Abstract

Planning is critical for negotiation success as it facilitates obtaining superior outcomes. However, little empirically is known about this topic. We argue that individual differences are important to understanding planning behavior because planning affords greater opportunities for individual differences to manifest compared to other phases of negotiation. We conducted a series of studies with the aim of understanding how the Big Five factors and gender predict information search and preference while planning. In Study 1, we examined information search behavior using the Mouselab paradigm. When the search space was large, agreeableness predicted persistence in search, and women spent significantly more time on the task, and looked for value creating and relationship related information to a greater extent than men (Study 1a). In a more constrained situation or with a smaller search space, few associations between individual differences and search behavior emerged (Studies 1b and 1c). In Study 2, we used a survey design to elicit preferences for information type. In this task, multiple personality factors predicted preferences. Conscientiousness and openness predicted preferences for value claiming information, and women preferred value creating information. Conscientiousness predicted preference for value claiming choice of information through the preference for value claiming information. How individual differences manifest in information search and preference in negotiation planning is a function of both task type and complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Planning is essential to effective negotiation. Both academics and expert practitioners advise negotiators to gather information before the first offer is made (American Bar Association 2009; Kennan and Mearsheimer 2012; Schneider and Honeyman 2006). Information gathered prior to bargaining can be a source of advantage—negotiators informed about the counterpart’s limits often claim greater value (Galinsky and Mussweiler 2001). But the dominant form of research continues to be simulation based methods that assume equivalence in planning (Jang et al. 2018; Pruitt 2012). Thus, we know little about how people search for and evaluate information as they plan. In this research, we adopt an individual differences perspective. This approach assumes there are measurable and stable between-person differences that can predict both behavior and outcomes. For example, personality reflects an individual’s preferred way of being across social situations (Fleeson 2004), and it has been informative in predicting a wide array of consequential life outcomes (Borghans et al. 2008).

We focus on the Big Five personality factors and gender because they represent some of the most widely studied individual differences in negotiation (see Elfenbein 2015 for a review; Boothby et al. 2022; Mazei et al. 2015; Sharma et al. 2013). Prior thinking about planning describes gender and psychological characteristics as major influences on planning and negotiation more generally (Peterson and Lucas 2001; Stuhlmacher and Adair 2011). In addition, the Big Five and gender are relevant to negotiation planning because they predict conceptually similar behaviors. For example, conscientiousness predicts greater investment behavior and maintaining a balance of liquid and illiquid assets, which help to increase overall net worth (Letkiewicz and Fox 2014), and women spend less time planning and saving for retirement (Glass and Kilpatrick 1998; Jacobs-Lawson et al. 2004).

To establish the initial insights about how people plan, we aimed to study the association between the Big Five personality factors, gender, and information search. We also aimed to explore boundary effects because the expression of individual differences depends on the characteristics of the situation (Robbins et al. 2017). Situational strength theory suggests that situational constraints may restrict the expression of individual differences (Meyer and Dalal 2009), indicating a role for constraint in attenuating individual differences. Furthermore, trait activation theory proposes that some situations and tasks trigger the expression of a particular trait (Tett and Burnett 2003), indicating the role of task type in eliciting individual difference expression. By systematically varying situational factors and task types, we aim to better understand how individual differences play a role in the planning process. To achieve this, we deployed the Mouselab paradigm in Study 1 to simulate the information search task while varying the complexity and constraints to measure the effects of personality and gender on the search behavior and preferences. In Study 2, we deployed a survey-based task which required much less effort.

1.1 Information Search in Planning

Negotiation planning is defined as actions before the first offer that facilitate desirable outcomes (Hayes-Roth and Hayes-Roth 1979). Expert practitioners regard it as central to effective negotiation (Roloff et al. 2003), and experienced diplomats can spend up to 75% of their time planning (Zartman 2006). Despite its import in the field, planning is poorly understood in the academic negotiation literature, with little empirical research on the topic (Jang et al. 2018). To our knowledge, there is little theory and data on how negotiators plan. To address this gap, we seek to generate stylized facts about behavior in the planning phase.

We focus on information search in planning. Peterson and Lucas (2001) define it as the process of gathering, sorting, evaluating, and analyzing information about the negotiation. Information search may often be the initial step and may inform subsequent actions,Footnote 1 such as strategy formulation and planned action sequences. In dynamic phase models of negotiation, negotiators search for multiple kinds of information prior to bargaining, which shapes the course of bargaining and possible agreements (Gulliver 1979). Theory suggests negotiators can search for three kinds of information. Thompson’s (1990) taxonomy suggests negotiators can value their share of the outcome, the creation of additional value, and their relationship with the counterpart. Understanding how negotiators secure information related to these goals will furnish the field with insights that inform theory.

1.2 The Role of Personality and Gender on Information Search

Individual differences have the potential to reveal how people search for information while planning. This is because information search is often an individual activity, which implies much less interpersonal interaction compared to bargaining. In contrast, bargaining is a fundamentally interpersonal activity. It has been likened to a dance, involving a sequence of proposals and questioning in response to counterpart actions (Adair and Brett 2005). In that phase, the counterpart should have substantial influence over thoughts and actions, and the expression of individual differences should be less apparent when compared to the planning phase. To illustrate, a study that examined affective experiences among dyads showed only about 20–30% of the variability was explained by one’s own set of traits, while about 60%, or the vast majority of the variability, was explained by the unique relationship between the self and the other (Eisenkraft and Elfenbein 2010). Because planning often features a lack of interaction with a counterparty that may have opposing preferences, this affords one’s own traits the opportunity to substantively predict planning behavior.

We adopted the Big Five model in studying individual differences in information search. The Big Five is a comprehensive model of personality (Costa and McCrae 1992a) and has been used to study individual differences in negotiation research (Sharma et al. 2013). To formulate hypotheses, we focused on personality and gender because evidence suggests their role in predicting planning behavior in other literatures. For example, conscientious people tend to outperform their peers in activities that demand substantial planning skills, such as health outcomes (Molloy et al. 2014) and asset accumulation (Letkiewicz and Fox 2014). We also draw on research on personality in the bargaining phase with the assumption that what is known about personality in the bargaining phase generalizes to the planning phase. We justify this on the basis that personality research shows traits to predict behavior consistently across contexts (Fleeson 2004; Mischel and Shoda 1995; Paunonen 1998; Paunonen et al. 2003). For example, conscientious people tend to perform better at school (Chamorro-Premuzic and Furnham 2005) and at work (Barrick and Mount 1991). We also recognize that what is observed in the bargaining phase has no direct analogue to what might happen in planning, such as building an interpersonal relationship with the counterparty. But many actions in the bargaining phase can have their start in the planning phase—attempts to claim value can manifest in a favorable first offer, and this can be facilitated by searching for the counterpart's reservation price in the planning phase. Both can be driven by a high level of achievement striving, an aspect of conscientiousness. In the following sections, we develop hypotheses about the potential role of each factor given what we know about in research to date.

Extraversion reflects tendencies to be assertive, gregarious, and sociable (Costa and McCrae 1992a). The trait is associated with greater information sharing about preferences during bargaining (Barry and Friedman 1998; Dimotakis et al. 2012). Thus, extraversion is associated with creating value as it facilitates information exchange and discovery of tradeoffs (Barry and Friedman 1998; Ma and Jaeger 2005). However, the tendency to share information about limits hinders the ability to claim value (Amanatullah et al. 2008; DeRue et al. 2009).

H1

Extraversion is positively correlated with

-

(a)

search for value creating information,

-

(b)

value creating choices, and

-

(c)

preference for value creating information.

Agreeableness reflects tendencies to be altruistic, generous, warm, and cooperative (Costa and McCrae 1992a; John and Srivastava 1999). The trait is associated positively with interpersonal relationships and negatively with conflict, challenging others’ ideas, and participating in competitive tasks (Graziano et al. 1996). Consistent with this, agreeable negotiators are often concerned with relationships and the interests of others, as the trait predicts accommodating counterparts (Barry and Friedman 1998; Cable and Judge 2003). Agreeable negotiators also focus less on their own needs and make concessions in exchange in order to improve the relationship (De Dreu and Van Lange 1995; Messick and McClintock 1968).

H2

Agreeableness is positively correlated with

-

(a)

search for relationship-building information,

-

(b)

relationship-building choices, and

-

(c)

preference for relationship-building information.

Conscientiousness reflects tendencies to be planful, achievement-oriented, and task-focused (McCrae and John 1992). Conscientiousness is more strongly associated with goal accomplishment than socioemotional involvement (Aronoff and Wilson 2014) and creativity (Feist 1998), suggesting its role in value claiming. Being achievement-oriented and task-focused should facilitate progress towards achieving negotiation objectives. This is supported by findings that show the trait to be associated with higher performance in sales contexts, where negotiation is a required skill (Barrick et al. 2002), and correlated with individual gain in negotiation (Barry and Friedman 1998).

H3

Conscientiousness is positively correlated with

-

(a)

search for value claiming information,

-

(b)

value claiming choices, and

-

(c)

preference for value claiming information.

Neuroticism reflects the tendency to experience negative emotions (Costa and McCrae 1992a; John and Srivastava 1999). Neuroticism is associated with higher face threat sensitivity, which leads to a higher rate of impasse and lower joint value (White et al. 2004). It also predicts competitive behaviors and deploying exploitative tactics to elicit concessions (Alexander et al. 1994; Carnevale and De Dreu 2006). The trait is unlikely to be implicated in value creation through information sharing, as it is associated with lower motivation to learn new information (Brown and O’Donnell 2011).

H4

Neuroticism is positively correlated with

-

(a)

search for value claiming information,

-

(b)

value claiming choices, and

-

(c)

preference for value claiming information.

Openness reflects a tendency to be curious, open-minded, imaginative, and creative (Costa and McCrae 1992b). Openness should lead to less zero-sum bargaining and more willingness to work towards integrative solutions (Sharma et al. 2013). Because the trait is associated with divergent thinking and information sharing in groups (Barrick and Mount 1991; Krasman 2010), it should facilitate more cooperative behaviors and greater mutual gains in negotiation (Ma and Jaeger 2005; Sharma et al. 2013). In addition, the tendency to be more flexible and pursue unconventional ideas associated with openness also facilitates more value creating activities (Ma and Jaeger 2005).

H5

Openness is positively correlated with

-

(a)

search for value creating information,

-

(b)

value creating choices, and

-

(c)

preference for value creating information.

We also examined if gender influences information search. Research on gender differences in bargaining suggests men have greater value claiming tendencies than women. Compared to women, men set higher targets (Bowles et al. 2005), focused more on economic outcomes (Trapnell and Paulhus 2012), made more extreme first offers (Barron 2003; Galinsky and Mussweiler 2001), and were less cooperative (Walters et al. 1998). Kulik and Olekalns (2012) concluded that women are less demanding, more accommodating, and more willing to make generous offers than men in negotiation. Moreover, a meta-analysis by Mazei and colleagues (2015) also showed that men engaged more in competitive behaviors (Walters et al. 1998) and achieved better economic outcomes (Amanatullah and Morris 2010; Stuhlmacher and Linnabery 2013).

H6

Women are

-

(a)

less likely to search for value claiming information,

-

(b)

less likely to make value claiming choices, and

-

(c)

likely to have lower preference for value claiming information.

We provide a summary of the derived hypotheses in Table 1.

1.3 Situational Constraint and Information Search

Situational constraint can explain how individual differences manifest in negotiation planning. Negotiators search for information in a wide variety of situations. In some situations, they may need to expend considerable effort to secure information. At other times, they may be able to request a subordinate to complete the task. Information search is subject to constraint, and the constraint could moderate how personality is expressed. Situational strength theory posits that the expression of individual differences, such as personality and gender, can be attenuated when constraints are present (Meyer and Dalal 2009). For example, the level of autonomy afforded to employees and resource constraints can limit how individual differences are expressed in a performative task. In support of this idea, jobs higher in restraint exhibited lower variability in outcomes (Meyer et al. 2010). Negotiators can face such constraints, as there may be limited time or budget that constrains the length and extent of the search, or a lack of information available in the environment may mean the extensive search is not possible. So greater constraint could lead to attenuated relationships between personality, gender, and search behavior. In our studies, we model this constraint and examine the boundary effects of individual differences on the search behavior and preferences by varying the size of the search space and the extent of search allowed.

1.4 Overview of Studies

The aim of Study 1 was to examine how personality and gender impact information search when it is effortful. To simulate effortful search, we used the Mouselab paradigm (Johnson et al. 1989), an experimental method to study decision-making (Schulte-Mecklenbeck et al. 2017; Willemsen and Johnson 2011). Mouselab originated from information display boards (IDB), a tool for measuring information search behavior (Payne 1976). An IDB is a set of index cards arranged in a matrix. Information about a decision is written on the back of each card, away from view. To reveal information, participants need to turn over a card. Before other information is revealed, the revealed card must be turned away. Mouselab is a digital representation of this design. Participants inspect the virtual cards by clicking on them (see Fig. 1). This paradigm is used to study decision-making involving multiple attributes. For example, it was used to capture the relationship between social value orientation and information acquisition (Bieleke et al. 2020).

Mouselab records the kind of information sought, the sequence of the search, time spent on the task, and final decisions made (Johnson et al. 1989). The frequency of clicks and the duration spent on a panel indicate the levels of attention and preference for the type of information (Chen and Fischbacher 2016; Schkade and Johnson 1989). Total clicks and the total time spent on exploring panels represent the level of effort or persistence in the search task (Li et al. 2020; Schkade and Johnson 1989). The final choice indicates the prospect with the greatest utility (Goldstein and Einhorn 1987; Yang et al. 2015).

Information search in Mouselab is effortful because information is not presented in a linear narrative. Instead, information is hidden and presented in a randomized matrix. Participants must decide for themselves what information they deem relevant to explore, memorize details of the information revealed, and then formulate a mental model of the situation based on their choices. It requires a comparatively higher level of effort than reading instructions for a typical simulation.

We deployed different versions of the Mouselab paradigm that varied in complexity and constraint. For Studies 1a and 1b, we deployed an information matrix with 18 elements as in Figs. 1 and 2, and simplified this to six elements for Study 1c, as in Fig. 3. This allowed us to examine the effect of complexity. In addition, we varied the level of constraint, by placing restrictions on the number of clicks and search duration in Studies 1b and 1c. This allowed us to model the effect of costly search.

We conducted secondary analyses on search patterns to examine the effect of search complexity. Complex situations can lead people to adopt simplifying heuristics (Chaiken and Ledgerwood 2012). They can greatly simplify the amount of effort required to process information, such as relying on consensus to determine the correctness or equating argument length with argument strength (Chaiken and Ledgerwood 2012). In a complex search task involving a matrix, we reasoned that a pattern involving typical reading patterns (i.e., progressing from top right to top left) could be evident when the search space is large and no constraints are present. Such patterns should be less evident when negotiators are constrained and so must be deliberate in looking for information.

While the paradigm provides objective information about effortful search behaviors, it is not a complete representation of the search process. In some cases, searching may involve delegating the task to others. The relative lack of effort in such situations may provide greater latitude for personality and gender to be expressed. We conducted Study 2 to examine this possibility by deploying a survey method. We intended for the task to entail little effort, such as when lead negotiators or managers direct subordinates to gather information.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

2.1.1 Study 1

For all studies, we recruited participants from Prolific who were compensated $2.60 USD. The minimum sample size of N = 300 was selected in each study to have 80% power to detect a correlation of .16 at a significance level of .05, calculated using G*Power (Cohen 1988; Denis 2019). For Study 1a, 305 participants (54.75% female, age M = 34.45, SD = 12.46) were recruited. Five participants were excluded due to incomplete responses, leaving a final sample of 300. For Study 1b, 300 participants (43.33% female, age M = 31.48, SD = 11.74) were recruited. Two participants were omitted from the analyses due to incomplete responses, leaving a final sample of 298. For Study 1c, 325 participants (46.77% female, age M = 34.66, SD = 13.35) were recruited. Participants who used incompatible devices, experienced technical difficulties, did not provide complete responses, or provided responses with zero variance were excluded, leaving a final sample of 288.

2.1.2 Study 2

We recruited 309 participants from Prolific (46.92% female, age M = 34.28, SD = 13.91) who were compensated $1.83 USD. The sample size was selected as in Study 1. We excluded participants who failed attention checks, provided personality data with zero variance, and spent less than three minutes on the survey, leaving a final sample of 300.

2.2 Procedure

2.2.1 Study 1

Across all studies, participants first completed a Big Five personality measure. They were then briefed about a negotiation situation based on the Biopharm-Seltek exercise (Greenhalgh 2001). They assumed the role of a Chief Financial Officer who would negotiate the purchase of a factory to take place in the following week. They needed to purchase a government-certified factory to produce an antibiotic compound. As there was limited available information about the counterpart, they would need to purchase it. They could do so from one of three consulting firms, but due to budget restrictions, they could only purchase one dossier. Participants were then shown the virtual information board (Studies 1a, 1b—Fig. 1; Study 1c—Fig. 2), after a familiarization task. They were told that they could reveal information hidden below opaque panels. After inspecting the matrix, they could select the dossier that would most help them in their negotiation. In Study 1a, participants had unlimited time and clicks to examine information in the matrix. In Studies 1b and 1c, they were restricted to six clicks and 5 min. After selecting the information package to purchase, they provided demographic information.

2.2.2 Study 2

After providing consent, participants completed a Big Five personality measure. Next, they were briefed about a hypothetical negotiation situation. The negotiation situation was similar to Study 1, but instead of purchasing a dossier, they would direct subordinates to obtain information. The participants completed a comprehension check to ensure that they understood the task. Then participants indicated the importance of six kinds of information, two each relating to value claiming, value creating, and relationship, as in Study 1a and 1b. After rating the importance of each piece of information, they made a single choice about which of the six was most important and provided demographic information.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Personality

The 30-item short form of the Big Five Inventory–2 (BFI-2-S) (Soto and John 2017) was used to measure the Big Five personality factors. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha across all studies were acceptable (Extraversion = .74–.80, agreeableness = .75–.79, conscientiousness = .80–.83, neuroticism = .85–.88, and openness = .77–.81).

2.3.2 Study 1: Information Matrix

In Studies 1a, 1b, and 1c, we presented a matrix that represented dossiers from three consulting firms. Information was obscured with an opaque grey panel, labeled with the type of information contained. When participants clicked on a panel, information would be revealed, and it reverted to being opaque when they moved their mouse away. For Studies 1a and 1b, one firm offered two pieces of information regarding value claiming (i.e., value of the land and insurance value of the building). Another provided two pieces of value-creating information (i.e., additional opportunities and potential collaborative projects). And the final firm supplied information about relationship building (i.e., behaviors in prior deals and counterpart’s personality and interests). This design meant that the search would take some time to complete, each dossier provided unique information, and there was no ambiguity about the specialization each firm offered. A full description of the information available is shown in Fig. 2. For Study 1c, we simplified this to a single piece of information, as in Fig. 3. We chose the more frequently chosen option, as observed in Study 1b, to minimize selection due to the perception of less relevance. The presentation of the columns and rows was fully randomized. We designed the study using MouselabWEB (Willemsen and Johnson 2008). Studies 1a, 1b, and 1c were designed to test hypotheses regarding personality and gender on information search (H1a–H6a) and choice of information (H1b–H6b).

2.3.3 Study 2: Information Preference and Choice

In Study 2, we developed six items about the negotiation situation that participants could prioritize for their subordinates to search, resembling information provided in Study 1. Two items related to value claiming, two related to value creating, and two related to relationships as shown in Fig. 4. Items were presented in a random order, and none of them were labelled with the category they represented. Participants indicated importance on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = extremely unimportant to 7 = extremely important). For the three categories of information, we averaged ratings across the two items, given a substantial correlation for pairs of value claiming (r = .34, p < .01), value creating, (r = .50, p < .01), and relationship information (r = .41, p < .01). After indicating their preference, we listed the six pieces of information again on a new screen, as shown in Fig. 5. We then asked participants to select a single piece of information that was most important. Study 2 was designed to test hypotheses regarding personality and gender on choice of information (H1b-H6b) and information preference (H1c-H6c).

3 Results

3.1 Personality and Gender in Effortful Search

Tables 2, 3, and 4 show descriptive statistics and correlations between major variables for Studies 1a, 1b, and 1c respectively. Across studies, there were few associations between personality traits and search behavior. In Study 1a, extraversion negatively correlated with time spent and clicks on value creating panels, relationship panels, total clicks, and total time spent on the task. Agreeableness correlated with more time spent on value claiming panels. Women spent more time on value creating panels, relationship panels, and overall time spent on the task. In Study 1b where constraints were present, neuroticism correlated with less time spent overall, and conscientiousness correlated with less time spent on value creating panels. In Study 1c with constraints and a simplified matrix, neuroticism correlated with fewer clicks on value claiming panels. Gender did not correlate with any of the search behaviors in Studies 1b and 1c.

3.1.1 Time Spent Inspecting Panels

We examined the amount of time participants spent inspecting each type of panel, as well as the overall time spent on the matrix, with the results in Table 5. Higher extraversion predicted less time spent on searching and on each type of panel in Study 1a, where the search task is complex, search space is large, and there are no constraints on behavior. Higher agreeableness predicted greater effort and time spent on inspecting value claiming information. Female negotiators spent significantly more time searching for value creating information, relationship information, and total time searching in Study 1a.

Some counterintuitive relationships also emerged. In Study 1a and 1b, higher neuroticism predicted less total time on the matrix. The trait predicted less time spent on inspecting relationship information only when the task was complex (Study 1a). Openness negatively correlated with time spent on inspecting value creating information when the task was complex and constrained (Study 1b). There were no significant relationships between personality and time spent when the task was simple, and there were constraints on behavior (Study 1c). None of the hypotheses regarding personality, gender, and information search (H1a-H6a) were supported.

3.1.2 Clicks on Type of Information

We examined the number of clicks on each type of information panel, as well as the total number of clicks, with the results shown in Table 6. For Studies 1a and 1b, we estimated negative binomial regressions due to overdispersion, but this was not an issue for Study 1c, so we estimated Poisson regressions. When the search task was complex and there were no constraints (Study 1a), agreeableness predicted greater clicks on value creating panels, value claiming panels, and the information matrix overall. By contrast, extraversion predicted fewer clicks across three types of information panels and fewer overall clicks (Study 1a). Although the results were contrary to our expectations, they were similar to the results on search time. Personality did not predict clicks when constraints were present (Studies 1b and 1c). Gender did not predict clicks across all three studies. None of the hypotheses regarding personality, gender, and information search (H1a–H6a) were supported.

3.1.3 Choice of Dossier

We next examined the dossiers participants chose following the search. The most chosen dossier in Study 1a was the value claiming dossier (41%), while the dossier emphasizing relationships was most chosen in Study 1b (36%) and Study 1c (45%). The least chosen in Study 1a (21%) and 1b (31%) was the value creating dossier, and in Study 1c, it was the value claiming dossier (23%). The results of multinomial regressions are shown in Table 7. In a complex search task with no constraint, openness was associated with a greater likelihood of choosing a value claiming dossier relative to a value creating one (Study 1a), but this effect was only marginally significant when constraints were introduced (Study 1b).

Openness was also associated with choosing a relationship information-oriented dossier relative to a value creating dossier in a complex and constrained search task (Study 1b). Personality did not predict choice when the situation was simple, and constraints were present (Study 1c). Gender did not predict choice. None of the hypotheses regarding personality, gender, and information choice (H1c–H6c) were supported.

3.1.4 Click Distribution and Initial Search Patterns

We looked for patterns in search behavior by tabulating the frequency clicks on each panel, as shown in Table 8. We also examined the first three clicks on panels to examine if negotiators engaged in a search that mimics reading, namely their first click starting on the top leftmost panel, then moving horizontally to the right. This would indicate the search was not targeted toward any specific information, since rows and columns were randomized.

Distinct search patterns appeared across studies. When there was no constraint on behavior and the task was complex (Study 1a), the clicks were uniformly distributed across information types. About a quarter (24%) followed a reading pattern, suggesting a sizable portion of negotiators did not start their search with a specific type of information in mind. When the task was complex and constraints were present (Study 1b), we observed a more targeted approach, with the majority of clicks concentrated on one piece of information within each category. The reading pattern was much less prevalent with only 6% of participants doing so. When the task was simple and constraints were present (Study 1c), the clicks were more evenly distributed, and a substantial number of participants (22%) started their search from the top left panel and moved to the right for their first three clicks. If negotiators are provided the opportunity to examine the entire search space (Study 1a), or the vast majority of it (Study 1c), they will start with the first item and work their way through each item. If the constraint means they cannot search most of the search space, their search is more targeted in the form of sampling across information type. These patterns suggest constraints can induce heuristic search patterns.

3.2 Personality and Gender in Less Effortful Search

Descriptive statistics and correlations for Study 2 are shown in Table 9. Value claiming information was given greatest importance, followed by relationship, and value creating information, in terms of both ratings and final choice. Preferences correlated with final choice. On a bivariate level, women chose relationship information to a greater extent than men.

3.2.1 Information Preference

In Study 2, with the exception of extraversion and agreeableness, the Big Five traits and gender predicted information preference. We estimated a series of linear regressions with preferences for types of information as dependent variables and personality and gender as predictors. Results are shown in Table 10. Conscientiousness and openness were positively associated with a preference for value claiming information, supporting H3c. Extraversion did not predict preference for value creating information, and agreeableness did not predict relationship information, rejecting H1c and H2c. Female negotiators preferred value creating information to a greater extent than men.

3.2.2 Choice of Information

In Study 2, individual differences did not predict choice of information. Table 11 shows the results of multinomial logistic regressions. None of the hypotheses regarding personality, gender, and information choice (H1c–H6c) were supported.

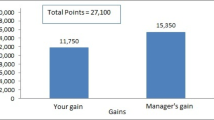

3.2.3 Additional Analyses

Although some of the Big Five traits and gender predicted information preferences, they played no role in predicting the choice of information. In some cases, personality predicted a type of information, which in turn predicted a corresponding choice. Because we measured those variables in that sequence, we tested mediation models with personality as the independent variable, preferences as the mediating variable, and choice as the dependent variable using the Monte Carlo method (Selig and Preacher 2008). We found support for one model. There was a significant indirect effect of conscientiousness predicting value claiming choice through value claiming preferences (indirect effect = .24, 95% CI = .03–.49), as shown in Fig. 6. In this model, we controlled for the remaining Big Five factors and gender. Further exploring such relationships remains a topic for future research.

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of Findings

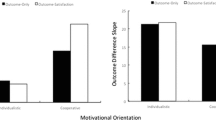

We aimed to describe how negotiators search for information while planning to negotiate. In Study 1a, we observed both personality and constraint to influence search patterns in unexpected ways. Where the search space was large, task was complex, and without constraints, agreeableness predicted search persistence, in terms of both duration and number of clicks. We interpret this to mean that when asked to engage in a relatively complex search task, agreeable people complied with instructions. In contrast, the less effortful task in Study 2 produced trait consistent preferences for different kinds of information. For example, conscientiousness predicted preference for value claiming information, reflecting tendencies to be achievement striving. This pattern of results is consistent with trait activation theory (Tett and Burnett 2003), in that different tasks elicited distinct patterns of trait consistent behavior. The overall pattern of our findings was also consistent with situational strength theory (Meyer and Dalal 2009). In Study 1a, personality and gender predicted behavior where there were no restrictions on their time or ability to click. However, this tendency was not observed in Studies 1b and 1c when situational constraints limited the expression of individual differences.

Gender and constraint were also found to influence search patterns. In Study 1a, women were more persistent and searched for value creating and relationship related information to a greater extent than men. This is relatively consistent with social role theory which posits that women are more relationship-oriented, accommodating, and concerned about others’ welfare (Eagly and Wood 2012). However, the effect of gender on search behaviors were not significant when constraints were imposed (Study 1b, and 1c). In Study 2, women prioritized value creating information, when the task was simple.

We also observed some counterintuitive relationships. Despite being associated with value creation (Barry and Friedman 1998; Sharma et al. 2013), openness predicted less time searching for value creating information when the task was complex and constrained. The trait was associated with choice for value claiming and relationship dossiers than the value creating counterpart in a complex search task. In addition, extraversion predicted fewer clicks and less time spent on value creating information, and less time overall, when the task was complex and unconstrained. Finally, neuroticism predicted less time spent on the task when it was complex. Because none of these patterns are supported by hypotheses, we can only speculate about their nature. In the case of both openness and extraversion, they could still yet predict trait consistent behavior in other domains of planning, such as approaching the extended network of the counterpart to enquire about interests or offering to socialize before bargaining begins.

Heuristic search patterns were evident across Study 1a, 1b, and 1c. Without constraints in a complex task, negotiators investigate the search space equally (Study 1a) and engage in a pattern consistent with reading. But when constraints are imposed (Study 1b), negotiators want to know something about each category of information. When the task is simple such that they could examine most of the search space (Study 1c), they behave in a similar manner to a complex task without constraints. Negotiators appear to rely on heuristic patterns when they can afford to do so.

4.2 Implications for Theory

Our research offers first insights into how people search and evaluate information as they plan to negotiate. We outline three major observations that will facilitate negotiation theory about planning.

First, personality and gender can predict the kind of information negotiators deem as important. Where the planning task requires evaluation among known options, personality and gender appear to predict preferences (Study 2). When the task is effortful, complex, and no constraints are present, agreeableness predicted greater persistence (Study 1a), but not when constraints were present (Studies 1b and 1c). Thus, both task type and task complexity appear to be a factor in how individual differences predict behavioral patterns. This leads to the conclusion that researchers should aim to theorize about both individual differences and situational factors that contribute to behavior, consistent with the interactionist perspective (Terborg 1981). That perspective posits that both individual and situational factors are required to understand performance, as neither can provide a sufficient account on its own (Caldwell and O’Reilly 1990). This means that null associations between personality and search behavior, as observed in Study 1c, can still be informative, as they provide information about the amount of situational constraint necessary to suppress the expression of individual differences. Across the studies reported, we demonstrate that personality can play a smaller or a larger role in shaping planning behavior.

Second, we observed few gender differences across the studies. The lack of gender differences in information search suggests that the origin of disparities in negotiation outcomes (Mazei et al. 2015) is not likely to be a product of differences in planning efforts. Rather, such disparities are likely the cause of feelings, cognitions, and behaviors revealed during bargaining.

Third, the search process can be subject to complexity and constraint. We observed negotiators to search following common reading pattern in Studies 1a and 1c, when all or most of the matrix could be examined. In Study 1b, participants selectively targeted information when much of the matrix could not be examined. Negotiators engaged in targeted search when all information could not be examined. But when they can, many ‘start from the top’.

5 Limitations and Future Research

We note multiple avenues for future research. First, we consider factors related to the limitations of the studies, then take a step back to consider other possibilities not addressed in this paper.

The search process modeled by the Mouselab paradigm is highly stylized. It presumes that all options are knowable and that search comprises searching easily accessible options. But in the field, negotiators likely will need to define relevant attributes before engaging search. For example, information search may start with an internet search, but one must know or decide upon the relevant keywords to start with. Information search can also be an interactive process, which involves people approaching others, such as requesting an interview with a former employee of a target company, rather than purchasing or searching for information in a digital format. Search is more than inspecting a matrix, and much future research awaits to fully explore the topic of how negotiators search for information.

We also note that individual differences generally did not predict the choice of information. Although few significant bivariate relationships and post hoc mediations were observed, the Big Five and gender rarely predicted what information people ultimately chose. Moreover, when some significant relationships were observed, they were counterintuitive. Future research could replicate and extend these observations to achieve a better understanding of such relationships. We next consider factors not examined in the current research.

Planning can be conducted alone, but it can also be the result of an interactive process. Negotiation can arise from disputes, necessitating discussion about the limits of the issues to be discussed before bargaining occurs (Gulliver 1979; Williams 1985), or the process may involve intra-organizational bargaining before the focal negotiation (Walton and McKersie 1965). Moreover, some creative planning can involve extensive social interaction. For example, negotiators for Kennecott Copper faced the nationalization of their Chilean copper mine. Their planning involved contacting prospective buyers for ore, seeking guarantors for loans and having them subject to a foreign power, and selling collection rights to banks in a different set of countries (Lax and Sebenius 2006). Such aspects of planning deserve greater research focus.

There are greater complexities to explore even when search involves non-interactive information gathering. This is because complex negotiations require consideration of many kinds of information, and their value is not always apparent, nor obviously linked to valued outcomes. For example, since many people assume that negotiation is a zero-sum situation (Thompson and Hastie 1990), information about counterpart interests could be overlooked. Likewise, information about counterpart limits may be less important than initially appears if there is integrative potential that allows both sides to benefit. Insight into what people find relevant and what they attempt to use to further their goals is an avenue for better understanding how negotiators think about and act in the planning phase.

Individual differences beyond the Big Five and gender could influence cognition and behavior in planning. For example, greater experience can inform planning with expert negotiators engaging in planning differently from novices, as can cross-cultural differences, known to result in divergent patterns of bargaining (Adair and Brett 2005). Other factors may include organizational policies and norms that also influence how negotiators approach the planning phase. Examining such factors, either on their own or in concert with individual differences studied here should furnish the literature with greater insights into the complexity of the negotiation process.

The observations on personality and gender imply individual differences can have a considerable influence on the negotiation process. Dynamic phase models imply that bargaining is influenced by how negotiators plan, with the definition and limits to issues being key determinants of how people narrow their differences through bargaining (Gulliver 1979). Because individual differences can shape what is important to consider, they have the potential to shape what and how people choose to bargain, and this can influence agreements and relationships that form as a result. Future research can examine downstream impacts that follow from the patterns of planning observed in the current investigation.

Finally, evaluating and searching for information are only a part of planning. As Peterson and Lucas (2001) pointed out, information evaluation and search is only a part of intelligence gathering. There are other aspects of planning, including formulating bargaining objectives, developing a strategy, as well as rehearsing for the bargaining phase. Those aspects of planning await empirical exploration.

Data Availability

The data and analyses files are available online at [https://osf.io/qepnz/?view_only=6219c15d71146d4a77183ef9005d9b7]. The hypotheses are not pre-registered.

Notes

We note that information search can also occur in the bargaining phase, as in the case of negotiators searching for the information about counterpart preferences (e.g., Polzer and Neale 1995).

References

Adair WL, Brett JM (2005) The negotiation dance: Time, culture, and behavioral sequences in negotiation. Organ Sci 16:33–51. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0102

Alexander JF, Schul PL, McCorkle DE (1994) An assessment of selected relationships in a model of the industrial marketing negotiation process. J Pers Sell Sales Manage 14:25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.1994.10753991

Amanatullah ET, Morris MW (2010) Negotiating gender roles: Gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. J Pers Soc Psychol 98:256–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017094

Amanatullah ET, Morris MW, Curhan JR (2008) Negotiators who give too much: unmitigated communion, relational anxieties, and economic costs in distributive and integrative bargaining. J Pers Soc Psychol 95:723–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012612

American Bar Association (2009) American Bar Association guide to resolving legal disputes: inside and outside the courtroom. Random House Reference

Aronoff J, Wilson JP (2014) Personality in the social process. Psychology Press

Barrick MR, Mount MK (1991) The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta-analysis. Pers Psychol 44:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

Barrick MR, Stewart GL, Piotrowski M (2002) Personality and job performance: Test of the mediating effects of motivation among sales representatives. J Appl Psychol 87:43–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.43

Barron LA (2003) Ask and you shall Receive? Gender differences in negotiators’ beliefs about requests for a higher salary. Hum Relat 56:635–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267030566001

Barry B, Friedman RA (1998) Bargainer characteristics in distributive and integrative negotiation. J Pers Soc Psychol 74:345–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.345

Bieleke M, Dohmen D, Gollwitzer PM (2020) Effects of social value orientation (SVO) and decision mode on controlled information acquisition—A Mouselab perspective. J Exp Soc Psychol 86:103896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103896

Boothby EJ, Cooney G, Schweitzer ME (2022) Embracing complexity: a review of negotiation research. Ann Rev Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-033020-014116

Borghans L, Duckworth A, Heckman JJ, Ter Weel B (2008) The economics and psychology of personality traits. J Hum Resour 43:972–1059. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.43.4.972

Bowles HR, Babcock L, McGinn KL (2005) Constraints and triggers: situational mechanics of gender in negotiation. J Pers Soc Psychol 89:951–965. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.951

Brown S, O’Donnell E (2011) Proactive personality and goal orientation: a model of directed effort. J Organ Cult Commun Confl 15:103–119

Cable DM, Judge TA (2003) Managers’ upward influence tactic strategies: the role of manager personality and supervisor leadership style. J Organ Behav 24:197–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.183

Caldwell DF, O’Reilly CA (1990) Measuring person-job fit with a profile-comparison process. J Appl Psychol 75:648–657. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.6.648

Carnevale PJ, De Dreu CKW (2006) Motive: the negotiator’s raison d’eˆtre. Frontiers of social psychology: negotiation theory and research. Psychology Press, pp 55–76

Chaiken S, Ledgerwood A (2012) A theory of heuristic and systematic information processing. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET (eds) Handbook of theories of social psychology. Sage Publications Ltd, pp 246–266

Chamorro-Premuzic T, Furnham A (2005) Personality and intellectual competence. Taylor and Francis Group

Chen F, Fischbacher U (2016) Response time and click position: cheap indicators of preferences. J Econ Sci Assoc 2:109–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-016-0026-6

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. L. Erlbaum Associates

Costa PT, McCrae RR (1992a) Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEP five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources

Costa PT, McCrae RR (1992b) Four ways five factors are basic. Personal Individ Differ 13:653–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I

De Dreu CKW, Van Lange PAM (1995) The impact of social value orientations on negotiator cognition and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 21:1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672952111006

Denis DJ (2019) SPSS data analysis for univariate, bivariate, and multivariate statistics. John Wiley Inc

DeRue DS, Conlon DE, Moon H, Willaby HW (2009) When is straightforwardness a liability in negotiations? The role of integrative potential and structural power. J Appl Psychol 94:1032–1047. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014965

Dimotakis N, Conlon DE, Ilies R (2012) The mind and heart (literally) of the negotiator: personality and contextual determinants of experiential reactions and economic outcomes in negotiation. J Appl Psychol 97:183–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025706

Eagly AH, Wood W (2012) Social role theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology. Sage Publications Ltd, pp 458–476

Eisenkraft N, Elfenbein HA (2010) The way you make me feel: evidence for individual differences in affective presence. Psychol Sci 21:505–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610364117

Elfenbein HA (2015) Individual differences in negotiation: a nearly abandoned pursuit revived. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 24:131–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414558114

Feist GJ (1998) A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2:290–309. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0204_5

Fleeson W (2004) Moving personality beyond the person-situation debate. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 13:83–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00280.x

Galinsky AD, Mussweiler T (2001) First offers as anchors: The role of perspective-taking and negotiator focus. J Pers Soc Psychol 81:657–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.657

Glass JC, Kilpatrick BB (1998) Financial planning for retirement: An imperative for baby boomer women. Educ Gerontol 24:595–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/0360127980240606

Goldstein WM, Einhorn HJ (1987) Expression theory and the preference reversal phenomena. Psychol Rev 94:236–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.2.236

Graziano WG, Jensen-Campbell LA, Hair EC (1996) Perceiving interpersonal conflict and reacting to it: the case for agreeableness. J Pers Soc Psychol 70:820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.820

Greenhalgh L (2001) The Biopharm-Seltek negotiation

Gulliver PH (1979) Disputes and negotiations: a cross-cultural perspective. Academic Press

Hayes-Roth B, Hayes-Roth F (1979) A cognitive model of planning. Cognit Sci. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0304_1

Jacobs-Lawson JM, Hershey DA, Neukam KA (2004) Gender differences in factors that influence time spent planning for retirement. J Women Aging 16:55–69. https://doi.org/10.1300/J074v16n03_05

Jang D, Elfenbein HA, Bottom WP (2018) More than a phase: Form and features of a general theory of negotiation. Acad Manag Ann 12:318–356. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0053

John OP, Srivastava S (1999) The big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: theory and research. Guilford Press, pp 102–138

Johnson EJ, Payne JW, Bettman JR, Schkade DA (1989) Monitoring information processing and decisions: the mouselab system. DTIC Document

Kennan GF, Mearsheimer JJ (2012) American diplomacy, 60th-anniversary expanded. University of Chicago Press

Krasman J (2010) The feedback-seeking personality: big five and feedback-seeking behavior. J Leadersh Organ Stud 17:18–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051809350895

Kulik CT, Olekalns M (2012) Negotiating the gender divide: lessons from the negotiation and organizational behavior literatures. J Manag 38:1387–1415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311431307

Lax DA, Sebenius JK (2006) 3-D negotiation: Powerful tools to change the game in your most important deals. Harvard Business Press

Letkiewicz JC, Fox JJ (2014) Conscientiousness, financial literacy, and asset accumulation of young adults. J Consum Aff 48:274–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12040

Li M, Peng H, Ji L (2020) Roles of cognitive load and self-relevance during emotional information searching on decision-making. J Behav Dec Mak 33:463–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2169

Ma Z, Jaeger A (2005) Getting to yes in China: Exploring personality effects in Chinese negotiation styles. Group Decis Negot 14:415–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-005-1403-3

Mazei J, Hüffmeier J, Freund PA et al (2015) A meta-analysis on gender differences in negotiation outcomes and their moderators. Psychol Bull 141:85–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038184

McCrae RR, John OP (1992) An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J Pers 60:175–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x

Messick DM, McClintock CG (1968) Motivational bases of choice in experimental games. J Exp Soc Psychol 4:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(68)90046-2

Meyer RD, Dalal RS (2009) Situational strength as a means of conceptualizing context. Ind Organ Psychol 2:99–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.01114.x

Meyer RD, Dalal RS, Hermida R (2010) A review and synthesis of situational strength in the organizational sciences. J Manag 36:121–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.01114.x

Mischel W, Shoda Y (1995) A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol Rev 102:246–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.246

Molloy GJ, O’Carroll RE, Ferguson E (2014) Conscientiousness and medication adherence: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med 47:92–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9524-4

Paunonen SV (1998) Hierarchical organization of personality and prediction of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 74:538–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.538

Paunonen SV, Haddock G, Forsterling F, Keinonen M (2003) Broad versus narrow personality measures and the prediction of behaviour across cultures. Eur J Pers 17:413–433. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.496

Payne JW (1976) Task complexity and contingent processing in decision making: an information search and protocol analysis. Organ Behav Hum Perform 16:366–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90022-2

Peterson RM, Lucas GH (2001) Expanding the antecedent component of the traditional business negotiation model: Pre-negotiation literature review and planning-preparation propositions. J Mark Theory Pract 9:37–49

Polzer JT, Neale MA (1995) Constraints or catalysts? Reexamining goal setting with the context of negotiation. Hum Perform 8:3–26. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup0801_2

Pruitt DG (2012) A history of social conflict and negotiation research. Handbook of the history of social psychology. Psychology Press, pp 431–452

Robbins SP, Judge T, Millett B, Boyle M (2017) Organisational behaviour, 8th edn. Pearson Australia, Melbourne

Roloff ME, Putnam LL, Anastasiou L (2003) Negotiation skills. Handbook of communication and social interaction skills. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp 801–833

Schkade DA, Johnson EJ (1989) Cognitive processes in preference reversals. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 44:203–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(89)90025-3

Schneider AK, Honeyman C (2006) The negotiator’s fieldbook. American Bar Association

Schulte-Mecklenbeck M, Johnson JG, Böckenholt U et al (2017) Process-tracing methods in decision making: on growing up in the 70s. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 26:442–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417708229

Selig JP, Preacher KJ (2008) Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: an interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects

Sharma S, Bottom WP, Elfenbein HA (2013) On the role of personality, cognitive ability, and emotional intelligence in predicting negotiation outcomes: a meta-analysis. Organ Psychol Rev 3:293–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386613505857

Soto CJ, John OP (2017) Short and extra-short forms of the big five inventory–2: the BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. J Res Pers 68:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.02.004

Stuhlmacher AF, Adair CK (2011) Personality and negotiation. Negotiation excellence - successful deal making, Michael Benoliel. World Scientific Publishing, pp 195–210

Stuhlmacher AF, Linnabery E (2013) Gender and negotiation: a social role analysis. In: Olekalns M, Adair W (eds) Handbook of research on negotiation research, Edward Elgar, pp 221–248

Terborg JR (1981) Interactional psychology and research on human behavior in organizations. AMR 6:569–576. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1981.4285691

Tett RP, Burnett DD (2003) A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J Appl Psychol 88:500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500

Thompson L (1990) Negotiation behavior and outcomes: Empirical evidence and theoretical issues. Psychol Bull 108:515–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.515

Thompson LL, Hastie R (1990) Social perception in negotiation. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 47:98–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(90)90048-E

Trapnell PD, Paulhus DL (2012) Agentic and communal values: their scope and measurement. J Pers Assess 94:39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.627968

Walters AE, Stuhlmacher AF, Meyer LL (1998) Gender and negotiator competitiveness: a meta-analysis. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 76:1–29. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2797

Walton RE, McKersie RB (1965) A behavioral theory of labor negotiations: an analysis of a social interaction system. McGraw-Hill

White JB, Tynan R, Galinsky AD, Thompson L (2004) Face threat sensitivity in negotiation: roadblock to agreement and joint gain. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 94:102–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.03.005

Willemsen MC, Johnson EJ (2011) Visiting the decision factory: observing cognition with MouselabWEB and other information acquisition methods. In: Schulte-Mecklenbeck M, Kühberger A, Ranyard R (eds) A handbook of process tracing methods for decision research: a critical review and user’s guide, Psychology Press, pp 21–42

Willemsen MC, Johnson EJ (2008) MouselabWEB

Williams GR (1985) A lawyer’s handbook for effective negotiation and settlement. Washington State Bar Association

Yang L, Toubia O, De Jong MG (2015) A bounded rationality model of information search and choice in preference measurement. J Mark Res 52:166–183. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.13.0288

Zartman IW (2006) Process and stages. In: Schneider AK, Honeyman C (eds) The negotiator’s fieldbook: the desk reference for the experienced negotiator. American Bar Association, pp 95–98

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Simon Restubog and Sudeep Sharma for their constructive comments on this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DL and DJ designed, collected data, analyzed data, and wrote the report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Research involving Human Participants with ethical approval (#2020001481) by the University of Queensland, Australia.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Le, D.Q., Jang, D. Individual Differences and Situational Constraint Predict Information Search in Negotiation Planning. Group Decis Negot 32, 667–699 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-023-09824-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-023-09824-2