Abstract

Considering the influence of dietary factors on inflammatory markers that may affect the disease course in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), this study aimed to assess the association between dietary inflammatory index (DII) score and disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. This cross-sectional study included 158 patients with UC. The Mayo Clinic score was used to determine the disease severity. A food frequency questionnaire was applied to gather the dietary information, then the Shivappa et al. method was used for the calculation of DII. An association between disease severity (dependent factor) and DII score quartiles (independent factors) was conducted by a logistic regression adjusted to different covariates. In this study, 53.8% of participants were in remission or had mild disease activity. The mean DII score was − 0.24 ± 0.66. The mean DII score was significantly lower in patients with remission (-0.34 ± 0.71) compared with patients who were in the active phase (-0.1 ± 0.57) of UC (P = 0.02). The results of the logistic regression analysis showed that after adjusting for confounding factors, the odds of severe disease were 3.33 times higher among patients who had a more pro-inflammatory diet compared with patients who had an anti-inflammatory diet [OR: 3.33 (95%CI: 1.13, 9.76), p = 0.02]. In conclusion, there was a significant association between higher intake of a pro-inflammatory diet and UC severity. So, from a clinical point of view, there is a need to apply an anti-inflammatory diet to decrease disease severity in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are immune-mediated diseases of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. IBD consists of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)1. A recent study indicates an increasing prevalence of IBD in Asia by 2035 2. Moreover, these diseases impose a substantial economic burden on patients3.

Although the exact etiology is unknown, it is supposed to be caused by an interplay of genes, gut microbiome, and environmental factors including diet4. Different studies reported the association between various nutrients, foods, and dietary indices and IBD risk, progression, and management5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

The dietary inflammatory index (DII) is one of the dietary indices that rank individuals’ diets based on their inflammatory potential15. This index has a significant association with inflammatory markers16,17. Numerous studies assessed the association of this index with different health outcomes and showed its significant association with an increased risk of diseases characterized by inflammation18,19,20,21,22,23.

Considering that IBD is an inflammatory condition, some studies addressed the relationship between DII score and IBD risk24,25,26. Moreover, a limited number of studies assessed the correlation between DII score and disease activity in IBD patients and provided mixed results. Rocha et al. and Keshteli et al. showed a significant association between dietary inflammatory index and disease activity in patients with IBD27,28. However, Lamers et al. and Mirmiran et al. showed that the DII score was not associated with disease activity in IBD29,30.

Considering the influence of dietary factors on inflammatory markers that may affect the disease course in patients with IBD, and owing to the limited number of studies that assessed the association of DII score and disease activity, this study aimed to assess the association between DII score and disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Methods and materials

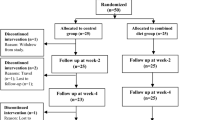

The present cross-sectional study was conducted in the inflammatory bowel disease clinic of Imam Reza Hospital, affiliated with Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. This clinic is one of the focal clinics of IBD management in East Azerbaijan, Iran. From July 2022 to March 2023, 158 patients with UC were recruited. For calculating the sample size, in the PASS software, the regression analysis section was selected. The information for sample size calculation was elucidated from the study by Jowett et al.31, and the power of 80% and confidence interval of 95% were considered.

The patients included in the present study if they were 20–60 years old, and had confirmed diagnosis of UC at least six months before contribution. The patients who had other digestive illnesses, malignancies, autoimmune diseases, or other illnesses that require a different dietary regimen were not included.

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. All patients signed an informed consent form for participation. Besides the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences has approved the study (Ethics code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.694).

Demographic and lifestyle characteristics included in the present study were age, sex, marital status, education, and smoking and alcohol consumption.

The information regarding the disease such as disease duration, extension, drug use, and comorbidities was completed by an expert gastroenterologist. In addition, an expert gastroenterologist and endoscopist used the Mayo score to determine the disease severity. This score consists of four subscales including rectum hemorrhage, defection rate, physician’s global assessment, and outcomes of endoscopy. Each subscale was scored from 0 to 3. The scores were summed up, with a possible score range of 0–12 for total Mayo score. We considered a total Mayo score < 6 as an inactive or mild disease severity, and a score ≥ 6 as a moderate or severe UC stage.

The anthropometric measurements including weight and height were measured by an expert dietitian and according to standard protocols and instruments (SECA weight scale), and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated by subtracting the weight (kg) from the square of height (meters).

For calculating the dietary inflammatory index (DII), the mean daily dietary intake of 30 food parameters (energy, carbohydrate, protein, cholesterol, total fat, Mono-unsaturated fatty acid, ω-3 fatty acids, ω-6 fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acid, fiber, caffeine, tea, garlic, onion, B-group vitamins including B12, B9, B6, B3, B2, B1, other vitamins such as vitamins A, C, D, vitamin E, β-carotene, minerals including Iron, Magnesium, selenium, and zinc) was obtained using the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that was completed by an expert clinical nutritionist. Then, the DII was calculated according to the method developed by Shivappa et al.15. For this, the z-score was calculated and converted to a centered percentile score. Then this value is multiplied by its respective overall food parameter score. Finally, the DII score was calculated by summing all food parameter-specific DII scores. A more positive score indicates a more pro-inflammatory diet and a more negative score indicates a more anti-inflammatory diet.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS statistics-26 software. The normality of data distribution was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The numerical data was presented as mean and standard deviations. The nominal and categorical data were reported as frequency and percent. The calculated DII score was categorized into the quartiles. The differences in numerical data across quartiles were measured using one-way ANOVA. The nominal and categorical data were compared using the chi-square across quartiles. An association between disease severity (dependent factor) and DII score quartiles (independent factors) was conducted by a logistic regression. The regression result was adjusted to demographic, dietary, and disease-related variables.

Results

In this cross-sectional study, the data of 158 patients with ulcerative colitis including 84 males and 74 females were analyzed. According to the Mayo Score, 53.8% of participants were in remission or had mild disease activity. The mean DII score was − 0.24 ± 0.66 which was significantly lower in patients in remission (-0.34 ± 0.71) compared with patients who were in the active phase (-0.1 ± 0.57) of UC (P = 0.02). The comparison of the mean intake of 30 food items considered in the DII calculation was provided in Supplementary Table 1.

The demographic and disease-related characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. As can be inferred, there were significant differences in age (p = 0.003), and total Mayo score (0.02) across quartiles of DII score. However, there were no significant differences among groups regarding the other demographic, disease-related, and nutritional factors (p > 0.05).

The results of the logistic regression analysis of disease severity and DII are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted model, the odds of severe disease in patients with UC were increased with increasing the DII score (indicating a predominantly inflammatory diet). In both adjusted models the association between disease severity and DII score quartiles remained significant. The final model showed that the odds of disease severity were 3.33 times higher among patients who had a more pro-inflammatory diet compared with patients who had an anti-inflammatory diet [OR: 3.33 (95% CI: 1.13, 9.76), p = 0.02].

Discussion

Previously, in an umbrella review, the significant effect of a pro-inflammatory diet on the incidence of different chronic conditions such as myocardial infarction, oral cancer, respiratory cancer, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, overall cancer, and all-cause mortality have been reported23. In the present study, we hypothesized that a pro-inflammatory diet may also associated with the disease activity in patients with UC. The result of this study showed that the mean DII score was significantly higher in patients with active disease compared with the patients in remission or who had mild disease activity. Moreover, the result of regression analysis indicated that after adjusting for demographic, disease-related, and nutritional confounders, the odds of disease severity were significantly higher among patients who had a more pro-inflammatory diet than patients who had an anti-inflammatory diet. This finding was in line with the result of a recent study by Rocha et al. that showed a significant association between dietary inflammatory index and disease activity in patients with IBD28. In a clinical study, Keshteli et al. showed that increasing the intake of anti-inflammatory foods and decreasing the intake of pro-inflammatory foods were effective in preventing subclinical inflammation27. However, some other studies showed conflicting results. In a study on 161 patients with UC, Lamers et al. showed that the DII score was not associated with disease activity score29. In another study of IBD patients, Mirmiran et al. showed no significant association between DII score and disease activity. In the mentioned paper, the separate result was not reported for UC and CD30. The conflicting results of different studies may be partly related to the differences in the methods of disease activity determination. For example in the present study, we used the Mayo score for the determination of disease activity, however, Lambers et al. used the Patient Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index in this regard29. Moreover, the number and types of food items used in determining the DII score could also affect the results.

The significant association between DII score and disease activity in the present study may be partly attributed to the effect of a proinflammatory diet on increasing the inflammatory cytokines such as C-reactive protein (CRP). Previous studies showed that increasing in CRP was associated with the severity of UC32. In addition, DII was associated with the differential composition of the gut microbiome33. Zheng et al. showed that Akkermansia muciniphila was enriched in subjects who adhered to the most anti-inflammatory diets33. In an animal study, it has been shown that A.muciniphila had a beneficial effect on colitis in mice34 by increasing the level of short-chain fatty acids, and down-regulation expression of the TNF-α and IFN-γ in the colon34. On the other hand, the pro-inflammatory diet was associated with increased levels of A. intestine. Prior studies showed the positive correlation of this bacteria with circulating Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)35. PAI-1 is a pro-inflammatory marker that exacerbates mucosal damage by blocking tissue plasminogen activator-mediated cleavage and activation of anti-inflammatory transforming growth factor-beta36.

The present study suffers from some limitations including the cross-sectional design that limits inferring the cause-effect relationship. Furthermore, this is a single-center study, however, this center was one of the main centers of IBD treatment in the northwest of Iran. Besides, the dietary data was gathered using the FFQ. The limitations of this method such as measurement error could affect the study result. Although the association of DII and disease severity was adjusted for different confounding variables, some unidentified and residual covariates could not be controlled. Besides, the intake of some food parameters was not considered in the calculation of the DII score.

Conclusion

The findings of the present cross-sectional study revealed a significant association between higher intake of a pro-inflammatory diet and UC severity. So, from a clinical point of view, there is a need to design an anti-inflammatory diet to decrease disease severity in patients with ulcerative colitis, from a research point of view, owing to the potential limitations of this study, more prospective studies and clinical trials studies are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

Data availability

Data will be available by reasonable request from the corresponding author, Dr. Zeinab Nikniaz, Email: znikniaz@hotmail.com.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DII:

-

Dietary inflammatory index

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

References

Wang, Y-H., Chen, Y., Wang, X. & Shen, B. Inflammatory bowel disease–like conditions: other immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorders. In: Atlas of Endoscopy Imaging in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Elsevier: ; pp. 405–426. (2020).

Olfatifar, M. et al. The emerging epidemic of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia and Iran by 2035: a modeling study. BMC Gastroenterol. 21(1), 204 (2021).

Rahmati, L. et al. Economic burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Shiraz, Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 26(1), 23–28 (2023).

Baumgart, D. C. & Carding, S. R. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 369 (9573), 1627–1640 (2007).

Hou, J. K., Abraham, B. & El-Serag, H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Official J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterology| ACG. 106 (4), 563–573 (2011).

Spooren, C. et al. The association of diet with onset and relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 38(10), 1172–1187 (2013).

Tian, Z. et al. Index-based dietary patterns and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of observational studies. Adv. Nutr. 12(6), 2288–2300 (2021).

Faghfoori, Z. et al. Effects of oral supplementation of germinated barley foodstuff on serum tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6 and-8 in patients with ulcerative colitis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 48(3), 233–237 (2011).

Faghfoori, Z. et al. Effects of an oral supplementation of germinated barley foodstuff on serum CRP level and clinical signs in patients with ulcerative colitis. Health Promotion Perspect. 4(1), 116 (2014).

Sharifi, A. et al. Vitamin D decreases CD40L gene expression in ulcerative colitis patients: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Turkish J. Gastroenterol. 31(2), 99 (2020).

Shirazi, K. M., Nikniaz, Z., Shirazi, A. M. & Rohani, M. Vitamin a supplementation decreases disease activity index in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 41, 215–219 (2018).

Shirazi, K. M. et al. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on remission maintenance in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double-blind controlled clinical trial. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 45(4), 101532 (2021).

Bakhtiari, Z., Mahdavi, R., Masnadi Shirazi, K. & Nikniaz, Z. Association not found between dietary fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols score and disease severity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Nutrition. 126 (112502). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2024.112502 (2024).

Bakhshimoghaddam, F. et al. Author correction: Association of dietary and lifestyle inflammation score (DLIS) with chronic migraine in women: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 18954. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70066-6 (2024).

Shivappa, N. et al. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public. Health Nutr. 17(8), 1689–1696. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980013002115 (2014).

Cavicchia, P. P. et al. A new dietary inflammatory index predicts interval changes in serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. J. Nutr. 139(12), 2365–2372. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.114025 (2009).

Shivappa, N. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and inflammatory markers in the HELENA study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 61 (6). https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201600707 (2017).

Fowler, M. E. & Akinyemiju, T. F. Meta-analysis of the association between dietary inflammatory index (DII) and cancer outcomes. Int. J. Cancer. 141 (11), 2215–2227. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30922 (2017).

Shivappa, N. et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Cardiovascular Risk and Mortality-A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 10 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020200 (2018).

Abbasalizad Farhangi, M., Vajdi, M., Nikniaz, L. & Nikniaz, Z. The interaction between dietary inflammatory index and 6 P21 rs2010963 gene variants in metabolic syndrome. Eat. Weight Disord. 25 (4), 1049–1060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00729-1 (2020).

Farhangi, M. A., Nikniaz, L., Nikniaz, Z. & Dehghan, P. Dietary inflammatory index potentially increases blood pressure and markers of glucose homeostasis among adults: findings from an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Public. Health Nutr. 23(8), 1362–1380. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980019003070 (2020).

Nikniaz, L., Nikniaz, Z., Shivappa, N. & Hébert, J. R. The association between dietary inflammatory index and metabolic syndrome components in Iranian adults. Prim. Care Diabetes. 12 (5), 467–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2018.07.008 (2018).

Marx, W. et al. The Dietary Inflammatory Index and Human Health: an Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Observational studies. Adv. Nutr. 12(5), 1681–1690. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmab037 (2021).

Lo, C. H. et al. Dietary inflammatory potential and risk of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 159 (3), 873–883e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.011 (2020).

Narula, N. et al. Does a high-inflammatory Diet increase the risk of inflammatory bowel disease? Results from the prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study: a prospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 161 (4), 1333–1335e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.007 (2021).

Shivappa, N. et al. Inflammatory potential of Diet and Risk of Ulcerative Colitis in a case-control study from Iran. Nutr. Cancer. 68 (3), 404–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2016.1152385 (2016).

Keshteli, A. H. et al. Anti-inflammatory Diet prevents subclinical colonic inflammation and alters Metabolomic Profile of Ulcerative Colitis patients in Clinical Remission. Nutrients. 14 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163294 (2022).

Rocha, I. et al. Pro-inflammatory Diet is correlated with high Veillonella rogosae, gut inflammation and clinical relapse of inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients. 15 (19). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15194148 (2023).

Lamers, C. R., de Roos, N. M. & Witteman, B. J. M. The association between inflammatory potential of diet and disease activity: results from a cross-sectional study in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 20(1), 316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01435-4 (2020).

Mirmiran, P. et al. Does the inflammatory potential of diet affect disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease?. Nutr. J. 18(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-019-0492-9 (2019).

Jowett, S. L. et al. Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 53 (10), 1479–1484. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.024828 (2004).

Croft, A., Lord, A. & Radford-Smith, G. Markers of systemic inflammation in Acute attacks of Ulcerative Colitis: what level of C-reactive protein constitutes severe colitis? J. Crohns Colitis. 16 (7), 1089–1096. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac014 (2022).

Zheng, J. et al. Dietary inflammatory potential in relation to the gut microbiome: results from a cross-sectional study. Br. J. Nutr. 124(9), 931–942. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114520001853 (2020).

Zhai, R. et al. Strain-specific anti-inflammatory properties of two Akkermansia muciniphila strains on Chronic Colitis in mice. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9 (239). https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00239 (2019).

Yarmolinsky, J. et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 6 (17714). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17714 (2016).

Kaiko, G. E. et al. PAI-1 augments mucosal damage in colitis. Sci. Transl Med. 11 (482). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aat0852 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases Research Center, and IBD clinic staff for their cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by the nutrition faculty, at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. The results of this article are derived from the MSc thesis of Zahra Bakhtiai.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZN and RM were responsible for the conception and design of the study. RM was responsible for funding acquisition, and supervisor. KMS and ZB were responsible for the acquisition of data. ZN and ZB were responsible for data analysis. ZN drafted the manuscript; all authors revised and commented on the draft, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakhtiari, Z., Mahdavi, R., Masnadi Shirazi, K. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Sci Rep 14, 21679 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73073-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73073-9

- Springer Nature Limited