Abstract

Peers’ substance use is one of the most robust predictors of adolescent’s substance use. Albeit some empirical studies have explored factors that moderate peers’ influences on individual’s substance use, there is a lack of literature synthesis analyzing all existing research on the topic regardless the design and the type of substance. Because of that, the present systematic scoping review sought to explore the available studies that analyze moderators in the relation between peers’ and adolescent’s substance use. This review focused on studies including samples aged 10–19. The search was conducted in different databases and 43 studies meeting the criteria were finally included. It was found that elements such as emotional control, closeness to parents, school disapproval of substance use, friendship reciprocity or sport participation attenuated the impact of peers’ substance use on target’s substance use. On the other hand, avoidant and anxious attachment, sibling’s willingness to use substances, school troubles, peer support or setting criminogenic increased the likelihood of using substances among adolescents with peers who use substances. Results revealed that the effect of peers’ substance use on adolescent’s substance use is moderated by individual, family, school, peers and community factors. The effect of moderators could be different depending on the type of substance and the stage of adolescence. Substance use prevention programs for adolescents should be ecological, specific and adapted to the stage of adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Substance use is a primary social and health concern (Gray & Squeglia, 2018), whose initiation usually occurs in adolescence and tends to increase during this period (Zych et al., 2020). The harmful consequences of substance use in adolescence are well documented, including: poor school adjustment (Carbonneau et al., 2018), decrease in mental health (Brownlie et al., 2019) or problematic consumption later in life (Shanahan et al., 2021). The identification of risk and protective factors against substance use during adolescence is imperative to foster prevention and intervention. Relationships with peers who use substances is known to be one of the stronger risk factors for adolescent substance use. A recent meta-analysis found that peer connectedness was a strong predictor of adolescent substance use (Cole et al., 2024). Determining factors that moderate the impact of peers’ substance use on target’s substance use would be helpful to protect adolescents against substance consumption. Although some empirical studies have approached this issue, systematic reviews have not been conducted analyzing a wide range of substances and including all possible moderators. The objective of this study was to carry out a systematic scoping review about factors that moderate the association between peers’ and adolescent’s substance use.

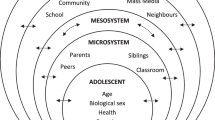

One of the most fruitful theories explaining adolescents’ behavior and development is the Ecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). This theory locates the individual—agent—in the center of the model and establishes a hierarchical number of systems that impact the individual more directly or indirectly. From this theoretical approach, risk and protective factors against substance use can belong to different domains: individual (e.g. social and emotional competences; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2021) or contextual, from micro (e.g. family; Trucco, 2020) to macro influences (e.g. pandemic-related factors; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2022). During adolescence, the peer group acquire a determining importance for youth and exerts a critical influence on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors (Steinberg & Silverberg, 1986). Peer group is defined as a set of people who interact on a level of equality and usually share elements like age or socio-economic position (American Psychological Association, 2015) Relationships with peers at early stages bring many benefits, such as the promotion of empathy, cooperation or conflict management strategies (Hartup, 1989). However, this system can also be a breeding ground for undesirable behaviors among adolescents (Sijtsema & Lindenberg, 2018). A robust body of research has demonstrated that peers’ substance use is a strong predictor of individual substance use for adolescents (Henneberger et al., 2021; Torrejón-Guirado et al., 2023). Identifying factors that protect adolescent against using substances when their peers do becomes imperative.

Adolescence should not be analyzed as a static element, but as a mutable period of life which is constantly changing. Peer effects on risky decision were found to be greater at early and middle adolescence in comparison with subsequent periods (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005). Empirical evidence also demonstrates that the ability to resist to peer influences significantly grow in the period 14–18 (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Because of this, peer influences on substance use should bear in mind possible fluctuations during adolescence. For example, it was showed that adolescents sharply increased their perception of peers’ tobacco use during the transition from middle to high school (Duan et al., 2009). This study found that peers’ tobacco use in middle school had an effect on target’s tobacco use both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. However, peers’ alcohol use influenced individual’s alcohol use cross-sectionally in middle school, but this effect disappeared longitudinally in the transition to high school. A narrative review about psychosocial factors linked to adolescent substance use brought to light that peer influences in substance during adolescence follow curvilinear progression: susceptibility to peer influences increases from adolescence onset, reaching the peak by age 14–15, and then start to decline (Trucco, 2020). The author concludes that this declining is due to the maturation of specific brain areas that makes adolescents less susceptible to peer influences. A systematic review concluded that the age of susceptibility to peer influences can be affected by other factors (Leung et al., 2011). For instance, individuals whose parents use substances are more likely to use substances when their peers use at early adolescence. These authors concluded that there is lack of evidence regarding elements that moderate substance use in adolescence when peers use.

Theoretical Approaches Explaining Influences on Adolescent Substance Use

Although the present review is strongly founded on the Ecological Model, there are many theoretical approaches that explain how several factors can interact with peer influences to increase or decrease the risk of substance use. The Resilience Theory seeks to identify elements that promote healthy development in individuals who develop in risky environments (Zimmerman, 2013). Within this theory, the protective factor model posits that individual and/or contextual factors can modify the effect of a risk factor. Empirical findings from a sample of children of alcoholics demonstrated that high scores in resilience at early adolescence delay drinking onset and decrease the likelihood of using substances later in life (Weiland et al., 2012).

The Social Capital Theory (Putnam, 2000) has been also the theoretical basis in research analyzing protective factors against adolescent substance use. Social capital is a set of features of the social structure, such as civic involvement and links among individuals, that lead to a perception of social trust, cohesion and support. A systematic review came to the conclusion that social capital is a key element in the prevention of alcohol use (Bryden et al., 2013). A study conducted in Sweden found that adolescents reporting the perception of living in a neighborhood with low social capital were at high risk of using alcohol, tobacco and illicit substances (Åslund & Nilsson, 2013). Family social capital elements have a considerable higher weight as protective factors against adolescent substance use, in comparison to school and community social capital (Wen, 2017).

The Social Control Theory (Hirschi, 1969) states that social bonds (attachment, commitment, involvement and belief) protect adolescents from engaging in antisocial behaviors, like substance use. Attachment is the strength of the link with other people within the social setting. Strong attachment to parents and teachers was identified as a protective factor against alcohol and tobacco use at early adolescence (Han et al., 2016). Commitment refers to the efforts dedicated by the individual to comply with social expectations. For example, substance use is less prevalent among students with better school performance (Bugbee et al., 2019). Involvement in socially valued activities decreases the risk of engaging in deviant activities such as substance use (McCabe et al., 2016). A strong belief in social norms makes less probable breaking these norms. It was also found that negative beliefs towards substance use significantly decrease the likelihood of using substances by adolescents (Hansen & Hansen, 2016).

Influences on adolescent substance use can be also explained by structural environmental elements that might imply a risk for using substances. The Broken Windows Theory (Wilson & Kelling, 1982) assumed that disorder in communities can drive to the perception that antisocial behavior would be unpunished. A meta-analysis of 152 studies on the topic showed that the perception of disorder in the neighborhood increases the odds of substance use and abuse (O’Brien et al., 2019). A comprehensive study combined self-reported data from a longitudinal cohort, together with a systematic social observation study and information from the US census. They found that adolescents were more prone to use substances when living in neighborhoods with more parks and playgrounds, and suggested that these spaces could be considered criminogenic (Kotlaja et al., 2018).

Existing Reviews About Moderators of the Association Between Peers’ and Adolescents’ Substance Use

A review of 40 studies about peer influences on adolescent smoking behavior analyzed the possible moderating effect of various parental practices, such as monitoring, support, or smoking at home. It found that positive parenting practices significantly weakened the impact of peers’ tobacco use on target’s smoking (Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010). These findings provide substantial evidence on the importance of family-related factors as moderators of peer influences. However, this study did not explore moderators other than parental elements and it was focused solely on smoking, ignoring other types of substances. A systematic review of factors moderating the link between peers’ and adolescents’ substance use showed that closest influences—individual characteristics or family, among others—exert a more powerful moderating impact compared to broader elements—e.g. community—(Marschall-Lévesque et al., 2014). This study considerably inspired the current review, given the broad perspective adopted, which included diverse substances, a wide range of moderators belonging to different dimensions and no restrictions regarding the study design. Despite its significant contribution to the topic, this review had two main limitations: tobacco use was not included and the search terms employed were scarce and not very accurate.

According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, the influence of peers’ smoking on own’s smoking behavior was strongest in collectivistic cultures in comparison with individualistic cultures; and when closeness to peers was higher (Liu et al., 2017). As closeness to peers is a significant element, the type of peer (friend, peer group, etc.) and the relationship should be taken into consideration when analyzing peer influences. Nonetheless, this study did not consider substances other than tobacco and the number of moderators analyzed was limited. A meta-analysis of 27 studies concluded that the effect of peer influence on individual substance use significantly differed depending on the type of substance and the measure of peers’ substance use—actual use or perceived use—(Watts et al., 2024). It highlights the importance of focusing on specific substances and differentiating between real substance use and the perception by the target. Notwithstanding, they only included studies with a longitudinal design, overlooking the relevant information that some cross-sectional studies can provide. Peer influences have been found to be more robust in short periods of time and it tends to weaken over time (Giletta et al., 2021). Moreover, socio-ecological moderators were not taken into consideration in this meta-analysis.

The Current Study

There is a substantial body of research demonstrating that peers’ substance use is one of the main predictors of adolescents’ substance use. Identifying factors that moderate this association is imperative in order to build evidence-based prevention strategies. Literature reviews on the topic conducted to date account for several limitations, such as focusing on specific substances, including a limited number of moderating variables or scarce terms in the search strategy. A holistic synthesis of existing literature considering a broad range of substances and socioecological moderators is still necessary to provide a comprehensive overview of the topic. The aim of the present study was to conduct a systematic scoping review to answer the following question: What moderates the association between peers’ and individual’s substance use in adolescence?

Methodology

This systematic scoping review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). This is a checklist consisting of 20 items (and 2 optional) to guide authors in the development of scoping reviews. A scoping instead of a classical systematic review was carried out given the considerable methodological diversity on research about this issue: many different substances (alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, etc.), inconsistent conceptualization of peers (best friend, group of friends, classmates, etc.), and a large variety of moderating factors (individual, family, school, etc.). In these cases, a scoping review emerges as the most suitable option to synthesize existing evidence (Colquhoun et al., 2014; Munn et al., 2018). The study protocol was not registered.

Search Strategy

Studies were searched on April 5th 2024 in three different databases: Web of Science (Core Collection, Current Contents Connects, Derwent Innovations Index, Grants Index, KCI-Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, SciELO Citation Index), SCOPUS and PROQUEST (APA PsycArticles®, APA PsycInfo®, Health & Medical Collection, Psychology Database).

The following search terms were used:

substance* OR drug* OR alcohol* OR drinking OR cannabi* OR marijuana OR hallucinogen* OR inhalant* OR opiate* OR opioid* OR heroin OR sedative* OR hypnotic* OR anxiolytic* OR stimulant* OR amphetamine* OR methamphetamine* OR ecstasy OR MDMA OR ketamine OR cocaine OR tobacco* OR cigarette* OR e-cigarette* OR vaper OR nicotine OR smoking.

AND

Peer* OR friend* OR partner*

AND

Moderate* OR buffer*

AND

Adolescent* OR child* OR schoolchild* OR student* OR teen*

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

This review conceptualized adolescence following the age range stipulated by the World Health Organization, that is, from 10 to 19 years (World Health Organization, 2021). Since this study built upon the Ecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), siblings were not considered as peers (because they also belong to the family system and these relationships might have differed elements with regular peers) and lab-based research was also excluded (because they omit ecological factors intrinsic to real life situations).

The inclusion criteria were: empirical studies, published in peer-reviewed journals, sample age range from 10 to 19 years, inclusion of a specific measurement of peers’ substance use, inclusion of a specific measurement of target’s substance use, include a moderator in the relation between peers’ and target’s substance use, participants must be humans, written in English or Spanish.

The exclusion criteria were: the peer is a sibling, lab-based research, substance use is combined with other elements into a single variable. No restrictions were set regarding the year of publication or sample size.

Screening Procedure

After searching manuscripts in databases, 8759 studies were found (WOS = 3511, SCOPUS = 2157, PROQUEST = 3091) and, after removing duplicates, 6838 were screened by title, abstract and keywords. The initial screening was conducted independently by both authors, excluding 6709 documents that did not meet the inclusion criteria, and selecting 129 to be full text analyzed. The two authors also screened the full texts. Discrepancies between reviewers were solved through dialogue and an external researcher specialized on peer influences was established to be consulted in case of disagreement. Out of these 129, 47 studies were excluded because sample’s age range was out of the scope of the review, in 16 substance use was not specifically measured, 16 did not include a moderator between peers’ and target’s substance use, 4 were not written in English or Spanish, 1 was not an empirical study, 1 was duplicated and 1 was lab-based research.

When participants’ age range was not included in the manuscript, authors were contacted in order to request this information. Finally, as can be seen in Fig. 1 (PRISMA flow diagram; Page et al., 2021), 43 studies were included to be analyzed in the current review.

Analytic Strategy

The following information was extracted from the manuscripts to be analyzed: year of publication, country, age, gender, design, ethnic-cultural group, sample size, who reported peers’ substance use, type of peer, the type of substance, the moderating variable and main findings of the study. Moreover, a quality assessment of included studies was performed. All these elements are shown in Table 1.

According to the classification provided by the World Health Organization (2023), adolescence was divided into two stages: early adolescence (from 10 to 14 years) and late adolescence (from 15 to 19 years). Study designs were labelled as cross-sectional or longitudinal. Following Murray et al. (2009), sample sizes over 400 were considered appropriate, while below 400 were identified as insufficient.

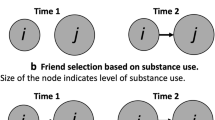

The report of peer substance use could be either perceived by the target or peer reported. The conceptualization of “peer” varied across studies, so it was coded into five categories for the current review: friends, best/close friends, peers or friends and peers. Due to the high diversity within some categories, it will be further explained in the results section.

Both peers’ and target’s substance use could be: alcohol use, tobacco use, cannabis use or composite. The variable was flagged as composite when different substances were included into a single variable. Moderating factors were categorized as follow: individual factors, family factors, school-related factors, peer-related factors and community factors.

Finally, the quality assessment of studies was carried out using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (National Heart, Lung & Blood Institute, 2021). This is an instrument that assesses the quality of the studies based on 14 items that analyze the statement of the objectives, sample characteristics and selection, data analyses, design, quality of the measurements and the execution of the research. Based on this evaluation, scores between 0 and 4 are poor, between 5 and 9 fair, between 10 and 14 good. The full evaluation can be seen in Table 2.

Results

Year and Country of Publication

Findings related to the year of publication of studies are represented in Table 3. Manuscripts meeting the criteria have been published every year since 2003, with the exceptions of 2008 and 2020. The number of publications peaks in 2004, 2014, 2017 and 2018, with four published works each. The tendency is decreasing, with only one publication on the topic yearly since 2018 to the present. There is also a considerable imbalance regarding the country where the studies were conducted, given that 26 out of 43 (which signifies more than 60%) were developed in the United States. Netherlands and Canada were the second most prevalent with four studies (9.3%) carried out in each country. The rest of studies analyzed samples from Spain (N = 3), Australia (N = 2), the United Kingdom (N = 2), South Africa (N = 1), Iceland (N = 1) and Italy (N = 1).

Stage of Adolescence, Study Design and Ethnicity

More than half of the studies (N = 22) explored samples including both early and late adolescents. Six investigations only included late adolescents and 15 studied early adolescents. Nonetheless, 5 out of these 15 were longitudinal and the sample changed from early to late adolescents at some point during the follow-up (Beier, 2017; Chaput-Langlois et al., 2022; Engels et al., 2004; Epstein et al., 2007a, 2007b; Epstein et al., 2007a, 2007b). On the whole, the majority of designs were longitudinal (58.1%). Within these 25 longitudinal studies, 10 had 2 waves of data collection, 8 had 3 waves, and 3 included 5 waves. The 3 remaining studies assessed participants 4, 6, and 7 times. Regarding ethnicity, 22 studies did not report specific information about ethnic-cultural groups within their samples. There was a diverse sample with no overrepresentation of specific groups in 11 samples. White/Caucasian adolescents were the main target in 7 studies. Among the 3 remaining studies, 1 was mainly focused on American Indian/Alaskan Natives, 1 in African Americans and 1 in European Americans.

Sample Size and Report of Peers’ Substance Use

Most of the samples (N = 34) had an appropriate number of participants (> 400), according to the Cambridge Quality Checklist (Murray et al., 2009), whereas just 9 documents analyzed fewer than 400 participants and were, therefore, considered insufficient. It should be noted that, of these 9 insufficient sample sizes, 8 corresponded to longitudinal investigations, which hinders the follow-up of large samples. Less than a third of the studies (N = 13) included a measurement of peer substance use reported by the peer itself through sociometric techniques and the rest (N = 30) measured peer substance use as perceived use by the target.

Specific Substances

In relation to specific substances (see Table 3), alcohol is the most studied, given that 27 (62.8%) studies explored target’s alcohol use and 24 (55.8%) peers’ alcohol use. After alcohol, a composite measurement is the second most common category for analyzing substance use among included studies (N = 8 for targets and N = 12 for peers). The target’s tobacco use is studied in 10 (23.3%) documents and peers’ tobacco use in 7 (16.3%). Likewise, 9 (20.9%) studies addressed the target’s cannabis use and 6 (14%) peers’ cannabis use.

Conceptualization of Peer

The conceptualization of “peer” was varied among studies. Articles were sorted into four main categories depending on their conceptualization of peers: friends (41.9%, N = 18), best/close friends (37.2%, N = 16), peers (14%, N = 6), friends and peers (7%, N = 3). Most of the studies included in the “friends” category literally asked the target about “friends”, but others employed similar terms such as “kids you hang out with” (Beckmeyer & Weybright, 2015).

The “peers” category was also diverse, as only one study included the term “peers” in the question to the target (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2018) and the other authors used a general definition of the construct “peers” in the questionnaire: “out of 100 teens your age” (Beckmeyer & Weybright, 2015), “people your age” (Epstein et al., 2007a, 2007b), “typical same-sex peer from student’s dorm floor” (LaBrie & Cail, 2011) or “general college students” (Wood et al., 2004).

Also, “best friend” and “close friend” are employed as interchangeable terms in literature. However, Hoeben et al. (2021) differentiated between best friends, on the one hand, and close friends, on the other hand, without providing a definition of each one. It should be highlighted that there is a diversity in the number of best/close friends addressed among studies, ranging from 1 (e.g. Poelen et al., 2007) to 5 (e.g. Larsen et al., 2010).

Main Findings

There was a wide range of moderators across studies. Classification of factors moderating peer influences are diverse in the existing literature. For instance, Prinstein (2007) sorted moderators in characteristics of adolescents, friends’ popularity and friendship quality. Dishion and Tipsord (2011) considered three types of moderators, including target characteristics, contextual characteristics and peer characteristics. In the present review, in line with Marschall-Lévesque et al., (2014), moderators were classified in the following categories: individual, family, school, peers and community. The full list of moderators sorted by category can be seen in Fig. 2. Individual moderators were analyzed in 26 studies (60.5%). The following variables weakened the relation between peers’ and own’s substance use: moral rules against alcohol use across different adolescent ages (Beier et al., 2017), sense of coherence at age 15–18 (García-Moya et al., 2013), good decision making among early adolescents (Botvin et al., 1998), emotional control at age 15–16 (García-Moya et al., 2017), positive social expectations about alcohol use (Hoeben et al., 2021), gender (being male) and fantasizing while listening to music at age 15 (Miranda et al., 2012). On the other hand, avoidant and anxiety attachment at age 15 increased the likelihood of alcohol and cannabis use, respectively, when peers consume at age 16 (Chaput-Langlois et al., 2022). Risk taking tendency at early adolescence made polysubstance use more probable among adolescents whose peers report substance use (Epstein et al., 2007a, 2007b). Conduct problems in a sample of 11–18 years old participants (Glaser et al., 2010) and social comparison orientation from age 13 to 16 (Litt et al., 2015) strengthened the impact of peers’ substance use on target’s alcohol use. Regarding personality traits, only sensation seeking moderated – increased—the association at age 13 (Pocuca et al., 2018). Both agentic and communal goals increased the impact at late adolescence, but communal goals decreased it at early adolescence (Meisel & Colder, 2015). Moreover, refusal skills did not moderate across different adolescent ages in the case of alcohol (Epstein et al., 2007a, 2007b; Weybright et al., 2019), tobacco and cannabis use (Glaser et al., 2010) but this variable significantly decreased the influence of peers on own’s polysubstance use (Epstein et al., 2007a, 2007b).

Family-related moderators were included in 12 manuscripts (27.9%). Closeness to parents and perception of being caught by parents lessened the impact of peers substance use on target’s marijuana use in a sample of 12–19 years old participants (Dorius et al., 2004). Frequency of contact with mother (but not father) also attenuated the association between peers’ and adolescent’s alcohol use among first year college students (LaBrie & Cail, 2011). On the contrary, this association was reinforced by consistent parental discipline from age 11 to 17 (Hoeben et al., 2021) and sibling’s behavioral willingness to use substances among early adolescents (Pomery et al., 2005). There were discrepancies in relation to the moderating effect of parental monitoring/knowledge, given that one study found a positive moderation between ages 11 and 17 (Hoeben et al., 2021), other studies reported a negative moderation among early adolescents (Bo et al., 2023; Kiesner et al., 2010) and others did not find a significant moderating effect when the sample included late adolescents up to 19 years (Dorius et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2004). Something similar happened with parental disapproval of substance use: some studies showed that this factor prevented from using substances when peers do across all adolescence stages below 19 (Chan et al., 2017; Martino et al., 2009), but the moderating effect was not significant at ages 18–19 (Wood et al., 2004). Only 6 (14%) studies explored school-related moderators. Disapproval of substance use at school and school racial diversity lessened the link between peers’ and individual substance use at age 12–17 (Su & Supple, 2016), whereas troubles at school bolstered this link among late adolescents (De la Haye et al., 2013). School bonding/attachment significantly attenuated the association in the case of alcohol use at early adolescence (Dickens et al., 2012), but not cannabis use at late adolescence (De la Haye et al., 2013).

Peer-related moderators were also examined in 6 (14%) studies. Elevated levels of descriptive norms about alcohol use weakened the link between best friends’ and target’s alcohol use (Hoeben et al., 2021). On the other hand, the association between peers’ and individual’s alcohol use was strengthened by high friendship reciprocity and sociometric status difference among early adolescents (Bot et al., 2005), and elevated peer support from early to late adolescence (Urberg et al., 2005). High close friend intimacy also increased the susceptibility to peers’ substance use in individuals around 14 years (Shadur & Hussong, 2014). Space time budget data showed that peers presence enhanced the risk of drink alcohol when peers drink at different adolescent stages (Beier et al., 2015). Friendship quality also strengthened peers influences on tobacco and cannabis use, but no alcohol across several adolescent ages (Mason et al., 2017; Poelen et al., 2007). Moreover, only three community-related factors were analyzed as moderators in 3 (7%) different studies. Formal (but not informal) sport participation decreased the likelihood of drinking alcohol when peers drink at age 13–16 (Halldorsson et al., 2014). Community-level adult daily smoking prevalence (age 13–17; Thrul et al., 2014), as well as setting criminogeneity (age 12–18; Beier, 2017) made stronger the association between peers’ and adolescent substance use.

Discussion

Peer’s substance use is known to be one of the biggest risk factors for adolescent substance use (Giletta et al., 2021). A deep understanding of factors that moderate the link between peer’s and individual’s substance use during adolescence is necessary in order to build prevention and intervention strategies. Existing literature reviews on the topic are exclusively focused on tobacco use (Liu et al., 2017; Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010), only analyze longitudinal research (Watts et al., 2024) or include too few terms in the search strategy (Marschall-Lévesque et al., 2014). The present systematic scoping review aimed at mapping all available studies that analyze moderators between peers’ and target’s substance use during adolescence regardless their design and including a wide variety of substances.

Methodological Discussion

The year of the publication of articles on the topic was analyzed. It has been an issue of interest for researchers since 2003, with 43 documents published to date. The number of publications has notably decreased since 2018, which can be suggesting a loss of scientific interest in this topic. Results in this field of research can be highly influenced by cultural aspects, considering that the vast majority of research is located in the United States. The latest evidence shows that the highest prevalence of substance use is reported by adolescents from Seychelles, Colombia and Montserrat (Farnia et al., 2024). The absence of research in these countries about factors moderating the influence of peers’ substance use, debilitate the development of prevention programs. Something similar specifically happens in Europe, where adolescent substance use is more prevalent in eastern countries (ESPAD Group, 2020), but this review did not find any research in those territories.

Another important point in this topic is the report of peers’ substance use, that can be perceived by the target or informed by the peers themselves through sociometric methods. Previous research showed that peers’ substance use tends to be overestimated, which makes controversial the validity of this measurement when is perceived by the target (Cox et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2006). On the other hand, sociometric techniques offer a more objective measurement of peers’ substance use. However, these data can be highly biased because they are often limited to peers’ relationships within school settings. Adolescents tend to establish social relationships with different groups inside and outside school. The restriction of analyses to in-school networks prevents from having a holistic and ecological understanding of peer influences on adolescent substance use. It would be useful if future studies explore whether these influences differed or not depending on the affiliation (inside or outside school) of peers, in order to respond to this research concern.

The type of specific substance approached in each study should be also mentioned. A total of 8 and 12 studies included in this review analyze target’s substance use and peers’ substance use, respectively, as a composite variable. In these cases, results should be interpreted with caution because different substances have diverse motivations to be used and their consequences differ too. Despite substance use is sometimes addressed as a general behavior, specificities of each substance should be taken into account. These findings also remark the lack of evidence about moderators of peers’ influences on e-cigarettes use. In the last few years, this new way of smoking is considerably increasing, to the point that its prevalence is even higher than conventional smoking nowadays (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2023) and its negative consequences have been proved in individuals who have never used tobacco (Alzahrani, 2023).

Individual Moderators

When gender was analyzed as moderator, peers’ substance use had a higher impact among boys (Kiesner et al., 2010; Leatherdale et al., 2006). Scientific literature systematically found that males tend to be more susceptible to peer influences in relation to risky behavior (McCoy et al., 2019). Not only peer influences but also gender differences in patterns of substance use need to be discussed. Historically, substance use has been more prone in male adolescents, as it was considered a masculine behavior and could be socially punished for girls (Cosma et al., 2022). However, recent findings show that the trend is changing and, in some cases, substance use is more prevalent among girls (Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2023a), which might be explained by gradual decrease of gender roles (Seedat et al., 2009). Updated studies should be conducted in order to check if patterns of substance use are also changing in terms of gender taking into account peer influences. Self-control did not moderate the effect of best friends’ consumption on alcohol use (Larsen et al., 2010). Self-control is considered one of the most powerful protective factors against substance use (Ford & Blumenstein, 2013; Grindal et al., 2019; Yun et al., 2016). The result found by Larsen et al. (2010) can be explained because they measured self-control with a short version of the original scale. Future studies could administrate full and accurate measurements of self-control to further explore its possible moderating effect.

Something similar happens with personality. Pocuca et al. (2018) showed that sensation seeking strengthened the impact of peers’ alcohol use, albeit they only measured risky personality profiles. Yet, Poelen et al. (2007) approached personality from the Big Five Model, which is the most accepted one to conceptualize personality, but none of the personality profiles was a significant moderator. Again, they measured the variable using a short version of the original instrument, which cannot be valid enough for such a complex construct. Chaput-Langlois et al. (2022) discovered that avoidant and anxious attachment increased the impact of peers’ alcohol and cannabis use, respectively, albeit they did not analyze other attachment styles. Secure attachment might be a protective factor against substance use when peers consume. Future research should consider all possible attachment styles.

Family-Related Moderators

Closeness to parents and the perception of being caught using substances lessened the impact of peers (Dorius et al., 2004). This highlights the importance of stablishing affective bonds and supervise the use of substance by the offspring. Parental support decreased the effect of peers on regular alcohol use (Bo et al., 2023), but not cannabis smoking (De la Haye et al., 2013; Dorius et al., 2004). This finding supports the notion that moderators might act differently depending on the type of substance. The role of siblings should be also pointed out, as their willingness to use substances significantly increased the influence of peers on target’s substance use. Future research must deeply explore whether siblings impact on adolescents’ substance use.

Discrepancies have been found about the moderating role of parental disapproval: when measuring disapproval of substance use in general, the moderation was significant (Chan et al., 2017; Martino et al., 2009); whereas measuring only disapproval of alcohol use does not show a moderation effect (Wood et al., 2004). It can be suggesting that parents should disapprove the use of all substances, rather than specific ones. There are also discrepancies among reviewed studies regarding the moderating effect of parental monitoring/knowledge in the relation between peers’ and individual’s substance use. All these studies measured the variable as single construct, despite Stattin and Kerr (2000) showed that it is composed by two dimensions: parental monitoring itself and child disclosure. Prior work has demonstrated that child disclosure is a consistent predictor of adolescent substance use, while parental monitoring itself is not (Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2023b).

School-Related Moderators

The role of school-related factors as moderators of the impact of peers’ substance use on individual’s substance use must be pointed out, given the determinant influence of school on adolescent development (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019). Only two school-elements were identified as protective factors against substance use when peers consume: school-level disapproval of substance use and school racial composition. Similarly to family disapproval, school disapproval of the consumption of diverse substances has a moderating effect (Su & Supple, 2016). It can be concluded that disapproval of substance use by near systems protects adolescents against substance use even when their peers do. Nevertheless, Su and Supple (2016) calculated school-level disapproval as the mean in substance use disapproval reported by each student in the corresponding school. Future studies could also collect information from teachers and other staff in order to have a richer measurement of the construct.

Su and Supple (2016) also found that racial diversity at school weakened the association between peers’ and adolescent’s substance use and they suggest that diversity can foster school connectedness. Yet, ethnic diversity at school have been identified as an element that decreases sense of vulnerability (Juvonen et al., (2018). Ethnic-cultural diversity can enrich school setting and provide safe context for students that prevents from undesirable behaviors. In the same way as parental support, school attachment/bonding moderated peers influences on alcohol (Dickens et al., 2012), but not cannabis use (De la Haye et al., 2013), which indicates that moderators work differently depending on the substance. School information about alcohol use was not a significant moderator (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2018). A systematic review pointed out that effective prevention programs must be focused on developing specific skills against substance use (Griffin & Botvin, 2010). Just information about the effects of substance use could not be enough to lessen the impact of peers.

Peers and Community-Related Moderators

Friendship reciprocity increased the odds of using alcohol when peers drinking (Bot et al., 2005). It can be due to the tendency of adolescents to select friends with similar interests. So, the creation of class groups at school taking into account diversity of interests among students could be an effective strategy to prevent substance use. Bot et al. (2005) also showed that there is a significant effect of sociometric status difference, in a way that participants with lower sociometric status were more prone to be influenced by the substance use of high-status friends. A plausible explanation could be that students with fewer friends are afraid of being alone. If these students are friends of adolescents with elevated number of friends, they can assume the maintenance of friendship as a competition and they can adopt behaviors from high-status friends in order to satisfy them. Higher friendship quality strengthened the link between peers’ and target’s tobacco and cannabis use, but not alcohol drinking (Mason et al., 2017; Poelen et al., 2007). Alcohol drinking is a socially accepted behavior that can be done with different people, regardless the relationship with them. However, tobacco and, especially, cannabis use are less common and their use can be exclusive of some settings which require certain level on confidence.

Only three studies explored macro-elements, labelled as community-related factors in this review. A study conducted by Beier (2017) employing space–time budget data showed setting criminogeneity made adolescents more vulnerable to alcohol drinking when their friends group drinks. This highlights the importance of offering healthy leisure activities to adolescents in order to avoid substance in unstructured contexts. Formal—but not informal—sport enrollment was found to lessen the influence of friends’ alcohol use on own’s alcohol use (Halldorson et al. 2014). Formal sports require some commitment, that can prevent from substance use. The link between peers’ and target’s tobacco smoking was stronger in communities with higher rates of adult daily smoking (Thrul et al., 2014). The transmission of problematic behaviors, such as substance use, among generations has been already reported (Neppl et al., 2020). Preventive strategies need to be stronger in communities with high levels of consumption among adults in order to avoid or mitigate the impact in the next generation.

Developmental Considerations

Some of the results found in this review need to be analyzed from a developmental perspective, given that the effect of specific moderators can differ depending on age. Self-control was not a significant moderator. The two included studies exploring the effect of self-control (Botvin et al., 1998; Larsen et al.; 2010) measured the variable before age 15. It is well known that from late adolescence occurs a neurological maturation that entails a considerable development of self-regulation strategies (Shulman et al., 2016). Self-control might be further developed by late adolescents and it can protect against peer influences when the above mentioned maturation takes place. More research is needed to confirm this. Also, parental support lessened the impact of peers’ alcohol use at early adolescence (Bo et al., 2023). The moderating effect of parental support was not significant in late adolescence (De la Haye et al., 2013; Dorius et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2004). Scientific evidence demonstrate that family is the context of reference during childhood, but its influence on individuals tend to decrease during adolescence (Kerr et al., 2010). Parental elements, such as parental support, can remain as protectors for early adolescents, but the effect could disappear as family loses weight at late adolescence. Future studies should explore whether family influences interact with peers depending on age.

Something similar happens with school bonding/attachment. This element moderated peer influences on substance use at early (Dickens et al., 2012) but not at late adolescence (De la Haye et al., 2013). Just like family, the protective role of the emotional link with school can be significant for early adolescents, but it might decrease as students grow. Another important element to consider is school information about substance use. Rodríguez-Sánchez et al. (2018) showed that school information did not moderate the impact of peers’ substance use at age 14–16. Nevertheless, school information did weaken the association between parental alcohol use and target’s alcohol use. Susceptibility to peer influences reaches the peak at this age, at the same time that parental influences decrease. Therefore, school information about alcohol use could be useful to lessen peer influences at early adolescence, when susceptibility is lower. School-based prevention programs must consider that the success or failure of some elements in decreasing or preventing substance use can depend on the age of application.

Limitations

The current review account for some limitations that should be acknowledged. Although studies were searched and screened independently by two researchers, any eligible study could be missed during that process. Not only peers’ behaviors but also attitudes towards substance use can influence adolescents’ substance use. However, these elements were out of scope of the present review.

Implications and Future Directions

The current review has important implications for research and practice. Regarding research implications, it seems that there is not a corpus of research itself about factors moderating the association between peers’ and adolescent’s substance use, but a set of independent studies somehow disconnected among them. Future investigations should bear in mind the following recommendations to cover the detected gaps. First, new studies should be conducted to explore social changes related to substance use (e.g. new substances like e-cigarettes or changing trends between genders). Second, more replication is needed, as the vast majority of moderators have been explored only in one study. Third, moderators should be measured attending all dimensions from the most accepted theories (e.g. personality or attachment) and full questionnaires (avoiding short versions) to collect as much information as possible. From an ecological perspective, there is a dearth of evidence about moderators belonging to the mesosystem. This is, it would be worthy to identify how the interaction between different systems (e.g. relationships family-school) can mitigate peer influences. In relation to implications for practice, fostering the elements identified as moderators in the present review can be useful to prevent substance use. At the individual level, the promotion of moral rules against substance use, sense of coherence and decision-making are key protective factors even when peers consume. The inclusion of these dimensions in school prevention programs can be fruitful, given that only information at school about the risk of substance use did not moderate peer influences. Both school and families must disapprove the use of any substance, as disapproval attenuated the impact by peers.

Conclusion

Previous reviews investigating factors that moderate the relation between peers’ and adolescent’s substance use typically focused on a single substance, limited their scope to specific moderators or only included longitudinal research. The present review provides a comprehensive and holistic synthesis of moderators of the association between peers’ and adolescent’s substance use, including a wide range of substances, integrating moderators belonging to different domains, and analyzing both cross-sectional and longitudinal information. Findings showed that several individual and contextual factors interact with peers’ substance use to increase or decrease the risk of target’s substance use. Successful strategies to prevent adolescent substance use should adopt an ecological approach by promoting individual skills, as well as working together with family, school, peers and community when possible in prevention programs. Prevention efforts need to follow a developmental perspective and be adapted to the targeted age group, as effective elements at a particular stage of adolescence could not be effective at another time point.

References

Note: asterisks indicate studies included in the systematic review

Alzahrani, T. (2023). Electronic cigarette use and myocardial infarction. Cureus, 15(11), e48402. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.48402

American Psychological Association (2015). APA Dictionary of Psychology (Second Edition). American Psychological Association.

Åslund, C., & Nilsson, K. W. (2013). Social capital in relation to alcohol consumption, smoking, and illicit drug use among adolescents: A cross-sectional study in Sweden. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-33

Beckmeyer, J. J., & Weybright, E. H. (2015). Perceptions of alcohol use by friends compared to peers: Associations with middle adolescents’ own use. Substance Abuse, 37(3), 435–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1134754

Beier, H. (2017). Situational peer effects on adolescents’ alcohol consumption: The moderating role of supervision, activity structure, and personal moral rules. Deviant Behavior, 39(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.1286173

Bo, A., Zhang, L., Lu, W., & Chen, D. G. (2023). Moderating effects of positive parenting on the perceived peer alcohol use and adolescent alcohol use relationship: Racial, ethnic, and gender differences. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 40(3), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00780-x

Bot, S. M., Engels, R. C. M. E., Knibbe, R. A., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2005). Friend’s drinking behaviour and adolescent alcohol consumption: The moderating role of friendship characteristics. Addictive Behaviors, 30(5), 929–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.012

Botvin, G. J., Malgady, R. G., Griffin, K. W., Scheier, L. M., & Epstein, J. A. (1998). Alcohol and marijuana use among rural youth: Interaction of social and intrapersonal influences. Addictive Behaviors, 23(3), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00006-9

*Bountress, K., Chassin, L., Presson, C. C., & Jackson, C. (2016). The effects of peer influences and implicit and explicit attitudes on smoking initiation in adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 62(4), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.62.4.0335

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Brownlie, E., Beitchman, J. H., Chaim, G., Wolfe, D. A., Rush, B., & Henderson, J. (2019). Early Adolescent substance use and mental health problems and service utilisation in a school-based sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 64(2), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718784935

Bryden, A., Roberts, B., Petticrew, M., & McKee, M. (2013). A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health & Place, 21, 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.01.012

Bugbee, B. A., Beck, K. H., Fryer, C. S., & Arria, A. M. (2019). Substance use, academic performance, and academic engagement among high school seniors. The Journal of School Health, 89(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12723

Carbonneau, R., Vitaro, F., & Tremblay, R. E. (2018). School adjustment and substance use in early adolescent boys: Association with paternal alcoholism with and without dad in the home. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(7), 1008–1035.

Chan, G. C. K., Kelly, A. B., Carroll, A., & Williams, J. W. (2017). Peer drug use and adolescent polysubstance use: Do parenting and school factors moderate this association? Addictive Behaviors, 64, 78–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.004

*Chaput-Langlois, S., Parent, S., Castellanos Ryan, N., Vitaro, F., & Séguin, J. R. (2022). Friends, attachment and substance use in adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 83(August). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2022.101457

Cole, V. T., Richmond-Rakerd, L. S., Bierce, L. F., Norotsky, R. L., Peiris, S. T., & Hussong, A. M. (2024). Peer connectedness and substance use in adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 38(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000914

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014) Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Cosma, A., Elgar, F. J., de Looze, M., Canale, N., Lenzi, M., Inchley, J., & Vieno, A. (2022). Structural gender inequality and gender differences in adolescent substance use: A multilevel study from 45 countries. SSM-Population Health, 19, 101208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101208

Cox, M. J., DiBello, A. M., Meisel, M. K., Ott, M. Q., Kenney, S. R., Clark, M. A., & Barnett, N. P. (2019). Do misperceptions of peer drinking influence personal drinking behavior? Results from a complete social network of first-year college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(3), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000455

De La Haye, K., Green, H. D., Kennedy, D. P., Pollard, M. S., & Tucker, J. S. (2013). Selection and influence mechanisms associated with marijuana initiation and use in adolescent friendship networks. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(3), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12018

*Dickens, D. D., Dieterich, S. E., Henry, K. L., & Beauvais, F. (2012). School bonding as a moderator of the effect of peer influences on alcohol use among American Indian adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(4), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2012.73.597

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412

Dorius, C. J., Bahr, S. J., Hoffmann, J. P., & Harmon, E. L. (2004). Parenting practices as moderators of the relationship between peers and adolescent marijuana use. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(1), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00011.x-i1

Duan, L., Chou, C. P., Andreeva, V. A., & Pentz, M. A. (2009). Trajectories of peer social influences as long-term predictors of drug use from early through late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(3), 454–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9310-y

Ellickson, P. L., Bird, C. E., Orlando, M., Klein, D., & McCaffrey, D. F. (2003). Social context and adolescent health behavior: Does school-level smoking prevalence affect students’ subsequent smoking behavior? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(4), 525–535.

Engels, R. C. M. E., Vitaro, F., Blokland, E. D. E., de Kemp, R., & Scholte, R. H. J. (2004). Influence and selection processes in friendships and adolescent smoking behaviour: The role of parental smoking. Journal of Adolescence, 27(5), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.006

Ennett, S. T., Faris, R. W., Hussong, A. M., Gottfredson, N., & Cole, V. (2018). Depressive symptomology as a moderator of friend selection and influence on substance use involvement: Estimates from grades 6 to 12 in six longitudinal school-based social networks. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(11), 2337–2352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0915-5

Epstein, J. A., Bang, H., & Botvin, G. J. (2007a). Which psychosocial factors moderate or directly affect substance use among inner-city adolescents? Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 700–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.011

Epstein, J. A., Zhou, X. K., Bang, H., & Botvin, G. J. (2007b). Do competence skills moderate the impact of social influences to drink and perceived social benefits of drinking on alcohol use among inner-city adolescents? Prevention Science, 8(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-006-0054-1

ESPAD Group. (2020). ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. EMCDDA Publications Office of the European Union.

Farnia, V., Ahmadi Jouybari, T., Salemi, S., Moradinazar, M., Khosravi Shadmani, F., Rahami, B., Alikhani, M., Bahadorinia, S., & Mohammadi Majd, T. (2024). The prevalence of alcohol consumption and its related factors in adolescents: Findings from Global School-based Student Health Survey. PLoS ONE, 19(4), e0297225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297225

Ford, J. A., & Blumenstein, L. (2013). Self-control and substance use among college students. Journal of Drug Issues, 43(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042612462216

García-Moya, I., Ortiz Barón, M. J., & Moreno, C. (2017). Emotional and psychosocial factors associated with drunkenness and the use of tobacco and cannabis in adolescence: Independent or interactive effects? Substance Use and Misuse, 52(8), 1039–1050. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1271431

*García-Moya, I., Jiménez-Iglesias, A., & Moreno, C. (2013). Sentido de coherencia y consumo de sustancias en adolescentes españoles. ¿Depende el efecto del SOC de los patrones de consumo de sustancias del grupo de iguales? Adicciones, 25(2), 109. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.58

Gardner, M., & Steinberg, L. (2005). Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Developmental Psychology, 41(4), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625

Giletta, M., Choukas-Bradley, S., Maes, M., Linthicum, K. P., Card, N. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2021). A meta-analysis of longitudinal peer influence effects in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 147(7), 719–747. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000329

Glaser, B., Shelton, K. H., & van den Bree, M. B. M. (2010). The moderating role of close friends in the relationship between conduct problems and adolescent substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.022

Gray, K. M., & Squeglia, L. M. (2018). Research review: What have we learned about adolescent substance use? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 59(6), 618–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12783

Griffin, K. W., & Botvin, G. J. (2010). Evidence-based interventions for preventing substance use disorders in adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(3), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.005

Grindal, M., Admire, A., & Nieri, T. (2019). A theoretical examination of immigrant status and substance use among Latino college students. Deviant Behavior, 40(11), 1372–1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2018.1512257

Halldorsson, V., Thorlindsson, T., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2014). Adolescent sport participation and alcohol use: The importance of sport organization and the wider social context. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 49(3–4), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690213507718

Han, Y., Kim, H., & Lee, D. (2016). Application of social control theory to examine parent, teacher, and close friend attachment and substance use initiation among Korean Youth. School Psychology International, 37(4), 340–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316641727

Hansen, W. B., & Hansen, J. L. (2016). Using attitudes, age and gender to estimate an adolescent’s substance use risk. Journal of Children’s Services, 11(3), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-06-2015-0020

Hartup, W. W. (1989). Social relationships and their developmental significance. American Psychologist, 44(2), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.120

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. (2021). Study quality assessment tools. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Henneberger, A. K., Mushonga, D. R., & Preston, A. M. (2021). Peer influence and adolescent substance use: A systematic review of dynamic social network research. Adolescent Research Review, 6(1), 57–73.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of deliquency. California University Press.

Hoeben, E. M., Rulison, K. L., Ragan, D. T., & Feinberg, M. E. (2021). Moderators of friend selection and influence in relation to adolescent alcohol use. Prevention Science, 22(5), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01208-9

Juvonen, J., Kogachi, K., & Graham, S. (2018). When and How do students benefit from ethnic diversity in middle school? Child Development, 89(4), 1268–1282. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12834

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Burk, W. J. (2010). A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 39–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00623.x

Kiesner, J., Poulin, F., & Dishion, T. J. (2010). Adolescent substance use with friends: Moderating and mediating effects of parental monitoring and peer activity contexts. Merrill Palmer Quarterly (Wayne State University Press), 56(4), 529–556. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2010.0002

Kotlaja, M. M., Wright, E. M., & Fagan, A. A. (2018). Neighborhood parks and playgrounds: Risky or protective contexts for youth substance use? Journal of Drug Issues, 48(4), 657–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042618788834

LaBrie, J. W., & Cail, J. (2011). Parental interaction with college students: The moderating effect of parental contact on the influence of perceived peer norms on drinking during the transition to college. Journal of College Student Development, 52(5), 610–621. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2011.0059

Larsen, H., Overbeek, G., Vermulst, A. A., Granic, I., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2010). Initiation and continuation of best friends and adolescents’ alcohol consumption: Do self-esteem and self-control function as moderators? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(5), 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025409350363

Leatherdale, S. T., Manske, S., & Kroeker, C. (2006). Sex differences in how older students influence younger student smoking behaviour. Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 1308–1318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.003

Leung, R. K., Toumbourou, J. W., & Hemphill, S. A. (2011). The effect of peer influence and selection processes on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Health Psychology Review, 8(4), 426–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2011.587961

Litt, D. M., Stock, M. L., & Gibbons, F. X. (2015). Adolescent alcohol use: Social comparison orientation moderates the impact of friend and sibling behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(3), 514–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12118

Liu, J., Zhao, S., Chen, X., Falk, E., & Albarracín, D. (2017). The influence of peer behavior as a function of social and cultural closeness: A meta-analysis of normative influence on adolescent smoking initiation and continuation. Psychological Bulletin, 143(10), 1082–1115. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000113

Marschall-Lévesque, S., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Vitaro, F., & Séguin, J. R. (2014). Moderators of the association between peer and target adolescent substance use. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 48–70.

Martens, M. P., Page, J. C., Mowry, E. S., Damann, K. M., Taylor, K. K., & Cimini, M. D. (2006). Differences between actual and perceived student norms: an examination of alcohol use, drug use, and sexual behavior. Journal of American College Health, 54(5), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.54.5.295-300

Martino, S. C., Ellickson, P. L., & McCaffrey, D. F. (2009). Multiple trajectories of peer and parental influence and their association with the development of adolescent heavy drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 34(8), 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.006

Mason, M. J., Zaharakis, N. M., Rusby, J. C., Westling, E., Light, J. M., Mennis, J., & Flay, B. R. (2017). A longitudinal study predicting adolescent tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use by behavioral characteristics of close friends. Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 31(6), 712–720. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000299

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review orscoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

McCabe, K. O., Modecki, K. L., & Barber, B. L. (2016). Participation in organized activities protects against adolescents’ risky substance use, even beyond development in conscientiousness. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(11), 2292–2306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0454-x

McCoy, S. S., Dimler, L. M., Samuels, D. V., & Natsuaki, M. N. (2019). Adolescent susceptibility to deviant peer pressure: Does gender matter? Adolescent Research Review, 4(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0071-2

Meisel, S. N., & Colder, C. R. (2015). Social goals and grade as moderators of social normative influences on adolescent alcohol use. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(12), 2455–2462. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12906

Ministerio de Sanidad. (2023). Encuesta sobre uso de drogas en enseñanzas secundarias en España (ESTUDES), 1994–2023. Gobierno de España, Ministerio de Sanidad.

Miranda, D., Gaudreau, P., Morizot, J., & Fallu, J. S. (2012). Can fantasizing while listening to music play a protective role against the influences of sensation seeking and peers on adolescents’ substance use? Substance Use and Misuse, 47(2), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.637460

Murray, J., Farrington, D. P., & Eisner, M. P. (2009). Drawing conclusions about causes from systematic reviews of risk factors: The Cambridge Quality Checklists. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 5, 1–23.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25388.

Neppl, T. K., Diggs, O. N., & Cleveland, M. J. (2020). The intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting, substance use, and emotional distress: Impact on the third-generation child. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 34(8), 852–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000551

O’Brien, D. T., Farrell, C., & Welsh, B. C. (2019). Broken (windows) theory: A meta-analysis of the evidence for the pathways from neighborhood disorder to resident health outcomes and behaviors. Social Science & Medicine, 228, 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.11.015

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372(7)1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pocuca, N., Hides, L., Quinn, C. A., White, M. J., Mewton, L., Newton, N. C., Slade, T., Chapman, C., Andrews, G., Teesson, M., Allsop, S., & McBride, N. (2018). The interactive effects of personality profiles and perceived peer drinking on early adolescent drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(2), 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000322

Poelen, E. A., Engels, R. C., Van Der Vorst, H., Scholte, R. H., & Vermulst, A. A. (2007). Best friends and alcohol consumption in adolescence: A within-family analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2–3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.008.

*Pollard, M. S., Tucker, J. S., Green, H. D., de la Haye, K., & Espelage, D. L. (2018). Adolescent peer networks and the moderating role of depressive symptoms on developmental trajectories of cannabis use. Addictive Behaviors, 76(July 2017), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.07.019

Pomery, E. A., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Cleveland, M. J., Brody, G. H., & Wills, T. A. (2005). Families and risk: Prospective analyses of familial and social influences on adolescent substance use. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.560

Prinstein M. J. (2007). Moderators of peer contagion: a longitudinal examination of depression socialization between adolescents and their best friends. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: the Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 36(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701274934

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: the collapse of America’s social capital. Simon and Shuster.

Rodríguez-Ruiz, J., Zych, I., Llorent, V., & Marín-López, I. (2021). A longitudinal study of preadolescent and adolescent substance use: Within-individual patterns and protective factors. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 21(3), 100251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100251

Rodríguez-Ruiz, J., Zych, I., & Llorent, V. J. (2022). Adolescent compliance with anti-COVID measures. is it related to substance use?. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00751-4

Rodríguez-Ruiz, J., Zych, I., Llorent, V. J., Marín-López, I., Espejo-Siles, R., & Nasaescu, E. (2023a). A longitudinal study of protective factors against substance use in early adolescence. An ecological approach. International Journal of Drug Policy, 112, 103946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103946

Rodríguez-Ruiz, J., Zych, I., Ribeaud, D., Steinhoff, A., Eisner, M., Quednow, B. B., & Shanahan, L. (2023b). The influence of different dimensions of the parent–child relationship in childhood as longitudinal predictors of substance use in late adolescence. The mediating role of self-control. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01036-8

Rodriguez-Sanchez, C., Sancho-Esper, F., & Casalò, L. V. (2018). Understanding adolescent binge drinking in Spain: How school information campaigns moderate the role of perceived parental and peer consumption. Health Education Research, 33(5), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyy024

Seedat, S., Scott, K. M., Angermeyer, M. C., Berglund, P., Bromet, E. J., Brugha, T. S., Demyttenaere, K., de Girolamo, G., Haro, J. M., Jin, R., Karam, E. G., Kovess-Masfety, V., Levinson, D., Medina Mora, M. E., Ono, Y., Ormel, J., Pennell, B. E., Posada-Villa, J., Sampson, N. A., Williams, D., Kessler, R. C. (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(7), 785–795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36

Segura, Y. L., Page, M. C., Neighbors, B. D., Nichols-Anderson, C., & Gillaspy, S. (2004). The Importance of peers in alcohol use among latino adolescents: The role of alcohol expectancies and acculturation. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 2(3), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1300/J233v02n03_02

Shadur, J. M., & Hussong, A. M. (2014). Friendship intimacy, close friend drug use, and self-medication in adolescence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(8), 997–1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407513516889

Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Copeland, W. E., Ribeaud, D., Eisner, M., & Quednow, B. B. (2021). Frequent teenage cannabis use: Prevalence across adolescence and associations with young adult psychopathology and functional well-being in an urban cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 228, 109063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109063

Shulman, E. P., Smith, A. R., Silva, K., Icenogle, G., Duell, N., Chein, J., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.010

Siennick, S. E., Widdowson, A. O., Woessner, M., & Feinberg, M. E. (2016). Internalizing symptoms, peer substance use, and substance use initiation. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 645–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12215

Sijtsema, J. J., & Lindenberg, S. M. (2018). Peer influence in the development of adolescent antisocial behavior: Advances from dynamic social network studies. Developmental Review, 50(Part B), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.08.002

Simons-Morton, B. G., & Farhat, T. (2010). Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(4), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00210

Steinberg, L., & Monahan, K. C. (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1531–1543. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531

Steinberg, L., & Silverberg, S. B. (1986). The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child Development, 57(4), 841–851. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130361

Su, J., & Supple, A. J. (2016). School substance use norms and racial composition moderate parental and peer influences on adolescent substance use. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(3–4), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12043

Thrul, J., Lipperman-kreda, S., Grube, J. W., & Friend, K. B. (2014). Community-level adult daily smoking prevalence moderates the association between adolescents’ cigarette smokin and perceived smoking by friends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(9), 1527–1535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0058-7

Torrejón-Guirado, M. C., Baena-Jiménez, M. Á., Lima-Serrano, M., de Vries, H., & Mercken, L. (2023). The influence of peer’s social networks on adolescent’s cannabis use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1306439. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1306439

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Tunçalp, Ö., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Trucco, E. M. (2020). A review of psychosocial factors linked to adolescent substance use. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 196, 172969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172969

Urberg, K., Goldstein, M. S., & Toro, P. A. (2005). Supportive relationships as a moderator of the effects of parent and peer drinking on adolescent drinking. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00084.x

Watts, L. L., Hamza, E. A., Bedewy, D. A., & Moustafa, A. A. (2024). A meta-analysis study on peer influence and adolescent substance use. Current Psychology, 43, 3866–3881.

Weiland, B. J., Nigg, J. T., Welsh, R. C., Yau, W. Y., Zubieta, J. K., Zucker, R. A., & Heitzeg, M. M. (2012). Resiliency in adolescents at high risk for substance abuse: Flexible adaptation via subthalamic nucleus and linkage to drinking and drug use in early adulthood. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(8), 1355–1364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01741.x

Wen, M. (2017). Social Capital and adolescent substance use: The role of family, school, and neighborhood contexts. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 27(2), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12299

Weybright, E. H., Beckmeyer, J. J., Caldwell, L. L., Wegner, L., & Smith, E. A. (2019). With a little help from my friends? A longitudinal look at the role of peers versus friends on adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Adolescence, 73, 14–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.03.007

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. (1982). Broken windows: The police and neighorhood safety. Atlantic, 127, 29–38.

Wood, M. D., Mitchell, R. E., Read, J. P., & Brand, N. H. (2004). Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19

World Health Organisation. (2021). Adolescent mental health [Fact Sheet]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

World Health Organization. (2023). Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation (Second Edition). World Health Organization

Yun, I., Kim, S.-G., & Kwon, S. (2016). Low self-control among South Korean adolescents: A test of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s generality hypothesis. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(10), 1185–1208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15574683

Zimmerman, M. A. (2013). Resiliency theory: A strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 40(4), 381–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113493782

Zych, I., Rodríguez-Ruiz, J., Marín-López, I., & Llorent, V. J. (2020). Longitudinal stability and change in adolescent substance use: A latent transition analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104933

Acknowledgements

This publication was funded by Universidad de Extremadura.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions