Abstract

Background

Although carbohydrate reduction of varying degrees is a popular and controversial dietary trend, potential long-term effects for health, and cancer in specific, are largely unknown.

Methods

We studied a previously established low-carbohydrate, high-protein (LCHP) score in relation to the incidence of cancer and specific cancer types in a population-based cohort in northern Sweden. Participants were 62,582 men and women with up to 17.8 years of follow-up (median 9.7), including 3,059 prospective cancer cases. Cox regression analyses were performed for a LCHP score based on the sum of energy-adjusted deciles of carbohydrate (descending) and protein (ascending) intake labeled 1 to 10, with higher scores representing a diet lower in carbohydrates and higher in protein. Important potential confounders were accounted for, and the role of metabolic risk profile, macronutrient quality including saturated fat intake, and adequacy of energy intake reporting was explored.

Results

For the lowest to highest LCHP scores, 2 to 20, carbohydrate intakes ranged from median 60.9 to 38.9% of total energy intake. Both protein (primarily animal sources) and particularly fat (both saturated and unsaturated) intakes increased with increasing LCHP scores. LCHP score was not related to cancer risk, except for a non-dose-dependent, positive association for respiratory tract cancer that was statistically significant in men. The multivariate hazard ratio for medium (9–13) versus low (2–8) LCHP scores was 1.84 (95% confidence interval: 1.05-3.23; p-trend = 0.38). Other analyses were largely consistent with the main results, although LCHP score was associated with colorectal cancer risk inversely in women with high saturated fat intakes, and positively in men with higher LCHP scores based on vegetable protein.

Conclusion

These largely null results provide important information concerning the long-term safety of moderate carbohydrate reduction and consequent increases in protein and, in this cohort, especially fat intakes. In order to determine the effects of stricter carbohydrate restriction, further studies encompassing a wider range of macronutrient intakes are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, low-carbohydrate diets have emerged as a controversial and popular means of achieving weight loss and controlling diabetes. In Sweden, extensive positive media support for dietary carbohydrate restriction has occurred over the past 5–7 years [1]. During the same time period, in northern Sweden, a complete reversal of previous reductions in fat intake and cholesterol levels has been reported in the general population [2, 3]. Discerning the potential long-term health effects of carbohydrate restriction, not only of stringent low-carbohydrate diets but also of more modest carbohydrate reduction, is thus an important challenge in nutrition research today.

For weight loss, low-carbohydrate diets, both extremely or more modestly reduced in carbohydrate (e.g. E% carbohydrates/protein/fat = 9/28/63 [4], and 44/18/38 [5], respectively) have been found to be at least as effective as traditional low-calorie/low-fat diets over a period of up to two years [5–7]. The results of randomized trials have also tended to support improved metabolic parameters and blood lipids [8–11], but elevated markers of stress and inflammation [11–13] in subjects following a low-carbohydrate diet. These alterations might influence the risk of major chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer [11, 14]. However, from a long-term perspective, the effects of carbohydrate reduction of varying degrees, and consequent increased consumption of various types of protein and/or fat, for health outcomes, and cancer in specific, are largely unknown.

The results of previous epidemiological studies in general populations have suggested positive or null associations between low-carbohydrate diet scores, particularly scores representing diets higher in foods of animal origin, and all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality [15–19]. Prospective studies of cardiovascular disease incidence have reported either an increased risk [20], or reduced risk for plant-based [21], carbohydrate-restricted diets. The only previous prospective study to address overall cancer incidence found null associations for both animal- and plant-based low-carbohydrate diets [22]. An increased risk of incident breast cancer has been observed for a dietary pattern characterized by a low intake of bread and fruit juice and a high intake of processed meat, fish, butter, other animal fats, and margarine [23]. In contrast, a plant-based, low-carbohydrate diet has been related to a reduced risk of estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer [24].

Given the high rates of overweight and obesity worldwide, and the widespread popularity of low-carbohydrate diets, evaluation of the long-term safety of carbohydrate restriction of varying degrees is crucial. The aim of the present study was to investigate macronutrient distribution, in particular a previously established low-carbohydrate, high-protein (LCHP) score [16–20], in relation to the risk of incident cancer and specific types of cancer in a large, population-based cohort in northern Sweden.

Methods

Study design and cohort

The Västerbotten Intervention Programme (VIP) is an ongoing, population-based, prospective cohort study and health intervention, including residents of the northern Swedish county of Västerbotten turning 40, 50 and 60 years of age. Until 1996, 30 year olds were also included. The VIP protocol, described in detail elsewhere [25, 26], includes a health examination, with measurement of a number of potential health risk factors, such as an oral glucose tolerance test, as well as a participant-administered diet and lifestyle questionnaire. For the period assessed in this study, 1990–2007, the average recruitment rate was 59% . The VIP food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) has been validated by 24-hour-recall interviews [27], and by biomarkers in blood samples collected from VIP participants [28, 29]. Cancer incidences comparable to those of the general population in Västerbotten indicate a truly population-based cohort [30], and no selection bias of importance has been demonstrated [31].

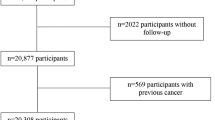

As of December 31, 2007, when cases of incident cancer were identified for the present study, a total of 82,879 participation occasions (66,001 individuals) had been registered within the VIP cohort. From these we excluded 1,328 participation occasions with missing data for more than 10% of the items in the FFQ and/or portion size, 32 participation occasions with missing height or weight data, 9 participation occasions with a body mass index (BMI) <10, and 6,112 participation occasions with food intake level (FIL) in the lowest 5th percentile or the highest 2.5th percentile (specific to sex and FFQ version and based on the first sampling occasion for subjects with repeated measures), and 12,816 participants with more than one sampling occasion (most recent sampling occasion excluded). The final study population thus included 62,582 participants (31,397 men, 31,185 women).

Identification of cancer cases

A total of 3,059 incident, prospective cancer cases without previous cancer diagnosis, except non-melanoma skin cancer, were identified through linkage with the regional branch of the national cancer registry, with site-specific cancers defined according to the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-7 [32], as follows: prostate (177), breast (170), colorectum (153, 154.0), respiratory tract (161, 162), urinary tract (181), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (200, 202), endometrium (172), malignant melanoma (190), leukemia (204–207), pancreas (157), ovary 175.0), stomach (151), multiple myeloma (203) and renal cell (180.0, 180.9).

Low-carbohydrate, high-protein score

Dietary intake of macronutrients was calculated from food frequency questionnaires with 9 fixed response alternatives ranging from never to ≥4 times per day and including 84 (years 1990–1996) or 65 (years 1997–2007) food items, as well as photo-based portion-size estimations for meat/fish, potatoes/pasta/rice, and vegetables [26]. The 65-item FFQ was an abbreviated version of the 84-item FFQ, in which some food items had been merged and some deleted as described elsewhere [33] (p 26). All intake variables except ethanol were energy adjusted according to the residual method [34].

Descending deciles, or tenths, of energy-adjusted carbohydrate and ascending deciles of energy-adjusted protein were labeled 1 to 10 and summed to create an LCHP score (2–20 points), a model employed in several previous studies [16–20]. The LCHP score is independent of total energy intake, due to the isocaloric nature of carbohydrate and protein, and it allows separate consideration of the amount and quality of fat consumed. LCHP scores were also categorized into low (2–8 points), medium (9–13 points) and high (14–20 points), in order to approximate equally sized groups.

Statistical analyses

Differences in baseline characteristics of the study subjects according to LCHP score category were determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were determined between LCHP score and intakes of fat and saturated fat and sex-specific analyses were done. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for overall cancer incidence and for all types of cancer with at least 50 cases were calculated by Cox proportional hazard regression models. HR are presented for medium and high versus low LCHP scores or per 1-point increase in LCHP score. p-trend were calculated per 1-point increase in LCHP score. Age and BMI deviated from the proportional hazard assumption according to Schoenfeld’s test. Age was thus examined in 10-year intervals, included as strata in the crude and multivariate models, and BMI was dichotomized according to obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).

Of an extensive list of potential confounding variables, only saturated fat intake altered any HR for LCHP by more than 10% when included in a bivariate model. The final multivariate model included age (10-year intervals, strata), obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, yes/no), sedentary lifestyle (no physical activity in exercise clothes, yes/no), education (lack of postsecondary, yes/no), current smoking (yes/no), and intake of alcohol (g/day), saturated fat (energy-adjusted residual), and total energy intake (Kcal/day), all selected for their theoretical importance. Missing data, present only for some categorical covariates, i.e. education, N = 377 (0.6%), sedentary lifestyle, N = 1,751 (2.8%), smoking, N = 706 (1.1%), were treated as dummy variables.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for metabolic risk profile, defined as at least one of, versus none of, obesity, diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or post-load plasma glucose ≥12.2 mmol/l, and impaired glucose tolerance was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥6.1 mmol/l and/or post-load plasma glucose ≥8.9 mmol/l. Subgroups based on saturated fat intake (energy adjusted and stratified at the median) and energy reporting (adequate versus inadequate, according to the Goldberg cut-off, modified as described in our previous report [19]) were also examined. The subgroup analyses were limited to overall cancer incidence and cancer of the prostate, breast and colorectum, which were the most common sites. Heterogeneity was tested by Chi-square analysis. A sub-analysis was also performed for the time period prior to the shift in macronutrient intake in the VIP population [2] (follow-up to December 31, 2002). All tests were two-sided, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Northern Sweden (dossier number 07-165 M). All study subjects provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Follow-up times ranged from 1 day to 17.9 years, median 9.7 years. Macronutrient intakes for the lowest to highest LCHP scores (2–20 points) ranged from median 60.9 to 38.9% of total energy intake for carbohydrate, 11.3 to 18.9% for protein, and 26.7 to 41.5% for fat. Relationships between baseline characteristics and LCHP score are presented in Table 1. High LCHP scores were associated with younger age (not apparent in medians due to sampling at 10-year age intervals) and higher BMI, prevalence of current smokers, sedentary lifestyle (women only) and alcohol intake. Lack of postsecondary education was more common in men with low LCHP scores and in women with high scores. LCHP scores were positively related to intake of animal protein, but negatively related to plant protein. For carbohydrate and fat, associations were consistent in sucrose and whole grain and saturated and unsaturated fat, respectively. Spearman correlation coefficients for LCHP score and energy-adjusted fat, saturated fat and unsaturated fat intakes were 0.51, 0.45, and 0.46, respectively.

There were no statistically significant associations between LCHP score and any cancer, with the exception of an increased risk of respiratory tract cancer for medium LCHP scores in men (multivariate HR for medium versus low LCHP scores 1.84; 95% CI 1.05-3.23; p-trend = 0.38) (Table 2). HR for high versus low LCHP scores for respiratory tract cancer were above one in both men and women, but not statistically significant.

Subgroup analyses based on metabolic risk profile, saturated fat intake, and energy reporting [19], had no material effects on results (Table 3). The only statistically significant finding was an inverse association between LCHP score and colorectal cancer risk in women with high saturated fat intakes (multivariate HR for a 1-point increase in LCHP score 0.92; 95% CI 0.87-0.98; p = 0.013; p-heterogeneity = 0.003). Constructing LCHP scores in which whole grain or sucrose replaced total carbohydrates, and in which vegetable or animal protein replaced total protein intake (data not shown), also did not differ from the main findings, except a statistically significant increased risk of colorectal cancer in men with higher LCHP scores based on vegetable protein (multivariate HR for a 1-point increase in LCHP score 1.07; 95% CI 1.01-1.14; p = 0.029; p-heterogeneity = 0.016).

In analyses restricted to the time period up to and including December 31, 2002, there was a tendency towards a positive association between high LCHP scores and overall cancer risk in both men (multivariate HR for high versus low LCHP scores 1.25; 95% CI 0.86-1.80; p-trend = 0.093) and women, (multivariate HR for high versus low LCHP scores 1.39; 95% CI 0.98-1.96; p-trend = 0.020) (Table 4). For prostate, breast and colorectal cancers no significant associations were found.

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study with a follow-up period of up to 17.9 years, a diet moderately low in carbohydrates and moderately high in protein was largely unrelated to overall and site-specific cancer incidence, regardless of the quantity and quality of fat intake.

The one previous prospective study to report results for overall cancer incidence, from the Iowa Women’s Health Study, reported inverse risk relationships for isocaloric substitution of either animal or vegetable protein for carbohydrates [22]. However, the results were attenuated to null in multivariate analyses. Associations reported for overall cancer mortality have also been null, non-statistically significant, or unstable [15, 17, 19, 22]. Taken together, the evidence to date does not support a role for moderate carbohydrate reduction in determining the overall risk of cancer.

Increasing LCHP scores were associated with an elevated risk of respiratory tract cancer in both men and women in the present study, but the relationship was not dose dependent and was only statistically significant for medium LCHP scores in men. Although these observations may be due to chance or reflect residual confounding due to smoking, they are consistent with a previous finding for lung cancer mortality [15]. Further study is therefore warranted.

There are several mechanisms by which a carbohydrate-reduced diet could influence carcinogenesis, through specific food items or components, such as red and processed meat for example [35], or through effects on energy metabolism and body composition [36–39]. In analyses considering macronutrient quality and metabolic profile at baseline, two statistically significant results were observed, an inverse association between LCHP score and colorectal cancer risk in women with high saturated fat intakes, and an increased risk of colorectal cancer in men with higher LCHP scores based on vegetable protein. These findings do not support the hypothesis that high animal protein intake increases the risk for these cancer types. Previously, we have reported a null association between LCHP score and colorectal cancer mortality [19], and a positive association has been noted for an animal-based, low-carbohydrate score and colorectal cancer mortality [15]. The latter finding is more consistent with the current understanding of the role of diet in colorectal cancer. For example, there is convincing evidence that a high consumption of protein sources such as red and processed meat is associated with increased colorectal cancer risk [35]. Furthermore, in a controlled trial, a LCHP weight-loss diet has been observed to reduce fecal cancer-protective metabolites and increase hazardous metabolites, which could increase the risk of colon cancer [40].

The limited variability in macronutrient distribution in the study population may have prevented the detection of associations with cancer risk. In particular, the role of stricter carbohydrate restriction could not be assessed. This is an issue common to both the present and previous studies [15, 17, 19, 22]. Interindividual differences, such as gene-nutrient interactions and epigenetics, both emerging research fields [36], may also complicate the relationship between macronutrient distribution and cancer risk. Furthermore, carbohydrate restriction might have different roles in different stages of tumorigenesis, making it difficult to detect overall effects on incidence. For example, putative mechanisms for a role for carbohydrate in the progression from premalignant lesion to cancer diagnosis include metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells resulting in increased glycolysis and glucose requirements, the so-called Warburg effect, as well as the stimulatory effect of insulin-like growth factor on proliferating cells [37, 41].

In northern Sweden, a rapid decline in fat intake and hypercholesterolemia occurred between the years 1986–1992 [42], attributed in part to the cardiovascular disease prevention activities of the VIP [42]. Today fat intake has reached the peak levels of the 1980’s, and carbohydrate intake is decreasing [2]. LCHP scores have increased in VIP participants with repeated samples 10 years apart [19]. Furthermore, blood cholesterol concentrations in the northern Swedish population are increasing, despite increasing use of cholesterol-lowering drugs [3]. These temporal changes may have attenuated our results, as indicated by the positive association between a high LCHP score and overall cancer incidence in the sub-analysis restricted to the time period 1990–2002, when LCHP score was relatively stable in the VIP population. In the present study, roughly equal amounts of saturated and unsaturated fat replaced most of the carbohydrate reduction in subjects with high LCHP scores, and the excess protein consumed by subjects with high LCHP scores was primarily of animal origin. In Sweden, extensive positive media focus for carbohydrate-restricted diets in recent years has largely promoted fat, often animal fat, rather than protein, as the substitute for carbohydrates [1, 43]. The general enthusiasm for carbohydrate reduction, and the apparent preference for animal-based replacement foods in Sweden, thus underscores the importance of evaluating potential long-term implications for health.

The main strengths of this study were the large, population-based cohort, the extensive data available, such as an oral glucose tolerance test and BMI measured by health professionals, and the long, essentially complete, follow-up. In addition, the prospective study design reduced the risk of recall bias and reverse causation. We used an established LCHP score, which has been employed in previous studies [16–18]. The LCHP score does not include fat intake. However, unlike macronutrient scores that incorporate fat, the LCHP score is independent of total energy intake. It is also simple, both to calculate and interpret, and it allowed separate consideration of the amount and quality of fat consumed. Food frequency questionnaires like the one employed is this study have inherent weaknesses, such as being a relatively inexact tool for the measurement of total nutrient and energy intake, but they are generally adequate for ranking and are an accepted and practical tool for large-scale epidemiological studies. Although several potential confounders were accounted for, residual confounding due to factors not measured (such as food items not included in the FFQ) or not adequately estimated (such as history of tobacco use) was likely present. Since we consider this study to be exploratory, the results were not corrected for multiple testing. The risk of chance findings should therefore be acknowledged. Numbers of cases were also low for some cancer types and in some subgroup analyses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this population-based, cohort study do not support an important role for a diet moderately low in carbohydrates and moderately high in protein, regardless of the quantity and quality of fat consumed, in determining the overall, long-term risk of cancer, although a possible increased risk of respiratory cancer was observed and a tendency of an increased general cancer risk over shorter time. Given the current widespread popularity of carbohydrate-restricted diets, and the limited data concerning potential long-term health effects of carbohydrate reduction and consequent increases in protein and/or fat intakes, these findings are important. In order to evaluate the role of more stringent carbohydrate restriction, investigations encompassing a wider range of macronutrient intakes, such as multicenter studies, will be needed.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FIL:

-

Food intake level

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- LCHP:

-

Low-carbohydrate high-protein

- VIP:

-

The västerbotten intervention programme.

References

Mann J, Nye ER: Fad diets in sweden, of all places. Lancet. 2009, 374: 767-769. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61575-0.

Johansson I, Nilsson L, Stegmayr B, Boman K, Hallmans G, Winkvist A: Associations among 25-year trends in diet, cholesterol and BMI from 140,000 observations in men and women in northern sweden. Nutr J. 2012, 11: 40-10.1186/1475-2891-11-40.

Ng N, Johnson O, Lindahl B, Norberg M: A reversal of decreasing trends in population cholesterol levels in vasterbotten county, sweden. Glob Health Action. 2012, 5:

Volek J, Sharman M, Gomez A, Judelson D, Rubin M, Watson G, Sokmen B, Silvestre R, French D, Kraemer W: Comparison of energy-restricted very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on weight loss and body composition in overweight men and women. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2004, 1: 13-10.1186/1743-7075-1-13.

Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Smith SR, Ryan DH, Anton SD, McManus K, Champagne CM, Bishop LM, Laranjo N: Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360: 859-873. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748.

Samaha FF, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Chicano KL, Daily DA, McGrory J, Williams T, Williams M, Gracely EJ, Stern L: A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348: 2074-2081. 10.1056/NEJMoa022637.

Katan MB: Weight-loss diets for the prevention and treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360: 923-925. 10.1056/NEJMe0810291.

Layman DK, Clifton P, Gannon MC, Krauss RM, Nuttall FQ: Protein in optimal health: heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 87: 1571S-1575S.

Hession M, Rolland C, Kulkarni U, Wise A, Broom J: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities. Obes Rev. 2009, 10: 36-50. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00518.x.

Kirk JK, Graves DE, Craven TE, Lipkin EW, Austin M, Margolis KL: Restricted-carbohydrate diets in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108: 91-100. 10.1016/j.jada.2007.10.003.

Ebbeling CB, Swain JF, Feldman HA, Wong WW, Hachey DL, Garcia-Lago E, Ludwig DS: Effects of dietary composition on energy expenditure during weight-loss maintenance. JAMA. 2012, 307: 2627-2634. 10.1001/jama.2012.6607.

Stimson RH, Johnstone AM, Homer NZ, Wake DJ, Morton NM, Andrew R, Lobley GE, Walker BR: Dietary macronutrient content alters cortisol metabolism independently of body weight changes in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92: 4480-4484. 10.1210/jc.2007-0692.

Rankin JW, Turpyn AD: Low carbohydrate, high fat diet increases C-reactive protein during weight loss. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007, 26: 163-169.

Tete S, Nicoletti M, Saggini A, Maccauro G, Rosati M, Conti F, Cianchetti E, Tripodi D, Toniato E, Fulcheri M: Nutrition and cancer prevention. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012, 25: 573-581.

Fung TT, van Dam RM, Hankinson SE, Stampfer M, Willett WC, Hu FB: Low-carbohydrate diets and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: two cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2010, 153: 289-298. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-5-201009070-00003.

Trichopoulou A, Psaltopoulou T, Orfanos P, Hsieh CC, Trichopoulos D: Low-carbohydrate-high-protein diet and long-term survival in a general population cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007, 61: 575-581.

Lagiou P, Sandin S, Weiderpass E, Lagiou A, Mucci L, Trichopoulos D, Adami HO: Low carbohydrate-high protein diet and mortality in a cohort of swedish women. J Intern Med. 2007, 261: 366-374. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01774.x.

Sjogren P, Becker W, Warensjo E, Olsson E, Byberg L, Gustafsson IB, Karlstrom B, Cederholm T: Mediterranean and carbohydrate-restricted diets and mortality among elderly men: a cohort study in sweden. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 92: 967-974. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29345.

Nilsson LM, Winkvist A, Eliasson M, Jansson JH, Hallmans G, Johansson I, Lindahl B, Lenner P, Van Guelpen B: Low-carbohydrate, high-protein score and mortality in a northern swedish population-based cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012, 66 (6): 694-700. 10.1038/ejcn.2012.9. Epub 2012/02/16

Lagiou P, Sandin S, Lof M, Trichopoulos D, Adami HO, Weiderpass E: Low carbohydrate-high protein diet and incidence of cardiovascular diseases in swedish women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012, 344: e4026-10.1136/bmj.e4026.

Halton TL, Willett WC, Liu S, Manson JE, Albert CM, Rexrode K, Hu FB: Low-carbohydrate-diet score and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 1991-2002. 10.1056/NEJMoa055317.

Kelemen LE, Kushi LH, Jacobs DR, Cerhan JR: Associations of dietary protein with disease and mortality in a prospective study of postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2005, 161: 239-249. 10.1093/aje/kwi038.

Schulz M, Hoffmann K, Weikert C, Nothlings U, Schulze MB, Boeing H: Identification of a dietary pattern characterized by high-fat food choices associated with increased risk of breast cancer: the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)-potsdam study. Br J Nutr. 2008, 100: 942-946. 10.1017/S0007114508966149.

Fung TT, Hu FB, Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Holmes MD: Low-Carbohydrate Diets, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension-Style Diets, and the Risk of Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2011, 174 (6): 652-660. 10.1093/aje/kwr148. Epub 2011/08/13

Weinehall L, Hellsten G, Boman K, Hallmans G: Prevention of cardiovascular disease in sweden: the norsjo community intervention programme–motives, methods and intervention components. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2001, 56: 13-20.

Winkvist A, Hornell A, Hallmans G, Lindahl B, Weinehall L, Johansson I: More distinct food intake patterns among women than men in northern sweden: a population-based survey. Nutr J. 2009, 8: 12-10.1186/1475-2891-8-12.

Johansson I, Hallmans G, Wikman A, Biessy C, Riboli E, Kaaks R: Validation and calibration of food-frequency questionnaire measurements in the northern sweden health and disease cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5: 487-496.

Wennberg M, Vessby B, Johansson I: Evaluation of relative intake of fatty acids according to the northern sweden FFQ with fatty acid levels in erythrocyte membranes as biomarkers. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12: 1477-1484. 10.1017/S1368980008004503.

Johansson I, Van Guelpen B, Hultdin J, Johansson M, Hallmans G, Stattin P: Validity of food frequency questionnaire estimated intakes of folate and other B vitamins in a region without folic acid fortification. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010, 64: 905-913. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.80.

Pukkala E, Andersen A, Berglund G, Gislefoss R, Gudnason V, Hallmans G, Jellum E, Jousilahti P, Knekt P, Koskela P: Nordic biological specimen banks as basis for studies of cancer causes and control–more than 2 million sample donors, 25 million person years and 100,000 prospective cancers. Acta Oncol. 2007, 46: 286-307. 10.1080/02841860701203545.

Weinehall L, Hallgren CG, Westman G, Janlert U, Wall S: Reduction of selection bias in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease through involvement of primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1998, 16: 171-176. 10.1080/028134398750003133.

Percy C: International classification of diseases for oncology: ICD-O. 1990, Geneva: World Health Organization

Nilsson LM: Sami lifestyle and health [elektronisk resurs] : epidemiological studies from northern sweden. 2012, Umeå: Umeå university

Willett W, Stampfer MJ: Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1986, 124: 17-27.

WCRF, AIRC: World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. 2007, Washington DC: AICR, 284-Available at url: http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/4841/1/4841.pdf, accessed January 20132011

Ross SA: Evidence for the relationship between diet and cancer. Exp Oncol. 2010, 32: 137-142.

Klement RJ, Kammerer U: Is there a role for carbohydrate restriction in the treatment and prevention of cancer?. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011, 8: 75-10.1186/1743-7075-8-75.

Cowey S, Hardy RW: The metabolic syndrome: a high-risk state for cancer?. Am J Pathol. 2006, 169: 1505-1522. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051090.

Abete I, Astrup A, Martinez JA, Thorsdottir I, Zulet MA: Obesity and the metabolic syndrome: role of different dietary macronutrient distribution patterns and specific nutritional components on weight loss and maintenance. Nutr Rev. 2010, 68: 214-231. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00280.x.

Russell WR, Gratz SW, Duncan SH, Holtrop G, Ince J, Scobbie L, Duncan G, Johnstone AM, Lobley GE, Wallace RJ: High-protein, reduced-carbohydrate weight-loss diets promote metabolite profiles likely to be detrimental to colonic health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011, 93: 1062-1072. 10.3945/ajcn.110.002188.

Ferreira LM, Hebrant A, Dumont JE: Metabolic reprogramming of the tumor. Oncogene. 2012, 31: 3999-4011. 10.1038/onc.2011.576.

Weinehall L, Westman G, Hellsten G, Boman K, Hallmans G, Pearson TA, Wall S: Shifting the distribution of risk: results of a community intervention in a swedish programme for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999, 53: 243-250. 10.1136/jech.53.4.243.

Marcus C, Hallmans G, Johansson G, Rothenberg E, Rossner S: [High-fat diet intake can be questioned]. Lakartidningen. 2008, 105: 1864-1866.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Cancer Research Foundation in Northern Sweden, Nordic Health and Whole grain Food (HELGA)/Nordforsk, the Swedish Research Council and the Västerbotten County Council. We also acknowledge the Västerbotten Intervention Programme participants and the VIP diet database team.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Cancer Research Foundation in Northern Sweden, Nordic Health and Whole grain Food (HELGA)/Nordforsk, the Swedish Research Council and the Västerbotten County Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

LMN, AW, IJ, GH, and BVG designed and conducted the research. LMN analyzed the data. LMN and BVG interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript, and LMN had primary responsibility for the final content. AW, IJ, BL, GH, and PL contributed important scientific content, and all authors revised manuscript drafts and read and approved the final version.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nilsson, L.M., Winkvist, A., Johansson, I. et al. Low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet score and risk of incident cancer; a prospective cohort study. Nutr J 12, 58 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-58

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-58