Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major global health concern and represents a significant public health challenge in Hungary, where it exhibits some of the highest morbidity and mortality rates in the European Union. The Mediterranean diet has been suggested to reduce the incidence of CRC, but comprehensive evidence from diverse study designs is needed to substantiate this effect. A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, ClinicalTrials.gov, CENTRAL, and the Web of Science to identify randomized controlled trials and human clinical trials from 2008 to 2024 to identify relevant studies. Statistical analysis was performed using the https://metaanalysisonline.com web application using a random effects model to estimate the pooled hazard rates (HRs). Forest plots, funnel plots, and Z-score plots were utilized to visualize results. We identified 15 clinical trials and 9 case–control studies, encompassing a total of 2,217,404 subjects. The pooled analysis indicated that adherence to the Mediterranean diet significantly reduced the prevalence of CRC (HR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.78–0.91, p < 0.01). This protective effect was consistent across sexes, with HRs of 0.85 (95% CI = 0.75–0.97, p = 0.01) for males and 0.88 (95% CI = 0.79–0.99, p = 0.03) for females. Case–control studies specifically showed a substantial effect (HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.38–0.68, p < 0.01). Notable heterogeneity was observed across studies, yet the a priori information size was substantially below the cumulative sample size, ensuring sufficient data for reliable conclusions. The findings from this meta-analysis reinforce the protective role of the Mediterranean diet against CRC. The results of this meta-analysis will inform dietary interventions designed to mitigate CRC risk, which are conducted within the framework of the Semmelweis Study, an ongoing comprehensive cohort study at Semmelweis University, designed to explore the multifaceted causes of unhealthy aging in Hungary. These interventions aim to explore the practical application of Mediterranean dietary patterns in reducing CRC incidence among the Hungarian population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the most prevalent and lethal malignancies worldwide, with rising incidence rates particularly marked in the European Union (EU) [1,2,3,4]. CRC is increasingly recognized as an age-related disease, with the majority of cases diagnosed in individuals over the age of 50 [2, 4, 5]. This correlation underscores the importance of fundamental cellular and molecular aging processes in the development of CRC, where DNA damage and epigenetic dysregulation become prevalent over time, facilitated by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress [5, 6].

In Hungary, the unfavorable epidemiological situation—characterized by some of the highest rates of CRC in the European Union—can largely be attributed to the unhealthy aging of its population [7, 8]. A critical factor contributing to this phenomenon is lifestyle, particularly dietary habits [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The typical Hungarian diet, high in processed foods and low in fresh fruits and vegetables, aligns poorly with the principles of healthy aging [12, 13]. This dietary pattern not only exacerbates the risk factors associated with aging but also directly influences the incidence of age-related diseases like CRC [4, 18, 19]. Thus, the prevailing health challenges in Hungary, particularly the high prevalence of CRC, are a stark indicator of the broader issues stemming from an unhealthy lifestyle, with poor diet playing a pivotal role. This disturbing trend underscores the urgent need for effective preventive strategies and interventions tailored to the Hungarian population.

The Mediterranean diet is celebrated for its health benefits, primarily due to its rich composition of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats, primarily olive oil, along with moderate consumption of fish and poultry [20]. Numerous epidemiological studies have linked adherence to the Mediterranean diet with reduced incidences of chronic diseases, notably cardiovascular diseases and various forms of cancer, including colorectal carcinoma [16, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The protective effects of the Mediterranean diet are often attributed to its high content of dietary fiber, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory compounds, which are thought to play crucial roles in cancer prevention. In spite of its benefits, current evidence shows a progressive abandonment of this dietary pattern in favor of more “Westernized” dietary habits, representing a potential threat to human health and the local environment [29, 30].

In response to the critical health challenge posed by unhealthy aging in Hungary, the Semmelweis Study was initiated by Semmelweis University [8]. This prospective epidemiological survey aims to identify the key determinants of unhealthy aging in Hungary, with a particular focus on dietary patterns. Given the promising protective effects of the Mediterranean diet against CRC demonstrated in other populations [16, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55], there is a compelling rationale to explore whether these benefits can be replicated within the Hungarian context. Thus, this meta-analysis seeks to synthesize the available data on the association between the Mediterranean diet and CRC risk reduction, providing a solid scientific foundation to inform the design and implementation of dietary interventions under the Semmelweis Study framework. The ultimate goal is to leverage the insights gained to promote the Mediterranean diet as a viable strategy to address the unfavorable epidemiological trends observed in Hungary, potentially paving the way for significant public health improvements.

Methods

Literature screening

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, ClinicalTrials.gov, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and the Web of Science databases to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and human clinical trials from 2008 to 2024. The search utilized specialized and MESH (Medical Subject Headings) keywords, including “Mediterranean diet,” “Mediterranean,” “colorectal,” “rectal,” “colon,” “tumor,” “carcinoma,” “cancer,” “neoplasm,” and “risk.” Language restrictions were not imposed. The search terms were combined using the conjunctions “AND” or “OR.” Duplicate articles were identified and removed based on indexing, following which titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Articles not meeting the inclusion criteria, including those related to cancer mortality, benign adenoma, adenoma recurrence, benign polyp, and cancer survivor follow-up, were excluded. Selected articles underwent a thorough evaluation based on their full texts. The study selection process is depicted in Fig. 1.

Determining the overall effect

Statistical analysis was performed using the https://metaanalysisonline.com web application. The random effects model was employed to estimate the pooled hazard rates (HRs) and odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Forest plots were drawn to visualize the individual studies as well as the summary results. Heterogeneity of the included studies was assessed by the chi-square test and I2 index. The forest plot concisely presents data from separate studies, offering a graphical depiction of the variability within the research and showcasing the projected overall effect.

A funnel plot was utilized to explore the correlation between the estimated effects from each study and the precision of those estimates. The funnel plots were drawn to analyze publication bias. Egger’s test was computed to estimate significance.

Determining sample size robustness

We also performed a trial sequential analysis (TSA) for the a priori information size (APIS) under a risk ratio reduction of 15% with two-sided α = 5% and 1 – β = 80% power [56]. TSA analyses were done in Stata 14.1 using the metacoumbounds package. A Z-score plot was drawn to visualize the correlation between the aggregate sample size, time, and the cumulative Z-scores. The TSA analysis was performed for assessing whether the cumulative sample size is adequate to draw a conclusive inference or if further studies are required.

Subcohort analysis settings

Each step of the entire statistical analysis was performed in four settings: a combined analysis was made using the aggregate of all studies, an analysis was made using only results obtained in men and women, and finally, a separate analysis was made for case–control studies—e.g., where individuals with a CRC (cases) are compared with individuals without the CRC (controls).

Results

Combined analysis

Altogether, 26 studies were identified, of which 15 studies were synthesized in the combined setting. Based on the analysis performed using the random effects model with inverse variance method to compare the HR, there is a statistical difference, and the summarized HR is 0.84 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.78–0.91. The test for overall effect shows a significance below 0.01. There is a significant heterogeneity among the study results with an I2 value of 76%. Overall, this indicates that a Mediterranean-style diet can reduce colorectal cancer incidence by 16%.

The funnel plot for the combined analysis indicates a potential publication bias. The Eggers’ test supports the presence of funnel plot asymmetry (intercept − 2.06, 95% CI − 3.6 to − 0.53, t − 2.644, p-value 0.02). Notably, smaller studies seem to overestimate the protective effects of the Mediterranean diet.

With a relative risk reduction of 15% and an alpha of 5%, the Z-score plot indicated that the APIS was at 119,390 samples. The actual size of the combined cohorts includes 2,196,631 samples. This indicates that the combined dataset is highly robust and further studies are unlikely to change the study results.

Each of the plots for the combined analysis is provided in Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis results of assessing the correlation between a Mediterranean-style diet and colorectal cancer prevalence for the combined cohort for all available studies including a forest plot (A), a funnel plot (B), and a Z-score plot (C). SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; HR, hazard rate; APIS, a priori information size; AIS, actual information size; RRR, relative risk ratio

Male and female cohort analysis

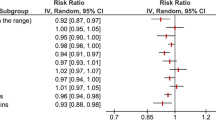

We next performed the analysis separately for the available male and female cohorts. In the male cohort, all together six studies were analyzed. Utilizing a random-effects model with the inverse variance method to compare the hazard rates, we identified a statistically significant difference. The summarized hazard rate was 0.85 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.75 to 0.97, and the test for overall effect was significant (p = 0.01). Examination of the funnel plot for these male cohorts suggested no potential publication bias, corroborated by Eggers’ test which did not indicate funnel plot asymmetry (intercept − 0.57, 95% CI − 5.14 to 3.99, t − 0.246, p-value 0.818). The Z-score plot yielded an APIS of 203,459, significantly lower than the threshold of 640,826, indicating that the data from these male cohorts is sufficient for robust conclusions. Detailed results for the male cohort analysis are presented in Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis results assessing the correlation between a Mediterranean-style diet and colorectal cancer prevalence in males only for the combined cohort for all available studies including a forest plot (A), a funnel plot (B), and a Z-score plot (C). SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; HR, hazard rate; APIS, a priori information size; AIS, actual information size; RRR, relative risk ratio

In the female cohort, a total of six studies were analyzed. Based on the analysis performed using the random effects model with inverse variance method to compare the hazard rate, there is a statistical difference, and the summarized hazard rate is 0.88 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.79–0.99. The test for overall effect is significant with p = 0.03. The funnel plot does not indicate a potential publication bias. The Eggers’ test does not support the presence of funnel plot asymmetry (intercept − 3.41, 95% CI − 6.31 to − 0.51, t − 2.302, p-value 0.083). The planned statistical threshold as presented in a Z-score plot had an APIS of 119,380 which is less than a quarter of the real value of 831,332 indicating a sufficient number of cases for concluding. The analysis results using all data gathered from females are provided in Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis results assessing the correlation between a Mediterranean-style diet and colorectal cancer prevalence in females only for the combined cohort for all available studies including a forest plot (A), a funnel plot (B), and a Z-score plot (C). SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; HR, hazard rate; APIS, a priori information size; AIS, actual information size; RRR, relative risk ratio

Case–control

In the last analysis, we compared those studies where individuals with a CRC were compared to individuals without CRC (case–control studies). In this setting, all together nine studies were analyzed. Based on the analysis performed using a random effects model with inverse variance method to compare the hazard rate, there was a statistical difference, and the summarized hazard rate was 0.51 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.38–0.68. The test for overall effect delivered a significance with a p < 0.01. There is a substantial heterogeneity among the study results with an I2 value of 89%. The funnel plot indicates a potential publication bias. The Eggers’ test supports the presence of funnel plot asymmetry (intercept − 3.12, 95% CI − 4.43 to − 1.8, t − 4.64, p-value 0.002).

The intended statistical threshold depicted in a Z-score plot shows an APIS of 3411, substantially below the actual value of 20,773, suggesting an ample number of cases for conclusive inference. Figure 5 illustrates the analysis outcomes utilizing all data collected from the case–control studies.

Meta-analysis results assessing case–control studies for evaluating the correlation between a Mediterranean-style diet and colorectal cancer with all available studies including a forest plot (A), a funnel plot (B), and a Z-score plot (C). SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; HR, hazard rate; APIS, a priori information size; AIS, actual information size; RRR, relative risk ratio

Discussion

This meta-analysis has demonstrated that high adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer, confirming the role of the Mediterranean diet as a key preventative strategy against this disease. The pooled relative risk suggests a 15 to 49% reduction in CRC risk for individuals adhering closely to Mediterranean dietary patterns. These results align with existing literature [16, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55], underscoring the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties of the Mediterranean diet, which likely contribute to its protective effects against cancer formation. For example, a similar protective effect was observed in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study, which highlighted dietary fibers and polyphenols in the Mediterranean diet as significant protective factors against CRC [39, 50]. The findings are consistent with previous studies that have identified the Mediterranean diet as beneficial in reducing the incidence of various chronic diseases, including other types of cancers and cardiovascular diseases [23,24,25,26,27,28, 57, 58].

The Mediterranean diet is thought to confer protection against cancer through several cellular and molecular mechanisms that modulate the aging process. Key components of the Mediterranean diet, such as polyphenols [59] and fibers [60], play pivotal roles in these protective mechanisms. Polyphenols, abundant in olive oil [61,62,63,64,65], nuts, and red wine, are known for their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Many of them activate sirtuins [66,67,68], including SIRT1, a protein that has been linked to longevity and epigenetic rejuvenation. SIRT1 is a histone deacetylase that influences DNA repair, mitochondrial function, inflammatory pathways, and gene expression related to aging and cancer, potentially delaying the onset of age-related diseases including CRC [69, 70].

Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet are crucial, as chronic inflammation is a known risk factor for CRC [14, 15, 41, 71]. In addition to the anti-inflammatory effects elicited by polyphenols, the high fiber content of the Mediterranean diet reduces pro-inflammatory markers and insulin resistance [72,73,74], while enhancing gut microbiota diversity [75], which in turn reduces the gut inflammation that can lead to cancerous mutations. Omega-3 fatty acids [76,77,78], predominantly from fish in the Mediterranean diet, may also contribute to reduced inflammation and inhibit the pro-inflammatory pathways involved in cancer progression.

Mitochondrial dysregulation and dysfunction are pivotal in aging and the development of age-related diseases [79,80,81,82]. As powerhouses of the cell, mitochondria are crucial for energy production, and their dysfunction leads to increased oxidative stress and impaired cellular metabolism, which contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases such as cancer [79, 83,84,85]. Components of the Mediterranean diet support mitochondrial health, including coenzyme Q10, polyphenols, and omega-3 fatty acids, which help reduce mitochondrial oxidative stress and mitochondrial DNA damage, maintain the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane, and enhance energy production efficiency [86]. Healthy mitochondria are essential for preventing oxidative stress and maintaining energy balance in cells, reducing the risk of mutations and the onset of cancer [79, 83,84,85].

Another significant mechanism through which the Mediterranean diet protects against CRC involves the reduction of oxidative stress, through the activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway [87,88,89]. Nrf2 is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of antioxidant proteins and ROS detoxifying enzymes, thereby protecting cells from oxidative macromolecular damage caused by free radicals [90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98]. Components of the Mediterranean diet can induce mild increases in ROS production, which triggers a Nrf2-mediated hormetic response that strengthens cellular defenses against more severe oxidative stress [88, 99]. This process, facilitated by phytochemicals like resveratrol from grapes and berries, enhances cellular resilience and longevity [88, 100, 101]. The resulting reduction in oxidative stress is essential for preventing oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids, which can accumulate over time and contribute to both aging and oncogenesis. Oxidative DNA damage is crucial for the induction of cellular senescence [102], and aging is associated with an increased burden of senescent cells, which support cancer development through the secretion of pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic factors known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [6, 103,104,105,106,107,108].

Autophagy is a cellular process that recycles damaged cellular components to generate energy [109, 110]. In the early stages of tumor development, autophagy acts primarily as a tumor suppressor. It helps maintain cellular homeostasis and integrity by removing damaged organelles, such as dysfunctional mitochondria, thus preventing increased mitochondrial production of ROS that are mutagenic. The Mediterranean diet, particularly when combined with time-restricted eating or intermittent fasting, may enhance autophagy, facilitating the removal of dysfunctional proteins and organelles [111,112,113].

The mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is crucial for cell growth and proliferation [114, 115]. Overactivation of this pathway is linked to aging and cancer [114]. The Mediterranean diet, through its balanced protein content and high levels of polyunsaturated fats and phytochemicals, may downregulate mTOR signaling [116], thus inhibiting cell proliferation and survival of cancerous cells.

Additional mechanisms by which the Mediterranean diet may protect against tumorigenesis include its beneficial effects on the gut microbiota, which play a crucial role in colon health and overall disease prevention [117,118,119,120]. The high fiber content of the Mediterranean diet, sourced from a variety of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, significantly alters the composition of the gut microbiota. This dietary fiber is fermented by gut bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. Among these, butyrate is particularly noteworthy for its role as a primary energy source for colonocytes and its potent anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic properties [121, 122].

Components of the Mediterranean diet may also play a role in suppressing the growth and virulence of oncogenic bacteria, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, which are implicated in the development and progression of colorectal cancer [118, 119, 123,124,125,126]. Fusobacterium spp. are known to promote tumor growth by modulating the tumor microenvironment, inducing inflammation, and interacting with cancer cells to enhance their growth and invasiveness [126,127,128,129,130,131,132]. The impact of the Mediterranean diet on reducing these harmful bacterial populations while enhancing overall microbial diversity and stability is critical.

The sex-specific analysis within this study indicated that men benefit more from the Mediterranean diet in terms of CRC risk reduction compared to women. This could be due to biological differences, such as hormonal influences that modulate diet effectiveness, or behavioral differences in diet adherence [133,134,135,136,137,138]. Future research should focus on understanding these mechanisms and exploring whether dietary recommendations should be adjusted to maximize efficacy in each sex.

One of the strengths of this meta-analysis is its large sample size and the inclusion of studies from diverse geographical locations, enhancing the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the robustness of the results was confirmed through rigorous sensitivity analyses, indicating that the observed associations are stable across various study designs and populations. However, the study is not without limitations. Despite adjusting for major confounders, residual confounding cannot be entirely ruled out. Dietary self-reporting, which is prone to measurement errors, was used in the original studies, potentially leading to misclassification of dietary adherence. The moderate heterogeneity observed in our meta-analysis indicates substantial variability in how the Mediterranean diet is defined and measured across different studies. This variability likely arises from a combination of factors, including diverse dietary assessment methods, regional variations in dietary practices that fall under the broad category of the Mediterranean diet, and differing baseline characteristics of the study populations, such as age, sex, and health status. These factors can significantly affect the results and interpretations of the diet’s impact on colorectal cancer risk. Understanding and addressing these sources of heterogeneity is crucial not only for accurately assessing the protective effects of the Mediterranean diet but also for refining dietary recommendations to ensure they are effectively tailored to specific demographic and regional contexts. This nuanced understanding will enhance the precision of public health strategies aimed at cancer prevention through dietary modifications.

The findings from this meta-analysis have significant implications for the Semmelweis Study, a comprehensive, prospective cohort study conducted at Semmelweis University [8]. The unhealthy aging of the Hungarian population is likely influenced by a complex interplay of factors, not all of which are fully understood. Behavioral risk factors such as low physical activity, obesity, and unhealthy diet are particularly prevalent in Hungary, accounting for half of all deaths, a rate significantly higher than the European Union average of 39% [139]. The Semmelweis Study aims to dissect the multifaceted influences of lifestyle factors on the unsuccessful aging process and the progression of chronic age-associated diseases within the Hungarian population [8]. A primary component of the Semmelweis Study’s baseline data collection includes a comprehensive questionnaire with a health determinants module that collects detailed data on dietary habits among participants [8]. This data collection is crucial as it directly connects with the substantial benefits observed from the Mediterranean diet in mitigating risk factors associated with aging and chronic diseases, such as CRC and cardiovascular disease. The findings of the present meta-analysis align closely with the study’s objectives to explore how dietary patterns influence health outcomes in the aging Hungarian population. Integrating detailed assessments of dietary adherence into the study’s initial and subsequent data collection phases will allow the investigative team to more effectively gauge the impact of diet on aging and disease outcomes. This methodological approach not only facilitates the identification of significant correlations but also supports the exploration of causal relationships through detailed longitudinal analysis. By doing so, the study can offer valuable insights into how dietary factors contribute to successful or unsuccessful aging, informing targeted interventions and public health strategies aimed at improving the well-being of the Hungarian population. Investigating how the Mediterranean diet’s impact varies between male and female employees could uncover important biological or behavioral factors that influence dietary effectiveness. Another intriguing aspect for exploration is the interplay between lifestyle factors such as diet and the occupational and environmental conditions encountered by the university’s employees. Understanding how these factors collectively impact aging and health outcomes is crucial. For instance, the study could examine whether certain occupational stressors or environmental exposures at the university amplify the effects of the diet or perhaps obscure its benefits. Additionally, understanding how the Mediterranean diet interacts with lifestyle variables like physical activity levels, smoking, and alcohol consumption could provide a holistic view of its role in promoting health and longevity in the workplace.

To further enhance our understanding, embedded studies within the Semmelweis Study are being meticulously designed to specifically explore the impact of the Mediterranean diet within the Hungarian context. These embedded studies aim to assess dietary adherence and examine specific components of the Mediterranean diet [140,141,142,143,144] such as the intake of olive oil, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes. Additionally, pilot interventional studies are planned where subsets of participants are encouraged to adopt a Mediterranean diet. These trials will monitor changes in health indicators to longitudinally assess the diet’s efficacy. Studies will consider the socioeconomic and cultural factors that may facilitate or hinder the adoption of the Mediterranean diet among Hungarians. This aspect is crucial for tailoring dietary recommendations that are feasible and effective within the local context. By incorporating these targeted studies, the Semmelweis University initiative not only aligns with global health strategies but also pioneers a region-specific approach to combating age-related diseases through dietary interventions. This strategic focus on the Mediterranean diet could lead to significant public health benefits, providing a model for similar interventions in other populations facing comparable health challenges.

The enhanced focus on the Mediterranean diet within the Semmelweis Study has the potential to shape targeted dietary interventions that could substantially decrease the incidence of age-related diseases among the university’s employees. Moreover, by pinpointing the dietary factors that differentiate successful from unsuccessful aging, the study could yield vital insights that enhance public health strategies, not only for the university community but also for the broader population. The demonstration of the Mediterranean diet’s protective role against CRC carries profound implications for public health, especially in Hungary, where rates of CRC morbidity and mortality are alarmingly high. The adoption and promotion of the Mediterranean diet could become a cornerstone of national cancer prevention strategies. This dietary approach not only aligns with global health recommendations but also offers a culturally adaptable model for improving health outcomes through nutrition. Thus, the insights gained from the Semmelweis Study could inform broader dietary guidelines and public health policies aimed at combating one of the most prevalent cancers in Hungary.

References

Hu S, Li Y, Zhu W, Liu J, Wei S. Global, region and national trends and age-period-cohort effects in colorectal cancer burden from 1990 to 2019, with predictions to 2039. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30:83245–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28223-3.

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72:338–44. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327736.

Sharma R. A comparative examination of colorectal cancer burden in European Union, 1990–2019: estimates from Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27:1309–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-022-02182-0.

GBD. Colorectal Cancer Collaborators: Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;2022(7):627–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00044-9.

Fekete M, Major D, Feher A, Fazekas-Pongor V, Lehoczki A. Geroscience and pathology: a new frontier in understanding age-related diseases. Pathol Oncol Res. 2024;30:1611623. https://doi.org/10.3389/pore.2024.1611623.

Ungvari Z, Ungvari A, Bianchini G, Gyorffy B. Prognostic significance of a signature based on senescence-related genes in colorectal cancer. Geroscience. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01164-6.

Kovacs N, Piko P, Juhasz A, Nagy C, Oroszi B, Ungvari Z, Adany R. Comparative analysis of health status and health service utilization patterns among rural and urban elderly populations in Hungary: a study on the challenges of unhealthy aging. Geroscience. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00926-y.

Ungvari Z, Tabak AG, Adany R, Purebl G, Kaposvari C, Fazekas-Pongor V, Csipo T, Szarvas Z, Horvath K, Mukli P, et al. The Semmelweis Study: a longitudinal occupational cohort study within the framework of the Semmelweis Caring University Model Program for supporting healthy aging. Geroscience. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-01018-7.

Bardos H, Llanaj E, Vincze F, Dioszegi J, Piko P, Kosa Z, Sandor J, Adany R. Diet quality as assessed by Healthy Eating Index-2015 among Hungarian Roma living in settlements of Northeast Hungary. Sci Rep. 2022;12:19213. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23670-3.

Llanaj E, Vincze F, Kosa Z, Bardos H, Dioszegi J, Sandor J, Adany R. Deteriorated dietary patterns with regards to health and environmental sustainability among Hungarian Roma are not differentiated from those of the general population. Nutrients. 2021;13:721. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030721.

Soos R, Bako C, Gyebrovszki A, Gordos M, Csala D, Adam Z, Wilhelm M. Nutritional habits of Hungarian older adults. Nutrients. 2024;16:1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16081203.

Erdei G, Kovacs VA, Bakacs M, Martos E. Hungarian Diet and Nutritional Status Survey 2014. I. Nutritional status of the Hungarian adult population. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:533–40. https://doi.org/10.1556/650.2017.30700.

Sarkadi Nagy E, Bakacs M, Illes E, Nagy B, Varga A, Kis O, Schreiberne Molnar E, Martos E. Hungarian Diet and Nutritional Status Survey - OTAP2014. II. Energy and macronutrient intake of the Hungarian population. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:587–97. https://doi.org/10.1556/650.2017.30718.

Shivappa N, Godos J, Hebert JR, Wirth MD, Piuri G, Speciani AF, Grosso G. Dietary Inflammatory index and colorectal cancer risk-a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9091043.

Nolfo F, Rametta S, Marventano S, Grosso G, Mistretta A, Drago F, Gangi S, Basile F, Biondi A. Pharmacological and dietary prevention for colorectal cancer. BMC Surg. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S16.

Grosso G, Biondi A, Galvano F, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Buscemi S, Drago F, Basile F. Factors associated with colorectal cancer in the context of the Mediterranean diet: a case-control study. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:558–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2014.902975.

Godos J, Bella F, Sciacca S, Galvano F, Grosso G. Vegetarianism and breast, colorectal and prostate cancer risk: an overview and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30:349–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12426.

Yang X, Wu D, Liu Y, He Z, Manyande A, Fu H, Xiang H. Global disease burden linked to diet high in red meat and colorectal cancer from 1990 to 2019 and its prediction up to 2030. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1366553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1366553.

Liang Y, Zhang N, Wang M, Liu Y, Ma L, Wang Q, Yang Q, Liu X, Zhou F, Wei Y. Distributions and trends of the global burden of colorectal cancer attributable to dietary risk factors over the past 30 years. Nutrients. 2023;16:132. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010132.

Godos J, Scazzina F, Paterno Castello C, Giampieri F, Quiles JL, Briones Urbano M, Battino M, Galvano F, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G, et al. Underrated aspects of a true Mediterranean diet: understanding traditional features for worldwide application of a “Planeterranean” diet. J Transl Med. 2024;22:294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05095-w.

Nucci D, Nardi M, Cinnirella A, Campagnoli E, Maffeo M, Perrone PM, Shishmintseva V, Grosso FM, Castrofino A, Castaldi S, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of pancreatic cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032403.

Marventano S, Godos J, Platania A, Galvano F, Mistretta A, Grosso G. Mediterranean diet adherence in the Mediterranean healthy eating, aging and lifestyle (MEAL) study cohort. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2018;69:100–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2017.1332170.

Grosso G, Stepaniak U, Micek A, Topor-Madry R, Stefler D, Szafraniec K, Bobak M, Pajak A. A Mediterranean-type diet is associated with better metabolic profile in urban Polish adults: results from the HAPIEE study. Metabolism. 2015;64:738–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2015.02.007.

Grosso G, Pajak A, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Raciti T, Buscemi S, Drago F, Scalfi L, Galvano F. Protective role of the Mediterranean diet on several cardiovascular risk factors: evidence from Sicily, southern Italy. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:370–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2013.09.020.

Grosso G, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Purrello A, Vitaglione P, Calabrese G, Drago F, Galvano F. Beneficial effects of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:5039–44. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612819666131206112144.

Grosso G, Mistretta A, Frigiola A, Gruttadauria S, Biondi A, Basile F, Vitaglione P, D’Orazio N, Galvano F. Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54:593–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2011.596955.

Grosso G, Marventano S, Yang J, Micek A, Pajak A, Scalfi L, Galvano F, Kales SN. A comprehensive meta-analysis on evidence of Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease: are individual components equal? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:3218–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2015.1107021.

Grosso G, Buscemi S, Galvano F, Mistretta A, Marventano S, La Vela V, Drago F, Gangi S, Basile F, Biondi A. Mediterranean diet and cancer: epidemiological evidence and mechanism of selected aspects. BMC Surg. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S14.

Damigou E, Faka A, Kouvari M, Anastasiou C, Kosti RI, Chalkias C, Panagiotakos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean type of diet in the world: a geographical analysis based on a systematic review of 57 studies with 1,125,560 participants. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2023;74:799–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2023.2262781.

Godos J. Decreasing adherence to the Mediterranean diet: health and environmental foe. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2023;74:797–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2023.2290439.

Jafari Nasab S, Clark CCT, Entezari M. Mediterranean diet and colorectal adenomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2024;33:223–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000861.

Fliss-Isakov N, Kariv R, Webb M, Ivancovsky D, Margalit D, Zelber-Sagi S. Mediterranean dietary components are inversely associated with advanced colorectal polyps: a case-control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2617–27. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i24.2617.

Whalen KA, McCullough M, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Judd S, Bostick RM. Paleolithic and Mediterranean diet pattern scores and risk of incident, sporadic colorectal adenomas. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:1088–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwu235.

Rosato V, Guercio V, Bosetti C, Negri E, Serraino D, Giacosa A, Montella M, La Vecchia C, Tavani A. Mediterranean diet and colorectal cancer risk: a pooled analysis of three Italian case-control studies. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:862–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.245.

Kontou N, Psaltopoulou T, Soupos N, Polychronopoulos E, Xinopoulos D, Linos A, Panagiotakos DB. Metabolic syndrome and colorectal cancer: the protective role of Mediterranean diet–a case-control study. Angiology. 2012;63:390–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319711421164.

Schulpen M, van den Brandt PA. Mediterranean diet adherence and risk of colorectal cancer: the prospective Netherlands Cohort Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00549-8.

Park SY, Boushey CJ, Wilkens LR, Haiman CA, Le Marchand L. High-quality diets associate with reduced risk of colorectal cancer: analyses of diet quality indexes in the multiethnic cohort. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(386–394):e382. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.004.

Shang X, Liu J, Zhu Z, Zhang X, Huang Y, Liu S, Wang W, Zhang X, Tang S, Hu Y, et al. Healthy dietary patterns and the risk of individual chronic diseases in community-dwelling adults. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6704. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42523-9.

Castello A, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Fernandez de Larrea N, Jakszyn P, Dorronsoro A, Amiano P, Chirlaque MD, Colorado-Yohar S, Guevara M, Moreno-Iribas C, et al. Adherence to the western, prudent and Mediterranean dietary patterns and colorectal cancer risk: findings from the Spanish cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Spain). Nutrients. 2022;14:3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153085.

Zheng X, Hur J, Nguyen LH, Liu J, Song M, Wu K, Smith-Warner SA, Ogino S, Willett WC, Chan AT, et al. Comprehensive assessment of diet quality and risk of precursors of early-onset colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:543–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa164.

Boden S, Myte R, Wennberg M, Harlid S, Johansson I, Shivappa N, Hebert JR, Van Guelpen B, Nilsson LM. The inflammatory potential of diet in determining cancer risk; a prospective investigation of two dietary pattern scores. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0214551. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214551.

Cheng E, Um CY, Prizment AE, Lazovich D, Bostick RM. Evolutionary-concordance lifestyle and diet and mediterranean diet pattern scores and risk of incident colorectal cancer in Iowa women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27:1195–202. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1184.

Lavalette C, Adjibade M, Srour B, Sellem L, Fiolet T, Hercberg S, Latino-Martel P, Fassier P, Deschasaux M, Kesse-Guyot E, Touvier M. Cancer-specific and general nutritional scores and cancer risk: results from the prospective NutriNet-Sante cohort. Cancer Res. 2018;78:4427–35. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0155.

Petimar J, Smith-Warner SA, Fung TT, Rosner B, Chan AT, Hu FB, Giovannucci EL, Tabung FK. Recommendation-based dietary indexes and risk of colorectal cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:1092–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy171.

Torres Stone RA, Waring ME, Cutrona SL, Kiefe CI, Allison J, Doubeni CA. The association of dietary quality with colorectal cancer among normal weight, overweight and obese men and women: a prospective longitudinal study in the USA. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015619. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015619.

Jones P, Cade JE, Evans CEL, Hancock N, Greenwood DC. The Mediterranean diet and risk of colorectal cancer in the UK Women’s Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1786–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx155.

Vargas AJ, Neuhouser ML, George SM, Thomson CA, Ho GY, Rohan TE, Kato I, Nassir R, Hou L, Manson JE. Diet quality and colorectal cancer risk in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv304.

Sieri S, Agnoli C, Pala V, Grioni S, Brighenti F, Pellegrini N, Masala G, Palli D, Mattiello A, Panico S, et al. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and cancer risk: results from the EPIC-Italy study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9757. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09498-2.

Bamia C, Lagiou P, Buckland G, Grioni S, Agnoli C, Taylor AJ, Dahm CC, Overvad K, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, et al. Mediterranean diet and colorectal cancer risk: results from a European cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:317–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-013-9795-x.

Agnoli C, Grioni S, Sieri S, Palli D, Masala G, Sacerdote C, Vineis P, Tumino R, Giurdanella MC, Pala V, et al. Italian Mediterranean Index and risk of colorectal cancer in the Italian section of the EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1404–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27740.

Fung TT, Hu FB, Wu K, Chiuve SE, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. The Mediterranean and dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diets and colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1429–35. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29242.

Reedy J, Mitrou PN, Krebs-Smith SM, Wirfalt E, Flood A, Kipnis V, Leitzmann M, Mouw T, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A, Subar AF. Index-based dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer: the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:38–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn097.

Bujanda-Miguel G, Martinez-Roca A, Garcia-Heredia A, Guill-Berbegal D, Roche E, Jover R. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and its association with multiple colonic polyps of unknown origin: a case-control study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1186808. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1186808.

Alegria-Lertxundi I, Aguirre C, Bujanda L, Fernandez FJ, Polo F, Ordovas JM, Etxezarraga MC, Zabalza I, Larzabal M, Portillo I, et al. Food groups, diet quality and colorectal cancer risk in the Basque Country. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:4108–25. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i28.4108.

GBD. Colorectal Cancer Collaborators: the global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2019(4):913–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30345-0.

Miladinovic B, Hozo I, Djulbegovic B. Trial sequential boundaries for cumulative meta-analyses. Stata J. 2013;13:77–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x1301300106.

Godos J, Grosso G, Ferri R, Caraci F, Lanza G, Al-Qahtani WH, Caruso G, Castellano S. Mediterranean diet, mental health, cognitive status, quality of life, and successful aging in southern Italian older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2023;175:112143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2023.112143.

Godos J, Ferri R, Lanza G, Caraci F, Vistorte AOR, Yelamos Torres V, Grosso G, Castellano S. Mediterranean diet and sleep features: a systematic review of current evidence. Nutrients. 2024;16:282. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16020282.

Zamora-Ros R, Cayssials V, Jenab M, Rothwell JA, Fedirko V, Aleksandrova K, Tjonneland A, Kyro C, Overvad K, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Dietary intake of total polyphenol and polyphenol classes and the risk of colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:1063–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0408-6.

Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, Norat T. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2011;343:d6617. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d6617.

Wise J. Reduced breast cancer risk seen with Mediterranean diet and added olive oil. BMJ. 2015;351:h4911. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4911.

Romanos-Nanclares A, Guasch-Ferre M, Willett WC, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Rosner BA, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Eliassen AH. Consumption of olive oil and risk of breast cancer in U.S. women: results from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Br J Cancer. 2023;129:416–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-023-02306-x.

Pelucchi C, Bosetti C, Negri E, Lipworth L, La Vecchia C. Olive oil and cancer risk: an update of epidemiological findings through 2010. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:805–12. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161211795428920.

Markellos C, Ourailidou ME, Gavriatopoulou M, Halvatsiotis P, Sergentanis TN, Psaltopoulou T. Olive oil intake and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0261649. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261649.

Filik L, Ozyilkan O. Olive-oil consumption and cancer risk. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:191. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601497.

Tatar M, Varedi M, Naghibalhossaini F. Epigenetic effects of blackberry extract on human colorectal cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 2022;74:1446–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2021.1952454.

Buhrmann C, Shayan P, Popper B, Goel A, Shakibaei M. Sirt1 is required for resveratrol-mediated chemopreventive effects in colorectal cancer cells. Nutrients. 2016;8:145. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8030145.

Chen L, Li M, Zhou H, Liu Y, Pang W, Ma T, Niu C, Yang Z, Chang AK, Li X, Bi X. Sirtuin1 (SIRT1) is involved in the anticancer effect of black raspberry anthocyanins in colorectal cancer. Eur J Nutr. 2023;62:395–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-022-02989-7.

Yuan Y, Cruzat VF, Newsholme P, Cheng J, Chen Y, Lu Y. Regulation of SIRT1 in aging: roles in mitochondrial function and biogenesis. Mech Ageing Dev. 2016;155:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2016.02.003.

Imai SI, The NAD. World 2.0: the importance of the inter-tissue communication mediated by NAMPT/NAD(+)/SIRT1 in mammalian aging and longevity control. NPJ Syst Biol Appl. 2016;2:16018. https://doi.org/10.1038/npjsba.2016.18.

Rafiee P, Shivappa N, Hebert JR, Nasab SJ, Bahrami A, Hekmatdoost A, Rashidkhani B, Sadeghi A, Houshyari M, Hejazi E. Dietary inflammatory index and odds of colorectal cancer and colorectal adenomatous polyps in a case-control study from Iran. Nutrients. 2019;11:1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061213.

Weickert MO, Pfeiffer AFH. Impact of dietary fiber consumption on insulin resistance and the prevention of type 2 diabetes. J Nutr. 2018;148:7–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxx008.

Tucker LA. Fiber intake and insulin resistance in 6374 adults: the role of abdominal obesity. Nutrients. 2018;10:237. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020237.

Niero M, Bartoli G, De Colle P, Scarcella M, Zanetti M. Impact of dietary fiber on inflammation and insulin resistance in older patients: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2023;15:2365. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102365.

Kuo SM. Does modification of the large intestinal microbiome contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity of fermentable fiber? Curr Dev Nutr. 2018;2:nzx004. https://doi.org/10.3945/cdn.117.001180.

Song M, Lee IM, Manson JE, Buring JE, Dushkes R, Gordon D, Walter J, Wu K, Chan AT, Ogino S, et al. Effect of supplementation with marine omega-3 fatty acid on risk of colorectal adenomas and serrated polyps in the US general population: a prespecified ancillary study of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:108–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.4587.

Wang T, Brown NM, McCoy AN, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, gut microbiota, microbial metabolites, and risk of colorectal adenomas. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14184443.

Shin A, Cho S, Sandin S, Lof M, Oh MY, Weiderpass E. Omega-3 and -6 fatty acid intake and colorectal cancer risk in Swedish women’s lifestyle and health cohort. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52:848–54. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2019.550.

Harrington JS, Ryter SW, Plataki M, Price DR, Choi AMK. Mitochondria in health, disease, and aging. Physiol Rev. 2023;103:2349–422. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00058.2021.

Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Sorond F, Merkely B, Csiszar A. Mechanisms of vascular aging, a geroscience perspective: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:931–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.061.

Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Donato AJ, Galvan V, Csiszar A. Mechanisms of vascular aging. Circ Res. 2018;123:849–67. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311378.

Dai DF, Rabinovitch PS, Ungvari Z. Mitochondria and cardiovascular aging. Circ Res. 2012;110:1109–24. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246140110/8/1109[pii].

Patel J, Baptiste BA, Kim E, Hussain M, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. DNA damage and mitochondria in cancer and aging. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:1625–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgaa114.

Zinovkin RA, Lyamzaev KG, Chernyak BV. Current perspectives of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants in cancer prevention and treatment. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1048177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2023.1048177.

Kenny TC, Birsoy K. Mitochondria and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a041534.

Pollicino F, Veronese N, Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M. Mediterranean diet and mitochondria: new findings. Exp Gerontol. 2023;176:112165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2023.112165.

Yubero-Serrano EM, Gonzalez-Guardia L, Rangel-Zuniga O, Delgado-Casado N, Delgado-Lista J, Perez-Martinez P, Garcia-Rios A, Caballero J, Marin C, Gutierrez-Mariscal FM, et al. Postprandial antioxidant gene expression is modified by Mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme Q(10) in elderly men and women. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:159–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-011-9331-4.

Martucci M, Ostan R, Biondi F, Bellavista E, Fabbri C, Bertarelli C, Salvioli S, Capri M, Franceschi C, Santoro A. Mediterranean diet and inflammaging within the hormesis paradigm. Nutr Rev. 2017;75:442–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nux013.

Gonzalez-Guardia L, Yubero-Serrano EM, Delgado-Lista J, Perez-Martinez P, Garcia-Rios A, Marin C, Camargo A, Delgado-Casado N, Roche HM, Perez-Jimenez F, et al. Effects of the Mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme q10 on metabolomic profiles in elderly men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:78–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu098.

Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Nyul-Toth A, Kiss T, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Balasubramanian P, Lipecz A, Benyo Z, Csiszar A. Nrf2 dysfunction and impaired cellular resilience to oxidative stressors in the aged vasculature: from increased cellular senescence to the pathogenesis of age-related vascular diseases. Geroscience. 2019;41:727–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-019-00107-w.

Ungvari Z, Bailey-Downs L, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Koncz P, Losonczy G, Ballabh P, de Cabo R, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A. Vascular oxidative stress in aging: a homeostatic failure due to dysregulation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H363-372.

Ungvari Z, Bailey-Downs L, Gautam T, Sosnowska D, Wang M, Monticone RE, Telljohann R, Pinto JT, de Cabo R, Sonntag WE, et al. Age-associated vascular oxidative stress, Nrf2 dysfunction and NF-kB activation in the non-human primate Macaca mulatta. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:866–75.

Tarantini S, Valcarcel-Ares MN, Yabluchanskiy A, Tucsek Z, Hertelendy P, Kiss T, Gautam T, Zhang XA, Sonntag WE, de Cabo R, et al. Nrf2 deficiency exacerbates obesity-induced oxidative stress, neurovascular dysfunction, blood brain barrier disruption, neuroinflammation, amyloidogenic gene expression and cognitive decline in mice, mimicking the aging phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:853–63.

Pearson KJ, Lewis KN, Price NL, Chang JW, Perez E, Cascajo MV, Tamashiro KL, Poosala S, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, et al. Nrf2 mediates cancer protection but not prolongevity induced by caloric restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2325–30.

Fulop GA, Kiss T, Tarantini S, Balasubramanian P, Yabluchanskiy A, Farkas E, Bari F, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A. Nrf2 deficiency in aged mice exacerbates cellular senescence promoting cerebrovascular inflammation. Geroscience. 2018;40:513–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-018-0047-6.

Csiszar A, Pinto JT, Gautam T, Kleusch C, Hoffmann B, Tucsek Z, Toth P, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z. Resveratrol encapsulated in novel fusogenic liposomes activates Nrf2 and attenuates oxidative stress in cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells from aged rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;70(3):303–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu029.

Csiszar A, Gautam T, Sosnowska D, Tarantini S, Banki E, Tucsek Z, Toth P, Losonczy G, Koller A, Reglodi D, et al. Caloric restriction confers persistent anti-oxidative, pro-angiogenic, and anti-inflammatory effects and promotes anti-aging miRNA expression profile in cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells of aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H292-306. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00307.2014.

Angelone T, Rocca C, Lionetti V, Penna C, Pagliaro P. Expanding the Frontiers of guardian antioxidant selenoproteins in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2024;40:369–432. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2023.0285.

Ali S, Davinelli S, Accardi G, Aiello A, Caruso C, Duro G, Ligotti ME, Pojero F, Scapagnini G, Candore G. Healthy ageing and Mediterranean diet: a focus on hormetic phytochemicals. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021;200:111592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2021.111592.

Santoro A, Martucci M, Conte M, Capri M, Franceschi C, Salvioli S. Inflammaging, hormesis and the rationale for anti-aging strategies. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;64:101142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101142.

Calabrese EJ, Nascarella M, Pressman P, Hayes AW, Dhawan G, Kapoor R, Calabrese V, Agathokleous E. Hormesis determines lifespan. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;94:102181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102181.

Yuan H, Xu Y, Luo Y, Wang NX, Xiao JH. Role of Nrf2 in cell senescence regulation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476:247–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-020-03901-9.

Haston S, Gonzalez-Gualda E, Morsli S, Ge J, Reen V, Calderwood A, Moutsopoulos I, Panousopoulos L, Deletic P, Carreno G, et al. Clearance of senescent macrophages ameliorates tumorigenesis in KRAS-driven lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1242–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2023.05.004.

Wyld L, Bellantuono I, Tchkonia T, Morgan J, Turner O, Foss F, George J, Danson S, Kirkland JL. Senescence and cancer: a review of clinical implications of senescence and senotherapies. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082134.

Lecot P, Alimirah F, Desprez PY, Campisi J, Wiley C. Context-dependent effects of cellular senescence in cancer development. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:1180–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.115bjc2016115[pii].

Laberge RM, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, Patil CK, Freund A, Zhou L, Curran SC, Davalos AR, Wilson-Edell KA, Liu S, et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1049–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3195.

Krtolica A, Parrinello S, Lockett S, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: a link between cancer and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12072–7.

Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685–705. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653.

Tabibzadeh S. Role of autophagy in aging: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Aging Cell. 2023;22:e13753. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13753.

Aman Y, Schmauck-Medina T, Hansen M, Morimoto RI, Simon AK, Bjedov I, Palikaras K, Simonsen A, Johansen T, Tavernarakis N, et al. Autophagy in healthy aging and disease. Nat Aging. 2021;1:634–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-021-00098-4.

Yin Z, Klionsky DJ. Intermittent time-restricted feeding promotes longevity through circadian autophagy. Autophagy. 2022;18:471–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2022.2039524.

Mishra S, Persons PA, Lorenzo AM, Chaliki SS, Bersoux S. Time-restricted eating and its metabolic benefits. J Clin Med. 2023;12:7007. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12227007.

Long H, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding and circadian autophagy for long life. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18:5–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00600-3.

Sharp ZD, Richardson A. Aging and cancer: can mTOR inhibitors kill two birds with one drug? Target Oncol. 2011;6:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-011-0168-7.

Fernandes SA, Demetriades C. The multifaceted role of nutrient sensing and mTORC1 signaling in physiology and aging. Front Aging. 2021;2:707372. https://doi.org/10.3389/fragi.2021.707372.

Vasto S, Buscemi S, Barera A, Di Carlo M, Accardi G, Caruso C. Mediterranean diet and healthy ageing: a Sicilian perspective. Gerontology. 2014;60:508–18. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363060.

Piazzi G, Prossomariti A, Baldassarre M, Montagna C, Vitaglione P, Fogliano V, Biagi E, Candela M, Brigidi P, Balbi T, et al. A Mediterranean diet mix has chemopreventive effects in a murine model of colorectal cancer modulating apoptosis and the gut microbiota. Front Oncol. 2019;9:140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00140.

Merra G, Noce A, Marrone G, Cintoni M, Tarsitano MG, Capacci A, De Lorenzo A. Influence of Mediterranean diet on human gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2020;13:7. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13010007.

Gundogdu A, Nalbantoglu OU. The role of the Mediterranean diet in modulating the gut microbiome: a review of current evidence. Nutrition. 2023;114: 112118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2023.112118.

Almanza-Aguilera E, Cano A, Gil-Lespinard M, Burguera N, Zamora-Ros R, Agudo A, Farras M. Mediterranean diet and olive oil, microbiota, and obesity-related cancers. From mechanisms to prevention. Semin Cancer Biol. 2023;95:103–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.08.001.

Kazmierczak-Siedlecka K, Marano L, Merola E, Roviello F, Polom K. Sodium butyrate in both prevention and supportive treatment of colorectal cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1023806. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1023806.

Karim MR, Iqbal S, Mohammad S, Morshed MN, Haque MA, Mathiyalagan R, Yang DC, Kim YJ, Song JH, Yang DU. Butyrate’s (a short-chain fatty acid) microbial synthesis, absorption, and preventive roles against colorectal and lung cancer. Arch Microbiol. 2024;206:137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-024-03834-7.

Nakanishi M, Chen Y, Qendro V, Miyamoto S, Weinstock E, Weinstock GM, Rosenberg DW. Effects of walnut consumption on colon carcinogenesis and microbial community structure. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2016;9:692–703. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0026.

Narii N, Zha L, Sobue T, Kitamura T, Shiba S, Mizutani S, Yamada T, Yachida S. Association between diet and Fusobacterium nucleatum in the feces of healthy adults: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2023;16(2):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-22-0399.

Nawab S, Bao Q, Ji LH, Luo Q, Fu X, Fan S, Deng Z, Ma W. The pathogenicity of Fusobacterium nucleatum modulated by dietary fibers-a possible missing link between the dietary composition and the risk of colorectal cancer. Microorganisms. 2023;11:2004. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11082004.

Mehta RS, Nishihara R, Cao Y, Song M, Mima K, Qian ZR, Nowak JA, Kosumi K, Hamada T, Masugi Y, et al. Association of dietary patterns with risk of colorectal cancer subtypes classified by fusobacterium nucleatum in tumor tissue. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:921–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6374.

Rubinstein MR, Baik JE, Lagana SM, Han RP, Raab WJ, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Wang TC, Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer by inducing Wnt/beta-catenin modulator Annexin A1. EMBO Rep. 2019;20:e47638. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201847638.

Hashemi Goradel N, Heidarzadeh S, Jahangiri S, Farhood B, Mortezaee K, Khanlarkhani N, Negahdari B. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: a mechanistic overview. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:2337–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27250.

Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Cao Y, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Yang J, Dou R, Masugi Y, Song M, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut. 2016;65:1973–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310101.

Borowsky J, Haruki K, Lau MC, Dias Costa A, Vayrynen JP, Ugai T, Arima K, da Silva A, Felt KD, Zhao M, et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with specific T-cell subsets in the colorectal carcinoma microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:2816–26. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4009.

Wu Z, Ma Q, Guo Y, You F. The role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5350. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215350.

Brennan CA, Garrett WS. Fusobacterium nucleatum - symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:156–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0129-6.

Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Frank G, De Santis GL, Cianci R, Bigioni G, De Lorenzo A. Sex differences in the efficacy of Mediterranean diet treatment: a nutrigenomics pilot study. Genes (Basel). 2023;14:1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14111980.

Bedard A, Tchernof A, Lamarche B, Corneau L, Dodin S, Lemieux S. Effects of the traditional Mediterranean diet on adiponectin and leptin concentrations in men and premenopausal women: do sex differences exist? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:561–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.27.

Bedard A, Riverin M, Dodin S, Corneau L, Lemieux S. Sex differences in the impact of the Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular risk profile. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:1428–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114511006969.

Bedard A, Lamarche B, Corneau L, Dodin S, Lemieux S. Sex differences in the impact of the Mediterranean diet on systemic inflammation. Nutr J. 2015;14:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-015-0035-y.

Bedard A, Corneau L, Lamarche B, Dodin S, Lemieux S. Sex-related differences in the effects of the mediterranean diet on glucose and insulin homeostasis. J Nutr Metab. 2014;2014:424130. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/424130.

Barrea L, Verde L, Suarez R, Frias-Toral E, Vasquez CA, Colao A, Savastano S, Muscogiuri G. Sex-differences in Mediterranean diet: a key piece to explain sex-related cardiovascular risk in obesity? A cross-sectional study. J Transl Med. 2024;22:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04814-z.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. State of Health in the EU. Hungary: Country Health Profile 2021. In: Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1787/482f3633-en.

Svezia B, Cabiati M, Matteucci M, Passino C, Pe ME, Lionetti V, Del Ry S. Tuscany Sangiovese grape juice imparts cardioprotection by regulating gene expression of cardioprotective C-type natriuretic peptide. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59:2953–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02134-x.

Reca IB, Lionetti V, Camardella L, D’Avino R, Giardina T, Cervone F, Bellincampi D. A functional pectin methylesterase inhibitor protein (SolyPMEI) is expressed during tomato fruit ripening and interacts with PME-1. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;79:429–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-012-9921-2.

Lionetti V, Tuana BS, Casieri V, Parikh M, Pierce GN. Importance of functional food compounds in cardioprotection through action on the epigenome. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:575–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy597.

Casieri V, Matteucci M, Cavallini C, Torti M, Torelli M, Lionetti V. Long-term intake of pasta containing barley (1–3)Beta-D-glucan increases neovascularization-mediated cardioprotection through endothelial upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and Parkin. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13424. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13949-1.

Agostini S, Chiavacci E, Matteucci M, Torelli M, Pitto L, Lionetti V. Barley beta-glucan promotes MnSOD expression and enhances angiogenesis under oxidative microenvironment. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:227–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.12442.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Semmelweis University. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (RF1AG072295, R01AG055395, R01AG068295; R01AG070915), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS100782), the National Cancer Institute (R01CA255840). AU was supported by TKP2021-NKTA-47, implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA funding scheme, by funding through the National Cardiovascular Laboratory Program (RRF-2.3.1–21-2022–00003) and by the National Laboratory for Drug Research and Development (PharmaLab, RRF-2.3.1–21-2022–00015) provided by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, Project no. 135784 implemented with the support provided from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the K20 funding scheme and the European University for Well-Being (EUniWell) program (grant agreement number: 101004093/ EUniWell/EAC-A02-2019 / EAC-A02-2019–1). The 4.0 version of ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI, was used as a language tool to refine our writing, enhancing the clarity of our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Balázs Győrffy serves as Associate Editor for GeroScience. Dr. Zoltan Ungvari serves as Editor-in-Chief for GeroScience and has personal relationships with individuals involved in the submission of this paper.

Disclaimer

The funding sources had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, or the Presbyterian Health Foundation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ungvari, Z., Fekete, M., Fekete, J.T. et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and its protective effects against colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 26 studies with 2,217,404 participants. GeroScience (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01296-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01296-9