Abstract

Research has begun to document the impact of COVID-19, and corresponding restrictions associated with the pandemic, to several unintended consequences including increased rates of family violence. Given these findings, there have been calls for research to understand predictors of family violence, and how such predictors may shift during differing periods of the pandemic. Rooted in the family stress model and social disorganization theory, this study used call for service data from two police departments located in the Midwest of the United States, to examine whether the relationship between sociostructural indices on the number of family violence incidents varied in the times before, during, and after COVID-19 Safer-at-Home orders. Based on a series of negative binomial regression models, results show that the association between neighborhood (i.e., Census block group) concentrated poverty, the percentage of the population between 15 and 24 years of age, and the percentage of the population that identify as male on family violence was amplified during and/or after the adoption of the Safer-at-Home order. Results also indicated that the Safer-at-Home order eradicated the once significant effect of residential mobility and family violence incidents. Lastly, although neighborhoods located within the more populous and metropolitan city experienced fewer family violence incidents, compared to the mixed rural-suburban city, the gap in the number of incidents per neighborhood decreased in the times following the enactment of the Safer-at-Home order. Based on these findings, proactive and reactive policies regarding resource dissemination and increasing neighboring activities are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Family and domestic violence is a public health concern, with estimates showing that that 1 in 3 females and 1 in 5 males worldwide experience some form of family violence during their lifetime (Kolbe & Büttner, 2020; World Health Organization, 2021). Even more troubling are yearly estimates of domestic violence. Specifically, estimates suggest that as many as 1 in 4 women and 1 in 9 men are victims of domestic violence — a figure that translates to 10 million people experiencing family violence every year (Huecker et al., 2022; Lewis et al., 2019; Sapkota et al., 2019). Perhaps one of the most troubling statistics surrounds the annual number of deaths that are the result of domestic violence. Here, researchers have estimated that each year, domestic violence is the cause of more than 1,500 deaths (Harland et al., 2021; Huecker et al., 2022; Wahi et al., 2019). Based on these estimates, it is clear that family violence is a serious epidemic occurring in the United States. Most notably, these estimates were generated prior to the inception of the COVID-19 global pandemic, which led to unprecedented social distancing efforts across the world.

Indeed, since March of 2020, research has investigated the impact of the novel coronavirus (i.e., coronavirus disease, COVID-19; World Health Organization (WHO), 2020), with much of the preliminary research exploring the physical health impacts stemming from this virus, while our understanding of social distancing efforts connected to the public’s social wellbeing are less understood. In the limited research examining the impact of social distancing on social outcomes, the growing body of recent research has demonstrated how the restrictive measures stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in unintended consequences on a host of outcomes. For example, the policies designed to stop the spread of the virus (e.g., “Safer at Home” and “Shelter in Place” orders) have been associated with negative mental health outcomes (Carvalho Aguiar Melo and de Sousa Soares, 2020; Konkel, Harris, & Hoffman, 2022; Marroquín et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020); increased substance abuse and drug overdoses (Czeisler et al., 2020; Engel et al., 2020; Mohler et al., 2020; Konkel et al., 2022; Slavova et al., 2020); the introduction of unique barriers to service access and utilization (Weisler & Chrisman, 2020); and increased crime and victimization rates (Brantingham et al., 2021; Campedelli et al., 2020; Daigle et al., 2021; Eisner & Nivette, 2020; Halford et al., 2020; Kim & McCarty, 2022; Mohler et al., 2020; Rosenfeld et al., 2022).

In addition to these consequences, perhaps one of the most consequential, albeit unintentional effects of social distancing efforts, can be linked to the increased risk for family violence. Although these efforts were aimed to reduce the spread of the virus, siloing people within their homes resulted in contexts often favorable to abusers, such as heightened social isolation, surveillance of movement within one’s home, and controlling or monitoring daily activities from household members. Given this, mounting evidence has demonstrated that an additional crisis stemming from COVID-19 is simultaneously occurring – one that some have coined the domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic (Humphreys et al., 2020; Kofman and Garfin, 2020; Pereda and Díaz-Faes, 2020; Piquero et al., 2021). In fact, a recent meta-analysis found an increase in domestic violence during and post-COVID-19 related restrictions across each of the 29 studies included in analysis, of which the prevalence rate of domestic violence was found to increase by an average of 8% (Piquero et al., 2021). Because growing evidence indicates that a significant portion of the population was subjected to domestic violence prior to the pandemic, coupled with an increased prevalence rate of domestic violence associated with Safer-at-Home orders, it is critical to understand what factors impact domestic violence, as these factors can be targets for change in intervention efforts.

Given the importance of identifying factors that impact domestic violence for prevention efforts, researchers have identified a host of risk factors connected to family violence. At the individual-level, correlates such as chronic illness, mental health concerns (e.g., depression, psychopathology and adjustment problems), or engaging in risky behaviors (e.g., alcohol, drug abuse, criminal history, history of violence in the home) correspond to heightened rates of domestic violence (Kraanen et al., 2014; Spencer et al., 2019; Stover, Urdahl, & Easton, 2012; Turner et al., 2013). Contextual factors have also been implicated as risk factors for family violence, and include indicators reflective of sociostructural disadvantage (e.g., low socioeconomic status [e.g., SES], financial hardship, single parent household, and neighborhood violence) (Chan, 2014; Turner et al., 2013). Together, these established risk factors were likely heightened and compounded during the pandemic, especially when considering the economic and social constraints associated with social restriction and commerce shutdown orders (see Brodeur et al., 2021). Stated differently, factors akin to economic constraints and unemployment, coupled with pandemic-related stressors in the home (e.g., homeschooling or childcare, decreased “alone” or personal time), may also lead to an increased engagement of maladaptive coping strategies, all of which escalate the risk of family violence (Piquero et al., 2021).

Although risk factors linked to family violence are well-documented, contextual risk factors related to Safer-at-Home orders on family violence during the pandemic has received less attention. Though work has begun to explore risk factors associated with COVID-19 and related policies on family violence – often providing narrative accounts, reviews, or identifying prevalence rates of domestic violence – there is a continued need for exploration in identifying risk factors associated with family violence that may be unique to the pandemic era and corresponding policies associated to the pandemic. In other words, despite extensive work emerging on domestic violence and its connection to COVID- 19, there are some limitations of this work worth highlighting. First, although early studies published at the start of the pandemic were incredibly important to highlight serious concerns on the impact of stay-at-home orders on domestic violence, some of these studies have methodological limitations that deserve consideration. Some limitations include the use of convenience or cross-sectional samples, limiting inferences on national trends despite findings being presented as representative in the media (see Reingle Gonzalez et al., 2020 for commentary). Second, of the research published on domestic violence and COVID-19, much of this work has centered on identifying changes in prevalence rates pre-, during, and post-COVID-19, and some work has extended beyond this focus to also include identifying individual-level correlates. As described in Letourneau et al. (2022) review of family violence during COVID-19, factors such as increased stress, burnout, mental illness, and isolation were consistent risk factors identified across 29 studies. Because of a large focus on identifying individual-level risk factors, there is limited knowledge on contextual indices that increase the risk of family violence. Given this backdrop, the current study aims to fill part of this void in the empirical literature through identifying neighborhood-level correlates associated with increased family violence calls for service in the times before, during, and post-COVID-19 Safer-at-Home orders. This is an imperative line of inquiry, as this can signal the areas in the greatest need of resources for prevention efforts.

Literature Review

Family Violence and COVID-19

Research has documented the detrimental effects associated with violence in the immediate family context — with some researchers arguing that family violence is among one of the most serious forms of victimization (Kendall-Tackett, 2003). Indeed, neurobiological studies have documented how the lifetime effects of chronic stress associated with an abusive home can lead to neurobiological deregulation (McEwen, 2017). Neurobiological deregulation, in turn, can affect neurological and brain development, and in some cases, modify ones’ stress response to violence, which has the potential to lead to a cycle of violence (Caspi et al., 2002). Emerging evidence has also documented how policies related to the COVID-19 pandemic have led to an increase in family uncertainty and to the exacerbation of existing stressors (Anser et al., 2020), which may prime an environment conducive to immediate and long-term effects associated with family violence.

Further, researchers have highlighted how pandemics, including COVID-19, can lead to a multisystem collapse with huge mounting costs related to individual- and contextual-level consequences (Masten & Stefanidi, 2020). In other words, COVID-19 is not only a dangerous infection impacting physiological health, but is also disrupting the operations of systems needed for well-being like healthcare, work, education, financial operations, transportation, emergency and social services, manufacturing, and the government (Masten & Stefanidi, 2020). Consequently, given the challenges posited by COVID-19, vulnerability for family violence is perhaps at its highest. Notably, research has documented this susceptibility with some studies showing that during the pandemic intimate partner and family violence increased by 8% to 46% (Drotning et al., 2023; Piquero et al., 2021). Similarly, the National Domestic Violence Hotline saw a 9% increase in contacts to the hotline compared to prior years in which social distancing was not enforced. Although research is still focused on identifying pandemic-related risk factors associated with family violence, there is some evidence that factors like loss of income, sexual identity, and living with a partner and others (e.g., parents and/or siblings) in the home significantly doubled the odds of experiencing a variety of forms of family violence (Drotning et al., 2023). Other studies examining factors that increased perpetration of domestic physical violence during the coronavirus pandemic found structural risk factors, such as low SES or living with a partner compared to peers, as well as individual-level risk factors, such as anger and cumulative stressors, significantly increased the likelihood of domestic physical violence perpetration (Steinhoff et al., 2021).

Because Safer-at-Home orders often mirror isolated contexts that are frequently used by perpetrators in abusive situations, calls for more comprehensive analyses of ecological and contextual factors related to domestic violence during the pandemic have been made (Pereda and Díaz-Faes, 2020). Although previous research has revealed that contextual factors associated with high-stress environments are a major predictor of domestic violence (Coulton et al., 2007; Patwardhan et al., 2017), identifying what neighborhood characteristics can be strengthened to support families during high-stress times are especially important to identify.

Theoretical Perspectives Connected to Family Violence

Several theoretical perspectives have been applied to explain domestic violence, including social learning, social information processing, attachment, social control, and social disorganization theories (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990; Lo, Chan, & Ip, 2019; Olsson et al., 2020; Rebellon & Van Gundy, 2005). One theory that may be particularly useful to draw upon in understanding family violence during the pandemic is the family stress model (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Indeed, the family stress model has a specific focus on how stressors connected to disadvantage may impact relationships and behaviors, which may be a perspective especially useful to understand family violence in the context of the extreme uncertainty caused by COVID-19.

Briefly, the family stress model suggests that both perceived and actual economic hardship leads to a deterioration in meeting basic family needs and financial obligations, which can result in cascading hardships. These hardships can include deterioration in relationships, especially martial relationships, and negative financial pressures. When economic pressure is high, relationships are at heightened risk for emotional distress, such as anxiety, anger, depression, and alienation, as well as for behavioral issues including increased substance usage and antisocial behaviors (Conger et al., 2010). Maladjusted responses to economic pressure, in turn, lay a foreground conducive to family violence.

It is noteworthy that there is empirical evidence supporting the family stress model and how it relates to domestic violence. Specifically, using the family stress model, studies have shown that economic hardship exacerbates emotional distress for both partners in a relationship, thereby leading to increased conflict (Conger et al., 2002). Relatedly, negative perceptions of financial well-being, a correlate of economic hardship identified by the family stress model, is also associated with an increased risk of violence in the home (Fox et al., 2002). Similarly, Lucero and colleagues (2016) found that although familial economic instability was connected with family violence, this effect was mediated by parental stress.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has largely increased actual and perceived economic strain, thereby potentially heightening family stress and environments conducive to family violence. Also noteworthy is that these studies, in general, find that patterns of the family stress model were disproportionately concentrated in low-wage service or health jobs, and low-income households. Because of this, a neighborhood-level perspective may be useful in understanding how macro-level variables associated with the pandemic, and policies associated with it, impact the occurrence of family violence. Indeed, measures that examine the macro-level composition of households within neighborhoods before, during, and after the pandemic — like the percentage of males, percentage of people aged 15-24 years, and the percentage of families within block groups — may be useful to understand how the family stress model and corresponding environments impact family violence. Further, given that prior studies have found that the explanatory power of the family stress model was largely concentrated in low-income households, understanding if and how the relationship between macro-level factors like concentrated poverty and disadvantages’ influence on family violence would also be useful.

The Role of Neighborhood Characteristics, COVID-19, and Family Violence

Perhaps one of the most established trends of criminological/sociological research is the acknowledgement that social problems, including rates of delinquency or violence, tend to coalesce in similar geographical concentrations (Testa & Furstenberg, 2002). In theorizing how and why certain neighborhood characteristics account for variations in deviant and violent behavior, social disorganization theory emerged (Shaw & McKay, 1942). Briefly, social disorganization theory argues that geographic enclaves, such as neighborhoods, are a complex system of networks with shared norms and goals, routines, and institutional resources (Sampson et al., 2002; Shaw & McKay, 1942). These networks have structural dimensions, including informal (e.g., density of friendship ties and acquaintanceship) and formal (e.g., organizational participation) social controls, which influence the collective supervision that the community directs toward local problems. Together, social disorganization differs from other criminological theories that focus on individual-level characteristics by instead examining indicators of the sociostructural environment that result in making some areas more prone to crime/victimization, and conversely, allow other areas to ward off offending. Here, social disorganization theory can be used as a place-based perspective to discern how factors connected to locations impact social problems.

Although researchers have applied social disorganization theory to a slew of outcomes, the original framing of the theory highlighted that level of neighborhood “organization” is bred from a combination of conditions — with specific focus on poverty, residential instability, and heterogeneity (Shaw & McKay, 1942). These neighborhood conditions, then, shape social dynamics, which manifest certain patterns of social behaviors. Notably, the social and environmental context of a neighborhood has the ability to encourage resident cohesiveness and engagement, which in turn may allow for higher control and perceptions of intervention, which can offset consequences associated with disadvantage.

Using factors identified by social disorganization theory as a backcloth, it is conceivable that COVID-19 may have impacted neighborhood sociostructural context, as well as disrupted existing neighborhood ties and controls. Because the pandemic disrupted financial systems and sources of formal and informal social control, it is likely the pandemic and policies resulting because of COVID-19 intensified levels of socioeconomic disadvantage in places that may have had a higher baseline risk for deviance. Similarly, neighborhoods with a greater proportion of residents with lower socioeconomic standing may perceive and experience additional burdens and hardships. This may result because of the inability of neighbors to provide assistance or relief as they are already attempting to address their own stressors and strains. Breakdowns in neighboring behaviors may be even greater in neighborhoods with higher levels of mobility, as it may be more difficult to create and maintain lasting ties in neighborhoods where there are higher rates of residential turnover. Here, beyond limited access to social ties and neighboring behaviors, it is possible that higher levels of mobility also correspond with higher degrees of anonymity, which can result in additional breakdowns of informal or formal social controls. This is especially salient to instances of family violence, as the family stress model indicates that perceived and real economic stress can precipitate family violence, and moreover, it is likely that this is especially true for neighborhoods that may have high residential mobility and disorganization. Further, family violence victims may not feel that they have the supports or control in place to assist in situations precipitating to, or following acts of family violence. For this reason, neighborhood standing and dynamics — like factors that assess concentrated poverty, location, disadvantage, and mobility — are likely to be important factors to consider when examining the interplay between context and family violence.

Current Study

Collectively, the relationship between COVID-19 and heightened family stress has already been established. Separately, a wealth of knowledge is being generated on the impact of COVID-19 on family violence, of which, many studies rely on narrative accounts or systematic reviews to hypothesize risk factors connected to family violence. Such methodologies may leave room for exploration through empirical research. One current unknown is if and what contextual indices are tied to locations of family violence incidents before, during, and after safer-at-home orders. As such, this study considers what neighborhood characteristics, such as disadvantage or residential mobility, are associated with the locations of family violent incidents.

Methodology

Sample

The sample for this study includes all 76 Census defined block groups that are located within two Midwestern cities. Of all block groups, 32 were located in “City A,” which is comprised of both rural and suburban land areas, whereas 44 block groups were located in “City B,” which is a suburban area located within the most populous county within the sample state.

According to the United States’ Census Bureau (2024), in 2020, City A and City B were each home to approximately 50,000 residents (49,939 residents and 48,380 residents, respectively); however, the percentage of the population comprised of males is slightly higher in City A (51.2%) than in City B (47.4%). The majority of the population in both City A and City B identify as non-Hispanic White (75.1% and 80.9%, respectively); however, the percentage of the population who identify as other races varies across the two cities (see Appendix: Table 4). The vast majority of residents in both cities have earned their high school diploma or a higher degree (City A = 91.5%; City B = 97.8%); however, the percentage of residents who earned at least a bachelor’s degree is 2.6 times higher in City B (61.0%) than in City A (22.9%). Although both cities have similar percentages of the population who reported being employed (City A = 68.2%; City B = 67.1%), the median household income in City B is approximately 1.6 times higher than that in City A. Along the same vein, the percentage of the population in City A with annual household incomes that fall below the poverty line is nearly twice as high as the percentage of the population in City B (11.4% and 5.8%, respectively).

In terms of housing, roughly 60% of residents in both cities reside in homes that they own (City A = 60.8%; City B = 61.9%). The median value of owner-occupied housing units in City B is approximately 1.9 times more expensive than in City A, in which the median value of owner-occupied units in City B is $291,600, compared to $154,300 in City A. Similarly, the median monthly rent among those living in renter-occupied units is about 1.5 times higher in City B ($1,312) than in City A ($853). Appendix B shows how socioeconomic and demographic data in Cities A and B vary across block groups within each respective city.

When comparing the number of UCR Part I offenses that took place in each jurisdiction, during the 2020 calendar year, there were 146 Part I offenses in City A and 69 Part I offenses in City B (Wisconsin Department of Justice, n.d.). Specifically, City A had 109 aggravated assaults, 21 rapes, 15 robberies, and 1 murder, whereas City B had 35 aggravated assaults, 2 rapes/sex offenses, 32 robberies, and 0 murders. Turning to Part II Offenses, City A observed 842 Part II offenses and City B observed 1,188 Part II offenses. Specifically, City A had 97 burglaries, 709 cases of larceny-theft, and 36 motor vehicle thefts, whereas City B had 77 burglaries, 1,004 cases of larceny-theft, and 107 motor vehicle thefts. Here, we observe that although City A had a larger volume of violent crimes, City B had more property crimes.

Data and Measures

Dependent Variables

Data on all family violence calls for service in either of City A or City B that took place between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2021 were obtained from the two respective police department. Based on these data, four dependent variables were created. The first measure captures the number of family violence incidents per block group that were reported to the police at any point during the data collection period (i.e., January 1, 2018-April 21, 2021) (All Family Violence; N=2,314). The second measure reflects the number of reported instances of family violence per block group that took place prior to the inception of the state’s Safer at Home orders (i.e., January 1, 2018-March 24, 2020) (Pre-COVID Family Violence; N=1,921). The third dependent variable measures the number of family violence calls for service that were made during the state’s Safer at Home mandate (March 25-August 13, 2020) (COVID Family Violence; N=131). The fourth and final measure indicates the number of family violence incidents per block group that took place during the time the followed the lifting of the Safer at Home order (August 14, 2020-April 21, 2021) (Post-COVID Family Violence; N=262).

Independent Variables

Data on independent variables, aside from the binary measure (City) used to capture City A versus City B, were all collected from the 2019 United States Census Bureau’s American Communities Survey (5-year estimates). First, because cohabitating with others has been found to be predictive of family violence, data were obtained on the number of housing units within each block group that identified as being comprised of a family (% Families). This count was then transformed into a percentage to allow for comparisons between block groups and interpretability in findings. Second, because adolescents and young adults may be more likely to be the aggressor and/or victim in family violence incidents, the number of residents aging between 15 and 24 years of age within each block group was collected (% Age 15-24). Again, for the reasons discussed above, this count was transformed into the percentage of residents who were between 15 and 24 years of age. Third, due to the literature identifying males as being more likely to be perpetrators of violence resulting in greater bodily injuries (Ehrensaft, Moffit, & Caspi, 2004; for a meta-analysis see: Archer, 2000; Capaldi et al., 2012), the number of males per block group was collected, and then used to calculate the percentage of block group residents who identified as male (% Males).

Fourth, because the pandemic affected the economic standing of many families and individuals, as well as the stress associated with financial strains (Oyesanya et al., 2015), it is hypothesized that neighborhoods that were experiencing high levels of concentrated poverty may disproportionately feel the impacts on economic downfalls during the pandemic. Therefore, instances of family violence may be more prevalent in these areas. For this reason, a measure reflecting concentrated poverty was created using Massey’s (2001) Index of Concentrated Extremes, in which:

Here, a block group scoring -1 indicates all households have annual earning of at least $100,000, whereas a score of +1 indicates extreme concentrated poverty, meaning all households within that block group have annual earnings below the poverty line (i.e., annual earnings less than $25,000).

The final two independent variables are factor scores based on five variables that were entered into a principal components factor analysis, which employed a varimax rotation. These variables included the percentage of residents per block group who reported: having a level of educational attainment that was less than a receiving their high school degree/GED, being unemployed, receiving public assistance or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (“SNAP”), living within a rented housing unit, and moving into their current housing unit within the past five years. Based on the factor analysis, two discrete regression-based factors emerged (Eigenvalue = 1.382). The variables that loaded onto the first factor, which are reflective of socioeconomic disadvantage (and each variable’s loading) included: percent of block group residents receiving public assistance or SNAP (.912), percent of residents who reported being unemployed (.761), and percentage of residents who reported educational attainment that was less than a high school degree (.684). The remaining two variables loaded onto the second factor, which is consistent with measures capturing residential mobility. These variables (and each variable’s factor loading) included: the percent of residents who reported moving into their current housing unit within the past five years (.941) and the percent of residents who reported living in a rented housing unit (.890).

Analysis

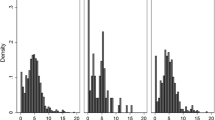

Based on the measures described above, descriptive statistics and chi-squares for each of the dependent variables were examined. Because the mean for each dependent variable was smaller than the associated standard deviation, it was likely that overdispersion was present among each of the dependent variables. To account for the non-normality in the distribution of residuals and variance, as well as the non-linear relationship between the independent and dependent variables within these models, negative binomial regression models were employed using Stata 18’s command nbreg.Footnote 1

The first of these models tested the association between each independent variable and the number of family violence calls for service per block group that took place during any point within the study period. The second model tested the relationship between all independent variables and the number of family violence calls for service per block group that took place in the time proceeding the COVID-19 Safer at Home orders. The third model examined the impact of each independent variable on the number of family violence calls for service per block group that took place during the Safer at Home order. The final model tested the association between each independent variable on the number of family violence calls for service per block group that took place following the disbandment of the Safer at Home order.

To understand if and how the contextual predictors effect on family violence calls for service varies over time, we compare the equality of coefficients across our three time periods (pre-COVID, COVID, post-COVID). Specifically, to determine whether the effects of the contextual predictors varied across the time period, we compared the models’ using seemingly unrelated estimation – Stata’s suest command– and linear combination tests– lincom command.Footnote 2 As a robustness check (not presented), we compared the z-values derived from lincom with Paternoster and colleagues (1998) adjusted z-formula to test for the equality of regression coefficients. The results using Paternoster et al. (1998) adjusted z-formula were substantively similar to the findings presented here.

Results

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. During the entire study period, 2,314 incidents of family violence took place across all 76 block groups. The average number of family violence incidents was 30 incidents per block group, with an average of 25 incidents occurring pre-COVID, 1.7 incidents taking place during COVID, and 3.4 incidents occurring post-COVID.

Table 2 presents findings on the relationship between neighborhood-level predictors and incidents of family violence. As shown in Model 1, several predictors were associated with family violence incidents during the entire study period including concentrated poverty, city location, and mobility. In other words, neighborhoods located in City A experienced a higher number of family violence incidents compared to those located in City B. Additionally, block groups that had higher levels of residential mobility and concentrated poverty also were associated with a greater prevalence of family violence incidents. More specifically, compared to City A, which is comprised of more rural and suburban land areas, City B was associated with an 83% decrease of family violence incidents that were reported to the police. Further, residential mobility was associated with an increase in the number of reported family violence incidents. Here, each standard deviation increase above the mean score of residential mobility was associated with a 43% increase in the number of calls for service for family violence incidents. Finally, although only reaching a level of marginal significance, block groups with a higher concentration of poverty increased the likelihood of experiencing an incident of family violence by nearly 5-fold. Notably, these findings are largely consistent with Model 2, which examines family violence-related calls for service that took place during the period before Safer-at-Home orders (i.e., pre-COVID).

Next, the effect of all predictors on family violence incident calls that took place during the COVID-19 Safer-at-Home orders were examined (see model 3 of Table 2). Notably, some findings differed during the COVID timeframe, compared to the pre-COVID period, with the effect of living in less populated areas (i.e., City A) remaining consistent to pre-COVID models. Interestingly, the composition of households (i.e., individuals versus family households) and concentrated poverty became significantly associated with an increase in the number of incidents of family violence. More specifically, for each one unit increase in the percentage of block groups residents between 15 to 24 years of age, there was an 11% increase in the number of family violence incidents. Further, unlike the pre-COVID time period, concentrated poverty was not only a highly significant predictor of family violence incidents, but the magnitude of concentrated poverty on family violence-related calls for service also increased. Here, for each one unit increase in the level of concentrated poverty within a given block group was associated with that block group experiencing 18 times more family violent incidents. Notably, the effect of residential mobility was reduced to insignificance during the Safer-at-Home time period.

Finally, Model 4 examines the period of time following the disbandment of the Safer-at-Home order (i.e., post-COVID). Block groups with a larger percentage of residents between 15 and 24 years of age and concentrated poverty were no longer significantly associated with incidents of family violence. Although these variables were no longer significantly associated with the number of family violence incidents, within this model, the percentage of block group residents who identified as males became a significant predictor. Specifically, for each one percent increase in the percent of males within a given block group, a 7% increase in the number of family violence-based calls for service was observed. Interestingly, the association between residential mobility and family violence incidents re-emerged, and although this effect only reached a level of marginal significance, the association between residential mobility and family violence incidents was strongest during the post-COVID timeframe. Here, within the post-COVID model, the impact of residential mobility on family violence incidents was stronger than during the pre-COVID time frame, in which each standard deviation increase above the mean score of residential mobility was associated with a 46% increase in the number family violence incidents during the time following the Safer-at-Home order (pre-COVID IRR=1.39). Lastly, block groups within City B were associated with having fewer family violence-related calls for service.

Coefficient comparison tests are presented in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, coefficients significantly differed across time periods on four contextual predictors, including: percentage of males per block group, city location, disadvantage, and mobility. The coefficients for the predictors of the percentage of people aged 15-24, the percentage of families, and concentrated poverty; however, do not appear to be significantly different from one another. In general, these findings suggest that demographic factors, like the percentage of males in a given block group, location — such as being in a less populated, rural-suburban mixed land area (e.g., City A) — and areas with higher levels of disadvantage and mobility were all associated with a significant increase in family violence-based calls for service during the pandemic, and these associations remained elevated after the pandemic. More specifically, the impact of block groups with a larger percentage of residents who identify as male on family violence-based calls for service significantly increased during COVID (Ζ=2.57, p<.01) and remained elevated in the post-COVID time period (Ζ=2.28, p<.05) compared to the pre-COVID time period. Relative to City A, City B experienced a significant reduction on family violence calls for service during COVID (Ζ=-5.05, p<.001), and this reduced association remained consistent during the post-COVID time period (Ζ=-5.08, p<.001). The relationship between disadvantage and family violence calls for service significantly increased during COVID (Ζ=2.61, p<.01), and post-COVID (Ζ=2.15, p<.05), compared to pre-COVID; however, the impact of disadvantage on family violence calls from COVID to post-COVID (Ζ=-2.60, p<.01) significantly decreased. Finally, compared to pre-COVID, the association between mobility and family violence calls significantly increased during the COVID (Ζ=2.28, p<.05) and post-COVID (Ζ=2.19, p<.05).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic not only had a global health impact, but also altered daily activities, economic standing, and social phenomena in virtually every community across the world. In this study, we consider how societal changes stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Safer-at-Home orders, social distancing, commerce shutdowns) impacted family violence incidents within two Midwestern cities. Specifically, analyses tested whether the association between sociostructural indices and the number of family violence related calls for service varied across the times prior to, during, and following COVID-19 Safer-at-Home orders. In doing so, analyses revealed that, indeed, these factors varied in significance and magnitude across the timeframes examined. Below, and rooted in the family stress model and social disorganization theory, we offer explanations as to why these variations may exist.

First, we note that the association between concentrated poverty and family violence incidents was found to vary across COVID-related timeframes. Although the effect of concentrated poverty across time periods was less pronounced in the equality of coefficients tests, we find the direct effect of concentrated poverty on predicting family violence across models to be interesting. Specifically, the positive and marginally significant relationship between concentrated poverty and family violence that was observed prior to the Safer-at-Home order, not only became a highly significant predictor of family violence, but also increased in magnitude by nearly 370% (IRR=5.02 and IRR=18.42, respectively). Here, analyses indicated that there was approximately 18 times more incidents of family violence that took place in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty, than in neighborhoods at the average level concentrated poverty during the Safer-at-Home order. Prior to the order, however, neighborhoods with higher concentrations of poverty only corresponded to a rate of five times more incidents of family violence relative to neighborhoods with average level of concentrated poverty.

Although the literature has identified financial stress as an important predictor of intimate partner violence (Neff, Holamon, & Schluter, 1995), we find the variation in the effect size of concentrated poverty across timeframes to be of key interest. When attempting to understand this amplification in effect size, we rely largely on the family stress model, and argue that the financial and economic burdens resulting from the shutdowns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may have disproportionately impacted individuals who were already experiencing economic struggles. Specifically, those who may have been living “paycheck to paycheck” prior to the economic hardships brought forth by the pandemic, may have experienced the greatest financial strains, as they may have not had any sort of financial cushion to rely on. Furthermore, because many other people in their neighborhoods may have also experienced similar hardships, it is possible that within these communities, people were unable to lend/borrow money or other resources from neighbors. This financial strain, coupled with cohabitants and family members being pushed into tight living quarters and in constant physical proximity, may have amplified stress, and subsequently, resulted in disputes and violent outcomes. Once the Safer-at-Home order was lifted, the impact of concentrated poverty decreased to a non-significant level, with the effect diminishing lower than in the time prior to the inception of the order. This indicates that once there was an economic upturn, it is possible that many of the stresses associated with financial hardship and extreme poverty greatly dissipated.

Next, social disorganization theory surmounts that lower levels of socioeconomic disadvantage and higher levels of residential mobility lead to a breakdown in ties and the ability to exert controls, which the literature points to this breakdown in ties, cohesion, and control as predictors of intimate partner violence (Browning, 2002; Garrett & Libbey, 1997; Rothman et al., 2011). Here, when more people are transitioning in and out of living within a given neighborhood, not only is there greater levels of residential anonymity, but also, lower levels of vested interest in neighborhood goal achievement, as people are likely to anticipate moving from their current neighborhood as soon as it is feasible. This can lead to lower desire to participate in neighboring behaviors, including partaking in informal social control and/or engaging with formal controls. In turn, this may lead to higher levels of offending, as the risks for intervention and apprehension are perceived to be lower than in more engaged and cohesive neighborhoods.

Perhaps it is for these reasons that the equality of coefficients results indicated that disadvantage had a significant moderating effect on family violence (rather than a direct effect) when interacting with the three different timeframes. Specifically, the impact of disadvantage on family violence was significantly higher during COVID, and remained elevated during post-COVID compared to pre-pandemic timeframe. Although this effect significantly decreased when comparing COVID to the post-pandemic timeframe. In other words, disadvantage, though insignificant in models when accounting for other contextual indices predicting family violence, did significantly differ across the timeframes of interest, with the impact of disadvantage on family violence dissipating once Safer-at-Home orders were lifted. As such, we contend that these findings may show an interplay between disadvantage, family violence, and stressors (e.g., those resulting from the COVID pandemic); however, the direct effect of disadvantage may be, at least in part, masked by the other contextual variables accounted for within the presented models.

Further, analyses for this study found that although there was a positive association between residential mobility and family violence in the time proceeding the Safer-at-Home order, this relationship slightly diminished during the time that the order was in place. The equality of coefficients results were similar, in that the impact of residential mobility on family violence was higher during COVID and post-COVID, compared to pre-COVID. In other words, residential mobility had both a direct and moderating effect on family violence that was contingent on the time period. We posit that this effect may have occurred because most residents were sequestered in or near their homes their homes during the order. This has the potential to lead to a decrease in anonymity, as people were often times more likely to see their neighbors in their homes or outside in their yards. Further, in terms of family violence, the actual or perceived likelihood of neighbors directly intervening or reaching out to formal controls may have been higher, as potential abusers may have become aware that their neighbors were likely to be home and within “earshot” of any disturbances that may have taken place or witness the aftermath of a violent incident. Although the association between residential mobility and family violence somewhat re-emerged following the disbandment of the order, this effect was only found to reach a level of marginal significance, which indicates that, perhaps, the impact of decreased anonymity and increased guardianship somewhat remained following the lifting of the order. Collectively, we purport that these trends can be explained by the Safer-at-Home order unintentionally activating guardianship and perceived controls within neighborhoods where residents typically had kept to themselves prior to the order.

Third, findings from analyses established that during the Safer-at-Home order, the percentage of the population between 15 and 24 years of age had a direct, and significant effect on increasing the relative risk of family violence incidents, though this effect was only evident during the time when the order was in place. The percentage of people between 15 and 24 years of age did not significantly differ across time periods according to the equality of coefficients test. This aligns with previous literature showing that age is negatively associated with adulthood intimate partner violence, meaning that once one reaches 18 years of age, their likelihood to engage in or be the victim of intimate partner violence decreases (Benson et al., 2004; Kim, Laurent, Capaldi, & Feingold, 2008; Rodriguez, Lasch, Chandra, & Lee, 2001, for a meta-analysis see Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012). This relates to the current study’s findings, in that individuals who are aging from late adolescents to early adulthood were more likely to be at home during the Safer-at-Home order. We explain the positive relationship between this age group and increased family violence incidents as simply the amount of time spent together between people in that age group increased as a result of the Safer-at-Home order. Due to increased exposure among those in this group with others, this may have increased the opportunity to act violently towards or be violently victimized by a family member. Once the Safer-at-Home order was lifted, this effect was no longer significant. Stated differently, once schools and businesses re-opened, it was likely that the amount of at home, face-to-face time spent between individuals in this age group or others decreased, thus decreasing the opportunity for offending and/or victimization.

Additionally, the association between the percentage of males who lived within a neighborhood and family violence incidents was impacted by the Safer-at-Home order. Indeed, the equality of coefficients results showed that the effect of the percentage of males on family violence was significantly greater during COVID and post-COVID compared to pre-COVD. In the direct effect models, this relationship was only found to be significant during the time following the disbandment of the Safer-at-Home order, and was found to be positive. Here, and pulling from the family stress model, it is possible that the financial strains resulting from the pandemic and economic downfall were felt more intensely by males, and that when statuses did not quickly improve following the re-opening of many businesses, additional stressors were likely felt. The compounding of stressors and financial burdens brought forth by the pandemic, coupled with the traditional view of males as “breadwinners,” may partially explain why neighborhoods with a greater percentage of the population identifying as males experienced heightened numbers of family violence incidents. Although females have been found to be as likely or more likely to be aggressor in family violence incidents, male aggressors are more likely to inflict more serious injuries (Ehrensaft, Moffit, & Caspi, 2004; for a meta-analysis see: Archer, 2000; Capaldi et al., 2012), and therefore, these incidents may have been more likely to be reported to law enforcement. It is also worth noting that our findings align with Steinhoff et al. (2021) longitudinal study conducted in Switzerland on domestic physical violence perpetration in which they found perpetration of domestic violence increased in males following lockdown initiatives.

Lastly, across all timeframes, the more populous and metropolitan city (i.e., City B) experienced fewer family violence incidents compared to the less populous city that was a mixture of suburban and rural land areas (i.e., City A). This finding was replicated in the equality of coefficients results. Of interest, the pandemic dampened the magnitude of this association, meaning that beginning with the Safer-at-Home order, the playing field was somewhat evened among the two cities, in which the difference in the number of family violence incidents occurring in block groups between the two cities was reduced once the order came into effect, and the difference closed even more in the time following the lifting of the order. Here, we posit that the Safer-at-Home order increased strain for those in City B at a higher level during the order, and then, these stressors continued to grow even after the order had been lifted. This may, in part, explain the steeper increase in family violence calls for service among block groups in City B compared to those in City A.

Theoretical and Policy Implications

Notably, these findings can be used to inform theoretical and policy implications. As mentioned above, our findings largely support the intertwining of the family stress and social disorganization theoretical frameworks. As explained above, the family stress model argues that both perceived and actual economic hardship can lead to deterioration in family relationships and create situations that may be conducive to domestic violence. Our findings are consistent with the family stress model in that our predictors that proxy economic and social stress significantly exacerbated conditions that can lead to family violence. For example, contextual indices that proxy economic stress, like concentrated poverty, had a large and significant direct effect on family violence calls during the pandemic, holding constant factors drawn from social disorganization theory.

Other indicators of economic hardship (e.g., disadvantage), elicited positive moderating effects on family violence and these effects remained significant in the post-pandemic era when compared to the pre-COVID timeframe. These findings highlight that events that heighten stress, such as the global economic crisis resulting from the COVID pandemic, are capable of intensifying the already present effects of economic hardship on family violence incidents. Stated differently, the findings from this study suggest that when economic pressure is high, maladjusted responses to the economic pressure (or concentrated poverty), such as engaging in family violence, resulted at a higher frequency. Perhaps the mantra “the straw that broke the camel’s back” applies here, in that residents in neighborhoods who had been previously successful at coping with economic hardships/poverty, were unable to do so as effectively with the added financial burdens and stressors/frustrations brought forth by the shutdowns resulting from the COVID pandemic. Although prior research has suggested economic hardship exacerbated emotional distress for both partners (Conger et al., 2002), our findings suggest this distress may have been felt more intensely among males. In other words, our findings support both a direct effect of percentage of males within a given block group significantly impacting family violence, holding constant other contextual indices, and a moderated effect between percentage of males and COVID, all of which significantly elevated the risk of domestic violence. Perhaps for this reason, we saw that subgroups that are at increased risk to be a victim of family violence, such as the percentage of people aged 15-24 in a block group, significantly increased the likelihood of domestic violence during COVID.

Based on findings from analyses, we identify potential areas for policy development below. The findings from this study suggest that disturbances to everyday life have an impact on the ecology of a neighborhood, and subsequently, the behaviors of individuals within those neighborhoods. Here, we suggest that both proactive and reactive resources be disseminated among residents who live in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty, high percentages of adolescents and young adults, and higher percentages of male residents. Specifically, circulating information on precursive behaviors tied to family violence, such as social isolation, surveillance of family members by another family member, and controlling tendencies, may help potential victims or neighbors identify potentially problematic behaviors. Further, information on local resources should be provided, and included both law enforcement and social service organizations (i.e., domestic violence hotlines, resource centers, support groups).

Beyond traditional means used to report and receive support for family violence, we also suggest that information on financial resources (e.g., tax credits, employment services, SNAP/public assistance) be shared with individuals living within high poverty neighborhoods. Moreover, sharing strategies to cope with general or financial stress may be advantageous, as individuals may be able to rely on alternative means to cope with stress and frustration. Increasing available information on local services, recreational outlets, and resources targeted at adolescents and young adults may also aid in interrupting cycles of frustration or violence. Lastly, increasing awareness of outdoor or respite activities that allow for breaks from other family members may correspond to a space to decompress, and step away from stresses within the household.

Our final recommendation focuses on the fluctuation in the relationship between residential mobility and family violence that was observed across study periods. Recall, during the Safer-at-Home order, the association between residential mobility and family violence diminished in size to a level of non-significance. In essence, it appears that the Safer-at-Home order worked as a protective factor in this regard, and therefore, it may be beneficial for neighborhoods to maintain and increase ties and perceived surveillance. Activities that may increase neighboring may include integration of community hosted events, such as block parties, “Neighborhood Night Out,” and other low-cost events thereby potentially leading to a decrease in anonymity between neighbors. Hosting such events in conjunction with law enforcement agencies (e.g., Neighborhood Night Out) or other social service institutions may not only bring residents together, but may also lead to increased awareness in local resources, activities, and organizations.

Limitations

As with any study, the current study is not without limitation. First, data on family violence incidents only capture those known to law enforcement. Because it is likely that there were incidents that occurred that were not reported to the police, the data for analysis do not account for all family violence incidents that took place during this study’s timeframe. Future research may be able to combat the dark figure of family violence crime by collecting and analyzing self-report data. Second, additional individual-level factors that are associated with family violence were not included in this study, as we aimed to identify contextual impacts associated with family violence. That said, future research should aim to collect individual-level attributes, both on aggressors and victims, to identify individual characteristics that might be important when considering the dispersion of resources and proactive tactics pointed at decreasing family violence.

Third, other neighborhood-level indices that were not included within this study’s models may be associated with areas with especially high or low frequencies of family violence incidents. Future research should continue to investigate additional correlates to identify areas that may be most at risk for family violence incidents. Fourth, data used for this study may not capture a diverse population. Specifically, City A’s population is predominately comprised by residents who identify as non-Hispanic White (70%), followed by individuals who identify as Asian (12%), Hispanic (12%), and Black (3%) (Census Bureau American Community Survey, 2021). Similarly, City B’s population is largely made up of residents who identify as non-Hispanic White (81%), followed by individuals who identify as Black (7%), Asian (5%), and Hispanic (3%) (Census Bureau American Community Survey, 2021). Because of the vast homogeneity in the racial and ethnic makeup of these cities, the findings may not reflect important contextual effects when considering other races and/or ethnicities, and therefore, may not be generalizable to other populations or geographic areas.

Conclusion

Using family violence calls for service data from two Midwestern cities during the time proceeding, during, and after the Safer-at-Home order, this study found varying effects in the impact of neighborhood context on family violence incidents. Specifically, analysis revealed that the association between family violence incidents and neighborhoods with higher levels of concentrated poverty, as well as greater percentages of residents who identified as male and adolescents/young adults were exacerbated in the time during or after the Safer-at-Home order. On the other hand, the pandemic was associated with a decrease in the relationship between residential mobility and family violence incidents. Further, the protectiveness of living in a more populous and metropolitan city, rather than a mixed rural-suburban city, diminished after the enactment of the Safer-at-Home order. Although a pandemic of this magnitude, and the social ramifications stemming from COVID-19 may not be observed again, it is important to consider these findings in light of how changes in social phenomena and policy may impact stress levels and associated behaviors among residents. By targeting resources and activities favorable to bolstering neighboring behaviors towards neighborhoods who may be at the most heightened risk for family violence following high stress situations, it might be possible to partially mitigate contexts that are conducive to family violence incidents.

Notes

It was determined that Poisson or Negative Binomial Regression models were more appropriate to analyze these data (Coxe, West, and Aiken, 2009). Chi-Square models indicated that overdispersion was present, and therefore, because the assumption of equidispersion was not met, it was deemed that Poisson modeling was not appropriate for the data (Allison, 2009; Coxe et al., 2009). In addition, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values were lower within the Negative Binomial model, compared to the Poisson model, indicating that the Negative Binomial model had a higher level of parsimony.

Lincom is appropriate for nonlinear expressions of coefficients and computes point estimates, standard errors, z statistics, p-values, and confidence intervals for linear combinations of coefficients.

References

Allison, P. D. (2009). Missing data (pp. 72–89). The SAGE handbook of quantitative methods in psychology.

Anser, M. K., Yousaf, Z., Khan, M. A., Nassani, A. A., Alotaibi, S. M., Abro, M. M. Q., ..., & Zaman, K. (2020). Does communicable diseases (including COVID-19) may increase global poverty risk? A cloud on the horizon. Environmental Research, 187, 109668.

Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651–690.

Benson, M. L., Wooldredge, J., Thistlethwaite, A. B., & Fox, G. L. (2004). The correlation between race and domestic violence is confounded with community context. Social Problems, 51(3), 326–342.

Brantingham, P. J., Tita, G. E., & Mohler, G. (2021). Gang-related crime in Los Angeles remained stable following COVID-19 social distancing orders. Criminology & Public Policy, 20(3), 423–436.

Brodeur, A., Gray, D., Islam, A., & Bhuiyan, S. (2021). A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. Journal of Economic Surveys, 35(4), 1007–1044.

Browning, C. R. (2002). The span of collective efficacy: Extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 833–850.

Campedelli, G. M., Favarin, S., Aziani, A., & Piquero, A. R. (2020). Disentangling community-level changes in crime trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chicago. Crime Science, 9, 1–18.

Capaldi, D. M., Knoble, N. B., Shortt, J. W., & Kim, H. K. (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231–280.

CarvalhoAguiarMelo, M., & de Sousa Soares, D. (2020). Impact of social distancing on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: An urgent discussion. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(6), 625–626.

Caspi, A., McClay, J., Moffitt, T. E., Mill, J., Martin, J., Craig, I. W., ..., & Poulton, R. (2002). Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science, 297(5582), 851-854.

Chan, K. L. (2014). Child victims and poly-victims in China: Are they more at-risk of family violence? Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1832–1839.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 685–704.

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38(2), 179–193.

Coulton, C. J., Crampton, D. S., Irwin, M., Spilsbury, J. C., & Korbin, J. E. (2007). How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(11–112), 1117–1142.

Coxe, S., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2009). The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 121–136.

Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057.

Daigle, L. E., Hancock, K. P., & Chafin, T. C. (2021). COVID-19 and its link to victimization among college students. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 46(5), 683–703.

Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250(4988), 1678–1683.

Drotning, K. J., Doan, L., Sayer, L. C., Fish, J. N., & Rinderknecht, R. G. (2023). Not all homes are safe: Family violence following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence, 38(2), 189–201.

Ehrensaft, M. K., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2004). Clinically abusive relationships in an unselected birth cohort: Men's and women's participation and developmental antecedents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(2), 258.

Eisner, M., & Nivette, A. (2020). Violence and the pandemic. Urgent questions for research. HFG research and policy in brief.

Engel, L., Farley, E., & Tilley, J. (2020). COVID-19 and Opioid Use Disorder. Council on Criminal Justice: Washington, DC, USA.

Fox, G. L., Benson, M. L., DeMaris, A. A., & Van Wyk, J. (2002). Economic distress and intimate violence: Testing family stress and resources theories. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(3), 793–807.

Garrett, A. & Libbey, H. (1997). Theory and research on the outcomes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Presented at the child abuse intervention planning meeting, October 3, 1997. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Halford, E., Dixon, A., Farrell, G., Malleson, N., & Tilley, N. (2020). Crime and coronavirus: Social distancing, lockdown, and the mobility elasticity of crime. Crime science, 9(1), 1–12.

Harland, K. K., Peek-Asa, C., & Saftlas, A. F. (2021). Intimate partner violence and controlling behaviors experienced by emergency department patients: Differences by sexual orientation and gender identification. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11-12), NP6125-NP6143.

Huecker, M.R., King, K.C., & Jordan, G.A. (2022). Domestic Violence. StatPearl Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499891/. Accessed June 2023.

Humphreys, K. L., Myint, M. T., & Zeanah, C. H. (2020). Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics, 146(1), e20200982.

Kendall-Tackett, K. A. (2003). Treating the lifetime health effects of childhood victimization. Civic Research Institute.

Kim, D. Y., & McCarty, W. P. (2022). Exploring violent crimes in Chicago during the COVID-19 pandemic: do location, crime type, and social distancing type matter? Journal of Crime and Justice, 45(4), 522–537.

Kim, H. K., Laurent, H. K., Capaldi, D. M., & Feingold, A. (2008). Men’s aggression toward women: A 10-year panel study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(5), 1169–1187.

Kofman, Y. B., & Garfin, D. R. (2020). Home is not always a haven: The domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S199.

Kolbe, V., & Büttner, A. (2020). Domestic violence against men—prevalence and risk factors. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 117(31–32), 534–541.

Konkel, R. H., Harris, M. N., & Hoffman, C. Y. (2022). Are we truly “Safer-At-Home”? A test of contextual effects on mental health and drug overdose incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Drug Issues, 52(3), 349–365.

Kraanen, F. L., Vedel, E., Scholing, A., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2014). Prediction of intimate partner violence by type of substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(4), 532–539.

Letourneau, N., Luis, M. A., Kurbatfinski, S., Ferrara, H. J., Pohl, C., Marabotti, F., & Hayden, K. A. (2022). COVID-19 and family violence: A rapid review of literature published up to 1 year after the pandemic declaration. EClinicalMedicine, 53, 101634.

Lewis, N. V., Dowrick, A., Sohal, A., Feder, G., & Griffiths, C. (2019). Implementation of the Identification and Referral to Improve Safety programme for patients with experience of domestic violence and abuse: A theory-based mixed-method process evaluation. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(4), e298–e312.

Lo, C. K., Chan, K. L., & Ip, P. (2019). Insecure adult attachment and child maltreatment: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(5), 706–719.

Lucero, J. L., Barrett, C., & Jensen, H. (2015). An examination of family and school factors related to early delinquency. Children & Schools, 37(3), 165–173.

Marroquín, B., Vine, V., & Morgan, R. (2020). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113419.

Massey, D. (2001). Does It Take a Village? Community Effects on Children, Adolescents, and Families. In A. Booth & A. C. Crouter (Eds.), The prodigal paradigm returns: Ecology comes back to sociology. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Masten, A. S., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2020). Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1(2), 95–106.

Mazza, M. G., De Lorenzo, R., Conte, C., Poletti, S., Vai, B., Bollettini, I., Melloni, E. M. T., Furlan, R., Ciceri, F., Rovere-Querini, P., the COVID-19 BioB Outpatient Clinic Study Group, & Benedetti, F. (2020). Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.037

McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic Stress, 1, 1–11.

Mohler, G., Bertozzi, A. L., Carter, J., Short, M. B., Sledge, D., Tita, G. E., ..., & Brantingham, P. J. (2020). Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 68, 101692.

Neff, J. A., Holamon, B., & Schluter, T. D. (1995). Spousal violence among Anglos, Blacks, and Mexican Americans: The role of demographic variables, psychosocial predictors, and alcohol consumption. Journal of Family Violence, 10(1), 1–21.

Olsson, A., Knapska, E., & Lindström, B. (2020). The neural and computational systems of social learning. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 21(4), 197–212.

Oyesanya, M., Lopez-Morinigo, J., & Dutta, R. (2015). Systematic review of suicide in economic recession. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(2), 243–254.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36(4), 859–866.

Patwardhan, I., Hurley, K. D., Thompson, R. W., Mason, W. A., & Ringle, J. L. (2017). Child maltreatment as a function of cumulative family risk: Findings from the intensive family preservation program. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 92–99.

Pereda, N., & Díaz-Faes, D. A. (2020). Family violence against children in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic: a review of current perspectives and risk factors. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 14(1), 40.

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., Jemison, E., Kaukinen, C., & Knaul, F. M. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic-Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 74, 101806.

Rebellon, C. J., & Van Gundy, K. (2005). Can control theory explain the link between parental physical abuse and delinquency? A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 42(3), 247–274.

Reingle Gonzalez, J. M., Molsberry, R., Maskaly, J., & Jetelina, K. K. (2020). Trends in family violence are not causally associated with COVID-19 stay-at-home orders: A commentary on Piquero et al. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(6), 1100–1110.

Rodriguez, E., Lasch, K. E., Chandra, P., & Lee, J. (2001). Family violence, employment status, welfare benefits, and alcohol drinking in the United States: what is the relation? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55(3), 172–178.

Rosenfeld, R., Boxerman, B., & Lopez, E. (2022). Pandemic, social unrest, and crime in US cities: mid-year 2022 update. Council on Criminal Justice.

Rothman, E. F., Johnson, R. M., Young, R., Weinberg, J., Azrael, D., & Molnar, B. E. (2011). Neighborhood-level factors associated with physical dating violence perpetration: Results of a representative survey conducted in Boston MA. Journal of Urban Health, 88(2), 201–13.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing neighborhood effects: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 443–478.

Sapkota, D., Baird, K., Saito, A., & Anderson, D. (2019). Interventions for reducing and/or controlling domestic violence among pregnant women in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 8, 1–11.

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. University of Chicago Press.

Slavova, S., Rock, P., Bush, H. M., Quesinberry, D., & Walsh, S. L. (2020). Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 214, 108176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176

Spencer, C., Mallory, A. B., Cafferky, B. M., Kimmes, J. G., Beck, A. R., & Stith, S. M. (2019). Mental health factors and intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 9(1), 1.

Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Ribeaud, D., Murray, A. L., Hepp, U., Eisner, M., & Shanahan, L. (2021). Self-injury and domestic violence in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Trajectories, precursors, and correlates. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 560–575.

Stover, C. S., Urdahl, A., & Easton, C. (2012). Depression as a mediator of the association between substance abuse and negative parenting of fathers. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38, 344–349.

Testa, M., & Furstenberg, F. F. (2002). The social ecology of child endangerment. In A century of juvenile justice (pp. 237–263).

Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., Hamby, S. L., & Shattuck, A. (2013). Family structure, victimization, and child mental health in a nationally representative sample. Social Science & Medicine, 87, 39–51.

United States Census Bureau Quick Facts (2024). “Quick Facts.” Available from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/

U.S. Census Bureau (2021). American Community Survey (ACS). https://www.census.gov/programssurveys/acs/. Accessed 06/14/24.

Wahi, A., Zaleski, K. L., Lampe, J., Bevan, P., & Koski, A. (2019). The lived experience of child marriage in the United States. Social Work in Public Health, 34(3), 201–213.

Weisler, R., & Chrisman, A. (2020). Psychiatry perspectives on patient care in a post-pandemic world [Webinar]. PsychU.

Wisconsin Department of Justice. (n.d.). WI Bureau of Justice Information and Analysis (BJIA) WIBRS data. Retrieved from https://www.doj.state.wi.us/dles/bjia/wibrs-data

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it

World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report there are no conflict of interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, M.N., Konkel, R.H. Safer or Endangered at Home?: An Examination of Neighborhood Effects on Family Violence Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Safer-at-Home Order. Am J Crim Just (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-024-09772-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-024-09772-w