Abstract

Background

Internet addiction among US college students remains a concern, but robust estimates of its prevalence are lacking.

Methods

We conducted a pilot survey of 307 college students at two US universities. Participants completed the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) as well as the Patient Health Questionnaire. Both are validated measures of problematic Internet usage and depression, respectively. We assessed the association between problematic Internet usage and moderate to severe depression using a modified Poisson regression approach. In addition, we examined the associations between individual items in the IAT and depression.

Results

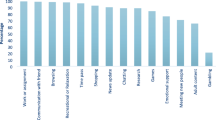

A total of 224 eligible respondents completed the survey (73% response rate). Overall, 4% of students scored in the occasionally problematic or addicted range on the IAT, and 12% had moderate to severe depression. Endorsement of individual problematic usage items ranged from 1% to 70%. In the regression analysis, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with several individual items. Relative risk could not be estimated for three of the twenty items because of small cell sizes. Of the remaining 17 items, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with 13 of them, and three others had P values less than 0.10. There was also a significant association between problematic Internet usage overall and moderate to severe depression (relative risk 24.07, 95% confidence interval 3.95 to 146.69; P = 0.001).

Conclusion

The prevalence of problematic Internet usage among US college students is a cause for concern, and potentially requires intervention and treatment amongst the most vulnerable groups. The prevalence reported in this study is lower than that which has been reported in other studies, however the at-risk population is very high and preventative measures are also recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pathological use of the Internet, whether problematic or truly addictive, remains a growing concern worldwide [1]. Absent formal diagnostic criteria, current approaches model problematic Internet usage on the basis of problematic gambling, extrapolating data from one compulsive, nonpharmacologically addictive behavior to another. Currently, there is no recognized psychiatric diagnosis of Internet addiction, although it is being considered for inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [2].

The prevalence of the problem among US children is not known, but a random digit dial survey of US adults found that as many as one in eight adults are considered addicted [3]. Adolescents and young adults are worthy of special consideration, as they have been shown to be at high risk for behavioral addictions [4]. International estimates of adolescent Internet addiction vary widely. In Europe the prevalence has been reported to be between 1% and 9% [5–9], in the Middle East the prevalence is between 1% and 12% [10–12] and in Asia the prevalence has been reported to be between 2% and 18% [13–20]. However, these data must be interpreted with some caution, as varying scales with questionable validity as well as conflicting reports making accurate estimation difficult. Additionally, the field has been hampered by methodological weaknesses of existing research, with the most salient among them being sampling bias. Many early studies in adults relied on voluntary Internet surveys without measurable denominators, convenience samples of Internet users or chat room sampling [21, 22].

College students are a group that may be particularly vulnerable to addiction, as they have largely unfettered, unsupervised access to the Internet and independent control of their time. Estimates of problematic usage in college students vary from 1% to 26% in the US [23–28] and between 6% and 19% internationally [29–31]. Studies in US college students have been limited in several ways, including reliance on a single class for sampling [28] and the use of unvalidated measures or cutoffs [23, 26, 27, 32]. Nevertheless, pediatricians and parents continue to report overuse of the Internet in their patients and children, respectively. Given that the Internet is woven into the fabric of the lives of this generation of children, concerns about the potential for addiction seem warranted and require a systematic estimation of the scope of the problem in a defined population of interest. As part of an ongoing study of college student Internet usage, we collected data on Internet addiction from a representative sample of college students at two large, geographically distinct US universities.

Methods

The study period was between 1 September 2009 and 15 August 2010, and the protocol was approved by both the University of Wisconsin and the University of Washington Institutional Review Boards.

Setting and subjects

To gather a target population of Internet users, this study was conducted using the Facebook social networking site (SNS) [33] to identify participants. Facebook was selected because it is the most popular SNS [34–38]. Over 90% of college students use SNSs, and most report daily use. We investigated publicly available Facebook profiles of undergraduate students within two large state university Facebook networks. To be included in the study, profile owners were required to self-report their ages as 18 to 20 years old and provide evidence of profile activity during the past 30 days. We analyzed only profiles for which we could confirm the profile owner's identity by calling a telephone number listed either on the student's Facebook profile or in the university directory.

Data collection and recruitment

We used the Facebook search engine to identify profiles within our two selected university networks among the freshman, sophomore and junior undergraduate classes. This search yielded 3,038 profiles, all of which were assessed for eligibility. The majority of profiles were ineligible because the profile owners were incorrectly listed and were not undergraduates (n = 448), age under 18 years or over 20 years (n = 313), no age listed (n = 49), no contact information (telephone number or email address) listed on either the Facebook profile or in the university telephone directory (n = 303) or because of privacy settings (n = 1,630). A total of 307 Facebook profiles met all inclusion criteria, and the profile owners were recruited into this study.

For profiles that met inclusion criteria, profile owners were called on the telephone. After verifying the profile owner's identity, the study was explained to the profile owner and permission was requested to send an email that contained further information about the study. If the participant consented to receive the email, an email was sent to the profile owner's university email account that provided detailed information about the study as well as a link to the online survey. The survey was administered online using a Catalyst WebQ online survey engine. Survey respondents were provided a $15 iTunes gift card as compensation.

Primary outcome measures

Our primary outcome variable was the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), which has been validated among adults and is used globally [39]. The IAT is composed of 20 questions, with each response measured on a six-point Likert scale (Not at all, Rarely, Occasionally, Often, Always and Does not apply) [40]. Scores of 20 to 49 represent "average" users, scores of 50 to 79 represent "occasional problems" and scores over 80 are classified as "addicted" [40].

Because cultural norms for college students are different from other adults, rendering statements such as "You become defensive when someone asks you what you do online" of questionable validity, we conducted our analyses using both the overall score as well as the IAT's individual items as outcome measures. Although the IAT's individual items have not been independently validated, several have considerable face validity (namely, "You find that you stay online longer than you intended" and "You try to cut down on the amount of time you spend online").

Covariates

We collected demographic data, including age, race and/or ethnicity and gender, from participating students. In addition, as prior studies have reported associations between depressive symptoms and problematic Internet usage, we had participants complete the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), a validated measure of depression in young adults [29, 41]. The PHQ-9 categorizes respondents as having "no depression," "minimal symptoms," "moderate depression" or "severe depression."

Statistical analysis

We scored the IAT according to the proposed algorithm and then dichotomized it as "average user" [42] versus "occasional problems and addict," with the latter defined here as "problematic user." For our analysis of the individual items on the IAT, we dichotomized each one as "frequently" or more. We dichotomized the PHQ-9 as "moderate to severe depression" and used it as a binary predictor. Because relative risk (RR) is a more interpretable summary of association, and because many of our outcomes are not rare so that odds ratios would not approximate RRs, we used a modified Poisson regression approach to estimate RRs [42, 43]. This approach for estimating RR on the basis of binary data does not require that the outcome follow a Poisson distribution. For our purposes, the Poisson model was a "working model" to facilitate the estimation and did not affect the consistency of the RR estimation. To remove biases in the standard error estimates, we used model robust sandwich standard error estimates for confidence intervals and hypothesis tests. We adjusted for gender, state, age and race and/or ethnicity. None of these covariates were significant, and for simplicity we therefore presented adjusted RRs for the dichotomized PHQ-9 alone.

Results

A total of 224 eligible respondents completed the survey (a 73% response rate). The demographic data of our participants are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 4% of students scored in the occasional problem or addicted range on the IAT, and 12% had moderate to severe depression. Endorsement of individual problematic usage items ranged from 1% to 70% (Table 2). In the regression analysis, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with many individual IAT items. RRs could not be calculated for three of the twenty items because of small cell sizes. Of the remaining 17 items, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with 13 of them and three others had P values less than 0.10. However, some of the confidence intervals were wide because of the small cell sizes (Table 3). Some of the items worth noting are sleep loss, impact on grades and schoolwork and involvement in household chores. There was also a significant association between moderate to severe depression and problematic Internet usage overall (RR = 24.07, 95% confidence interval 3.95 to 146.69; P = 0.001). In other words, students with moderate to severe depression were about 24 times more likely than their peers to exhibit problematic Internet usage.

Discussion

In a representative sample from two large state universities, we found that the prevalence of problematic Internet usage was 4%. To put the prevalence in perspective, if it is confirmed, problematic Internet usage would be as common as asthma in a similar population of children [44]. Beyond problematic usage, it is clear that many college students have concerns about their Internet usage with respect to other relevant domains in their lives. In particular, the fact that 70% reported that they stay online longer than they intend suggests that the ubiquity and ease of access to the Internet are not without a potential downside. Our current understanding of addictions suggests that some people are at greater risk than others based on genetic predisposition [43]. Whether these susceptible individuals actually develop an addiction involves many factors, but repeated exposure to the substrate is clearly necessary, be it to alcohol or to gambling. If we extrapolate that there is, in a similar way, an inherent susceptibility to Internet addiction, then today's college students are clearly at risk, given the considerable exposure that they have to the Internet and the high prevalence of self-expressed concerns about their reliance on it [45].

These findings advance our understanding of Internet addiction by improving upon previous study methodologies in several ways. First, our sampling method targeted college students from two geographically distinct universities and sampled them in their entirety. Given that up to 98% of college students have an SNS profile and that most report daily use, our approach has considerable generalizability [35, 36, 38]. Second, we corroborated an association between depressive symptoms and problematic Internet usage that has been found in international samples [13, 46]. This association lends further validity to the phenomenon of Internet addiction, as depression has been associated with other behavioral addictions, such as gambling [48].

There are several limitations to this study that warrant mention. First, the cross-sectional nature of the analytic plan precludes drawing causal inferences about the association between depressive symptoms and problematic Internet usage. However, others have found similar associations using longitudinal study designs [49]. We suggest that depression and problematic Internet usage are linked in a mutually enhancing cycle wherein depression begets social isolation, which begets problematic Internet usage and thus increases both social isolation and depression. Second, our sample size was modest, making robust estimates difficult, but this does not diminish the statistical significance of our findings. Moreover, on the basis of our findings in an ongoing systematic review of the existing literature that we performed [50], the present study comprises the largest sample of US college students that has used a validated instrument of Internet addiction and that has presented prevalence data on problematic Internet use. Third, many of our potential subjects were excluded because of privacy settings. The extent to which this might bias our findings is unclear. Facebook has updated and changed privacy setting options over the past few years, leaving many Facebook users confused and even angry at the complexity of the currently available settings [51–53]. People who are more familiar with Facebook may have been more likely to adjust privacy settings and more likely to exhibit problematic usage, potentially biasing our estimate downward, but this remains an empirical question. Finally, although the scale we used has been validated in adults, it may not be ideally suited to the adolescent or college student population. A distinct measure of problematic Internet usage is clearly needed for these age groups. In the interim, our estimate is probably conservative, given the nature of some of the questions asked. Furthermore, the individual domain analysis suggests that there is the potential for significant problematic usage among college students.

In spite of these limitations, the results of this pilot study have some important implications for college students and administrators. Problematic Internet usage is prevalent on US college campuses. Colleges should consider both preventative approaches in the form of awareness campaigns leveraging students' self-reported concerns about their usage of the Internet, and, for some students, treatment might even be warranted. Finally, given that Internet usage begins during early to middle childhood, pediatricians should make assessment of Internet usage a part of preventative practice [54].

References

Christakis DA, Moreno MA: Trapped in the net: will internet addiction become a 21st-century epidemic?. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009, 163: 959-960. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.162.

Block JJ: Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. Am J Psychiatry. 2008, 165: 306-307. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101556.

Aboujaoude E, Koran LM, Gamel N, Large MD, Serpe RT: Potential markers for problematic Internet use: a telephone survey of 2,513 adults. CNS Spectr. 2006, 11: 750-755.

Grant JE, Potenza MN, Weinstein A, Gorelick DA: Introduction to behavioral addictions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010, 36: 233-241. 10.3109/00952990.2010.491884.

Kaltiala-Heino R, Lintonen T, Rimpelä A: Internet addiction? Potentially problematic use of the Internet in a population of 12-18 year-old adolescents. Addict Res Theory. 2004, 12: 89-96. 10.1080/1606635031000098796.

Pallanti S, Bernardi S, Quercioli L: The Shorter PROMIS Questionnaire and the Internet Addiction Scale in the assessment of multiple addictions in a high-school population: prevalence and related disability. CNS Spectr. 2006, 11: 966-974.

Siomos KE, Dafouli ED, Braimiotis DA, Mouzas OD, Angelopoulos NV: Internet addiction among Greek adolescent students. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008, 11: 653-657. 10.1089/cpb.2008.0088.

Villella C, Martinotti G, Di Nicola M, Cassano M, La Torre G, Gliubizzi MD, Messeri I, Petruccelli F, Bria P, Janiri L, Conte G: Behavioural addictions in adolescents and young adults: results from a prevalence study. J Gambl Stud.

Zboralski K, Orzechowska A, Talarowska M, Darmosz A, Janiak A, Janiak M, Florkowski A, Gałecki P: The prevalence of computer and Internet addiction among pupils. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2009, 63: 8-12.

Ghassemzadeh L, Shahraray M, Moradi A: Prevalence of Internet addiction and comparison of Internet addicts and non-addicts in Iranian high schools. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008, 11: 731-733. 10.1089/cpb.2007.0243.

Canbaz S, Sunter AT, Peksen Y, Canbaz MA: Prevalence of the pathological Internet use in a sample of Turkish school adolescents. Iran J Public Health. 2009, 38: 64-71.

Canan F, Ataoglu A, Nichols LA, Yildirim T, Ozturk O: Evaluation of psychometric properties of the Internet Addiction Scale in a sample of Turkish high school students. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010, 13: 317-320. 10.1089/cyber.2009.0160.

Cao F, Su L: Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: prevalence and psychological features. Child Care Health Dev. 2007, 33: 275-281. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00715.x.

Deng YX, Hu M, Hu GQ, Wang LS, Sun ZQ: An investigation on the prevalence of Internet addiction disorder in middle school students of Hunan province in Chinese. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2007, 28: 445-448.

Ko CH, Yen JY, Yen CF, Lin HC, Yang MJ: Factors predictive for incidence and remission of Internet addiction in young adolescents: a prospective study. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007, 10: 545-551. 10.1089/cpb.2007.9992.

Park SK, Kim JY, Cho CB: Prevalence of Internet addiction and correlations with family factors among South Korean adolescents. Adolescence. 2008, 43: 895-909.

Song XQ, Zheng L, Li Y, Yu DX, Wang ZZ: Status of 'Internet addiction disorder' (IAD) and its risk factors among first-grade junior students in Wuhan. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2010, 31: 14-17. [in Chinese]

Wu J, Lin G, Lin L: Analysis of the situation of internet use and the related health-risky behaviors among the youngsters in Guangzhou City. J Trop Med (Guangzhou). 2007, 7: 816-818.

Xu J, Shen LX, Yan CH, Wu ZQ, Ma ZZ, Jin XM, Shen XM: Internet addiction among Shanghai adolescents: prevalence and epidemiological features. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008, 42: 735-738. [in Chinese]

Wang YL, Wang JP, Fu DD: Epidemiological investigation on Internet addiction among Internet users in elementary and middle school students. Chin Ment Health J. 2008, 22: 678-682.

Young KS, Rogers RC: The relationship between depression and Internet addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998, 1: 25-28. 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.25.

Young KS: Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998, 1: 237-244. 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237.

Scherer K: College life on-line: healthy and unhealthy Internet use. J Coll Stud Dev. 1997, 38: 655-665.

Lavin M, Marvin K, McLarney A, Nola V, Scott L: Sensation seeking and collegiate vulnerability to Internet dependence. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1999, 2: 425-430. 10.1089/cpb.1999.2.425.

Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P: Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Comput Human Behav. 2000, 16: 13-29. 10.1016/S0747-5632(99)00049-7.

Anderson KJ: Internet use among college students: an exploratory study. J Am Coll Health. 2001, 50: 21-26. 10.1080/07448480109595707.

Lavin MJ, Yuen CN, Weinman M, Kozak K: Internet dependence in the collegiate population: the role of shyness. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004, 7: 379-383. 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.379.

Fortson BL, Scotti JR, Chen YC, Malone J, Del Ben KS: Internet use, abuse, and dependence among students at a southeastern regional university. J Am Coll Health. 2007, 56: 137-144. 10.3200/JACH.56.2.137-146.

Niemz K, Griffiths M, Banyard P: Prevalence of pathological Internet use among university students and correlations with self-esteem, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), and disinhibition. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005, 8: 562-570. 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.562.

Zhu K, Wu H: Psychosocial factors of to Internet addiction disorder in college students. Chin Ment Health J. 2004, 18: 796-798.

Ni XL, Yan H, Chen S, Liu Z: Factors influencing Internet addiction in a sample of freshmen university students in China. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009, 12: 327-330. 10.1089/cpb.2008.0321.

Davis SF, Smith BG, Rodrigue K, Pulvers K: An examination of Internet usage on two college campuses. Coll Stud J. 1999, 33: 257-260.

DoubleClick Ad Planner by Google. [https://www.google.com/adplanner/planning/site_details#siteDetails?identifier=facebook.com&geo=US&trait_type=1&lp=false]

Facebook. [http://www.Facebook.com]

Pempek TA, Yermolayeva YA, Calvert SL: College students' social networking experiences on Facebook. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009, 20: 227-238.

Ross C, Orr ES, Sisic M, Arseneault JM, Simmering MG, Orr RR: Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Comput Hum Behav. 2009, 25: 578-586. 10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.024.

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C: The benefits of Facebook 'friends': social capital and college students' use of online social network sites. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2007, 12: 1143-1168. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x.

Lewis K, Kaufman J, Christakis N: The taste for privacy: an analysis of college student privacy settings in an online social network. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2008, 14: 79-100. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.01432.x.

Widyanto L, McMurran M: The psychometric properties of the Internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004, 7: 443-450. 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.443.

netaddiction.com. [http://www.netaddiction.com/]

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001, 16: 606-613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Zou G: A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 159: 702-706. 10.1093/aje/kwh090.

Lumley T, Kronmal R, Ma S: Relative risk regression in medical research: models, contrasts, estimators, and algorithms. University of Washington Biostatistics Working Paper Series: Working Paper 293, 19 July 2006, [http://www.bepress.com/uwbiostat/paper293/]

Settipane GA, Greisner WA, Settipane RJ: Natural history of asthma: a 23-year followup of college students. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000, 84: 499-503. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62512-4.

Hrubec Z, Omenn GS: Evidence of genetic predisposition to alcoholic cirrhosis and psychosis: twin concordances for alcoholism and its biological end points by zygosity among male veterans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1981, 5: 207-215. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1981.tb04890.x.

Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr : Social media and young adults. 2010, Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project, [http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Social-Media-and-Young-Adults.aspx]

Jang KS, Hwang SY, Choi JY: Internet addiction and psychiatric symptoms among Korean adolescents. J Sch Health. 2008, 78: 165-171. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00279.x.

Rømer Thomsen K, Callesen MB, Linnet J, Kringelbach ML, Møller A: Severity of gambling is associated with severity of depressive symptoms in pathological gamblers. Behav Pharmacol. 2009, 20: 527-536. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283305e7a.

Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CS, Yeh YC, Yen CF: Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for Internet addiction in adolescents: a 2-year prospective study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009, 163: 937-943. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.159.

Moreno Megan, Jelenchick Lauren, Cox Elizabeth, Young Henry, Dimitri Christakis: , Problematic Internet Use Among US Youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010, [http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/archpediatrics.2011.58]

A Special Report on Social Networking: Privacy 2.0: Give a Little, Take a Little. The Economist. 2010, [http://www.economist.com/node/15350984?story_id=15350984]

Lyons D: The High Price of Facebook: You Pay for It With Your Privacy. Newsweek. 2010, [http://www.newsweek.com/2010/05/15/the-high-price-of-facebook.html]

Fletcher D: How Facebook Is Redefining Privacy. Time. 2010, [http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1990582,00.html]

Christakis DA, Ebel BE, Rivara FP, Zimmerman FJ: Television, video, and computer game usage in children under 11 years of age. J Pediatr. 2004, 145: 652-656. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.078.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/77/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by award K12HD055894 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Child Health, Behavior and Development Institute and by award R21AA017936-01A1 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

DAC and MMM conceived of and designed the study. LJ administered the survey and collected the data. MTM and CZ were in charge of data analysis and were assisted by DAC and MMM. DAC, MMM and LJ drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Christakis, D.A., Moreno, M.M., Jelenchick, L. et al. Problematic internet usage in US college students: a pilot study. BMC Med 9, 77 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-77

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-77