Abstract

Background

Nodular ground-glass opacities (nGGO) are a specific type of lung adenocarcinoma. ALK rearrangements and driver mutations such as EGFR and K-ras are frequently found in all types of lung adenocarcinoma. EGFR mutations play a role in the early carcinogenesis of nGGOs, but the role of ALK rearrangement remains unknown.

Methods

We studied 217 nGGOs resected from 215 lung cancer patients. Pathology, tumor size, tumor disappearance rate, and the EGFR and ALK markers were analyzed.

Results

All but one of the resected nGGOs were adenocarcinomas. ALK rearrangements and EGFR mutations were found in 6 (2.8%) and 119 (54.8%) cases. The frequency of ALK rearrangement in nGGO was significantly lower than previously reported in adenocarcinoma. Advanced disease stage (p = 0.018) and larger tumor size (p = 0.037) were more frequent in the ALK rearrangement-positive group than in ALK rearrangement-negative patients. nGGOs with ALK rearrangements were associated with significantly higher pathologic stage and larger maximal and solid diameter in comparison to EGFR-mutated lesions.

Conclusion

ALK rearrangement is rare in lung cancer with nGGOs, but is associated with advanced stage and larger tumor size, suggesting its association with aggressive progression of lung adenocarcinoma. ALK rearrangement may not be important in early pathogenesis of nGGO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Low-dose chest computed tomography (CT) for lung cancer screening has increased the detection of solitary pulmonary nodules (SPN) not visualized on chest radiography, and has contributed to a reduction in lung cancer mortality [1]. Some of these visualized nodules are nodular ground-glass opacities (nGGOs). nGGOs on chest CT are defined as hazy, increased attenuation of the lung with preservation of bronchial and vascular margins, and are classified as pure and mixed GGOs, which contain a solid component [2].

Nodular GGOs can be found in eosinophilic lung disease, pulmonary lymphoproliferative disorder, and interstitial fibrosis, with a persistent nGGO being a possible sign of early lung cancer [3]. The natural development of nGGO follows a stepwise progression from atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) to adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS: formerly bronchioloadenocarcinoma), to microinvasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and finally to invasive adenocarcinoma (IA) [4]. However, some adenocarcinomas do not follow this pathway, manifesting as consolidation and/or solid mass, with different genetic profiles. Therefore, lung adenocarcinoma exhibits heterogeneity in pathogenesis and progression [5].

Several driver mutations have been identified in lung cancer, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and K-ras mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement. Lung cancers expressing EGFR mutations respond well to the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors [6–8]. The fusion of echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) and ALK gene by rearrangement in non-small cell lung cancer was identified [9] and developed as a target of the ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor, crizotinib [10, 11]. These biomarkers predict response to these molecular targeting agents and testing for these markers is recommended in lung cancer patients [12, 13], enabling personalized medicine for patients harboring EGFR mutations or ALK gene rearrangements. It is therefore very important to investigate the frequencies and clinical implications of these driver mutations in nGGOs, a specific type of lung adenocarcinoma.

Many studies have reported that EGFR mutations are frequent in lung cancer with nGGOs, even in precancerous lesions such as AAH [14–17]; however, the role of ALK rearrangement in nGGOs remains unknown. We analyzed patients with lung cancer with nodular GGOs to investigate the correlation between biomarker status and clinicopathological and radiologic characteristics and to determine the roles of ALK rearrangements and EGFR mutations in nGGOs.

Methods

Patients

Among the patients who underwent surgical resection of their CT-identified nGGOs between August 2008 and March 2013 at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH), we selected patients who were diagnosed with lung cancer by pathologic confirmation of the surgical specimen. Multiple nGGOs in a single patient were considered different cases of nGGO. Patient data were extracted from medical records, including those pertaining to the age at the time of surgery, sex, smoking history quantified by packs per year, tumor histology, pathologic tumor stage, and biomarker status. This study was approved and individual patient consent waived by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-1305-202-102).

Radiologic evaluation

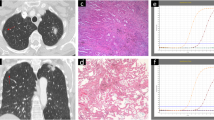

Chest CT scans were performed preoperatively in each patient. All CT images were reviewed with a pulmonary window setting (window width, 2000 HU; window level, -500 HU) and mediastinal window setting (window width 440 HU, window level 45 HU). GGOs appear in pulmonary window images of chest CT, but disappear on mediastinal window images [3]. We included all nodules that contained any amount of GGO.

To evaluate the proportion of the solid component in the nGGOs, we measured the maximum transverse diameter (Tmax) and maximum perpendicular diameter (Pmax) of both the pulmonary and mediastinal window settings (pTmax, mTmax, pPmax, mPmax) and calculated the tumor shadow disappearance rate (TDR) in all nGGOs. TDR was calculated using the following formula: TDR = 1 - (mTmax × mPmax /pTmax × pPmax) [18].

Histopathology review

Surgical specimens were reviewed by an experienced pathologist (J-H Chung) and another pathologist (H Kim). TNM classification was performed according to the Union for International Cancer Control and the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system, 7th edition [19]. In some participants, lymph node dissection was not performed because lymphatic invasion was deemed unlikely in the preoperative evaluation; these participants were considered N0 stage. Lung cancer was histologically classified as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. The majority of participants were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma and were categorized according to the 2011 International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (IASLC/ATS/ERS) classification system as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and various types of invasive adenocarcinoma (IA) [4].

Molecular analysis

We analyzed the samples for EGFR mutation and ALK rearrangements. Genomic DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. Exons 18–21 of the EGFR gene were analyzed by PCR amplification and sequencing with an ABI Prism 3100 DNA analyzer and standard protocols. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA)-mediated PCR clamping or pyrosequencing methods are more sensitive than direct sequencing (DS) for EGFR mutation detection [20], but we have found that all of these methods are appropriate when sufficient tumor cells are properly micro-dissected and analyzed within a meticulously controlled turnaround time at a single institute (SNUBH) [21]. We included only nGGO specimens resected en bloc to ensure sufficient tumor cell sampling; this is the main strength of this study, as it provided highly accurate DS detection of EGFR mutations.

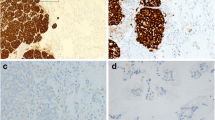

To detect ALK rearrangements, we first screened the tissues by immunohistochemistry (IHC) with monoclonal anti-ALK antibody (clone 5A4, Novocastra, 1:30, Newcastle, UK) and classified them with a four-tiered scoring system: 0, +1, +2, and +3. For cases with IHC scores of +2 or +3, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to detect ALK translocation by previously reported methods [22, 23]. Concordance between IHC and FISH is high; thus, it is appropriate to use the sensitive IHC method for screening and FISH as a standard diagnostic test to detect ALK rearrangements [24].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Numerical variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All statistical tests were two-sided, and differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

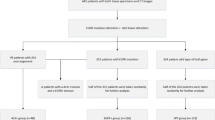

We recruited 289 patients who underwent surgical treatment for nGGOs from August 2009 to March 2013 at SNUBH. After pathologic confirmation of the surgical specimens, nine patients were excluded with diagnoses of non-cancerous lung conditions, including three interstitial fibroses, two lymphoplasma cell infiltrations, two chronic inflammations, one anthracofibrotic nodule, and one AAH. The remaining 280 nGGOs in 261 patients were considered lung cancer, including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenosquamous carcinoma. We excluded 63 nGGOs in 46 patients for whom EGFR and/or ALK status was unavailable. Finally, 217 nGGO lesions in 215 patients were enrolled. Two patients had multiple nGGO lesions, which were tested for biomarker status. All nodules were diagnosed as adenocarcinoma, except one, which was identified as adenosquamous carcinoma.

Pathologic classification of GGO nodules

Pathologic findings of 217 nGGOs were classified according to the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification. Numbers of AIS, MIA, and IA were 15, 16, and 185, respectively, and there was one adenosquamous carcinoma. Acinar predominant adenocarcinoma was the most frequent type in nGGOs. Seven solid predominant adenocarcinomas and five invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas also presented as nodules with GGOs. Six ALK rearrangement-positive (ALK-positive) nGGOs were invasive adenocarcinomas, whereas 11.8% (14 out of 119) of EGFR mutation-positive nGGOs were pre-invasive or minimally invasive adenocarcinomas. Subtypes of invasive adenocarcinoma revealed no statistical difference between ALK rearrangement and EGFR mutation-positive nGGOs (Table 1).

Analysis of ALK- and EGFR mutation-positive nodules

FISH identified ALK rearrangements in six lesions (2.8%) and EGFR mutations in 119 lesions (54.8%). These driver gene mutations were mutually exclusive in the examined nGGOs.

ALK-positive GGO nodules

Histopathology revealed that patients with ALK-positive nGGOs exhibited more advanced disease stages according to the AJCC, 7th edition (p = 0.018) (Table 2). ALK-positive nodules were significantly larger than ALK-negative nodules (p = 0.037). The solid proportion of ALK-positive nodules was also significantly larger than that of ALK-negative nodules (p = 0.039). All ALK-positive nodules were IA according to the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification; three nGGOs were acinar predominant subtypes, one was the solid subtype, one was the lepidic subtype, and one was the papillary predominant subtype (Table 1). Three nodules showed cribriform features and one nodule showed a signet ring cell pattern.

EGFR mutation-positive GGO nodules

EGFR mutations were more frequent in women (p = 0.004) and in non-smokers or light smokers (p < 0.001). nGGOs with EGFR mutations did not significantly non-mutated lesions in terms of nodule size, solid proportion, nodal involvement, pathologic stage, and histologic invasiveness (Table 3). Among nGGO lesions with EGFR mutations, 56 nodules had a point mutation in exon 21 (L858R mutation in 54, L861Q in 1, and G863C in 1). Patients with EGFR mutations in exon 21 were older than patients with wild-type EGFR lesions (p = 0.034), were more likely to be non-smokers or light smokers (p = 0.002), and were more frequently women (p = 0.001). Patients with EGFR mutations in exons 19 or 20 showed no significant clinicopathological and radiologic differences in comparison to those without EGFR mutations (Table 4).

Comparison between groups with distinct molecular biomarkers

No significant demographic differences were found between the two molecular biomarker groups. Interestingly, nGGOs with ALK rearrangement were associated with significantly higher pathologic stage and larger maximal and solid diameter in comparison to nGGO lesions with EGFR mutation, but not in TDR. All ALK-positive nodules were classified as IA, but this trend was not significant due to the relatively small sample size (Table 5).

Comparison of EGFR mutation and ALK rearrangement rate in GGO nodules to previous studies of a large cohort of adenocarcinomas

The prevalence of EGFR and ALK mutations in GGO nodules in this study was compared to previous reports of adenocarcinoma of all types. As summarized in Table 6 the ALK rearrangement rate (2.8%) in this study was quite low. We previously reported an ALK rearrangement rate of 6.8% in all types of adenocarcinoma [23]. Other reports from Korean institutes showed higher rates of ALK rearrangement [5.4% [25] and 20.4% [26]]; however, no significant difference was found in EGFR mutation rate.

Discussion

Lung cancer, in its early stage, can present as nGGOs on chest CT. Lung adenocarcinoma with growth patterns involving the alveolar septum and a relative lack of acinar filling shows GGOs on chest CT, and a high GGO proportion is correlated with good prognosis [27]. Pathology of GGO nodules has shown that the proportion of GGO in nodular adenocarcinomas decreases through the AAH-AIS-MIA-IA pattern of progression [28], and that GGO nodules must undergo in situ changes, since AIS (formerly called BAC) and precancerous lesions such as AAH correspond to pure GGO [15].

The clinicopathologic, radiologic, and molecular biological characteristics of nGGOs are important for our understanding of the mechanism of carcinogenesis and for predicting the chemotherapeutic response. Since the introduction of molecular targeting agents, many groups have studied the EGFR mutation status of nGGOs, but there is little data on ALK rearrangements in nGGOs. EGFR mutations are frequently found in the early stages of nGGO, such as in AAH and AIS, and play an important role in the pathogenesis of adenocarcinoma with GGO patterns. However, the role of ALK rearrangement, another potent driver mutation in adenocarcinoma, has not been described in GGO nodules.

In this study, we investigated the frequencies and clinicopathological characteristics of driver mutations, focusing on ALK rearrangement in resected adenocarcinoma with GGO patterns. To our knowledge, this is the largest comprehensive analysis of lung cancer presenting as GGO nodules. We included lung cancer nodules exhibiting any amount of GGO regardless of its size, thereby investigating the molecular biomarker status of lung cancer at early stages.

Adenocarcinoma with ALK rearrangement is usually found in younger, female patients who have light to no smoking history, and has been reported to have acinar, papillary, cribriform, and signet-ring patterns. The radiological characteristics of lung cancer with ALK rearrangement have hardly been studied, and there is a lack of data concerning the role of ALK rearrangement in nGGO lesions. In one study, Fukui et al. reported that no GGO nodules were found in patients with ALK rearrangement while 50% of adenocarcinomas that did not have ALK rearrangement also had GGO nodules and also EML4-ALK-positive tumors mainly exhibited a solid pattern on CT [29].

In this study, the proportion of ALK-positive nGGO lesions was significantly lower (2.8%) than that obtained in previous studies of a large cohort of adenocarcinomas (3.9-20.4%) (Table 6) [23, 25, 26, 29–32], and was significantly lower than the 6.8% of 395 resected adenocarcinoma patients in our previous study, which included all types of curatively resected adenocarcinoma [23]. This could be indirect evidence of the lower incidence of ALK rearrangements in adenocarcinomas with GGO patterns compared to adenocarcinomas of all types.

It is well known that ALK-positive adenocarcinoma is likely to present a signet-ring cell or cribriform pattern and abundant mucin production on histological analysis [33, 34]: ALK-positive lesions are observed as a solid, rather than a GGO, nodule [29, 35, 36]. This explains the low proportion of ALK-positive patients in this study, which focuses on nGGOs. Fukui et al. studied the radiologic characteristics of 28 ALK-positive adenocarcinomas and revealed no GGO portion [29] and another report on CT characteristics of ALK rearranged advanced NSCLC from Japan also report low frequency of ALK rearrangement (one among 36 cases) [36], consistent with our findings.

We revealed that maximal diameters and the solid portion of nGGOs with ALK rearrangement were significantly larger than were those without ALK rearrangement. All nGGOs with ALK rearrangement were IA (invasive adenocarcinoma) with acinar predominant subtypes (n = 3) and three with cribriform pattern. Patients with ALK-positive lesions showed more advanced pathologic stages than those with EGFR-positive GGOs. Therefore, we suggest ALK rearrangement is associated with cellular and histological type as well as clinical aggressiveness.

Several studies have revealed that adenocarcinomas with ALK rearrangement have more lymph node metastases [23, 25]. Combined with the radiological characteristics discussed above, the ALK-positive adenocarcinoma seems not to follow the stepwise carcinogenesis pattern of AAH-AIS-MIA-IA, but to grow rapidly and bypass the phase of lepidic growth. This assumption is consistent with the histological analysis of ALK-positive adenocarcinomas showing lower frequencies of lepidic growth and AAH/BAC (AIS) in the background of ALK-positive lung adenocarcinomas [35].

Distinct subsets of adenocarcinoma with morphologic differentiation to type II pneumocytes, Clara cells, or non-ciliated bronchioles are thought to originate from the terminal respiratory unit (TRU), and EGFR mutation is involved with early-stage carcinogenesis of TRU-type adenocarcinoma [5, 37]; nGGOs appear to be another marker of TRU-type adenocarcinoma [5].

Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) is a marker of TRU-type adenocarcinoma [37, 38], and two studies concerning 11 and 12 ALK-positive patients each revealed TTF-1 positivity in all ALK-positive adenocarcinomas [26, 39]. This finding suggests that this subtype of adenocarcinoma may have TRU-origin histogenesis [39]. However, the low proportion of GGO with ALK rearrangement and the advanced stage in ALK-positive nGGOs found in this study indicates that it is still possible that this subtype may not follow a process of TRU origin. Further pathologic analysis of morphological characteristics is required.

Because the prevalence of adenocarcinoma with ALK rearrangement is low compared to EGFR mutation, studies investigating various characteristics of ALK-positive lung cancer do not gather enough participants to yield consistent results. Previous studies on a large, unselected population of adenocarcinoma with ALK rearrangement reported that patients with ALK-positive lung cancer were younger [23, 29, 30, 32], female [23, 25, 40], and light or non-smokers [23, 25, 29, 30, 32, 40, 41]. We previously reported that ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinomas of all radiologic types showed higher stage at diagnosis and more solid pattern, were more cribriform, and had a closer relationship with adjacent bronchioles [42] and more frequently positive bronchoscopic findings than EGFR-positive lung adenocarcinoma [43], which suggested more proximal origin of ALK rearranged lung adenocarcinoma than EGFR-positive adenocarcinoma. These findings were consistent with low frequency of ALK rearrangement in nGGOs which presented in peripheral location.

We found no correlation between age, sex, smoking status, and ALK positivity, probably due to the small number of ALK-positive patients and the weak representation of adenocarcinoma, since we enrolled only patients with nGGOs.

We found that EGFR mutation was associated with female, never/light smokers, as expected [44]. The frequency of EGFR mutation in nGGOs in this study was 54.8%, which was relatively high in comparison to other, large cohorts of adenocarcinoma [25, 45–50] (Table 6). However, we could not predict EGFR mutation status by the GGO proportion of nodules or tumor size. EGFR mutation status was not associated with pathologic stage, nodal involvement, or histologic invasiveness.

It is interesting that after stratifying EGFR mutations in exons 19, 20, and 21, only the mutation in exon 21 (mostly L858R) correlated with female gender and never/light smoking status. This result is consistent with other studies of the characteristics of adenocarcinoma and EGFR mutation type [51, 52]. The association between EGFR and female non- or light smoker may be limited to EGFR mutation in exon 21.

According to large cohort studies, EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements are mutually exclusive. However, several cases of co-incident EGFR mutation and ALK rearrangement have been reported, most of which demonstrated good response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors [32]. In our study, which recruited participants at the early stage of adenocarcinoma, these molecular biomarkers were mutually exclusive. It is thought that they act through different mechanisms in early carcinogenesis.

The major strength of study is that it is the largest cohort concerning lung cancer with nGGOs. All nodules were resected by curative surgery, which reinforced the accuracy of pathologic and molecular diagnoses of the surgical specimens. Although we collected enough GGO nodules with EGFR mutations in exons 19 and 21, we could not collect sufficient numbers of samples with ALK rearrangement due to the inherent limitation that adenocarcinoma with ALK rearrangement tends to present as solid nodules in chest CT.

Conclusions

ALK rearrangement is rare in lung adenocarcinoma presenting as nGGOs and is associated with a more advanced stage and larger tumor size, suggesting a distinct origin and an aggressive nature in the progression of lung adenocarcinoma. ALK rearrangement may not play an important role in the early pathogenesis of nGGO. It is important to understand the clinicopathological characteristics of nGGOs associated with each driver mutation, as well as their radiologic correlations, when individualizing lung cancer treatments with molecular-targeted therapies.

Abbreviations

- EGFR :

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ALK :

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- nGGO:

-

Nodular ground glass opacity

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- SPN:

-

Solitary pulmonary nodule

- AAH:

-

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia

- AIS:

-

Adenocarcinoma in situ, MIA, microinvasive adenocarcinoma

- IA:

-

Invasive adenocarcinoma

- TDR:

-

Tumor shadow disappearance rate

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- FISH:

-

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- TRU:

-

Terminal respiratory unit

- TTF-1:

-

Thyroid transcription factor-1.

References

Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks J: Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011, 365 (5): 395-409.

Godoy MC, Naidich DP: Subsolid Pulmonary Nodules and the Spectrum of Peripheral Adenocarcinomas of the Lung: Recommended Interim Guidelines for Assessment and Management. Radiology. 2009, 253 (3): 606-622. 10.1148/radiol.2533090179.

Lee HY, Lee KS: Ground-glass opacity nodules: histopathology, imaging evaluation, and clinical implications. J Thorac Imaging. 2011, 26 (2): 106-118. 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181fbaa64.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, Beer DG, Powell CA, Riely GJ, Van Schil PE, Garg K, Austin JH, Asamura H, Rusch VW, Hirsch FR, Scagliotti G, Mitsudomi T, Huber RM, Ishikawa Y, Jett J, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Sculier JP, Takahashi T, Tsuboi M, Vansteenkiste J, Wistuba I, Yang PC, Aberle D, Brambilla C, Flieder D, et al: International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011, 6 (2): 244-285. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221.

Takeuchi T, Tomida S, Yatabe Y, Kosaka T, Osada H, Yanagisawa K, Mitsudomi T, Takahashi T: Expression profile-defined classification of lung adenocarcinoma shows close relationship with underlying major genetic changes and clinicopathologic behaviors. J Thorac Oncol. 2006, 24 (11): 1679-1688.

Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, Gemma A, Harada M, Yoshizawa H, Kinoshita I: Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non–small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010, 362 (25): 2380-2388. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530.

Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, Seto T, Satouchi M, Tada H, Hirashima T: Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11 (2): 121-128. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X.

Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ, Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S, Lu S, Zhang L, Hu C, Luo Y, Chen L, Ye M, Huang J, Zhi X, Zhang Y, Xiu Q, Ma J, Zhang L, You C: Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12 (8): 735-742. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X.

Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, Fujiwara S-i, Watanabe H, Kurashina K, Hatanaka H: Identification of the transforming EML4–ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007, 448 (7153): 561-566. 10.1038/nature05945.

Kwak EL, Bang Y-J, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, Ou S-HI, Dezube BJ, Jänne PA, Costa DB: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363 (18): 1693-1703. 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448.

Shaw AT, Kim D-W, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crinó L, Ahn M-J, De Pas T, Besse B, Solomon BJ, Blackhall F: Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368 (25): 2385-2394. 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886.

Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Borghaei H, Chang AC, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, D’Amico TA, Demmy TL, Ganti AKP, Govindan R: Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2012, 10 (10): 1236-1271.

Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, Jenkins RB, Kwiatkowski DJ, Saldivar J-S, Squire J: Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2013, 15 (4): 415-453. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.03.001.

Aoki T, Hanamiya M, Uramoto H, Hisaoka M, Yamashita Y, Korogi Y: Adenocarcinomas with Predominant Ground-Glass Opacity: Correlation of Morphology and Molecular Biomarkers. Radiology. 2012, 264 (2): 590-596. 10.1148/radiol.12111337.

Chung J-H, Choe G, Jheon S, Sung S-W, Kim TJ, Lee KW, Lee JH, Lee C-T: Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation and pathologic-radiologic correlation between multiple lung nodules with ground-glass opacity differentiates multicentric origin from intrapulmonary spread. J Thorac Oncol. 2009, 4 (12): 1490-1495. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181bc9731.

Yoshida Y, Kokubu A, Suzuki K, Kuribayashi H, Tsuta K, Matsuno Y, Kusumoto M, Kanai Y, Asamura H, Hirohashi S: Molecular markers and changes of computed tomography appearance in lung adenocarcinoma with ground-glass opacity. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007, 37 (12): 907-912. 10.1093/jjco/hym139.

Yano M, Sasaki H, Kobayashi Y, Yukiue H, Haneda H, Suzuki E, Endo K, Kawano O, Hara M, Fujii Y: Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation and computed tomographic findings in peripheral pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2006, 1 (5): 413-416. 10.1097/01243894-200606000-00006.

Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, Uchino K, Tsubota N: Discrepancy of computed tomographic image between lung and mediastinal windows as a prognostic implication in small lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003, 76 (6): 1828-1832. 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01077-4.

Goldstraw P: The 7th Edition of TNM in Lung Cancer: what now?. J Thorac Oncol. 2009, 4 (6): 671-673. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819e7814.

Kim HJ, Lee KY, Kim Y-C, Kim K-S, Lee SY, Jang TW, Lee MK, Shin K-C, Lee GH, Lee JC: Detection and comparison of peptide nucleic acid-mediated real-time polymerase chain reaction clamping and direct gene sequencing for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012, 75 (3): 321-325. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.08.005.

Lee HJ, Xu X, Kim H, Jin Y, Sun P, Kim JE, Chung J-H: Comparison of Direct Sequencing, PNA Clamping-Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction, and Pyrosequencing Methods for the Detection of EGFR Mutations in Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma and the Correlation with Clinical Responses to EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor. Korean J Pathol. 2013, 47 (1): 52-60. 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.1.52.

Paik JH, Choe G, Kim H, Choe J-Y, Lee HJ, Lee C-T, Lee JS, Jheon S, Chung J-H: Screening of anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement by immunohistochemistry in non-small cell lung cancer: correlation with fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Thorac Oncol. 2011, 6 (3): 466-472. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820b82e8.

Paik JH, Choi C-M, Kim H, Jang SJ, Choe G, Kim DK, Kim HJ, Yoon H, Lee C-T, Jheon S: Clinicopathologic implication of ALK rearrangement in surgically resected lung cancer: a proposal of diagnostic algorithm for ALK-rearranged adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2012, 76 (3): 403-409. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.008.

Kim H, Shim HS, Kim L, Kim T-J, Kwon KY, Lee GK, Chung J-H: Guideline Recommendations for Testing of ALK Gene Rearrangement in Lung Cancer: a Proposal of the Korean Cardiopulmonary Pathology Study Group. Korean J Pathol. 2014, 48: 1-9. 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2014.48.1.1.

Choi H, Paeng JC, Kim D-W, Lee JK, Park CM, Kang KW, Chung J-K, Lee DS: Metabolic and metastatic characteristics of ALK–rearranged lung adenocarcinoma on FDG PET/CT. Lung Cancer. 2013, 79 (3): 242-247. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.11.021.

Koh Y, Kim D-W, Kim TM, Lee S-H, Jeon YK, Chung DH, Kim Y-W, Heo DS, Kim W-H, Bang Y-J: Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive advanced pulmonary adenocarcinoma: suggestion for an effective screening strategy for these tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2011, 6 (5): 905-912. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182111461.

Aoki T, Tomoda Y, Watanabe H, Nakata H, Kasai T, Hashimoto H, Kodate M, Osaki T, Yasumoto K: Peripheral Lung Adenocarcinoma: Correlation of Thin-Section CT Findings with Histologic Prognostic Factors and Survival. Radiology. 2001, 220 (3): 803-809. 10.1148/radiol.2203001701.

Takashima S, Maruyama Y, Hasegawa M, Yamanda T, Honda T, Kadoya M, Sone S: CT findings and progression of small peripheral lung neoplasms having a replacement growth pattern. Am J Roentgenol. 2003, 180 (3): 817-826. 10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800817.

Fukui T, Yatabe Y, Kobayashi Y, Tomizawa K, Ito S, Hatooka S, Matsuo K, Mitsudomi T: Clinicoradiologic characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinoma harboring EML4-ALK fusion oncogene. Lung Cancer. 2012, 77 (2): 319-325. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.03.013.

Rodig SJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Dacic S, Yeap BY, Shaw A, Barletta JA, Stubbs H, Law K, Lindeman N, Mark E: Unique clinicopathologic features characterize ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma in the western population. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15 (16): 5216-5223. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0802.

Takeuchi K, Soda M, Togashi Y, Suzuki R, Sakata S, Hatano S, Asaka R, Hamanaka W, Ninomiya H, Uehara H: RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer. Nat Med. 2012, 18 (3): 378-381. 10.1038/nm.2658.

Wang Z, Zhang X, Bai H, Zhao J, Zhuo M, An T, Duan J, Yang L, Wu M, Wang S: EML4-ALK rearrangement and its clinical significance in Chinese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology. 2012, 83 (5): 248-256. 10.1159/000341381.

Pillai RN, Ramalingam SS: The Biology and Clinical Features of Non–small Cell Lung Cancers with EML4-ALK Translocation. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012, 14 (2): 105-110. 10.1007/s11912-012-0213-4.

Jokoji R, Yamasaki T, Minami S, Komuta K, Sakamaki Y, Takeuchi K, Tsujimoto M: Combination of morphological feature analysis and immunohistochemistry is useful for screening of EML4-ALK-positive lung adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2010, 63 (12): 1066-1070. 10.1136/jcp.2010.081166.

Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Nakamura H, Kohno T, Takahashi F, Asamura H, Sekine I, Fukayama M, Shibata T, Furuta K: Comprehensive histologic analysis of ALK-rearranged lung carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011, 35 (8): 1226-1234. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182233e06.

Park J, Yamaura H, Yatabe Y, Hosoda W, Kondo C, Shimizu J, Horio Y, Yoshida K, Tanaka K, Oguri T, Kobayashi Y, Hida H: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangements in patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: CT characteristics and response to chemotherapy. Cancer Med. 2014, 3 (1): 118-123. 10.1002/cam4.172.

Yatabe Y, Kosaka T, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T: EGFR mutation is specific for terminal respiratory unit type adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005, 29 (5): 633-639. 10.1097/01.pas.0000157935.28066.35.

Park WY, Kim MH, Shin DH, Lee JH, Choi KU, Kim JY, Park DY, Lee CH, Sol MY: Ciliated adenocarcinomas of the lung: a tumor of non-terminal respiratory unit origin. Mod Pathol. 2012, 25 (9): 1265-1274. 10.1038/modpathol.2012.76.

Inamura K, Takeuchi K, Togashi Y, Hatano S, Ninomiya H, Motoi N, Mun M-y, Sakao Y, Okumura S, Nakagawa K: EML4-ALK lung cancers are characterized by rare other mutations, a TTF-1 cell lineage, an acinar histology, and young onset. Mod Pathol. 2009, 22 (4): 508-515. 10.1038/modpathol.2009.2.

Li Y, Li Y, Yang T, Wei S, Wang J, Wang M, Wang Y, Zhou Q, Liu H, Chen J: Clinical Significance of EML4-ALK Fusion Gene and Association with EGFR and KRAS Gene Mutations in 208 Chinese Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (1): e52093-10.1371/journal.pone.0052093.

Takahashi T, Kobayashi M, Yoshizawa A, Menju T, Nakayama E: Clinicopathologic features of non-small-cell lung cancer with EML4–ALK fusion gene. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010, 17 (3): 889-897. 10.1245/s10434-009-0808-7.

Kim H, Jang SJ, Chung DH, Yoo SB, Sun P, Jin Y, Nam KH, Paik JH, Chung JH: A comprehensive comparative analysis of the histomorphological features of ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma based on driver oncogene mutations: frequent expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers than other genotype. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (10): e76999-10.1371/journal.pone.0076999.

Kang HJ, Lim HJ, Park JS, Cho YJ, Yoon HI, Chung JH, Lee JH, Lee CT: Comparison of clinical characteristics between patients with ALK-positive and EGFR-positive lung adenocarcinoma. Respir Med. 2014, 108 (2): 388-394. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.020.

Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG: Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non–small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004, 350 (21): 2129-2139. 10.1056/NEJMoa040938.

Huang Y-s, Yang J-j, Zhang X-c, Yang X-n, Huang Y-j, Xu C-r, Zhou Q, Wang Z, Su J, Wu Y: Impact of smoking status and pathologic type on epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Chin Med J. 2011, 124 (16): 2457-2460.

Kim HR, Ahn JR, Lee JG, Bang DH, Ha S-J, Hong YK, Kim SM, Nam KC, Rha SY, Soo RA: The Impact of Cigarette Smoking on the Frequency of and Qualitative Differences in KRAS Mutations in Korean Patients with Lung Adenocarcinoma. Yonsei Med J. 2013, 54 (4): 865-874. 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.4.865.

Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Kuwano H, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T: Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2004, 64 (24): 8919-8923. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2818.

Liam C-K, Wahid MIA, Rajadurai P, Cheah Y-K, Ng TS-Y: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma in Malaysian Patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2013, 8 (6): 766-772. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828b5228.

Sun P-L, Seol H, Lee HJ, Yoo SB, Kim H, Xu X, Jheon S, Lee C-T, Lee J-S, Chung J-H: High Incidence of EGFR Mutations in Korean Men Smokers with No Intratumoral Heterogeneity of Lung Adenocarcinomas: Correlation with Histologic Subtypes, EGFR/TTF-1 Expressions, and Clinical Features. J Thorac Oncol. 2012, 7 (2): 323-330. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182381515.

Uramoto H, So T, Nagata Y, Kuroda K, Shigematsu Y, Baba T, So T, Takenoyama M, Hanagiri T, Yasumoto K: Correlation between HLA alleles and EGFR mutation in Japanese patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2010, 5 (8): 1136-1142. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e0b993.

Hsu K-H, Chen K-C, Yang T-Y, Yeh Y-C, Chou T-Y, Chen H-Y, Tsai C-R, Chen C-Y, Hsu C-P, Hsia J-Y: Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status in stage I lung adenocarcinoma with different image patterns. J Thorac Oncol. 2011, 6 (6): 1066-1072. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821667b0.

Lee H-J, Kim YT, Kang CH, Zhao B, Tan Y, Schwartz LH, Persigehl T, Jeon YK, Chung DH: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation in Lung Adenocarcinomas: Relationship with CT Characteristics and Histologic Subtypes. Radiology. 2013, 268 (1): 254-264. 10.1148/radiol.13112553.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/312/prepub

Acknowledgement

We also appreciated CS Leem for managing data base of cancer registry of SNUBH. We thank Editage, Korea for providing proofreading and medical editing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing of interest

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

SJK and CTL had full access to data, writing, and responsibility for the manuscript. YJL, JSP, YJC, HIY, and JHL assisted with recruitment and critical reading of the manuscript. JHC examined the pathology and analyzed EGFR and ALK status. HK reviewed the pathologic specimen. TJK and KWL analyzed radiological characteristics of nGGOs. KK and SJ performed surgical resection of nGGOs. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, SJ., Lee, Y.J., Park, J.S. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangements in lung cancer with nodular ground-glass opacity. BMC Cancer 14, 312 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-312

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-312