Abstract

A developing bioeconomy and the need for alternate sources of energy are promoting a more intensive procurement and use of forest biomass. While it is a fact that increased biomass harvesting generates greater nutrient losses from forest ecosystems relative to stem-only harvesting, the use of nutrient budget approaches as a decision support tool in managing forests under intensive biomass removal is uncommon. This lack of use can be explained by several factors including: large uncertainties in predicting certain fluxes, the poor representation of nutrient dynamics following harvest in nutrient cycling models, the lack of representation of biological feedback, the lack of appropriate validation, and finally the lack of maps of specific soil properties that would be required to predict nutrient budgets over forest landscapes. This review documents the impact of intensive biomass extraction on nutrient cycling and discusses the gaps in knowledge and the uncertainties associated with nutrient budgets. It identifies research and development issues that need to be resolved for making forest nutrient budgets more reliable and more useful to address the questions regarding the environmental sustainability of intensive biomass harvesting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the last few decades, the demand for biomass feedstocks for bioenergy production has increased sharply; forest biomassFootnote 1 not used by conventional wood product industries (e.g. sawtimber, pulp, fibreboard), such as logging residues (branches, tree tops), small trees or trees with defects, or non-commercial species is recognized as an important feedstock source [2, 3]. Also, coarse roots and stumps are in some regions considered as biomass feedstocks. A concern arising from the increased procurement of forest biomass is the potentially detrimental impacts that this additional harvest may have on soil productivity [4•]. Extracting more biomass from a given site increases nutrient losses out of the forest ecosystem. In addition, the biomass feedstock sources harvested for bioenergy production are generally richer in nutrients than wood fibre extracted for conventional wood products (i.e. tree boles) (Fig. 1). Consequently, as forest biomass is harvested more intensively, the nutrient export from the ecosystem per amount of biomass harvested also increases. An important question is therefore whether a given ecosystem can support this additional nutrient export.

A theoretical nutrient budget is defined as the algebraic balance between nutrient inputs and outputs of an ecosystem, integrated over a specified time period [5]: a forest management strategy that would yield a balanced nutrient budget (nutrient outputs ≤ inputs) would be considered as sustainable from the standpoint of soil fertility. An enhancement of harvest intensity where tree tops, branches and stumps are removed in addition to tree boles could shift the nutrient balance to a deficit [6•, 7, 8]. Harvest intensification coupled with acidic atmospheric deposition has promoted interest in the use of nutrient budgets to evaluate the sustainability of forest management practices [9–11].

Maintaining a nutrient balance is foundational to sustainable forestry, and there is an abundance of studies using nutrient budgets in the scientific literature. However, best management practices (BMPs), regulations and guidelines for sustainable forest biomass procurement rarely rely strictly on nutrient budgets [12–15]. Rather, decision-making is most often based on empirically derived indicators of site sensitivity/suitability to intensive biomass removal, such as soil properties indicative of sites that may be of concern, for example, sites with wet or thin soils, steep slopes or low organic matter content [16, 17•].

Should nutrient budgets be more widely used to guide forest management activities involving biomass harvesting? In the following discussion, we will cover the implications of intensive biomass harvesting for site nutrient budgets, the caveats and knowledge gaps that may need to be addressed to make the nutrient budget approach more appropriate and useful to guide forest management. Most reviewed studies came from boreal and temperate biomes; however, the general conclusions should apply to other regions as well.

Analysis

What is the increase in extracted nutrients as a result of intensive biomass harvesting?

Nutrient concentrations vary with tree species and tree parts. Biomass composed of small stems or branches or foliage will show greater nutrient concentrations than that of boles or of stumps. The analysis of the extensive database compiled in Paré et al. [18] indicated that the greatest variability in nutrient concentrations of tree tissue rested between genera, whereas considering species did not further improve the precision of the estimates.

Typical operations of logging residue recovery after clear-cut in the boreal and temperate biomes remove about 50 % of the original amount of logging residues present on site; however, it was found to vary from 4 to 89 % with the highest values found in Nordic countries due to better adapted equipment and trained workforce [19]. Figure 2 illustrates the average increase in nutrient export (relative to stem-only harvesting) when 50 % of branches and foliage are removed in addition to tree boles for softwood and hardwood stands in Canada. When only branches are harvested (e.g. if logging residues are left to dry on site for one season, which allows foliage to shed and remain on site), the increase in loss of elements is around 30 % compared with the harvest for boles only, with phosphorus (P) losses being slightly higher at 40 %. When foliage is removed as well, the losses greatly increase. This is especially apparent for P and nitrogen (N) in softwood stands: harvesting half of the branch and foliage residues would more than double the extraction of N and P as compared with stem-only harvesting. A review of the impact of whole-tree harvesting studies [17•] indicated that reduced soil P availability following whole-tree harvesting compared with stem-only harvesting had been observed in a high proportion of studies. Impacts on soil N were less apparent; most significant reductions following residue removal were found only in the organic soil layers.

Increased nutrient losses in harvested products (% increase from the harvest of boles and bark) caused by biomass harvesting considering that half of the branches are harvested (BR (0.5)) or half of the branches and half of the foliage are harvested (Br + F (0.5)). A 50 % residue harvest intensity is used as it is the mean value found in a data compilation from the boreal and temperate regions [19]. Values are averages for deciduous and coniferous commercial tree species in Canada as derived from Paré et al. [18] assuming a basal area of 20 m2 ha−1 for softwoods and 25 for hardwoods

Can nutrient inputs compensate for nutrient losses?

Investigating nutrient balance is not a simple task as there is no universal standardized methodology for estimating nutrient inputs to the system. Sources of inputs vary according to elements: N comes mainly from the atmosphere, whereas P and base cations (i.e. calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), potassium (K)) are generally mainly supplied by mineral weathering. Most nutrient budgets suppose a steady state in nutrient input rates, i.e. static mass balances where nutrient fluxes are integrated over a specified time and are therefore constant over that period [5]. Issues with this assumption are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen (N) is the nutrient that most often limits forest productivity [20, 21] as fertilization trials have revealed in the boreal and temperate regions [22, 23]. N inputs stimulate growth in a majority of forest ecosystems [24]. It is therefore of crucial relevance to determine its balance in nutrient budgets. Atmospheric wet/dry depositions and biotic/abiotic fixation are the main sources of N inputs to the forest ecosystems [20]. Several studies have indicated that in some regions, for example, southern Sweden or northeastern North America, N atmospheric depositions are generally sufficient to compensate for harvest-induced N losses even when including removal of harvest residues (Fig. 3) [25, 26, 27•]. However, in other regions, for example, northern Sweden, Finland or western North America, atmospheric N depositions would not be sufficient [25, 28–31]. Furthermore, N inputs from precipitation have dropped significantly over the last few decades in several regions of Europe and northeastern North America.

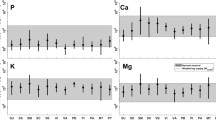

Stock removed per harvest (dark column) compared with atmospheric deposition (light column). Stock removed as in Fig. 2: average softwood (SW, 20 m2 ha−1 basal area) and hardwood (HW, 25 m2 ha−1 basal area) stands from Canada extracted from Paré et al. [18]. 1 refers to bole + bark; 2 refers to stem, bark + 50 % of branches and foliage. Maximal and minimal rates of atmospheric deposition (annual rates × 60 years): from Lequy et al. [84] for Europe (Eur-H, Eur-L) with the exception of N that comes from Binkley, Högberg [85]. Values from Vadeboncoeur et al. [27•] are used for the northeastern USA (NE-US) and values from Hazlett et al. [26] for northern Ontario (Ont)

For its part, nitrogen fixation is often a neglected component of nutrient budgets. Apart from N-fixing plants, N fixation by free-living organisms is ubiquitous but spatial and temporal variability of the rates of this process is poorly documented. Because N fixation is an energy-consuming process, N-fixing organisms perform better in an environment where N is limited. This situation creates feedback in the N cycle that may be responsible for homeostasis in N availability [32], in which greater N availability reduces N fixation.

The large reservoir of soil organic nitrogen, most of which is contained in organic or organo-mineral compounds that are recalcitrant to heterotrophic decomposition, constitutes another source of N because mycorrhizal fungi (fungi living in a symbiotic interaction with plant roots), especially ecto-mycorrhizae (EM), can mine this reservoir [33]. Although such a reservoir is finite, it is large in comparison with ecosystem losses in harvested products (i.e. typically 10 to 20 times the amount in harvested wood products including biomass [26, 27•]). Feedback mechanisms between N and P plant demand and acquisition have been documented. For example, EM species with a high capacity to mine organic matter for N usually decline when availability of inorganic N increases [34]. N fertilization or elevated N atmospheric deposition usually result in slow EM growth since the plant carbon allocation will be diverted away from belowground and will be used instead to incorporate inorganic N into amino acids to enhance aboveground shoot growth [35]. Conversely, it has been shown that deficiency of N and/or P enhances belowground carbon allocation and EM growth [36]. While acquisition of N is energy consuming and would involve a transfer of carbon and energy from the plant to its root symbionts, this process may nevertheless reduce the impact of increased N export through biomass removal on N availability in forest systems.

These examples suggest that feedback loops exist within forest ecosystems and influence nutrient cycling: geochemical N inputs through N fixation and biogeochemical inputs through organic N mining can be enhanced by N deficiency. Greater nutrient inputs, as a result of nutrient deficiency induced by greater nutrient export in wood products could, at least partly, cancel an expected nutrient budget deficit such as illustrated in Fig. 4. However, these processes have yet to be taken into consideration in nutrient cycling models and budgets; a better quantification of these mechanisms is therefore needed. Also, if these mechanisms come into effect, while they may help to maintain plant nutrition, they would trigger an additional allocation of resources belowground, potentially to the detriment of forest productivity. Again, this has not been quantified. Johnson, Turner [37] also report cases of ‘occult’ N inputs into forest ecosystems, i.e. where apparent net increments of ecosystem N exceed known N inputs; authors attribute these occult N sources to poorly assessed/quantified inputs from dry deposition, non-symbiotic N fixation, and weathering of N from sedimentary rocks, highlighting the need for a better understanding of N processes and cycling.

Simplified conceptual model of nutrient cycling. Red arrows represent direct impact of increased biomass harvesting (more export, less inputs to the soil following harvesting). Green arrows represent potential feedback in nutrient cycling where greater inputs are stimulated by nutrient deficiencies (see text for details). These additional inputs could at least in part compensate for greater losses and are generally not accounted for in nutrient budgets. The orange box and arrow indicate critical elements for the maintenance of soil fertility that are often neglected in nutrient budget approaches (rapid vegetation recovery following harvesting as well as the maintenance of good soil conditions, for example, by avoiding erosion or compaction contributes to maintaining nutrient pools and cycling). CEC cation exchange capacity, provided by fine particles and organic matter

Cations and phosphorus

Contrary to N, atmospheric inputs of base cations (Ca, Mg, K) and P are generally small relative to losses in harvested products (Fig. 3) [26, 27•]. Mineral weathering plays an important role in their supply and is therefore an important input to their budget. Although several methods can be used to provide estimates of mineral weathering, they are fraught with uncertainties [38, 39] and a comparison of different methods shows that there can be large variability in weathering estimates. For example, Klaminder et al. [40] and Lucas et al. [41] found that variability in estimates, calculated for forested catchments in Sweden, was too high to determine whether harvest residue removal would shift the catchment nutrient budget to a deficit. A similar conclusion was reached by Johnson et al. [42] in Ireland where the high uncertainties did not make it possible to distinguish the impact of harvest residue removal from conventional stem-only harvesting on the cation balance. In both studies, the increased nutrient export caused by residue removal was considerably smaller than the uncertainties associated with estimates of mineral weathering rates, preventing the use of the nutrient budget for decision-making.

Two other issues further cast doubt on estimates of mineral weathering fluxes. Most methods are calibrated at the watershed scale and estimate mineral weathering rates over long time periods. Rates of soil mineral weathering are mostly derived from approaches that consider the soil as a homogeneous matrix in which weathering is a constant flux over time (driven by soil solution equilibrium reactions in the process-based approaches), and are calibrated at the watershed scale [43]. They do not consider the fine-scale mining of weathering processes nor the fact that mineral weathering could be, to some extent, demand-driven. This debate is a controversial subject that is discussed in [44] and [45]. Conversely, a growing body of literature suggests that EM as well as arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi [46] together with associated bacteria have the capacity to mine mineral surfaces for nutrients and that this capacity is enhanced by nutrient limitation; in that case, mineral weathering should be presented as a dynamic process. Plants have been found to invest more energy in their fungal symbionts under nutrient limitation, and the fungal transport of photosynthate-derived carbon towards patches of nutrient-rich mineral grains has been observed [47]. Rock dissolution and tunnelling of mineral grains, notably of apatite, a Ca- and P-containing mineral, have been found to occur under both ectomycorrhizae and arbuscular mycorrhizae [48–50]. Fungal-mediated weathering of K- and Mg-bearing minerals such as biotite has also been observed [51–53]. This suggests positive feedback between plant nutrient requirements and mineral weathering rates. The importance of such a demand-driven process would considerably change the outcome of nutrient budgets. For example, Vadeboncoeur et al. [27•] reported that the amount of P removed in harvested products of New England forest stands on granitic bedrock was estimated at 20 kg ha−1. The soil supply in extractable P was estimated at values that varied between 38 and 194 kg ha−1; the P content found in apatite in the B soil horizon was estimated to range from 61 to 850 P kg ha−1 whereas the top 25 cm of the C horizon (in which mineral weathering is assumed to be minimal) was estimated to contain 0 to 2500 kg ha−1 P (a zero value is found for shallow soils with no C or no apatite). If these mineral P resources are considered to be potentially available to plant nutrition, this could lead to positive P budgets for forest stands for several harvest rotations, depending on the abundance of such minerals in the soil.

As shown above, positive feedback has been documented between plant demand in N and P, and the mining of soil organic N and mineral apatite for P and Ca (Fig. 4) both at the fine scale [47] as well as the ecosystem scale. For example, Yanai et al. [54] observed more Ca in exchangeable form in young fast-growing and nutrient-demanding stands than in old stands, while a steady-state nutrient weathering rate (as assumed in nutrient budgets) should have caused the opposite trend. Also, Bélanger et al. [55] observed greater exchangeable Ca in soils of fast-growing tree provenances than in slow-growing ones. It is unclear whether deficiencies in other elements, such as K or Mg, would also trigger greater weathering at the mineral-root interface. Ericsson [36] documented impaired carbon loading into the phloem when Mg is in short supply: this could lead to negative feedback between plant nutrient demand and plant capacity to acquire nutrients, which would mean that the capacity of the forest ecosystem to reverse a Mg deficiency could be difficult and that fertilization could be required.

Dynamics of harvest residues in the soil-plant system: more than a simple balance sheet

Dynamics of nutrient cycling

Another aspect often neglected in nutrient budgets is the availability and cycling of nutrients contained in harvest residues. It is often assumed that all nutrients stocked in harvest residues and released upon decomposition and mineralization of residues will contribute to soil-available nutrient reserves and to plant nutrition. However, recovery rates (in terms of the amount of nutrients available in the soil-plant system, relative to the original amount contained in harvest residues) were found to be generally high for Ca and Mg (above 40 %), but low for K (0–15 %) [56], an element that easily leaches out of the soil profile as reported in Thiffault et al. [17•]. Another study [57] suggested that very acidic mineral soil layers, whose cation exchange sites are saturated with exchangeable aluminum (Al), would have a very limited capacity to capture and conserve base cations released from decomposing harvest residues: exchangeable Al is difficult to displace from exchange sites notably due to its high valence. On the other hand, soil layers with low concentrations of exchangeable Al, such as organic layers, can more easily acquire and conserve released base cations.

Therefore, field studies following up on the fate of nutrients from harvest residues over time are suggesting that contrary to what is expected in static nutrient budgets, the capacity of the soil-plant system to retain nutrients that are released upon the decomposition and mineralization of harvest residues is not 100 % and largely depends on the nutrient, soil and vegetation conditions. This therefore implies that nutrient budgets of a forest system are more complex than a simple geochemical accounting of nutrient gains and losses. The capacity of the soil-plant system to retain and cycle nutrients may have a great influence on the actual benefits of maintaining residues on the site, perhaps more so than the actual amounts of nutrients leaving the system in harvested products. Figure 5 shows the theoretical pattern of nutrient immobilization in a growing stand. Immobilization is maximal at canopy closure, after which nutrient recycling in the tree and in the soil-tree systems becomes more efficient [58•]. Following harvesting, there is generally a flush of nutrients (the Assart effect [59]) due to a greater input of litter, a lower plant uptake and often a faster decomposition/mineralization of the litter and forest floor. This flush may, or may not, be in synchronicity with plant and soil immobilization rates, depending on the nutrient (Fig. 5). For example, the rapid flush of K leached out of harvest residues may quickly leave the system without accumulation in soil or plant pools (e.g. [60]) while the slower release of N [61] may provide better synchronicity and retention within the plant-soil system. The fact that residues are often not evenly distributed on the harvest area [62], but often concentrated in skidding roads or in piles across the cutblock, might also influence the capacity of the plant-soil system to efficiently recover their nutrient content.

Theoretical rate of nutrient immobilization in a growing stand together with patterns of nutrient release from decomposing harvest residues remaining on site. Poor synchronicity may be found for K, an element that rapidly leaches out of organic material, while the good synchronicity curve may be more typical of N or P, elements that are released after considerable processing by heterotrophic microbial communities

Static nutrient budgets therefore fail to encompass the specific dynamics of debris decomposition. Moreover, in terms of dynamics, Smolander et al. [63] documented how the release of terpenes and phenolic compounds from harvest residues may stimulate soil C and N cycling by providing a source of C to microbial populations. An increase in enzymatic activities involved in N, C and P transformations has also been linked to the amount of harvest residues retained on site [64].

In summary, the beneficial effect of maintaining slash for plant nutrition may be overestimated by nutrient budgets if they assumed that all nutrients retained in slash are contributing to the soil-available pool and if they ignore biological feedback mechanisms. As pointed out by Zetterberg et al. [65•], large nutrient depletions predicted by nutrient budgets have almost systematically failed to be observed in empirical, field-based studies. However, introducing these processes in modelling may be challenging.

Non-nutrient-related effects of harvest residues

Despite these findings related to nutrient cycling, several studies have shown that the effect of harvest residues on tree productivity in the first years following harvest was mostly related to the physical effects of residues on the soil environment, and not to nutritional changes. For example, at a very early stage of stand development, the presence of residues on site may increase light and water availability for tree seedlings because of the inhibition of competing vegetation cover [66–70]. Soil water availability may also be affected through the sheltering effect of residues that limits evaporation but intercepts precipitation [69] especially when residues are not mixed into the soil by site preparation. Apart from competing vegetation and soil water, logging residues can affect planting microsites by decreasing soil temperature [70–72]; on sites with already short growing seasons, this can hamper seedling physiology and growth. Proe, Dutch [73] suggested that the impacts of residues on microclimate and competition control should be visible shortly after planting; when a stand approaches crown closure (e.g. 8–12 years after planting in the boreal climate), effects of removal of logging residues on soil and tree nutrition could become more apparent [74]. However, 10 years after harvest and stand establishment, Smolander et al. [75] found little correlation between the response to harvest residues of soil (chemical and biological) properties and tree growth. The authors suggested that some non-nutrient factor brought about by the residues, such as changes in soil physical conditions, was still driving the response of trees to residue retention, even 10 years after stand establishment.

These results underline the fact that the actual response of the forest ecosystem to the presence/absence of residues may only be loosely related to the retention/export of nutrients caused by harvesting methods: forest biogeochemical cycling and tree productivity appear to be driven by more complex factors and interactions than simple nutrient inputs-outputs at least in the short-term window provided by experimentation (which admittedly has yet to cover a complete rotation). Nutrient outflow could still become the main driver of ecosystem functioning after one or several rotations. It is also interesting to note that removal of harvest residues at thinning has been found to have negative impacts on subsequent growth of the remaining trees [76]; the important retention of forest cover during thinning probably lessens any microclimatic effects that the maintenance of residues often have in clear-cuts, and nutrient availability might be the overriding driver of tree growth at the stage of the rotation when thinning occurs. Nevertheless, it would be important to correctly interpret the impact of biomass harvesting by taking into consideration non-nutritional effects on nutrient budget studies.

Conclusion

Critical loads of acidity, which are budgets with inputs and outputs of acidity, have been successful at linking up science and policymaking for the control of atmospheric pollution and their potential deleterious effects on water and forest ecosystems. The reasons for this success are the fact that input-output calculations are intuitive and relatively easy to understand, they are easy to calculate, and the results from calculations could be readily translated into policies such as air pollution abatement strategies [77]. Therefore, because increased biomass harvesting causes greater nutrient loss, a nutrient balance approach to determine conditions (site type and intensity of removal) where such practices would be environmentally sustainable or detrimental appears logical; it might be an interesting preliminary step in interfacing scientific assessment of sustainability of forest practices with policymaking. The concept of ecological rotation is a good summary of this idea [5]. Moreover, nutrient budgets make it possible to predict nutrient balance at the end of one or several rotations, whereas most field studies on biomass harvesting in the boreal and temperate biomes have been in place for only a few decades and therefore only cover short- to medium-term effects [65•]. However, the nutrient budget approach has several important limitations as discussed here. In particular, it is prone to large uncertainties for several nutrient fluxes, it generally ignores ecosystem feedback mechanisms that are very common in natural forest systems, and it ignores key drivers of geochemical and biogeochemical cycling and tree productivity. Nutrient budgets may be more readily adapted to conditions of intensively managed short-rotation plantations that are closer to agricultural systems, in which nutrient inputs/outputs and cycling are somewhat simpler to assess. For example, nutrient budgets have provided a useful methodological template for nutrient management in coppice forests [78]. However, nutrient budgets appear to be inadequate for capturing the complexity of most forest systems, especially long-rotation systems such as found in the boreal and temperate biomes. Furthermore, the nutrient budget approach has undergone very little validation.

Validation is a prerequisite to the use of models to guide ecosystem management. Interestingly, one example of empirical field validation of predictions made by theoretical nutrient budgets has shown that contrary to budget predictions from Johnson et al. [79], leaching losses and uptake by regenerating vegetation did not deplete soil-exchangeable Ca pools within 15 years of harvesting of boles, branches and tree tops of mixed oak stands [80]. Here, it may be pertinent to quote Aber [81] from his well-known note entitled “Why don’t we believe the models?”: “Perhaps the greatest dis-service ecologists can provide comes from allowing… unvalidated models to be used to predict the results of policy actions. It is equivalent to basing policy decisions on data we know to be seriously flawed. It also fosters the false impression that we know more than we do about the systems we study, which is then often in contradiction to what the experimental data suggest”.

Given the large uncertainties of the nutrient budget approach, and the fact that it fundamentally lacks the dynamic aspects of soil-plant interactions, it appears prudent to build confidence with the empirical evidence related to biomass harvesting provided by sound experimental designs such as the North American Long-Term Soil Productivity (LTSP) project [66] and to promote the widespread use of monitoring [82, 83] as well as a better integration of models with observations as they become available. Nevertheless, as part of a scientific approach that includes modelling, empirical validation with field studies and further improvement of model assumptions, nutrient budget models remain a useful tool to identify knowns and unknowns in the biogeochemistry of forest ecosystems.

Notes

In the following text, the term “biomass” will be used in reference to the biomass that is harvested in addition to the conventional harvest of boles. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses this term in a much broader sense: “Organic material both aboveground and belowground, and both living and dead, e.g. trees, crops, grasses, tree litter, roots etc. Biomass includes the pool definition for above-and below-ground biomass” [1]. In forestry, the term is context dependent as un-used tree species, woody parts with a smaller diameter than what is considered commercial, as well as other tree parts such as stumps vary in definition depending on forest type, uses and regulations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

IPCC. Good practice guidance for land use, land-use change and forestry. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2003

Smeets EM, Faaij AP, Lewandowski IM, Turkenburg WC. A bottom-up assessment and review of global bio-energy potentials to 2050. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2007;33(1):56–106.

Lauri P, Havlík P, Kindermann G, Forsell N, Böttcher H, Obersteiner M. Woody biomass energy potential in 2050. Energy Policy. 2014;66:19–31. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.11.033.

Lamers P, Thiffault E, Paré D, Junginger M. Feedstock specific environmental risk levels related to biomass extraction for energy from boreal and temperate forests. Biomass Bioenergy. 2013;55(8):212–26. This paper provides a broad overview of the environmental issues concerning the extraction of forest biomass.

Ranger J, Turpault M-P. Input-output nutrient budgets as a diagnostic tool for sustainable forest management. For Ecol Manage. 1999;122(1–2):139–54. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00038-9.

Achat D, Deleuze C, Landmann G, Pousse N, Ranger J, Augusto L. Quantifying consequences of removing harvesting residues on forest soils and tree growth—a meta-analysis. For Ecol Manage. 2015;348:124–41. This paper provides a recent meta-analysis on the impact of harvesting forest residues on soils and tree growth.

Augusto L, Achat DL, Bakker MR, Bernier F, Bert D, Danjon F, et al. Biomass and nutrients in tree root systems—sustainable harvesting of an intensively managed Pinus pinaster (Ait.) planted forest. GCB Bioenergy. 2015;7(2):231–43. doi:10.1111/gcbb.12127.

Vangansbeke P, De Schrijver A, De Frenne P, Verstraeten A, Gorissen L, Verheyen K. Strong negative impacts of whole tree harvesting in pine stands on poor, sandy soils: a long-term nutrient budget modelling approach. For Ecol Manage. 2015;356:101-11. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.07.028.

Duchesne L, Houle D. Impact of nutrient removal through harvesting on the sustainability of the boreal forest. Ecol Appl. 2008;18(7):1642–51. doi:10.2307/40062239.

Iwald J, Löfgren S, Stendahl J, Karltun E. Acidifying effect of removal of tree stumps and logging residues as compared to atmospheric deposition. For Ecol Manage. 2013;290:49–58. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.06.022.

Akselsson C, Westling O, Sverdrup H, Holmqvist J, Thelin G, Uggla E, et al. Impact of harvest intensity on long-term base cation budgets in Swedish forest soils. Water Air Soil Pollut: Focus. 2007;7(1-3):201–10. doi:10.1007/s11267-006-9106-6.

Roach J, Berch SM. A compilation of forest biomass harvesting and related policy in Canada. 2014 Contract No.: 081.

Evans AM, Perschel RT, Kittler BA. Overview of forest biomass harvesting guidelines. J Sustain For. 2012;32(1-2):89–107. doi:10.1080/10549811.2011.651786.

Stupak I, Asikainen A, Röser D, Pasanen K. Review of recommendations for forest energy harvesting and wood ash recycling. In: Röser D, Asikainen A, Raulund-Rasmussen K, Stupak I, editors. Sustainable Use of Forest Biomass for Energy. Springer Netherlands: Managing Forest Ecosystems; 2008. p. 155–96.

Abbas D, Current D, Phillips M, Rossman R, Hoganson H, Brooks KN. Guidelines for harvesting forest biomass for energy: a synthesis of environmental considerations. Biomass Bioenergy. 2011;35(11):4538–46. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2011.06.029.

Nave LE, Vance ED, Swanston CW, Curtis PS. Harvest impacts on soil carbon storage in temperate forests. For Ecol Manage. 2010;259(5):857–66.

Thiffault E, Hannam KD, Paré D, Titus BD, Hazlett PW, Maynard DG, et al. Effects of forest biomass harvesting on soil productivity in boreal and temperate forests—a review. Environ Rev. 2011;19(NA):278–309. A thorough review of published literature on the effects of forest biomass harvesting on soil, tree nutrition and tree growth.

Paré D, Bernier P, Lafleur B, Titus BD, Thiffault E, Maynard DG, et al. Estimating stand-scale biomass, nutrient contents, and associated uncertainties for tree species of Canadian forests. Can J For Res. 2013;43(7):599–608. doi:10.1139/cjfr-2012-0454.

Thiffault E, Béchard A, Paré D, Allen D. Recovery rate of harvest residues for bioenergy in boreal and temperate forests: a review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev: Energy Environ. 2014;4(5):429–51.

Boring L, Swank W, Waide J, Henderson G. Sources, fates, and impacts of nitrogen inputs to terrestrial ecosystems: review and synthesis. Biogeochem. 1988;6(2):119-59.

Vitousek PM, Howarth RW. Nitrogen limitation on land and in the sea—how can it occur. Biogeochemistry. 1991;13(2):87–115.

Maynard DG, Paré D, Thiffault E, Lafleur B, Hogg KE, Kishchuk B. How do natural disturbances and human activities affect soils and tree nutrition and growth in the Canadian boreal forest? Environ Rev. 2014;22(2):161–78. doi:10.1139/er-2013-0057.

Magnani F, Mencuccini M, Borghetti M, Berbigier P, Berninger F, Delzon S, et al. The human footprint in the carbon cycle of temperate and boreal forests. Nature. 2007;447(7146):849–51. doi:10.1038/nature05847.

Vitousek PM, Aber JD, Howarth RW, Likens GE, Matson PA, Schindler DW, et al. Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: sources and consequences. Ecol Appl. 1997;7(3):737–50.

Akselsson C, Westling O. Regionalized nitrogen budgets in forest soils for different deposition and forestry scenarios in Sweden. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2005;14(1):85–95. doi:10.1111/j.1466-822X.2004.00137.x.

Hazlett PW, Morris DM, Fleming RL. Effects of biomass removals on site carbon and nutrients and jack pine growth in boreal forests. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2014;78(S1):S183–95. doi:10.2136/sssaj2013.08.0372nafsc.

Vadeboncoeur MA, Hamburg SP, Yanai RD, Blum JD. Rates of sustainable forest harvest depend on rotation length and weathering of soil minerals. For Ecol Manage. 2014;318:194–205. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2014.01.012. This study provides good examples of how assumptions on nutrient cycling rates can change the evaluation of the sustainability of forest harvesting.

Rolff C, Ågren GI. Predicting effects of different harvesting intensities with a model of nitrogen limited forest growth. Ecol Model. 1999;118(2–3):193–211. doi:10.1016/S0304-3800(99)00043-5.

Aherne J, Posch M, Forsius M, Lehtonen A, Härkönen K. Impacts of forest biomass removal on soil nutrient status under climate change: a catchment-based modelling study for Finland. Biogeochemistry. 2012;107(1-3):471–88. doi:10.1007/s10533-010-9569-4.

Himes AJ, Turnblom EC, Harrison RB, Littke KM, Devine WD, Zabowski D, et al. Predicting risk of long-term nitrogen depletion under whole-tree harvesting in the coastal Pacific Northwest. For Sci. 2014;60(2):382–90. doi:10.5849/forsci.13-009.

Merilä P, Mustajärvi K, Helmisaari H-S, Hilli S, Lindroos A-J, Nieminen TM, et al. Above- and below-ground N stocks in coniferous boreal forests in Finland: implications for sustainability of more intensive biomass utilization. For Ecol Manage. 2014;311:17–28. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2013.06.029.

Gundale MJ, Deluca TH, Nordin A. Bryophytes attenuate anthropogenic nitrogen inputs in boreal forests. Glob Chang Biol. 2011;17(8):2743–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02407.x.

Chapman SK, Langley JA, Hart SC, Koch GW. Plants actively control nitrogen cycling: uncorking the microbial bottleneck. New Phytologist. 2006;169(1):27–34. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01571.x.

Taylor AFS, Martin F, Read DJ. Fungal diversity in ectomycorrhizal communities of Norway spruce [Picea abies (L.) Karst.] and beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) along north-south transects in Europe. In: Schulze E-D, editor. Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in European Forest Ecosystems. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Ecological Studies; 2000. p. 343–65.

Wallander H. A new hypothesis to explain allocation of dry matter between mycorrhizal fungi and pine seedlings in relation to nutrient supply. In: Nilsson LO, Hüttl RF, Johansson UT, editors. Nutrient uptake and cycling in forest ecosystems. Springer Netherlands: Developments in Plant and Soil Sciences; 1995. p. 243–8.

Ericsson T. Growth and shoot: root ratio of seedlings in relation to nutrient availability. In: Nilsson LO, Hüttl RF, Johansson UT, editors. Nutrient uptake and cycling in forest ecosystems. Springer Netherlands: Developments in Plant and Soil Sciences; 1995. p. 205–14.

Johnson DW, Turner J. Nitrogen budgets of forest ecosystems: a review. For Ecol Manage. 2014;318:370–9. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2013.08.028.

Simonsson M, Bergholm J, Olsson BA, Brömssen CV, Oborn I. Estimating weathering rates using base cation budgets in a Norway spruce stand on podzolised soil: analysis of fluxes and uncertainties. For Ecol Manage. 2015;340:135–52. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2014.12.024.

Futter MN, Klaminder J, Lucas RW, Laudon H, Köhler SJ. Uncertainty in silicate mineral weathering rate estimates: source partitioning and policy implications. Environ Res Lett. 2012;7(2):024025.

Klaminder J, Lucas RW, Futter MN, Bishop KH, Köhler SJ, Egnell G, et al. Silicate mineral weathering rate estimates: are they precise enough to be useful when predicting the recovery of nutrient pools after harvesting? For Ecol Manage. 2011;261(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.040.

Lucas RW, Holmström H, Lämås T. Intensive forest harvesting and pools of base cations in forest ecosystems: a modeling study using the Heureka decision support system. For Ecol Manage. 2014;325:26–36. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2014.03.053.

Johnson J, Aherne J, Cummins T. Base cation budgets under residue removal in temperate maritime plantation forests. For Ecol Manage. 2015;343:144–56. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.01.022.

Augustin F, Houle D, Gagnon C, Courchesne F. Long-term base cation weathering rates in forested catchments of the Canadian Shield. Geoderma. 2015;247–248:12–23. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.01.016.

Rosling A, Finlay RD, Gadd GM. Geomycology. Fungal Bio Rev. 2009;23(4):91–3. doi:10.1016/j.fbr.2010.03.005.

Finlay R, Wallander H, Smits M, Holmstrom S, van Hees P, Lian B, et al. The role of fungi in biogenic weathering in boreal forest soils. Fungal Biology Rev. 2009;23(4):101–6. doi:10.1016/j.fbr.2010.03.002.

Taktek S, Trépanier M, Servin PM, St-Arnaud M, Piché Y, Fortin JA, et al. Trapping of phosphate solubilizing bacteria on hyphae of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis DAOM 197198. Soil Biol Biochem. 2015;90:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.07.016.

Smits MM, Bonneville S, Benning LG, Banwart SA, Leake JR. Plant-driven weathering of apatite—the role of an ectomycorrhizal fungus. Geobiology. 2012;10(5):445–56. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4669.2012.00331.x.

Dickie I, Martínez-García L, Koele N, Grelet GA, Tylianakis J, Peltzer D, et al. Mycorrhizas and mycorrhizal fungal communities throughout ecosystem development. Plant Soil. 2013;367(1-2):11–39. doi:10.1007/s11104-013-1609-0.

Koele N, Dickie IA, Blum JD, Gleason JD, de Graaf L. Ecological significance of mineral weathering in ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal ecosystems from a field-based comparison. Soil Biol Biochem. 2014;69:63–70. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.10.041.

Dickie IA, Koele N, Blum JD, Gleason JD, McGlone MS. Mycorrhizas in changing ecosystems. Botany. 2014;92(2):149–60. doi:10.1139/cjb-2013-0091.

Lian B, Wang B, Pan M, Liu C, Teng HH. Microbial release of potassium from K-bearing minerals by thermophilic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2008;72(1):87–98. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2007.10.005.

Balogh-Brunstad Z, Keller CK, Dickinson JT, Stevens F, Li CY, Bormann BT. Biotite weathering and nutrient uptake by ectomycorrhizal fungus, Suillus tomentosus, in liquid-culture experiments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2008;72(11):2601–18. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2008.04.003.

Bonneville S, Smits MM, Brown A, Harrington J, Leake JR, Brydson R, et al. Plant-driven fungal weathering: early stages of mineral alteration at the nanometer scale. Geology. 2009;37(7):615–8. doi:10.1130/g25699a.1.

Yanai RD, Blum JD, Hamburg SP, Arthur MA, Nezat CA, Siccama TG. New insights into calcium depletion in northeastern forests. J For. 2005;103(1):14–20.

Bélanger N, Paré D, Bouchard M, Daoust G. Is the use of trees with superior growth a threat to soil nutrient availability? A case study with Norway spruce. Can J For Res. 2004;34(3):560–72. doi:10.1139/x03-216.

Olsson BA, Bengtsson J, Lundkvist H. Effects of different forest harvest intensities on the pools of exchangeable cations in coniferous forest soils. For Ecol Manage. 1996;84(1–3):135–47. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(96)03730-9.

Bélanger N, Paré D, Yamasaki SH. The soil acid-base status of boreal black spruce stands after whole-tree and stem-only harvesting. Can J Forest Res. 2003;33(10):1874–9. doi:10.1139/x03-113.

Paré D, Markewitz D, Wallander H. Biogeochemical cycling. In: Peh KS-H, Corlett RT, Bergeron Y, editors. Routledge handbook of forest ecology. London 2015. p. 327-40. This book chapter provides an introduction to nutrient cycling in forest ecosystems.

Kimmins H. Balancing act: environmental issues in forestry. 2nd ed. Vancouver, BC, Canada: UBC Press; 1992.

Thiffault E, Paré D, Bélanger N, Munson A, Marquis F. Harvesting intensity at clear-felling in the boreal forest. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2006;70(2):691–701. doi:10.2136/sssaj2005.0155.

Brais S, Paré D, Lierman C. Tree bole mineralization rates of four species of the Canadian eastern boreal forest: implications for nutrient dynamics following stand-replacing disturbances. Can J For Res. 2006;36(9):2331–40. doi:10.1139/x06-136.

McCavour MJ, Paré D, Messier C, Thiffault N, Thiffault E. The role of aggregated forest harvest residue in soil fertility, plant growth, and pollination services. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2014;78:S196–207. doi:10.2136/sssaj2013.08.0373nafsc.

Smolander A, Kitunen V, Kukkola M, Tamminen P. Response of soil organic layer characteristics to logging residues in three Scots pine thinning stands. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;66:51–9. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.06.017.

Adamczyk B, Adamczyk S, Kukkola M, Tamminen P, Smolander A. Logging residue harvest may decrease enzymatic activity of boreal forest soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2015;82:74-80. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.12.017.

Zetterberg T, Köhler SJ, Löfgren S. Sensitivity analyses of MAGIC modelled predictions of future impacts of whole-tree harvest on soil calcium supply and stream acid neutralizing capacity. Sci Total Environ. 2014;494–495:187–201. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.114. This study contains a good discussion on modelled versus empirical data with respect to soil calcium cycling.

Ponder F, Fleming RL, Berch S, Busse MD, Elioff JD, Hazlett PW, et al. Effects of organic matter removal, soil compaction and vegetation control on 10th year biomass and foliar nutrition: LTSP continent-wide comparisons. For Ecol Manage. 2012;278:35–54.

Harrington TB, Slesak RA, Schoenholtz SH. Variation in logging debris cover influences competitor abundance, resource availability, and early growth of planted Douglas-fir. For Ecol Manage. 2013;296:41–52.

Holub SM, Terry TA, Harrington CA, Harrison RB, Meade R. Tree growth ten years after residual biomass removal, soil compaction, tillage, and competing vegetation control in a highly-productive Douglas-fir plantation. For Ecol Manage. 2013;305:60–6.

Roberts SD, Harrington CA, Terry TA. Harvest residue and competing vegetation affect soil moisture, soil temperature, N availability, and Douglas-fir seedling growth. For Ecol Manage. 2005;205(1–3):333–50. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2004.10.036.

Trottier-Picard A, Thiffault E, DesRochers A, Paré D, Thiffault N, Messier C. Amounts of logging residues affect planting microsites: a manipulative study across northern forest ecosystems. For Ecol Manage. 2014;312:203–15.

Proe MF, Griffiths JH, McKay HM. Effect of whole-tree harvesting on microclimate during establishment of second rotation forestry. Agric For Meteorol. 2001;110(2):141–54. doi:10.1016/S0168-1923(01)00285-4.

Zabowski D, Java B, Scherer G, Everett RL, Ottmar R. Timber harvesting residue treatment: Part 1. Responses of conifer seedlings, soils and microclimate. For Ecol Manage. 2000;126(1):25–34. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00081-X.

Proe MF, Dutch J. Ameliorative practices for restoring and maintaining impact of whole-tree harvesting on second-rotation growth of Sitka spruce: the first 10 years. Forest Ecology Manage. 1994;66(1):39–54. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(94)90147-3.

Egnell G. Is the productivity decline in Norway spruce following whole-tree harvesting in the final felling in boreal Sweden permanent or temporary? For Ecol Manage. 2011;261(1):148–53. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.045.

Smolander A, Saarsalmi A, Tamminen P. Response of soil nutrient content, organic matter characteristics and growth of pine and spruce seedlings to logging residues. For Ecol Manage. 2015;357:117–25. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.07.019.

Helmisaari H-S, Hanssen KH, Jacobson S, Kukkola M, Luiro J, Saarsalmi A, et al. Logging residue removal after thinning in Nordic boreal forests: long-term impact on tree growth. For Ecol Manage. 2011;261(11):1919–27. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2011.02.015.

Akselsson C, Westling O, Sverdrup H, Gundersen P. Nutrient and carbon budgets in forest soils as decision support in sustainable forest management. For Ecol Manage. 2007;238(1–3):167–74. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.10.015.

Pyttel PL, Köhn M, Bauhus J. Effects of different harvesting intensities on the macro nutrient pools in aged oak coppice forests. For Ecol Manage. 2015;349:94–105. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.03.037.

Johnson DW, West DC, Todd DE, Mann LK. Effects of sawlog vs. whole-tree harvesting on the nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and calcium budgets of an upland mixed oak forest. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1982;46(6):1304–9. doi:10.2136/sssaj1982.03615995004600060036x.

Johnson DW, Todd DE. Harvesting effects on long-term changes in nutrient pools of mixed oak forest. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1998;62(6):1725–35. doi:10.2136/sssaj1998.03615995006200060034x.

Aber JD. Why don’t we believe the models? Bull Ecol Soc Am. 1997;78(3):232–3.

Thiffault E, Paré D, Dagnault S, Morissette J. Guidelines—establishing permanent plots for monitoring the environmental effects of forest biomass harvesting. Quebec City, QC: Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Laurentian Forestry Centre; 2011.

Thiffault E, Paré D, Brais S, Titus BD. Intensive biomass removals and site productivity in Canada: a review of relevant issues. For Chron. 2010;86(1):36–42.

Lequy E, Conil S, Turpault M-P. Impacts of Aeolian dust deposition on European forest sustainability: a review. For Ecol Manage. 2012;267:240–52. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2011.12.005.

Binkley D, Högberg P. Does atmospheric deposition of nitrogen threaten Swedish forests? For Ecol Manage. 1997;92(1–3):119–52. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(96)03920-5.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jérôme Laganière for his helpful comments and Pamela Cheers for language editing. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the author.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Ecological Function

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Paré, D., Thiffault, E. Nutrient Budgets in Forests Under Increased Biomass Harvesting Scenarios. Curr Forestry Rep 2, 81–91 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-016-0030-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-016-0030-3