Abstract

At first glance, medical specializations seem to be delineated according to well-defined scientific criteria; the apparently-functional division of labor generates a general hierarchy of specialized knowledge and practice. However, this unequal apportionment of professional power and authority also depends on capitalistic organization. While the medical rationale has always been market-related, starting in the 1980s—with the initiation of its neoliberal agenda—Turkey has enacted progressively aggressive policies, privatizing healthcare service and reconceptualizing it as a dynamic market, thereby forming a medical ethos entangled with neoliberal motifs. In this article, we analyzed how unregulated market conditions give rise to a chaotic scientific field, and how this apparent disorder serves to reproduce an underlying capitalistic logic. Of the multitude of human body parts, we choose the face, because it has become a hot zone in medicine as cosmetic demands from patients have skyrocketed, and because it is an area generating conflict between medical specialties seeking more authority and power. To this end, we interviewed thirty-three specialists from dermatology, otorhinolaryngology, and plastic surgery about their experiences on authority conflicts and their motivations for entering into an unregulated market. Our research highlights how actors in the medical field constitute a relational social context within which boundaries are fiercely negotiated through a market logic. Thereafter, we argue how the ambiguities of pathology, aesthetics, body, and norms that underlie cosmetic procedures are fluidized and become instruments of power, such that this ambiguity has become the very defining characteristic of the scientific field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Medical specializations are usually categorized as settled and institutionally rooted professional fields. However, as with most activities, the conceptual frontiers of the profession are not solid delineations but rather subject to conflicts, mostly resulting from power struggles between expert communities. Moreover, as scientific knowledge has become extremely refined, varied, and multiplied, a division of labor and a rise of strictly demarcated specializations are naturally needed. Within this specialization process, the emergent hierarchy of medical branches has never been an equally distributed role set but instead a dynamic game, wherein the boundaries of medical specialties are continuously fluctuating (Turner, 2007, p.139).

Any given science has as its objective “denial of […] resources to ‘pseudoscientists’ by ideologically employing boundary-work strategies to establish its own legitimacy and authority” (Gieryn, 1983, p. 781). In this process, which could be described as a form of social closure, groups develop strategies that work to gain or retain monopoly by eliminating others through the control of access to resources and opportunities (Weber, 1978). Sciences establish demarcation strategies by distinguishing themselves, not only from the non-scientific: this boundary work, or “doing-distinctions”, can take place across disciplines, sub-specialties, and even individuals, especially in the medical field (Burri, 2008, p. 35). Here, “boundaries demarcate professions from other professions and sub-professions with distinctive status and centrality in the field” (Bucher et al., 2016, p. 499), and in this process there exist “diverse constituents—macro-actors such as government, professional associations, regulatory agencies, suppliers, and consumers” (p. 488). Here, the boundary functions as a kind of conceptual “external perimeter”, where the very notion of boundary implies the existence of ontologically distinct entities. Thus, the essence of a boundary lies in its capacity to define the conceptual distinction between different entities or territories and to exclude them from each other, thus functioning as a separation between fields. The “field”—an autonomous complex social arena with its own set of norms and particular relationalities, where actors contest for power according to their own “feel for the game” (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 61)—is a playground where actors’ spheres of agency are intertwined (Bourdieu, 1980, p. 138). As such, the social field is an intricate web of conflicting patterns, a relational playground where diverse actors encounter and clash with one another; it is only “by examining the struggles for legitimation and domination” that “the very nature of the field itself is revealed” (Collyer, 2018, p. 121).

Within any field, but especially the medical field, the positions of the actors in a dispute do not represent a settled given state of affairs, since external causes, such as technological changes or economic conditions, open up new spaces for renegotiation (Abbott, 1988). In this intricate and dynamic field, formal medical knowledge (Turner, 2007) becomes institutionalized within the focal areas of authority and legitimacy, which grow deep roots over time (Freidson, 1988). Therefore, boundaries in the medical field should not be thought of as given, fixed, and permanently-bounded delineations but rather as being continuously dynamic and in flux, engaging not only within the field but also outside it (Liu, 2018). The external factors of market conditions and government policies not only reproduce those very conditions in terms of health financing (Dingwall, 1977) but also shape the course of the game. In the global context, the progressive adoption of neoliberal policies in particular has escalated the power clashes in the already-conflictual medical field. The field of cosmetic procedures in Turkey—the site of this study—is an example where both the boundary-making and the neoliberalization processes in the medical field have crystallized. In light of these insights, our study will focus on the conflicts and negotiations between the specialties of otorhinolaryngology (ENT), dermatology, and plastic surgery in the field of facial cosmetic procedures.

The neoliberal restructuration of the state in Turkey, through a range of privatizations and the transition to a market logic in existing public services, began in the 1980s with relatively precautious steps, but it became a massive movement and aggressive ideological operation—particularly after 2002, when the current Islamist-guided authoritarian regime of the AKP (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, Justice and Development Party) was established. While the AKP government rapidly redistributed public resources for its own bourgeoisie to profit (Karadağ, 2013), it constructed both an authoritarian regime and an unlimited outsourced public function. This radical transition has paved the way for an intense struggle to obtain greater profits from the privatized and deregulated health service, which has resulted in the transformation of healthcare services into a health market (Keyder et al., 2007; Ünlütürk Ulutaş, 2011; Öniş, 2011; Yılmaz, 2013). As the healthcare sphere has acquired the characteristics of a neoliberal market, the accompanying conflictual environment has become the engine of the field.

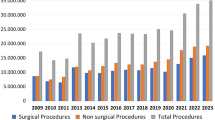

In this neoliberalized health market, the cosmetics industry holds a distinct place (Talley, 2012), which appears to be growing relentlessly in recent years. Globally, in 2021, there were 12.8 million surgical and 17.5 million non-surgical cosmetic procedures performed; Turkey had a total of 950,365 operations in that year, making it the 5th leading country in the cosmetics industry, with a considerable market share (ISAPS, 2022). Facial operations comprise approximately half of the total in this vast industry, accounting for 44% of cosmetic operations performed in Turkey (ISAPS, 2022). Conflicts over medical authority exist within and between the specialties, and the boundaries of medical specialties sometimes violently clash; with the assumption that conflicts in the field of facial cosmetic intervention may intensify due to such a large market share, the study design involved conducting interviews with ENTs, dermatologists, and plastic surgeons, who work in the branches that are authorized to perform facial cosmetic interventions.

Our research took this sociological opportunity to discern the nature of the ongoing conflicts between medical specializations, arguing that they are not scientifically elaborated, rationally delineated, or ethically established fields: instead, we stress that they tend to become battlefields, as far as their manufactured ground of action is positioned at an intersection with other specialties. This tendency reaches its climax when the operational domain deals with cosmetic drives, which, as we will argue, make the conflicts more violent and the frontiers of authority more blurred, in combination with the free-market rationale inscribed in the healthcare field in Turkey.

In light of all this, the current study addressed the research questions of how the authorization frameworks of the medical branches involved in facial interventions are formed, which elements mediate the power and territorial struggles in the field, how medical boundaries are negotiated, and which social factors influence the conditions of negotiation, as well as how all this is articulated within the broader structural conditions in Turkey. Accordingly, throughout this study, we mainly problematize that the professional borders between medical specialties apparently imply rationally defined authority limits, arguing instead that they are in fact subject to harsh conflicts. Specialties aim to occupy larger activity domains, sustained by the politically and juridically unregulated character of the healthcare sector, which promotes ambiguity. Such an unregulated landscape of healthcare functions, together with the hierarchical structuring of the medical field, essentially emanates from the neoliberal policies that reshaped the notion of public service as a capitalist activity. Indeed, the unregulated character of the medical field is neither a coincidence nor an undesired situation, but instead the functioning logic of the healthcare sector as a high profit-promising domain.

The context of the study

Cosmetic industry

One of the main factors contributing to the transformation of the healthcare sector into a health market was the rapid evolution of technological capacities, which transformed not only the practice but also the meaning of the medical profession (Salas and Anderson, 1997, p.193; Timmermans and Berg, 2003, p. 109). New techniques that were rapidly introduced into the medical field—especially those around effective scanning and non-invasive intervention—reconfigured existing treatment procedures and, more importantly, the pre-established authority system (Burri, 2008). Historically, it is only as the quality of medical knowledge has advanced, and as minimally invasive procedures with few interventions and subtle touches have gained a greater foothold in a field, that more specialists or practitioners enter the market (Dowrick and Holliday, 2022). Since various non-surgical procedures (including botoxFootnote 1 and fillers) serve as a passageway to more invasive procedures in the future, it has been argued that these actors utilize minimally invasive procedures as a marketing tool (Vlahos and Bove, 2016). Nevertheless, in this steadily growing market, who can be designated as a plastic or cosmetic surgeon and who can use this title becomes a matter of controversy, as the title itself appears to be an object of prestige (Tansley et al., 2022, p. 163; Webster, 1984). Therefore, it becomes essential to regard the medical field as a field of power, where branches maintain strategies of conflict or reconciliation with each other (Mørk et al., 2010; Turner, 2007; Shiffman, 2015).

Given the enormous market opportunities provided by the cosmetics industry, medical conflicts are inevitably fueled. For instance, unethical advertisements exposing patients are legitimized in the framework of medical discourse by the very actors who perpetuate them (Macgregor and Cooke, 1984), so much so that various scholars have argued that cosmetic surgery threatens medical ethics and even violates the “first: do no harm” tenet of the well-known Hippocratic Oath (Talley, 2012). However, the links between the ethical framework of the medical specialties involved in the beauty business and the fragile borders warped by capitalistic pressure on the actors (physicians, patients, political-bureaucratic actors, etc.) of the cosmetic market have not been treated as a relational whole.

As the question of what precisely defines medical ethics fades, and as the issue of what qualifies as a valid medical indication is no longer clear, the sociological contextualization of the body takes on an even greater significance. Some scholars claim that the body has become a project on which labor is laid and the desired form is achieved (Shilling, 2012), while others argue that women’s bodies have become colonized with the mainstreaming of plastic surgery and its role as an integral part of consumer culture (Talley, 2012), and still others assert that medicalized cosmetic practices construct the body within the scope of gendered and racialized perceptions (Dowrick and Holliday, 2022; Davis, 2003). As the aestheticization of everyday experience emerges as a new regime of truth, the post-modern rationale that is marked by homogenization, commodification, and globalization materializes in cosmetic surgery, and the doctor–patient relation gains a neoliberal character (Talley, 2012). Consistent with this neoliberalized context, the conflict between the branches that intersect on the face—the struggles and conditions that these actors form in the market, and the extent to which the beauty market also affects what we deem as medical in this respect—is a noteworthy absence in the existing literature. Accordingly, this study aims to contribute to the literature on boundary-making within the medical field, the extent to which this boundary-making is intertwined with external factors such as market conditions and political conditions, and the reflections thereof in the market of cosmetic procedures, with an empirical example from the Turkish context.

The Turkish case

The modes of production are reproduced not only economically but also in the political and ideological spheres at the same time, whereas medicine—itself embedded in a certain mode of production—can only exist in articulation with it, indicating the current need to refer to a capitalistic medicine as opposed to the notion of medicine in general (Navarro, 1983). Hence, one could argue that medical knowledge ought to be thought of as interrelated with modes of production. Accordingly, as deregulation policies created a general state that was in line with the neoliberal resetting of the organization of public service, the latter became a generalized cultural fact from the 1980s onward, introducing new values that incited different social fields, particularly professional fields, to readjust themselves to this market-basis rationale of action. Among professionals, medicine has been one of the most salient fields where integration with the market economy had radical consequences that helped to transform the conception of the profession as well as its practice (McGregor, 2001). In parallel with similar tendencies around the world, Turkey has progressively transitioned to a market-oriented notion of public service.

The most radical change in the nature of public service began in the 2000s with the AKP government, which ferociously and aggressively initiated a series of privatizations (Öniş, 2011), including in the most strategic sectors (such as telecommunication and naval construction), which promoted the formation of an oligarchic market order (Karadağ, 2013, p. 151). Considered one of the most promising sectors in terms of profit by AKP politicians, the healthcare service was transformed into a two-pronged set of policies. For the one prong, they reorganized public hospitals to become profit-generating initiatives (Ağartan, 2007; Ünlütürk Ulutaş, 2011)—instead of a part of the social security system—by inducing healthcare workers, especially doctors, to comply with a performance-based competitive environment. For the other prong, they actively encouraged the proliferation of private hospitals (Vural, 2017, p. 279), yet distributed them unequally throughout urban space (Şentürk et al., 2011, p. 1126), signaling the profit-oriented logic embedded in the initiative (Keyder et al., 2007). Meanwhile, the content of medical education has been slightly tipped toward this market-centered understanding of healthcare service (McKenna, 2012, p. 269) under the weight of the pharmaceutical industry (Holloway, 2014, p. 119), together with new sets of values among medical students (Civaner et al., 2016, p. 268). Thus, a generalized hegemonic status—involving a structural setting (Mayes et al., 2016, p. 266) and an ideological legitimacy of the healthcare service (Sointu, 2020, p. 862)—has been established, among professionals as well as citizens.

Methodology

A “case” is often defined in social science research as something that is “out there”—for example, a community, an empirical unit delineated by time and space, waiting to be explored—but it is important to remember that there is no strict definition of a case, and its definition varies (Ragin, 1992, p. 6). To wit, a case can also be something that is constructed, together with the construction of a specific social phenomenon as an object of research (p. 8). A case can be conceptualized either as an empirical unit—which leads to the view that “cases are found”—or as a theoretical construction—which leads to the view that “cases are made” (p. 9). Following the latter perspective, the case in our study can be positioned as facial cosmetic procedures in Turkey, which we constructed as our object of research; our unit of analysis in the construction of this case is a group of actors involved in the field of facial procedures. The reason for problematizing this case, as discussed in the introduction, was the larger theoretical question about the construction of the boundaries of specialties in the medical field.

Worldwide, Turkey ranks 5th in surgical aesthetic interventions and 7th in total surgical procedures (ISAPS, 2021, p. 35; 2022, p. 35). The majority of all aesthetic surgical interventions performed in Turkey are face & head interventions and particularly rhinoplasty (2021, p. 21; 2020, p. 19). The fact that Turkey ranks among the top countries worldwide in surgical procedures, together with its noticeable dominance of facial interventions (especially rhinoplasty), points to a special focus area in Turkey’s cosmetic surgery landscape. Drawing on these early insights, this qualitative study was conducted with professionals from three specialties that are authorized to intervene on the face and have overlapping practice areas: dermatology, plastic surgery, and otorhinolaryngology.

This study focuses on several findings from a field study conducted between March 26, 2022, and November 11, 2022. The research project, registered under the number E-65364513-050.06.04-17942 on December 28, 2021, was approved by the ethical committee of Galatasaray University. A total of 33 participants were interviewed for this qualitative study, specifically 11 dermatologists, 11 otorhinolaryngologists, and 11 plastic surgeons. The sample was diverse across various factors such as gender, type of organization, and years of expertise in order to ensure that the analysis was bolstered by differing perspectives.

Table 1 illustrates the demographics of our interviewees.

Since the study was designed as a qualitative study that prioritized making sense of the participants’ attitudes, opinions, and perceptions about the subject, semi-structured interviews were chosen as the research method. Interviews were conducted via online platforms such as Zoom or Skype, with the specific platform depending on the interviewee’s preference. Interviewees were recruited through snowball sampling. Before the interviews, the participants were told that they could withdraw from the research without giving any reason, that the recorded interviews would only be raw data and would be anonymized, and that they could also withdraw after the interview without providing any explanation. After the participants’ verbal consent was obtained, all of the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. After the interviews were transcribed, a detailed examination of the transcriptions identified commonalities across all interviews, and the raw data were coded through NVivo. A nested, embedded coding system (i.e., a sub-coding system) was utilized to provide a comprehensive view of the field, to prevent the loss of precious information during coding, and to “enable more fine-grained analysis of the data corpus” (Saldaña, 2013, p. 79).

Taking into account the differences that Qualitative Data Analysis programs may bring to the analysis process, we used the three-stage analysis process systematized by Deterding and Waters (2021) through NVivo. NVivo opens a space for both in-case and cross-case analysis (Bonello and Meehan, 2019). The preliminary step is the creation of cases. The case is the unit of analysis in NVivo and is created in this study by collecting the interview transcription of each participant, their demographic information, and the annotations of that interview into a node. In-case analysis is the first step, wherein each individual interview is contextualized by evaluating the qualitative and quantitative data together. In this first stage of the analysis process, notes taken throughout the field study were added to each individual case using NVivo’s memo function and were linked to the appropriate places in the transcriptions. This stage was also part of the data exploration and creation of the free codes (p. 488). Next, all the transcriptions were read carefully in an exploration of the main storyline, after which came the index coding phase, which examined larger paragraphs. The interviews were categorized so that each question in the interview guide corresponded to a major concept. The concepts that emerged in the index codes allowed us to become familiar with the data in a more systematic way and thus construct the analytic codes more reliably, by allowing a more focused reading.

See Table 2 for the index codes that emerged at this stage.

A cross-case approach was applied between these unit of analyses, and a second reading was undertaken to clarify the relationships between the concepts for in-depth exploration. This second step, which involved comparing index codes from individual cases with each other, opens up a space to compare and contrast between different cases—that is, the attitudes, ideas, and narratives in each separate individual document—to detect patterns and themes and to transcend individual cases (ibid.). In this way, index codes filtered from free codes can be grouped under larger themes. At this stage, insights about the analytic codes also began to emerge. “As a means of reflexively improving the analysis by provoking dialog between researchers” (p. 6), a double-coding process was implemented (O’Connor and Joffe, 2020).

At the third stage, a third reading of all interviews by code was conducted using NVivo’s clustering feature for each analytical code, to identify any misquotes, and all quotes were revised accordingly, and the frequency table function was also used. After this stage, the analytical codes were revealed, and the clusters across individual cases were identified. The notion of ambiguity, a recurring theme in all the interviews, was selected from a much wider range of different clusters, in order for this study to analyze how cosmetic intervention—as a notion at the intersection of the ambiguities of the body, pathology, medical indication, and political regulation—resonates with the experiences of participants from three different medical specialties.

Discussion

The ambiguity of body, pathology, aesthetics, and norms: toward a relational field

In any given context, categories tend to present themselves as unmediated and untainted reflections of a pre-existing reality; however, they are fictive schemes of understanding, conjugated by a particular set of social, historical, and cultural conditions (Foucault, 1966). Likewise, the arbitrariness of the notion of pathology—namely, how the very construction of what is deemed pathological and what is regarded as normal only finds relevance within certain historical, social, and political frameworks—has been thoroughly discussed by Canguilhem (1974) and several other scholars (Foucault, 1963; 1975; Hacking, 1998; 1999; Jasanoff, 1996; Rose, 1998; 2007). The very concept of pathology, on which modern medicine relies to diagnose and treat diseases, emerges as one of the most debatable categories in cosmetic procedures. In the case of cosmetic interventions, the natures of both categorization and pathology crystallize, as what gets categorized as pathology is intertwined with a notion of aesthetics—since, according to the interviewees, the notion of aesthetics is not definitive, and it cannot be fixed to a particular indication. It is possible to find some indications of such indeterminate medical knowledge in the perceptions of specialists in the field, when discussing whether unattractiveness can be considered as a pathology (Aquino, 2022) and, hence, an indication for cosmetic surgery.

Chemical peeling for blemishes… If we consider these spots a disease, chemical peeling can be considered a treatment rather than an aesthetic procedure. See, it can be tough to distinguish between aesthetics and treatment in our field. (Interviewee 3, Dermatologist)

For example, a patient comes in healthy, robust, a person without any problems. But the middle of his cheeks are sunken. […] He also looks much older than his age. Now, if we plan a hyaluronic acid injection, that is, a filling application, will this be aesthetic or treatment? […] Now this is a treatment to improve the aesthetic appearance. Yes, it is an aesthetic concern. What is aesthetic concern? It is a social concern. So is this a sufficient reason for us to categorize it as an indication? Yes, it is. (Interviewee 32, Dermatologist)

In the context of cosmetic interventions, this blurring of distinction between aesthetic procedures and medical treatments also has implications for the concept of health, which is a clinical derivative of the notion of “pathological” (Canguilhem, 1974). As the interviewee quotes indicate, the determination of aesthetic flaw and imperfection as indications can also be considered a changing paradigm in the categorization of health, wherein aesthetic concerns are positioned as part of the overall well-being of an individual. This blurring of the lines between medical necessity and aesthetic desire, which precedes a clinical amalgamation of the notions of health and beauty, can be positioned in a broader context, namely within the overarching framework of neoliberalism, which render the latter two a commodity (Talley, 2012; Gimlin, 2000). In our field study, we observed that this neoliberal logic left our interviewees in an ambivalent position. Medical specialists complaining about the commodification of health find themselves in a critical position, but they can rarely escape the market-oriented medical practice, since the “rules of the game” are “designed to encourage health professionals to play the market game within and between hospitals” (Kurunmäki, 1999, p.110). Although they frankly affirm their precautions concerning an aggressive proliferation of the medical cosmetic market, the socially-encircled domain of their practice is largely shaped by the various actors of the game, from the Ministry of Health to self-proclaimed estheticians. Even though they severely criticized the medical interventions that have rapidly become commercialized procedures, they defended themselves by stating that continuing in their profession requires their harmonization with market requirements, which they claimed to be ‘out of their control’.

Now rhinoplasty has indeed become a commodity, and it is becoming more and more so. A means of consumption. And unfortunately, it is out of the physicians’ control. The profession is about to transform into only satisfying customer-based demands. (Interviewee 13, Otorhinolaryngologist)

In aesthetic interventions on the face, something like an artifact contract is signed. […] Since the face is directly in front of the public eye and falls under the artifact contract, you are promising contentment. (Interviewee 17, Otorhinolaryngologist)

Given this, one can argue that what was once clearly defined can become ambiguous as new understandings emerge, or that the relevance or meaning of categories—and, by extension, boundaries—might change depending on the context, making them ambiguous in different situations or environments; this can be seen in the notions of pathology, health, beauty, cosmetic intervention, and medical treatment, which seem to have undergone a transformation through the neoliberal reconfiguration of the health sector. By “ambiguity”, we refer to a lack of clear distinctions, varying interpretations, evolving definitions, situational variability, and cross-specialty discrepancies in the definitions of various categories of the medical field, which are considered scientifically established and circumscribed by boundaries that are regarded as scientifically delineated. We argue that, when medical categories such as “pathology” and “aesthetic flaw/imperfection”, “health” and “beauty”, or “medical treatment” and “cosmetic intervention” overlap, it becomes difficult to determine where one category ends and another begins. This results in confusion and inconsistent application of categories, which leads to different individuals or groups interpreting the criteria for categorization differently, leading to subjective and potentially conflicting classifications that are accompanied by ambiguities and conflicts in boundaries.

Moreover, some phenomena are inherently complex and resist simple categorization—and, according to our interviewees, the body is one of them. Although it has been atomized by modern science in an effort to divide nature into more easily understandable and interceptive units (Foucault, 1963), the body itself is intertwined in a way that cannot be reduced into categories of modern medicine—for at its simplest, as our respondents explained, the body exists as a living organism, and all units within its organic boundaries are inextricably linked to each other and function in conjunction with each other to sustain life and maintain equilibrium.

The human body is a whole, and we have compartmentalized it. In fact, the human body is one; all organisms work together, and nothing is isolated from one another. […] Thus, it’s expected that many branches are involved in the same area. (Interviewee 5, Otorhinolaryngologist)

They [boundaries] are somewhat intricate. The exact boundaries cannot be separated; in the body, every part is related. Therefore, one cannot say one area belongs to this branch and another to that. (Interviewee 28, Dermatologist)

This lack of clarity in the categorization of the body parts is, according to our interviewees, one of the main drivers of the changing definitions and situational variability—hence cross-specialty discrepancies in their categorizations of the clinical practice of cosmetic procedures, which can ultimately lead to different branches being able to perform the same operations and thus power struggles. As reflected in our interviewees’ statements, these overlapping areas of practice arise from the inherent challenge of schematically separating the body, and especially the face, and serve as grounds of legitimacy in boundary disputes. The simultaneous authorization of plastic surgeons to perform all cosmetic surgical interventions, authorization of dermatologists to deal with skin-related issues, and authorization of ENT doctors to perform procedures on the ear, neck, and (especially) nose present a rather intricate map of action regarding facial operations. Here, specialists tend to profit from every opportunity or void to extend their capacity to apply cosmetic procedures that were once defined as under the authority of other specialties. One typical example is rhinoplasty, which was primarily performed by plastic surgeons but is progressively performed by ENT surgeons, based on the argument of corporeal integrity. However, while ENT surgeons claim an authority over rhinoplasty surgeries due to the presence of the nose in the name of their branch, they seem to be voluntarily abandoning prominent ear surgeries, which have relatively less economic benefit, in favor of plastic surgery. Thus, it is the ambiguities of pathology and aesthetics, as well as market conditions, that facilitate boundary conflicts. These ambiguities crystallize visibly when it comes to a body part such as the face, which falls under the intervention of several branches. When asked about the reason for the thorny struggle for authority among the three branches included in this study, the inherently difficult-to-define boundaries of the field of facial intervention were emphasized, along with the financial considerations that trigger these boundary violations:

A general surgeon does not interfere with the surgery performed by a gynecologist, as those are organs with more defined limits of authority. As head and neck surgery is also included in our specialty, it is not possible to draw a border. Therefore, in head and neck surgery, everyone’s fields of practice interfere with each other. Anyone can enter them. (Interviewee 16, Otorhinolaryngologist)

During our internship, when they asked us, “Can otorhinolaryngologists perform rhinoplasty?”, we were laughing uproariously, like “no way, what the hell!” But of course, since it has the word “nose” in its name and there are economic factors involved, this is not questioned any more. Otorhinolaryngologists started to perform rhinoplasty! (Interviewee 21, Plastic Surgeon)

Look, open the website of the Otorhinolaryngology Department. The man wrote ‘Facial Plastic SurgeryFootnote 2 School’ there, shame on him! The man opened a “School of Facial Plastic Surgery”. He is opening a school for another branch. If these procedures are within your branch, why do you use the name “Plastic Surgery”? Because there is 60 years of prestige in the world. We are considered in the top 6 countries in the world. (Interviewee 20, Plastic Surgeon)

However, these boundary-making strategies do not only operate between plastic surgery and otorhinolaryngology: the branch of dermatology, which has limited rights to subcutaneous injections and interventions, also competes in this complex field, both on an individual scale and on the basis of associations—especially for dominance over botox and filler procedures:

The Dermatology Association says let’s get as much as we can. I mean, let’s take botox, let’s take that too, why are other branches doing it. (Interviewee 8, Dermatologist)

Here, we must underline that these overlapping areas of jurisdictions are not merely a cause or an effect; rather, like all other conceptions of norm, pathology, and aesthetics, these indicate a relational existence. The ambiguous character of the social sphere offers a general matrix of relationality, which is not just a structural feature but a composite and dynamic context, a sum of the agencies of a variety of actors (insiders and outsiders) involved in the cosmetic market, entailing a series of uncertainties woven throughout multiple strategies of profit-maximizing. Based on these insights, we can argue that although scientific terms (here,“pathology” and “indication”) claim epistemic objectivity and are considered embodiments of pure objectivity and rationality, they are also intricately woven into the practical context from which they emerge (Knaapen, 2013). Such terms are not static entities: they are the product of categorizations whose boundaries are open to constant negotiation, and they are subject to revision and reinterpretation as scientific knowledge and practices evolve. Given that even the definition of science itself is not immune to various economic-political spheres of influence (McLellan, 2021), boundary-making—that is, defining what is scientific and what is not, or deciding what is to be defined within a certain scientific field—itself becomes a social interplay and cannot be considered independent of the sociopolitical relationalities in which it is embedded. Drawing the boundaries of what is included and what is excluded entails drawing the boundaries of who can intervene in this field, and thus it functions as a practical ground of legitimacy for claiming epistemic authority (Burri, 2008).

The above-discussed difficulties in compartmentalizing the body into specialties and the economic motivations that trigger boundary intrusions are significant. In addition to these, our interviewees also identified the increasing over-specialization of the medical field as a contributing factor to boundaries blurring. As medical professionals become more narrowly focused on their specialties, clear delineation of roles and responsibilities becomes more difficult, leading to overlaps and uncertainty in professional areas:

The intricacies of life and anatomy do not allow otherwise. Because everyone’s field has narrowed considerably. Therefore, I don’t think any branch of medicine can say that only they are dealing with this area. (Interviewee 21, Plastic Surgeon)

As the process of categorization in the interpretation of the human body in cosmetic interventions itself becomes ambiguous, the answer to the question of who can intervene moves away from scientific foundations and becomes dependent on negotiations within a particular political economy, so much so that the ambiguity becomes a tool for new actors—both medical and non-medical—to utilize as an infiltration strategy, as will be discussed in more detail in the following sections. As the cosmetic procedures sector encourages newcomers from everywhere to take part in the market structure it promotes, competing actors try to intrude through the best adaptation strategy possible, such as inventing attractive but ungrounded titles to legitimize the position they aim to occupy (e.g., medical esthetician, beautician, facial plastic surgery, etc.). In the case of cosmetic surgery, ambiguity—specifically, the vagueness of which branch is authorized to perform which procedure—is not an undesirable outcome but in fact one of the defining elements of the field itself.

Strategies in the battlefield: rearrangement of medical authority

Although the frontiers of medical authority between specializations have never been stable or clearly defined (given that the human body is a total but also fluent entity), the rise of market rationale and the technology-intensive remaking of medical practice caused widespread changes in the redistribution of medical authority across specializations while highly blurring the technical and ethical frontiers. In line with the market pressure on medical specializations that incites them to enlarge or redefine their boundaries of authority, their once-juridically fixed professional positions have been partly abandoned. Thus, dermatology—which was mostly concentrated on the illnesses of the surface of the skin—began to intervene in deeper layers of the flesh, while otolaryngology sought to extend its territory of operation to cosmetic procedures on the face, slightly transgressing its borders. Plastic surgery, which is the only specialization that is not related to any specific organ, has been juridically disoriented, given that most of the operations they were once expected to do for cosmetic motivations (such as rhinoplasty, face lifting, or reconstructive surgery) are either shared with or confiscated by other specialties, essentially by otorhinolaryngology. All parties engaged in this uncertain domain persistently try to determine the frontiers of their authority and those of their competitors. We observed that the more competitive the facial procedures market becomes, the more that conflicts for power tend to intensify, which in turn ignites juridical struggles between professional associations. In this power game, where cards are remixed and redistributed under market pressures (Bourdieu, 1988, p. 10), specialty associations emerge as significant actors in the conflict, who implement various strategies to increase their market share through their relations with the government, ministries, and the public. When asked about the relevant organizational strategies, interviewees responded as follows:

Plastic surgeons pursued an aggressive policy for 40–50 years. They officially became a branch from nothing; their association was founded in 1962. […] After this association was established, they declared war on other branches. With very aggressive policies, using television, newspapers, etc., they tried to create an image that this work belongs only to plastic surgeons. (Interviewee 16, Otorhinolaryngologist)

Power and numbers speak between associations. Unfortunately, this is the case. Some very dangerous things happen. For example, we call them dentists, but they are not actually medical doctors. You see, because there are so many of them, there is an arm-twisting, including in rector elections. […] Especially when a branch is in charge of the Board of Medical Specialization,Footnote 3 they can do these things much more easily. (Interviewee 20, Plastic Surgeon)

Some authority transgressions are sued by those who defend the monopoly of a certain domain of practice, and the courts decide to limit medical abilities in a juridical sense or completely ban them for certain members of other specializations, meaning that gatekeeping strategies are implemented in order to safeguard the current boundaries (Collyer et al., 2017); nevertheless, either these regulations are not applied, or the actors negatively affected by them find out some legal—or even illegal—methods to bypass them. This can be interpreted not only within the limits of the medical field and its rising commercial character but also, more profoundly, in relation to the continuous corrosion of the rule of law (Çalışkan, 2018; Esen and Gümüşçü, 2016) under the ever-more authoritarian tone of the AKP regime, which systematically controls, intervenes in, and directs juridical instances and institutions through the expansion of political oppression on its officials, such as judges, attorneys, members of higher courts, etc. Through authoritarian liberalism (to use the widely-shared oxymoronic description for the AKP government), such political ambition acts on the health market both by coercive force, through the establishment of a quasi-total control on juridical order, and by weightless liberalism, which lets commercially motivated actors enter the medical cosmetic field without confronting any obstacles. The heterogeneous milieu of medical cosmetic interventions also seems to be implicitly encouraged by the government, either by covert incentives or deliberate inertia:

Today, there is a field struggle in plastic surgery that has accelerated a lot in the last five years […] Title usurpation, field violation… The use of specialties and titles that do not exist, the state’s indifference and lack of intervention… (Interviewee 23, Plastic Surgeon)

However, this state of border uncertainty and disputes was not necessarily met with criticism in our fieldwork—on the contrary, while the plastic surgery branch (which had to share many procedures with otorhinolaryngology) reacted negatively to the lack of intervention by the state and ministries, ENTs tended to interpret this as a means of legitimization:

ENTs are authorized to perform procedures on the face. This includes botox, fillers, aesthetic procedures. As you know, we do rhinoplasty, even more than plastic surgeons. […] We have already been authorized by the Board of Medical Specialization appointed by the Ministry of Health! In this sense, we are at peace, both in front of the ministry and in our own consciences. (Interviewee 5, Otorhinolaryngologist)

In addition to juridical cases, the power struggle also occurs through the guidelines of specializations, a process through which state institutions (such as the Ministry of Health) are directly or indirectly involved. Indeed, professional guidelines—similar to the phenomenon of medical scientific terms discussed above—can also be considered inherently political, as standardizations become a kind of negotiation tool in the struggle for authority within the scientific field (Castel, 2009, p. 755). In the case of cosmetic procedures, the preparation of professional codes—which constitute the basis for the principles in resident formation in a medical specialization—becomes another gray zone, despite proponents spending considerable efforts to define them. However, the Ministry of Health enters the power game as a kind of pro-market deus ex machina, motivating all actors to adopt a mercantile logic instead of playing a regulatory and balancing role. In line with the profit-oriented public service policies of the government, our interviewees stated that the Ministry of Health plays a double role in managing the health market: it intervenes by promoting non-medical and commercial actors to be influential components without much considering the medical authority question, and it does not adopt what should be its regulating role as a public decision-maker.

There are some legal instances that demonstrate the intentional ambiguity inscribed in the market. For example, in 2018, the Council of State overturned a lawsuit filed by dermatologists and plastic surgeons regarding the restriction on the authorization of other branches applying botox and recognized the jurisdiction of other specialties, such as dentistry.Footnote 4 Furthermore, in further regulations published in the Official Gazette, the former status of beauty centers as health institutions was revoked, and their supervision was transferred from the ministry to the municipalities.Footnote 5 In other legislation, “beauticians” were legally recognized, and their limits of authority were determined.Footnote 6 All of these both delegate legal responsibility from a centralized authority to various actors and encourage different actors to get involved in the cosmetic interventions field. Thus, the Ministry of Health lets a field that is already juridically and institutionally a gray zone function with its own pragmatism—in other words, in terms of pure market rationale. This, in turn, makes a priority list placing the capitalistic motivation at the top inevitable, so much so that the policies of the Ministry of Health were frequently stressed when interviewees were asked about possible explanations behind borders becoming so prone to violations despite the presence of established rules and regulations:

As an association, we went to the Ministry [of Health] and explained our problems. They said that there are 250 official hair transplant centers in Istanbul and 850 underground. We questioned why they were not doing anything, and the state said they were bringing in very good money. (Interviewee 15, Plastic Surgeon)

There are so many people we are after as an association; a man came from Iran, he is a normal medical doctor, a general practitioner, he introduces himself as a plastic surgeon, he has a practice in a five-star hotel in Istanbul. He doesn’t have a license for his practice, people go to him and have procedures done and the Ministry [of Health] doesn’t do anything. (Interviewee 15, Plastic Surgeon)

Fifteen, maybe twenty years ago, the Ministry of Health did something like this: Let’s organize two-month courses, let’s give normal general practitioners a certificate under the name of medical aesthetic certificate. And with this, they can do fillers, botox, cosmetic procedures. The physician who was given a medical aesthetic certificate there did not only fill botox; he also treated blemishes, acne, scars, he did many things. […] How can you give my branch to those people and assign them the title of medical estheticians? (Interviewee 31, Dermatologist)

Given the above, we can argue that the pressure of the market economy is so strong that it incites the actors of the field to legitimize actions that are destined to break the once-established balance of power and its apparently scientifically founded rules. Consequently, not only is the economic side of medical practices on the face remodeled, but also the ethical considerations characterizing the internalized contours of medical authority are highly blurred. Naturally, whenever such an ethical uncertainty prevails, actors tend to develop discursive instruments that allow them to legitimize the entrepreneur posture they tend to interiorize.

Toward a flexible ethos

As the appeal of cosmetic procedures has attracted actors from many different fields, it has become necessary for physicians to develop various neoliberal strategies, such as advertising and marketing their services (Macgregor and Cooke, 1984), in order to survive in an increasingly crowded game. This has sown the seeds of commercial medicine (Sullivan, 2001) and thus morphed the very notion of medical ethics (Au, 2022; Sullivan, 2001; Hofmann, 2019; Vlahos and Bove, 2016), reconfiguring healthcare as a commodity. Our field study reveals that various facts—such as the proliferation of beauty centers and salons, and certificates and titles of specialization distributed without supervision, as embodied in certain striking examples—have encouraged even those who only finished primary school to enter the medical field without any actual expertise. In this contentious struggle, the ambiguous nature of the field has become a valuable asset in a milieu dominated by the pursuit of economic dynamism, so much so that the dissolution of the boundaries between medical specialties is itself constitutive in the power struggle of actors. This is a striking illustration of how the boundaries of medical specialties are not shaped by rational ideals but rather demarcated and distorted in a game of power (Bourdieu, 1980) full of conflict and compromise (Turner, 2007; Shiffman, 2015). Of course, the intertwining of scientific knowledge with the social and the political is not a new phenomenon (Jasanoff, 1996); however, when it comes to cosmetic procedures, the medical ethos—re-conjugated by a neoliberal grammatical mode through the overwhelming dominance of economic motivations over scientific rationale—is characterized by chaos itself. This chaos is in a symbiotic relationship with money and power (Habermas, 1987). The ongoing commercialization of healthcare services in Turkey gave way to the intrusion of various semi- or non-competent actors into the market, which was fundamentally stimulated by the attractiveness of cosmetic procedures; these actors had the help of political and bureaucratic agents (particularly the Ministry of Health), who pushed the commercial drive so as to financially animate the medical field or were passive toward the invasions of outsiders, such as self-proclaimed “cosmetic surgeons”, “cosmetic or esthetic specialists”, “estheticians”, dentists, residents, and medical specialists from unrelated domains or positions. While seemingly contrary to the raison d'être of the Ministry of Health, its stance of encouraging non-medical or non-specialized actors in the market is in line with the AKP government’s purely capitalistic understanding of public services. As a result, the ministry has permitted all actors who enter the market to easily engage in a political game of both economic competition and profit-making. The resultant unregulated and complex character of the cosmetic health market has created widespread dissatisfaction among doctors:

There are [medical] assistants on the beaches with fillers and botox in their bags like peddlers! Our assistants are doing botox and fillers alongside corn and mussel vendors! Such behaviors are dishonoring to the profession. […] Money is the only root of the problem. (Interviewee 15, Plastic Surgeon)

Well, nobody wants to remove a chin tumor. No one is in the race for it. But everyone is desperate for an eyelid operation, lip augmentation, or nose surgery. Why? Because there’s money there. Wherever there’s money, there’s a fight. (Interviewee 25, Plastic Surgeon)

Boatloads of patients flood into Istanbul, Turkey for hair transplantation and aesthetics. They are charged 10,000 euros for a rhinoplasty! And people pay! (Interviewee 7, Otorhinolaryngologist)

Our interviewees emphasized that along with this paradigm transformation in medical ethos regarding cosmetic interventions, there is also a significant shift in the perception of the patient’s body, which is no longer just an entity to be treated by the physician but a living, breathing advertisement for the physician’s skills and reputation. Cosmetic procedures—where any defect is immediately visible and can directly affect the reputation of the physician—provide external and highly visible changes that are subject to public scrutiny and personal judgment; consequently, “results” become a direct reflection of the physician’s expertise. This not only adds a new facet to the concepts of professional responsibility and reputation, but also blurs the lines between medical treatment and personal branding, making it a matter of public exposure. In other words, this transformation is not only concerned with treating diseases, but also with meeting society’s expectations of beauty and perfection.

If you remove someone’s tonsil, it is not directly visible from the exterior. But in our practice, the flaw immediately attracts attention! Then people will question who did it. And it becomes a poor advertisement, bad publicity for you. (Interviewee 1, Otorhinolaryngologist)

Our job is like putting your signature on people’s faces. When you don’t meet expectations, you will have problems. (Interviewee 7, Otorhinolaryngologist)

However, this change in ethos should not be considered unilateral: various facets of a pre-existing transformation on the part of healthcare providers crystallize when it comes to aesthetics. For example, according to our respondents, plastic surgeons, dermatologists, and otorhinolaryngologists are now shifting from reconstructive or cancer surgery to cosmetic procedures; as a result, medical interventions that require many years of experience have begun to be abandoned, and the fact that these fields are not economically appealing to physicians has changed the notion of professional dedication. In addition, our respondents indicated that their students want to go into areas such as fillers, botox, and cosmetic surgery, which offer better financial gains. In the field, a kind of disillusionment—triggered by “external” factors such as economic conditions, harsh working conditions, etc.—also shapes the practical choices of newcomers (Becker and Geer, 1958), with individuals making context-informed decisions as they navigate the “realities” of practice and position themselves within it. Moreover, it must be highlighted that this phenomenon is not limited to residents, as medical specialists are also taking aesthetic courses and leaving their specialties to pursue cosmetic procedures:

The intensive care physician thinks, rightfully, why should I get tired in the ICU when I can go and do cosmetics in an enjoyable way and not have my patients die. Cardiovascular surgeons do not operate, they do cosmetics. Neurosurgeons do not operate, they do cosmetics. Intensive care unit staff do not take care of the sick, they do cosmetics. We will die, but we all will die pretty. (Interviewee 31, Dermatologist)

I will quote the last tweet I read. A cardiac surgeon, an internist, a pulmonologist, a thoracic surgeon say that they gathered at a medical aesthetics training course. (Interviewee 7, Otorhinolaryngologist)

In Turkey, after completing their undergraduate education, aspiring physicians are required to take an exam, starting their residency programs and selecting a specialization based on their scores. The changing tendencies have even influenced the scores at which departments accept students, with the expected exam scores increasing for departments that specialize in cosmetic surgeries:

In my time, dermatology used to admit students from the middle ranks [of the specialization exam ranking]. Now it recruits only the top 50. There’s a big market […] General practitioners from many branches, cardiovascular surgeons, even obstetricians and gynecologists have started to enter into these practices little by little. (Interviewee 18, Otorhinolaryngologist)

With regard to all the above, we must underscore that the social field that this study attempts to visualize is relational. Neoliberalism, which establishes uncertainty as the basis of its existence, makes the field even more amorphous, but ambiguity does not mean the absolute absence of order; instead, ambiguity itself becomes the norm. Because every power is related to a certain structure of knowledge, there cannot be a way of knowing that is independent of power (Foucault, 1975). In this context, neoliberal power has created its own way of knowing, which in turn has opened new channels of power. Within this new matrix of relations, the power struggles in the field render uncertainties into a tool that can be converted into profitability, and they construct these uncertainties as a strategy for opening up a new space for specialists in this chaotic field. Eventually, all of the ambiguities mentioned in the article—namely the body, pathology, aesthetics, and norm—have created a market: a market of uncertainty.

The setting of an unregulated health market

The complex struggle in the medical interventions market encompasses a range of diverse stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Labor and Social Security,Footnote 7 insurance companies, technology marketers, pharmaceutical representatives, hospital organizations, physician associations, educational and training institutions, so-called non-medical beauticians, salons, legislators, regulators, physicians, patients, courts, and social media. As respondents revealed, medical practice involves crossing the boundaries between specialties and draws in people from many different backgrounds, including those outside of the healthcare field. The interventions of these external actors—who generally have not undergone medical training, and if they have, lack specialization—are ignored by the authorities of the domain, and they are not subject to any inspection process:

He says, “I am a Doctor of Medical Aesthetics”! Who granted you this title? He says, “I just wrote it.” You cannot even do work on a test animal that easily in this country. You cannot inject experimental animals so easily. (Interviewee 20, Plastic Surgeon)

The beautician, not even a doctor, applies fillers, and refers the infected patient to me. Shamelessly! And they can’t even be sued, it’s funny—they can’t be charged because they are not authorized anyways! (Interviewee 8, Dermatologist)

As the interviewees’ quotes indicate, the unregulated nature of the field and its welcoming of external actors has consequences for patient health, creating a context within which the involved actors become ever-more intricate, thereby producing a milieu of medical interventions in which the products used and the competence of the people performing the procedures cannot be evaluated. In the setting denoted throughout the article, the fundamentals of medical ethics and practice are intricately entwined with a body of knowledge that is shaped by the political dynamics of state actors, influencing what is regarded as the scientific domain within each medical specialty. Here, it is revealed that neoliberalism is not merely a market logic but an insidious, pervasive, and subtle ideology (Brown, 2003), one that is not an entity apart from individuals or operating at a higher level, but is rather reproduced even in the smallest social units—from physicians to associations, from patients to so-called beauticians. The unregulated nature of the chaotic space—further reproduced by this ideology, which maintains the continuity of the struggle to increase profitability—is not a defect but a functional device. The uncertainty fuels strife and conflict.

Conclusion

Scientific inquiry has prompted progressive specialization in the medical field. Consequently, medical specialties have arisen as scientifically well-founded fields of knowledge and practice, which in turn organized medical power in the form of an indubitable hierarchy of internal division of labor. However, this more-or-less stabilized general medical field has rapidly changed in shape and teleology since the 1980s, with the increasing adoption of neoliberal policies in Turkey (as in several parts of the world) that reduced the social character of public services and replaced it with a merchant logic boosted by private capital. In the neoliberal deregulation of public service, healthcare service has largely been transformed into a health market. One of the most immediate consequences of this shift has been the triggering of authority conflicts between medical specialties.

In our research, we focused not only on the ambiguous setting of these fields in contradiction but also on the relational character of neoliberal healthcare policies, the ambiguous and fluid ontology of the human body, and the aesthetic demands from individuals unsatisfied with their appearance. Once a market logic dominates the medical field, the specialties quickly get into conflicts over authority, legitimacy, and power over certain procedures and zones. We discovered that these conflicts are much more complex than they seem to be, given that the transgressions or invasions of authority are animated not only by opportunistic individual motivations but also by the implicit policies of different political or market actors. However, the most concentrated form of the conflicts occurs at the boundaries between medical specialties, which incessantly try to capture authority from others. Accordingly, we observed that the field of facial operations is characterized by constant frontier struggles, consisting of reciprocal intrusions. Indeed, medical specialties operating on the face constitute, throughout their conflictual relations, a kind of ecological equilibrium, in which doctors are motivated to invade some procedures as yet monopolized by other specialists, while abandoning other procedures to newcomers. Here, we observed the development of a discursive context wherein specialists tend to defend their agencies by two types of argument: integration (coexistence with another specialty) or exclusivity (confiscation of authority). In any case, this power game is almost always legitimized with scientific evidence, more specifically through anatomic morphology. This means that political–ideological battles are legitimized by scientific discourse that aims to make them nearly indubitable.

Another outcome of this conflictual milieu is the accentuation of cosmetic motives in the legitimization of territorial struggles, which in turn initiates a market logic. Thus, the medical specialty gains territory and authority, while developing discursive tools to pathologize ugliness. The insatiable desire for cosmetic alteration by patients feeds the power struggles among the medical specialties, all of which are circumscribed by a neoliberal rationale. Finally, the relationality of the medical field around the face seems to instigate a rapid ethical degradation among medical actors, with particularly the notion of dedication in the profession vanishing, replaced with the crude reality of a quest for money.

In summary, we highlight through our findings that the frontiers between medical specialties are scenes of indefinite conflict zones, instead of clear-cut, well-defined, strictly-delineated limits of authority. This confusion is fed by two kinds of ambiguity, which implicitly coalesce into the reproduction of a neoliberal and chaotic professional field of practice: (1) An unregulated market, with political actors and opportunistic outsiders; (2) Ontological fluidity of the human body, which permits the generation and perpetuation of conflicts for more authority and power. Instead of isolating the conflicts between medical specialists as micro-sociological games, we position them in a broader framework that shows the relational character of the social.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, because some of the participants are government officials and because disclosure of the datasets could expose the identities of the physicians and lead to legal and political troubles; nevertheless, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Our dataset reveals personal and identifying information (in terms of affiliated institutions and participants’ city of residence), which may cause difficulties for the interviewees in Turkey’s political climate. While we value transparency, we prefer not sharing the interviews of our interviewees, as we have a responsibility to them.

Notes

Although the namesake of a trademarked injectable product, Botox® (Botulinum toxin-A) has become a metonym for cosmetic injectables, particularly in the Turkish context. Therefore, the use of “botox” in lowercase throughout the article is as an eponym for subcutaneous injections.

Although it is a recognized branch in certain parts of the world, Facial Plastic Surgery is not a subspecialty that is recognized or defined by legal authorities in Turkey.

The Curriculum Formation System of the Board of Medical Specialization (Tıpta Uzmanlık Kurulu Müfredat Oluşturma Sistemi-TUKMOS), established by the Board of Medical Specialization authorized by the Ministry of Health, shapes the limits of authority of the branches by creating curricula.

For further information, please refer to the “Danıştay 15. Daire Başkanlığı 2015/10115 Esas 2018/3875 Karar Sayılı İlamı” (Certified Copy of Judgement Number 2018/3875 on Case 2015/10115 of the 15th Chamber of the Council of State).

For further information, please refer to the “Ayakta Teşhis ve Tedavi Yapılan Özel Sağlık Kuruluşları Hakkında Yönetmelik” (Regulation on Private Health Institutions for Outpatient Diagnosis and Treatment) still in effect.

For further information, please refer to the “İşyeri Açma ve Çalışma Ruhsatlarına İlişkin Yönetmelik” (Regulation on Workplace Opening and Operation Licenses) still in effect.

The Social Security Institution (SSI), a subsidiary of the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, determines the amount of payment physicians are entitled to receive for each procedure.

References

Abbott A (1988) The System of Professions. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Ağartan T (2007) Sağlıkta Reform Salgını. In: Avrupa’da ve Türkiye’de Sağlık Politikaları: Reformlar, Sorunlar, Tartışmalar, eds. Çağlar Keyder, Nazan Üstündağ, Tuba Ağartan, Çağrı Yoltar, 37–55. Istanbul: İletişim

Aquino YSJ (2022) Pathologizing ugliness: a conceptual analysis of the naturalist and normativist claims in “aesthetic pathology. J Med Philos 47(6):735–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhac039

Au A (2022) Consumer logics and the relational performance of selling high-risk goods: the case of elective cosmetic surgery. Int J Sociol Soc Policy. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-07-2022-0180. Accessed 17 August 2023

Becker HS, Geer B (1958) The fate of idealism in medical school. Am Sociol Rev 23:50–56

Bonello M, Meehan B (2019) Transparency and coherence in a doctoral study case analysis: reflecting on the use of NVivo within a ‘Framework’ approach. Qual Rep. 24(3):483–498

Bourdieu P (1980) Le sens pratique. Éditions de Minuit, Paris

Bourdieu P (1988) Les règles de l’art: genèse et structure du champ littéraire. Éditions du Seuil, Paris

Bourdieu P (1990) Rules to Strategies. In: In Other Words, 59–75. Stanford: Stanford University Press

Brown W (2003) Neo-liberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy. Theory & Event 7(1)

Bucher SV, Chreim S, Langley A, Reay T (2016) Contestation about collaboration: discursive boundary work among professions. Organ Stud 37(4):497–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615622067

Burri RV (2008) Doing distinctions: boundary work and symbolic capital in radiology. Soc Stud Sci 38(1):35–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312707082021

Çalışkan K (2018) Toward a new political regime in Turkey: from competitive toward full authoritarianism. N Perspect Turk 58:5–33

Canguilhem G (1974) Le normal et le pathologique. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

Castel P (2009) What’s behind a guideline? Soc Stud Sci 39(5):743–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312709104435

Civaner MM, Balcıoğlu H, Vatansever K et al. (2016) Medical students’ opinions about the commercialization of healthcare: a cross-sectional survey. Bioeth Inq 13:261–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-016-9704-6

Collyer F (2018) Envisaging the healthcare sector as a field: moving from Talcott Parsons to Pierre Bourdieu. Social Theory & Health 16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-017-0046-1

Collyer FM, Willis KF, Lewis S (2017) Gatekeepers in the healthcare sector: knowledge and Bourdieu’s concept of field. Soc Sci Med 186:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.004

Davis K (2003) Dubious equalities and embodied differences: cultural studies on cosmetic surgery. Explorations in Bioethics and the Medical Humanities. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield

Deterding NM, Waters MC (2021) Flexible coding of in-depth interviews: a twenty-first-century approach. Sociol Methods Res 50(2):708–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799377

Dingwall R (1977) The Social Organisation of Health Visitor Training. Croom Helm, London

Dowrick A, Holliday R (2022) Tweakments: non-surgical beauty technologies and future directions for the sociology of the body. Sociol Compass 16(11):e13044. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.13044

Esen B, Gümüşçü S (2016) Rising competitive authoritarianism in Turkey. Third world Q 37(9):1581–1606

Foucault M (1963) Naissance de la clinique: Une archéologie du regard médical. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

Foucault M (1966) Les Mots et les Choses: Une archéologie des sciences humaines. Gallimard, Paris

Foucault M (1975) Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison. Gallimard, Paris

Freidson E (1988) Profession of medicine: a study of the sociology of applied knowledge. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Gieryn TF (1983) Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. Am Sociol Rev 48(6):781–795. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095325

Gimlin D (2000) Cosmetic surgery: beauty as commodity. Qual Sociol 23:77–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005455600571

Habermas J (1987) The theory of communicative action volume 2, lifeworld and system: a critique of functionalist reason. Beacon Press, Boston

Hacking I (1998) Mad travelers: reflections on the reality of transient mental illnesses. University of Virginia Press

Hacking I (1999) The social construction of what? Harvard University Press, Harvard

Hofmann B (2019) Expanding disease and undermining the ethos of medicine. Eur J Epidemiol 34(7):613–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00496-4

Holloway K (2014) Uneasy subjects: medical students’ conflicts over the pharmaceutical industry. Soc Sci Med 144:113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.052

ISAPS (2021) International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2020. ISAPS. https://www.isaps.org/media/evbbfapi/isaps-global-survey_2020.pdf. Accessed 25 March 2024

ISAPS (2022) International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2021. ISAPS. https://www.isaps.org/media/vdpdanke/isaps-global-survey_2021.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2023

Jasanoff S (1996) Is science socially constructed - and can it still inform public policy? Sci Eng Ethics 2:263–276

Karadağ R (2013) Where does Turkey’s new capitalism come from? Eur J Sociol 54(1):147–152. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975613000064

Keyder Ç, Üstündağ N, Ağartan T, Yoltar Ç (2007) Avrupa’da ve Türkiye’de Sağlık Politikaları: Reformlar, Sorunlar, Tartışmalar. İletişim, Istanbul

Knaapen L (2013) Being ‘evidence-based’ in the absence of evidence: the management of non-evidence in guideline development. Soc Stud Sci 43(5):681–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312713483679

Kurunmäki L (1999) Professional vs financial capital in the field of health care—struggles for the redistribution of power and control. Account Organ Soc 24(2):95–124

Liu S (2018) Boundaries and professions: toward a processual theory of action. J Prof Organ 5(1):45–57

Macgregor F, Cooke D (1984) Cosmetic surgery: a sociological analysis of litigation and a surgical specialty. Aesthet Plast Surg 8(4):219–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01570706

Mayes C, Kerridge I, Habibi R, Lipworth W (2016) Conflicts of interest in neoliberal times: perspectives of Australian medical students. Health Sociol Rev 25(3):256–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2016.119871

McGregor S (2001) Neoliberalism and health care. Int J Consum Stud 25(2):82–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2001.00183.x

McKenna B (2012) The clash of medical civilizations: experiencing “primary care” in a neoliberal culture. J Med Hum 33:255–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-012-9184-6

McLellan T (2021) Impact, theory of change, and the horizons of scientific practice. Soc Stud Sci 51(1):100–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127209508

Mørk BE, Hoholm T, Ellingsen G, Edwin B, Aanestad M (2010) Challenging expertise: on power relations within and across communities of practice in medical innovation. Manag Learn 41(5):575–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507610374552

Navarro V (1983) Radicalism, marxism, and medicine. Int J Health Serv 13(2):179–202. https://doi.org/10.2190/thkh-4let-txl1-d3n3

O’Connor C, Joffe H (2020) Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods 19:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

Öniş Z (2011) Power, interests and coalitions: the political economy of mass privatisation in Turkey. Third World Q 32(4):707–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.567004

Ragin CC (1992) Cases of what is a case. In: Ragin CC & Becker HS (Eds.) What is a Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry. New York: Cambridge University Press

Rose N (1998) Inventing our selves: Psychology, power, and personhood. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rose N (2007) The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press, Princeton, Oxford

Salas AA, Anderson MB (1997) Introducing information technologies into medical education: activities of AAMC. Acad Med 72(3):191–193. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199703000-00013

Saldaña J (2013) The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (Second Edition). London: SAGE Publications

Şentürk T, Terzi F, Dokmeci V et al. (2011) Privatization of health-care facilities in Istanbul. Eur Plan Stud 19(6):117–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.571056

Shiffman J (2015) Global health as a field of power relations: a response to recent commentaries. Int J Health Policy Manag 4(7):497–499. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.104

Shilling C (2012) The Body and Social Theory. SAGE Publications, London

Sointu E (2020) Challenges and a super power: how medical students understand and would improve health in AA, Anderson MB (1997) introducing information technologies into medical education: activities of AAMC. Acad Med 72(3):191–193. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199703000-00013

Sullivan D (2001) Cosmetic Surgery: The Cutting Edge of Commercial Medicine in America. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N.J

Talley HL (2012) Getting Work Done: Cosmetic Surgery as Constraint, as Commodity, as Commonplace. In: Routledge Handbook of Body Studies, ed. BS Turner, 335–347. London: Routledge

Tansley P, Fleming D, Brown T (2022) Cosmetic surgery regulation in Australia: who is to be protected—surgeons or patients? Am J Cosmet Surg 39(3):161–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/07488068221105360

Timmermans S, Berg M (2003) The practice of medical technology. Sociol Health Illn 25:97–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00342

Turner BS (2007) Medical Power and Social Knowledge. SAGE Publications, London

Ünlütürk Ulutaş Ç (2011) Türkiye’de Sağlık Emek Sürecinin Dönüşümü. Notabene Yayınları, Istanbul

Vlahos A, Bove LL (2016) Went in for Botox and left with a rhinoplasty. Mark Intell Plan 34:927–942. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-06-2015-0125

Vural İE (2017) Financialisation in health care: an Analysis of private equity fund investments in Turkey. Soc Sci Med 187:276–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.008

Weber M (1978) Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretative Sociology. University of California Press, Berkeley

Webster RC (1984) On dermatologic plastic or cosmetic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 10(7):513–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4725.1984.tb01245.x

Yılmaz V (2013) Changing Origins of Inequalities in Access to Health Care Services in Turkey: from occupational status to income. N Perspect Turk 48:55–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0896634600001886

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Ceren Tunay (Galatasaray University) for her contribution to the interviews, her contribution to the transcription of the audio recordings as well as her assistance in the coding process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors played an equally active role in in interviewing the participants, transcribing the audio recordings, coding the data, analyzing the findings, and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research project was registered with and received ethical approval from the Galatasaray University Ethical Committee on December 28, 2021, with the number E-65364513-050.06.04-17942.

Informed consent