Abstract

Background

Zolpidem is a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic widely used to manage insomnia. Zolpidem-triggered atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with cardiomyopathy has never been reported before.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy-related cardiomyopathy attempted suicide and developed new-onset AF after zolpidem overdose. One year before admission, the patient visited our clinic due to chest discomfort and fatigue after daily walks for 1 month; both electrocardiography (ECG) and 24-hour Holter ECG results did not detect AF. After administration of cardiac medication (digoxin 0.125 mg/day, spironolactone 40 mg/day, furosemide 20 mg/day, bisoprolol 5 mg/day, sacubitril/valsartan 12/13 mg/day), he felt better. AF had never been observed before this admission via continuous monitoring during follow-up. Sixteen days before admission, the patient saw a sleep specialist and started zolpidem tartrate tablets (10 mg/day) due to insomnia for 6 months; ECG results revealed no significant change. The night before admission, the patient attempted suicide by overdosing on 40 mg of zolpidem after an argument, which resulted in severe lethargy. Upon admission, his ECG revealed new-onset AF, necessitating immediate cessation of zolpidem. Nine hours into admission, AF spontaneously terminated into normal sinus rhythm. Results from the ECG on the following days and the 24-hour Holter ECG at 1-month follow-up showed that AF was not detected.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable clinical evidence indicating that zolpidem overdose may induce AF in patients with cardiomyopathy. It serves as a critical warning for clinicians when prescribing zolpidem, particularly for patients with existing heart conditions. Further large-scale studies are needed to validate this finding and to explore the mechanisms between zolpidem and AF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Zolpidem, a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic, is widely used in the pharmacological therapy of insomnia in adults [1]. It has adverse events, including falls and subsequent fractures [2, 3], neuropsychological adverse effects such as parasomnias, amnesia, hallucinations, and suicidality [4, 5], as well as abuse, dependence, and withdrawal [6].

Arrhythmia is also a side effect of zolpidem, although rarely reported. There have been instances of zolpidem causing QT prolongation and provoking ventricular fibrillation [7, 8]. However, atrial fibrillation (AF) as a side effect of zolpidem use remains unreported. Herein, we present a case of a 40-year-old man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD)-related cardiomyopathy who attempted suicide and developed new-onset AF after zolpidem overdose.

Case presentation

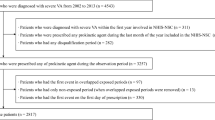

A 40-year-old man who attempted suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills (zolpidem tartrate tablets, 40 mg) resulting in lethargy for 8 h was admitted to our hospital. Upon presentation, his vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 91/66 mmHg; irregular heart rate, 54 beats/min; and normal oxygen saturation. The timeline of the case is shown in Table 1.

The patient has suffered from mild skeletal muscle weakness since the age of 15 years and was diagnosed with DMD through dystrophy gene analysis and clinical manifestations. In the patient’s family, four men spanning three generations were also diagnosed with DMD. Additional image files show this in more detail [see Additional file 1]. Multiplex PCR analysis of the dystrophin gene from peripheral blood revealed a deletion of exons 45–49, which applies to all family members (except the patient’s uncle [I 1] for death). Additional image files show this in more detail [see Additional file 2]. There is no involvement of family in this study. There was no other special discovery in the patient’s past history, personal history and family history in addition to the above.

The patient visited our clinic due to chest discomfort and fatigue after daily walks for 1 month since the previous year. His electrocardiography (ECG) (Figs. 1) and 24-hour Holter ECG results revealed a complete right bundle branch block and premature ventricular contractions. Moreover, his ECG results revealed diffuse severe hypokinesis with an estimated ejection fraction of 22.7%, enlarged left atrium (58.0 mm) and left ventricle (72.7 mm), as well as mild mitral regurgitation. The patient regularly took oral medication including digoxin (0.125 mg/day), spironolactone (40 mg/day), furosemide (20 mg/day), bisoprolol (5 mg/day), sacubitril/valsartan (12/13 mg/day). His symptoms improved after taking these medications. AF had never been observed before this admission via continuous monitoring during follow-up.

Sixteen days before this hospital admission, the patient visited a sleep clinic and started zolpidem tartrate tablets (10 mg/day) due to insomnia for 6 months. His ECG results revealed no significant change.

The night before admission, the patient attempted suicide by taking 40 mg zolpidem tartrate tablets after an argument, resulting in severe lethargy. At admission, his ECG revealed new-onset AF with a heart rate of 54 beats/min (Fig. 2) and diffuse severe hypokinesis with an estimated ejection fraction of 35%, enlargement of the left atrium (60.2 mm) and left ventricle (73.0 mm), as well as mild mitral regurgitation, roughly the same as before. Notable laboratory test values showed no significant dynamic change before and after admission: an elevated creatine kinase, 1059 U/L; creatine kinase-MB, 41.7 U/L; troponin-I, 0.82 ng/ml; and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide, 911.66 ng/L. Zolpidem was stopped immediately, heart rhythm was monitored by telemetry, and i.v. fluids were administered upon admission. The patient stabilized 9 h after admission, and AF spontaneously terminated into normal sinus rhythm. The medication history was carefully confirmed by the patient and his family. His body mass index (BMI) was 23.9 kg/m2. Cognitive behavioral therapy was performed to improve his insomnia, and he was discharged 3 days after admission. According to the ECG monitor during the next few days and the 24-hour Holter ECG at 1-month follow-up, his heart rate maintained a sinus rhythm, and no AF was detected.

Causality, severity, and preventability assessment of the adverse drug reaction (ADR) are shown in Table 2. According to the Naranjo causality scale and World Health Organization Uppsala Monitoring Center (WHO-UMC) assessment scale, this ADR and zolpidem may be associated. The Hartwig’s severity scale score indicated a moderate severity level for the reaction (level 4b). The ADR may indeed have been preventable based on the modified Schoumock and Thornton scale [9].

All appropriate patient consent forms for images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal were obtained for this case report. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Discussion and conclusions

Patients with DMD experience evolving insomnia throughout their lifetimes [10]. It is common to identify DMD patients experiencing chronic insomnia who also suffer from other psychiatric comorbidities such as mood and anxiety disorders [11]. Certain medications can be used to augment nonpharmacologic interventions to manage insomnia. Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, including zolpidem, are commonly prescribed by physicians [12]. Clinically, zolpidem is widely used in patients with insomnia, including DMD patients. However, DMD patients have a high risk of suicide due to the possible coexistence of other psychiatric disorders, as in our patient. Nonpharmacologic treatment strategies are preferred for this condition.

Zolpidem is associated with arrhythmia. Two instances have indicated that zolpidem could contribute to a prolonged QTc and ventricular fibrillation. However, AF after zolpidem use has not been reported before.

Over the past hundred years, AF is the arrhythmia that has been studied the most among all other heart rhythm disorders [13]. However, crucial questions regarding the formation and perpetuation of the disease remain unanswered. To the best of our knowledge, atrial fibrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, aging, arterial hypertension, obesity, excessive alcohol use, diabetes mellitus, certain medications, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and genetic factors contribute to the development of AF [14]. Other causes such as electrolyte disorders, intracranial pressure elevation, hyperthyroidism, infection, and hyperthermia have been ruled out in the present case. Results of the causality analysis of the new-onset AF are shown in Table 3.

In this case, the underlying disease (DMD-related cardiomyopathy) and combined medication may increase the risk of AF.

In the current scenario, cardiomyopathy was considered stable based on the consistent clinical manifestations and ECG and laboratory test results at admission. New-onset heart failure or any other types of arrhythmia had not been observed. AF had not been detected before. After stopping zolpidem, AF subsequently terminated spontaneously into normal sinus rhythm and did not recur. Therefore, the association between cardiomyopathy and new-onset AF remains unclear.

The patient attempted suicide after a family argument, indicating that psychological stress might have contributed to the occurrence of atrial fibrillation. However, the conclusion about the correlation between psychological factors and AF remains controversial [15, 16]. The current European Society of Cardiology guideline on AF mentions psychological distress and emotional fluctuations as known consequences of AF only but not as risk factors [17].

The patient has been taking normal doses of digoxin, spironolactone, furosemide, bisoprolol, and sacubitril/valsartan since the previous year before admission. The combined effect of these drugs on heart rhythm could be complex. Digoxin, spironolactone, furosemide, bisoprolol, and sacubitril/valsartan are commonly considered therapeutic drugs for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, but not as risk factors for inducing AF [18]. Zolpidem has few drug interactions. The patient was taking multiple cardiac medications, and so far, no interactions between these drugs and zolpidem have been observed [19]. Existing evidence suggests that the coadministration of digoxin does not alter the pharmacokinetics of zolpidem [20]. Zolpidem was primarily suspected due to its overdose proximate to the new-onset AF; once withdrawn, the patient’s AF resolved. Therefore, the overdose on zolpidem corresponds as the most probable cause of AF based on the Naranjo causality scale and WHO-UMC assessment scale.

Zolpidem could have caused AF via respiratory depression. DMD and insomnia are both commonly comorbid with OSA [21, 22]. We are not sure if the patient has OSA, but certainly the high dose of zolpidem could have caused it because of pharyngeal muscle relaxation and delayed arousal worsening hypoxaemia [23]. Obstructed inspiration generates large negative intrathoracic pressure fluctuations, leads to acute atrial distension, shortens atrial refractoriness, slows conduction, and increases the occurrence of intraatrial conduction block in humans. These acute transient arrhythmogenic changes during apnea may contribute to the development of AF [24]. In addition, zolpidem can decrease central respiratory drive, increase upper airway resistance, decrease inspiratory flow, decrease carbon dioxide ventilatory response, and increase blood carbon dioxide concentration [25]. Hypercapnia increases effective refractory period in action potentials and conduction in the atria which can increase vulnerability to AF in pre-existing atrial myopathy [26], which was very likely present in this case with atrial dilation.

Several observational epidemiological studies have produced conflicting results on the relationship between hypnotic usage and heart disease. A meta-analysis of observational epidemiological studies supported that zolpidem showed a decreased risk (− 29%) of developing or dying from heart disease, but benzodiazepines were associated with an increased risk (80%) of or mortality from heart disease [27]. Exposure to benzodiazepines was associated with increased cardiovascular mortality (HR: 1.65; 95% CI 1.39, 1.97) in a large population study with 85,353 women, but not when further adjusted for antidepressant use (HR: 1.15; 95% CI 0.94, 1.40), nor in the multivariable model (HR: 0.93; 95% CI 0.75, 1.16) [28]. Therefore, it is still unknown whether zolpidem could increase the risk of AF.

In this case, it is of interest that only 40 mg zolpidem induced severe lethargy and new-onset AF, and this dose is generally not considered toxic. On the contrary, a study on the subjective effects of zolpidem showed that 20 mg was considered “pleasant” and gave a “high” despite zolpidem increased ratings of “sleepy” [29]. When given in a nightly dosage of up to 20 mg, zolpidem is generally well tolerated by patients with insomnia, only 5.2% of them resulted in lethargy [30]. Once the patient stabilized after admission, the patient and his family denied intake of other toxic substances. Because zolpidem is metabolized through cytochrome P450, while bisoprolol [31], digoxin [32], spironolactone [33], and furosemide [34] have the same metabolic pathway through cytochrome P450, co-application of these medications may result in impaired metabolism of affected compounds and elevate zolpidem plasma concentrations toward critical levels. The presence of cardiomyopathy that reduce the repolarization reserve is expected to precipitate AF during zolpidem treatment.

Another thing worth mentioning is that the new-onset AF was accompanied by a slow ventricular rate. This patient had right bundle branch block and probably conductive system disorder (not uncommon in patients with DMD), which we believe was the main reason for the slow heart rate during AF. Moreover, a rat study supported the fluctuation of heart rate would be attenuated with a higher dose of zolpidem [35]. As in this case, the slow ventricular rate of AF may also associated with the zolpidem overdose.

The main limitation of this case report is the lack of toxicity analyses and recurrence of ADR with rechallenge, which would not be ethical. Patients with any form of cardiomyopathy have a high risk of AF. We cannot completely rule out accidental detection of AF during admission in this case.

This case suggests that zolpidem overdose could increase the risk of AF in patients with cardiomyopathy, as indicated by both causality analysis and explainable mechanism. It serves as a critical warning for clinicians when prescribing zolpidem, particularly for patients with existing heart conditions. Further large-scale studies are needed to validate this finding and to explore the mechanisms between zolpidem and AF.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request with the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- DMD:

-

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- ADR:

-

Adverse drug reaction

- WHO-UMC:

-

World Health Organization Uppsala Monitoring Center

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

References

Edinoff AN, Wu N, Ghaffar YT, Prejean R, et al. Zolpidem: Efficacy and Side effects for Insomnia. Health Psychol Res. 2021;9(1):24927. https://doi.org/10.52965/001c.24927.

Treves N, Perlman A, Kolenberg Geron L, Asaly A, et al. Z-drugs and risk for falls and fractures in older adults-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):201–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx167.

Westermeyer J, Carr TM. Zolpidem-Associated consequences: an updated literature review with Case Reports. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(1):28–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001074.

Stallman HM, Kohler M, White J. Medication induced sleepwalking: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;37:105–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.01.005.

Schifano F, Chiappini S, Corkery JM, Guirguis A. An insight into Z-Drug abuse and dependence: an examination of reports to the European Medicines Agency Database of suspected adverse drug reactions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;22(4):270–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyz007.

Chiaro G, Castelnovo A, Bianco G, Maffei P, et al. Severe chronic abuse of Zolpidem in Refractory Insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(7):1257–9. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.7240.

Suarez L, Kolla BP, Hall-Flavin D, Mansukhani MP. QTc prolongation secondary to Zolpidem Use. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22(2):19l02506. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.19l02506.

Ahn HJ, Jeong WJ, Kim KJ, Kim SC, et al. Serial plasma and urine measurements of a patient with acute intoxication of zolpidem and flunitrazepam resulting in QT prolongation and ventricular tachycardia. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(6):501–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1663206.

Jiang H, Lin Y, Ren W, Fang Z, et al. Adverse drug reactions and correlations with drug-drug interactions: a retrospective study of reports from 2011 to 2020. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:923939. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.923939.

MacKintosh EW, Chen ML, Benditt JO. Lifetime care of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(4):485–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.08.011.

Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, Mercuri E, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00248-3.

Hu X, Jong GP, Wang L, Lin MC, et al. Hypnotics Use is Associated with elevated Incident Atrial Fibrillation: a propensity-score matched analysis of Cohort Study. J Pers Med. 2022;12(10):1645. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12101645.

Lau DH, Linz D, Sanders P. New findings in Atrial Fibrillation mechanisms. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2019;11(4):563–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccep.2019.08.007.

Sagris M, Vardas EP, Theofilis P, Antonopoulos AS, et al. Atrial fibrillation: Pathogenesis, predisposing factors, and Genetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010006.

Fu Y, He W, Ma J, Wei B. Relationship between psychological factors and atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Med (Baltim). 2020;99(16):e19615. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000019615.

Wu H, Li C, Li B, Zheng T, et al. Psychological factors and risk of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2022;362:85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.05.048.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the management of Heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136(6):e137–61. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509.

Dang A, Garg A, Rataboli PV. Role of zolpidem in the management of insomnia. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(5):387–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00158.x.

Salvà P, Costa J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem. Therapeutic implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29(3):142–53. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199529030-00002.

Ong JC, Crawford MR. Insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Clin. 2013;8(3):389–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2013.04.004.

LoMauro A, D’Angelo MG, Aliverti A. Sleep disordered breathing in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(5):44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0750-1.

Carberry JC, Fisher LP, Grunstein RR, Gandevia SC, et al. Role of common hypnotics on the phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnoea: paradoxical effects of zolpidem. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(6):1701344. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01344-2017.

Linz D, McEvoy RD, Cowie MR, Somers VK, et al. Associations of Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Atrial Fibrillation and continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(6):532–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0095.

Stege G, Vos PJ, van den Elshout FJ, Richard Dekhuijzen PN, et al. Sleep, hypnotics and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2008;102(6):801–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.12.026.

Stevenson IH, Roberts-Thomson KC, Kistler PM, et al. Atrial electrophysiology is altered by acute hypercapnia but not hypoxemia: implications for promotion of atrial fibrillation in pulmonary disease and sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(9):1263–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.03.020.

Kim YH, Kim HB, Kim DH, Kim JY, et al. Use of hypnotics and the risk of or mortality from heart disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33(4):727–36. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.282.

Mesrine S, Gusto G, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Use of benzodiazepines and cardiovascular mortality in a cohort of women aged over 50 years. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(11):1475–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-2515-4.

Licata SC, Mashhoon Y, Maclean RR, Lukas SE. Modest abuse-related subjective effects of zolpidem in drug-naive volunteers. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22(2):160–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0b013e328343d78a.

Langtry HD, Benfield P, Zolpidem. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential. Drugs. 1990;40(2):291–313. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199040020-00008.

Horikiri Y, Suzuki T, Mizobe M. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of bisoprolol enantiomers in humans. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87(3):289–94. https://doi.org/10.1021/js970316d.

Salphati L, Benet LZ. Metabolism of digoxin and digoxigenin digitoxosides in rat liver microsomes: involvement of cytochrome P4503A. Xenobiotica. 1999;29(2):171–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/004982599238722.

Garcia PJ, Mundaca H, Ugarte-Gil C, Leon P, et al. Randomized clinical trial to compare the efficacy of ivermectin versus placebo to negativize nasopharyngeal PCR in patients with early COVID-19 in Peru (SAINT-Peru): a structured summary of a study protocol for randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05236-2.

Yang KH, Choi YH, Lee U, Lee JH, et al. Effects of cytochrome P450 inducers and inhibitors on the pharmacokinetics of intravenous furosemide in rats: involvement of CYP2C11, 2E1, 3A1 and 3A2 in furosemide metabolism. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61(1):47–54. https://doi.org/10.1211/jpp/61.01.0007.

Mailliet F, Galloux P, Poisson D. Comparative effects of melatonin, zolpidem and diazepam on sleep, body temperature, blood pressure and heart rate measured by radiotelemetry in Wistar rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156(4):417–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002130100769.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nature Research Editing Service (https://authorservices.springernature.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was funded by the Foundation of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department (Grant No. Y202146832 and Y202249328), Science and Technology program of Jinhua Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 2020-4-104), Science and Technology program of Yiwu Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 2020-3-059), Foundation of The Fourth Affiliated Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Grant No. JG20230203). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish or the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LXL wrote the report, performed the research and took the pictures. JYP wrote a part of the report and revised the report and is the corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the publication of this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of The Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Jin, Y. Zolpidem-triggered atrial fibrillation in a patient with cardiomyopathy: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 24, 339 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-04016-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-04016-5