Abstract

Background

An association has been observed between primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and systemic rheumatic diseases (SRDs) in observational studies, however the exact causal link remains unclear. We aimed to evaluate the causal effects of PBC on SRDs through Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Methods

The genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary data were obtained from MRC IEU OpenGWAS and FinnGen databases. Independent genetic variants for PBC were selected as instrumental variables. Inverse variance weighted was used as the main approach to evaluate the causal effects of PBC on Sjögren syndrome (SS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), systemic sclerosis (SSc), mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) and polymyositis (PM). Horizontal pleiotropy and heterogeneity were measured by MR‒Egger intercept test and Cochran’s Q value, respectively.

Results

PBC had causal effects on SS (OR = 1.177, P = 8.02e-09), RA (OR = 1.071, P = 9.80e-04), SLE (OR = 1.447, P = 1.04e-09), SSc (OR = 1.399, P = 2.52e-04), MCTD (OR = 1.306, P = 4.92e-14), and PM (OR = 1.416, P = 1.16e-04). Based on the MR‒Egger intercept tests, horizontal pleiotropy was absent (all P values > 0.05). The robustness of our results was further enhanced by the leave-one-out method.

Conclusions

Our research has provided new insights into PBC and SRDs, indicating casual effects on various SRDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is an autoimmune hepatobiliary disease characterized by destroyed interlobular bile ducts, leading to liver cirrhosis and an increased need for liver transplantation [1]. PBC is predominantly found in females, and its prevalence is increasing [2]. The estimated worldwide incidence and prevalence of PBC are 1.76 and 14.6 cases per 100 000 individuals, respectively [3]. Currently, there are limited treatments available for PBC and UDCA remains the primary first-line therapy, which may moderate disease progression and prolong transplant-free survival in PBC patients. Although extensive studies have been conducted on the immunological processes that cause liver injury [4, 5], the mechanism of PBC is still poorly understood. Therefore, it is essential to clarify the fundamental pathological mechanisms to develop more practical therapeutic strategies for PBC, as well as for extrahepatic complications.

Patients with PBC usually have various extrahepatic manifestations, particularly systemic rheumatic diseases (SRDs) [6, 7]. SRDs are chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disorders with the presence of autoantibodies which may damage various systems. In a recent retrospective cohort of 1554 PBC individuals, the prevalence of SRDs was 17% [8]. Furthermore, patients with PBC frequently have autoantibodies associated with SRDs [9]. To date, coexisting PBC and SRDs have been reported in many observational studies [6,7,8,9,10], and the association between PBC and SRDs has received considerable scientific attention. The co-occurrence of PBC and SRDs suggests the possibility of common pathogenic mechanisms [9, 10]. However, the causal associations between PBC and SRDs are still unclear and further efforts are urgently needed to assess the causality between these disorders and develop prevention strategies.

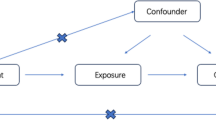

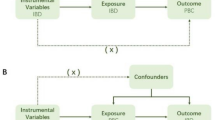

It is challenging to draw valid conclusions about the causal associations between PBC and SRDs in traditional observational studies due to unadjusted confounders variables and reverse causality. Using genetic variation as instrumental variables (IVs) in Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis has been proven to be an effective technique in epidemiologic research for evaluating the exposure’s causal effects on outcomes [11]. At the time of gametogenesis, the genetic variations are assigned in a random manner, potentially reducing the impact of confounding factors. MR is particularly significant in epidemiological research, as it strengthens the ability to establish causality by minimizing confounder effects, providing more robust and reliable insights into the relationships between diseases. This investigation aimed to explore the causal link between PBC and SRDs through two-sample MR analysis, indicating positive causal effects of PBC on SRDs.

Materials and methods

Data sources

To eliminate genetic bias arising due to ethnic differences, the MR analysis was performed only in the European population. The genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary data for PBC [12] were obtained from the MRC IEU OpenGWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). All PBC cases fulfilled the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease criteria for PBC. The GWAS summary data for SRDs (Sjögren syndrome [SS], rheumatoid arthritis [RA], systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], systemic sclerosis [SSc], mixed connective tissue disease [MCTD] and polymyositis [PM]) were collected from the FinnGen consortium (R9 version) [13]. SRDs were classified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. The detailed information of GWAS data was shown in Table 1.

Study design

The MR selected single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as IVs to assess the causal associations between PBC and SRDs. Our study fulfilled the following three main hypotheses: (1) IVs had a strong correlation with exposure; (2) IVs had no associations with any confounders; and (3) IVs could only affect outcomes by associating with exposure, not directly affecting outcomes. Therefore, the included SNPs were of genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10e-8) without linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.001). The F-statistic was calculated according to a previously published MR study [14]. To avoid the bias of weak IVs, SNPs with an F-statistic below 10 were eliminated. We also excluded SNPs with palindromic alleles to avoid strand ambiguity and potential misinterpretation of the results. PhenoScanner database was used to screen and exclude SNPs that are related to confounders and outcomes.

Statistical analysis

To investigate causal effects, the inverse variance weighted (IVW) approach was performed as the main analysis using the TwoSampleMR package in R software (version 4.3.1). IVW combined the Wald estimates of causality for each IV to obtain overall estimates of the effect of exposure on outcome. Two complementary approaches (MR‒Egger and weighted median [WME]) were used to validate the IVW results. The MR‒Egger regression method carried out a weighted linear regression to produce a consistent estimate of the causal effect, independent of the validity of the SNPs. WME can provide reliable estimates when more than 50% of the weight is derived from valid SNPs. Outliers were identified by the MR-PRESSO package based on the p value of the outlier test, and subsequent causal estimates were calculated after outlier removal.

To ensure that the SNPs were consistent with the basic assumptions of the MR analysis, the MR‒Egger intercept test was used to assess the possible pleiotropic effects of the SNPs. Cochran’s Q value was used to quantify heterogeneity, and the presence of heterogeneity was determined if the P value was < 0.05. The IVW fixed effects method was used if the P value of the Cochran’s Q test was < 0.05, otherwise the random effects model was used. In addition, the robustness of the MR results was validated using the leave-one-out approach.

Results

After a series of strict quality control procedures, included SNPs for assessing the causal effects of PBC on SRDs were provided in the Supplemental Tables. The F-statistic values of included SNPs were more than 10, indicating that the IVs have sufficient power.

The causal relationships between PBC and SRDs were summarized in Table 2; Fig. 1. The IVW analysis showed that genetically predicted PBC had causal effects on RA (OR = 1.071, P = 9.80e-04), SS (OR = 1.177, P = 8.02e-09), SLE (OR = 1.447, P = 1.04e-09), SSc (OR = 1.399, P = 2.52e-04), MCTD (OR = 1.306, P = 4.92e-14) and PM (OR = 1.416, P = 1.16e-04). Consistent results were obtained by the WME method, showing that PBC was positively associated with RA (OR = 1.085, P = 2.88e-03), SS (OR = 1.160, P = 3.19e-04), SLE (OR = 1.464, P = 3.06e-07), SSc (OR = 1.519, P = 1.34e-03) and MTCD (OR = 1.371, P = 1.15e-12). MR‒Egger also verified the causal effects of PBC on SLE (OR = 1.672, P = 1.52e-02), SSc (OR = 2.072, P = 1.31e-02) and MTCD (OR = 1.540, P = 3.51e-04), and showed the same direction of causal effects on RA (OR = 1.059, P = 0.431), SS (OR = 1.163, P = 0.117) and PM (OR = 1.048, P = 0.860).

The included SNPs did not show any heterogeneity (Table 2). According to the MR‒Egger intercept tests, there was no horizontal pleiotropy in the present MR study (Table 2). Furthermore, the robustness of the MR analysis results was confirmed by the “leave-one-out” method (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Our research focused on the causal effect of PBC on SRDs, an issue previously unresolved in observational epidemiological studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first MR study to systemically assess the causal links between PBC and various SRDs. Although the potential mechanisms underlying PBC and SRDs were not fully understood, our study provided compelling evidence for the causal relationship between them. Heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy were absent in the present MR study. The reliability of our MR findings was demonstrated by sensitivity analysis. Our results indicate potential overlap in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these autoimmune diseases.

A close association has been observed between PBC and SRDs in previous observational studies. The prevalence of SRDs in PBC varied greatly in different cohorts. The reported prevalences of SS, RA, SLE, SSc, MCTD and PM in PBC are 3.5–73%, 1.8–13%, 1.3–3.7%, 1.4–12.3%, 0.6–3.1%, and 0.6% [6, 7], respectively. Serum autoantibodies associated with SRDs are often detected in PBC [9, 15], including rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP, anti-dsDNA, anti-Ro/SSA, etc. Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) exhibiting the “multiple nuclear dots” or “rim-like immunofluorescence” patterns showed high specificity for PBC and these ANAs were also detected in SRDs [16]. Though the previous studies have reported the co-existence of PBC and SRDs, our study provides stronger evidence for a causal relationship. Our study employed MR approach to evaluate the causal associations between PBC and SRDs, showing positive causal effects of PBC on SRDs.

The liver, as a major lymphoid organ, plays a crucial role in immune surveillance and regulation through its abundant lymphocytes and Kupffer cells, which may explain the observed associations between PBC and SRDs. The development of extrahepatic autoimmune disorders involves the interactions of both natural and adaptive immune responses that target cholangiocytes and various extrahepatic tissues [17]. It has been demonstrated that the L-12/IL-23-mediated Th1/Th17 signaling pathway plays important role in the development of PBC. A shift in the balance of Th1 to Th17 cells has been observed and is thought to contribute to the unfavorable disease progress [18]. Th1 and Th17 cells in adaptive immune responses also play crucial roles in SRDs [19,20,21]. For example, elevated serum levels of Th1 related cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL12 and IL18, are detected in SLE patients, and high levels of cytokines were positively associated with disease severity [22]. Th17 cells in SLE and SS are associated with increased production of IL-17, which promotes inflammation and autoantibody production [23, 24], further driving the autoimmune process. Besides, smoking is considered as a common risk factor for PBC and SRDs [25,26,27,28]. Smoking has been demonstrated to impair immune function through various mechanisms, including the induction of the inflammatory response, immune suppression, alteration of cytokine balances, which contribute to the development of various autoimmune diseases [29, 30]. Given the findings in the present MR analysis, it is imperative to implement effective screening strategies for the early detection of SRDs in PBC patients, particularly in those with a smoking habit.

There is growing evidence to suggest that there is a strong link between gut dysbiosis and autoimmunity [31, 32]. Perturbations in the gut microbiota could lead to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and an increase in Th17 cells, even in extraintestinal tissues. Patients with autoimmune diseases have different gut microbiota compositions compared to healthy subjects [33, 34]. Decreased bacterial diversity was observed in PBC cases and gut dysbiosis is associated with clinical prognosis [35, 36]. Alterations in the microbiota composition, such as Faecalibacterium and Lactobacillus, were found in PBC, RA, SLE, SS and SSc [32,33,34]. In addition, changes in the gut microbiota are correlated with the severity of SRDs and are being developed as a novel diagnostic method for several SRDs. To date, no research has yet been done on the microbiome of MCTD and polymyositis. Animal and clinical studies have shown promising results for gut microbiota-based therapy, supporting the hypothesis that changes in gut microbiota can affect autoimmune responses and disease outcomes [37]. However, the gut microbiota composition is frequently impacted by dietary and ecological factors, and further research with better matching controls is needed. In addition, potential mechanisms of microbiota urgently need to be urgently verified to explore the interaction between PBC and SRDs.

Considerable efforts have been made to investigate the genetic inheritance of PBC and SRDs [38, 39], highlighting the vital importance of genetic background between these diseases. Previous GWAS showed that PBC and SRDs shared some common genes involved in the IL12-mediated signaling pathway, including STAT4 and IRF5 [38, 39]. STAT4 and IRF5 are key transcription factors activated by IL-12 signaling, which promotes Th1 differentiation and IFN-γ production [40, 41]. These molecules are crucial in driving the inflammatory response and are implicated in the pathogenesis of both PBC and SRDs. These findings may provide an explanation for why individuals with common genes are more susceptible to concurrent SRDs in PBC. Osteopontin (OPN) is a versatile cytokine and adhesion molecule, acting as a unique regulator of both innate and adaptive immune responses [42]. OPN has a vital role in recruiting mononuclear cells to epithelioid granulomas and participating in bile duct injury through B-cell differentiation and plasma cell expansion in PBC [43]. OPN expression is upregulated in SS, RA, SLE and SSc, and OPN overexpression has been shown to be correlated with disease severity [42, 44,45,46]. For example, OPN overexpression has been associated with a predisposition to SLE and poor prognosis since OPN promotes the T follicular helper cells and enhances anti-nuclear antibody production [44]. Further comprehension of the genetic heredity of these disorders will be beneficial for clinical pharmacotherapy.

Although large samples of GWAS summary data were used for MR analysis, several limitations of this research should be recognized. First, the MR results in the present study were obtained from the European population. The causal association between PBC and SRDs remains inconclusive in other ethnic groups. Second, both PBC and SRDs are female-predominant. Due to the currently limited GWAS data, stratification of the genetic causal effects between PBC and SRDs by gender could not be explored. Third, only six SRDs were analyzed in this study. While our study focused on six SRDs, the possibility of causal relationships between PBC and other SRDs could not be excluded. Additionally, due to the lack of effective IVs for most SRDs in reverse MR analyses, causal effects of SRDs on PBC were not assessed. Finally, MR analysis only provides the causal association between PBC and SRDs, without explaining the biological process behind the connection. Hence, further experimental efforts are needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusions

The MR results show positive causal effects of PBC on SRDs, which holds significant clinical guidance for clinicians in daily medical practice. It may be advisable to regularly screen SRDs for patients with PBC, which may facilitate earlier diagnosis and timely management. Additionally, elucidating the shared genetic and biological mechanisms between these conditions can pave the way for novel therapeutic targets and personalized treatment approaches. In the future, multidisciplinary cooperation is essential for the satisfactory management of these patients.

Data availability

All GWAS data are publicly available in the MRC IEU OpenGWAS database (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) and FinnGen database (http://www.finngen.fi).

References

Gulamhusein AF, Hirschfield GM. Primary biliary cholangitis: pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(2):93–110.

Trivella J, John BV, Levy C. Primary biliary cholangitis: Epidemiology, prognosis, and treatment. Hepatol Commun 2023, 7(6).

Lv T, Chen S, Li M, Zhang D, Kong Y, Jia J. Regional variation and temporal trend of primary biliary cholangitis epidemiology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(6):1423–34.

Liu SP, Bian ZH, Zhao ZB, Wang J, Zhang W, Leung PSC, Li L, Lian ZX. Animal models of autoimmune liver diseases: a Comprehensive Review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;58(2):252–71.

Liwinski T, Heinemann M, Schramm C. The intestinal and biliary microbiome in autoimmune liver disease-current evidence and concepts. Semin Immunopathol. 2022;44(4):485–507.

Chalifoux SL, Konyn PG, Choi G, Saab S. Extrahepatic manifestations of primary biliary cholangitis. Gut Liver. 2017;11(6):771–80.

Wang CR, Tsai HW. Autoimmune liver diseases in systemic rheumatic diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(23):2527–45.

Efe C, Torgutalp M, Henriksson I, Alalkim F, Lytvyak E, Trivedi H, Eren F, Fischer J, Chayanupatkul M, Coppo C, et al. Extrahepatic autoimmune diseases in primary biliary cholangitis: prevalence and significance for clinical presentation and disease outcome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(4):936–42.

Selmi C, Generali E, Gershwin ME. Rheumatic manifestations in Autoimmune Liver Disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44(1):65–87.

Podgorska J, Werel P, Klapaczynski J, Orzechowska D, Wudarski M, Gietka A. Liver involvement in rheumatic diseases. Reumatologia. 2020;58(5):289–96.

Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1925–6.

Cordell HJ, Fryett JJ, Ueno K, Darlay R, Aiba Y, Hitomi Y, Kawashima M, Nishida N, Khor SS, Gervais O, et al. An international genome-wide meta-analysis of primary biliary cholangitis: novel risk loci and candidate drugs. J Hepatol. 2021;75(3):572–81.

Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, Sipila TP, Kristiansson K, Donner KM, Reeve MP, Laivuori H, Aavikko M, Kaunisto MA, et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature. 2023;613(7944):508–18.

Zhao J, Li K, Liao X, Zhao Q. Causal associations between inflammatory bowel disease and primary biliary cholangitis: a two-sample bidirectional mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10950.

Granito A, Muratori P, Muratori L, Pappas G, Cassani F, Worthington J, Ferri S, Quarneti C, Cipriano V, de Molo C, et al. Antibodies to SS-A/Ro-52kD and centromere in autoimmune liver disease: a clue to diagnosis and prognosis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(6):831–8.

Granito A, Muratori P, Muratori L, Pappas G, Cassani F, Worthington J, Guidi M, Ferri S, C DEM, Lenzi M, et al. Antinuclear antibodies giving the ‘multiple nuclear dots’ or the ‘rim-like/membranous’ patterns: diagnostic accuracy for primary biliary cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(11–12):1575–83.

Floreani A, De Martin S, Secchi MF, Cazzagon N. Extrahepatic autoimmunity in autoimmune liver disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;59:1–7.

Yang CY, Ma X, Tsuneyama K, Huang S, Takahashi T, Chalasani NP, Bowlus CL, Yang GX, Leung PS, Ansari AA, et al. IL-12/Th1 and IL-23/Th17 biliary microenvironment in primary biliary cirrhosis: implications for therapy. Hepatology. 2014;59(5):1944–53.

Selmi C, Gershwin ME. Chronic autoimmune epithelitis in Sjogren’s syndrome and primary biliary cholangitis: a Comprehensive Review. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4(2):263–79.

Bunte K, Beikler T. Th17 cells and the IL-23/IL-17 Axis in the Pathogenesis of Periodontitis and Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(14).

Akhter S, Tasnim FM, Islam MN, Rauf A, Mitra S, Emran TB, Alhumaydhi FA, Khalil AA, Aljohani ASM, Al Abdulmonem W, et al. Role of Th17 and IL-17 cytokines on inflammatory and auto-immune diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2023;29(26):2078–90.

Tang YY, Wang DC, Chen YY, Xu WD, Huang AF. Th1-related transcription factors and cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1305590.

Gan Y, Zhao X, He J, Liu X, Li Y, Sun X, Li Z. Increased Interleukin-17F is Associated with elevated autoantibody levels and more clinically relevant Than Interleukin-17A in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:4768408.

Petric M, Radic M. Is Th17-Targeted therapy effective in systemic Lupus Erythematosus? Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45(5):4331–43.

Wijarnpreecha K, Werlang M, Panjawatanan P, Kroner PT, Mousa OY, Pungpapong S, Lukens FJ, Harnois DM, Ungprasert P. Association between Smoking and Risk of primary biliary cholangitis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2019;28:197–203.

Chua MHY, Ng IAT, Mak MWLC. Association between Cigarette Smoking and systemic Lupus Erythematosus: an updated multivariate bayesian metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(10):1514–21.

Jin L, Dai M, Li C, Wang J, Wu B. Risk factors for primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2023;42(2):327–38.

Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Morinobu A, Kumagai S. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):70–81.

Premkumar M, Anand AC. Tobacco, cigarettes, and the liver: the Smoking Gun. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;11(6):700–12.

Harel-Meir M, Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Tobacco smoking and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(12):707–15.

De Luca F, Shoenfeld Y. The microbiome in autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;195(1):74–85.

Wang L, Cao ZM, Zhang LL, Li JM, Lv WL. The role of gut microbiota in some Liver diseases: from an immunological perspective. Front Immunol. 2022;13:923599.

Konig MF. The microbiome in autoimmune rheumatic disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;34(1):101473.

Horta-Baas G, Romero-Figueroa MDS, Montiel-Jarquin AJ, Pizano-Zarate ML, Garcia-Mena J, Ramirez-Duran N. Intestinal dysbiosis and rheumatoid arthritis: a link between Gut Microbiota and the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:4835189.

Tang R, Wei Y, Li Y, Chen W, Chen H, Wang Q, Yang F, Miao Q, Xiao X, Zhang H, et al. Gut microbial profile is altered in primary biliary cholangitis and partially restored after UDCA therapy. Gut. 2018;67(3):534–41.

Furukawa M, Moriya K, Nakayama J, Inoue T, Momoda R, Kawaratani H, Namisaki T, Sato S, Douhara A, Kaji K, et al. Gut dysbiosis associated with clinical prognosis of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Hepatol Res. 2020;50(7):840–52.

Miyauchi E, Shimokawa C, Steimle A, Desai MS, Ohno H. The impact of the gut microbiome on extra-intestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23(1):9–23.

Hitomi Y, Nakamura M. The Genetics of primary biliary cholangitis: a GWAS and Post-GWAS update. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14(2).

Ortiz-Fernandez L, Martin J, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. A Summary on the Genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, and Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2023;64(3):392–411.

Wang KS, Zorn E, Ritz J. Specific down-regulation of interleukin-12 signaling through induction of phospho-STAT4 protein degradation. Blood. 2001;97(12):3860–6.

Brune Z, Rice MR, Barnes BJ. Potential T Cell-Intrinsic Regulatory Roles for IRF5 via Cytokine Modulation in T Helper Subset differentiation and function. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1143.

Xu C, Wu Y, Liu N. Osteopontin in autoimmune disorders: current knowledge and future perspective. Inflammopharmacology. 2022;30(2):385–96.

Harada K, Ozaki S, Sudo Y, Tsuneyama K, Ohta H, Nakanuma Y. Osteopontin is involved in the formation of epithelioid granuloma and bile duct injury in primary biliary cirrhosis. Pathol Int. 2003;53(1):8–17.

Martin-Marquez BT, Sandoval-Garcia F, Corona-Meraz FI, Petri MH, Gutierrez-Mercado YK, Vazquez-Del Mercado M. Osteopontin: another piece in the systemic lupus erythematosus immunopathology puzzle. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40(1):173–82.

Gao X, Jia G, Guttman A, DePianto DJ, Morshead KB, Sun KH, Ramamoorthi N, Vander Heiden JA, Modrusan Z, Wolters PJ, et al. Osteopontin links myeloid activation and disease progression in systemic sclerosis. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1(8):100140.

Wang YH, Zhao MS, Zhao Y. [Expression of osteopontin in labial glands of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2012;44(2):236–9.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, HP.Z and Z.Z.; methodology, HP.Z.; software, HP.Z., Z.Z. and L.J; validation, Z.Z., HP.Z. and J.W.; formal analysis, HP.Z. and L.J; data curation, K.C and LF.X., HP. Z and L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, HP.Z.; writing—review and editing, HP.Z. and L.J; visualization, HP.Z., J.W and L.J. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, HP., Zhou, Z., Chen, K. et al. Primary biliary cholangitis has causal effects on systemic rheumatic diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Gastroenterol 24, 294 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03319-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03319-3