Abstract

Although both employee wellbeing and performance are valued by organizations, achieving them conjointly is not simple in practice. Prior studies have highlighted the role of daily experiences of recovery from work stress for employee wellbeing and performance. In a work-life characterized by pressures to intensify the pace of work, employees may increasingly use proactive efforts to shape their daily off-job time to effectively recover from stress and maintain their wellbeing and performance. Based on the integrative needs model of crafting, effort-recovery model, and conservation of resources theory as guiding frameworks, we examine whether employees’ daily proactive recovery strategies predict daily off-job and work stress, affect, and subjective work performance through enhanced recovery experiences. Daily diary measurements were collected among a sample of 377 Norwegian employees across a period of two weeks in early 2022 (from Monday to Thursday, i.e., eight measurement days in total). Results of Bayesian multilevel models showed that crafting for detachment, for relaxation, and for autonomy during off-job time negatively predicted off-job stress and negative affect through matching recovery experiences, whereas crafting for mastery positively predicted positive affect through mastery experiences. Crafting for relaxation and for autonomy were directly negatively related to next-day work stress, but these effects were not mediated by matching recovery experiences. Crafting for autonomy positively predicted next-day self-rated work performance through control experiences. Our study contributes to the literature on recovery from work by highlighting proactive recovery strategies as important initiators of daily recovery processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although both employee wellbeing and performance are key foci in today’s organizations, achieving both conjointly (i.e., the “happy worker-productive worker” thesis) is not so simple in practice (Wright & Cropanzano, 2000). For example, organizational efforts to enhance work performance are related to heightened perceptions of stress in employees, with potential negative consequences for their wellbeing (Jensen et al., 2013; Topcic et al., 2016). The rapidly changing world of work, and in particular work intensification, poses further challenges for employees to keep and protect their wellbeing both on and off the job (Mauno & Kinnunen, 2021). One such protective factor is off-job recovery from work, defined as a process of reducing and eliminating physical and psychological strain caused by work (Demerouti et al., 2009; Zijlstra & Sonnentag, 2006).

Studies on psychological recovery have primarily focused on recovery experiences, where four distinct experiences are identified: detachment from work (i.e., experiencing a mental disconnection from work-related thoughts during off-job time), relaxation (i.e., a state of psychobiological unwinding from stress), control (i.e., a perception that one is in charge of one’s off-job activities), and mastery (i.e., having a sense of challenge and proficiency; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). These recovery experiences have been shown to relate positively to occupational health and wellbeing by reducing stress and negative affect, and improving positive affect, as well as work performance, both in general and at the daily level (Headrick et al., 2023; Steed et al., 2021).

As shown in prior research, daily attainment of recovery experiences can result from an interplay between various individual, work- and off-job related traits and characteristics such as personality, job demands, and family situation (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007), and from non-proactive behaviors such as habits (Sonnentag & Jelden, 2009). However, less is known about the role of distinct strategies employees may use to proactively and intentionally initiate and self-manage recovery experiences in their everyday nonwork lives (de Bloom et al., 2020). As such, it is currently unclear whether and to what extent employees can enhance their recovery and reduce strain through proactive efforts in daily off-job time, as has been suggested in recent recovery literature (Heydarifard & Krasikova, 2023; Karabinski et al., 2021; Virtanen et al., 2021).

In the work domain, several studies have shown that employees do proactively shape their work tasks and roles to enhance their daily engagement and vitality, and to reduce daily fatigue (e.g., proactive vitality management; Op den Kamp et al., 2018; strengths use; Bakker et al., 2019; job crafting; Bakker and Vries, 2021; Hur & Shin, 2023). Moreover, such proactive strategies at work have been shown to reduce the risk of burnout, an outcome of a sustained lack of recovery (Hakanen et al., 2017; Tims et al., 2013). However, research on proactive strategies used in the off-job domain is much scarcer (de Bloom et al., 2020; Tims et al., 2022), with no studies so far focusing on proactive off-job strategies in relation to daily recovery processes.

The lack of focus on employees’ proactive strategies for recovery is problematic for three reasons. First, in an intensifying work-life characterized by pressures to intensify the pace of work (e.g., to work harder and faster; Mauno & Kinnunen, 2021), employees may be increasingly required to engage in proactive efforts to shape their daily off-job time in order to effectively manage stress. As such, daily proactive recovery strategies may be a highly effective way for employees to maintain their own daily wellbeing and performance in challenging, stressful circumstances, highlighting the need to examine proactive strategies employees use for their recovery in addition to mental states and experiences associated with a sufficient recovery. Second, as employee recovery from work occurs during off-job time (e.g., leisure, house- and childcare), the off-job domain forms the primary and most proximal context to examine whether employees can and do proactively protect themselves against wellbeing- and performance-detriments associated with work stress. As such, a sole focus in previous research on the role of proactive strategies used at work (e.g., job crafting) for stress-related outcomes gives an incomplete picture of the role of proactivity for daily recovery processes. Third, directly focusing on individuals’ proactive strategies for recovery is also important for informing and advancing the development of recovery interventions, which often encourage participants to make changes in their daily off-job time to improve recovery (Karabinski et al., 2021; Smit & Barber, 2016).

The current study makes two key contributions to the recovery from work literature. First, with the integrative needs model of crafting, effort-recovery model and conservation of resources theory as guiding theoretical frameworks, we examine proactive off-job recovery strategies at the day-level for the first time, extending earlier daily diary studies (e.g., Hur & Shin, 2023; Op den Kamp et al., 2018) which have investigated the role of proactive work-domain strategies for recovery processes. With this focus on employee proactivity in the off-job domain, we provide a novel bottom-up perspective on how employees may proactively achieve recovery from work stress in “life as it is lived” off the job (Bolger et al., 2003). As such, we extend prior recovery research by highlighting that employees are not only passive recipients of their circumstances during off-job time, but also engage in proactive strategies to shape and self-initiate their recovery experiences. Second, we assess the role of employees’ proactive recovery strategies for both daily happiness and productivity (Wright & Cropanzano, 2000), testing whether use of proactive recovery strategies is related to higher wellbeing (i.e., lower off-job and work stress, higher positive and lower negative affect), and higher self-rated work performance through recovery experiences. With these foci, we provide a more complete picture of the off-job recovery process at the day-level than do prior studies, starting from the daily use of proactive recovery strategies, followed by daily recovery experiences and wellbeing, and finally lagged effects on stress and performance on the following workday. Our findings provide novel insights for the further development of recovery interventions, which could specifically focus on proactive strategies to initiate behavioral change for recovery that may in turn promote both employee wellbeing and performance.

Off-Job Crafting as a Proactive Strategy for Employee Recovery from Work

While still limited in scope, recent research has started to examine employees’ crafting efforts—proactive and self-initiated strategies to shape themselves and their environment in order to better align with psychological needs—in the context of off-job life (de Bloom et al., 2020). These crafting efforts can be aimed at reducing or avoiding negative outcomes (i.e., avoidance-focused crafting) or targeted at approaching desirable outcomes (i.e., approach-focused crafting; de Bloom et al., 2020). More specifically, employees’ off-job crafting efforts have been conceptualized as proactive and self-initiated changes targeted at enhancing experiences of detachment, relaxation, autonomy, mastery, meaning, and affiliation (Kujanpää et al., 2022). As such, off-job crafting is individuals’ proactive strategy for recovery attainment, distinguishing it from other key concepts examined within the field of recovery from work such as recovery experiences and leisure activities (Kujanpää et al., 2022; Sonnentag et al., 2017). In particular, proactive recovery strategies are self-initiated, intentional, deliberate, and self-targeted behavioral and cognitive efforts focused at shaping one’s off-job time (Kujanpää et al., 2022). These features distinguish the concept of proactive recovery strategies from the more researched concepts of recovery experiences and leisure activities. Indeed, recovery experiences and leisure activities are leisure-domain mental states or behaviors that often occur habitually or non-deliberately, and as such do not necessarily involve such proactive efforts (de Bloom et al., 2020; Iso-Ahola, 2015). Another distinctive aspect of proactive recovery strategies is that they tend to take some effort to initiate, in comparison to recovery experiences which immediately provide rather than expend energy (see also Bakker & Oerlemans, 2019; Berg et al., 2010). Kujanpää et al. (2022) investigated whether proactive recovery strategies can be distinguished from both recovery experiences (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007) and leisure activities (e.g., resting, creative activities). An average variance extracted (AVE) analysis revealed that all AVE estimates of proactive recovery strategies were higher than their shared variance with recovery experiences, demonstrating discriminant validity. Moreover, leisure activities showed only small factor loadings below 0.30 to corresponding proactive recovery strategies (e.g., creative activities loading to crafting for mastery; Kujanpää et al., 2022). Furthermore, the concept of proactive recovery strategies differs from boundary management tactics and boundary enactment (e.g., Kreiner et al., 2009; Wepfer et al., 2018) in that proactive recovery strategies are not targeted towards shaping boundaries between work and home, but rather involve proactive changes within off-job domain aimed to foster recovery regardless of one’s work-home boundary segmentation or integration preferences. In addition, proactive recovery strategies involve life domains such as leisure and volunteering that have not been so far theorized in terms of boundary management tactics.

According to the integrative needs model of crafting (de Bloom et al., 2020), employees engage in off-job crafting efforts in order to satisfy their psychological needs. For instance, an employee could craft for detachment by actively scheduling some “me-time” each day to forget stressful work duties, or craft for mastery by taking on a language course with the aim of developing their skills and competences. In a qualitative study illustrating these different strategies, 97 US employees were asked to provide examples of their prior off-job crafting efforts (Kujanpää et al., 2022). Findings showed that employees use a wide variety of activities for each off-job crafting strategy. For instance, to name just a few activities used in crafting for detachment, engaging in hobbies, physical exercise, reading, listening to music, socializing with friends, ignoring e-mails, and household activities were mentioned. This indicates that differentiating proactive strategies in the off-job domain by the target of crafting efforts (i.e., individual needs) rather than by specific off-job activities provides a more parsimonious and systematic framework (Kujanpää et al., 2022; see also Daniels, 2012). When successful, employees’ crafting efforts are expected to lead to matching needs’ fulfillment (e.g., crafting for mastery would enhance mastery), which in turn is posited to lead to positive effects for wellbeing and performance across life domains (de Bloom et al., 2020). In this study, we examine off-job crafting efforts as proactive recovery strategies matching with and in relation to the four recovery experiences posited by Sonnentag and Fritz (2007), as these experiences are primary predictors of wellbeing-outcomes as compared to meaning and affiliation (Kujanpää et al., 2020).

Empirical studies on off-job crafting have shown that employees’ off-job crafting efforts are positively related to general wellbeing (e.g., life satisfaction, sense of coherence) and family role performance (Brauchli et al., 2023; Kujanpää et al., 2022; Tušl et al., 2022). Regarding antecedents, need strength was found to predict further off-job crafting efforts, whereas focus on future opportunities predicted crafting for mastery but not crafting for detachment, for relaxation, or for autonomy (Kosenkranius et al., 2021). Moreover, off-job crafting can have spillover effects to subjective workability, job satisfaction, and lower burnout complaints, whereas the effects on work engagement have been weaker (Brauchli et al., 2023; Kujanpää et al., 2022; Pijpker et al., 2022). However, work stress and performance have not been previously examined as outcomes of off-job crafting, making it unclear whether crafting in the off-job domain can influence work stress and performance as has been demonstrated for job crafting (Rudolph et al., 2017; Sakuraya et al., 2016). Based on the matching perspective of the integrative needs model of crafting, which suggests that proactive recovery strategies produce enhancements in wellbeing through matching recovery experiences (de Bloom et al., 2020), we expect that daily proactive recovery strategies can initiate a daily recovery process by promoting matching daily recovery experiences. Insofar as crafting for a specific experience (e.g., for relaxation) is successful in promoting that experience, this can be expected to lead to optimal functioning (i.e., wellbeing and performance) across life domains. However, these posited mediational paths have not so far been empirically tested, with research on off-job crafting focusing so far either on direct effects of proactive recovery strategies (Kujanpää et al., 2022; Pijpker et al., 2022) or on antecedents (Kosenkranius et al., 2021).

In a prior longitudinal study, proactive recovery strategies were also shown to directly predict recovery experiences over a period of three months (Kujanpää et al., 2022). That is, off-job crafting predicted matching recovery experiences while controlling for the baseline in recovery experiences, with the one exception of crafting for detachment which was not significantly related to detachment over time. One possible explanation for this result is that crafting for detachment may be difficult to sustain over a long period of time. Indeed, time pressures and unfinished tasks might force employees to eventually think about their work during off-job time (Syrek & Antoni, 2014), further highlighting the need to investigate this relation at the day-level. In the only day-level study conducted so far on this topic, daily needs-based crafting examined as a composite score of the six dimensions (i.e., crafting for detachment, relaxation, autonomy, mastery, meaning, and affiliation) contributed positively to daily energy levels of a sample of 110 employees (Kosenkranius et al., 2023). Crafting increased towards the evening, suggesting that evenings provide employees with important opportunities for engaging in crafting. However, as job and off-job crafting were not separated in this study, it is not clear to what extent the positive effects for energy can be attributed to off-job crafting, specifically. Moreover, the within-person reliability of the composite crafting measure was low, indicating potentially distinct processes for the different crafting sub-dimensions (Kosenkranius et al., 2023). In this paper, we highlight two such conceptually distinct processes, namely daily avoidance- and approach-focused proactive recovery strategies, and for the first time examine the potentially distinct effects of employees’ proactive shaping of their off-job time with an avoidance- and an approach-focus.

Avoidance-Focused Proactive Recovery Strategies: Protecting Daily Wellbeing and Performance Through Proactively Maintaining Homeostatic Balance

Proactive recovery strategies can be further divided into two key categories that differ based on their motivational focus: avoidance-focused strategies and approach-focused strategies (de Bloom et al., 2020; see also Bruning & Campion, 2018; Zhang & Parker, 2019 on approach- and avoidance job crafting). Based on the integrative needs model of crafting, crafting for detachment and for relaxation can be conceptualized as avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies, initiating a “passive recovery” process wherein employees strive to get a relief from the stress and its negative effects (de Bloom et al., 2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Trougakos, 2014). Such an avoidance-focused process draws theoretically from the effort-recovery model: if sufficient recovery from stress after the workday is not achieved, this results in increasing load reactions that threaten to impair employee wellbeing (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). As such, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies are self-initiated efforts focused at reducing strain and keeping a homeostatic balance of the body and the mind.

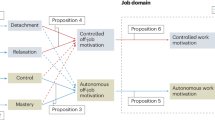

Drawing from the effort-recovery model, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies could enable employees to proactively decrease their mental load and prevent resource drain through experienced detachment and relaxation (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). As such, crafting for detachment and for relaxation can allow individuals to become intentionally disengaged and released from daily stressors. This way, negative activation after the working day may be actively halted, allowing recovery from stress to take place (see also Daniels, 2012; Meijman & Mulder, 1998). Avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies may also further reduce stress on the following workday, as stress-related load reactions and spillover of negative activation and tension could be prevented (Quinn et al., 2012). Thus, through avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies, employees may actively protect their daily life from stressful thoughts and obligations. In line with these perspectives, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies have been found to be negatively related to burnout complaints, an indicator of prolonged work stress (Otto et al., 2020; Pijpker et al., 2022). Thus, we propose (Fig. 1):

-

H1: Daily off-job crafting for detachment and for relaxation are negatively related to (a) daily off-job stress and (b) next-day work stress through matching recovery experiences (daily detachment and relaxation)

Crafting for detachment and for relaxation may also have the potential for diminishing negative emotions and creating opportunities for positive emotions. Firstly, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies could help employees to intentionally lower their mental tension and negative activation after the working day, such as by making time in the evening to engage in a preferred activity for relaxation. This self-management of perceived pressures is likely to aid employees to stabilize emotions such as anxiety or irritability after a stressful workday, diminishing negative affect (see also Sonnentag et al., 2008; Sonnentag & Niessen, 2020). Secondly, actively focusing on potentially detaching and relaxing activities may create important opportunities for experiencing pleasant emotions such as enjoyment and contentment. Avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies may also help employees to actively participate in positively engaging off-job activities with a full, mindful attention (Heydarifard & Krasikova, 2023). As such, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies could have an emotionally restorative function, enhancing daily affective wellbeing through detachment and relaxation experiences (see also Syrek et al., 2018). Studies in leisure sciences have shown findings that support these notions, indicating that individuals across various cultures support their positive emotions by intentionally creating leisure spaces that provide opportunities for rest, relaxation, and detachment from external pressures (Iwasaki, 2007, 2017). As such, we propose:

-

H2: Daily off-job crafting for detachment and for relaxation are (a) negatively related to daily negative affect and (b) positively related to daily positive affect through matching recovery experiences (daily detachment and relaxation)

The benefits of daily proactive recovery strategies may not be limited to wellbeing, but could also spill over to influence daily work performance. In line with the integrative needs model of crafting, crafting efforts could produce positive spillover in performance outcomes across life domains, a key mediator being recovery experiences (e.g., relaxation) that match the type of used efforts (de Bloom et al., 2020). Through avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies, employees may proactively restore the energy that is depleted during the workday, enabling them to start the next workday more alert and focused (see also Bakker, 2017; Meijman & Mulder, 1998). As posited by the effort-recovery model, the ability to expend effort throughout the workday and the willingness to do so intently are two key conditions for employees’ effort investment in work performance episodes (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). A proactive restoration of one’s energy during off-job time through detachment and relaxation gained by engaging in avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies could allow employees to keep their energy levels high throughout the next workday, being thus able to expend further effort when work performance episodes demand so (see also Kosenkranius et al., 2023). Moreover, employees that engage in avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies during daily off-job time may be more willing to invest their effort in work tasks on the following workday, as they readily have off-job strategies in place to counter the mental strain and need for recovery that can emerge from continued work effort investment (Sonnentag & Zijlstra, 2006). Thus, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies could, through detachment and relaxation, create more optimal energetic conditions for performance episodes during the next workday. As such, we propose:

-

H3: Daily off-job crafting for detachment and for relaxation are positively related to next-day self-rated performance through matching recovery experiences (daily detachment and relaxation)

Approach-Focused Proactive Recovery Strategies: Promoting Daily Wellbeing and Performance Through Self-Initiated Creation of New Resources

Based on the integrative needs model of crafting (de Bloom et al., 2020), crafting for autonomy and for mastery can be conceptualized as approach-focused proactive recovery strategies, relating to an “active recovery” process through which employees can initiate creation of new personal resources (de Bloom et al., 2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Trougakos, 2014). In line with the conservation of resources theory, personal resources such as autonomy/control and mastery positively energize employees and tend to lead to other resources by clustering together, forming resource cycles (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Approach-focused proactive recovery strategies are self-initiated efforts that can create opportunities for such resource accumulation, as the individual shapes their off-job time to enhance their sense of autonomy and mastery (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll, 2011).

When resources such as control and mastery experiences are gained through approach-focused proactive recovery strategies, they may be further invested to prevent resource loss (Westman et al., 2004). This way, experiences of stress, both at work and in the off-job domain, can be actively managed, potentially decreasing their strength and frequency in daily life (Iwasaki & Mannell, 2000; Petrou & Bakker, 2016). For instance, by pursuing positively challenging activities through crafting for mastery, an employee may convert the experience of being tense and stressed out to a sense of positive and meaningful activation (see also Schwarzer, 2001). Approach-focused proactive recovery strategies could also decrease stress by reducing the anticipation of and rumination about future stress, as the employee focuses on actively enriching their off-job time instead of worrying about the negative aspects of their work. As such, approach-focused proactive recovery strategies may help employees to reduce their experiences of off-job and work stress through control and mastery experiences. Thus, we propose:

-

H4: Daily off-job crafting for autonomy and for mastery are negatively related to (a) daily off-job stress and (b) next-day work stress through matching recovery experiences (daily control and mastery)

Approach-focused proactive recovery strategies may also help employees to enhance their affective wellbeing. Firstly, approach-focused proactive recovery strategies may help employees to gain new resources that directly counteract the detriments for affective wellbeing caused by stressful work. For instance, crafting for autonomy and for mastery by taking on new personally interesting and challenging volunteering activities could help employees to compensate for a stressful or uninteresting workday, decreasing daily negative affect (Stebbins, 2015). Similar results have been found in studies within the leisure domain, wherein leisure crafting conceptualized as a single-dimensional proactive pursuit of leisure activities focused on goal setting, human connection, learning, and personal development was negatively associated with emotional exhaustion (Abdel Hadi et al., 2021; Chen, 2023). Furthermore, approach-focused proactive recovery strategies may bring positive emotions as the individuals shape their off-job time to include personally interesting and challenging off-job activities in their daily schedules. In this self-initiated process, in line with the conservation of resources theory, control and mastery experiences gained through approach-focused proactive recovery strategies may be converted to positive emotions such as joy and delight, enhancing positive affect through resource accumulation (Hobfoll et al., 2018). As such, we propose:

-

H5: Daily off-job crafting for autonomy and for mastery are (a) negatively related daily negative affect and (b) positively related to daily positive affect through matching recovery experiences (daily control and mastery)

Furthermore, in line with conservation of resources theory, control and mastery experiences provide employees with resources (e.g., feelings of autonomy and personal accomplishment), that can be further invested in performance episodes in the work domain (Kelly et al., 2020; Quinn et al., 2012; Vogel et al., 2016). Such resource accumulation has the potential to form resource cycles, providing increased energy, creativity, and proactivity that can be utilized for performing more effectively in work tasks on the following day (Chawla et al., 2020; Ouyang et al., 2019). For instance, approach-focused proactive recovery strategies are likely to provide additional regulatory resources for employees, enhancing their capacity to efficiently exert effort and regulate attention in tasks throughout the next workday and thus improving work performance (Beal et al., 2005). As such, approach-focused proactive recovery strategies could create a daily resource cycle of positive energization that can be further used by the individual to manage performance episodes more effectively at work. Thus, we propose:

-

H6: Daily off-job crafting for autonomy and for mastery are positively related to next-day self-rated performance through matching recovery experiences (daily control and mastery)

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study was conducted among knowledge workers in two Norwegian organizations (i.e., bank employees including financial advisers, accountants, technical staff, and managers, and university employees including lecturers, researchers, and administrative staff). Data were collected in January and February 2022. We obtained approval from SIKT (formerly Norwegian Center for Research Data, project number 322106) prior to data collection. A total of 1929 university and 700 bank employees were approached to take part, with an incentive that they received personalized feedback after the study based on their own results. One week before the start of the daily diary period, participants filled a questionnaire about background characteristics including the informed consent sent via e-mail. This was followed by two daily questionnaires from Mondays to Thursdays during two consecutive weeks (i.e., sixteen questionnaires in total) with individual links, sent via SMS. We excluded Friday measurements from the study design due to the “Friday effect”, which denotes that employees’ levels of positive affect and energy tend to increase substantially on Fridays after staying rather stable from Monday to Thursday, with opposite trends for negative affect and fatigue (Stone et al., 2012; Weigelt et al., 2021). The first questionnaire instructed participants to think about their experiences at work that day, measuring work stress and self-rated performance. This questionnaire could be completed between 1 and 5 PM. The second questionnaire referred to off-job experiences, measuring proactive recovery strategies, recovery experiences, off-job stress, and affect. It could be completed between 9 PM and 1 AM. Median questionnaire response time ranged from 82 to 144 s for the first (afternoon) questionnaire, and from 159 to 248 s for the second (evening) questionnaire. This is slightly more than the average response time of 105 s per questionnaire with an average of 5 questionnaires per day reported in a systematic review of prior smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment studies, but compensated by the lower number of questionnaires per day in our study (de Vries et al., 2021). A total of 381 participants (14.5% of the invited) filled the background questionnaire, and the diary entries resulted in a total of 3263 data points. We removed participants who worked for less than 16 h per week (n = 4, with a total of 24 diary responses). Moreover, we deleted the afternoon diary responses for days when a participant reported that they had not been working (n = 77). In addition, a total of 17 diary responses were deleted due to inappropriate timing of the answer (e.g., when a participant started answering a questionnaire in the evening but only finished it the next morning). After these steps, we followed the recommendations of Newman (2014) and Schafer and Graham (2002) and used all available data for our analyses instead of listwise deletion of participants. This resulted in a total of 377 participants and 3145 diary data points across the study period (average 8.34 surveys per participant). Little’s MCAR test was nonsignificant, indicating that data was missing at random (χ2 = 37,904.118, df = 48,179, p = 1.00). Participants were on average 48.2 years old (ranging from 24 to 70 years), and more often female (69%) than male (31%). A third (33.2%) had completed a bachelor’s degree or lower, two-fifths (41.3%) had a master’s degree, and a fourth (25.5%) had a doctoral degree. Most (72.1%) were married or lived together with a partner. About one-ninth (12%) had children under the age of six. Average weekly working hours were 40.8 (SD = 7.2, including overtime). The participants worked partly or fully from home almost every other workday (41.9% of all measurement days).

Measures

Participants reported on scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), except where it is otherwise noted. Daily proactive recovery strategies were measured with 12 items (i.e., three items per dimension) from the Needs-based Off-job Crafting Scale (Kujanpää et al., 2022). Multilevel reliabilities (ωw for within- and ωb for between-level reliability; Lai, 2021) were ωw = 0.89 and ωb = 0.80 for crafting for detachment (example item “Today, I’ve arranged my off-job time so that I distance myself from work-related tasks”), ωw = 0.81 and ωb = 0.77 for crafting for relaxation (“Today, I’ve planned my off-job activities so that I get relief from stress”), ωw = 0.76 and ωb = 0.79 for crafting for autonomy (“Today, I’ve organized my off-job activities so that I determine my own course of action”), and ωw = 0.71 and ωb = 0.80 for crafting for mastery (“Today, I’ve organized my off-job activities so that I put my skills, knowledge or abilities into action”).

Daily recovery experiences were measured with 12 items (i.e., three items per dimension) from the Recovery Experience Questionnaire (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Each item started with “today, during time after work”. Multilevel ω were ωw = 0.83 and ωb = 0.77 for detachment from work (“I forgot about work”), ωw = 0.87 and ωb = 0.76 for relaxation (“I kicked back and relaxed”), ωw = 0.89 and ωb = 0.81 for control (“I felt like I could decide for myself what to do”), and ωw = 0.82 and ωb = 0.74 for mastery (“I learned new things”).

Off-job and work stress were measured with the item “Today, on a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate the amount of stress you felt during off-job time/in your job, where 1 is no stress and 10 is extreme stress?” from the Stress in General Scale (SIGS; Le Fevre et al., 2015; Stanton et al., 2001). Negative and positive affect were measured with the short form of the international Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (I-PANAS-SF; Thompson, 2007), which includes ten items (five for each dimension). Multilevel ω were ωw = 0.78 and ωb = 0.85 for negative (“This evening, I am feeling upset”) and ωw = 0.78 and ωb = 0.80 for positive affect (“This evening, I am feeling inspired”).

Self-rated work performance was measured with two items developed by Demerouti et al. (2015). Example item is “Today, I performed well”. Answers could range from 1 (“not true at all”) to 5 (“totally true”). Inter-item correlations for the two items ranged from 0.44 to 0.68 (M = 0.57) across all measurement points.

Analyses

As the data had a nested structure (days nested in participants), we conducted multilevel analyses with Mplus 8.7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). To examine the structure of recovery (i.e., proactive strategies and experiences) and affect (i.e., negative and positive), we conducted multilevel confirmatory factor analyses (MCFA) with Maximum Likelihood estimation (Hox, 2010). We fully saturated the MCFA models at the between-person level to examine the fit within persons. A null model (including only the intercept) was then created for each variable of the study to examine variance at each level (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992).

Since our analyses included within-person indirect effects, which are most often skewed, we used Bayesian estimation with non-informative priors to test our hypotheses (Geldhof et al., 2014; Muthén & Asparouhov, 2011). Bayesian analysis is particularly suitable for complex models and models that violate standard analysis assumptions, as is the case in our study testing within-person mediation including control variables (Kruschke et al., 2012). A stepwise approach was used for testing the within-person mediation hypotheses (Zhang et al., 2009). First, we conducted three direct-effects models using Bayesian multilevel path modelling (i.e., a first model examining the paths from PRS to recovery experiences, a second model examining the paths from recovery experiences to outcomes measured the same day, and a third model examining the paths from recovery experiences to work stress and performance measured the following day). Person-mean centering was used to divide variance at the between- and the within-levels. We included the relationships between predictors and outcomes simultaneously at both the within- and between-levels (Preacher et al., 2010). The lags from Thursday to Monday were excluded from all lagged analyses. Second, to estimate indirect effects, we conducted Bayesian within-person mediation models for each of the off-job crafting dimension → matching recovery experience → outcome paths (e.g., off-job crafting for detachment → experienced detachment → daily off-job stress). To test for within-person mediation, we person-mean centered all predictors and estimated confidence intervals for indirect effects using a Monte Carlo simulation with 20,000 iterations, as recommended for multilevel frameworks (Preacher & Selig, 2012; Preacher et al., 2010).

To account for the chronological structure of the data (i.e., for the role of time), we added time (i.e., day of the study) as a covariate in all models testing the direct and indirect effects. Moreover, to control for the days when participants had a day off from work, we also added “day off from work” (yes/no) as a within-level predictor in each of these models.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

MCFA for proactive recovery strategies and recovery experiences showed that an eight-factor model with each proactive recovery strategies and recovery experiences scale dimension as a separate factor had a between good to acceptable fit (χ2 = 1279.079, df = 224, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR (within) = 0.06, SRMR(between) = 0.02). All items had substantial standardized loadings on their latent factor at the within-level, with coefficients ranging from 0.61 to 0.90 (all p values < 0.001). The eight-factor model fitted the data better than a one-factor model (χ2 = 7542.128, df = 252, CFI = 0.72, TLI = 0.38, RMSEA = 0.13, SRMR(within) = 0.12, SRMR(between) = 0.05, Δχ2 = 6263.049, Δdf = 28, p < 0.001), a two-factor model with all proactive recovery strategies as one factor and all recovery experiences as another factor (χ2 = 6838.773, df = 251, CFI = 0.74, TLI = 0.44, RMSEA = 0.13, SRMR(within) = 0.12, SRMR(between) = 0.04, Δχ2 = 5559.694, Δdf = 27, p < 0.001), and a four-factor model combining each proactive recovery strategy with each matching recovery experience (e.g., factor 1 with both crafting for detachment and detachment experiences; χ2 = 3330.532, df = 246, CFI = 0.88, TLI = 0.73, RMSEA = 0.09, SRMR(within) = 0.09, SRMR(between) = 0.04, Δχ2 = 2051.453, Δdf = 22, p < 0.001). Similarly, a two-factor model for affect with negative and positive affect as separate dimensions (χ2 = 353.335, df = 34, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.85, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR(within) = 0.04, SRMR(between) = 0.01) had a better fit than a one-factor model (χ2 = 1761.822, df = 35, CFI = 0.69, TLI = 0.21, RMSEA = 0.18, SRMR(within) = 0.16, SRMR (between) = 0.05, Δχ2 = 1408.487, Δdf = 1, p < 0.001).

The null models showed that there was sufficient variability at the within and between-levels in each study variable to conduct the multilevel analyses (Intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.31-0.66, Table 1).

The direct-effects models (Tables S1–S3 in the Supplementary Information) showed that all proactive recovery strategies positively predicted matching recovery experiences at the within-person level. All recovery experiences negatively predicted daily off-job stress and negative affect and positively predicted daily positive affect, with the exception that relaxation was unrelated to positive affect. Only detachment negatively predicted next-day work stress, whereas only control positively predicted next-day performance.

Avoidance-Focused Mediation Process

Regarding models examining within-person mediation, daily off-job crafting for detachment had a negative indirect effect on daily off-job stress through detachment experiences (B = − 0.29, p < 0.001) but not on next-day work stress (B = − 0.08, p = 0.09; Tables 2 and 3). Similar results were found for off-job crafting for relaxation, which had a negative effect on off-job stress (B = − 0.49, p < 0.001) through relaxation experiences but not on next-day work stress (B = 0.01, p = 0.48). Off-job crafting for detachment and for relaxation had a significant negative direct effect on off-job stress, suggesting partial mediation. In addition, off-job crafting for relaxation had a negative direct effect on next-day work stress. As such, H1a was supported, whereas H1b was not supported. Avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies predicted matching recovery experiences at the day-level, which in turn was related to lower off-job stress, but not to next-day work stress.

For affect, off-job crafting for detachment had a negative indirect effect on negative affect (B = − 0.10, p < 0.001) through detachment experiences, but not on positive affect (B = 0.02, p = 0.17; Table 2). Similarly, off-job crafting for relaxation had a negative effect on negative affect (B = − 0.09, p < 0.001) through relaxation experiences, but not on positive affect (B = 0.01, p = 0.41). Off-job crafting for detachment and for relaxation had a significant negative direct effect on negative affect and a positive direct effect on positive affect, suggesting partial mediation. Thus, H2a was supported and H2b was not supported. Daily avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies predicted lower negative affect, but not positive affect through matching recovery experiences.

For self-rated performance, neither crafting for detachment (B = − 0.00, p = 0.45) or crafting for relaxation (B = − 0.00, p = 0.49) predicted next-day performance through matching recovery experiences (Table 3). Thus, H3 was not supported, as although avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies predicted matching recovery experiences at the day-level, these effects did not lead to a higher performance on the following workday.

Approach-Focused Mediation Process

Regarding the within-person mediation models for approach-focused proactive recovery strategies, off-job crafting for autonomy had a negative effect on off-job stress (B = − 0.46, p < 0.001) through control experiences, but not on next-day work stress (B = − 0.05, p = 0.25; Tables 2 and 3). Off-job crafting for mastery did not have a significant indirect effect on off-job stress (B = 0.05, p = 0.20) or next-day work stress (B = − 0.11, p = 0.08). Off-job crafting for autonomy and for mastery had a significant negative direct effect on off-job stress, suggesting partial mediation. Moreover, off-job crafting for autonomy had a negative direct effect on next-day work stress. As such, H4a was partially supported, and H3b was not supported. Approach-focused proactive recovery strategies predicted matching recovery experiences at the day-level, which in turn was related to lower off-job stress (for crafting for autonomy) but not to next-day work stress.

For affect, off-job crafting for autonomy had a negative effect on negative affect (B = − 0.13, p < 0.001) through control experiences, but not on positive affect (B = 0.02, p = 0.26; Table 2). In contrast, off-job crafting for mastery had a positive effect on positive affect (B = 0.16, p < 0.001) through mastery experiences, but not on negative affect (B = − 0.00, p = 0.43). Off-job crafting for autonomy and for mastery had a significant negative direct effect on negative affect and a positive direct effect on positive affect, suggesting partial mediation. As such, H5a and H5b were partially supported. Daily off-job crafting for mastery was related to a higher positive affect through mastery experiences, whereas off-job crafting for autonomy displayed a similar pattern of results as avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies in negatively predicting negative affect (but not positive affect) through matching recovery experiences.

In line with H6, off-job crafting for autonomy had a positive effect on lagged self-rated work performance through control experiences at the within-person level (B = 0.06, p < 0.05; Table 3). The direct effect between off-job crafting for autonomy and self-rated performance was not significant, suggesting full mediation. Off-job crafting for mastery did not significantly predict next-day performance through mastery experiences (B = − 0.03, p = 0.17). However, off-job crafting for mastery had a positive direct effect on next-day self-rated performance. Thus, H6 received partial support. Off-job crafting autonomy predicted next-day self-rated work performance through control experiences, whereas crafting for mastery was directly related to next-day performance but did not have a significant indirect effect through mastery experiences.

Additional Analyses

To test whether the effects of proactive recovery strategies persisted for next-day off-job stress and affect, we conducted further Bayesian within-person mediation models with lagged outcomes (e.g., off-job crafting for detachment → experienced detachment → next-day off-job stress). Only one indirect effect was significant, indicating that off-job crafting for autonomy predicted higher next-day positive affect through control experiences (Table S4 in the Supplementary Information). However, all proactive recovery strategies were directly related to lower next-day off-job stress and to higher next-day positive affect (but not to next-day negative affect).

Discussion

As the working life intensifies and boundaries between work and off-job life are becoming increasingly blurred, having effective and sufficient recovery processes is critical for sustaining employee wellbeing and performance (Sonnentag et al., 2022). Our study focusing on within-person effects shows that employees can promote their daily recovery experiences through engaging in avoidance- and approach-focused proactive recovery strategies. Furthermore, all proactive recovery strategies have positive associations to daily happiness outcomes, whereas crafting for autonomy is also associated to next-day productivity. More specifically, we found that daily off-job crafting for detachment, for relaxation, and for autonomy was related to a lower daily off-job stress and negative affect through matching recovery experiences, whereas daily off-job crafting for mastery was related to a higher daily positive affect through mastery experiences. Off-job crafting for relaxation and for autonomy was related to a lower next-day work stress, but these effects were not mediated by matching recovery experiences. Daily off-job crafting for autonomy predicted a higher self-rated work performance on the following day through control experiences.

Theoretical Implications

Our study sheds light for the first time on the effects of specific proactive recovery strategies at the day-level. The results showed that proactive recovery strategies are positively related to daily employee wellbeing through matching recovery experiences. As such, we provide support for a key proposition of the integrative needs model of crafting that crafting efforts predict satisfaction in matching psychological needs (de Bloom et al., 2020), expanding earlier findings which have either used longer time frames (Kujanpää et al., 2022) or treated crafting as a unidimensional construct (Kosenkranius et al., 2023). Proactive off-job recovery strategies provide an important means for employees to self-manage their own recovery in a self-initiated, intentional way, complementing proactive strategies in the work domain (e.g., Hur & Shin, 2023; Op den Kamp et al., 2018) and other antecedents of recovery experiences such as habits or family support (Park & Fritz, 2015; Sonnentag & Jelden, 2009).

The within-person mediation results regarding stress and affective wellbeing showed that daily avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies are related to a lower off-job stress and negative affect through matching recovery experiences, whereas the indirect effects were not significant with next-day work stress and positive affect as outcomes. Drawing from the effort-recovery model, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies are valuable for intentionally restoring and supporting the homeostatic balance of the body and the mind during off-job time (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). Crafting off-job time with an avoidance focus may have become especially salient for protecting against ill-being in an intensifying work-life, as employees experiencing intensified job demands could find it more useful to proactively decrease their mental load in the off-job domain instead of taking on new challenging or demanding activities (Kubicek & Tement, 2016). Our results show that, in contrast to avoidance-focused job crafting which tends to be positively related to ill-being indicators such as job stress and burnout symptoms (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019; Sakuraya et al., 2017), avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies may be used as an adaptive strategy in the off-job domain to protect oneself against daily ill-being.

Contrary to expectations, avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies were unrelated to next-day self-rated work performance. It may be that avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies, while helpful against ill-being, primarily reflect a process wherein employees intentionally direct their attention away from their work-related obligations in order to sustain their homeostatic balance. This proactive focus on disengaging from work-related thoughts and seeking relaxation during off-job time may thus mainly alleviate employees’ negative states such as stress instead of bringing new resources that are conducive to work performance (see also Fritz et al., 2010a, b).

Regarding the within-person indirect effects of approach-focused proactive recovery strategies, off-job crafting for mastery predicted positive affect through mastery experiences but not off-job stress, negative affect, or next-day work stress, showing a mostly opposite pattern of results as compared to avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies. Drawing from the conservation of resources theory, since crafting for mastery requires employees to actively use their energy reservoirs in order to seek new challenges and possibilities for learning, it can be particularly beneficial for initiating new resources cycles that promote positive well-being such as positive affect (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Tsaur et al., 2023). On the other hand, due to these energy investments involved in crafting for mastery, this strategy could be less effective for fixing resource imbalances indicated by states such as work stress (see also Sonnentag, 2018). Interestingly, crafting for autonomy, an approach-focused strategy, showed a rather similar pattern as avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies in relation to daily stress and affective wellbeing. Despite its potential for building new personal resources, crafting for autonomy may, in the context of off-job life, be primarily used as a self-preservation strategy, protecting the self from the negative effects of daily stress. This idea is in line with studies in the field of leisure sciences, which have emphasized how the leisure domain can provide an autonomy-supporting, restorative space for employees to be themselves and get a break from daily stress and tension (Iwasaki, 2007; Iwasaki et al., 2005).

Off-job crafting for autonomy had a fully mediated positive indirect effect on next-day self-rated work performance through control experiences. In line with the conservation of resources theory, off-job crafting for autonomy provides employees with resource accumulation in the off-job domain that is conducive to positive spillover for work performance. As autonomy is a key psychological need which, when satisfied, translates to optimal functioning across different life domains (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Milyavskaya & Koestner, 2011), it makes sense that off-job crafting for autonomy has the potential to support both employee happiness and productivity. Crafting for autonomy helps employees to express themselves and to engage with more personally valuable activities during off-job time (see also Iwasaki et al., 2018; Ni et al., 2022). This proactive restoration of one’s need for autonomy through off-job crafting efforts can provide the individual with resources that are further invested in active involvement, concentration, and commitment in performance episodes during the following workday (see also Radel et al., 2011; Sheldon et al., 1998). In line with this notion, crafting for autonomy predicted next-day (but not within-day) positive affect through control experiences, indicating resource accumulation over the week. As such, providing support to the integrative needs model of crafting, crafting for autonomy may be a useful means for employees to intentionally form resource cycles that transfer across life domains (de Bloom et al., 2020; Hobfoll, 2011). In a similar vein, autonomy-supporting behaviors such as creative leisure activities (de Bloom et al., 2018) and internet leisure browsing during work breaks (Coker, 2011) have been previously linked to a higher self-rated work performance. In contrast to crafting for autonomy, crafting for mastery may be closer alike to serious leisure pursuits, depicted as an individual’s systematic focus on developing mastery, expertise, and a “leisure career” within a rather narrow set of specific activities in the leisure or volunteering domain (Stebbins, 1992, 2015). Even though such pursuits can bring mastery experiences and build a sense of positive affect, the potentially narrow scope of mastery developed through crafting for mastery may not ultimately be easily transferable to daily tasks in the work domain, which may require different skills than those provided by one’s hobbies or volunteering pursuits.

All proactive recovery strategies were directly related to daily stress and affective wellbeing, effects which were only partially mediated by matching recovery experiences. Furthermore, while all proactive recovery strategies were directly related to off-job stress and positive affect (but not negative affect) in the lagged analyses, these effects were mostly not mediated by matching recovery experiences. We also found that crafting for relaxation and for autonomy had a direct negative effect on next-day work stress, and crafting for mastery had a positive direct effect on next-day self-rated performance.

There are several potential explanations to these findings. Firstly, it may be that other factors in addition to recovery experiences, such as mindfulness as a sense of relaxed, volitional awareness gained through crafting for relaxation or for autonomy (see also Op den Kamp et al., 2023), or enhanced self-efficacy gained through crafting for mastery (see also Lyons, 2008; Sonnentag & Kruel, 2006), could promote the translation of proactive recovery strategies to next-day outcomes. Secondly, changes in sleep quality or duration on the following night could facilitate or interfere with the transfer of proactive recovery strategies to next-day outcomes (see also Hur & Shin, 2023). Thirdly, proactive recovery strategies in the off-job domain may result in further crafting efforts at work to complement such strategies, as home-to-work spillover of crafting has been demonstrated (Haun et al., 2022). Thus, employees might effectively combine proactive off-job strategies with subsequent job crafting strategies, potentially explaining the direct effects found between proactive recovery strategies and next-day work stress and performance. Fourthly, a part of the impact of proactive recovery strategies could be due to enhancement of non-matching recovery experiences. For instance, crafting for relaxation by deciding to do a brief meditation before going to bed to calm down and relax the body and mind could in addition help one forget work-related thoughts, enhancing detachment. We conducted a supplemental relative weight analysis with Pratt indices (Liu et al., 2014), which showed that a majority of the variation in daily recovery experiences predicted by daily proactive recovery strategies could be attributed to matching proactive recovery strategies (Table S5 in the Supplementary Information). This was particularly the case for mastery and detachment experiences. Thus, such non-matching paths are likely to have a smaller influence at the day-level compared to the effects of matching strategies, supporting the matching perspective of the integrative needs model of crafting (de Bloom et al., 2020). Finally, it is interesting to note that negative affect was no longer directly predicted by proactive recovery strategies in the additional lagged analyses, indicating that the effects for negative affect can fade out more quickly than do effects for off-job stress and positive affect. Negative affect during daily off-job time may be rather transient and situationally dependent, making it difficult to create sustained change in negative affect through proactive strategies (Fritz et al., 2010a, 2010b).

Practical Implications

The context of work and off-job time is rapidly changing due to work intensification and technological advances. By crafting their recovery time, employees can meet some of these challenges proactively in order to promote their wellbeing and performance in a rapidly changing work and off-job time. The negative associations of avoidance-focused proactive recovery strategies for off-job stress and negative affect, together with the null findings for performance demonstrate that, especially during stressful days, employees may find it useful to prioritize their happiness by proactively shaping their off-job time to enhance recovery instead of focusing on optimizing their performance at work (see also Wright & Cropanzano, 2000). Furthermore, we find that in addition to promoting wellbeing, crafting for autonomy as an approach-focused proactive recovery strategy can also have benefits for next-day performance, highlighting that employees’ proactive focus on their own off-job time is not in opposition to organizational goals but in fact promotes a healthier and more productive workplace.

Our results are encouraging for the further development of recovery interventions, which have shown that experiences of psychological detachment can be promoted through a focus on everyday recovery (Karabinski et al., 2021). Workplace interventions could more explicitly focus on the role of individual proactivity that may be necessary to initiate and sustain behavioral change in relation to employees’ daily recovery processes. Moreover, as proactive efforts require mental energy to perform (de Bloom et al., 2020), organizations should provide employees with enough resources through practices such as allowing flexible time off, providing social support, and protecting against a constantly high time pressure (Kossek et al., 2014). Such practices could enable employees to use proactive recovery strategies flexibly and effectively on those days when they deem it most useful.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study is not without limitations. First, as is common with studies testing within-person mediation (e.g., Li et al., 2022; Lydon-Staley et al., 2020; Veldman et al., 2021), some of the tested effects were concurrent within-level associations. However, our study design with two measurement points per day allowed us to use multiple-item scales for most of our measures without burdening the participants too much, allowing to examine scale reliability and structural properties at the within-level (see also Ohly et al., 2010). Future studies examining proactive recovery strategies could implement more daily measurements, for example to allow for an examination of how the impact of different proactive recovery strategies on recovery experiences develops during the course of a free evening. Moreover, having several measurement times per day during off-job time could uncover whether strategies enacted in the morning or in the evening yield best results for recovery, wellbeing, and performance. However, as crafting is an ongoing process instead of a momentary experience (Berg et al., 2013), such studies would need to carefully consider the time frames used in measuring crafting to allow for having a sufficient time window for crafting processes to occur. Furthermore, future research could examine potential reverse effects between proactive recovery strategies and recovery experiences. For example, feeling detached from work-related thoughts could promote engagement in proactive recovery strategies by allowing such strategies to be enacted without mental interruptions. Such reciprocal relationships wherein proactive recovery strategies enhance daily recovery experiences, which in turn energize the use of further strategies, could initiate positive cycles during off-job time, forming wellbeing-promoting resource cycles (Hobfoll, 2012). Moreover, future studies could examine potential synergistic effects of proactive recovery strategies and proactive work behaviors such as job crafting in predicting employee happiness and productivity across life domains (de Bloom et al., 2020; Haun et al., 2022).

Second, we used only self-report measures to examine our study variables. Since proactive recovery strategies are self-initiated and self-targeted, as well as enacted during off-job time when others may not always be present for observation, self-report questionnaires are arguably the most accurate means of measurement for this variable (de Bloom et al., 2020; see also Parker et al., 2006). However, future studies could incorporate objective or other-rated measures of outcomes, for instance to determine whether proactive recovery strategies can also influence physiological indicators of stress such as daily heart rate variability or cortisol levels. Moreover, measuring partner-rated emotional displays could provide interesting findings on whether proactive recovery strategies also produce changes in outward expressions of affect in addition to affective wellbeing.

Third, although our study design with daily measurements from Monday to Thursday across a period of two weeks allowed us to test our hypotheses during the course of the working week, avoiding the Friday effect (Stone et al., 2012), we did not examine proactive recovery strategies and recovery experiences during the weekend. Future research could test whether proactive recovery strategies used in the weekend influence wellbeing and performance during the subsequent working week. Since weekends typically offer employees with more opportunities to spend time in activities such as hobbies, childcare, and volunteering than do free evenings (Miranda, 2011), engaging in proactive recovery strategies during weekends may have stronger or more long-lasting effects on subsequent performance at work. Finally, while the participants in our sample performed knowledge-intensive work, forming a fruitful context for a pioneering investigation on daily proactive recovery strategies, the generalizability of results may be limited to well-educated, white-collar employees. Future research would benefit from examining proactive recovery strategies also among blue-collar employees, who, as compared to white-collar employees, may see more value in engaging in avoidance-focused strategies in order to separate themselves from work and reduce strain (see also Kinnunen et al., 2016; Nielsen et al., 2017). Furthermore, as work-life is rapidly changing and intensifying, taking action to proactively shape daily recovery time may be especially vital for workers in fluid employment arrangements such as freelancers, shift, and contract workers (Sonnentag et al., 2022). To conclude, our study highlights that employees do engage in daily proactive off-job recovery strategies, positively influencing their daily recovery, wellbeing, and self-rated performance. As such, a part of being a “happy and productive worker” (Wright & Cropanzano, 2000) can mean taking action to shape one’s recovery from work stress during off-job time.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abdel Hadi, S., Bakker, A. B., & Häusser, J. A. (2021). The role of leisure crafting for emotional exhaustion in telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 34(5), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1903447

Bakker, A. B. (2017). Strategic and proactive approaches to work engagement. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.002

Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job Demands-Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2019). Daily job crafting and momentary work engagement: A self-determination and self-regulation perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.005

Bakker, A. B., Hetland, J., Olsen, O. K., & Espevik, R. (2019). Daily strengths use and employee well-being: The moderating role of personality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(1), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12243

Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barros, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (2005). An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1054–1068. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1054

Berg, J. M., Grant, A. M., & Johnson, V. (2010). When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organization Science, 21(5), 973–994. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0497

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81–104). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14183-005

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579–616. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030

Brauchli, R., Kerksieck, P., Tušl, M., & Bauer, G. F. (2023). Staying healthy during COVID-19 crisis: Well-being and salutogenic crafting among German and Swiss working population. Health Promotion International, 38(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac004

Bruning, P. F., & Campion, M. A. (2018). A role-resource approach-avoidance model of job crafting: A multimethod integration and extension of job crafting theory. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 499–522. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0604

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models for social and behavioral research: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Chawla, N., MacGowan, R. L., Gabriel, A. S., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2020). Unplugging or staying connected? Examining the nature, antecedents, and consequences of profiles of daily recovery experiences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000423

Chen, I. S. (2023). Using leisure crafting to reduce emotional exhaustion at home during the COVID-19 pandemic through better sleep and not thinking about the pandemic. Stress and Health, 39(5), 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3243

Coker, B. L. S. (2011). Freedom to surf: The positive effects of workplace Internet leisure browsing. New Technology, Work and Employment, 26(3), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2011.00272.x

Daniels, K. (2012). Job characteristics and problem-solving. In A. Bakker & K. Daniels (Eds.), A Day in the Life of a Happy Worker (pp. 58–71). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203078990

de Bloom, J., Rantanen, J., Tement, S., & Kinnunen, U. (2018). Longitudinal leisure activity profiles and their associations with recovery experiences and job performance. Leisure Sciences, 40(3), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2017.1356254

de Bloom, J., Vaziri, H., Tay, L., & Kujanpää, M. (2020). An identity-based integrative needs model of crafting: Crafting within and across life domains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(12), 1423–1446. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000495

de Vries, L. P., Baselmans, B. M. L., & Bartels, M. (2021). Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment of well-being: A systematic review and recommendations for future studies. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(5), 2361–2408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00324-7

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Geurts, S. A. E., & Taris, T. W. (2009). Daily recovery from work-related effort during non-work time. In S. Sonnentag, P. L. Perrewé, & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Current perspectives on job-stress recovery: Research in occupational stress and well being (pp. 85–124). Emerald Group.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2015). Productive and counterproductive job crafting: A daily diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039002

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology - The Broaden-and-Build Theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226.

Fritz, C., Sonnentag, S., Spector, P. E., & McInroe, J. A. (2010a). The weekend matters: Relationships between stress recovery and affective experiences. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(8), 1137–1162. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.672

Fritz, C., Yankelevich, M., Zarubin, A., & Barger, P. (2010b). Happy, healthy, and productive: The role of detachment from work during nonwork time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 977–983. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019462

Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J., & Zyphur, M. J. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032138

Hakanen, J. J., Seppälä, P., & Peeters, M. C. W. (2017). High job demands, still engaged and not burned out? The role of job crafting. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24(4), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9638-3

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in Conservation of Resources Theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Haun, V. C., Mülder, L. M., & Schmitz, A. L. (2023). From job crafting to home crafting and back again: A shortitudinal study on the spillover between job and home crafting. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 96(2), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12417

Headrick, L., Newman, D. A., Park, Y. A., & Liang, Y. (2023). Recovery experiences for work and health outcomes: A meta-analysis and recovery-engagement-exhaustion model. Journal of Business and Psychology, 38(4), 821–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09821-3

Heydarifard, Z., & Krasikova, D. V. (2023). Losing sleep over speaking up at work: A daily study of voice and insomnia. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(9), 1559–1572. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001087

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hobfoll, S. E. (2012). Conservation of resources and disaster in cultural context: The caravans and passageways for resources. Psychiatry, 75(3), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.3.227

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hox, J. J. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315650982

Hur, W.-M., & Shin, Y. (2023). Is resting and sleeping well helpful to next-day job crafting? Daily relationship between recovery experiences, sleep quality, feelings of recovery, and job crafting. Applied Psychology, 72(4), 1608–1623. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12454

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (2015). Conscious versus nonconscious mind and leisure. Leisure Sciences, 37(4), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2015.1005560

Iwasaki, Y. (2007). Leisure and quality of life in an international and multicultural context: What are major pathways linking leisure to quality of life? Social Indicators Research, 82(2), 233–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9032-z

Iwasaki, Y. (2017). Contributions of leisure to “meaning-making” and its implications for leisure studies and services. Annals of Leisure Research, 20(4), 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2016.1178591

Iwasaki, Y., & Mannell, R. C. (2000). Hierarchical dimensions of leisure stress coping. Leisure Sciences, 22(3), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409950121843

Iwasaki, Y., Mactavish, J., & Mackay, K. (2005). Building on strengths and resilience: Leisure as a stress survival strategy. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 33(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880412331335894

Iwasaki, Y., Messina, E. S., & Hopper, T. (2018). The role of leisure in meaning-making and engagement with life. Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1374443

Jensen, J. M., Patel, P. C., & Messersmith, J. G. (2013). High-performance work systems and job control: Consequences for anxiety, role overload, and turnover intentions. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1699–1724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311419663

Karabinski, T., Haun, V. C., Nübold, A., Wendsche, J., & Wegge, J. (2021). Interventions for improving psychological detachment from work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(3), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000280

Kelly, C. M., Strauss, K., Arnold, J., & Stride, C. (2020). The relationship between leisure activities and psychological resources that support a sustainable career: The role of leisure seriousness and work-leisure similarity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117(March 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103340

Kinnunen, U., Rantanen, J., de Bloom, J., Mauno, S., Feldt, T., & Korpela, K. (2016). The role of work–nonwork boundary management in work stress recovery. International Journal of Stress Management, 23(2), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039730

Kosenkranius, M., Rink, F., Kujanpää, M., & De Bloom, J. (2021). Motives for crafting work and leisure: Focus on opportunities at work and psychological needs as drivers of crafting efforts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312294

Kosenkranius, M., Rink, F., Weigelt, O., & de Bloom, J. (2023). Crafting and human energy: Needs-based crafting efforts across life domains shape employees’ daily energy trajectories. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 28(3), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000347

Kossek, E. E., Valcour, M., & Lirio, P. (2014). The sustainable workforce: Organizational strategies for promoting work-life balance and wellbeing. In C. Cooper & P. Chen (Eds.), Wellbeing in the workplace: From stress to happiness (Vol. 3). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell030

Kreiner, G. E., Hollensbe, E. C., & Sheep, M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work-home interface via boundary work tactics. The Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 704–730. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.43669916

Kruschke, J. K., Aguinis, H., & Joo, H. (2012). The time has come: Bayesian methods for data analysis in the organizational sciences. Organizational Research Methods, 15(4), 722–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112457829

Kubicek, B., & Tement, S. (2016). Work intensification and the work-home interface: The moderating effect of individual work-home segmentation strategies and organizational segmentation supplies. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 15(2), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000158

Kujanpää, M., Syrek, C., Lehr, D., Kinnunen, U., Reins, J. A., & de Bloom, J. (2020). Need satisfaction and optimal functioning at leisure and work: A longitudinal validation study of the DRAMMA model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 681–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00247-3

Kujanpää, M., Syrek, C., Tay, L., Kinnunen, U., Mäkikangas, A., Shimazu, A., Wiese, C. W., Brauchli, R., Bauer, G. F., Kerksieck, P., Toyama, H., & de Bloom, J. (2022). Needs-based off-job crafting across different life domains and contexts: Testing a novel conceptual and measurement approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 959296. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.959296

Lai, M. H. C. (2021). Composite reliability of multilevel data: It’s about observed scores and construct meanings. Psychological Methods, 26(1), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000287

Le Fevre, M., Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2015). Which workers are more vulnerable to work intensification? An analysis of two national surveys. International Journal of Manpower, 36(6), 966–983. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-01-2014-0035