Abstract

Background

Currently, diagnosis of affected individuals with rare genetic disorders can be lengthy and costly, resulting in a diagnostic odyssey and in many patients a definitive molecular diagnosis is never achieved despite extensive clinical investigation. The recent advent and use of genomic medicine has resulted in a paradigm shift in the clinical molecular genetics of rare diseases and has provided insight into the causes of numerous rare genetic conditions. In particular, whole exome and genome sequencing of families has been particularly useful in discovering de novo germline mutations as the cause of both rare diseases and complex disorders.

Case presentation

We present a six year old, nonverbal African American female with microcephaly, autism, global developmental delay, and metopic craniosynostosis. Exome sequencing of the patient and her two parents revealed a heterozygous two base pair de novo deletion, c.1897_1898delCA, p.Gln633ValfsX13 in ASXL3, predicted to result in a frameshift at codon 633 with substitution of a valine for a glutamine and introduction of a premature stop codon.

Conclusions

We provide additional evidence that, truncating and frameshifting mutations in the ASXL3 gene are the cause of a newly recognized disorder characterized by severe global developmental delay, short stature, microcephaly, and craniofacial anomalies. Furthermore, we expand the knowledge about disease causing mutations and the genotype-phenotype relationships in ASXL3 and provide evidence that rare, nonsynonymous, damaging mutations are not associated with developmental delay or microcephaly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obtaining a molecular diagnosis for many rare diseases can be an arduous task [1]. The process is often hindered by the rarity of conditions, which is further exacerbated by the clinical heterogeneity, genetic heterogeneity (genocopies) and phenocopies that rare diseases tend to exhibit [2]. Frequently, this results in a process that has been termed the diagnostic odyssey [3]. The NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research reported that it took 1 to 5 years to reach a proper diagnosis for 33% of patients with rare disorders and more than 5 years for 15% of these patients [4]. The recent advent and use of genomic medicine has resulted in a paradigm shift in the clinical molecular genetics of rare diseases – from phenotype-driven diagnosis to genotype-driven diagnosis – and has provided insight into the causes of numerous rare genetic conditions [1]. Briefly genomic medicine, defined as the structured approach to disease discovery, diagnosis, and management that prominently features next-generation sequencing and analysis at a genome scale [5], has provided the impetus for a paradigm shift in the clinical evaluation of rare diseases to identify underlying molecular genetic causes.

Whole exome and genome sequencing of families has been particularly useful in discovering de novo germline mutations as the cause of both rare diseases and complex disorders. For example, de novo mutations have recently been associated with multiple rare diseases including rare growth disorders characterized by megalencephaly due to mutations in three genes, AKT3, PIK3R2, PIK3CA, [6] and Baraitser-Winter syndrome, characterized by brain malformations due to de novo mutations in the actin genes ACTB and ACTG1[7]. We recently described a de novo mutation in MTOR as a cause of megalencephaly and intractable seizures (Smith et al., submitted). In addition, new research has implicated de novo mutations in the complex disorders of autism [8–10] and schizophrenia [11, 12].

First described in 1999, Bohring-Optiz syndrome (BOS) [OMIM, 605039] has recently been shown through the use of next-generation exome sequencing, to be due to de novo heterozygous mutations in the additional sex combs-like 1 gene (ASXL1) [13]. Two further cases of de novo mutations in ASXL1 in patients with BOS supported the disease-gene association and gave limited insight into genotype-phenotype relationships [14]. Prior to this, the presence of seven of ten features were needed for a clinical diagnosis: trigonocephaly, microcephaly, flammeus nevus, prominent eyes, micro- or retrognathia, abnormal palate, typical BOS posture, feeding difficulties, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and severe/profound learning difficulties [15].

Here, we report on the use of exome sequencing of a proband with considerable overlap with the BOS phenotype and her parents to discover a heterozygous frame shift variant in the additional sex combs-like 3, (ASXL3) gene. ASXL3 is in the same gene family as ASXL1 and mutations in ASXL3 appear to be associated with a disorder that is paralogous to BOS.

Case presentation

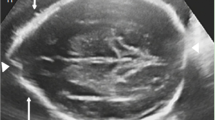

The proband is a 6 year old African American female (CMH000079) with microcephaly, autism, global developmental delay, and metopic craniosynostosis (Figure 1). She was born at 34-weeks gestation following a pregnancy complicated by insulin-dependent diabetes, with maternal blood sugar lability throughout pregnancy. The patient’s mother was a 30 year old gravida 3, para 2 female, with a history of 1 first trimester miscarriage. There was no exposure to alcohol, tobacco, or drugs. Delivery was via cesarean section for breech presentation. At birth the proband had a weight of 1.88 kg (25% for gestational age), length 40.5 cm (3% for gestational age), and occipitofrontal circumference 30 cm (25% for gestational age). Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at one and five minutes, respectively; however, on the first day of life she was transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) for hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia.

Family history was notable for a maternal half-sister with type 1 diabetes mellitus, who also had a history of hyperinsulinemia and hypoglycemic seizures in infancy, but who has normal cognitive functioning. The mother also had a history of hypoglycemia in childhood that evolved to insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. The mother is otherwise healthy and has no history of learning problems. The patient’s father has hypertension, but is otherwise healthy.

In the first 18 months of life the patient was hospitalized 10 times for vomiting, hypoglycemia, failure to thrive, and episodic irritability. Blood glucose was labile, ranging from 40–215 mg/dL (reference range 60–110 mg/dL). She had two hypoglycemic seizures. A sulfonylurea receptor defect was suspected because of the blood sugar lability in the proband, sister, and mother. Molecular testing of the proband and her mother identified a shared novel variant in the ABCC8 (ATP-Binding Cassette, Subfamily, Member 8) gene (c. 2143G > A; p.Val115Met) that was considered to be consistent with a diagnosis of Familial Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia Type 1 (HHF1 OMIM #256450) [16, 17]. She was therefore placed on diazoxide; a gastrostomy tube and a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line were placed for nutrition and glucose stabilization.

By 18 months, length and weight were between the 10-25th percentiles but head circumference was below the 3rd percentile. She was hypotonic and hyperreflexic. She had dysmorphic facial features including a sloping forehead with metopic ridging, a flat nasal bridge, wide-set eyes and slightly posteriorly rotated ears. The nose had a short columella and hypoplastic alae nasae. Nasolabial folds were smooth and the upper lip had a prominent Cupid’s bow. She had no other dysmorphic features. Developmental milestones were delayed. At 18 months, she could army crawl, had inconsistent visual attention, and was nonverbal. She had episodic irritability with fits of screaming lasting hours, self-injurious behavior, and very poor sleep. She developed repetitive movements, predominately lateral head shaking. Developmental testing demonstrated delay: on the Cognitive Adaptive Test [18], her visual-motor/problem-solving quotient was 33 (mean 100, SD 10); on the Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale [18], language quotient was 42 (mean 100, SD 10). Brain MRI demonstrated mild white matter loss with enlarged lateral ventricles and mild prominence of the sulci. Brain spectroscopy was normal. A head CT confirmed suspected metopic synostosis. Surgical correction of synostosis resulted in less irritability, but did not affect development. An echocardiogram was notable for mild pulmonary artery stenosis, an aortopulmonary collateral vessel, and a small patent foramen ovale. Because of the differences in her development and phenotype from those of her mother and sister, who share the HHF1 diagnosis, additional genetic testing was obtained. Karyotype, microarray, FMR1 gene analysis, MECP2 sequencing, and MECP2 deletion/duplication testing were normal. She remained nonverbal, microcephalic, and globally delayed with repetitive motor behaviors and was diagnosed with autism. She began to walk at around 3 years of age. Through age 6, she continued to be a diagnostic enigma. Several, but not all, of these features have been reported in BOS (Table 1).

At age 6, the proband and her parents were enrolled in an undiagnosed disease program at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in which trios undergo a research exome sequencing study. Briefly, DNA isolated from peripheral blood cells was enriched for all coding exons, UTR, and promoter regions in more than 20,000 characterized genes using the Illumina TruSeq exome enrichment kit and sequenced 2x101 base pairs on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument (Additional file 1: Methods). Alignment and variant characterization were conducted as stated in the Supplement and previously described [19, 20]. The patient’s exome was analysed as a trio (two healthy parents and one affected child) for potential mitochondrial [19], de novo dominant, and autosomal recessive causes of disease. Zero rare (defined as frequency of 1% or less in dbSNP v137 [21], the 1,000 Genomes Project [22] or CPGM internal variant database [19, 20]), likely pathogenic mitochondrial variants were discovered. However, CMH00079 was found to be heterozygous for two apparent de novo mutations. A nonsynonymous de novo mutation in VAX1 (c.267C > G, p.Ile89Met) and a two base pair de novo deletion, c.1897_1898delCA (p.Gln633ValfsX13) in ASXL3, predicted to result in a frameshift at codon 633 with substitution of a valine for a glutamine and introduction of a premature stop codon 13 amino acids downstream were discovered (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The ASXL3 deletion was seen in 41 of 90 reads covering the region in CMH000079, but not observed in the mother, CMH000080, or father, CMH000081, despite adequate sequence coverage at that nucleotide (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Heterozygous de novo truncating variants in ASXL3 have recently been reported in 4 patients with a novel clinical phenotype similar to Bohring-Opitz syndrome, and are consistent with this patient’s clinical findings (Table 1, [23]). In addition, two, rare, nonsynonymous, compound heterozygous mutations were also discovered in LYST (c.597C > G; p.Asp199Glu & c.298C > T; p.Leu100Phe). After expert review the variants in VAX1 and LYST were deemed unlikely to be pathogenic as the patient did not fit clinical or genetic descriptions of syndromic Microphthalmia type 11 (OMIM, 604294), which is an autosomal recessive disorder with prominent microphtalmia (not seen in our patient) or Chediak-Higashi syndrome (OMIM, 606897), a primary immunodeficiency with partial albinism, leaving the de novo mutation in ASXL3 as the highest candidate disease causing mutation. Of note, analysis of ASXL1 revealed two non-pathogenic inherited variants and zero de novo mutations, ruling out Bohring-Optiz syndrome. The ASXL3 mutation was confirmed by capillary sequencing in a clinical lab prior to reporting to the family (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

To better understand the rare, nonsynonymous variant burden and impact of mutations in the ASXL3 gene, we examined the number of variants of a frequency of less than 1% in the ASXL3 gene in the CPGM internal variant database [19, 20]. This database collates every variant detected at the CPGM including the frequency of occurrence and associated clinical phenotypes. The database contains children with suspected rare genetic disorders as well as healthy unaffected family members. In the more than 1,300 exomes sequenced at the CPGM, the proband is the only patient with a heterozygous frameshift mutation in ASXL3, predicting a truncated gene product. However, there are 29 single nucleotide variants of with a frequency of less than 1 percent in our database (Additional file 1: Table S1). Characterization of these 29 rare variants revealed 19 that were predicted to deleterious by SIFT (Sorts Intolerant From Tolerant substitutions) [24] and 11 predicted to be probably or possibly damaging by PolyPhen2 (Polymorphism Phenotyping 2) [25]. Phenotypic evaluation of the samples with these rare, non-synonymous variants revealed no patients with developmental delay, microcephaly, or other craniofacial anomalies, suggesting that these variants are unlikely to be pathogenic in a heterozygous state.

Discussion

In this study we provide the second report and fifth patient with pathogenic mutations in ASXL3. Our case provides additional evidence that, indeed, truncating frameshift mutations in the ASXL3 gene are the cause of a newly recognized distinct disorder characterized by global developmental delay and craniofacial anomalies that shares significant clinical features with Bohring-Opitz syndrome. Our patient, CMH000076, exhibited multiple overlapping clinical features of BOS, most notably trigonocephaly, microcephaly, feeding difficulties, and severe learning difficulties (Table 1). Unlike the previously reported cases with ASXL3 mutations, our patient had trigonocephaly, thus, the lack of trigoncephaly may not be a useful in differentiating BOS from this newly recognized condition [23]. To date, none of the five patients described with ASXL3 mutations has displayed the typical BOS-posture, whereas 100 percent of the 30 described patients with ASXL1 mutations did [14], suggesting that this feature might be useful in discriminating between the two related conditions.

The mutation in our patient was at amino coding position 633, which is closest to subject #3 reported by Bainbridge et al. [23] (659_660del). In contrast to subject #3, however, CMH000079 exhibited a severe phenotype with feeding difficulties, growth restriction and severe global developmental delay. Both the mutation described here and that of the previously described subject #3 occur in an evolutionarily conserved serine-rich motif found between residues ~600-800 [23]. The considerable clinical variability between our patient and that of subject #3 emphasize the need for additional studies of the complex phenotype-genotype associations in this disorder and the paralogous disorder BOS. The diagnosis of HHF1 due to mutation in ABCC8 in this patient likely contributed to her recurring hospitalizations and growth difficulties, and may have impacted her early development. Importantly, the ABCC8 variant (c. 2143G > A; p.Val115Met) was also identified by the whole exome sequencing. Labile maternal blood glucose during pregnancy was also considered in the early differential of her developmental delay. However, both the mother and sister of the proband share HHF1 diagnosis and have histories of severe hypoglycemia and with resultant episodes of altered mental status and seizures in early childhood; both have normal cognitive functioning and achieved normal growth parameters.

To date, all reported potential pathogenic mutations in ASXL3 have been either frameshifting or truncating [23]. To further examine the variant burden in ASXL3 and the genotype-phenotype relationship, we utilized our clinical grade variant database with more than 1,300 exomes to evaluate rare variation (defined as present in less than 1% of samples) in the ASXL3 gene. Unlike what has been reported in other large-scale databases, our internal warehouse does not contain samples with truncating, nonsense mutations [23]; however we did uncover 29 rare, single nucleotide variants (SNVs) (Additional file 1: Table S1). ASXL3 is 6,747 nucleotides long and composed of 12 exons with the 3’ exons 11 and 12 being disproportionately large; comprising 1,957 and 3,708 nucleotides, respectively. The vast majority of the variants from our database were in exon 11, which included our de novo deletion or exon 12 (Additional file 1: Table S1). Interestingly, although our database contains 107 samples with neurodevelopmental disorders, none of the discovered rare variants were in any of these patients, suggesting that these variants are unlikely to be pathogenic in a heterozygous state and providing additional support that only frameshifting or truncating mutations in ASXL3 are pathogenic. However, additional functional studies to investigate the pathogenicity of ASXL3 variants are needed to completely conclude that SNVs are expected to be nonpathogenic.

Conclusions

In summary, we describe the use of familial exome sequencing to discover a de novo framshift mutation in the ASXL3 gene in a patient with feeding difficulties, microcephaly, severe global developmental delay, and craniofacial anomalies. Furthermore, we provide additional evidence that heterozygous, frameshift, truncating mutations in ASXL3 are the cause of a newly recognized disorder [23]. In addition, we expand the knowledge about disease causing mutations and the genotype-phenotype relationships in ASXL3 and provide evidence that rare, nonsynonymous, and predicted damaging mutations are not associated with developmental delay or microcephaly, rather that pathogenic are likely to be either frameshifting or truncating.

Consent

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children’s Mercy Hospital (CMH). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Abbreviations

- ASXL1:

-

Additional sex combs-like 1

- ASXL3:

-

Additional sex combs-like 3

- BOS:

-

Bohring-Optiz syndrome

- CPGM:

-

Center for pediatric genomic medicine

- CMH:

-

Children’s mercy hospital

- HHF1:

-

Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, familial, type 1

- IUGR:

-

Intrauterine growth restriction

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PICC:

-

Peripherally inserted central catheter

- PolyPhen2:

-

Polymorphism phenotyping 2

- SIFT:

-

Sorts intolerant from tolerant substitutions

- SNVs:

-

Single nucleotide variants.

References

Gahl WA, Markello TC, Toro C, Fajardo KF, Sincan M, Gill F, Carlson-Donohoe H, Gropman A, Pierson TM, Golas G, et al: The national institutes of health undiagnosed diseases program: insights into rare diseases. Genet Med. 2012, 14 (1): 51-59. 10.1038/gim.0b013e318232a005.

Zori RT, Williams CA: Phenocopy versus genocopy. Am J Med Genet . 1991, 40 (2): 248-249. 10.1002/ajmg.1320400224.

Exe N, Heather-Ferguson MS, Alyson Krokosky CGC, Sawyer S, Sharon Terry MA: Genetic Testing Stories. 2006, Washington (DC): Genetic Alliance Monograph Series, “http://www.geneticalliance.org/” Genetic Alliance

Gahl WA, Tifft CJ: The NIH undiagnosed diseases program: lessons learned. JAMA. 2011, 305 (18): 1904-1905. 10.1001/jama.2011.613.

Green ED, Guyer MS, National Human Genome Research I: Charting a course for genomic medicine from base pairs to bedside. Nature. 2011, 470 (7333): 204-213. 10.1038/nature09764.

Riviere JB, Mirzaa GM, O’Roak BJ, Beddaoui M, Alcantara D, Conway RL, St-Onge J, Schwartzentruber JA, Gripp KW, Nikkel SM, et al: De novo germline and postzygotic mutations in AKT3, PIK3R2 and PIK3CA cause a spectrum of related megalencephaly syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012, 44 (8): 934-940. 10.1038/ng.2331.

Riviere JB, van Bon BW, Hoischen A, Kholmanskikh SS, O’Roak BJ, Gilissen C, Gijsen S, Sullivan CT, Christian SL, Abdul-Rahman OA, et al: De novo mutations in the actin genes ACTB and ACTG1 cause baraitser-winter syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012, 44 (4): 440-444. 10.1038/ng.1091. S441-442

Michaelson JJ, Shi Y, Gujral M, Zheng H, Malhotra D, Jin X, Jian M, Liu G, Greer D, Bhandari A, et al: Whole-genome sequencing in autism identifies hot spots for de novo germline mutation. Cell. 2012, 151 (7): 1431-1442. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.019.

Neale BM, Kou Y, Liu L, Ma’ayan A, Samocha KE, Sabo A, Lin CF, Stevens C, Wang LS, Makarov V, et al: Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2012, 485 (7397): 242-245. 10.1038/nature11011.

O’Roak BJ, Vives L, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Krumm N, Coe BP, Levy R, Ko A, Lee C, Smith JD, et al: Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012, 485 (7397): 246-250. 10.1038/nature10989.

Rees E, Kirov G, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ: De novo mutation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012, 38 (3): 377-381. 10.1093/schbul/sbs047.

Xu B, Ionita-Laza I, Roos JL, Boone B, Woodrick S, Sun Y, Levy S, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M: De novo gene mutations highlight patterns of genetic and neural complexity in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2012, 44 (12): 1365-1369. 10.1038/ng.2446.

Hoischen A, van Bon BW, Rodriguez-Santiago B, Gilissen C, Vissers LE, de Vries P, Janssen I, van Lier B, Hastings R, Smithson SF, et al: De novo nonsense mutations in ASXL1 cause Bohring-Opitz syndrome. Nat Genet. 2011, 43 (8): 729-731. 10.1038/ng.868.

Magini P, Della Monica M, Uzielli ML, Mongelli P, Scarselli G, Gambineri E, Scarano G, Seri M: Two novel patients with Bohring-Opitz syndrome caused by de novo ASXL1 mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2012, 158A (4): 917-921. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35265.

Hastings R, Cobben JM, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Goodship J, Hove H, Kjaergaard S, Kemp H, Kingston H, Lunt P, Mansour S, et al: Bohring-Opitz (oberklaid-danks) syndrome: clinical study, review of the literature, and discussion of possible pathogenesis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011, 19 (5): 513-519. 10.1038/ejhg.2010.234.

Babenko AP, Polak M, Cave H, Busiah K, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L, Vaxillaire M, Froguel P: Activating mutations in the ABCC8 gene in neonatal diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355 (5): 456-466. 10.1056/NEJMoa055068.

Ugrasbul F, Jacobson J: Dominantly inherited mutation in SUR1 (ABCC8 gene) associated with congenital hyperinsulinism and diabetes later in life. 2007, Toronto, Canada: Poster session presented at: Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society Annual Meeting, 4-7.

Voigt RG, Brown FR, Fraley JK, Llorente AM, Rozelle J, Turcich M, Jensen CL, Heird WC: Concurrent and predictive validity of the cognitive adaptive test/clinical linguistic and auditory milestone scale (CAT/CLAMS) and the mental developmental index of the bayley scales of infant development. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2003, 42 (5): 427-432. 10.1177/000992280304200507.

Dinwiddie DL, Smith LD, Miller NA, Atherton AM, Farrow EG, Strenk ME, Soden SE, Saunders CJ, Kingsmore SF: Diagnosis of mitochondrial disorders by concomitant next-generation sequencing of the exome and mitochondrial genome. Genomics. 2013, 102 (3): 148-156. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.04.013.

Saunders CJ, Miller NA, Soden SE, Dinwiddie DL, Noll A, Alnadi NA, Andraws N, Patterson ML, Krivohlavek LA, Fellis J, et al: Rapid whole-genome sequencing for genetic disease diagnosis in neonatal intensive care units. Sci Transl Med. 2012, 4 (154): 154ra135-10.1126/scitranslmed.3004041.

Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, Sirotkin K: dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29 (1): 308-311. 10.1093/nar/29.1.308.

Genomes Project C, Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA: An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012, 491 (7422): 56-65. 10.1038/nature11632.

Bainbridge MN, Hu H, Muzny DM, Musante L, Lupski JR, Graham BH, Chen W, Gripp KW, Jenny K, Wienker TF, et al: De novo truncating mutations in ASXL3 are associated with a novel clinical phenotype with similarities to Bohring-Opitz syndrome. Genome Med. 2013, 5 (2): 11-10.1186/gm415.

Ng PC, Henikoff S: SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (13): 3812-3814. 10.1093/nar/gkg509.

Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR: A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010, 7 (4): 248-249. 10.1038/nmeth0410-248.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1755-8794/6/32/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the family for participating in this research and allowing us to share the findings and Drs. Matthew N. Bainbridge, Jill Jacobson and Figen Ugrasbul-Eskinar for discussions. A Deo lumen, ab amicis auxilium.

Funding

This work was funded by the Marion Merrell Dow Foundation, the Patton Trust, the WT Kemper Foundation, and the Children’s Mercy Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualized and designed the study SFK. Drafted the initial manuscript: DLD, SES. Coordinated and supervised sample and clinical data collection, obtained consent: SES, LDS. Undertook the exome sequencing: DLD, EGF. Designed the bioinformatics tools, and coordinated bioinformatics efforts: NAM. Carried out the initial analyses: DLD. Reviewed data analysis and oversaw clinical reporting of genetic findings: CJS. Developed clinical-pathological components of bioinformatic tools, and coordinated protocol implementation: NAM, SES. Reviewed and revised the manuscript: SFK, LDS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Darrell L Dinwiddie, Sarah E Soden contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12920_2013_412_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Methods. Figure S1. Next-generation sequencing results viewed in the Integrative Genome Viewer [12] of the de novo frameshifting mutation 1897_1898delCA, p.Gln633ValfsX13 in CMH000079 and not present in mother (CMH000080) or father (CMH000081). Figure S2. Capillary sequencing results of the de novo frameshifting mutation 1897_1898delCA, p.Gln633ValfsX13 in patient with forward and reverse PCR primers and control sample. Table S1. Variants at a frequency of less than 1% in ASXL3 more than 1,300 exomes sequenced at the Center for Pediatric Genomic Medicine at Children’s Mercy Hospital. (DOCX 564 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dinwiddie, D.L., Soden, S.E., Saunders, C.J. et al. De novoframeshift mutation in ASXL3 in a patient with global developmental delay, microcephaly, and craniofacial anomalies. BMC Med Genomics 6, 32 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-8794-6-32

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-8794-6-32