Abstract

Introduction

SPARC is a matricellular protein, which, along with other extracellular matrix components including collagens, is commonly over-expressed in fibrotic diseases. The purpose of this study was to examine whether inhibition of SPARC can regulate collagen expression in vitro and in vivo, and subsequently attenuate fibrotic stimulation by bleomycin in mouse skin and lungs.

Methods

In in vitro studies, skin fibroblasts obtained from a Tgfbr1 knock-in mouse (TBR1CA; Cre-ER) were transfected with SPARC siRNA. Gene and protein expressions of the Col1a2 and the Ctgf were examined by real-time RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. In in vivo studies, C57BL/6 mice were induced for skin and lung fibrosis by bleomycin and followed by SPARC siRNA treatment through subcutaneous injection and intratracheal instillation, respectively. The pathological changes of skin and lungs were assessed by hematoxylin and eosin and Masson's trichrome stains. The expression changes of collagen in the tissues were assessed by real-time RT-PCR and non-crosslinked fibrillar collagen content assays.

Results

SPARC siRNA significantly reduced gene and protein expression of collagen type 1 in fibroblasts obtained from the TBR1CA; Cre-ER mouse that was induced for constitutively active TGF-β receptor I. Skin and lung fibrosis induced by bleomycin was markedly reduced by treatment with SPARC siRNA. The anti-fibrotic effect of SPARC siRNA in vivo was accompanied by an inhibition of Ctgf expression in these same tissues.

Conclusions

Specific inhibition of SPARC effectively reduced fibrotic changes in vitro and in vivo. SPARC inhibition may represent a potential therapeutic approach to fibrotic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fibrosis is a general pathological process in which excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) occurs in the tissues. It is currently untreatable. Although therapeutic uses of some anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents such as colchicine, interferon-gamma, corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide have been reported, many of these approaches have not proven successful [1–3]. Recently, SPARC (secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteine), a matricellular component of the ECM, has been reported as a bio-marker for fibrosis in multiple fibrotic diseases, such as interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, renal interstitial fibrosis, cirrhosis, atherosclerotic lesions and scleroderma or systemic sclerosis (SSc) [4–9]. Notably, increased expression of SPARC has been observed in affected skin and circulation of patients with SSc [10, 11], a devastating disease of systemic fibrosis, as well as in cultured dermal fibroblasts obtained from SSc skin [8, 9].

SPARC, also called osteonectin or BM-40, is an important mediator of cell-matrix interaction [12]. Increasing evidence indicates that SPARC may play an important role in tissue fibrosis. In addition to its higher expression level in the tissues of fibrotic diseases, SPARC has shown a capacity to stimulate the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling system [13]. Inhibition of SPARC attenuates the profibrotic effect of exogenous TGF-β in cultured human fibroblasts [14]. Moreover, in animal studies, SPARC-null mice display a diminished amount of pulmonary fibrosis compared with control mice after exposure to bleomycin, a chemotherapeutic antibiotic with a profibrotic effect [15]. These observations suggest that SPARC is a potential bio-target for anti-fibrotic therapy.

Recently, application of double-stranded small interfering RNA (siRNA) to induce RNA silencing in cells has been widely accepted in many studies of gene functions and potential therapeutic targets [16]. The selective and robust effect of RNAi on gene expression makes it a valuable research tool, both in cell culture and in living organisms. Unlike a gene knockout method, siRNA-based technology can easily silence the expression of a specific gene and is more feasible in practice, such as in disease therapy. Therefore, tissue-specific administration of the siRNA of candidate genes is currently being developed as a potential therapy in a great number of diseases, such as pulmonary diseases, ocular diseases, and others [17–19]. Our previous studies demonstrated that the overproduction of collagens in the fibroblasts obtained from SSc skin can be attenuated through SPARC silencing with siRNA. It suggested that application of SPARC silencing represents a potential therapeutic approach to fibrosis in SSc and other fibrotic diseases [20]. However, it is still unknown whether SPARC siRNA can improve fibrotic manifestations in vivo. The main purpose of the studies herein was to explore the feasibility of inhibition of SPARC with siRNA to counter fibrotic processes in a fibrotic mouse model in vivo. As a preliminary experiment in the in vivo studies, the fibroblasts cultured from a transgenic fibrotic model were used to assess the possibility and potential mechanisms of SPARC siRNA in attenuating the collagen expression in vitro. At the same time, the effects of SPARC siRNA to encounter fibrosis were compared with that of siRNA of CTGF, a well-known fibrotic marker. The fibrotic models used herein were the very popular bleomycin-induced skin and pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Subcutaneous injection and intratracheal instillation of siRNAs were used for tissue-specific treatments of skin and pulmonary fibrosis, respectively.

Materials and methods

Fibroblast cell lines from Tgfbr1 knock-in mouse

Constitutively activated Tgfbr1 mice, which recapitulated clinical, histological, and biochemical features of human SSc, have been reported previously [21]. They are termed TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice and harbor both the DNA for an inducible constitutively active TGFβ receptor I (TGFβRI) mutation targeted to the ROSA locus, and a Cre-ER transgene driven by a Col1 fibroblast-specific promoter. Fibroblasts were derived from skin biopsy specimens of these mice. The cultures were maintained in DMEM with 10% FCS and supplemented with antibiotics (50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin). Fifth-passage fibroblast cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells in 25-cm2 flasks and grown until confluence. Experiments were performed in triplicates.

Transient transfection with siRNA in fibroblasts

Double-stranded ON-TARGETplus siRNAs of murine SPARC and Ctgf were purchased from Dharmacon, Inc. (Lafayette, CO, USA). The corresponding target sequences are 5'-GCACCACACGUUUCUUUG-3' for SPARC and 5'-GCACCAGUGUGAAGACAUA-3' for Ctgf, respectively. The culture medium in each culture flask with confluent fibroblasts was replaced with Opti-MEM I medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) without FCS and antibiotics. The fibroblasts were incubated for 24 hours and transfected with SPARC siRNA or Ctgf siRNA in a concentration of 100 nmol/L, using DharmaFECT™ 1 siRNA Transfection Reagent (Dharmacon). Fibroblasts with Non-Targeting siRNA (Dharmacon) treatment were used as negative controls. The non-targeting siRNA was characterized by genome-wide microarray analysis and found to have minimal off-target signatures to human cells. It targets firefly luciferase (U47296). After 24 hours, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM. The cells transfected with siRNA were examined after 72 hours of transfection and used for RNA and protein expression analysis. The experiments were performed in triplicates.

Animal models of fibrosis

C57BL/6 mice of about 20 grams were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Bleomycin from Teva Parenteral Medicines Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA) was dissolved in saline and used in the mice at a concentration of 3.5 units/kg. Pulmonary fibrosis was induced in these mice with one time intratracheal instillation of bleomycin. For dermal fibrosis, female C57BL/6 mice at six weeks (weighing about 20 g) were treated daily for four weeks with local subcutaneous injection of 100 μl bleomycin in the shaved lower back. Four mice were used in each group. The animal protocols were approved by the Center for Laboratory Animal Medicine and Care in the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, and Fudan University, China.

Administration of siRNAs in vivo

For pulmonary fibrosis, 3 μg of siRNA for in vivo use (siSTABLE, Dharmacon), mixed with DharmaFECT™ 1 siRNA Transfection Reagent, was administrated intratracheally in 60 μl on Days 2, 5, 12 after bleomycin treatment. In addition, the siGLO Green transfection indicator (Dharmacon), a fluorescent RNA duplex was used for evaluating distribution of intratracheally injected siRNA. Twenty-four hours after injection, lung tissues were obtained for processing slides using a cryo-microtomy. All the mice were sacrificed on Day 23 after anesthesia, and the lung samples were collected. The left lungs were fixed by 4% formalin and used for further histological analysis. The right lungs were minced to small pieces and divided into two parts, one for RNA extraction and one for collagen content analysis.

For dermal fibrosis, the above siRNAs were injected into the same area as that of bleomycin three hours after bleomycin treatment and continued for four weeks. The mice were sacrificed on Day 29 and the skin samples were collected. Saline was used as a negative control in both fibrosis studies.

Determination of gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from each cell line was extracted from the cultured fibroblasts using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). For mice lung and skin tissues, the minced samples were homogenized in lysis solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with a blender. Then total RNA was extracted using GenElute™ Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using MultiScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using an ABI 7900 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems). The specific primers and probes for each gene (Col1a2, Col3A1, Ctgf, SPARC and Ccl2) were purchased from the Assays-on-Demand product line (Applied Biosystems). Synthesized cDNAs were mixed with primers/probes in 2 × TaqMan universal PCR buffer and then assayed on an ABI 7900 sequence detector. The data obtained from the assays were analyzed with SDS 2.2 software (Applied Biosystems). The expression level of each gene in each sample was normalized with Gapdh transcript level.

Western blot analysis

The lysis buffer for Western blot analysis consisted of 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Deoxycholate Acid, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA in PBS and proteinase inhibitor cocktail from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). The cellular lysates extracted from the cultured fibroblasts were used for protein assays. The protein concentration was determined by a spectrophotometer using Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein from each sample were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Resolved proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes and incubated with respective primary antibodies, including anti-type I collagen antibody (Biodesign International, Saco, ME, USA), anti-CTGF antibody (GeneTex Inc, San Antonio, TX, USA), and anti-SPARC antibody (R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Mouse β-actin (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA, USA) was used as an internal control. The secondary antibody was peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-goat, or anti-mouse IgG. Specific proteins were detected by chemiluminescence using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The intensity of the bands was quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Determination of collagen content

Non-crosslinked fibrillar collagen in lung samples and skin samples was measured using the Sircol colorimetric assay (Biocolor, Belfast, UK). Minced tissues were homogenized in 0.5 M acetic acid with about 1:10 ratio of pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissues were weighted, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with vigorous stirring. Digested samples were centrifuged and the supernatant was used for the analysis with the Sircol dye reagent. The protein concentration was determined using Bradford protein assay kits and the collagen content of each sample was normalized to total protein.

Histological analysis

The tissue samples of both lung and skin were fixed in 4% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm were stained either with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Masson's trichrome.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SD). The difference between different conditions or treatments was assessed by Student's t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Gene and protein expression of Col1a2, Ctgf and SPARC in the fibroblasts from TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice with and without transfection of siRNAs of SPARCor Ctgf

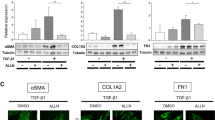

As measured by quantitative real-time RT-PCR, the transcripts of Col1a2, Ctgf and SPARC showed increased expression in the fibroblasts from TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice injected with 4-OHT, in which Tgfbr1 was constitutively active, compared with those in the cells from TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice injected with oil (Figure 1). The fold-changes of each gene in 4-OHT-injected TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice fibroblasts were 3.06 ± 1.42 for Col1a2 (P = 0.050), 4.15 ± 1.18 for Ctgf (P = 0.049), and 2.49 ± 0.63 for SPARC (P = 0.017), respectively. To study whether inhibition of SPARC induced a reduction of collagen in the fibroblasts from constitutively active Tgfbr1 mice, we transfected SPARC siRNA into cultured fibroblasts obtained from TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice injected with 4-OHT. Ctgf is a down-stream gene in the TGF-β pathway [22–25], and inhibition of Ctgf reduced expression of the fibrotic effect of TGF-β [26]. We used Ctgf siRNA as a positive control for inhibition of Ctgf and collagen expression. Transfection efficiency of siRNAs into fibroblasts was measured using fluorescent RNA duplex siGLO Green transfection indicator (Dharmacon) and was determined to be over 80%. The gene expression levels from the Non-Targeting siRNA treated fibroblasts were compared with those from saline-treatment fibroblasts, and no significant differences were found (1.05 ± 0.18-folds for Col1a2, 1.14 ± 0.16-folds for Ctgf, and 1.12 ± 0.12-folds for SPARC). Therefore, in the following in vitro study, fibroblasts with Non-Targeting siRNA treatment were used as negative controls. Seventy-two hours after SPARC siRNA or Ctgf siRNA transfection, significant reductions of SPARC (95%) by SPARC siRNA and Ctgf (64%) by Ctgf siRNA were observed in the fibroblasts (Figure 2A). In parallel, Col1a2 showed decreased expression in both siRNA transfected fibroblasts (27% and 29% decrease with P < 0.05 for Ctgf siRNA and SPARC siRNA, respectively) (Figure 2A). Western blot analysis showed a similar level of protein reduction of type I collagen by either SPARC siRNA or Ctgf siRNA treatment. As illustrated in Figure 2B, C, both SPARC siRNA and Ctgf siRNA showed significant attenuation of collagen type I in the fibroblasts (P = 0.009 or 0.015, respectively). CTGF and SPARC protein levels also were reduced by their corresponding siRNAs (P = 0.002 and 0.0004, respectively).

Comparison of gene expression between the fibroblasts of TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice injected with oil and 4-OHT. The expression level of each gene in the fibroblasts of TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice injected with oil was normalized to 1. Bars show the mean ± SD results of analysis of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.05.

Gene and protein expression in original and siRNA treated fibroblasts from TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice injected with 4-OHT. (A) Relative transcript levels of Col1a2, Ctgf, and SPARC in cultured fibroblasts transfected with non-targeting siRNA (NT siRNA), Ctgf siRNA and SPARC siRNA. The expression level of each gene in the fibroblast lines with NT siRNA transfection was normalized to 1. *, P < 0.05. (B) Western blot analysis of type I collagen (COL1), CTGF, and SPARC in the fibroblasts from constitutively active Tgfbr1 mice transfected with NT siRNA, Ctgf siRNA or SPARC siRNA. N, non-targeting siRNA transfected fibroblasts; C, Ctgf siRNA transfected fibroblasts; S, SPARC siRNA transfected fibroblasts. (C) Densitometric analysis of Western blots for protein level of COL1, CTGF, and SPARC. Compared to non-targeting siRNA treatment, Ctgf siRNA or SPARC siRNA transfected fibroblasts showed significant reduction of COL1 (P = 0.015 or 0.009 respectively). Significant reduction of CTGF (P = .002) by Ctgf siRNA and SPARC (P = 0.0004) by SPARC siRNA were also shown. Bars show the mean ± SD results of analysis of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.05.

siRNAs of SPARCand Ctgf ameliorated fibrosis in skin and reduced inflammation in lungs induced by bleomycin

HE stains of mouse skin tissues (Figure 3-1) showed that four-week injections of bleomycin induced significant fibrosis in skin where the fat cells were replaced by fiber bundles (Figure 3-1B, compared with normal skin injected with saline only (Figure 3-1A). Bleomycin-injected skin treated with SPARC siRNA or Ctgf siRNA showed that most of the fat cells still existed in the dermis without prominent fiber bundles (Figure 3-1C, D). Masson's trichrome staining of the samples also showed the same results. Notably, increased hair follicles were inconsistently seen in Ctgf siRNA- and SPARC siRNA-treated bleomycin-induced skins.

Examination of skin tissues. (1) Representative histological analysis of HE and Trichrome stain of mouse skin with different treatments for four weeks in low (4 ×) and high magnifications (20 ×). Four mice were used for each group. A. Injection with saline (negative control) only; B. Injection with bleomycin only; C. Injection with bleomycin and treatment with SPARC siRNA; D. Injection with bleomycin and treatment with Ctgf siRNA. (2) Collagen contents in skin samples with different treatments. The collagen content in the skin sample from saline treated mice was normalized to 1. Treatments: Sa, saline; B, bleomycin; B + C, bleomycin and Ctgf siRNAs; B + S, bleomycin and SPARC siRNA. P < 0.05.

The lung distribution of intratracheally injected fluorescent siRNA showed that intense fluorescence was distributed within epithelial cells of bronchi and bronchioles, and only weak fluorescence was detected in the parenchyma (Figure 4-1).

Examination of lung tissues. (1) The lung tissue staining for intratracheally injected fluorescent siRNA. Intense fluorescence was observed within epithelial cells of bronchi and bronchioles, and weak fluorescence was detected in the parenchyma. (2) Representative histological features of HE and Trichrome stain of mouse lung samples with different treatments intratracheally in low (4 ×) and high magnifications (40 ×). Four mice were used for each group. A. Injection with saline (negative control) only; B. Injection with bleomycin only on Day 0; C. Injection with bleomycin on Day 0 and SPARC siRNA on Days 2, 5, and 12; D. Injection with bleomycin on Day 0 and Ctgf siRNA on Days 2, 5, and 12. (3) Collagen contents in lung samples with different treatments. The collagen content in the lung sample from saline treated mice was normalized to 1. Four mice were used for each group. Treatments: Sa, saline; B, bleomycin; B + C, bleomycin and Ctgf siRNAs; B + S, bleomycin and SPARC siRNA. *, P < 0.05.

HE stain of mouse lung tissues (Figure 4-2) showed a significant disruption of the alveolar units and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lungs induced by bleomycin (Figure 4-2B), compared with saline injection (Figure 4-2A). However, after treatment with Ctgf siRNA or SPARC siRNA, the disruption of the alveoli was improved with less infiltrating inflammatory cells (Figure 4-2C, D). In addition, both siRNA treatments showed a significant reduction of gene expression of Ccl2, an active biomaker of inflammation, which was up-regulated in bleomycin stimulated mice (Figure 5B).

Gene expression in skin (A) or lung samples (B) with different treatments. Four mice were used for each treatment. The relative transcript levels of Col1a2, Col3a1, Ctgf, SPARC and Ccl2 in siRNA-treated or untreated bleomycin-induced skins or lungs, respectively. The expression level of each gene in the skin or lung sample from saline treated mice was normalized to 1. Treatments: Saline; BLM (bleomycin); BLM + Ctgf siRNA and BLM + SPARC siRNA. *, P < 0.05.

siRNAs of SPARCand Ctgf reduced the collagen contents in bleomycin-induced mouse skin and lung tissues

To further evaluate anti-fibrotic effects of siRNAs on the fibrogenesis of skin and lung, the collagen content was measured in the collected dermal and pulmonary samples. Quantification of total collagen in skin samples with the Sircol assay showed a 2.2-fold increase in bleomycin-induced skin compared with saline-injected skin (P = 0.050). Ctgf siRNA treatment reduced the collagen content significantly to 47.6% (P = 0.028) of that in bleomycin-induced skin, and SPARC siRNA treatment reduced the collagen content to 64.6% (P = 0.077) but not very significantly (Figure 3-2). The difference of collagen reduction (P = 0.076) between SPARC siRNA treatment and Ctgf siRNA treatment was not very significant might due to the small sample size.

The siRNA treatments also showed a reduction of collagen in the lung tissues of bleomycin-induced mice (Figure 4-2). In bleomycin-induced mice, collagen content of lung tissues was 3.6-fold higher than that in saline-injected control mice (P = 0.014). In SPARC siRNA treated mice that also were bleomycin-induced, the collagen content of lung tissues was significantly reduced to 58% (P = 0.019) of that in bleomycin-induced mice without siRNA treatment. Ctgf siRNA also reduced the collagen content to a quite low level (68% of that without siRNA treatment) but without significance (P = 0.128). Further, no significant difference of collagen content was found between SPARC siRNA treatment and Ctgf siRNA treatment in bleomycin-injured lungs (P = 0.277).

siRNAs of SPARCand Ctgf attenuated over-expression of collagen and other fibrotic ECM genes induced by bleomycin in skin and lung tissues

Bleomycin injection induced an up-regulation of the Col1a2, Col3a1, Ctgf and SPARC gene in both skin (Figure 5A, P = 0.028, 0.016, 0.049 and 0.0005, respectively) and lung tissues (Figure 5B, P = 0.015, 0.005, 0.041 and 0.056, respectively) of the mice significantly or marginal significantly. However, in Ctgf siRNA or SPARC siRNA treated mice skin that also received bleomycin injection, the expression of the Col1a2 and Col3a1 appeared to be normal in skin tissues (Figure 5A, P = 0.025 and 0.003 for each gene in Ctgf siRNA treatment, and P = 0.031 and 0.010 in SPARC siRNA treatment), and were significantly improved in lung tissues (about 2.7-fold reduction for Col1a2 and 1.9-fold reduction for Col3a1, compared to bleomyin-injected mice without siRNA treatment, P < 0.05 for both) (Figure 5B). In addition to collagen gene expression, the Ctgf and the SPARC expression were significantly or marginal significantly reduced by SPARC siRNA and Ctgf siRNA treatment, respectively (Figure 5B). In detail, compared to bleomycin-induced skin and lungs, SPARC siRNA normalized Ctgf expression in both skin and lungs (2.6-fold reduction in both with P = 0.100 and 0.039, respectively). Similarly, Ctgf siRNA also reduced SPARC expression in skin and lungs (2.9-fold and 1.5-fold reduction with P = 0.044 and 0.102, respectively).

Discussion

Although fibrosis is usually an irreversible pathological condition, targeting underlying molecular effectors may reverse an active status of the fibrotic process, and subsequently inhibit fibrosis. The TGF-β signaling pathway is associated with active fibrosis [22, 23]. It begins with the binding of the TGF-β ligand to the TGF-β type II receptor, which catalyses the phosphorylation of the type I receptor on the cell membrane. The type I receptor then induces the phosphorylation of receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs) that bind the coSMAD. The phosphorylated R-SMAD/coSMAD complex enters the nucleus acting as transcription factors to regulate target gene expression [22, 23]. CTGF (connective tissue growth factor) is a down-stream gene that can be activated by the TGF-β signaling pathway [23, 24]. Activation of CTGF is associated with potent and persistent fibrotic changes in the tissues, which is typically represented as accumulation of the ECM components including collagens [24, 25]. SPARC also is involved in TGF-β signaling. It was reported that SPARC stimulated Smad2 phosphorylation and Smad2/3 nuclear translation in lung epithelial cells [27]. Recently, while examining SPARC regulatory role on the ECM components in human fibroblasts using linear structure equations, we demonstrated that SPARC positively controlled the expression of CTGF [26]. Although down-regulation of CTGF has been employed in treating fibrotic conditions [28], application of SPARC inhibition in attenuation of a fibrotic process in a therapeutic animal model has not been reported.

The studies described here first utilized the fibroblasts obtained from the TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice that were induced for constitutively active TGF-β receptor I. After transfection of SPARC siRNA, the fibroblasts showed a decreased expression of Col1a2 that was originally over-expressed in the TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice (Figure 2). This phenomenon suggests that SPARC inhibition may interrupt fibrotic TGF-β signaling, which generally induces collagen production. Although the specific mechanism for this suppression is unclear, multiple previous studies have demonstrated a mutual regulatory relationship between SPARC and TGF-β signaling [14, 26, 29]. This notion also is supported by the observation of an over-expression of SPARC in the fibroblasts of the TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice (Figure 1). It should be noted that the Ctgf expression in the fibroblasts was not reduced upon SPARC inhibition. These results appear to contradict our previous report of parallel inhibition of SPARC and CTGF expression in human fibroblasts by SPARC siRNA [14]. A possible explanation is that over-expressed Ctgf from constitutively activated TGF-β signaling in these fibroblasts may confer resistance to a down-regulatory effect from SPARC siRNA. However, such resistance appeared to have limited influence on any down-regulatory effect of SPARC siRNA on collagen type 1, which suggests that CTGF is not a sole contributor to TGF-β signaling-associated fibrosis.

Bleomycin induced fibrosis in mice usually occurs after inflammation in which TGF-β is up-regulated [30]. Our in vivo application of SPARC siRNA demonstrated that inhibition of SPARC significantly reduced fibrosis in skin and lungs induced by bleomycin. In the treatment of skin fibrosis, SPARC siRNAs reduced fiber bundles accumulated in the dermis with less mononuclear cell infiltrates (Figure 3-1). In addition to histological changes, the thickness of bleomycin-induced skin treated with SPARC siRNA showed over 50% reduction compared to that without SPARC siRNA treatment (data not shown). The changes of tissue fibrotic level further were confirmed with significantly decreased collagen gene expression (Figure 5A). Non-crosslinked fibrillar collagen in the skin tissues also showed an average of 35.4% reduction after SPARC siRNA treatment (Figure 3-2).

In the treatment of lungs, SPARC siRNA reduced the disruption and inflammatory cells of the alveoli induced by bleomycin (Figure 4-2), which was accompanied with attenuated gene expression and protein content of collagens as compared to that without siRNA treatment (Figures 5B and 4-3). In addition, a significant reduction of the Ccl2 expression in the siRNA-treated lung tissues also suggests an improvement of inflammation supporting the findings in histological staining. These observations are consistent with previous reports on SPARC-null mice that exhibited attenuation of inflammation and fibrosis in kidneys [31]. While precise mechanism of these changes is still unknown, increased expression of SPARC was reported to correlate with the levels of inflammatory markers [32, 33]. It is likely that SPARC inhibition altered composition of microenvironment of the tissues that may restrain inflammatory response. On the other hand, much higher levels of gene expression of Col1A2 and Col3A1, and protein content of collagen were observed in bleomycin-induced lung tissues when they were compared to that in skin tissues (5.2-fold, 6.7-fold and 3.6-fold increase vs. 3.8-fold, 2.8-fold and 2.2-fold increase, respectively), which suggested that tissue damage and fibrosis in lung might be more severe than that in skin. In this case, treatment of bleomycin-induced lung damage might present a bigger challenge than that of skin, and the siRNA treatment through intratracheal instillation may be in need of further optimization. These notions were supported by similar findings in the treatment with the Ctgf siRNA, a positive control for anti-fibrotic effects.

Nevertheless, SPARC inhibition showed a clear anti-fibrotic effect in bleomycin-induced skin and lung tissues. Notably, these changes were accompanied with a significant down regulation of Ctgf that paralleled with Ctgf up-regulation in bleomycin-induced tissues. Thus, SPARC might regulate the collagen expression through affecting the expression of Ctgf, a TGF-β activity biomarker and down-strain gene, in bleomycin-induced mice. These observations combined with the results of anti-fibrotic effects of SPARC siRNA in fibroblasts of the Tgfbr1 knock-in mouse further support a mutually regulatory relationship between SPARC and TGF-β signaling.

Conclusions

Studies described here consistently demonstrated that inhibition of SPARC with siRNA significantly reduced collagen expression in both in vitro transgenic Tgfbr1 fibroblast model and in vivo bleomycin-induced fibrotic mouse models. This is the first attempt to examine the anti-fibrotic effects of SPARC inhibition using siRNA with tissue-specific administration in skin and lungs in vivo. The results obtained from these studies provide favorable evidence that SPARC may be used as a bio-target for application of anti-fibrosis therapies.

Abbreviations

- Ccl2:

-

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2, also known as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1)

- Col:

-

collagen

- Ctgf:

-

connective growth factor

- ECM:

-

extracellular matrix

- HE:

-

hematoxylin and eosin

- siRNA:

-

small interfering RNA

- SPARC :

-

secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteine

- SSc:

-

systemic sclerosis

- TGF-β:

-

transforming growth factor beta

References

Abdelaziz MM, Samman YS, Wali SO, Hamad MM: Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: is there anything new?. Respirology. 2005, 10: 284-289. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00712.x.

Tome S, Lucey MR: Review article: Current management of alcoholic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004, 19: 707-714. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01881.x.

Henness S, Wigley FM: Current drug therapy for scleroderma and secondary Raynaud's phenomenon: evidence-based review. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007, 19: 611-618. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282f13137.

Kuhn C, Mason RJ: Immunolocalization of SPARC, tenascin, and thrombospondin in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 1995, 147: 1759-1769.

Pichler RH, Hugo C, Shankland SJ, Reed MJ, Bassuk JA, Andoh TF, Lombardi DM, Schwartz SM, Bennett WM, Alpers CE, Sage EH, Johnson RJ, Couser WG: SPARC is expressed in renal interstitial fibrosis and in renal vascular injury. Kidney Int. 1996, 50: 1978-1989. 10.1038/ki.1996.520.

Frizell E, Liu SL, Abraham A, Ozaki I, Eghbali M, Sage EH, Zern MA: Expression of SPARC in normal and fibrotic livers. Hepatology. 1995, 21: 847-854.

Raines EW, Lane TF, Iruela-Arispe ML, Ross R, Sage EH: The extracellular glycoprotein SPARC interacts with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-AB and -BB and inhibits the binding of PDGF to its receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992, 89: 1281-1285. 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1281.

Zhou X, Tan FK, Reveille JD, Wallis D, Milewicz DM, Ahn C, Wang A, Arnett FC: Association of novel polymorphisms with the expression of SPARC in normal fibroblasts and with susceptibility to scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 2990-2999. 10.1002/art.10601.

Vuorio T, Kähäri VM, Black C, Vuorio E: Expression of osteonectin, decorin, and transforming growth factor-beta 1 genes in fibroblasts cultured from patients with systemic sclerosis and morphea. J Rheumatol. 1991, 18: 247-251.

Macko RF, Gelber AC, Young BA, Lowitt MH, White B, Wigley FM, Goldblum SE: Increased circulating concentrations of the counteradhesive proteins SPARC and thrombospondin-1 in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Relationship to platelet and endothelial cell activation. J Rheumatol. 2002, 29: 2565-2570.

Davies CA, Jeziorska M, Freemont AJ, Herrick AL: Expression of osteonectin and matrix Gla protein in scleroderma patients with and without calcinosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006, 45: 1349-1355. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei277.

Brekken RA, Sage EH: SPARC, a matricellular protein: at the crossroads of cell-matrix. Matrix Biol. 2001, 19: 816-827. 10.1016/S0945-053X(00)00133-5.

Schiemann BJ, Neil JR, Schiemann WP: SPARC inhibits epithelial cell proliferation in part through stimulation of the transforming growth factor-beta-signaling system. Mol Biol Cell. 2003, 14: 3977-3988. 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0001.

Zhou X, Tan FK, Guo X, Wallis D, Milewicz DM, Xue S, Arnett FC: Small interfering RNA inhibition of SPARC attenuates the profibrotic effect of transforming growth factor β1 in cultured normal human fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 257-261. 10.1002/art.20785.

Strandjord TP, Madtes DK, Weiss DJ, Sage EH: Collagen accumulation is decreased in SPARC-null mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol. 1999, 277: L628-635.

Dykxhoorn DM, Novina CD, Sharp PA: Killing the messenger: short RNAs that silence gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003, 4: 457-467. 10.1038/nrm1129.

Duchaine TF, Slack FJ: RNA interference and micro RNA-oriented therapy in cancer: rationales, promises, and challenges. Curr Oncol. 2009, 16: 61-66. 10.3747/co.v16i4.486.

de Fougerolles A, Vornlocher HP, Maraganore J, Lieberman J: Interfering with disease: a progress report on siRNA-based therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007, 6: 443-453. 10.1038/nrd2310.

Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG: Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009, 8: 129-138. 10.1038/nrd2742.

Zhou XD, Tan FK, Guo X, Arnett FC: Attenuation of collagen synthesis with small interfering RNA of SPARC in cultured fibroblasts from the skin of patients with scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 2626-2631. 10.1002/art.21973.

Sonnylal S, Denton CP, Zheng B, Keene DR, He R, Adams HP, Vanpelt CS, Geng YJ, Deng JM, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B: Postnatal induction of transforming growth factor β signaling in fibroblasts of mice recapitulates clinical, histologic, and biochemical features of scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 334-344. 10.1002/art.22328.

Border WA, Noble NA: Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994, 331: 1286-1292. 10.1056/NEJM199411103311907.

Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF: Role of transforming growth factor beta in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342: 1350-1358. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807.

Grotendorst GR: Connective tissue growth factor: a mediator of TGF-β action on fibroblasts. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997, 8: 171-179. 10.1016/S1359-6101(97)00010-5.

Chujo S, Shirasaki F, Kawara S, Inagaki Y, Kinbara T, Inaoki M, Takigawa M, Takehara K: Connective tissue growth factor causes persistent proalpha2(I) collagen gene expression induced by transforming growth factor-β in a mouse fibrosis model. J Cell Physiol. 2005, 203: 447-456. 10.1002/jcp.20251.

Zhou XD, Xiong MM, Tan FK, Guo XJ, Arnett FC: SPARC. An upstream regulator of connective tissue growth factor in response to transforming growth factor β stimulation. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 3885-3889. 10.1002/art.22249.

Schiemann BJ, Neil JR, Schiemann WP: SPARC inhibits epithelial cell proliferation in part through stimulation of the transforming growth factor-β-signaling system. Mol Biol Cell. 2003, 14: 3977-3988. 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0001.

George J, Tsutsumi M: siRNA-mediated knockdown of connective tissue growth factor prevents N-nitrosodimethylamine-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. Gene Ther. 2007, 14: 790-803. 10.1038/sj.gt.3302929.

Francki A, McClure TD, Brekken RA, Motamed K, Murri C, Wang T, Sage EH: SPARC regulates TGF-beta1-dependent signaling in primary glomerular mesangial cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004, 91: 915-925. 10.1002/jcb.20008.

Cutroneo KR, White SL, Phan SH, Ehrlich HP: Therapies for bleomycin induced lung fibrosis through regulation of TGF-beta1 induced collagen gene expression. J Cell Physiol. 2007, 211: 585-589. 10.1002/jcp.20972.

Socha MJ, Manhiani M, Said N, Imig JD, Motamed K: Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine deficiency ameliorates renal inflammation and fibrosis in angiotensin hypertension. Am J Pathol. 2007, 171: 1104-1112. 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061273.

Kos K, Wong S, Tan B, Gummesson A, Jernas M, Franck N, Kerrigan D, Nystrom FH, Carlsson LM, Randeva HS, Pinkney JH, Wilding JP: Regulation of the fibrosis and angiogenesis promoter SPARC/osteonectin in human adipose tissue by weight change, leptin, insulin, and glucose. Diabetes. 2009, 58: 1780-1788. 10.2337/db09-0211.

Reding T, Wagner U, Silva AB, Sun LK, Bain M, Kim SY, Bimmler D, Graf R: Inflammation-dependent expression of SPARC during development of chronic pancreatitis in WBN/Kob rats and a microarray gene expression analysis. Physiol Genomics. 2009, 38: 196-204. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00028.2009.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Department of the Army, Medical Research Acquisition Activity, grant number PR064803 to Zhou, the National Institutes of Health, grant number P50 AR054144 to Arnett and the National Science Foundation of China, grant number 30971574 to Wang.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors are preparing a patent application for SPARC inhibition in the treatment of fibrosis. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Authors' contributions

WJ carried out the animal studies and most of the molecular studies. LS carried out tissue histological examination. GX and ZX carried out molecular studies. CB and SS provided fibroblasts from TBR1CA; Cre-ER mice. FA participated in coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. ZX carried out animal studies and participated in study design and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, JC., Lai, S., Guo, X. et al. Attenuation of fibrosis in vitro and in vivo with SPARC siRNA. Arthritis Res Ther 12, R60 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2973

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2973