Abstract

Background

The use of structured curricula for minimally invasive surgery training is becoming increasingly popular. However, many laparoscopic training programs still use basic skills and isolated task training, despite increasing evidence to support the use of training models with higher functional resemblance, such as whole procedural modules. In contrast to basic skills training, procedural training involves several cognitive skills such as elements of planning, movement integration, and how to avoid adverse events. The objective of this trial is to investigate the specificity of procedural practice in laparoscopic simulator training.

Methods/Design

A randomised single-centre educational superiority trial. Participants are 96 surgical novices (medical students) without prior laparoscopic experience. Participants start by practicing a series of basic skills tasks to a predefined proficiency level on a virtual reality laparoscopy simulator. Upon reaching proficiency, the participants are randomised to either the intervention group, which practices two procedures (an appendectomy followed by a salpingectomy) or to the control group, practicing only one procedure (a salpingectomy) on the simulator. 1:1 central randomisation is used and participants are stratified by sex and time to complete the basic skills. Data collection is done at a surgical skills centre.

The primary outcome is the number of repetitions required to reach a predefined proficiency level on the salpingectomy module. The secondary outcome is the total training time to proficiency. The improvement in motor skills and effect on cognitive load are also explored.

Discussion

The results of this trial might provide new knowledge on how the technical part of surgical training curricula should be comprised in the future. To examine the specificity of practice in procedural simulator training is of great importance in order to develop more comprehensive surgical curricula.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02069951

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Laparoscopic simulation training has become important in the acquisition of laparoscopic skills before operating on patients. Skills are ideally acquired through a structured curriculum using both feedback and predefined training goals [1]. Although there is a consensus that the curriculum should include a technical skills component, few studies have been conducted on exactly which technical skills should be included [2, 3]. Currently, there are only a few procedural modules for laparoscopy with solid evidence of the validity of metrics, including definition of proficiency levels [4]. In addition, many training curricula focus on isolated task training and do not incorporate procedural training [5]. Complex skills such as procedural training differ from isolated task training, as they involve more cognitive elements like planning, decision-making, and integration of isolated skills. When learning more complex skills in laparoscopic surgery, practicing only basic skills has not proven to be an effective strategy [6].

However, some of the elements practiced during procedural training may be transferable between different procedures. Thus, it is relevant to examine if repeated procedural simulator practice is relevant, which in turn will help develop the most sustainable curricula for minimally invasive surgical skills. Previous research have shown contradictory results; while some studies have found that laparoscopic skills are generalisable, other studies have found a high degree of task specificity for procedural training [7–9].

The objective of this trial is to examine the specificity of proficiency-based procedural simulator training and to examine transferability between two different procedural modules. Our hypothesis is that the same cognitive processes are utilised in the practicing of different complex laparoscopic tasks, like procedural training, and therefore these processes are transferable between different tasks.

Methods and design

Design

The trial is a randomised single-centre educational superiority trial.

Participants

Participants are medical students recruited through an invitation distributed to student associations for general surgery and gynaecology and through a student newspaper. Inclusion criteria are: (1) enrolled at the Faculty of Health Science at the University of Copenhagen, (2) a bachelor’s degree in medicine, and (3) signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria are: (1) having previously participated in a trial involving laparoscopic training, (2) having performed laparoscopic surgery (>0 procedures), and (3) not speaking Danish at a conversational level. Every participant receives a unique trial identification number upon enrolment.

Intervention

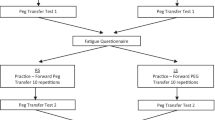

Participants are invited to participate in an introductory meeting in which information on the trial is given. All participants are informed verbally and in writing by the principal investigator before giving written informed consent. Participants can book three-hour training sessions through an online booking system; only one training session per day is permitted. Training sessions take place at the surgical skills centre at Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen. At the first training session, the participants are introduced to the simulator equipment by the principal investigator, and instructed on how to use it. The principal investigator supervises all training sessions and observes that the participants use both correct operating technique and handle instruments correctly. Participants start by practicing six basic skills tasks for isolated skills until they reach a predefined proficiency level for all tasks. The basic skills tasks do not have to be passed in any specific order. After each attempt, the simulator shows the participants automated feedback on each of the different measured parameters. Further more, the principal investigator provides feedback on request. The performance parameters and the predefined proficiency levels for each basic skill modules are listed in Table 1. Upon reaching proficiency for all tasks, the participants are randomised. Those randomised to the intervention group practice two procedures on the simulator to a predefined proficiency level: a laparoscopic appendectomy performed using endoloop technique (procedure A) and followed by a laparoscopic salpingectomy due to an ectopic pregnancy (procedure B). The control group only practices procedure B, Figure 1. The performance parameters and requirements for the predefined proficiency levels for procedures A and B are listed in Table 2. When practicing the two procedural modules, instructor feedback is provided after the first and tenth repetition [10]. The feedback is standardised and focuses on correct technique, instrument handling, and use of diathermy. For both the basic skills modules and the procedural modules, written instructions and video examples of the tasks are available for the participants and can be used at their own discretion. The predefined proficiency level for each module is reached when all of the requirements for the performance parameters is met simultaneously. This has to be archived for two attempts within five consecutive repetitions. The predefined proficiency levels are based on previous studies by the research group [1, 11]. Each participant is expected to use between six and twelve hours within a period of two months to complete the training program.

Simulation equipment

Four simulator stations, each with the virtual reality simulator LapSim® (Software Version 2013) from Surgical Science (Gothenburg, Sweden), are used. The station’s height is adjustable and consists of a 27” monitor, which is attached to a gaming computer with a pair of Simball 4D Joystick from G-coder Systems (Gothenburg, Sweden). All computers are connected to a local server containing an electronic database storing the data generated after each attempt on the simulator. Training stations are separated using wall dividers and there is a pair of noise cancelling Bose Quiet Comfort III earphones at each station. This reduces possible distractions and prevents participants from observing and interacting with each other during practice sessions.

Randomisation

Copenhagen Trial Unit is responsible for a central computerised 1:1 randomisation. The allocation sequence is computer-generated, with a varying block size kept concealed from the investigator. A web-based response system is used to allocate participants after they have completed the basic skills modules (see Intervention). The stratification variables are sex (male/female) and training time to reach proficiency for all basic tasks (less than or equal to two hours/more than two hours).

Blinding

Because of the nature of the intervention, it is not possible to blind the participants and the principal investigator to the allocation of the participants. Data entry is performed independently, without the involvement of the principal investigator. All forms are entered in a database using double data entry by external personal. A person other than the principal investigator, who is familiar with the simulator equipment, performs external data monitoring of the simulator data during the trial. The statistical analysis is blinded and the statistician is not aware of the intervention allocation of participants during the analysis; this is done with the two groups, coded as X and Y. After the analysis, two conclusions are drawn by the steering committee with the blinding intact; one conclusion assuming X is in the intervention group and Y is in the control group, and one conclusion assuming the opposite. Only thereafter is the randomisation code broken.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the number of repetitions necessary to reach the predefined proficiency level for procedure B. The secondary outcome is the total effective training time on the simulator for procedure B (in minutes). Exploratory outcomes are the cognitive load and parameters for movements, and time after the first attempt on procedure B. The cognitive load is measured using the Subjective Mental Effort Question (SMEQ), which is a cognitive workload questionnaire designed to allow individuals to rate the amount of effort invested during a task [12]. The questionnaire consists of a scale of 0 to 150 points, with nine scale markers with verbal statements ranging from ‘not at all hard to do’ to ‘tremendously hard to do’. The SMEQ has been previously been published and used in combination with simulator training [13, 14]. The SMEQ is filled out after the first attempt on procedure B. The performance parameters for movement (total path length for both right and left hand and total angular path for right and left hand) and time for the first attempt on procedure B are compared to assess the improvement in motor skills.

Ethical considerations

The trial complies with the Helsinki Declaration on biomedical research and has been submitted to the Regional Scientific Ethics Committee, which found that in accordance with Danish regulations, ethical approval is not required for carrying out the trial (H-4-2013-FSP). The trial is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02069951). The trial complies with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for randomised trials (Figure 1) [15]. All participants receive verbal and written information on the trial before inclusion; participation is voluntary and participants do not receive any gifts or monetary compensation. All participants can withdraw from the trial at any time with no consequences to their future studies; participants are asked about their reasons for withdrawal but are not obliged to answer. All data is kept confidential and published anonymously.

Sample size determination

Based on a previous study we expect the control group to take approximately 30 repetitions to reach the proficiency level, with a standard deviation of 15 [10]. A minimal difference of 10 repetitions between the two groups is deemed clinically relevant, meaning that the intervention group is expected to take approximately 20 repetitions to reach proficiency. The standard deviation is assumed to be equal in both groups. With alpha set to 0.05 and beta to 0.10 we need 48 participants in each group, totalling 96 participants.

Statistical analysis

Data will be analysed using SPSS (Chicago IL, version 20.0), SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, version 9.4) and the statistical software package R (version 3.0.3). A two-sided significance level of 0.05 will be used. The primary and secondary outcomes will be compared using the normal linear multivariable model, adjusting for the two stratification variables. If the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance are not sufficiently fulfilled, the outcome data will be transformed. If the assumptions cannot be met by transformation either robust regression, weighted least squares, or bootstrap methods will be applied. If none of these methods seem to give an adequate description of the data, the intervention and control group will be compared using the van Elteren test, and a non-parametric estimate of the confidence interval of the intervention effect will be obtained by bootstrapping [16, 17]. The p-values obtained for secondary and exploratory outcomes will be adjusted for multiplicity using the Benjamin-Hochberg procedure [18].

Missing data

All analyses are performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. In case of less than 5 percent missing data for the randomised participants for primary and secondary outcome, a complete case analysis will be performed. In case of more than 5 percent missing data, a sensitivity analysis will be performed using a best-worst and worst-case scenario imputation. If these analyses allow for the same conclusion as the complete case analysis, the complete case analysis will be reported. If the best-worst and worst-best case analyses result in a different conclusion than the complete case analysis, multiple imputations will be performed. The multiple imputations will be based on the fully observed variables (that is, sex, intervention, SMEQ-score).

Discussion

Deliberate practice and task specificity

The presented trial design examines the transferability of skills between different procedural modules on a laparoscopic virtual reality simulator. A previous trial has found that training a basic skill is not an effective strategy for learning a more complex laparoscopic task [6], though most surgical training programs use only isolated or basic skills training [5, 19, 20]. Limited research has investigated which tasks and technical skills should be included in comprehensive minimally invasive surgical curricula [2]. Previous studies have focused on the importance of fidelity for transfer to a clinical setting or transferability between basic and more complex tasks. So far, no studies have examined the transferability between two complex tasks in laparoscopic training; thus, it is unclear whether it is necessary to practice more than one procedural module on a simulator. It is possible that the cognitive aspects of procedural training like instrument coordination, procedural planning, and error recognition could be taught using procedural modules that are different from the procedure that the trainees are supposed to perform in clinical practice. This concept is known as positive transfer, in which a previously practiced skill positively influences the acquisition of a new skill. The transfer effect can be caused by either similarities in the cognitive processes used to perform the skill or because the two skills contain many identical elements [21]. According to the specificity of practice hypothesis and Ericsson’s framework for deliberate practice the use of task specific training is important [21, 22]. This includes using both task-specific performance goals and a training setup resembling where the practiced skills is going to be used [23]. This is consistent with two randomised trials’ findings that using a model with higher functional resemblance may yield a better end result and increase transferability [7, 24, 25]. The same observation has been made in sports; for example, different types of throws exist in badminton and there may be a high degree of specificity when learning a specific skill or type of movement [21, 26, 27]. In contrast, results from a recent randomised trial found that practice using simple basic skills compared with a nephrectomy module gave better results when performing a VATS lobectomy in a simulated setting [9]. This is surprising, since the nephrectomy module is more similar to a VATS lobectomy in terms of task resemblance.

A randomised trial has shown that, compared to no training at all, practicing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy on a virtual reality simulator resulted in improved performance when practicing a laparoscopic nephrectomy in a porcine model [8]. This shows that some degree of skills-transfer is seen between different laparoscopic procedures. Furthermore, previous trials have focused on examining the effect in a single-test setting, not considering the effect on the learning process for reaching proficiency for a skill. Developing procedural modules for virtual reality training is very challenging and time-consuming, and it is therefore essential to determine whether it is necessary to develop training modules for many procedures.

Cognitive load

Increased cognitive load can negatively influence the learning of a new skill and simulator training can be used the to reduce the cognitive load and help facilitate the learning process [28]. Through practicing a procedure on a simulator, the surgical novice can become familiar with the procedure, learn critical steps and how to avoid possible adverse events. For novices, the cognitive load associated with learning a new procedure gradually decreases with continuous simulator practice [14]. Whether this reduction in cognitive load is generalizable and still present when learning a new procedure is unknown and has not been previously examined.

Trial strengths and limitations

The strength of the present trial is the use of a trial design that mirrors an actual curriculum, because it incorporates both proficiency-based training and distributed practice [29]. Therefore, the findings can probably be applied to actual training in simulation centres. The use of basic skills training to ensure the same proficiency level before randomisation helps standardise the intervention with the procedural modules because the participants have a similar starting point in terms of basic laparoscopic skills. Additionally, use of the same training equipment minimises the risk of confounding from variations in training conditions.

The trial is designed in order to minimise the risks of systematic errors and the risks of random errors [30–32]. Systematic errors have been sought to be reduced by central randomisation stratified for prognostic factors [30–32]. Blinding is used whenever possible and data is analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. We are aware that some outcomes are at risk of being assessed with some bias, as they are not possible to blind [30–32].

A limitation is the trial participants are medical students instead of novice surgical residents; however, previous studies have shown that medical students’ performance on the simulator is similar to that of novice surgical residents [10, 11]. There are only approximately 50 first-year residents in surgery and gynaecology in the region every year, and they vary greatly in laparoscopic experience; thus, the trial would not have been feasible with first-year residents. Ideally, the trial should include transfer to the clinical settings using clinical outcomes, but this is not feasible due to the large sample size that is required and the difficulty with finding relevant clinical outcomes [33].

Trial status

Currently, participants are being included and randomisation is still ongoing. Data collection is expected to end in September of 2014.

References

Strandbygaard J, Bjerrum F, Maagaard M, Rifbjerg Larsen C, Ottesen B, Sorensen JL: A structured four-step curriculum in basic laparoscopy: development and validation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014, 93: 359-366. 10.1111/aogs.12330.

Reznick RK, Macrae H: Teaching surgical skills–changes in the wind. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 2664-2669. 10.1056/NEJMra054785.

Grantcharov TP, Reznick RK: Teaching procedural skills. BMJ. 2008, 336: 1129-1131. 10.1136/bmj.39517.686956.47.

Våpenstad C, Buzink SN: Procedural virtual reality simulation in minimally invasive surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013, 27: 364-377. 10.1007/s00464-012-2503-1.

Schreuder HWR, van Hove PD, Janse JA, Verheijen RRM, Stassen LPS, Dankelman J: An “intermediate curriculum” for advanced laparoscopic skills training with virtual reality simulation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011, 18: 597-606. 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.05.017.

Kolozsvari NO, Kaneva P, Brace C, Chartrand G, Vaillancourt M, Cao J, Banaszek D, Demyttenaere S, Vassiliou MC, Fried GM, Feldman LS: Mastery versus the standard proficiency target for basic laparoscopic skill training: effect on skill transfer and retention. Surg Endosc. 2011, 25: 2063-2070. 10.1007/s00464-011-1743-9.

Sabbagh R, Chatterjee S, Chawla A, Kapoor A, Matsumoto ED: Task-specific bench model training versus basic laparoscopic skills training for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled study. Can Urol Assoc J. 2009, 3: 22-30.

Lucas SM, Zeltser IS, Bensalah K, Tuncel A, Jenkins A, Pearle MS, Cadeddu JA: Training on a virtual reality laparoscopic simulator improves performance of an unfamiliar live laparoscopic procedure. J Urol. 2008, 180: 2588-2591. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.041. discussion 2591

Jensen K, Ringsted C, Hansen HJ, Petersen RH, Konge L: Simulation-based training for thoracoscopic lobectomy: a randomized controlled trial: virtual-reality versus black-box simulation. Surg Endosc. 2014, 28: 1821-1829. 10.1007/s00464-013-3392-7.

Strandbygaard J, Bjerrum F, Maagaard M, Winkel P, Larsen CR, Ringsted C, Gluud C, Grantcharov T, Ottesen B, Sorensen JL: Instructor feedback versus no instructor feedback on performance in a laparoscopic virtual reality simulator: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2013, 257: 839-844. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827eee6e.

Larsen CR, Soerensen JL, Grantcharov TP, Dalsgaard T, Schouenborg L, Ottosen C, Schroeder TV, Ottesen BS: Effect of virtual reality training on laparoscopic surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009, 338: b1802-10.1136/bmj.b1802.

Zijlstra F: PhD thesis. Efficiency in Work Behaviour: A Design Approach for Modern Tools. 1993, Netherlands: Delft University of Technology

van der Schatte Olivier RH, Van't Hullenaar CDP, Ruurda JP, Broeders IAMJ: Ergonomics, user comfort, and performance in standard and robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2009, 23: 1365-1371. 10.1007/s00464-008-0184-6.

Bharathan R, Vali S, Setchell T, Miskry T, Darzi A, Aggarwal R: Psychomotor skills and cognitive load training on a virtual reality laparoscopic simulator for tubal surgery is effective. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013, 169: 347-352. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.03.017.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group: CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010, 8: 18-10.1186/1741-7015-8-18.

Atkinson A, Riani MA: Robust Diagnostic Regression Analysis. 2000, New York, NY: Springer

Efron B, Tibshirani R: An Introduction to the Bootstrap. 1993, New York: Chapman & Hall

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Ser. 1995, 57: 289-300.

Hiemstra E, Kolkman W, Jansen FW: Skills training in minimally invasive surgery in Dutch obstetrics and gynecology residency curriculum. Gynecol Surg. 2008, 5: 321-325. 10.1007/s10397-008-0402-1.

Schreuder H, van den Berg C, Hazebroek E, Verheijen R, Schijven M: Laparoscopic skills training using inexpensive box trainers: which exercises to choose when constructing a validated training course. BJOG. 2011, 119: 263-265.

Magill R, Anderson D: Motor Learning and Control: Concepts and Applications. 2013, New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education

Ericsson KA: The Influence of Experience and Deliberate Practice on the Development of Superior Expert Performance. The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance. Edited by: Ericsson KA, Charness N, Feltovich PJ, Hoffman RR. 2006, New York: Cambridge University Press, 683-704.

Ericsson KA: Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004, 79: S70-81.

Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, Hatala R, Zendejas B, Cook DA: Reconsidering fidelity in simulation-based training. Acad Med. 2014, 89: 387-392. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000130.

Sabbagh R, Chatterjee S, Chawla A, Hoogenes J, Kapoor A, Matsumoto ED: Transfer of laparoscopic radical prostatectomy skills from bench model to animal model: a prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled study. J Urol. 2012, 187: 1861-1866. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.12.050.

O'keeffe SL, Harrison AJ, Smyth PJ: Transfer or specificity? An applied investigation into the relationship between fundamental overarm throwing and related sport skills. Phys Educ Sport Pedagog. 2007, 12: 89-102. 10.1080/17408980701281995.

Moradi J, Movahedi A, Salehi H: Specificity of learning a sport skill to the visual condition of acquisition. J Mot Behav. 2014, 46: 17-23. 10.1080/00222895.2013.838935.

Young JQ, Van Merrienboer J, Durning S, Ten Cate O: Cognitive Load Theory: Implications for medical education: AMEE Guide No. 86. Med Teach. 2014, 36: 371-384. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.889290.

Spruit EN, Band GPH, Hamming JF, Ridderinkhof KR: Optimal training design for procedural motor skills: a review and application to laparoscopic surgery. Psychol Res. 2013, [Epub ahead of print]

Savović J, Jones HE, Altman DG, Harris RJ, Jüni P, Pildal J, Als-Nielsen B, Balk EM, Gluud C, Gluud LL, Ioannidis JPA, Schulz KF, Beynon R, Welton NJ, Wood L, Moher D, Deeks JJ, Sterne JAC: Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2012, 157: 429-438. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00537.

Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Jüni P, Altman DG, Gluud C, Martin RM, Wood AJG, Sterne JAC: Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2008, 336: 601-605. 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD.

Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C: Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med. 2001, 135: 982-989. 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00010.

Cook DA, West CP: Perspective: Reconsidering the focus on “outcomes research” in medical education: a cautionary note. Acad Med. 2013, 88: 162-167. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c3d78.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/14/215/prepub

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Cathrine Vedel for performing external data monitoring. The trial is supported by a grant from the non-profit organisation TrygFonden. The authors are solely responsible for the content of the manuscript, which does not necessarily represent the official view of TrygFonden.

Funding

TrygFonden (Grant id 102169).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FB conceived the idea for the study, which was developed in collaboration with JS, JLS, LK and BO. FB and JL drafted the protocol and planned the trial. FB is the principal investigator and responsible for data collection. FB and SR drafted the plan for statistical analysis. LK assisted with logistical support. All authors revised the manuscript, read and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bjerrum, F., Sorensen, J.L., Konge, L. et al. Procedural specificity in laparoscopic simulator training: protocol for a randomised educational superiority trial. BMC Med Educ 14, 215 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-215

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-215