Abstract

Eyelid dermatitis (ED) affects a cosmetically significant area and leads to patients’ distress. Despite ongoing and recent research efforts, ED remains a multidisciplinary problem that needs further characterization. We aimed to evaluate the atopic eyelid dermatitis (AED) frequency in ED patients and to perform their clinical profiling. PubMed databases were searched from 01.01.1980 till 01.02.2024 to PRISMA guidelines using a search strategy: (eyelid OR periorbital OR periocular) AND (dermatitis or eczema). Studies with patch-tested ED patients were included. Proportional meta-analysis was performed using JBI SUMARI software. We included 65 studies across Europe, North America, Asia and Australia, with a total of 21,793 patch-tested ED patients. AED was reported in 27.5% (95% CI 0.177, 0.384) of patch-tested ED patients. Isolated ED was noted in 51.6% (95% CI 0.408, 0.623) of 8453 ED patients with reported lesion distribution, including 430 patients with isolated AED. Our meta-analysis demonstrated that the AED frequency in patch-tested ED patients exceeded the previous estimate of 10%. Isolated AED was noted in adult patients, attending contact allergy clinics. Future studies are needed to elucidate the global prevalence and natural history of isolated AED in adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eyelid dermatitis (ED) (Fig. 1) affects the periorbital skin1. Although ED has been a focus of large multi-center studies2,3,4,5,6,7, many aspects of ED, and particularly atopic eyelid dermatitis (AED), are only partially understood, highlighting important clinical needs and gaps of knowledge (Table 1).

Clinical presentations in patients with atopic eyelid dermatitis. Legend: The representative images of three patients with adult-onset atopic eyelid dermatitis (AED) (Patients 1–3), who are under care at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology (Head—Prof. Olga Olisova), I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University: patient 1 (A,D,H), aged 32 (an AED onset at 30 years), patient 2 (B,E,I), aged 37 (an AED onset at 37 years), patient 3, (C,F,J) aged 31 (an AED onset at 21 years). Facial skin imaging was carried out using the AI face recognition technology, 8-spectrum imaging technology and deep quantitative analysis by Capricorn Intelligent Imager ZMLH01 (Beijing Sincoheren S&T Development, Beijing, China). The high-definition images were acquired in a negatively polarized UV light (365 nm, A-F), white light (RGB, range 420–620 nm, H-J). AED patients presented with symmetrical, scaly erythematous periorbital areas with a hyperpigmentation and a lichenification, particularly pronounced at the medial aspects of the upper and lower eyelids. Informed consents from the AED patients for a publication of these images were obtained.

Importantly, eyelids are a visible and cosmetically significant area8, which is crucial for social interactions. Conditions affecting the face, especially the eye area, may contribute to a patient’s distress and social disadaptation8. For example, the impact on patients’ psychological well-being in AED is thought to be considerable9, and patient’s quality of life improves with skincare10 and topical treatment. However, the ED burden needs to be better characterized as the existing dermatological QoL instruments may only partially apply to ED. Currently, there is a need for evidence-based guidelines for the ED treatment because skin symptoms, their duration, resistance to topical treatment and severe disease burden may require special considerations in treatment decision-making in ED patients.

The eyelids are characterized by thin skin11 with fewer stratum corneum cell layers12, low surface lipid content13, and high drug permeability14. A close proximity of eyelids to ocular surface immunity15,16 creates a unique eye microenvironment that can be disturbed in skin conditions, affecting eyelids. For example, AD patients with comorbid ocular surface disease were shown to have decreased goblet cell density17,18, increased mucin (MUC5AC) production19, and elevated concentrations of proinflammatory mediators (histamine, LTB4)20 and cytokines (TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-5)21 in the tear fluid, thus opening the possibility of the biomarker development in the tear fluid in ED patients. These anatomical features, an immunological microenvironment, together with an exposure to allergens/irritants and chronic rubbing, may contribute to ED in predisposed individuals.

In clinical practice, ED may present a difficult challenge in a differential diagnosis with ED of various aetiology.22 In many cases, the ED etiology is difficult to establish23. Given a persistent course, frequent comorbidities and a broad differential diagnosis, ED is a multidisciplinary clinical problem, which is of interest for dermatologists, allergists, and ophthalmologists, justifying the set-up of multidisciplinary clinics for ED patients as implemented in some specialized centers.

In AED, ocular/periorbital changes (e.g. recurrent conjunctivitis, Dennie-Morgan infraorbital fold, keratoconus, anterior subcapsular cataracts and orbital darkening) were included in the 1980 Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria (H&R)24 but not in the U.K. Working Party’s diagnostic criteria (UKWP) for AD25, which may lead to an underdiagnosis of isolated AED. AED may last up to 10 years or longer26. Patients may repeatedly use topical corticosteroids (CS) around the eyes, with a limited effect27. AED may co-occur with common atopic diseases3 or ocular comorbidities, including allergic conjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, and keratoconus28. Known as a localized AD clinical phenotype, AED can be the only clinical manifestation in AD patients. The global prevalence of AED is unknown, although regional variations are likely to occur.

We hypothesized that AED may have phenotypic differences from ED in general. Here, we aimed (1) to carry out clinical profiling of ED patients, in general; (2) to systematically evaluate the AED frequency in patch-tested ED patients and (3) to carry out clinical profiling of adult AED patients. For this analysis, we focused on a patch-tested ED population due to two important considerations. Firstly, AED patients are often referred to contact allergy clinics and may not be under care as AD patients in specialized departments29. Secondly, using ‘flexural eczema’ as an inclusion criterion in epidemiological studies of AD may miss patients with isolated AED. This work will raise the awareness of medical professionals of an ED burden, its broad differential diagnosis, and may prompt further clinical and mechanistic studies in ED, particularly in AED.

Results

Study design

In total, 65 studies, published between 1986 and 2024, were included (Table S2)2,3,4,5,6,7,23,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85. In selected studies, there were 21,793 patch-tested ED patients. There were 25 large studies with 100 ED patients or more, ranging from 10065 to 4779 patients6 per study.

There were 12 prospective and 31 retrospective studies, with the remaining studies with an unspecified design (Table S2). Thirteen studies were multi-centered. Most studies were cross‐sectional (Table S2) and four studies were longitudinal20,34,41,58, with the follow-up period from 3 to 120 months in the study by Rapaport & Rapaport27, a follow-up of 12 weeks or longer in the study by Hong and colleagues41, the observation period of 60 days in the interventional study by Katsarou and colleagues58 and an unspecified follow-up period in the study by Ornek and coworkers34.

Setting

The studies were conducted various clinical settings, including dermatology or ophthalmology departments at the hospitals30,32,41,44,75, universities23,33,35,36,39,43,47,50,51,52,53,56,57,59,62,66,68,71,73,76,78, or institutes48,67, contact allergy clinics at the medical centers31,40, and a private practice39,44. Four large studies were conducted at 153 research centers of the German Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK)2,5,6,38. A large retrospective study of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG)4 collected data from 13 sites across the US and Canada. A large prospective study was carried out by the members of Dermato-Allergology Group of the French Society of Dermatology in 14 centers across France7 whereas another large multi-center study—by 12 SIDEV-GIRDCA research centers in Italy3. Selected studies were carried out across Europe, North America, Asia and Australia.

Study population

In 47 studies with gender reporting, there were 17,309 women, with the pooled proportion of 82.7% [95% CI 0.795; 0.856] (Fig. 2A). There was no difference in the racial distribution between ED patients and a general patch-tested patient population53 and no association between skin phototype and any specific diagnosis in ED patients3.

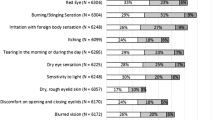

(A-Q) Forest plots for demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with eyelid dermatitis. Legend: The proportional meta-analyses [random-effects] were carried out for female patients (A) and patients aged 40 years or older (B) in the studies including the patients with eyelid dermatitis. The proportion of atopic eyelid dermatitis in the studies with patients with eyelid dermatitis (C) was estimated at 27.5% (95% CI 0.177, 0.384). The differential diagnosis of eyelid dermatitis includes eyelid allergic contact dermatitis (D), seborrheic dermatitis (E), psoriasis (F), and irritant contact dermatitis (G). H–N represent proportional meta-analyses for contact sensitizations to nickel (positive patch tests and clinically relevant reactions), gold, thimerosal, neomycin, and corticosteroids (budesonide and toxicortol), respectively. Clinically, the proportion of isolated eyelid dermatitis (O) of 8453 ED patients was 51.6% [95% CI 0.408, 0.623] whereas the proportion of isolated atopic eyelid dermatitis (P) of the patients with atopic dermatitis with an eyelid involvement was 26.9% [95% CI 0.117, 0.449].

In 13 studies, 9470 ED patients were aged 40 years or older, with the pooled proportion of 65.2% [95% CI 0.568; 0.731] (Fig. 2B). Isolated ED was more common in patients aged 30–70 years53.

Nethercott and colleagues32 noted that AED patients were younger than patients with ACD, ICD or other dermatoses. In the study by Svensson and Möller23, AED patients had a mean age of 42.2 years compared to that of 50.2 years (19–83) in ED patients. Of interest, 5/15 AED patients with previous or present flexural dermatitis had a mean age of 30 years23. As reported by Besra and coworkers67, AED patients were aged 28.7 ± 17.3. In the study by Hong and coworkers, 94.5% of 127 AED patients were under 30 years old66.

AED frequency

AED was reported in 27.5% [95% CI 0.177, 0.384] of ED patients across 29 studies (Fig. 2C). In two largest retrospective studies, AED was reported in 16.6% of 4779 patients6 and 13.4% of 3955 patients4. AD was more frequent in ED patients (including ED only4) than non-ED patients4,32, however, this was not confirmed in other studies53,71.

AED duration

ED duration can vary from a few weeks to several years3,7,40,75. The mean ED duration was 31.4 months (1–360 months) in a French prospective multicenter study (n = 264)7, which was in keeping with that of 29.5 months (1–180 months) in a retrospective single-centered study from Turkey (n = 60)75.

According to Bosco and coworkers71, 73.3% (140/191) of ED patients had a chronic/chronic recurring course (> 2 months). Assier and colleagues7 reported a chronic ED in 26.9% (71/264) cases.

Long-lasting AED (> 6 months) was noted in 69.1% (41/60) of patients by Ayala and colleagues3. In a follow-up by Ornek and coworkers75, 80% of AED patients had a prolonged disease. In the study by Hong and coauthors66, 26.3% of 80 AED patients had a relapse during a follow-up.

Risk factors

Feser and colleagues2 identified female gender, age ≥ 40 years and atopic skin diathesis as ED risk factors and a past history of AD was more frequent in ED patients compared to all patch-tested patients in Erlangen. In the prospective study of 447 ED patients3, a stepwise logistic regression model suggested a disease onset over 6 months before the examination [OR 4.9 [95% CI 1.8–13.9] and a personal history of atopy [26.9 [95% CI 11.0–65.4]] as the main AED risk factors.

Lesion distribution

In 26 studies, 51.6% [95% CI 0.408, 0.623] of 8453 ED patients presented with an eyelid involvement only, including in total 430 patients with isolated AED (Fig. 2O,P). Of 33 adult-onset AED patients, 14 had isolated AED, 12 AED with facial dermatitis and seven patients—AED with an involvement on other body sites42.

The lesional distribution in ED patients is of great clinical interest but the number of studies for each localization (face, head/neck, hands and other body parts) did not allow for meta-analyses. There is limited data on the distribution of eczematous lesions on the eyelids in patch-tested ED patients. In the study by Ayala and coworkers3, all patients with four eyelid involvement had ED only. In the French prospective study,7 four eyelids were involved in 185/238 patch-tested ED patients, upper eyelids—in 47/238, lower eyelids in 18/238 and unilateral involvement in four patients only. Crouse and coworkers76 reported that there were five AD patients out of 18 ED patients with a bilateral eyelid involvement. Whereas, ACD was diagnosed in patients with unilateral ED76, bilateral76 or four-eyelid involvement3,76. Notably, drug-induced ACD was noted to affect lower eyelids67. Additionally, Dennie‐Morgan fold was reported in 18.2% (8/44) of ED patients67.

Comorbidities

Atopic diseases

A history of atopy (defined as a personal or family history of eczema, asthma, or hay fever with or without positive prick tests to aeroallergens) in ED patients was reported in up to 50% of ED patients37. Ayala and colleagues reported a personal history of atopy in 80% of 55 AED patients3. In the study by Bosco and coworkers71, there was no difference in concomitant atopy between ED and non-ED.

Ocular diseases

Ocular symptoms were common in ED patients. Temesvári and coworkers57 reported that 30.4% of 401 ED patients had ocular symptoms, including chronic conjunctivitis (119/151 patients), blepharoconjunctivitis (31/151 patients) and corneal ulcus (1 patient). Assier and colleagues7 found conjunctivitis in 74 of 264 ED patients. Ocular symptoms were noted in 24.73% of 93 ED patients by Rojo-España and coworkers29.

Allergic contact dermatitis

In the meta-analysis of 38 selected studies, ACD was reported with a pooled proportion of 57.8% [0.477; 0.677] of 18,155 patch-tested ED patients, being the most common diagnosis in ED patients (Fig. 2D). Despite not being the focus of this study, these data provide important insights into relevant contact allergens in ED patients.

The most frequent contact allergens in ED patients were metals, fragrances and preservatives (Tables S3A-C). Nickel sulfate was the leading contact allergen in 23.2% (95% CI 0.167; 0.303) of 14,273 ED patients (Fig. 2H), with a wide variation in its clinical relevance ( Fig. 2I). The data on contact sensitization to nickel sulfate in ED patients compared to non-ED patients is conflicting (Table S5)7,37,49,61. Gold sensitization was noted in 13.5% [95% CI 0.037; 0.273] of 1845 ED patients (Fig. 2J) and was more frequent in ED than non-ED patients in the study by Warshaw and colleagues.4

Herbst and colleagues5 noted a downward trend in contact sensitization to fragrances over time. Importantly, contact sensitization to fragrances may occur by direct contact or through airborne exposure7. There was an upward trend in contact sensitization to MI/MCI after 2013 due to a global outbreak4,7,71. ED patients had more frequently positive patch tests to Kanthon CG than those without ED34. In the study by Bosco and colleagues71, MCI/MI sensitization was significantly more frequent in ED patients with an eyelid involvement only compared to ED patients with associated dermatitis at other body areas, highlighting an exclusive palpebral involvement for MI/MCI contact allergy. The cumulative frequency of contact sensitization to thiomersal in ED patients was estimated at 6.2% [0.046; 0.080] (Fig. 2K), although this may be of past clinical relevance due to thimerosal-containing vaccines. In the study by Feser and coauthors2, ophthalmic therapeutics were clinically relevant in older ED patients compared with all patch-tested patients. Contact sensitization to neomycin was reported in 1.43% [95% CI 0.053; 0.266] of ED patients (Fig. 2L). By contrast, occupational cases were less frequent in ED patients than non-ED patients6.

Given multiple contact sensitizations in some patients, the relevance of contact sensitizations to certain allergens may well have been overestimated32. Clinical relevance was significantly higher in ED patients with multiple contact sensitizations than in monosensitized individuals29.

Atopic eyelid dermatitis with superimposed allergic contact dermatitis

There were 164 AED patients with superimposed ACD in nine studies (Fig. 2Q). In the study by Ochenfels and colleagues38, positive patch tests were found in every third AD patient. Contact sensitizations in AED patients were reported only by Ayala and coauthors3: nickel sulfate—29.6%, Dermatophagoides mix—44.4%, perfume mix—11.1% and cobalt chloride—11.1%. However, the clinical relevance of these sensitizations in AED needs further research.

Diagnostic work-up

Questionnaires

Standardized questionnaires were used in all multicenter studies3,5,6,7,38. The Erlangen Atopy questionnaire and the MOAHLFA (male, occupational dermatoses, atopic eczema, hand dermatitis, leg dermatitis, facial dermatitis, age ≥ 40 years) was used in ED patients in Erlangen and IDVK (excluding Erlangen) cohorts2. Ocular questionnaires [e.g. Visual Functioning Questionnaire 25 (VQF-25)] or standardized measurement instruments (e.g. Total Ocular Symptom Score (TOSS) or Ocular Surface Disease Index) were not used in the selected studies.

Patch testing

From 1986 to 2024, 21,793 patch-tested ED patients across 65 studies were patch tested to exclude suspected ACD, using NACDG panel4,32,40,53,76, European standard series7,32,37,41,42, standard ICDRG panel23, and country-specific baseline series2,3,29,38,61,75. According to Amin and Belsito53, most culprit contact allergens in ED patients were not included in standardized panels in the US.

In the selected studies, specialized series included fragrance, ophthalmic drug, eyelid series, preservative, antiseptic, facial series, medicament series, and parfum series. The use of specific eyelid/ophthalmic patch testing series yielded positive results in 4/264 ED patients in the study by Assier and coworkers7, and in 9/133 ED patients as reported by Temesváry and colleagues57.

Importantly, positive reactions were found in patients tested with their own products, which included facial moisturizers, cosmetics, ophthalmic medications, eye drops, nail vanishes and glue products. Assier and coworkers7 reported that 19% (16/82) of the allergic patients were only identified by testing with their personal products. In the study by Katz and colleagues40, 11 of 32 patients, who reacted to their own products, had negative patch tests with standard series. Rojo-Espana and colleagues29 carried out open tests on the periorbital area in 36/93 patients, using the products as patches on one eyelid or as drops in one eye. In a French study28, repeated open application test or a use test was positive in 4/16 patients with negative patch testing.

Positive patch tests to dust mite mix were reported in 32 of 58 ED patients in Guin’s clinical practice45 and in 44.4% of AED patients in the study by Ayala and coworkers3. Pónyai and coworkers56 reported positive atopy patch tests to house dust mites in six AD patients with eyelid symptoms.

Allergy testing with aeroallergens

As reported by Ornek and colleagues75, in 15% (9/60) ED patients with positive prick tests, the most prevalent allergens were house dust mites (HDM) (D. pterynissinus—11.6% (7/60); D. farina—11.6% (7/60), grass mix—5% (3/60), and cat dander—3.3% (2/60). In four studies7,42,45,49, prick tests with aeroallergens were performed without reporting the results. Component-resolved diagnosis has not been used in selected studies, therefore, the molecular patterns of HDM sensitization in AED patients remains to be established.

Microbiome studies

There were no microbiome data in AED patients in the selected studies.

AED clinical diagnosis

Several diagnostic criteria were used across selected studies, including the H&R diagnostic criteria29,34,56,61 and the UKWP criteria7. Some authors relied on a personal or family history of atopy, personal history of eczema in childhood/early adulthood, lesion distribution typical for AD with42 or without positive prick testing to aeroallergens45,71, but lacking contact allergy. Others diagnosed AD based on present or past history of flexural or popliteal eczema23,42. Feser and colleagues2 used the Erlanger Atopy Score (a mean score ≥ 12.5 points for AED patients). Svensson and Möller23 used their own scoring system of patient’s history and clinical data.

Differential diagnosis

The most common cause of ED was ACD (Table 2). Common differential diagnoses in ED patients include ICD (Fig. 2G), seborrheic dermatitis (Fig. 2E) and airborne dermatitis. Warshaw and colleagues4 reported ACD to be more common in ED patients with or without a head/neck involvement, possibly due to allergen spreading to the adjacent areas. Rare causes of ED were psoriasis (Fig. 2F) and rosacea. Guin49 reported tinea involving the eyelids (2 patients) and viral epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (1 patient) as rare ED causes. There were three patients with periorbital discoid lupus erythematosus57,75, one patient—with progressive systemic sclerosis57 and one patient—with mucosal pemphigoid2.

Treatment

Rappaport and Rappaport27 observed 67 patch-tested AED patients, who chronically used topical and/or systemic CS. The addiction to topical CS may occur within two months of continuous use. In AED patients, the duration of the previous CS use was 3–480 months, mostly 1–2 years. Burning was noted in 43%, telangiectasia in 31%, and skin atrophy—in 26% of AED patients. Noteworthy, contact sensitization to budesonide was reported in 1.5% [0.007; 0.026] of 1795 ED patients (Fig. 2M) and to tixocortol—in 1.4% [0.005; 0.025] of 1840 patch-tested ED patients (Fig. 2N). On stopping the CS use, distant eczematous rashes (often on antecubital areas, or the legs or upper chest) occurred in 20/67 AED patients. Occasionally, UVB phototherapy was used upon a CS withdrawal. Clearing, without AED flare-ups for 4–6 weeks, was achieved in 2–30 months of a CS discontinuation27.

Discussion

Our main finding was the AED frequency of 27.5% (95% CI0.177, 0.384) in patch-tested ED patients, exceeding the previous estimate of over 10%22. Importantly, isolated AED, as a distinct localized AD phenotype in adults, was reported in 430 AD patients, although its frequency in adult AD patients remains unknown. Patients with isolated AED may be more likely to attend contact allergy clinics and, therefore, may not have been included in large AD cohorts. Flexural AD is frequently included as diagnostic criterion in epidemiological studies86, and thus may overlook patients with isolated AED. From a global perspective, published studies with AED patients were mostly carried out in Europe and the US, were underrepresented in Asia and Australia, and were lacking in South America and Africa. Future studies are needed to elucidate the frequency of isolated AED in adult AD patients, taking into account a global variation in AD phenotypic presentations across races and ethnicities87.

High proportion of ED patients aged 40 years or older may reflect age-dependent variations in stratum corneum thickness and hydration in the eyelid area. Limited evidence suggests that AED patients may be younger than ED patients. This is in keeping with a recent prospective study88, a meta-analysis89 and our clinical experience suggesting higher AED likelihood in children and young adults. Future studies into gender- and age-related differences in eyelid stratum corneum morphology and function in ED/AED patients may provide an explanation for their demographic characteristics.

An ED duration may exceed 6 months in some patients3,7,27. This warrants further studies into an AED natural history. Published AED case reports26 suggest that AED may last up to 10 years or longer, thus raising the questions as to which factors (the country of residence, airborne pollution, climatic differences, allergen sensitization, genetic and socioeconomic factors, etc.) may underlie the AED persistence in adults. It remains unclear whether chronic periorbital changes (chronic lichenification, Dennie-Morgan infraorbital fold(s)) in AED can be prevented.

Clinical scoring of AED severity has been proposed90. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) can be measured on the eyelids, using closed-chamber devices with goggle-adaptors90,91, although eyelid TEWL can be affected by tear evaporation. Comorbidities may increase the AED burden. In a meta-analysis28, conjunctivitis was reported in 31.7% (95% CI 27.7–35.9) of AD patients, although the data for AD phenotypes (including AED) was limited. In a prospective study17, moderate-to-severe ocular surface disease was significantly more frequent in patients with AED or AD facial involvement in the past year. Future studies into ocular surface disease in AED patients may help elucidate whether AED patients should have a baseline ophthalmic examination. Until then, a referral to an eye care specialist is warranted for patients with conjunctival scarring or swelling, pain, watery discharge, blepharitis, dryness, irritation and light sensitivity or vision problems92 or symptomatic AD patients, whose ocular symptoms do not improve within 2 weeks93. However, some authors advocate a baseline ophthalmological examination for at-risk individuals, including ED patients92.

The link between ACD and AD has been a subject of controversy and intense research94. Our meta-analysis suggested that superimposed ACD may occur in AED patients. In our analysis, ED patients were frequently sensitized to metals, fragrances and preservatives which is in keeping with previous studies of eyelid ACD64,95, and general patch-tested population96. Some contact allergens, however, were more frequent in ED patients4,32,53,71, particularly, with a predilection to an exclusive eyelid involvement for MI/MCI71. An individualized approach with baseline and specialized panels and, importantly, patient’s own products2, related to patient’s occupational, personal care products and/or topical medications, can be useful in AED patients. Albeit being used by some authors29,97, patch testing or repeated open application test on eyelid(s) has to be further evaluated. A conjunctival challenge test was proposed for ED patients with conjunctival symptoms to topical ophthalmic drugs6.

In clinical practice, it may be difficult to distinguish isolated AED and ICD on clinical grounds or by using available diagnostic approaches (patch testing, repeated open application test). Skin testing with irritants and repeated open application tests may be helpful to diagnose ICD in healthy individuals but not in atopic patients as these two conditions may co-exist. Skin biopsy on the eyelid area is rarely used for differential diagnosis of ED in dermatological practice. In research, transcriptomic biomarkers by skin tape stripping have been successfully used for differential diagnosis of AD, psoriasis, ACD and ICD98,99 but not specifically on the eyelid area. It remains to be established whether transcriptomic biomarkers in the skin and the tear fluid can be used for differential diagnosis of AED and other skin conditions affecting the eyelid area.

Non-pharmacological options include allergen avoidance, including relevant contact allergens and aeroallergens if possible. Until further evidence, the avoidance of certain contact allergens is not warranted in all AED patients100. Some ED patients sensitized to gold sodium thiosulfate may benefit from a 2-to-3 month trial of gold jewelry avoidance to establish clinical relevance101. HDM avoidance was shown to be effective in reducing the AD severity due to the reduction of Der p 1 concentration in the domestic environment in a landmark UK-based double-blind controlled study102. In illustrative cases by Beltrani101, AED patients may benefit from HDM elimination measures, although this requires further research in larger cohorts. The use of artificial tears can be helpful.

A short trial with low-potency topical CS may be required. Unfortunately, AED patients may over-use topical CS, with CS dependency occurring within two months of a continuous use.27 A prolonged use of topical CS in the eyelid area is associated with the risk of increased intraocular pressure in at-risk individuals103. Contact allergy to CS (Fig. 2M) may occur in ED patients5,7,29,41,45,53,71,75,76 but its frequency in AED is currently unknown. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are preferred for the eyelid areas. The phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole can be used around eyes104. Narrowband UVB phototherapy should be used with caution for AED patients105, because keratinopathy was reported in an AED patient106. Allergen-specific immunotherapy has not been evaluated in AED patients with or without atopic comorbidities. The use of biological therapies (omalizumab and dupilumab) in AED patients is of clinical interest. Janus kinase inhibitors (Table 3) were shown to be effective in an ED patient107 and in AD patients with severe blepharitis108.

In our comprehensive analysis of 65 studies with adult ED patients, the strengths rely mostly on high-quality studies, including large multi-center studies2,3,4,5,6,7. and the use of patch testing in ED patients. However, our analysis revealed certain limitations. Firstly, the studies with ED patients were carried out with different objectives7, study designs and study populations, thus resulting in a high heterogeneity between the included studies which is common in the proportional meta-analyses in the prevalence studies109. Secondly, different AED criteria across the studies may not be equally sensitive to adult-onset AD or phenotypic differences in patients of various descent57. Furthermore, a referral bias to contact allergy clinics42 may have led to an ACD overrepresentation. Whereas, AED patients may have been under-reported due to a frequent recall bias for AD28. Most studies were carried out in the academic settings, thus reducing the generalizability of the results to the real-life clinical practice. Our inclusion criteria and the search period (1980–2024) did not include some large ED series without patch testing110. Nevertheless, we believe that our systematic review allowed us to glean important insights into ED/AED demographic and clinical features which can be useful for clinical practice.

Many unresolved questions related to AED clinical profiling remain. In the future, the AED disease burden requires a closer attention, particularly in AED patients with all skin types worldwide, given notable AD phenotypic differences in various geographical regions. Age-related differences in AED clinical presentations may provide further insights into adult-onset AED. An ongoing multicenter observational prospective PAUPIAD study (NCT04826744) in France will characterize a palpebral involvement in adult AD patients.

Much work needs to be done to further understand the genetic background, environmental factors (aeroallergens and pollutants) and gene-environmental interactions that may influence the AED development. Further research is needed on AED endotyping in adults based on allergen sensitizations, FLG mutations, microbiome and possibly by the transcriptome in the tear fluid and in the eyelid skin.

In conclusion, there is a need for an optimized diagnostic algorithm, better treatments and prevention strategies in AED patients. It remains to be seen whether patients with severe treatment-resistant AED may be eligible for topical (eg. JAK inhibitors, topical Syk inhibitor) or systemic biological agents (eg. omalizumab, dupilumab). In the future, precision medicine based on AED clinical profiling and endotyping, together with the AI use for digital eyelid images, may advance the AED management, thereby reducing patient’s disease burden, improving their outcome and preventing long-term sequelae.

Methods

PubMed/Medline database was searched from 1980, since the 1980 H&R diagnostic criteria24, till 1 September 2022, using a search strategy: ((eyelid OR periorbital OR periocular) AND (dermatitis or eczema)) in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Appendix 1, Figs. S1–S2)111. There were no language restrictions applied to the search strategy.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) the ED diagnosis; and (2) patch testing. The exclusion criteria were: (1) reviews/editorials/guidelines/correspondence; (2) abstracts, conference posters/oral presentations, (3) studies not in humans; 4) diagnoses other than ED (5) patients aged < 18 years old; (6) drug-related side-effects with an eyelid involvement; (7) unclassified ED and (8) dupilumab-associated ocular conditions in AD patients. The reference lists were screened for additional studies. Case reports with 1–3 cases were excluded.

Initial title and abstract screening and full-text reviews were carried out by three reviewers (EB, ES and AB) (Tables S2, S4). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved via consensus. The methodological quality of selected studies was assessed using Newcastle–Ottawa scale modified for AD cross-sectional studies (Tables S1)112. A proportional meta-analysis was carried out using JBI SUMARI software. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 statistic.

Data availability

All data used in the study are from publicly available sources that are listed in the tables and cited in the references. The tables and the study protocol and all datasets generated and analysed, including the search strategy, data extracted and quality assessment, are available in the Article and on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACD:

-

Allergic contact dermatitis

- AD:

-

Atopic dermatitis

- AED:

-

Atopic eyelid dermatitis

- CS:

-

Corticosteroids

- DKG:

-

German Contact Dermatitis Research Group

- ED:

-

Eyelid dermatitis

- FLG :

-

Filaggrin gene

- GIRDCA:

-

Gruppo Italiano Ricerca Dermatitida Contatto Ambientali

- HDM:

-

House dust mites

- H&R:

-

The 1980 Hanifin and Rajka criteria

- ICDRG:

-

International Contact Dermatitis Research Group

- IgE:

-

Immunoglobulin E

- IL-4:

-

Interleukin—4

- IL-5:

-

Interleukin—5

- IVDK:

-

Information Network of Departments of Dermatology

- LTB4:

-

Leukotriene B4

- MUC5AC:

-

Mucin—5AC

- NACDG:

-

North American Contact Dermatitis Group

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled study

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SIDAPA:

-

Italian Society of Allergological Dermatology

- TEWL:

-

Transepidermal water loss

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor—alpha

- UKWP:

-

UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria

References:

Beltrani, V. S. Eyelid dermatitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 1, 380–388 (2001).

Feser, A., Plaza, T., Vogelgsang, L. & Mahler, V. Periorbital dermatitis—a recalcitrant disease: Causes and differential diagnoses. Br. J. Dermatol. 159, 858–863 (2008).

Ayala, F. et al. Eyelid dermatitis: An evaluation of 447 patients. Am. J. Contact Dermat. 14, 69–74 (2003).

Warshaw, E. M. et al. Eyelid dermatitis in patients referred for patch testing: Retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1994–2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 84, 953–964 (2021).

Herbst, R. A., Uter, W., Pirker, C., Geier, J. & Frosch, P. J. Allergic and non-allergic periorbital dermatitis: Patch test results of the Information Network of the Departments of Dermatology during a 5-year period. Contact Dermat. 51, 13–19 (2004).

Landeck, L., John, S. M. & Geier, J. Periorbital dermatitis in 4779 patients—patch test results during a 10-year period. Contact Dermat. 70, 205–212 (2014).

Assier, H. et al. Is a specific eyelid patch test series useful? Results of a French prospective study. Contact Dermat. 79, 157–161 (2018).

Rumsey, N. & Harcourt, D. The Psychology of Appearance 1st edn. (Open University Press, New York, 2005).

Feser, A. & Mahler, V. Periorbital dermatitis: Causes, differential diagnoses and therapy. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 8, 159–165 (2010).

Bergera-Virassamynaik, S., Ardiet, N. & Sayag, M. Evaluation of the efficacy of an ecobiological dermo-cosmetic product to help manage and prevent relapses of eyelid atopic dermatitis. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 16, 677–686 (2023).

Meng, Y., Feng, L., Shan, J., Yuan, Z. & Jin, L. Application of high-frequency ultrasound to assess facial skin thickness in association with gender, age, and BMI in healthy adults. BMC Med. Imaging. 22, 113 (2022).

Ya-Xian, Z., Suetake, T. & Tagami, H. Number of cell layers of the stratum corneum in normal skin—relationship to the anatomical location on the body, age, sex and physical parameters. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 291, 555–559 (1999).

Pratchyapruit, W., Kikuchi, K., Gritiyarangasan, P., Aiba, S. & Tagami, H. Functional analyses of the eyelid skin constituting the most soft and smooth area on the face: Contribution of its remarkably large superficial corneocytes to effective water-holding capacity of the stratum corneum. Skin Res. Technol. 13, 169–175 (2007).

Emeriewen, K., Saleh, G., McAuley, W. & Cork, M. The permeability of eyelid skin to topically applied lidocaine. Investig. Ophthal. Visual Science. 59, 83 (2018).

Bielory, L. Allergic and immunologic disorders of the eye. Part I: Immunology of the eye. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 106, 805–816 (2000).

Foulsham, W., Coco, G., Amouzegar, A., Chauhan, S. K. & Dana, R. When clarity is crucial: Regulating ocular surface immunity. Trends Immunol. 39, 288–301 (2018).

Achten, R. E. et al. Ocular surface disease is common in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 52, 801–805 (2022).

Nelson, J. D. & Wright, J. C. Conjunctival goblet cell densities in ocular surface disease. Arch. Ophthalmol. 102, 1049–1051 (1984).

Dogru, M. et al. Atopic ocular surface disease: Implications on tear function and ocular surface mucins. Cornea 24, S18–S23 (2005).

Uchio, E., Miyakawa, K., Ikezawa, Z. & Ohno, S. Systemic and local immunological features of atopic dermatitis patients with ocular complications. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 82, 82–87 (1998).

Wakamatsu, T. H. et al. Evaluation of lipid oxidative stress status and inflammation in atopic ocular surface disease. Mol. Vis. 16, 2465–2475 (2010).

Wolf, R., Orion, E. & Tüzün, Y. Periorbital (eyelid) dermatides. Clin. Dermatol. 32, 131–140 (2014).

Svensson, A. & Möller, H. Eyelid dermatitis the role of atopy and contact allergy. Contact Dermat. 15, 178–182 (1986).

Hanifin, J. & Rajka, G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovener (Stockholm). 92, 44–47 (1980).

Williams, H. C., Burney, P. G., Strachan, D. & Hay, R. J. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for atopic dermatitis. II. Observer variation of clinical diagnosis and signs of atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 131, 397–405 (1994).

Rikkers, S. M. et al. Topical tacrolimus treatment of atopic eyelid disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 135, 297–302 (2003).

Rapaport, M. J. & Rapaport, V. Eyelid dermatitis to red face syndrome to cure: Clinical experience in 100 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 41, 435–442 (1999).

Ravn, N. H. et al. Bidirectional association between atopic dermatitis, conjunctivitis, and other ocular surface diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 85, 453–446 (2021).

Rojo-España, R. et al. Epidemiological study of periocular dermatitis in a specialised hospital department. Iran J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 10, 195–205 (2011).

De Groot, A. C. Contact allergy to cosmetics: Causative ingredients. Contact Dermat. 17, 26–34 (1987).

Goh, C. L. Eczema of the face, scalp and neck: An epidemiological comparison by site. J. Dermatol. 16, 223–226 (1989).

Nethercott, J. R., Nield, G. & Holness, D. L. A review of 79 cases of eyelid dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 21, 223–230 (1989).

Gailhoper, G. & Ludvan, M. ‘Beta-blockers’: Sensitizers in periorbital allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 23, 262 (1990).

Valsecchi, R., Imberti, G., Martino, D. & Cainelli, T. Eyelid dermatitis an evaluation of 150 patients. Contact Dermat. 27, 143–147 (1992).

Wolf, R. & Perluk, H. Failure of routine patch test results to detect eyelid dermatitis. Cutis 49, 133–134 (1992).

Katayama, I., Koyano, T. & Nishioka, K. Prevalence of eyelid dermatitis in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Int. J. Dermatol. 33, 421–424 (1994).

Shah, M., Lewis, F. M. & Gawkrodger, D. J. Facial dermatitis and eyelid dermatitis a comparison of patch test results and final diagnoses. Contact Dermat. 34, 140–141 (1996).

Ockenfels, H. M., Seemann, U. & Goos, M. Contact allergy in patients with periorbital eczema: An analysis of allergens. Dermatology. 195, 119–124 (1997).

De Groot, A. C., van Ginkel, C. J., Bruynzeel, D. P., Smeenk, G. & Conemans, J. M. Contact allergy to eyedrops containing beta-blockers. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 142, 1034–1036 (1998).

Katz, A. S. & Sherertx, E. F. Facial dermatitis: Patch test results and final diagnoses. Am. J. Contact Dermat. 10, 153–156 (1999).

Cooper, S. M. & Shaw, S. Eyelid dermatitis: An evaluation of 232 patch test patients over 5 years. Contact Dermat. 42, 291–293 (2000).

Bannister, M. J. & Freeman, S. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Austral. J. Dermatol. 41, 225–228 (2000).

Ehrlich, A. & Belsito, D. V. Allergic contact dermatitis to gold. Cutis. 65, 323–326 (2000).

Delaney, Y. M. et al. Periorbital dermatitis as a side effect of topical dorzolamide. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 86, 378–380 (2002).

Guin, J. Eyelid dermatitis: Experience in 203 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 47, 755–765 (2002).

Goossens, A. Contact allergic reactions on the eyes and eyelids. Bull. Soc. Belge Ophtalmol. 292, 11–17 (2004).

Corazza, M., Masieri, L. T. & Virgili, A. Doubtful value of patch testing for suspected contact allergy to ophthalmic products. Acta Derm. Venereol. 85, 70–71 (2004).

Dirschka, T. & Tronnier, H. Periokuläre dermatitis. JDDG 2, 274–278 (2004).

Guin, J. D. Eyelid dermatitis: A report of 215 patients. Contact Dermat. 50, 87–90 (2004).

Borch, J. E., Elmquist, J. S., Bindslev-Jensen, C. & Andersen, K. E. Phenylephrine and acute periorbital dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 53, 298–299 (2005).

Corazza, M. & Virgili, A. Allergic contact dermatitis from ophthalmic products: Can pre-treatment with sodium lauryl sulfate increase patch test sensitivity?. Contact Dermat. 52, 239–241 (2005).

Slodownik, D. & Ingber, A. Thimerosal—is it really irrelevant?. Contact Dermat. 53, 324–326 (2005).

Amin, K. A. & Belsito, D. V. The aetiology of eyelid dermatitis: A 10-year retrospective analysis. Contact Dermat. 55, 280–285 (2006).

Foti, C. et al. Allergia da contatto ai component di una “serie integrative profumi” in pazienti con dermatite eczematosa. Ann. Ital. Dermatol. Allergol. 61, 12–17 (2007).

Nino, M., Balato, N., Ayala, F. & Ayala, F. Dermatite allergica da contatto delle palpebre da topici oftalmici. Il ruolo dei b-bloccanti: problem di diagnosi e gestione. Ann. Ital. Dermatol. Allergol. 61, 18–22 (2007).

Pónyai, G. et al. Contact and aeroallergens in adulthood atopic dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 22, 1346–1355 (2008).

Temesvári, E. et al. Periocular dermatitis: A report of 401 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 23, 124–128 (2009).

Katsarou, A. et al. Tacrolimus ointment 01% in the treatment of allergic contact eyelid dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 23, 382–387 (2009).

Carlsen, B. C., Andersen, K. E., Menné, T. & Johansen, J. D. Sites of dermatitis in a patch test population: Hand dermatitis is associated with polysensitization. Contact Dermat. 61, 22–30 (2009).

Landeck, L., Schalock, P. C., Baden, L. A. & Gonzalez, E. Periorbital contact sensitization. Am J Ophthalmol. 150, 366–370 (2010).

Zeppa, L., Bellini, V. & Lisi, P. Atopic dermatitis in adults. Dermatitis. 22, 40–46 (2011).

Du-Thanh, A., Siret-Alatrista, A., Guillot, B. & Raison-Peyron, N. Eyelid contact dermatitis due to an unsuspected eye make-up remover. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 25, 112–113 (2011).

Morris, S., Barlow, R., Selva, D. & Malhotra, R. Allergic contact dermatitis: A case series and review for the ophthalmologist. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 95, 903–908 (2011).

Herro, E. M., Elsaie, M. L., Nijhawan, R. I. & Jacob, S. E. Recommendations for a screening series for allergic contact eyelid dermatitis. Dermatitis. 23, 17–21 (2012).

Wenk, K. S. & Ehrlich, A. Fragrance series testing in eyelid dermatitis. Dermatitis. 23, 22–26 (2012).

Hong, K. C., Kim, S. H., Kim, M. S., Lee, U. H. & Park, H. S. A study of the causative diseases for eyelid dermatitis. Korean J Dermatol. 51, 579–585 (2013).

Besra, L., Jaisankar, T. J., Thappa, D. M., Malathi, M. & Kumari, R. Spectrum of periorbital dermatoses in South Indian population. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 79, 399–407 (2013).

Madsen, J. T. & Andersen, K. E. Phenylephrine is a frequent cause of periorbital allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 73, 49–67 (2015).

Gupta, M., Mahajan, V. K., Mehta, K. S. & Chauhan, P. S. Hair dye dermatitis and p-phenylenediamine contact sensitivity: A preliminary report. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 6, 241–246 (2015).

Oh, J. E., Lee, H. J., Choi, Y. W., Choi, H. Y. & Byun, J. Y. Metal allergy in eyelid dermatitis and the evaluation of metal contents in eye shadows. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 30, 1518–1521 (2016).

Bosco, L., Schena, D. & Girolomoni, G. The aetiology of eyelid dermatitis in a series of 191 patients. Clinical Dermatol. 4, 1–7 (2016).

Schwensen, J. F. et al. The epidemic of methylisothiazolinone: A European prospective study. Contact Dermat. 76, 272–279 (2017).

Chisholm, S. A. M., Couch, S. M. & Custer, P. L. Etiology and management of allergic eyelid dermatitis. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 33, 248–250 (2017).

Nečas, M. & Dastychová, E. Periorbital allergic contact dermatitis—the most common allergens in the Czech Republic. Int. J. Ophthalmol. Clin. Res. 4, 074 (2017).

Ornek, S. A. et al. Periorbital dermatitis: The role of type 1 and type 4 hypersensitivity as contributing factors. Austin J Allergy. 4, 1028 (2017).

Crouse, L., Ziemer, C. & Lugo-Somolinos, A. Trends in eyelid dermatitis. Dermatitis 29, 96–97 (2018).

Gilissen, L., De Decker, L., Hulshagen, T. & Goossens, A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical ophthalmic medications: Keep an eye on it!. Contact Dermat. 80, 291–297 (2019).

Pandit, S. A. & Glass, L. R. D. Non-glaucoma periocular allergic, atopic, and irritant dermatitis at an academic institution: A retrospective review. Orbit 38, 112–118 (2018).

Borghi, A. et al. Eyelid dermatitis and contact sensitization to nickel: Results from an Italian multi-centric observational study. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 19, 38–45 (2019).

Huang, C. X., Yiannias, J. A., Killian, J. M. & Shen, J. F. Seven common allergen groups causing eyelid dermatitis: Education and avoidance strategies. Clin. Ophthalmol. 15, 1477–1490 (2021).

Alves, P. B., Figueiredo, A. C., Codeço, C., Regateiro, F. S. & Gonçalo, M. A closer look at allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical ophthalmic medications. Contact Dermat. 87, 331–335 (2022).

Özkaya, E., Keskinkaya, Z. & Kobaner, G. B. Tobramycin and antiglaucoma agents as increasing culprits of periorbital allergic contact dermatitis from topical ophthalmic medications: A 24-year study from Turkey. Contact Dermat. 89, 37–45 (2023).

Hafner, M. F. S., Elia, V. C., Lazzarini, R. & Duarte, I. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with eyelid eczema attended at a referral service from 2004 to 2018. An Bras Dermatol. 98, 84–86 (2023).

Yazdanparast, T. et al. Contact allergens responsible for eyelid dermatitis in adults. J. Dermatol. 51, 691–695 (2024).

Stingeni, L. et al. Contact allergy to SIDAPA baseline series allergens in patients with eyelid dermatitis: An Italian multicentre study. Contact Dermat. 90, 479–485 (2024).

Sacotte, R. & Silverberg, J. I. Epidemiology of adult atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 36, 595–605 (2018).

Nomura, T., Wu, J., Kabashima, K. & Guttman-Yassky, E. Endophenotypic variations of atopic dermatitis by age, race, and ethnicity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 8, 1840–1852 (2020).

Chatrath, S. & Silverberg, J. I. Phenotypic differences of atopic dermatitis stratified by age. JAAD Int. 11, 1–7 (2022).

Yew, Y. W., Thyssen, J. P. & Silverberg, J. I. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J Am. Acad. Dermatol. 80, 390–401 (2019).

Asano-Kato, N. et al. Quantitative evaluation of atopic blepharitis by scoring of eyelid conditions and measuring the water content of the skin and evaporation from the eyelid surface. Cornea 20, 255–259 (2001).

Nuutinen, J., Harvima, I., Lahtinen, M.-R. & Lahtinen, T. Water loss through the lip, nail, eyelid skin, scalp skin and axillary skin measured with a closed-chamber evaporation principle. Br. J. Dermatol. 148, 823–842 (2003).

Shi, V. Y. et al. Practical management of ocular surface disease in patients with atopic dermatitis, with a focus on conjunctivitis: A review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 89, 309–315 (2023).

Thyssen, J. P. et al. Management of ocular manifestations of atopic dermatitis: A consensus meeting using a modified Delphi process. Acta Derm. Venereol. 100, adv00264 (2020).

Milam, E. C., Jacob, S. E. & Cohen, D. E. Contact dermatitis in the patient with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 7, 18–26 (2019).

Rietschel, R. L. et al. Common contact allergens associated with eyelid dermatitis: Data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2003–2004 study period. Dermatitis 18, 78–81 (2007).

Alinaghi, F., Bennike, N. H., Egeberg, A., Thyssen, J. P. & Johansen, J. D. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermat. 80, 77–85 (2019).

Schlotmann, K., Goerz, G., Straube, A. N. & Schürer, N. Y. In-loco-Epikutantestung bei Verdacht auf allergisches Lidekzem. Allergologie. 19, 103 (1996).

Sølberg, J. B. K. et al. The transcriptome of hand eczema assessed by tape stripping. Contact Dermat. 86, 71–79 (2022).

He, H. et al. Tape strips detect distinct immune and barrier profiles in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 147, 199–212 (2021).

Pootongkam, S. & Nedorost, S. Allergic contact dermatitis in atopic dermatitis. Curr. Treat. Opin. Allergy. 1, 329–336 (2014).

Tan, B. B., Weald, D., Strickland, I. & Friedmann, P. S. Double-blind controlled trial of effect of house dust-mite allergen avoidance on atopic dermatitis. Lancet 347, 15–18 (1996).

Beltrani, V. S. The role of house dust mites and other aeroallergens in atopic dermatitis. Clin. Dermatol. 21, 177–182 (2003).

Maeng, M., De Moraes, C. G., Winn, B. J. & Glass, L. R. D. Effect of topical periocular steroid use on intraocular pressure: A retrospective analysis. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 35, 465–468 (2019).

Lynde, C. W. et al. Optimal use of crisaborole in atopic dermatitis—an expert guidance document. Skin Ther. Lett. 16, 1S-12S (2021).

Prystowsky, J. H., Keen, M. S., Rabonowitz, A. D., Stevens, A. W. & DeLeo, V. A. Present status of eyelid phototherapy Clinical efficacy and transmittance of ultraviolet and visible radiation through human eyelids. J Am. Acad. Dermatol. 26, 607–613 (1992).

Komericki, P., Fellner, P., El-Shabrawi, Y. & Ardjomand, N. Keratopathy after ultraviolet B phototherapy. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 117, 300–302 (2005).

Peterson, D. & King, B. Remission of severe eyelid dermatitis with a topical Janus Kinase inhibitor. Dermatitis 32, e98–e99 (2021).

Dainichi, T., Kaku, Y., Izumi, M. & Kataoka, K. Successful treatment of severe blepharitis in a patient with atopic dermatitis by topical delgocitinib. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 46, 1102–1136 (2021).

Migliavaca, C. B. et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence: I(2) statistic and how to deal with heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 13, 363–367 (2022).

Kim, M., Jang, H. & Rho, S. Risk factors for periorbital dermatitis in patients using dorzolamide/timolol eye drops. Sci. Rep. 11, 17896 (2021).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Totté, J. E. E. et al. Prevalence and odds of Staphylococcus aureus carriage in atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 175, 687–695 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for editorial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Resources, Data curation, Writing—Original draft preparation. E.S.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. A.B.: Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing—Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

EB serves on the WAO Committee on Atopic Dermatitis, received honoraria for educational lectures from Novartis and Sanofi and research funding from GSK, outside the submitted work. EB provided pro bono consulting to Kimialys (France) outside the submitted work. EB received research funding from the British Skin Foundation (2009) for her research, outside the submitted work. ES received honoraria for lectures from Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd., as well as support for attending congresses from Galderma and Drs. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd. as a lecturer. AB is working on her PhD research project on atopic eyelid dermatitis supervised by ES and EB.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borzova, E., Snarskaya, E. & Bratkovskaya, A. Eyelid dermatitis in patch-tested adult patients: a systematic review with a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 14, 18791 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69612-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69612-z

- Springer Nature Limited