Abstract

Sustainable approaches in the agricultural sector are important to addressing problems relating to food security and nutrition around the globe. To obviate these problems, it has become crucial to administer methods of farming that are ecologically compatible, holistic and organic in nature. Dutch farmers are moving towards more sustainable and circular production methods to respond to the various challenges, including biodiversity loss and climate change, whilst maintaining a viable business model. To generate further insight into circular and nature-inclusive or nature-positive agricultural business models (CNABM), we describe a conceptual framework that could help farmers, their advisers and, possibly, funding organisations to identify critical success factors for the implementation of circular and nature-inclusive or nature-positive business models in a qualitative way. The framework was built on a synthesis of existing literature and seven empirical case studies drawing on in-depth interviews. Prior to the case studies, the framework was tested through a desk study focused on sugar-beet cultivation. Based on existing literature and the pilot case on sugar-beet cultivation, we found that three conditions are needed in order to identify these critical success factors. (1) It is important to consider the barriers and drivers in the social and physical contexts within which entrepreneurs involved in such business models operate (‘adoption factors’). (2) Sustainable business models should go beyond delivering economic value and include other forms of value for a broader range of stakeholders. Moreover, attention should be paid to strengths and weaknesses of the business model. (3) Traditional business models (e.g. the business model canvas, or BMC) should be extended to include sustainability-related elements (sustainability impact). The framework proved useful for identifying the business models, along with their vulnerabilities and potential opportunities. Although the framework is meant for use with circular and nature-inclusive or nature-positive agricultural business models, it can be applied to other sustainable agricultural business models as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past decade, the importance of sustainable food systems has been receiving increasing emphasis. Sustainable approaches in the agricultural sector are of the utmost importance to addressing problems relating to food security and nutrition around the globe. To obviate these problems, it has become crucial to administer methods of farming that are ecologically compatible, holistic and organic in nature [1]. For farmers, this entails being confronted with increasing pressures on land and concerns about the emission of greenhouse gasses, ammonia and minerals in relation to climate goals, as well as water quality and animal welfare in relation to human health [1, 2]. If current production systems continue as they are, pressure on the environment is expected to increase as the global population grows [3, 4].

In the Netherlands, a focus on increasing productivity and reducing costs has resulted in monocultures, which have a negative impact on the environment, especially in terms of biodiversity, water quality and the attractiveness of the landscape. According to the vision of the Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, “[T]he way in which we produce our food is shifting ever more out of balance. We are taking more than the planet can give, and this is not sustainable” [5, p. 5]. The Dutch government advocates a transition to circular agriculture, with nature-inclusive agriculture as one important perspective [6]. Nature-inclusive farming aims to promote more sustainable agricultural practices that will minimise negative ecological impacts and maximise positive ones, whilst generating benefits from natural processes [7]. At the international level, this aligns with the search for nature-positive business models, as advocated by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) [8], the World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2023 across a variety of sectors [9], and the European Business & Nature Summit in Milan in 2023 [10]. The initiatives have encouraged further business actions towards the development of nature-positive business models.

Such transitions involve complex processes, and they require radical changes in both social and technological systems [7, 11]. For Dutch farmers, the transition will require moving towards more sustainable production methods in response to challenges (e.g. biodiversity loss and climate change), whilst also maintaining a viable business model.

As demonstrated by the Netherlands national taskforce on earning capacity for circular agriculture, the development of new revenue/business models poses a number of major challenges. Stressing the urgent need for a suitable revenue model, this taskforce argues that such models are crucial to the success of the transition towards more sustainable agriculture [12]. Within the European context, the same argument has been applied to the development of business models for a circular and sustainable bioeconomy [13,14,15].

To help identify critical success factors for the successful implementation of circular and nature-inclusive or nature-positive agricultural business models (CNABM), we build on a framework developed by Antikainen and Valkokari [16] and adapted it according to a synthesis of literature. A preliminary examination of the framework was conducted through a desk study on sugar-beet cultivation, which resulted in minor adaptations to the framework. In a subsequent step, we qualitatively tested the framework based on seven empirical case studies. The aim of our study was to identify and test a framework for critical success factors for circular and nature-inclusive or nature-positive agricultural business models (CNABM) within the context of stakeholders preparing their farms for the transition to the future. In our study, CNABMs describe the ways in which farmers work and make money whilst also carefully handling natural resources, managing the soil in a sustainable manner and minimising emissions.

The section “Research methods” introduces the materials and methods which form the basis of this paper. The section “Results” then introduces the literature review which provides the foundation for our approach by the identification of key elements of CNABMs (Section “Literature Review on Business Model Strategies and Elements of Circular and Nature Inclusive Business Models”). This is followed by a brief analysis of a desk study concerning Dutch sugar beet cultivation (Section “Analysis of the Sugar Beet Case”) and a more detailed analysis of seven empirical case studies that illustrate the practical applications of our approach (Section “Analysis of Seven Empirical Case Studies”). The results concludes with the presentation of the framework for CNABMs (Section “Towards a Conceptual Framework for Analyzing CNABMs”). Finally, the discussion offers a discussion of the key findings, while the section “Conclusions” presents the conclusions. In this paper we will from here on refer to nature-inclusive agriculture when we mean nature-inclusive or nature-positive agriculture.

Research Methods

The study consisted of three parts (see Fig. 1):

-

1)

An exploratory literature review to find out whether circular or sustainable business models that have been developed primarily for industrial applications can be applied in circular and nature-inclusive agricultural business models (CNABMs), as well as to identify key elements of CNABMs that enable the qualitative assessment of critical success factors of CNABMs.

-

2)

A desk study on sugar-beet cultivation to develop an impression of how the identified key elements of CNABMS can be used in an agricultural application.

-

3)

Analysis of in-depth interviews with initiators of seven empirical case studies to further test and refine the framework for the evaluation of CNABMs.

Exploratory Literature Review

In an exploratory literature review, we followed an integrative literature approach [17] to examine scientific and other publications. The review was intended to generate insight into whether circular or sustainable business models that have been developed primarily for industrial applications can be applied in circular and nature-inclusive agricultural business models (CNABMs). We also identified key elements of CNABMs to develop an initial draft of a framework for assessing critical success factors for CNABMs. An integrative literature review is not intended as a systematic survey of all articles ever published on a certain topic or within a certain field of research. Rather, it aims to combine and integrate perspectives and insights from different scientific domains or research traditions [17].

Relevant literature was identified through a search in scientific databases (mainly Google Scholar) as well as through the recommendations of colleagues and peers. Instead of relying on fixed sets of keywords, we explored many different topics and research domains. Based on this initial collection of literature, we applied a snowball method to gather additional information through references cited in the articles from the initial collection. The explorative literature review was not meant to be exhaustive.

Testing the Initial Draft of the CNABM Framework in a Specific Agricultural Application

The applicability of the initial draft of the conceptual framework to assess critical success factors for CNABMs was first tested according to a desk study on the cultivation of sugar beets in the Netherlands and the by-products that remain after the sugar has been extracted from the beets. The by-products can be used for the production of green energy (bioethanol), bio-based elements or fibres, the maintenance of organic matter in the soil and/or the production of feed for dairy cows (beet pulp) [18, 19]. This exercise clearly demonstrated that the key elements of the CNABMs found in the literature can be recognised in each business strategy for sugar-beet cultivation.

Further Testing and Refining the CNABM Framework Based on Seven Empirical Case Studies

The next step in our research consisted of qualitatively analysing seven case studies involving livestock and arable farming as a further test of our conceptual framework for CNABMs based on empirical data.

To enhance understanding concerning the business models of circular or nature-inclusive farmers, we performed seven semi-structured in-depth interviews with livestock and arable farmers who were producing according to circular and/ or nature-inclusive methods. This type of interviewing is useful for answering more complicated research questions, including ‘why’ questions [20]. To this end, we developed an interview guide that would allow us to gather similar types of data from each participant [21] by providing the interviewers with guidance on which topics to discuss [22]. Based on the key elements of CNABMs as identified in the exploratory literature review and the desk study on sugar-beet cultivation (see Section “Exploratory Literature Review”), the interview guide included the following topics:

-

With regard to the social and physical context within which farmers operate:

-

Characteristics of the farm and the farmer

-

Barriers to and drivers of the realisation of CNABMs (adoption factors)

-

-

At the business level:

-

Questions related to the building blocks of CNABMs (value proposition, customer relations and segments, channels, activities, key resources, partners, cost structure, revenue streams and take-back infrastructure)

-

Strengths and weaknesses of the CNABMs

-

-

Sustainability impact

-

Questions related to positive and negative environmental, social and financial consequences

-

Each interview lasted 60–90 min. To ensure that every topic was discussed during the conversations, they were conducted by two interviewers. All interviews were recorded, with the permission of the farmers, and were transcribed verbatim. Each farmer signed a consent form granting permission to use the interviews for analysis.

For this research, we used a non-probability sampling technique known as purposive sampling. This method is characterised by making a deliberate choice of participants based on specific qualities [23]. Purposive sampling is typically used to identify information-rich cases in an efficient manner [24]. One disadvantage of this method is that it is subjective, thereby introducing bias into the choice of participants [23].

The sample for this case consisted of farmers in the Netherlands who were producing circular and/or nature-inclusive products. Some of these farmers were identified from a long list previously used by Hoes et al. [25]. The others were found through the network of researchers involved in the project, as well as through the website of Caring Farmers (https://caringfarmers.nl/), a community of farmers who produce or want to produce in a nature-inclusive and circular manner. Thirteen farmers were approached for an interview but only seven of them accepted the invitation. Six interviews were conducted online, and one interview was conducted live on the farm, at the farmer’s insistence. Each of the participating farmers received two €50 vouchers as an expression of gratitude for their time and effort answering the questions.

Each interview was analysed using the conceptual framework presented in the section “Towards a Conceptual Framework for Analyzing CNABMs”.

Results

This section is divided into four main parts. Following the structure of the Methods section, we start by presenting the results of the exploratory literature review. We describe how industrial applications can be applied in circular and nature-inclusive agricultural business models (CNABMs) (Section “General Circular Business Strategies also are Applicable in Agriculture”) and which key elements of CNABMs can be distinguished (Section “Key Elements for Circular and Nature-Inclusive Business Models”). This reveals key elements that should be distinguished to assess and reveal critical success factors of CNABMs, which we test in the sugar beet case (Section “Analysis of the Sugar Beet Case”). We then focus on the analysis of the in-depth interviews with initiators of seven empirical case studies to further test and refine the framework for evaluation of CNABMs (Section “Analysis of Seven Empirical Case Studies”). The section concludes with a presentation of our final conceptual framework for the evaluation of CNABMs (Section “Towards a Conceptual Framework for Analyzing CNABMs”).

Literature Review on Business Model Strategies and Elements of Circular and Nature-Inclusive Business Models

General Circular Business Strategies also are Applicable in Agriculture

The transition towards circular and nature-inclusive agricultural systems is part of a larger transition towards a circular economy. In the literature, several attempts have been made to describe circular business models (CBMs) [26,27,28] or sustainable business models (SBM) [29, 30]. Some studies on circular ‘industrial’ business models proceed from the notion of ‘R strategies’. As developed by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL), the R-ladder is composed of the following circular strategies [31]: (1) Refuse and Rethink, referring to renouncing of products and making more intensive use of products; (2) Reduce, referring to reducing the need for inputs by a more efficient fabrication of products or making products more efficient to use; (3) Reuse, referring to using products again; (4) Repair and Refurbish, referring to reusing product parts; (5) Recycle, referring to processing and reusing materials; and (6) Recover, referring to regaining energy from materials. The R strategies are also used by Lüdeke-Freund et al. [28], who propose six major ‘patterns’ (strategies) of circular economy business models (CEBM), which have the potential to support the closing of resource flows: (1) repair and maintenance; (2) reuse and redistribution; (3) refurbishment and remanufacturing; (4) recycling; (5) cascading and repurposing; and (6) organic feedstock business model patterns. The fifth and sixth CEBM strategies appear to be applicable to agriculture. Cascading and repurposing refer to the iterative use of the energy and material contents of physical objects/biomass (e.g. trees) and the efficient use of biomass (e.g. animal feed by valorisation of residuals of soy, beets or potatoes). Organic feedstock refers to the processing of organic residuals through biomass conversion, composting or anaerobic digestion and the generation of co-products from waste.

According to Lacy et al. [32], in a circular economy, growth is decoupled from the use of scarce resources through disruptive technology and business models based on longevity, renewability, reuse, repair, upgrade, refurbishment, capacity sharing and dematerialisation. The authors describe five different circular business strategies, including: (1) circular supplies, referring to the provision of renewable energy and the use of bio-based or fully recyclable input material to replace single-lifecycle inputs, and (2) resource recovery, referring to the recovery of useful resources or energy out of disposed products or by-products. For circular agriculture, renewable energy and bio-based materials are particularly important. For example, farmers can contribute to the provision of renewable energy by installing solar panels on roofs and, possibly, on land, and by allowing wind turbines on their land. They also can contribute to the use of bio-based material in bio-fermenters. For nature-inclusive agriculture, the central strategy is regeneration (recovery of the biosphere, and especially the soil).

A mapping tool developed by Bocken et al. [29] distinguishes nine sustainable business strategies: (1) maximise material and energy efficiency; (2) create value from ‘waste’; (3) deliver functionality, rather than ownership; (4) encourage sufficiency; (5) adopt a stewardship role; (6) re-purpose business for society/the environment; (7) integrate business into the community; (8) develop scalable solutions; and (9) radical innovation. Some of these strategies appear to be applicable to agriculture as well. For example, maximising material efficiency is actually already being broadly applied by farmers, as most of them use the services of contractors (including their machinery) for cultivating their land. In a way, this can be understood as a sharing platform for machinery. Furthermore, the production of plant proteins to replace animal proteins for a more efficient use of inputs is an example of maximising material efficiency, the use of residuals from the food industry for animal feed is an example of creating value from ‘waste’, and community-supported agriculture (CSA) is an example of integrating business into the community. In CSA, farmers and citizens share responsibility, risks and, in some cases, even ownership. Many such initiatives are currently emerging [33].

Based on the literature mentioned above, we further elaborated how specific circular or sustainable business strategies can be applied in CNABMs (see Appendix I).

Key Elements for Circular and Nature-Inclusive Business Models

In the previous section, we discussed circular business strategies that are applicable to CNABMs. In this section, we identify key elements necessary for a conceptual framework for CNABMs.

Take-back System and Adoption Factors

In a literature review, Lewandowski [26] identifies and classifies the characteristics of the circular economy according to the structure of a business model. To this end, the Business Model Canvas (BMC) of Ostenwalder and Pigneur [34] is adapted into a circular business model canvas by adding two new components to the model: a take-back system and adoption factors. The take-back system has its own channels and customer relations, and it is added to the common building blocks of the Business Model Canvas (value proposition, customer segments, customer relations, partners, key activities, key resources, channels, cost structure and revenue streams). For agricultural practices, the take-back system — or at least a kind of take-back system or infrastructure — seems applicable as well (e.g. to enable the recycling of nutrients between livestock and arable farms; to realise the use of renewable energy; to enable the use of residual flows from the food industry for animal feed; to compost organic waste from consumers; or to regain phosphate from human excreta). Adoption factors are important, as the transition towards circular business models must be supported by a variety of organisational capabilities and external factors. With regard to adoption factors, Lewandowski [26] includes the ‘PEST factors’, which were first described by Aguilar [35]: Political, Economic, Social and Technological factors that could influence business development. The PEST framework was later expanded into the PESTLE framework by Nandonde et al. [36], with the addition of Legal and Environmental factors. The PESTLE framework can be used as a diagnostic tool to analyse and monitor external macro-environmental factors that have an impact on business models [37]. It facilitates thinking about which factors are most likely to change and which are likely to have the most positive or negative impact on the performance of the CNABM business cases. To “unlock the circular economy”, Tura et al. [27] describe another framework comprising seven areas that partly overlap the PESTLE factors: environmental, economic, social, political and institutional, technological and informational, supply chain and organisational factors. A PESTLE analysis is sometimes combined with a SWOT approach [e.g. 38, 39, 40]. The benefit of this combination is that it allows the identification of positive and negative factors, both internal (strengths and weaknesses) and external (opportunities and threats).

Sustainability Impact

The circular economy — or, in our case, circular and nature-inclusive agriculture — is not always or not only sustainable. On the contrary, it sometimes raises new challenges, even if it can solve issues relating to sustainability [41]. For this reason, it is important to extend traditional business models (e.g. the BMC) to include elements related to sustainability [42, 43]. One example is the triple-layered BMC described by Joyce and Paquin [44]. These authors extend the BMC by adding an environmental layer, based on a lifecycle perspective, and a social layer, based on a stakeholder perspective. Taken together, the three layers of the business model make more explicit how an organisation generates multiple types of value: economic, environmental and social. They demonstrate other elements of the BMC, including social value, social impacts and social benefits, along with environmental impacts and benefits. Another extension to the BMC is presented by Antikainen and Valkokari [16], whose framework for evaluating the sustainability and circularity of business models distinguishes the business-ecosystem level (with trends, drivers and stakeholder involvement), the business level (with the building blocks of the BMC) and the sustainability-impact level (with environmental, social and business-related sustainability requirements and benefits).

Towards a Conceptual Framework for CNABMs

The literature presented in the previous section shows that three main elements are important to reveal critical success factors for CNABMs:

-

1.

The social and physical context, which includes the adoption factors based on Lewandowksi [26] and Tura et al. [27]

-

2.

The business level, which includes the building blocks of the BMC [28, 34], the circular building blocks [26] and the strengths and weaknesses from the SWOT analysis [38,39,40].

-

3.

The sustainability-impact level, which includes the positive and negative social, environmental and financial consequences of business models [44].

In the following sections we use these elements as a basis for a superficial analysis of the sugar-beet case and analyse the seven empirical case studies in more detail.

Analysis of the Sugar Beet Case

The analysis of the sugar-beet case was an initial test of our conceptual framework for the qualitative description of CNABMs. It is based on a desk study of the cultivation of sugar beets in the Netherlands and the by-products that remain after the sugar has been extracted from the beets. These by-products can be used for the production of green energy (bioethanol), bio-based elements or fibres, the maintenance of organic matter in the soil and/or the production of feed for dairy cows (beet pulp) [18, 19]. These uses of by-products fit respectively within the business strategies of repurposing, radical innovation, recycling and organic feedstock. For each business strategy, we superficially analysed the environmental, economic, political, legal and technological adoption factors described by Nandonde et al. [36], the business level based on the building blocks of the BMC and the take-back infrastructure [26, 35]; and the sustainability impact of the business models in terms of the positive and negative environmental and financial consequences of the business models’ sustainability [44]. This part of the study was intended to generate an initial impression of how the framework could work. We did not analyse the pilot-case study in much detail. Our findings regarding the adoption factors, the take-back system/infrastructure needed for the collection and processing of circular products (part of the business level), and the sustainability impact of the sugar-beet case are presented below. Further details regarding the building blocks of the BMC are presented in Appendix II. We did not include the SWOT analysis or the social adoption factors and sustainability impact, as doing so would have required a more detailed analysis.

Adoption Factors

Analysis of the PESTLE factors of sugar-beet cultivation indicates that important political issues include a possible sugar tax, green subsidies and political decisions concerning bio-based materials. The policy agenda for circular economy and nature-inclusive farming is relevant within this context as well. This is related to legal developments at the national and international level, including legislation on climate agreements and emissions. Adoption possibilities depend on technological progress. In particular, bio-based materials and the associated technology — including the infrastructure of materials and structural engineering — are still under development. This can lead to uncertainty, thereby delaying investments. Economic adoption factors concern the prices of fossil energy (which help to determine green energy profits), costs of producing bio-based materials compared to those of traditional materials, and the cost of energy in the production of animal feed based on beet pulp. Although leaving remnants of beet production on the land is cost-efficient (as it eliminates the need to remove it), the revenues become visible only in the long term. Environmental adoption factors concern the need for renewable energy, bio-based materials and reduction of biodiversity loss in the soil and on the land.

Take-back System/Infrastructure for the Production of Bio-Ethanol and Bio-Based Products

Given the essential importance of reusing residual flows to CNABMs, this section addresses the take-back system/infrastructure, which is apparently important to the production of bio-ethanol or bio-based materials or the production of beet pulp for animal feed. In addition to the harvesting of sugar beets, the production of bio-ethanol, bio-based materials and animal feed entail the processing of beets into bio-ethanol, bio-based materials and beet pulp. It also includes making the products available to the energy, chemical and feed industries. A take-back system does not play an important role in business strategies based on leaving the beet remnants on the land.

Sustainability Impact

The four circular and/or nature-inclusive strategies for the sugar-beet sector include a variety of benefits and, in some cases, deficiencies. Sugar beets can be used for the production of ethanol as an alternative to fossil energy, as well as for bio-based materials as an alternative to non-renewable resources. These strategies are suitable to a circular economy. Furthermore, crop remnants can be either left on the soil to improve organic matter or used as feed stock as an alternative to feed imports. These uses are consistent with nature-inclusive agriculture. The environmental advantages of the four strategies include the use of renewable resources instead of fossil resources, the improvement of soil structure due to greater soil biodiversity, and a decrease in feed imports and a corresponding decrease in the loss of biodiversity elsewhere in the world. The strategies are subject to shortcomings as well, however, including the CO2 emissions generated by renewable energy from bio-based resources and energy consumption from both the production of bio-based materials and the drying of beet pulp for feed production.

The results are also diverse from an economic perspective. The profitability of ethanol, bio-based materials and beet-residue feed depends solely on energy prices, whereas the profitability of bio-based materials also depends on the price of traditional materials, and the profitability of beet-residue feed also depends on the price of imported feed.

The impacts of the strategies result in increased sustainability within a wide range of sectors, both outside agriculture (e.g. the energy and chemical sectors) and within agriculture (the arable and livestock sectors).

Lessons from the Sugar-Beet Case

As demonstrated by our approach, CNABMs (in this case, relating to the cultivation of sugar beets in the Netherlands) can be unravelled in several business strategies. A variety of circular elements can be recognised in these strategies, including the recycling, upgrading or remanufacturing of products, components, materials or waste. Additional values for new stakeholders can be created (e.g. through strategies for the production of bioethanol and bio-based elements or fibres), and values for existing stakeholders are utilised as much as possible (e.g. in strategies for the maintenance of organic matter in the soil and/or the production of beet-pulp-based feed for dairy cows). The choice of one business strategy does not necessarily exclude the others. If beet remnants are left on the land or if beet pulp is used for animal feed, the beets can still be used in the production of bio-ethanol or bio-based materials. In contrast, if beets are used for the production of bio-ethanol or bio-based material (or sugar), they can no longer be used for other purposes. The adoption factors are the most important part of our conceptual framework, as they provide insight into the barriers and drivers associated with specific business strategies. In our analysis (which is admittedly superficial), leaving the beet remnants on the land seems the most beneficial, as it seems to have only positive effects (on the quality and biodiversity of the soil). Moreover, it involves only beet waste, such that the beets still can be used for the production of bio-ethanol or bio-based materials (or sugar). Within this context, nature-inclusive solutions (leaving the beet remnants on the land to improve soil quality) are accompanied by circular solutions (upgrading beets for the production of green energy or bio-based materials).

Analysis of Seven Empirical Case Studies

The Farmers and their Farms

Farm Activities and Features

All farmers we interviewed had farms with nature-inclusive and circular elements. Five of the farms were organic. Of the non-organic farmers, one fed the animals with residuals that are difficult to obtain from non-organic sources, let alone from organic sources. All but one of the farmers kept beef cattle (2 farms), dairy cattle (2 farms), pigs (1 farm) or broiler chickens (1 farm). The farm with the broiler chickens also had arable land. The farmer without livestock had a regenerative arable farm. Examples of side activities undertaken at the farms included farm shops, hospitality activities, education, free-range laying hens, self-made dairy products, grain production for local mills, and excursions. The farms were dispersed throughout the country. Most of the farmers interviewed had between 50 and 100 ha of utilized agricultural area (UAA), except for one farm that was very small, in order to maintain the ‘hobby farmer’ statusFootnote 1.

CNABM Strategies

The CNABM strategies are summarised in Table 1. In all cases, the farmers were reducing inputs and integrating business into the community in various ways. The most frequently mentioned practices were short supply chains through the exploitation of farm shops, collaboration between farmers, and education and excursions. One farmer was reducing food waste by collecting it at local bakeries and retailers and feeding it to the animals, which were living under high animal welfare standards. In all but one of the cases (a conventional farm), the farmers had rejected common practices, and five of the farmers had organic, nature-inclusive or regenerative farms, and they thus did not use any chemical pesticides or artificial fertilisers. They were also contributing to the repair and maintenance of the natural environment. Four of these farmers were also applying nature conservation. In four cases, sustainable energy was produced by means of solar panels and wind turbines (and two other farmers had plans to implement after the realising a new stall or replacing an old roof containing asbestos). All of the farmers interviewed were applying multiple CNABM strategies.

Social and Physical Context – Adoption Factors

The barriers and drivers mentioned during the interviews with the farmers are listed in Table 2. One barrier mentioned by several interviewees was that farmers tend to feel that they are too far ahead of their time and that they are often not eligible for sustainability subsidies, because their approach deviates too much from the norm:

Actually, I often feel that I’m too far ahead of my time. In addition, policies and such are not yet applicable to what I do. Subsidies aren’t suitable. (ID-05)

This is especially discouraging because, in many cases, the revenue models are hardly sufficient, due to the small scale of the business combined with the high investments needed to realise the transition. For example, as according to one farmer:

It’s very difficult. It also costs a lot of money. And yes, I have to pay for it all myself, based on a revenue model that’s actually insufficient. (ID-01)

Barriers at the social level included negative social pressure from other farmers in the surroundings and complaints from citizens:

Well, there was an open day, and farmers and everyone could just drop by. I thought I’d go have a look, and I signed up for it. But the farmer was so suspicious that he Googled everyone, and then he came to me. And then he called me on the phone to say that I couldn’t come, because they’re too different. … He can of course think whatever he wants about that, but I think it’s a shame that someone is already avoiding the discussion. (ID-04).

My wife has had a lot of trouble because of that. On the other hand, it also hurts me that colleagues can just leave you out in the cold and judge you — not directly to your face, but you hear about it anyway. I think that’s the most important obstacle in the entire transition. The finance and the regulations, that can be adjusted. We’ve got a long way to go, but it can be done. But the social side is very difficult. (ID-03)

With regard to technological innovations, the investments that early adopters must make in learning are not reimbursed:

So, actually, I’ve had very little subsidy. A few tens of thousands of euros for a prospect involving millions, of course. … I’ve paid quite a bit of learning and development costs. … In general, I get good prices, good agreements with my customers. I’ve just done a really good job arranging things. But the costs of learning and development —that part has yet to be covered. (ID-05).

In many cases, special initiatives do not correspond to legislation developed for conventional farms. To avoid an excessive and overly complicated administrative burden, one farmer purposely kept the number of animals low, thereby remaining a ‘hobby farmer’. Most of the farmers interviewed were also concerned by the policy uncertainty surrounding the current nitrogen crisis in the Netherlands. This is making it unclear to farmers whether they will be able to remain on their farms, especially if they are located near areas with vulnerable nature (‘Natura 2000 areas’).Footnote 2

One environmental barrier mentioned is soil, which must recover from intensive use by previous farmers:

The soil here has been spoiled. Hey, we all did that. Yeah, so why do I have to pay for that, to fix what went wrong? Was there a conventional farmer here in the past? Yes, with fertilisers, pesticides and corn farming. (ID-01).

One important condition for circular farming is the supply of residual flows (e.g. for animal feed), which are often limited. Moreover, few take-back systems have been developed to date.

In addition to these barriers, the farmers mentioned drivers of the adoption of circular and nature-inclusive business models. All interviewees had taken initiatives that fit within the vision of the Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Safety concerning circular, nature-inclusive and/or regenerative agriculture. Most of them were also making use of innovative business models, different revenue streams and increased interest in local products. One important stimulus is the common awareness of the climate crisis and the need for sustainability, as well as of the need for agricultural practices to be more embedded within society. As described by one farmer:

We’re close to an urban area. Hundreds of thousands of people live here, 1.5 million or so. The connection between the city and the countryside should soon be improved. And then I’ll have a very nice spot here. We have to try to feed the city directly. So, my responsibility is to produce as much food as possible. The main difference, however, is that you have to build very clear boundaries into your system. (ID-05).

Social media and websites are often used for purposes of both information and sales. Whereas the lack of financial (or other) incentives was mentioned as a barrier, the availability of supportive funds and subsidies was mentioned as a driver. Environmental drivers are essential: soil-life recovery, increased biodiversity, discontinuing the use of pesticides and artificial fertilisers, minimising the use of other inputs and working to close nutrient cycles. One advantage these pioneers had was that there was sufficient demand for organic manure and organic feed. Many of these farmers had wide networks involving other entrepreneurs, citizens, nature organisations or other entities.

Business Level

Building Blocks

Examination of the building blocks (Table 3) reveals that, in most cases, added value was realised by the production of high-quality arable products and meat (from animals kept under high animal-welfare standards), renewable energy and nature conservation. Other ways to create added value included educational or recreational activities and the production of bio-based building materials. Most agricultural products were sold in the farmers’ own farm shops or local farm shops nearby. This is illustrated by the following quotations:

So, I always say, they shouldn’t come here for cheap products, but more to know where it comes from and for the taste. And yes, it’s direct [from farmer to consumer, Ed.]. This is often also the experience of people who like to come here, to hear something about how things go on a farm. And yes, actually — those are a few reasons why it adds value for consumers. (ID-02)

We don’t want supermarkets; we don’t want big stores. I do indeed prefer to stick to farm shops, and to have a point of sale here at home. … What my customers like is seeing it with their own eyes, hearing the story first-hand … That makes it worthwhile for everyone. (ID-04)

In most cases, the target customers were local and critical consumers. Partners and stakeholders included other — usually organic — farmers (for the provision of calves or the exchange of grains and manure), local bakeries and retailers (for food-waste streams) and nature organisations and landowners for purposes of nature conservation. Value-creation processes included agricultural processes, as well as processes for manufacturing bio-based materials and for producing renewable energy from solar panels or wind turbines and making it available to the electricity network. The most important resources in the cases came from crowd funding and farm funding; pasture and arable land; the availability of nature reserves and forest area; and sun and wind. Most additional costs were for additional inputs. Products and services were usually delivered through existing channels. In some cases, however, farmers delivered products to local farm shops themselves or — in one case — personally collected food waste from bakeries and supermarkets. No additional take-back system or infrastructure was necessary in any of our seven cases.

Strengths and Weaknesses

A SWOT analysis is a framework for evaluating a company’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in order to uncover possible blind spots and improve its position within the market. Given the considerable overlap between opportunities and threats in a SWOT analysis and the drivers and barriers (as mentioned in Table 2), we focus only on strengths and weaknesses, which are used to evaluate internal factors within a firm that contribute to its success or vulnerability. All interviewees mentioned that they were working with new, innovative business models, often with several revenue streams and selling at local markets, thereby exploiting the benefits of short supply chains and limiting the costs as much as possible:

What I also think is very important is that the farm should just produce locally, including in terms of feed and, thus, in terms of feed and straw, I'm just completely self-sufficient. All my own stuff. And I like it when it’s also, but also kind of important that it’s marketed in the region. ... It's also a strong marketing story, but, for myself, I also believe it’s just a nice model. (ID-01)

All calves that are born from those dairy cows, they stay on the farm for 2½ years, so, in fact, we’re eliminating veal-calf farming. And we feed them [the calves, ed.] with our own feed that was produced on the land we take care of. And we don’t use manure from outside our farm or artificial fertilisers [...]’ (ID-07).

The revenue models are often vulnerable, however, due to small scale, which also makes it difficult to take risks and try out new things. Furthermore, the financing of innovations is a challenge, given that traditional banks are reluctant to finance unfamiliar prospects:

Financing the transition is an issue, but it’s manageable. For the extensification of land, for the stables, for barn adjustments, however, then I’m talking about large amounts. A farmer just doesn’t get approval from the bank for that, because there’s not a sufficient revenue model behind it. Those banks don’t have an Excel sheet for organic farms yet. (ID-03)

Another vulnerability we observed in one case was the farmer’s dependency on residual streams from the food industry. In addition to requiring a large amount of effort from the farmer to collect these residuals, it also caused uncertainty in terms of the availability of the residual streams.

Sustainability Impact

Sustainability impact focuses on consequences for society, instead of at the business level. The consequences can be either positive or negative, and they can be felt at the social, environmental or financial level (Table 5). Positive social effects mentioned included farms becoming more embedded within society and activities in various areas of society (e.g. consultation bodies and education projects). As remarked by one farmer:

I can envision a very nice image of a broadened agriculture. The core task is thus to produce as much food as possible. But every company is responsible for making that connection with citizens, with society. And we want to realise this in a very concrete way. And the more engaged you become in what I’m doing, the more you’ll find that, the more important it will be to you. The ordinary, average farmers … think that having citizens living in the countryside is a real problem. … But it’s precisely this connection that we’re constantly seeking with those citizens. (ID-05)

Negative social impacts mentioned by the interviewees included complaints from citizens and citizens who are overprotective. New approaches raise questions, especially when those approaches involve animals:

Look, we’ve got cows walking around running in the city practically right up to the city centre. We went there three times last week, because people were constantly calling the nature organisation saying that this cow is sick and that calf is drinking. And that cow has such a huge udder and it’s not going to be okay. And that cow isn’t getting back up, and it’s really not going to be okay. You go there three times for nothing. Because, once you come, the cow walks away and the calf is at the front of the herd. That means that the cow is producing enough, and so it means that some of it is getting into the calf. (ID-06).

One positive impact of nature-inclusive agriculture is that it often contributes to an attractive landscape. In environmental terms, these strategies have a positive impact on soil and biodiversity in general, in part because few or no pesticides and artificial fertilisers are used. This helps to close nutrient cycles. In the interviews, farmers noted:

The importance of those resting crops, the importance of that grain, that field bean and the other crops — it’s thus not just for feeding the people and producing cattle feed. It’s also for preserving the soil, for the quality of the soil and for the quality of the products that come from it. (ID-02)

I think we’re serving society, because if we weren’t doing this, they’d have to go into the nature reserves with machines, and that would disrupt everything. You can’t let everything grow and take over. That doesn’t work. And because our animals graze, the effects are scaled up. Flowers are coming back that haven’t grown there for years. If you walk through the nature reserve nearby, you can really smell all kinds of things. So, all kinds of things are growing here, ground ivy, water mint. (ID-06)

One negative environmental impact mentioned by some farmers concerned the transport needed when customers visit the farm shop or if farmers have to deliver local products to customers or collect food-industry residuals to feed their animals. As observed by one farmer:

People are indeed always coming to pick it up. I’ve tried to arrange it with a parcel service, but they have absolutely no clue about sending meat. … But, you could obviously pick it up yourself at an appointed time, and yes, we do drive all over the place with the van. … Yes, so, in terms of diesel consumption, I would like to do better. (ID-04).

Moreover, environmentally conscious farmers continue to use polluting products, even if they would prefer not to:

Because that’s also an issue here on the farm. We have those round bales with plastic, and we have silage with plastic. Well, I’d prefer to have as little plastic as possible, because — apart from the fact that it costs oil and energy, it also creates a huge mess, doesn’t it? (ID-07)

Positive financial consequences include lower costs for inputs:

We obviously still have to deal with a bank, which we’d like to get rid of, but that takes some time. But otherwise … a lot of input from regular companies — I actually have nothing to do with that. I don’t buy artificial fertilizer, no chemicals and no concentrates either. [...] And this system of animal husbandry with this breed of cows that we have, it actually ensures extremely low veterinary costs. (ID-07)

Negative financial consequences are related to vulnerabilities in the business models, and the difficulties that farmers face in acquiring funding for their initiatives and for the transition in general. This is despite the many benefits that these farmers perceive from these developments.

Yes, financing really is the biggest challenge. It should really be at the top of the list. It costs a fortune to make the change. How are we going to ensure that a whole group of farmers can start making that transition? ... from a few farmers doing it at their own cost or their own initiative or their own risk. Yes, to making it attractive, making it challenging to develop very seriously in that direction. And we’re still so far away from it that I don’t even know myself. But that’s something for the province and so on. And there are huge opportunities there. If you can make that happen, I’m still convinced that it could be very inexpensive for society as a whole to have healthy food from a healthy food system, with a healthy revenue model for the farmer and a beautiful landscape, with much less negative impact on the entire environment. (ID-05).

One important factor is that farmers have low costs, given the reluctance of traditional banks to finance their initiatives:

Mainstream farmers who are all up to their ears in debt with all kinds of constructions with feed suppliers and banks. And we just started doing this with our own money. We don’t have a bank breathing down our necks. What’s more, we wanted to make everything more sustainable this year with solar panels, and the bank just wouldn’t give us a red cent. (ID-06).

Towards a conceptual framework for analyzing CNABMs

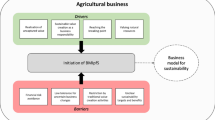

The exploratory literature review (Section “Literature Review on Business Model Strategies 188 and Elements of Circular and Nature Inclusive Business Models”), the findings from the sugar-beet case (Section “Analysis of the Sugar Beet Case”) and the seven empirical cases (Section “Analysis of Seven Empirical Case Studies”) together led to the conceptual framework for analysing CNABMs, as shown in Fig. 2. The framework has been adapted from Antikainen and Valkokari [16]. We distinguish three key elements:

-

1.

The social and physical context, which includes the adoption factors (based on Lewandowksi [26] and Tura et al. [27]).

-

2.

The business level, which includes the building blocks of the BMC [28, 34], the circular building blocks [19] and the strengths and weaknesses from the SWOT analysis [38,39,40]. (The opportunities and threats identified in the SWOT analysis are not discussed at this point, as they overlap with the adoption factors in the first part of the framework.)

-

3.

The sustainability-impact context, which includes the positive and negative social, environmental and financial consequences of business models [44].

(Adapted from Antikainen and Valkokari [16])

Conceptual framework for Circular and Nature-inclusive or Nature-positive Agricultural Business Models (CNABMs)

It is important to note that this framework can also be applied to other types of sustainable agriculture.

Discussion

In this paper, we describe and test a conceptual framework for assisting farmers in developing their future businesses towards agricultural business models that are more circular and nature-inclusive. Proceeding from existing literature and the framework developed by Antikainen and Valkokari [16], we argue that, when identifying critical success factors for the implementation of nature-inclusive and circular agricultural business models (CNABMs) (or more sustainable business models in general), (1) it is important to consider the barriers and drivers in the social and physical contexts within which entrepreneurs involved in such business models must operate (‘adoption factors’); (2) sustainable business models should go beyond delivering economic value and include a consideration of other forms of value for a broader range of stakeholders. Moreover, attention should be paid to strengths and weaknesses of the business model; and (3) traditional business model tools (e.g. the BMC) should be extended to include elements relating to sustainability (sustainability impact).

We performed an initial test of the framework within the context of sugar-beet cultivation in the Netherlands. The results show that several business models are used simultaneously for processing sugar beets and their by-products, each with its own social and physical contexts, building blocks, strengths and weaknesses, and sustainability impact.

In the next step of the research, the conceptual framework was further tested in seven empirical case studies in arable and livestock farming. This provided additional insight in the applicability of the framework. In the following sections, we elaborate on this for the three key elements of the framework. The discussion includes a description of the most striking results.

Barriers and Drivers of CNABMs – Adoption Factors

Farmers seeking to realise circular or nature-inclusive farms — or, more generally, farmers seeking to shift to more sustainable farming methods — perceive a variety of barriers (negative adoption factors) to doing this, as well as drivers (positive adoption factors) of the process. This observation emerged from our interviews, but it has also been reported in the literature. Examples of barriers mentioned by our interviewees include restrictive legislation, dependence on short-term land-lease contracts, a lack of critical consumers who are willing to pay for sustainable products, negative social pressure from citizens and other farmers in the surroundings, uncertainty about the government’s plans concerning the nitrogen crisis and climate change, and a lack of knowledge about new sustainable farming methods. Other examples include a wide range of financial factors, like revenue models that are hardly sufficient due to small scale, the excessive investments required to realise the transition, ‘traditional’ banks that prefer not to invest in special initiatives, and restricted market access (e.g. fulfilling demands for organic farming but not being able to access the market for organic products). In the Dutch context, other authors also have identified complex and overlapping regulations and a lack of governmental support as barriers to circular farming, as well as a lack of knowledge, a lack of social support and various economic factors [45,46,47,48,49,50]. Uncertainty about the government’s plans concerning the nitrogen crisis and climate change is a continuing point of concern for Dutch farmers, regardless of their production methods [50]. Policy in this regard is shifting, and the accompanying uncertainty has far-reaching effects on the financial performance and business development of farms [49]. In the international context, a lack of social support, a lack of knowledge, economic factors and complex rules and regulations are also mentioned as barriers to the transition towards more sustainable farming systems, [51,52,53,54,55,56]

In addition to barriers, adoption factors include various drivers. Examples mentioned by the farmers in our study are: awareness of the need for sustainability, the availability of supportive funds and subsidies (albeit that some of the interviewed farmers mentioned that their initiatives were too far ahead for obtaining these subsidies), possibilities for knowledge development in the area of nature-based and circular solutions and consumer concerns about climate change and the corresponding increase of interest in local products. These kinds of drivers have also been mentioned in several other studies [57,58,59].

As also noted by many authors, the context within which farmers have to operate is important when seeking to understand their decision-making [45, 58, 60,61,62,63,64].

New Values and Strengths and Weaknesses of CNABMs

Circular and nature-inclusive agricultural business models (CNABMs) — or, more generally, sustainable business models — concern more than the delivery of economic value. They should also consider other forms of value for a broader range of stakeholders [16, 29, 41,42,43,44].

New values delivered by the farms addressed in this study include experiencing nature and farm life, embeddedness in the local community, cascading (the sequential use of resources that would otherwise be destroyed) and the reduction of plant-based food waste used to feed animals. These kinds of value do not receive much attention in ‘normal’ or traditional business models. They have also been mentioned in other studies about circular agriculture [25, 42, 43, 46, 65].

In the part of our conceptual framework that addresses the business level, we distinguish two elements in addition to the building blocks of the BMC: the take-back system described by Lewandowski [26] and the strengths and weaknesses identified in the SWOT analysis, as also described by Loizia [38], Srdjevic et al. [39] and Fernandes [40]. In most of the cases we examined, a take-back system was not necessary, except in one case that involved the collection of residual streams from the food industry to feed animals, which required considerable effort from the farmer involved. In the sugar-beet case, a take-back system is needed to collect and process the beet and their residuals, as well as to convert them into bio-based energy or sugar (beet), into fibres for cloth or building materials (residuals) or into beet pulp for the feed industry. According to Nygaard Uhrenholt et al. [66], product take-back systems are fundamental to the circular economy, as they focus on recovering value by taking back products to be recycled, re-manufactured or refurbished. The authors state that, in practice, such take-back systems are often included only in small/pilot-scale projects or have difficulty becoming financially viable, thereby posing an obstacle to the widespread adoption of circular economy.

The addition of strengths and weaknesses to the CNABM framework appeared to be useful because it can provide insight into the strong points of farms (e.g. proximity to villages or location in a tourist area, which makes it easier to attract consumers to the farm), as well as into their vulnerabilities (e.g. dependence on risky farm-funding methods or dependence on the availability of residuals from the food industry). These insights could help farmers and their advisors improve their ability to assess the likelihood that new farm initiatives will or will not succeed. As noted by Netshipale et al. [67], acknowledging the diversity in the strengths and weaknesses of farms is essential if land reform is to play a critical role in rural development. Moreover, insight into such strengths and weaknesses could facilitate the identification of developmental pathways for various types of farms. Within certain contexts, it could also contribute to the success of farms. This possibility is also illustrated by Radadya et al. [68] regarding access to agricultural markets. In addition, Liu et al. [69] identify the availability of land, the adaptability of energy crops and the development of the rural economy as strengths of producing bio-energy on marginal land. Weaknesses include economic viability and environmental impact, along with concerns relating to equity and gender [69].

Especially in circular business models, greater interdependence between stakeholders can play a role [45, 54, 70]. For example, this could be the case if more social cohesion were to emerge between farmers and consumers (strength) or if a farmer were to become dependent on residuals from the food industry (weakness).

Sustainability Impact of CNABMs

One important aspect of assessing CNABMs or sustainable business models is the need to consider their sustainability impact [44, 71,72,73]. This is also important within the context of the circular economy [74]. For this reason, our conceptual framework for CNABMs distinguishes positive and negative social, environmental and financial consequences. These consequences can be linked to the ‘classic’ triple bottom line (TBL) sustainability concept of ‘People, Planet and Profit’. This concept was first introduced by Elkington [75, 71

Examples of positive consequences of the CNABMs we studied include embeddedness in society (social impact) due to short supply chains and direct contacts between farmers and consumers; contribution to healthier soil, nature and biodiversity (environmental impact); and the realisation of a greater share from consumer prices (economic impact). Our cases also revealed negative impacts. Examples include complaints from consumers who do not understand why farm animals are kept under more natural circumstances and consumers who are concerned about farm animals being kept to close to their homes (social impact), the use of diesel, petrol and plastics and, in some cases, greater transport distances for farmers who must travel throughout the country to deliver their products or for consumers who must drive further to reach the farm shops (environmental impact) and, possibly, riskier funding for farm initiatives (financial impact).

Comparable positive and negative impacts of short supply chains based on circular economy have also been mentioned by Kiss et al. [74]. According to these authors, the positive sustainability attributes (whether actual or supposed) of short supply chains are based primarily on extensive production methods and short transport distances. From other perspectives, however, the economic and environmental sustainability of the short chains is questionable, due to their possible de-concentration, leading to smaller freights and greater distances travelled by customers. For this reason, Kiss et al. [74] state that, despite the many potential benefits short supply chains may have for sustainability, it remains important to consider that local systems cannot be automatically identified as ‘good practices’. Comparable results are mentioned by Malak-Rawlikowska et al. [76], who state that participation in short supply chains is beneficial to producers from an economic perspective, as it allows them to capture a large proportion of margin that would otherwise be absorbed by different intermediaries. On the other hand, however,’longer’ supply channels generate lower environmental impact per unit of production when measured in terms of ‘food miles’ and ‘carbon footprint’ [76]. Moreover, consumers must be willing to accept higher purchase prices for convenience and specific product attributes, and the aggregate transportation effort that is characteristic of short chains is not efficient from the perspective of environmental sustainability, especially considering that such items usually constitute only a small proportion of a customer’s overall diet.

Limitations of the Study

Despite its contributions to unravelling CNABMs (or other sustainable business models), our study is subject to a number of limitations. The conceptual framework is based on an exploratory literature review and not on a systematic literature review, as that would have exceeded the scope of this exploratory conceptual article. Moreover, our test of the framework was based on a desk study on sugar-beet cultivation and by-products, along with seven in-depth empirical case studies. While this offers an overview of the potential application of such a framework, further research is required to test and refine the framework. For example, future studies could be based on multiple workshops with farmers, farmer advisers and other stakeholders who are working together to enhance the sustainability of the agricultural sector whilst ensuring a profitable revenue model for the farmers involved.

As evidenced by the literature [16, 29, 41, 44], a general conceptual framework for more sustainable business models is not unique. To the best of our knowledge, however, no conceptual framework has been described to date that can reveal critical success factors for circular and nature-inclusive agricultural business models. This paper therefore constitutes a valuable contribution to the existing literature on business models.

Conclusions

This paper presents a conceptual framework that could assist farmers, their advisers and, potentially funding organisations in identifying critical success factors for the implementation of circular and nature-inclusive business models (CNABMs). The framework was based on a synthesis of existing literature, a desk-study on sugar-beet cultivation and seven empirical case studies based on in-depth interviews with livestock and/ or arable farmers who produced in a circular and/ or nature-inclusive way.

As demonstrated by the results of our study, the conceptual framework is useful for identifying critical success factors for the implementation of combined circular and nature-inclusive or other sustainable business models in a qualitative way. The framework enables the identification of barriers to and drivers of CNABMs (adoption factors), as well as the building blocks required to cover the financial side of the business model. Furthermore, it allows for the identification of the strengths and — especially — weaknesses of the models, thereby revealing their vulnerabilities. The framework also makes it possible to highlight the possible positive and negative financial, environmental, and social consequences of specific business models (sustainability impact). The approach is likely to be beneficial to policymakers and business advisers by providing insight into the capabilities of companies in a clear and structured manner.

The paper illustrates that the identification of critical success factors for the implementation of circular, nature-inclusive and other sustainable agricultural business models requires considering both the positive and negative impacts of these models.

Data availability

A data availability statement is not applicable for this paper. We cannot share the data.

Notes

For reasons of anonymity, we cannot specify these farms any further.

Natura 2000 is a European network of protected natural areas. In these Natura 2000 areas, certain animals, plants and their natural habitats are protected to preserve biodiversity (species diversity).

References

Arora NK (2018) Agricultural and food security. Environ Sustain 1:217–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-018-00032-2

Fresco LO, Geerling-Eiff F, Hoes AC, Van Wassenaer L, Poppe KJ, Van der Vorst JGAJ (2021) Sustainable food systems: do agricultural economists have a role? Eur Rev Agric Econ jbab026. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbab026

Ritchie H, Roser M (2020). Environmental impacts of food production. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved September 2023 from https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food

Hollander A, Temme EHM, Zijp M (2016). The environmental sustainability of the Dutch diet. Background report to ‘What is on our plate? Safe, healthy and sustainable diets in the Netherlands. RIVM Report 2016–0198. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.23632.92162

LNV (2018) Agriculture, nature and food: valuable and connected. Dutch ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Den Haag. Retrieved March 2019 from https://www.government.nl/ministries/ministry-of-agriculture-nature-and-food-quality/documents/policy-notes/2018/11/19/vision-ministry-of-agriculture-nature-and-food-quality---english

Transitie-agenda Circulaire Economie (2018) Biomassa & Voedsel - Food for Thought. Ministerie van infrastructuur en waterstaat. pdf (overheid.nl). Retrieved September 2022

Runhaar H (2017) Governing the transition towards ‘nature-inclusive’ agriculture: insights from the Netherlands. Int J Agric Sustain 15(4):340–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1312096

Church R, Walsh M, Engel K, Vaupel M (2022). A biodiversity guide for business. Umweltstiftung WWF-Deutschland. wwf___a_biodiversity_guide_for_business___final_for_distribution_23052022.pdf (panda.org). Retrieved August 2024

World Economic Forum (2023) Nature Positive: Role of the cement and concrete sector, insight report. In collaboration with Oliver Wyman. WEF_Nature_Positive_Role_of_the_Cement_and_Concrete_Sector_2023.pdf (weforum.org). Retrieved August 2024

European Commission (2023) European business & nature summit 2023. Biodiversity: Businesses pledge to protect nature at Milan summit - European Commission (europa.eu). Retrieved August 2024

Termeer K (2019) Het bewerkstelligen van een transitie naar kringlooplandbouw. Briefing transitie naar kringlooplandbouw. Notitie opgesteld op verzoek van de Tweede Kamer Commissie LNV. Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen. Retrieved March 2020 from https://www.wur.nl/en/show/Termeer-C.J.A.M.-2019-Expertpaper-over-het-bewerkstelligen-van-een-transitie-naar-kringlooplandbouw.htm

Taskforce “Verdienvermogen Kringlooplandbouw” chair Maij H (2019) Goed boeren kunnen boeren niet alleen. Opdrachtgever: ministerie van LNV. Goed+boeren+kunnen+boeren+niet+alleen.pdf. Retrieved September 2022

European Commission (2018) Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, A sustainable bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the connection between economy, society and the environment: Updated bioeconomy strategy. European Commission. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/792130

Bröring S, Vanacker A (2022) Designing Business Models for the Bioeconomy: What are the major challenges? EFB Bioeconomy Journal 2:100032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioeco.2022.100032

Donner M, De Vries H (2021) How to innovate business models for a circular bio-economy? Bus Strateg Environ 30(4):1932–1947. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2725

Antikainen M, Valkokari K (2016) A framework for sustainable circular business model innovation. Technol Innovation Manag Rev 6(7):5–12. http://timreview.ca/article/1000

Snyder H (2019) Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 104:333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Smit AB, Janssens SRM (2016) Reststromen suikerketen (Residual flows sugar supply chain). Factsheet, LEI Wageningen UR, Wageningen. Retrieved September 2022 from https://edepot.wur.nl/368098

Gielen P (2021) Suiker als ideale biogrondstof voor chemie. Agro&Chemie, 8 april 2021. https://www.agro-chemie.nl/artikelen/suiker-als-ideale-biogrondstof-voor-chemie/. assessed 21 December 2021. https://edepot.wur.nl/357823

Fylan F (2005) Semi-structured interviewing. A handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology 5(2):65–78

Holloway I, Wheeler S (2010) Qualitative Research in Nursing and Health Care, 3rd edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, Ames, Iowa

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B (2008) Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J 204(6):291–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 5(1):1–4

Patton MQ (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Hoes AC, Slegers M, Savelkouls C, Beldman A, Lakner D, Puister-Jansen L (2020) Toekomstige Voedselproductie: Een Portret van Pionierende Boeren die Bijdragen aan Kringlooplandbouw in Nederland (Future Food Production: A Portrait of Pioneering Farmers who Contribute to Circular Agriculture in the Netherlands); Wageningen Economic Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. Retrieved September 2020 from https://edepot.wur.nl/519070

Lewandowski M (2016) Designing the business models for circular economy – towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 8:43. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010043

Tura N, Hanski J, Ahola T, SthåS M, Piiparinen S, Valkokari P (2019) Unlocking circular business: a framework of barriers and drivers. J Clean Prod 212(1):90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.202

Lüdeke-Freund F, Gold S, Bocken NMP (2019) A review and typology of circular economy business model patterns. J Ind Ecol 23(1):36–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12763

Bocken NMP, Short S, Rana P, Evans S (2013) A value mapping tool for sustainable modelling. Corp Gov 13(5):482–497. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-06-2013-0078

Lüdeke-Freund F, Carroux S, Joyce A, Massa L, Breuer H (2018) The sustainable business model pattern taxonomy – 45 patterns to support sustainability-oriented business model innovation. Sustainable production and consumption 15:145–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2018.06.004

Kishna M, Rood T, Prins AG (2019) Achtergrondrapport bij circulaire economie in kaart. Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving, Den Haag (PBL), publicatienummer 3403, Den Haag. Retrieved September 2022 from https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/pbl-2019-achtergrondrapport-bij-circulaire-economie-in-kaart-3403_1.pdf

Lacy P, Keeble J, McNamara R (2014) Circular advantage. Innovative business models and technologies to create value in a world without limits to growth. Accenture Strategy. https://www.accenture.com/t20150523t053139__w__/us-en/_acnmedia/accenture/conversion-assets/dotcom/documents/global/pdf/strategy_6/accenture-circular-advantage-innovative-business-models-technologies-value-growth.pdf

Jonker J, Faber N (2021) Business model archetypes. Organizing for sustainability. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78157-6_6

Osterwalder A, Pigneur Y (2010) Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Wiley, New Jersey

Aguilar FJ (1967) Scanning the business environment. Macmillan, New York

Nandonde FA (2019) A PESTLE analysis of international retailing in the East African Community. Glob Bus Organ Excell 38(4):54–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/JOE.21935.ISSN1932-2054.WikidataQ98854703

Gillespie A (2016) Foundations of Economics. OUP Catalogue. (I used Gilsing R, Turetken O, Grefen P, Ozkan B, Adali, O E (2022) Business Model Evaluation: A Systematic Review of Methods. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 14(4), 2. Retrieved September 2022 from http://www.castore.ca/Information/Attachments/PESTEL%20analysis%20-%20Gillespie.pdf)

Loizia P, Voukkali I, Zorpas AA, Pedreno JN, Chatziparaskeva G, Inglezakis VJ, Vardopoulos I, Doula M (2021) Measuring the level of environmental performance in insular areas, through key performed indicators, in the framework of waste strategy development. Sci Total Environ 753:141974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141974

Srdjevic Z, Bajcetic R, Srdjevic B (2012) Identifying the criteria set for multicriteria decision making based on SWOT/PESTLE analysis: a case study of reconstructing a water intake structure. Water Resour Manage 26(12):3379–3393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-012-0077-2

Fernandes JP (2019) Developing viable, adjustable strategies for planning and management—A methodological approach. Land Use Policy 82:563–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.12.044

Hatvani N, van den Oever MJA, Mateffy K, Koos A (2022) Bio-based Business Models: specific and general learnings from recent good practice cases in different business sectors. Bio-based and Applied Economics. https://doi.org/10.36253/bae-10820

Barth H, Ulvenblad PO, Ulvenblad P (2017) Towards a conceptual framework of sustainable business model innovation in the agri-food sector: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 9(9):1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091620

Bocken N (2019) Sustainable Business Models. In: Leal Filho W, Azeiteiro U, Azul AM, Brandli L, Özuyar P, Wall T (eds) Decent Work and Economic Growth. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham Book accessible at: Retrieved August 2024 from https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319958668#aboutBook

Joyce A, Paquin RL (2016) The triple layered business model canvas: a tool to design more sustainable business models. J Clean Prod 135:1474–1486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

De Lauwere C, Slegers M, Meeusen M (2022) The influence of behavioural factors and external conditions on Dutch farmers’ decision making in the transition towards circular agriculture. Land Use Policy 120:106253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106253

Dagevos H, De Lauwere C (2021) Circular business models and circular agriculture: perceptions and practices of Dutch farmers. Sustainability 13:1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031282

Vermunt DA, Wojtynia N, Hekkert MP, Van Dijk J, Verburg R, Verweij PA, Wassen M (January 2022) Runhaar H (2022) Five mechanisms blocking the transition towards ‘nature inclusive’ agriculture: A systematic analysis of Dutch dairy farming. Agric Syst 195:103280

Yanore L, Sok J, Oude Lansink A (2024) Farmers’ perceptions of obstacles to business development. EuroChoices 23(1):56–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12420

Yanore L (2023) Exploring the Decision Making of Dutch Dairy Farmers Under Policy Uncertainty. PhD thesis Wageningen University. 31 October 2023 https://doi.org/10.18174/637537

Stokstad E (2019) Nitrogen crisis threatens Dutch environment and – economy. Science 366:1180–1181. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.366.6470.1180

Läpple D, Kelley H (2013) Understanding the uptake of organic farming: accounting for heterogeneities among Irish farmers. Ecol Econ 88:11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.12.025

Siebrecht N (2020) Sustainable agriculture and its implementation gap – overcoming obstacles to implementation. Sustainability 12(9):3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093853

Rodriguez JM, Molnar JJ, Fazio RA, Sydnor E, Lowe MJ (2009) Barriers to the adoption of sustainable agriculture practices: Change agent perspectives. Renewable Agric Food Syst 24(1):60–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170508002421