voices, suggesting two groups of VH adolescents; a relatively large group hearing voices without feeling distressed, and a smaller group being distressed by the voices.

Both these groups may be referred to early psychosis intervention services, but the existence of distress may guide further treatment decisions [8], since distress may predict transition to psychosis [9]. Distress during VH, related to the existence of a non-realistic, psychotic interpretation of the voices that consequently increases anxiety, vigilance and personal suffering, is of clinical importance. VH may be considered to be several different phenomena: a symptom of psychosis [10], a symptom of psychosis risk; often depicted as “high-risk” (HR) “ultra-high risk”, “prodromal state” and “at-risk mental state” for psychosis, as well as a “psychosis-(like) experience” (PLE/PE), or as a normal phenomenon [8, 11,12,13]. Not being distressed suggests a non-psychotic interpretation; e.g. “I am hearing voices because I am tired” or “Sometimes my mind plays tricks on me” (for details, see [14, 15]). However, one may question the emphasis on distress, as there is limited knowledge on whether non-distressed voice-hearers are different to voice-hearers who are distressed by their voices. Do these groups differ in psychosocial characteristics known to be related to the development of psychosis? Research on adults demonstrates that there is a considerable high number of voice-hearers in the population who do not need psychiatric care [16, 17]. By examining characteristics of different voice-hearers in early development, more light could be shed on the possible symptom trajectories of voice-hearing individuals. If the non-distressing VH experience is a variation of normal perceptual phenomena, while the distressed adolescents are on a (non-deterministic) pathway to psychosis, the latter group should possibly have more psychosis-related characteristics, typically; (1) comorbid mental health symptoms (2) risk factors for psychosis (3) predictors of psychosis conversion, and (4) fewer psychosocial moderators and resilience factors.

Several mental health conditions often co-exist with psychosis. The most prevalent are affective symptoms [18], anxiety [19] and illicit substance abuse [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. General markers of sub-optimal mental health are typically present before psychosis onset, such as anxiety and depressive disorders [11] and dysregulated activation [27]. Self-harm is particularly prevalent in early untreated psychosis phases [28], and is an important marker of mental distress in adolescents. Psychosocial variables may alone or in interaction with other variables or genetic vulnerability heighten the risk for psychosis [29], e.g. illicit substance use [30]. Cannabis has been implicated in psychosis development in prospective studies [31, 32], especially for moderate to severe use and/or if started in the early teens [33,34,35]. Similarly, other substances acting on dopamine receptors have been linked to psychosis development, especially (meta)amphetamines [36]. There is also an increasing international consensus that childhood trauma is a risk factor for psychosis [37,38,39,40,41] and for PEs [42], with reports of an almost three–fold greater likelihood of experiencing psychotic symptoms after childhood trauma [43], with a dose–response relationship [39, 40, 43,44,45,46]. A dose–response relationship of a history of bullying and psychotic experiences has also been reported [47].

Predictors of conversion to psychosis include attenuated positive symptoms and functional decline in areas of school and social functioning. General and social functioning has been shown to be significantly lower for child and adolescent patients with psychotic-like experiences than without [48, 49]. Negative symptoms and social withdrawal [50] predict psychosis, typically seen as reduced school attendance in youngsters. In a five year prospective study conversion to psychosis was best predicted by disorganized communication, suspiciousness, verbal memory deficits, and decline in social functioning [51]. Furthermore, cognitive deficits [52, 53] and being part of high-risk populations [54, 55] are shown to be predictive of psychosis conversion [56,57,58]. For adolescents, cognitive difficulties are typically reflected by lower school grades.

Finally, there may be moderators of psychosis risk related to psychological resilience; family support, self-efficacy and experience of self-worth. Smith and colleagues [59] found that lower self-esteem was related to severity and negative content of AVH, and negative self-evaluations have been shown to be strongly related to psychosis even when depression has been controlled for [60, 61]. Reduced self-efficacy—an individual's belief in his or her capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments [62]—has been shown also in patients at-risk for psychosis [63]. Family support is important for avoiding new episodes of psychosis, [60, 64, 65], but is decreased and related to symptomatic and functional improvement in HR patients as well [49, 66].

By including information regarding the risk factors and characteristics described above, the present study aims to test the validity of a distress-based distinction of the concept of VH. We expect to find a more psychosis-associated psychosocial profile among the distressed adolescents compared to the voice-hearers not distressed by the voices; more comorbid mental health symptoms (anxiety, affective symptoms, dysregulation of activation, self-harm), risk factors for psychosis (experience of trauma, bullying, illicit drug use) and predictors of psychosis conversion and markers of mental distress (social functioning, school grades, days absent from school, distractibility) and fewer psychosocial moderators and resilience factors (family support, self-efficacy, experience of self-worth).

Methods

Sample

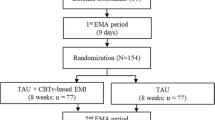

The present study included a population-based sample of adolescents participating in the fourth wave of the Bergen Child study (see https://uni.no/en/uni-health/rkbu-vest/the-bergen-child-study/ for details), headed by the Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health and Child Welfare, Norce Norwegian Research Center. The sample included all adolescents attending high school during the spring 2012, mostly students born between 1993 and 1995. The adolescents received information about the study to their homes and/or via their school e-mail, and completed the internet-based questionnaire at school upon consent. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Western Norway. The current study is based on the first version of quality-assured data files released in May 2012. Information about sex and year of birth were based on the personal identity number in the Norwegian National Population Register. Of the included adolescents (n = 19,121), 11,092 completed or filled in parts of the questionnaire. Some subjects (n = 746) were removed due to missing personal identity numbers and unreliable answer profiles resulting in a total sample of 10,346 adolescents in the present study. The sample has previously been found to be representative of Norwegian high school youth [67].

Assessment

Voice-hearing

Presence of VH was assessed with two items from extended Launay-Slade Hallucinations Scale (LSHS-E) [68]; (1) “I often hear a voice speaking my thoughts aloud”; and (2) “I have been troubled by hearing voices in my head”. Responses are given on a 5-point scale (0 = “certainly does not apply to me”, 1 = “possibly does not apply to me”, 2 = “unsure”, 3 = “possibly applies to me” and 4 = “certainly applies to me”). Factor analyzes of the LSHS-E have shown that both of these items load on an underlying “auditory hallucinations” factor [68, 69], but in addition, item 2 load on a factor associated with psychopathology [70, 71], and has been associated with higher degree of negative emotionality than item 1 [72]. The five response categories to the two VH items were recoded to responses “0″ and “1″ being coded as “No endorsement” (0) and responses “3″ and “4″ being coded as endorsement (1). Adolescents answering “2″ were coded as unsure and were excluded from the group analysis (n = 473). The following three groups were examined (1) No VH (no endorsement, both items) (2) VH (endorsement of hearing voices only) and (3) Distressing VH (endorsement of distressing voices). This procedure resulted in a score in one of these three response categories only, thus the subjects were only allocated to one of the three groups.

Predictor variables

The predictor variables were based on selected items about psychosocial, demographic and clinical status and characteristics chosen from the web-based questionnaire based on previous studies on factors related to early psychosis, see Table 1 for details. To validate the constructs and content, seven of the predictor variables were derived using confirmatory factor analyzes (factor loadings not given, goodness of fit: χ2 = 17,665.639, p < 0.001, CFI =0.92, TLI =0.91, RMSEA =0.048, 90% RMSEA CI 0.047–0.049, RMSEA close fit =1.000). For the other seven predictor variables factor analysis was not required since the relevant questions were clearly defined with narrow connotations. Six of these variables were based on one single item and one was based on 4 items. The non-factor analyses variables were; (1) Experience of trauma; 4 items about negative life events from a previous Norwegian national survey [73] (2) Experience of bullying; from the national Olweus bullying survey [74] (3) Illicit drug use; developed for the web-based questionnaire [75] (4) Self-harm; from the Child and Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study [76] (5) Anxiety; from the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders; SCARED [77] (6) School grades; mean grades from official registers from the Hordaland County, excluding Physical Education, and (7) Days absent from school (web-based questionnaire).

The factor analyses-based variables were (1) Family support; nine items from the Resilience Scale for Adolescents; READ [78]; (2) Self-efficacy; three items from READ (3) Distractibility, four items from the adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; ASRS [79], two items from The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SDQ [80] and one item from the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; SMFQ [81]; (4) Dysregulation of activation; three items from ASRS, two items from SDQ and one items from SMFQ (5) Experience of self-worth; seven items from SMFQ (6) Affective symptoms; seven items from SMFQ, and (7) Social functioning; three items from the Autism symptom self-report; ASSERT [82] and two items from READ.

Statistics

IBM SPSS Statistics 23 was used for descriptive analyses [83]: mean, standard deviation (SD) and skewness. Factor scores were estimated through confirmatory factor analysis with the program Mplus 7.4 [84]. Since the outcome variable was nominal with three categories, a multinomial regression model was analyzed with SPSS. All predictors were included simultaneously in one block [85], and give adjusted estimates for all predictor variables. Thus, this model analyzes the effect of “hearing voices” and “being troubled by voice hearing” in contrast to no voice hearing as the reference category.

Results

Descriptive results

Of the 10,346 adolescents, 53.5% were girls. The mean age was 17.70 years (SD =1.60). The prevalence of VH was No VH = 80.6% (N = 7954), VH =13.9% (N = 1371), and Distressing VH = 5.6% (N = 548), yielding a total of n = 9873 (excluding adolescents answering “unsure”). The descriptive results for the predictor variables are presented in Table 2 and 3. The results indicate relatively low prevalence of endorsement in general, except for Anxiety with 15% endorsement.

Prediction of voice-hearing

The results from the predictor model of VH are presented in Table 4. The outcome variable was specified with the predictor effect on “VH” and “distressing VH” against the “No VH” as the reference category. Models for subjects between 16–19 and 16–25 years old are presented. No evidence for high multicollinearity between the predictor variables emerged, indicated by VIF with the highest value of 4.75. One predictor correlation was found to be high (r = 0.86), with 73% explained common variance.

Some variables were related to the category “VH” in contrast to “no VH”. These were Experience of trauma, School grades, Distractibility, Social dysfunction, Affective symptoms, Gender, and Age. Including a broader age span resulted in almost identical estimates as the model based on subjects 16–19 years old. This means that not distressing VH was more plausible among subjects with trauma experiences, higher mean academic characters, more problems regarding distractibility and social functioning, higher levels of affective symptoms, younger age and among boys in contrast to girls. The strongest statistical relation was Social dysfunction with odds ratio (OR) at 2.21, which means 121% increased risk for VH for each increase in this variable.

Regarding distressing VH, the following predictors were found to be statistically significant: experience of bullying, trauma exposure, negative self-worth, less family support, stronger levels of distractibility, dysregulation of activation, negative self-efficacy, self-harm, anxiety, and lower age. The strongest risk factor was found to be negative self-worth.

Conclusion

Hearing thoughts out aloud without being disturbed by them versus being distressed by VH was mainly predicted by different constellations of psychosocial characteristics, suggesting that VH with and without distress represent two different groups of adolescents. Overall, this supports the emphasis put on distress in clinical practice. Not being disturbed by the voices was primarily related to social dysfunction, in addition to the experience of trauma, distractibility, affective symptoms, higher school grades, male gender and older age. Perceiving the voices as disturbing was related to the experience of bullying and trauma, negative self-worth, and self-efficacy, less family support, dysregulation of activation, distractibility, self-harm, anxiety and younger age. Negative self-worth was the strongest predictor.

As expected, the adolescents with disturbing VH were characterized by most of the typically depicted comorbid mental health symptoms in psychosis (anxiety, dysregulation of activation, self-harm), risk factors for psychosis (experience of trauma and bullying), predictors of psychosis conversion and markers of mental distress (distractibility) and fewer psychosocial moderators and resilience factors (family support, self-efficacy, experience of self-worth). Some psychosis-related psychosocial variables were not, however, related to distressing voices in this population-based sample, i.e. worse school grades, more school absence, reduced social functioning, illicit substance use and more affective symptoms. This may be explained by characteristics of the sample, as most attended high school. Adolescents with major issues related to these variables may not be part of the present sample because they probably have dropped out of school.

Adolescents not distressed by voices displayed a somewhat different profile of psychosocial characteristics as compared to their no VH peers. Social dysfunction was the strongest predictor, followed by better grades and male gender. Distractibility was related to voice-hearing in both groups, and this is consistent with several studies finding reduced attentional control in all voice hearers regardless of diagnosis and treatment needs [86]. In addition, the importance of experience of trauma was seen for both groups, in line with studies showing childhood trauma in broader groups than psychosis only [41]. The effect of lower age yielding more VH seen in previous studies [6] was also seen in both groups. The relationship to better grades for the not distressed by voices group seems paradoxical. It can be speculated that this may reflect high-or over-achieving youngsters with suboptimal healthy work-rest balance, social life and mental overload. Youngsters within a high-functioning autism/Asperger spectrum continuum with low social functioning, male gender, better grades and voice hearing could also belong in this group. Increased school related stress and a more competitive school environment have been suggested as factors for explaining increases in student mental health problems in Norway, supporting the first speculation, and in line with a somewhat increased affective symptom load.

The difference between the distressed and non-distressed group seems to be related to negative self-apprehensions, less support from family and possibly peers via bullying, all together potentially leading to reduced ability to use psychological and social coping strategies. Dysregulation of activation including questions on restlessness, anxiety and self-harm creates a picture of youngsters in emotional distress. The relationship between these variables and the development of psychosis should be studied in more detail. The present study does not test causality; whether these characteristics are an effect of the troubling voices or vice versa. The topic clearly awaits longitudinal studies.

Other questions also remain unanswered, representing limitations of the present study. We do not know whether being distressed or disturbed by the voices actually is a sign of a HR or a psychotic state, which is dependent on a more comprehensive understanding of the individual interpretations of the voices than is possible via a web-based questionnaire. For instance, there may be a few individuals within the autism-spectrum in the present sample (0.45% broader defined Autism Spectrum Disorders; [82]) who may have very concrete interpretations of “voice speaking my thoughts aloud”, but since these youngsters also have a vulnerability for psychosis exclusion would create a biased sample. The current paradigm was not set out to test whether the voice hearing was part of other mental health disorders with frequent voice hearing. Some of the risk factors reported in the present study clearly overlap with other disorder, such as borderline and dissociative disorders. We do not know what the phenomenon of hearing voices out loud actually stands for, and we do not have data on the frequency or content of these experiences, variables which have been shown to identify voice-hearers in treatment [16]. When adolescents actually seek help for their voices, they present with a high level of suffering, a reduced level of functioning and severe and/or comorbid psychopathology [87].

There is a trade-off between the comprehensiveness of topics covered by the web-based questionnaire, the sample size and the in-depth understanding of the different phenomena in question. Finally, the study did not test the relative importance of the selected features in explaining the hearing voices categories, and whether the distress-related distinction is categorical or continuous. The strengths of the present study are the high number of participants and the representativeness of the sample via the population-based inclusion [67], supported by the high rate (93%) of 16–18 year olds that attend high-school in Norway [88]. In addition, the sample size enables the possibility of examining several important variables simultaneously with high levels of statistical power.

In conclusion, the findings support the validity of the clinical distinction between adolescents being disturbed by VH or not as seen in high quality early intervention services. Since VH in itself is a relatively frequent experience in adolescence, examining the amount of personal distress related to these alternative perceptual experiences may aid referral practices and treatment decisions in services for psychosis or high risk for psychosis.

References

Demmin DL, DeVylder JE, Hilimire MR (2017) Screening for sub-threshold psychotic experiences and perceived need for psychological services. Early Interv Psychiatry 11(2):139–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12222

Krakvik B, Laroi F, Kalhovde AM, Hugdahl K, Kompus K, Salvesen O, Stiles TC, Vedul-Kjelsas E (2015) Prevalence of auditory verbal hallucinations in a general population: a group comparison study. Scand J Psychol 56(5):508–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12236

Linscott RJ, van Os J (2013) An updated and conservative systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: on the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychol Med 43(6):1133–1149. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001626

Van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L (2009) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med 39(2):179

McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Chiu WT, de Jonge P, Fayyad J, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Kovess-Masfety V, Lepine JP, Lim CC, Mora ME, Navarro-Mateu F, Ochoa S, Sampson N, Scott K, Viana MC, Kessler RC (2015) Psychotic Experiences in the general population: a cross-national analysis based on 31,261 respondents from 18 countries. JAMA Psychiatry 72(7):697–705. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0575

Kelleher I, Connor D, Clarke MC, Devlin N, Harley M, Cannon M (2012) Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Psychol Med 42(09):1857–1863

Kompus K, Løberg EM, Posserud MB, Lundervold AJ (2015) Prevalence of auditory hallucinations in Norwegian adolescents: results from a population-based study. Scand J Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12219

Kline E, Thompson E, Bussell K, Pitts SC, Reeves G, Schiffman J (2014) Psychosis-like experiences and distress among adolescents using mental health services. Schizophr Res 152(2):498–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.012

Rapado-Castro M, McGorry PD, Yung A, Calvo A, Nelson B (2014) Sources of clinical distress in young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res 165(1):15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.03.022

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13(2):261–276

Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, Addington J, Riecher-Rossler A, Schultze-Lutter F, Keshavan M, Wood S, Ruhrmann S, Seidman LJ, Valmaggia L, Cannon T, Velthorst E, De Haan L, Cornblatt B, Bonoldi I, Birchwood M, McGlashan T, Carpenter W, McGorry P, Klosterkotter J, McGuire P, Yung A (2013) The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry 70(1):107–120. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.269

Nieman DH, McGorry PD (2015) Detection and treatment of at-risk mental state for developing a first psychosis: making up the balance. Lancet Psychiatry 2(9):825–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00221-7

McGorry PD (2015) Early intervention in psychosis: obvious, effective, overdue. J Nerv Ment Dis 203(5):310–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000284

Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell'Olio M, Francey SM, Cosgrave EM, Killackey E, Stanford C, Godfrey K, Buckby J (2005) Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 39(11–12):964–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x

Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Somjee L, Markovich PJ, Stein K, Woods SW (2002) Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured interview for prodromal syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry 159(5):863–865

Baumeister D, Sedgwick O, Howes O, Peters E (2017) Auditory verbal hallucinations and continuum models of psychosis: A Systematic review of the healthy voice-hearer literature. Clin Psychol Rev 51:125–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.010

Johns LC, Kompus K, Connell M, Humpston C, Lincoln TM, Longden E, Preti A, Alderson-Day B, Badcock JC, Cella M, Fernyhough C, McCarthy-Jones S, Peters E, Raballo A, Scott J, Siddi S, Sommer IE, Larøi F (2014) Auditory Verbal hallucinations in persons with and without a need for care. Schizophrenia Bull 40(4):S255–S264. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu005

Upthegrove R, Marwaha S, Birchwood M (2016) Depression and Schizophrenia: cause, consequence or trans-diagnostic issue? Schizophr Bull. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw097

Achim AM, Maziade M, Raymond E, Olivier D, Merette C, Roy MA (2011) How prevalent are anxiety disorders in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis and critical review on a significant association. Schizophr Bull 37(4):811–821. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp148

Margolese HC, Malchy L, Negrete JC, Tempier R, Gill K (2004) Drug and alcohol use among patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses: levels and consequences. Schizophr Res 67(2–3):157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00523-6

Kovasznay B, Fleischer J, Tanenberg-Karant M, Jandorf L, Miller AD, Bromet E (1997) Substance use disorder and the early course of illness in schizophrenia and affective psychosis. Schizophr Bull 23(2):195–201

Hartz SM, Pato CN, Medeiros H, Cavazos-Rehg P, Sobell JL, Knowles JA, Bierut LJ (2014) Comorbidity of severe psychotic disorders with measures of substance use. JAMA Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3726

Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IR, Gagnon E, Guyer M, Howes MJ, Kendler KS, Shi L, Walters E, Wu EQ (2005) The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol Psychiatry 58(8):668–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034

Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Byerly MJ, Glick ID, Canive JM, McGee MF, Simpson GM, Stevens MC, Lieberman JA (2003) The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophr Bull 29(1):15–31

Cantor-Graae E, Nordstrom LG, McNeil TF (2001) Substance abuse in schizophrenia: a review of the literature and a study of correlates in Sweden. Schizophr Res 48(1):69–82

Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK (1990) Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse Results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. J Am Med Assoc 264(19):2511–2518

Skjelstad DV, Malt UF, Holte A (2010) Symptoms and signs of the initial prodrome of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 126(1–2):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.003

Mork E, Walby FA, Harkavy-Friedman JM, Barrett EA, Steen NE, Lorentzen S, Andreassen OA, Melle I, Mehlum L (2013) Clinical characteristics in schizophrenia patients with or without suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm–a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 13:255. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-255

van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BP (2010) The environment and schizophrenia. Nature 468(7321):203–212. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09563

Løberg EM, Helle S, Nygård M, Berle JO, Kroken RA, Johnsen E (2014) The cannabis pathway to non-affective psychosis may reflect less neurobiological vulnerability. Front Psychiatry 5:159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00159

Andreasson S, Allebeck P, Engstrom A, Rydberg U (1987) Cannabis and schizophrenia. A longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Lancet 2(8574):1483–1486

Zammit S, Allebeck P, Andreasson S, Lundberg I, Lewis G (2002) Self reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort study. BMJ 325(7374):1199

Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, McClay J, Murray R, Harrington H, Taylor A, Arseneault L, Williams B, Braithwaite A, Poulton R, Craig IW (2005) Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction. Biol Psychiatry 57(10):1117–1127

Konings M, Henquet C, Maharajh HD, Hutchinson G, Van Os J (2008) Early exposure to cannabis and risk for psychosis in young adolescents in Trinidad. Acta Psychiatr Scand 118(3):209–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01202.x

Di Forti M, Sallis H, Allegri F, Trotta A, Ferraro L, Stilo SA, Marconi A, La Cascia C, Reis Marques T, Pariante C, Dazzan P, Mondelli V, Paparelli A, Kolliakou A, Prata D, Gaughran F, David AS, Morgan C, Stahl D, Khondoker M, Maccabe JH, Murray RM (2014) Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt181

Bramness JG, Gundersen OH, Guterstam J, Rognli EB, Konstenius M, Loberg EM, Medhus S, Tanum L, Franck J (2012) Amphetamine-induced psychosis–a separate diagnostic entity or primary psychosis triggered in the vulnerable? BMC Psychiatry 12:221. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-221

Larkin W, Read J (2008) Childhood trauma and psychosis: Evidence, pathways, and implications. J Postgrad Med 54(4):287–293

Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, Read J, van Os J, Bentall RP (2012) Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bull 38(4):661–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/Schbul/Sbs050

van Nierop M, Lataster T, Smeets F, Gunther N, van Zelst C, de Graaf R, ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S, Bak M, Myin-Germeys I, Viechtbauer W, van Os J, van Winkel R (2014) Psychopathological mechanisms linking childhood traumatic experiences to risk of psychotic symptoms: analysis of a large, representative population-based sample. Schizophrenia Bull 40:123–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/Schbul/Sbt150

Kelleher I, Keeley H, Corcoran P, Ramsay H, Wasserman C, Car V, Sarchiapone M, Hoven C, Wasserman D, Cannon M (2013) Childhood trauma and psychosis in a prospective cohort study: cause, effect, and directionality. Am J Psychiat 170(7):734–741. https://doi.org/10.1176/Appi.Ajp.2012.12091169

Mørkved N, Mathilde E, Winje D, Johnsen E, Dovran A, Arefjord K, Kroken RA, Helle S, Anda-Ågotnes L-G, Rettenbacher MA, Huber N, Løberg EM (2016) Childhood maltreatment trauma in non-affective psychosis as compared to other mental health disorders. BMC Psychiatry

McGrath JJ, McLaughlin KA, Saha S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Jonge P, Esan O, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam EG, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, Lepine JP, Lim CC, Medina-Mora ME, Mneimneh Z, Pennell BE, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Sampson N, Viana MC, Xavier M, Bromet EJ, Kendler KS, Kessler RC (2017) The association between childhood adversities and subsequent first onset of psychotic experiences: a cross-national analysis of 23 998 respondents from 17 countries. Psychol Med 47(7):1230–1245. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003263

Spauwen J, Krabbendam L, Lieb R, Wittchen HU, van Os J (2006) Impact of psychological trauma on the development of psychotic symptoms: relationship with psychosis proneness. Br J Psychiat 188:527–533. https://doi.org/10.1192/Bjp.Bp.105.011346

Heins M, Simons C, Lataster T, Pfeifer S, Versmissen D, Lardinois M, Marcelis M, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L, van Os J, Myin-Germeys I, Project G (2011) Childhood trauma and psychosis: a case-control and case-sibling comparison across different levels of genetic liability, psychopathology, and type of trauma. Am J Psychiatry 168(12):1286–1294. https://doi.org/10.1176/Appi.Ajp.2011.10101531

Ucok A, Bikmaz S (2007) The effects of childhood trauma in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 116(5):371–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01079.x

van Nierop M, van Os J, Gunther N, van Zelst C, de Graaf R, Ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S, Bak M, Myin-Germeys I, van Winkel R (2014) Does social defeat mediate the association between childhood trauma and psychosis? Evidence from the NEMESIS-2 Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 129(6):467–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12212

Lataster T, Van Os J, Drukker M, Henquet C, Feron F, Gunther N, Myin-Germeys I (2006) Childhood victimisation and developmental expression of psychotic experiences. Schizophr Res 81:181–182

Pontillo M, De Luca M, Pucciarini ML, Vicari S, Armando M (2016) All that glitters is not gold: prevalence and relevance of psychotic-like experiences in clinical sample of children and adolescents aged 8–17 years old. Early Interv Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12370

Robustelli BL, Newberry RE, Whisman MA, Mittal VA (2017) Social relationships in young adults at ultra high risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Res 247:345–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.008

Alderman T, Addington J, Bearden C, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Cadenhead KS (2015) Negative symptoms and impaired social functioning predict later psychosis in Latino youth at clinical high risk in the North American prodromal longitudinal studies consortium. Early Interv Psychiatry 9(6):467–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12128

Cornblatt BA, Carrion RE, Auther A, McLaughlin D, Olsen RH, John M, Correll CU (2015) Psychosis Prevention: A Modified Clinical High Risk Perspective From the Recognition and Prevention (RAP) Program. Am J Psychiatry 172(10):986–994. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.13121686

Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ (2008) Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry 165(5):579–587. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081242

Kahn RS, Keefe RS (2013) Schizophrenia is a cognitive illness: time for a change in focus. JAMA Psychiatry 70(10):1107–1112. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.155

Woodberry KA, Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Verdi MB, Cook WL, McFarlane WR (2010) Neuropsychological profiles in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: relationship to psychosis and intelligence. Schizophr Res 123(2–3):188–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.06.021

Brewer WJ, Francey SM, Wood SJ, Jackson HJ, Pantelis C, Phillips LJ, Yung AR, Anderson VA, McGorry PD (2005) Memory impairments identified in people at ultra-high risk for psychosis who later develop first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 162(1):71–78. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.71

Nieman DH, Ruhrmann S, Dragt S, Soen F, van Tricht MJ, Koelman JH, Bour LJ, Velthorst E, Becker HE, Weiser M, Linszen DH, de Haan L (2014) Psychosis prediction: stratification of risk estimation with information-processing and premorbid functioning variables. Schizophr Bull 40(6):1482–1490. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt145

Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Meyer EC, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Bearden CE, Christensen BK, Hawkins K, Heaton R, Keefe RS, Heinssen R, Cornblatt BA, North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study G (2010) Neuropsychology of the prodrome to psychosis in the NAPLS consortium: relationship to family history and conversion to psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(6):578–588. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.66

De Herdt A, Wampers M, Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Vanhees L, Demunter H, Van Bouwel L, Brunner E, Probst M (2013) Neurocognition in clinical high risk young adults who did or did not convert to a first schizophrenic psychosis: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 149(1–3):48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.017

Smith B, Fowler DG, Freeman D, Bebbington P, Bashforth H, Garety P, Dunn G, Kuipers E (2006) Emotion and psychosis: links between depression, self-esteem, negative schematic beliefs and delusions and hallucinations. Schizophr Res 86(1–3):181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.018

Barrowclough C, Tarrier N, Humphreys L, Ward J, Gregg L, Andrews B (2003) Self-esteem in schizophrenia: relationships between self-evaluation, family attitudes, and symptomatology. J Abnorm Psychol 112(1):92–99

Romm KL, Rossberg JI, Hansen CF, Haug E, Andreassen OA, Melle I (2011) Self-esteem is associated with premorbid adjustment and positive psychotic symptoms in early psychosis. BMC Psychiatry 11:136. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-136

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215

Schmidt SJ, Grunert VM, Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C (2014) Differences in coping, self-efficacy, and external control beliefs between patients at-risk for psychosis and patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res 219(1):95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.045

Bird V, Premkumar P, Kendall T, Whittington C, Mitchell J, Kuipers E (2010) Early intervention services, cognitive-behavioural therapy and family intervention in early psychosis: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 197(5):350–356. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074526

Finnegan D, Onwumere J, Green C, Freeman D, Garety P, Kuipers E (2014) Negative communication in psychosis: understanding pathways to poorer patient outcomes. J Nerv Ment Dis 202(11):829–832. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000204

O'Brien MP, Gordon JL, Bearden CE, Lopez SR, Kopelowicz A, Cannon TD (2006) Positive family environment predicts improvement in symptoms and social functioning among adolescents at imminent risk for onset of psychosis. Schizophr Res 81(2–3):269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.10.005

Hysing M, Harvey AG, Linton SJ, Askeland KG, Sivertsen B (2016) Sleep and academic performance in later adolescence: results from a large population-based study. J Sleep Res 25(3):318–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12373

Larøi F, Marczewski P, Van der Linden M (2004) Further evidence of the multi-dimensionality of hallucinatory predisposition: factor structure of a modified version of the Launay-Slade Hallucinations Scale in a normal sample. Eur Psychiatry 19(1):15–20

Preti A, Sisti D, Rocchi MBL, Siddi S, Cella M, Masala C, Petretto DR, Carta MG (2014) Prevalence and dimensionality of hallucination-like experiences in young adults. Compr Psychiatry 55:826–836

Aleman A, Nieuwenstein MR, Böcker KB, De Haan EH (2001) Multi-dimensionality of hallucinatory predisposition: factor structure of the Launay-Slade Hallucination Scale in a normal sample. Personality Individ Differ 30(2):287–292

Waters FA, Badcock JC, Maybery MT (2003) Revision of the factor structure of the Launay-Slade Hallucination Scale (LSHS-R). Pers Individ Dif 35(6):1351–1357

Larøi F, Van Der Linden M (2005) Nonclinical Participants' Reports of Hallucinatory Experiences. Can J Behav Sci 37(1):33

Lien L, Halvorsen JA, Haavet OR, Dalgard F (2012) The relation of early experienced negative life events and current itch. A longitudinal study among adolescents in Oslo. Norway. J Psychosom Res 72(3):226–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.12.001

Olweus D, Limber SP (2010) Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am J Orthopsychiatry 80(1):124–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x

Askeland KG, Sivertsen B, Skogen JC, La Greca AM, Tell GS, Aarø LE, Hysing M (2017) Alcohol and drug use among internationally adopted adolescents: results from a norwegian population-based study. Am J Orthopsychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000231

Madge N, Hewitt A, Hawton K, Wilde EJd, Corcoran P, Fekete S, Kv Heeringen, Leo DD, Ystgaard M (2008) Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: comparative findings from the child and Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(6):667–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01879.x

Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M (1999) Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolescent Psychiatry 38(10):1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011

von Soest T, Mossige S, Stefansen K, Hjemdal O (2010) A validation study of the resilience scale for adolescents (READ). J Psychopathol Behav Assess 32(2):215–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9149-x

Kessler RC, Adler LA, Gruber MJ, Sarawate CA, Spencer T, Van Brunt DL (2007) Validity of the World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Screener in a representative sample of health plan members. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 16(2):52–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.208

Goodman R (1999) The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(5):791–799

Thapar A, McGuffin P (1998) Validity of the shortened Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in a community sample of children and adolescents: a preliminary research note. Psychiat Res 81(2):259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00073-0

Posserud MB, Breivik K, Gillberg C, Lundervold AJ (2013) ASSERT–the autism symptom SElf-ReporT for adolescents and adults: bifactor analysis and validation in a large adolescent population. Res Dev Disabil 34(12):4495–4503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.09.032

Corp IBM (2015) IBM SPSS statistics for windows Version 230. IBM Corp, Armonk

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2015) Mplus 7.4. Muthén & Muthén, 3463 Stoner Avenue, CA 90066, Los Angeles

Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS (2003) Applied multiple regression—correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 3rd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc, New York

Waters F, Allen P, Aleman A, Fernyhough C, Woodward TS, Badcock JC, Barkus E, Johns L, Varese F, Menon M, Vercammen A, Larøi F (2012) Auditory Hallucinations in Schizophrenia and Nonschizophrenia Populations: A Review and Integrated Model of Cognitive Mechanisms. Schizophrenia Bull 38(4):683–693. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs045

Maijer K, Steenhuis LA, Lotgering R, Palmen SJMC, Sommer IEC, Bartels-Velthuis AA (2018) Clinical significance of auditory hallucinations in youth: comparison between a general population and a help-seeking sample. Schizophr Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.07.027

Norway SsS (2018) Facts about education in Norway 2018: Key figures 2016.

Acknowledgements

The current study did not receive any funding. The data is from the Bergen Child Study (BCS), conducted by the Regional Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Welfare in collaboration with Hordaland County Council. This project was funded by the Norwegian Directorate for Health and Social Affairs, University of Bergen, and the Western Norway Regional Health Authority. We are grateful to the children, parents, and teachers participating in the BCS, as well as present and previous members of the BCS project group for making the study possible. A special thanks to Professor Christopher Gillberg who initiated the study, and to Anna Spyro for proofreading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards:

All human studies have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The manuscript does not contain animal data. All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Løberg, EM., Gjestad, R., Posserud, MB. et al. Psychosocial characteristics differentiate non-distressing and distressing voices in 10,346 adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28, 1353–1363 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01292-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01292-x