Abstract

Background

Frailty is a clinical syndrome of accelerated aging associated with adverse outcomes. Frailty is prevalent among patients with chronic kidney disease but is infrequently assessed in clinical settings, due to lack of consensus regarding frailty definitions and diagnostic tools. This study aimed to review the practice of frailty assessment in nephrology populations and evaluate the context and timing of frailty assessment.

Methods

The search included published reports of frailty assessment in patients with chronic kidney disease, undergoing dialysis or in receipt of a kidney transplant, published between January 2000 and November 2021. Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsychINFO, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were examined. A total of 164 articles were included for review.

Results

We found that studies were most frequently set within developed nations. Overall, 161 studies were frailty assessments conducted as part of an observational study design, and 3 within an interventional study. Studies favoured assessment of participants with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and transplant candidates. A total of 40 different frailty metrics were used. The most frequently utilised tool was the Fried frailty phenotype. Frailty prevalence varied across populations and research settings from 2.8% among participants with CKD to 82% among patients undergoing haemodialysis. Studies of frailty in conservatively managed populations were infrequent (N = 4). We verified that frailty predicts higher rates of adverse patient outcomes. There is sufficient literature to justify future meta-analyses.

Conclusions

There is increasing recognition of frailty in nephrology populations and the value of assessment in informing prognostication and decision-making during transitions in care. The Fried frailty phenotype is the most frequently utilised assessment, reflecting the feasibility of incorporating objective measures of frailty and vulnerability into nephrology clinical assessment. Further research examining frailty in low and middle income countries as well as first nations people is required. Future work should focus on interventional strategies exploring frailty rehabilitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

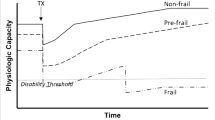

Frailty is a multisystem clinical syndrome resulting from the accumulation of vascular, inflammatory and age-related insults leading to accelerated aging, increased vulnerability to adverse outcomes and lack of functional reserve over time. There is growing interest in understanding the association between frailty and chronic kidney disease (CKD), a population increasingly characterised by advanced age and case complexity [1, 2].

Frailty is common among patients with kidney disease and becomes more prevalent as kidney disease progresses, even after adjustment for age and comorbidity [2, 3]. Frailty is related, but a separate construct, to chronological age, emerging in adults with organ failure at an earlier stage to the general population [4, 5]. For example, in an early study of patients undergoing haemodialysis (HD), 73% of the entire study cohort and 64% of those younger than 40 years of age exhibited frailty [6].

An emerging body of literature describes the clinical implications of frailty in nephrology populations including increased risk of hospitalisation and emergency department presentation, institutionalisation and death [7,8,9,10]. The presence of frailty out-performs conventional nephrology metrics in predicting kidney disease progression, renal replacement therapy choice, disease complications and patient-level outcomes [7, 11,12,13,14]. Routine use of frailty assessment to inform individualised management decisions has been endorsed as best practice by professional bodies but a consensus diagnostic approach remains to be resolved noting that an operational definition of frailty should be multi-dimensional [15,16,17].

While the medical syndrome of frailty is widely recognised, debate remains over how best to measure frailty in clinical and research settings. Many operational definitions have been introduced to distinguish frailty from “healthy aging”. These models differ in their conceptual foundations, clinical feasibility, frailty domains and their ability to characterise frailty as either a dichotomous or continuous variable. Other definitions distinguish physical frailty from social and cognitive frailty [18, 19]. To facilitate use in clinical settings, frailty assessments should be multi-dimensional, exclusive of the separate construct of disability, sensitive to dynamic changes in frailty status, predictive of relevant outcomes and feasible in resource-limited settings. There are further considerations unique to assessing patients with kidney disease. Within nephrology populations, definitions that emphasise weight loss such as the Fried phenotype [20] risk confounding by fluctuations in fluid status, while classification that incorporate fatigue may over-report frailty if assessed during the immediate post-dialysis period. The Frailty Index [21] is likewise subject to variations in performance relative to dialysis treatment, while the Clinical Frailty Scale [22] relies heavily on subjective clinical impression. Studies consistently demonstrate that self-reported measures over-estimate frailty in patients with kidney disease compared to objective criteria [23, 24], while nephrologist’s subjective assessment of frailty risks misclassification and discrimination, particularly for older patients and females [25]. Although objective assessment of frailty via performance-based measures such as Fried and the Short Physical Performance Battery form the foundation of comprehensive geriatric assessment, evaluations that can be extracted from the electronic medical record offer many advantages including reduced resource requirements and the ability to examine frailty retrospectively. Finally, performance-based tests of frailty may have limited utility in acute health-care settings when cardiovascular compromise or critical illness compel the use of questionnaire-based instruments.

Scoping reviews examining frailty assessment in acute care settings reveal inconsistent use of frailty tools with 89 different instruments applied [26]. To our knowledge, no scoping reviews have focussed on frailty measures in the CKD, dialysis and kidney transplant context. We argue that frailty reflects vulnerability and is not isolated to a specific modality of renal replacement therapy, and that because individual patients transition between different renal replacement therapy modalities and there is merit in comparing frailty assessment across CKD states. The aim of our scoping review was to examine and clarify key frailty concepts in the context of kidney disease, evaluate the most commonly utilised frailty assessment tools in nephrology research settings, describe the methodological contexts of frailty assessment and identify gaps in knowledge to guide future research work. Our focus is on the construct of physical frailty, acknowledging the existing scoping work exploring cognitive frailty in this patient population [27].

Methods

This scoping review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [28].

Selection criteria and search strategy

The search strategy was developed by AK and SR, with the assistance of a research librarian. This scoping review included original research articles published since January 2000 until November 30 2021. This timeframe was selected to reflect the emergence of the Frailty Phenotype and Frailty Index, developed in 2001, and following which the body of literature examining frailty expanded [20, 21]. This also coincides with the introduction of estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate which allowed for standardisation of CKD definitions [29]. The following inclusion criteria were applied to study selection: participants aged 18 years or older, diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, end stage kidney disease (ESKD) undergoing dialysis or managed conservatively, or undergoing evaluation for, or receipt of, a kidney transplant. Included studies were published in English language in a peer-reviewed journal. Exclusion criteria specified studies based on case reports or qualitative data, study populations with acute kidney injury and intensive care unit setting. As existing work has examined screening for cognitive impairment in dialysis populations [27], we also excluded papers examining cognitive frailty as a distinct construct. No specific patient outcomes were of interest as we sought to identify all adverse outcomes that the included studies reported on.

We searched Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsychINFO, PubMed and Cochrane Library. Additional articles were identified by searching the reference lists of systematic and literature reviews focusing on frailty in nephrology populations. Grey literature sources were not included. A search strategy was developed to identify frailty instruments, the population evaluated and context for the assessment (see Search Strategy in Supplemental Material). The search was performed on 30th November 2021. Backwards searching and hand searching (searching key references including systematic reviews for other relevant publications, as well as researcher-initiated database searches) were performed to interrogate the reliability of the search strategy. Identified papers were catalogued in EndNote, where duplicates were excluded, then imported to Colandr software (www.Colandrapp.com). Two members of the review team independently screened titles and abstracts that met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with reference to the inclusion criteria, seeking consensus in line with PRISMA-ScR Guidelines. Full-text review and data extraction was performed by all members of the reviewing team reviewers, with source data verification performed for 20% of the included articles to ensure reliability and replicability. The following data was extracted from each included article: year and country of publication, study design, study setting, number of participants, median duration of follow-up, nephrology population enrolled, dialysis vintage, participant age and sex, frailty measurement tool used, context of frailty assessment (when assessed and who completed evaluation), reason for measuring frailty, reported frailty scores, prevalence of frailty, outcome measures examined in relation to frailty.

Descriptive statistical analyses and graphics were conducted using Stata SE 17.0.

Results

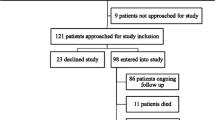

We found 1576 unique records using the search strategy. Full text was obtained for 389 articles. There were 164 studies comprising 116,005 participants meeting the inclusion criteria for final analysis. See Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. The included studies were published between 2004 and 2021, with the majority of studies published in the last 5 years (79%). The included studies were conducted across 18 countries, and 57 out of 164 studies, comprising 30,594 participants were conducted in the USA. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) high income countries were also over-represented. See Fig. 2.

The majority of the studies were prospective observational studies (91 studies), with 54 cross-sectional studies, 16 retrospective analyses and 3 randomised controlled trials. The focus of most of studies was to describe frailty as an outcome measure (104 studies). Frailty assessment was used for risk stratification purposes in 56 studies and formed study inclusion/exclusion criteria in 4 studies. There were 95 single-centre studies and 69 multicentre studies. The majority of studies enrolled more than 100 participants (119 studies).

Thirty-nine studies comprising 41,104 participants examined frailty in CKD populations [2, 3, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. Ninety-two studies comprising 26,332 participants enrolled HD populations [5, 6, 9, 10, 25, 30,31,32,33, 41, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146], 28 studies comprising 5545 participants examined peritoneal dialysis (PD) populations [6, 66,67,68,69,70,71, 73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83, 147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155] and 19 (35,308 participants) and 14 studies (7556 participants) were conducted in patients undergoing transplant assessment [5, 13, 156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172] or in receipt of a kidney transplant [5, 72, 156, 157, 173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182], respectively. Just four studies of 160 participants examined frailty in conservatively managed ESKD populations [71, 74, 77, 183]. See Fig. 3. Twenty-eight studies enrolled more than one nephrology population.

Mean age of participants was 62.3 ± 15.9 years, with older participants prevalent among CKD studies (75.6 ± 11.4 years) and conservatively managed populations (78.0 ± 7.0 years). Transplant candidates and transplant recipients were, on average, younger (54.3 ± 13.3 years and 53.5 ± 14.1 years, respectively). Males outnumbered females in all studies except for conservatively managed populations.

Frailty assessment

Frailty assessment characteristics of the included studies are presenting in Table 2. Context of frailty assessment was, in general, poorly described in studies with 61% of studies failing to describe timing of frailty assessment and 64.6% of studies not reporting who performed the frailty assessment. Where included studies provided this detail, 16 studies (41%) examined frailty in participants with CKD in outpatient settings while transplant candidates where most frequently assessed at admission for transplantation operation (8 studies, 53.3% of studies). Assessments for frailty were most commonly performed by researchers rather than clinical staff (51 studies, 31%).

A total of 40 different frailty metrics were used across 164 studies. Most studies included only one frailty measure (n = 107), while 27 studies employed 2 different frailty metrics. Thirty studies included 3 or more frailty measures. The most frequently utilised tool for frailty assessment was Fried frailty phenotype with 90 studies (54.9%) utilising this metric (Table 2). Clinical Frailty Scale was also frequently used (29 studies), particularly among PD populations. Six studies reported subjective clinical assessments by doctors and 4 studies reported nursing staff clinical impression. Patient perception was sought in one study and 1 study reported caregiver perception. An in-house questionnaire of Chinese PD populations [153] was used in 6 Chinese PD studies. Comprehensive geriatric assessment was infrequently used across study populations (4.9% of studies).

One hundred and forty-five studies reported frailty prevalence rate. Fried frailty prevalence varied across studies and study populations, with highest prevalence of Fried-phenotype frailty reported in HD (5.6% to 82%) and PD (27.3% to 76%) populations and lower Fried-phenotype frailty evident in studies evaluating participants with CKD (2.8% to 44.4%), transplant candidates (13.3% to 23.4%) and transplant recipients (15.7% to 37%) (see Fig. 4a-e). Study population demographics are presented in Supplemental Tables 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, demonstrating the heterogenous study population characteristics, particularly in studies focussing on CKD and HD populations. Only one study utilising Fried phenotype reported prevalence within conservatively managed populations, describing a prevalence rate of 62% [71]. Use of Fried phenotype in six studies facilitated description of an intermediately or pre-frail frail patient population, reporting a prevalence rate of 28.4–37.7% [9, 122, 162, 179, 180].

Prevalence of frailty based on other assessment tools is presented in Supplemental Materials, stratified by study population. We present a comparison of these reported prevalence rates where a consistent tool is used in three or more published studies. Frailty prevalence varies both by study population and frailty metric.

Six studies performed frailty assessment at more than one time point, demonstrating frailty progression and increase in frailty prevalence within the CKD and PD study cohorts followed for mean 45.7 ± 6.0 months [149], at 12 and 24 months of follow-up median 4 years [59] and unspecified [184]. One study of HD patients assessed at baseline, 12 months and 24 months follow-up demonstrated improvement in frailty parameters as often as worsening [109]. Among transplant patients, serial frailty assessment demonstrated improvement [178] or varied responses [159] following kidney transplantation.

Frailty outcomes

Frailty was found to be predictive of patient outcomes in 133 of 143 studies that evaluated clinical sequelae. Forty studies reported that frailty predicted mortality outcomes [6, 9, 10, 30, 37, 39, 46, 52, 61, 65, 66, 69, 72, 75, 83, 84, 92, 95, 97, 100, 104, 109, 110, 124, 145, 147, 152,153,154,155, 157, 159, 162, 163, 166, 175, 180, 182, 185, 186] and 16 studies found frailty was associated with hospitalisation [6, 9, 10, 30, 41, 46, 66, 69, 81, 83, 84, 116, 138, 153, 154, 177]. Three studies reported frailty predicted increased likelihood of in-centre HD modality choice compared to a home-based dialysis modality [39, 61, 187]. Eight studies reported frailty was associated with reduced likelihood of transplant referral and waitlisting, removal from waitlist or death on waitlist [66, 75, 150, 158, 160, 161, 165, 188] while four studies reported an association with post-transplant complications [168, 173, 175, 179].

Four studies compared and reported on the sensitivity and specificity of different frailty metrics, comparing them to a gold standard, alternatively defined as comprehensive geriatric assessment [136], Frailty Index [33, 76] and Fried phenotype [58]. These studies report the Clinical Frailty Scale [76] and Fried phenotype are highly specific [136], but with corresponding lower sensitivity, and that the Groningen Frailty index has comparable discriminatory ability [33]. Subjective frailty assessments based on self-rated health and a Surprise Question have a high negative predict value, useful for excluding frailty [58].

Discussion

This scoping review synthesises the published literature concerned with frailty assessment in a number of diverse nephrology populations. We found this to be an emerging field of research with most studies conducted in the last 6 years. Published literature to date has extensively examined CKD populations, dialysis and transplant populations but few studies have examined conservatively managed patients with end stage kidney disease. This differs markedly from clinical practice where conservatively managed patients seeking renal supportive care or palliative care are a major focus of frailty assessment [189]. Patients engaged in PD are also underexamined by the current published literature exploring frailty, as has been reported elsewhere [190]. Frailty occurs with high but variable prevalence among CKD and dialysis populations, revealing study population heterogeneity and utilisation of different frailty metrics with varying sensitivities. Frailty is less prevalent among patients undergoing evaluation for transplant candidacy and transplant recipients, likely reflecting clinicians’ awareness of the implications of frailty in transplant outcomes and the health economics informing transplant allocation. There is robust evidence that frailty is a risk factor for adverse clinical outcomes, suggesting that frailty assessment may improve risk stratification and advance communication in clinical interactions. The focus of studies performed to date has been descriptive and prognostic, with little research activity exploring interventions for frailty rehabilitation.

Study settings reveal an over-representation of middle- and higher-income countries where frailty is likely to be less prevalent. There is little exploration of frailty in first-nations people, reinforcing concerns that frailty phenotype in indigenous populations may be under-recognised and contribute to inequities in health care delivery [191, 192]. Study populations demonstrate under-representation of female patients, despite recognition that female gender increases odds of frailty [81].

Frailty may be assessed either by subjective (self-reported or clinician perception) or objective means, using direct measurement of physical performance or exploiting descriptive tools with clear categorical definitions. Overall, there were 40 different frailty measures used across 164 studies. The range of instruments utilised by studies included in this review reflects the lack of consensus regarding the best instruments for assessing frailty [193, 194]. This heterogeneity has similarly been reported by scoping reviews examining frailty assessment in acute care settings [26] and solid organ transplantation [195]. Assessment settings and contexts were poorly described across studies, although the majority of studies that did provide this detail indicated a propensity for CKD patient assessment in the outpatient setting, while transplant candidates were most commonly assessed at admission for kidney transplantation surgery. The utilisation of frailty assessments in these settings suggests capacity and feasibility to incorporate frailty evaluation into routine fast-paced high-turnover nephrology assessment.

A small number of studies evaluated frailty at more than one time point, demonstrating, in general, a progression and increase in frailty prevalence among CKD and dialysis cohorts. In contrast, those studies exploring frailty dynamics in transplant populations reported improvement in frailty parameters or mixed but nonetheless changes in frailty state post transplantation. There were no studies reporting on frailty progression or rehabilitation over the course of an acute hospital admission. Assessment from frailty in the hospital setting has a number of challenges due to the severity of health status of hospitalised older adults, risk of delirium and medication changes as well as pragmatic considerations of the environment [196]. Nonetheless, acute hospital admission is a well-recognised risk factor for frailty progression within the geriatric literature [196,197,198]. As commentators on this issue point out, it is only with the implementation of frailty assessment as hospital admission that we can prevent the emergence of new cases of frailty and the occurrence of adverse outcomes [199]. It has been reported that frequent hospitalisation among patients undergoing HD is associated with greater frailty at any point and worsening frailty over time [109, 200], but how frailty behaves across an acute admission event among patients with kidney disease remains unknown. Especially relevant for nephrology populations prone to frequent hospitalisation events, studies that examine the frailty syndrome at discharge and following hospitalisation compared to admission are necessary to identify the occurrence of transitions between degrees of frailty (progression and reversion) and understand how frailty can be remedied.

Frailty assessment was predominantly performed by specifically enlisted research staff, with infrequent assessment by clinical or allied health professionals. Where clinicians were involved in the assessment of frailty, this favoured subjective assessment, a measure previously demonstrated to be unreliable with a high risk of bias [25].This suggests a need to build capacity and experience within the nephology workforce in objective frailty clinical assessment. The patient and caregiver perspectives of frailty remain under-explored.

In this review, the most frequently used instrument for assessing frailty was the Fried frailty phenotype which combines self-reported components (fatigue/exhaustion, low physical activity) alongside assessments of physical function (grip strength, walk speed) and biometrics (unintentional weight loss). The Clinical Frailty Scale lends itself well to retrospective analyses and was favoured by studies utilising this methodology. Frailty Index was frequently utilised in CKD studies where competing comorbidities were of greater or equivalent relevance. Of note, frailty metrics borrowed from palliative care such as the Karnovsky and Surprise Question were infrequently used in research settings. Chinese PD studies favoured the use of the in-house questionnaire but its utility outside of this population demographic remains untested. Frailty assessments among participants with solid organ transplant populations favour the Fried frailty phenotype [195] while geriatric publications have preferred the Frailty Index [199]. Assessments in acute care settings have equally relied on the Fried frailty phenotype, Frailty Index and Clinical Frailty Scale [26]. It is likely that different instruments offer distinctive advantages in varied clinical settings.

We were able to compare rates of Fried frailty reported in different study settings. This analysis demonstrates highly variable rates of frailty, particularly among CKD and HD populations, likely reflecting heterogenous population characteristics as well as differences in health care access and policy.

Use of the Fried phenotype afforded description of intermediately frail or pre-frail patients in six studies, suggesting greater flexibility for this frailty assessment tool. The Frailty Index, FRAIL scale, Cardiovascular Health Study Index and Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Index also have the capacity to define intermediate states off frailty but was rarely utilised by included studies. The rates of pre-frailty reported among nephrology populations corresponds with similar prevalence of pre-frailty reported in the geriatric literature [201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210]. Importantly, pre-frailty is a dynamic state with the potential for reversion to the state of robustness [20, 211], suggesting the opportunity for early intervention to improve or maintain health status and prevent functional decline.

We verified that frailty predicts higher risk of adverse patient outcomes including mortality, hospitalisation, restricted renal replacement therapy choice, reduced likelihood of transplantation and post-transplantation complications. Earlier systematic review reported similar adverse outcomes [212]. We propose that there is now sufficient literature exploring kidney disease and frailty outcomes to justify future meta-analysis.

Whether early identification of frailty will allow intervention and treatment remains to be seen. Frailty management guidelines focus on community dwelling older adults [213, 214]. The importance of frailty is also recognised by the discipline of cardiology where an “Essential frailty toolkit” and consensus documents specifying strategies for primary, secondary and tertiary frailty prevention guide management [215,216,217]. This review highlights a critical lack of interventional studies exploring frailty management strategies.

The broad scope of this review emerges as a strength, allowing clinicians and researchers to consider the evidence relevant to their individual patient and their position with CKD states. This scoping review was restricted to studies published in English, potentially leading to underrepresentation of the non-English speaking population and the value of non-English frailty instruments. We sought to apply quality controls by including only papers which had undergone robust peer review processes. Through exclusion of conference abstracts, we may have missed contemporary research, thereby limiting the applicability of our conclusions. By design, scoping reviews do not contain a quality of evidence assessment and this review subsequently provides a descriptive study of available research, including gaps in evidence. Furthermore, our review excluded studies set within ICU and performed in patients with acute kidney injury; our findings do not apply to these patient populations.

Conclusions

This scoping review describes a rapidly proliferating body of literature concerned with frailty in nephrology populations. We verify a high prevalence of frailty among heterogeneous patient populations and the utilisation of a variety of assessment tools in diverse research settings. The Fried frailty phenotype is the most commonly used frailty metric, characterised by a high specificity and facilitating the valuable identification of a vulnerable pre-frail state. There is robust evidence that frailty predicts adverse patient outcomes and may augment traditional risk-stratification and decision-making tools in nephrology clinical practice. There is a need for further studies examining frailty in culturally and linguistically diverse populations and an urgent need for interventional research exploring frailty rehabilitation strategies.

Availability of data and materials

As a scoping review, raw data are available from the individual publications included in the reference list. Further detail is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- Conservative:

-

Conservatively managed kidney disease

- ESKD:

-

End stage kidney disease

- HD:

-

Haemodialysis

- PD:

-

Peritoneal dialysis

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

References

Sy J, Johansen KL. The impact of frailty on outcomes in dialysis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26(6):537–42.

Roshanravan B, Khatri M, Robinson-Cohen C, Levin G, Patel KV, De Boer IH, et al. A prospective study of frailty in nephrology-referred patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(6):912–21.

Hubbard RE, Peel NM, Smith M, Dawson B, Lambat Z, Bak M, et al. Feasibility and construct validity of a Frailty index for patients with chronic kidney disease. Australas J Ageing. 2015;34(3):E9–12.

Kojima G. Prevalence of frailty in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(11):1989–97.

Chu NM, Chen X, Norman SP, Fitzpatrick J, Sozio SM, Jaar BG, et al. Frailty prevalence in younger end-stage kidney disease patients undergoing dialysis and transplantation. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51(7):501–10.

Bao Y, Dalrymple L, Chertow GM, Kaysen GA, Johansen KL. Frailty, dialysis initiation, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1071–7.

Roshanravan B, Robinson-Cohen C, Patel KV, Ayers E, Littman AJ, de Boer IH, et al. Association between physical performance and all-cause mortality in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(5):822–30.

Beddhu S, Baird BC, Zitterkoph J, Neilson J, Greene T. Physical activity and mortality in chronic kidney disease (NHANES III). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2009;4(12):1901–6.

McAdams-Demarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, Boyarsky B, Gimenez L, Jaar BG, et al. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):896–901.

Garcia-Canton C, Rodenas A, Lopez-Aperador C, Rivero Y, Anton G, Monzon T, et al. Frailty in hemodialysis and prediction of poor short-term outcome: mortality, hospitalization and visits to hospital emergency services. Ren Fail. 2019;41(1):567–75.

Clark D, Matheson K, West B, Vinson A, West K, Jain A, et al. Frailty severity and hospitalization after dialysis initiation. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:20543581211023330.

Findlay MD, Donaldson K, Doyle A, Fox JG, Khan I, McDonald J, et al. Factors influencing withdrawal from dialysis: a national registry study. Nephrol Dialy Transplant. 2016;31(12):2041–8.

Haugen CE, Chu NM, Ying H, Warsame F, Holscher CM, Desai NM, et al. Frailty and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc of Nephrol : CJASN. 2019;14(4):576–82.

Foote C, Morton RL, Jardine M, Gallagher M, Brown M, Howard K, et al. COnsiderations of nephrologists when suggesting dialysis in elderly patients with renal failure (CONSIDER): a discrete choice experiment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(12):2302–9.

Kobashigawa J, Dadhania D, Bhorade S, Adey D, Berger J, Bhat G, et al. Report from the American society of transplantation on frailty in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2019;19(4):984–94.

Farrington K, Covic A, Nistor I, Aucella F, Clyne N, De Vos L, et al. Clinical practice guideline on management of older patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3b or higher (eGFR<45 mL/min/1.73 m2): a summary document from the European renal best practice group. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(1):9–16.

Rodríguez-Mañas L, Féart C, Mann G, Viña J, Chatterji S, Chodzko-Zajko W, et al. Searching for an operational definition of frailty: a Delphi method based consensus statement: the frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(1):62–7.

Bunt S, Steverink N, Olthof J, van der Schans CP, Hobbelen JSM. Social frailty in older adults: a scoping review. Eur J Ageing. 2017;14(3):323–34.

Ruan Q, Yu Z, Chen M, Bao Z, Li J, He W. Cognitive frailty, a novel target for the prevention of elderly dependency. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;20:1–10.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–7.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J = J de l’Assoc Med Can. 2005;173(5):489–95.

Painter P, Roshanravan B. The association of physical activity and physical function with clinical outcomes in adults with chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22(6):615–23.

Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Kornak J, Grimes B, et al. Comparison of self-report-based and physical performance-based frailty definitions among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(4):600–7.

Salter ML, Gupta N, Massie AB, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law AH, Jacob RL, et al. Perceived frailty and measured frailty among adults undergoing hemodialysis: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:52.

Theou O, Squires E, Mallery K, Lee JS, Fay S, Goldstein J, et al. What do we know about frailty in the acute care setting? A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):139.

San A, Hiremagalur B, Muircroft W, Grealish L. Screening of cognitive impairment in the dialysis population: a scoping review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2017;44(3–4):182–95.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of diet in renal disease study group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–70.

Nixon AC, Brown J, Brotherton A, Harrison M, Todd J, Brannigan D, et al. Implementation of a frailty screening programme and Geriatric Assessment Service in a nephrology centre: a quality improvement project. J Nephrol. 2021;34(4):1215–24.

Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, Mitra S, Brady ME, Dhaygude AP. Frailty is independently associated with worse health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: a secondary analysis of the frailty assessment in chronic kidney disease study. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(1):85–94.

Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, Mitra S, Dhaygude AP. Diagnostic accuracy of frailty screening methods in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron. 2019;141(3):147–55.

Van Munster BC, Drost D, Kalf A, Vogtlander NP. Discriminative value of frailty screening instruments in end-stage renal disease. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9(4):606–10.

Vettoretti S, Caldiroli L, Porata G, Vezza C, Cesari M, Messa P. Frailty phenotype and multi-domain impairments in older patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):371.

Chan GC, Than WH, Kwan BC, Lai KB, Chan RC, Ng JK, et al. Adipose expression of miR-130b and miR-17-5p with wasting, cardiovascular event and mortality in advanced chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37(10):1935–43.

Kumarasinghe AP, Chakera A, Chan K, Dogra S, Broers S, Maher S, et al. Incorporating the clinical frailty scale into routine outpatient nephrology practice: an observational study of feasibility and associations. Intern Med J. 2021;51(8):1269–77.

Pugh J, Aggett J, Goodland A, Prichard A, Thomas N, Donovan K, et al. Frailty and comorbidity are independent predictors of outcome in patients referred for pre-dialysis education. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9(2):324–9.

Pyart R, Aggett J, Goodland A, Jones H, Prichard A, Pugh J, et al. Exploring the choices and outcomes of older patients with advanced kidney disease. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6): e0234309.

Wong WS, Manssouri A, Robb J, Cousland Z, Dingwall K, Brennan A. Use of clinical frailty scale in patients with chronic kidney disease stage 4/5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(SUPPL 3):iii493.

Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Gooch HJ, Young HML, Finlayson KW, Pendleton N, et al. Home-based exercise for people living with frailty and chronic kidney disease: A mixed-methods pilot randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7): e0251652.

Lee SW, Lee A, Yu MY, Kim SW, Kim KI, Na KY, et al. Is frailty a modifiable risk factor of future adverse outcomes in elderly patients with incident end-stage renal disease? J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(11):1800–6.

Adame Perez SI, Senior PA, Field CJ, Jindal K, Mager DR. Frailty, health-related quality of life, cognition, depression, vitamin D and health-care utilization in an ambulatory adult population with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional analysis. Can J Diabetes. 2019;43(2):90–7.

Chen SI, Chiang CL, Chao CT, Chiang CK, Huang JW. Gustatory dysfunction is closely associated with frailty in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Renal Nutr. 2021;31(1):49–56.

Yamada M, Arai H, Nishiguchi S, Kajiwara Y, Yoshimura K, Sonoda T, et al. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an independent risk factor for long-term care insurance (LTCI) need certification among older Japanese adults: a two-year prospective cohort study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57(3):328–32.

Miller LM, Rifkin D, Lee AK, Kurella Tamura M, Pajewski NM, Weiner DE, et al. Association of urine biomarkers of kidney tubule injury and dysfunction with frailty index and cognitive function in persons With CKD in SPRINT. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(4):530-40.e1.

Vezza C, Vettoretti S, Caldiroli L, Bergamaschini L, Messa P, Cesari M. Use of the frailty index in older persons with chronic kidney disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(9):1179–80.

Jovanovich A, Ginsberg C, You Z, Katz R, Ambrosius WT, Berlowitz D, et al. FGF23, frailty, and falls in SPRINT. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(2):467–73.

Dalrymple LS, Katz R, Rifkin DE, Siscovick D, Newman AB, Fried LF, et al. Kidney function and prevalent and incident frailty. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2013;8(12):2091–9.

Delgado C, Shieh S, Grimes B, Chertow GM, Dalrymple LS, Kaysen GA, et al. Association of self-reported frailty with falls and fractures among patients new to dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 2015;42(2):134–40.

Kosaka S, Ohara Y, Naito S, Iimori S, Kado H, Hatta T, et al. Association among kidney function, frailty, and oral function in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):357.

Nixon AC, Wilkinson TJ, Young HML, Taal MW, Pendleton N, Mitra S, et al. Symptom-burden in people living with frailty and chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):411.

Wilhelm-Leen ER, Hall YN, Tamura MK, Chertow GM. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: the third national health and nutrition evaluation survey. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):664-71.e2.

Lorenz EC, Hickson LJ, Weatherly RM, Thompson KL, Walker HA, Rasmussen JM, et al. Protocolized exercise improves frailty parameters and lower extremity impairment: a promising prehabilitation strategy for kidney transplant candidates. Clin Transplant. 2020;34(9): e14017.

Margiotta E, Miragoli F, Callegari ML, Vettoretti S, Caldiroli L, Meneghini M, et al. Gut microbiota composition and frailty in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4): e0228530.

Coppolino G, Bolignano D, Gareri P, Ruberto C, Andreucci M, Ruotolo G, et al. Kidney function and cognitive decline in frail elderly: two faces of the same coin? Int Urol Nephrol. 2018;50(8):1505–10.

Rodriguez Villarreal I, Ortega O, Hinostroza J, Cobo G, Gallar P, Mon C, et al. Geriatric assessment for therapeutic decision-making regarding renal replacement in elderly patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;128(1–2):73–8.

Shlipak MG, Stehman-Breen C, Fried LF, Song X, Siscovick D, Fried LP, et al. The presence of frailty in elderly persons with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5):861–7.

Baddour NA, Robinson-Cohen C, Lipworth L, Bian A, Stewart TG, Jhamb M, et al. The surprise question and self-rated health are useful screens for frailty and disability in older adults with chronic kidney disease. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(12):1522–9.

Ghazi L, Yaffe K, Tamura MK, Rahman M, Hsu CY, Anderson AH, et al. Association of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure patterns with cognitive function and physical functioning in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(4):452–64.

Brar RS, Whitlock RH, Komenda PVJ, Rigatto C, Prasad B, Bohm C, et al. Provider perception of frailty is associated with dialysis decision making in patients with advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2021;16(4):552–9.

Whitlock R, Eng F, Brar RS, Rigatto C, Komenda P, Bohm C, et al. Frailty affects treatment decisions and outcomes for patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:532.

Inoue T, Shinjo T, Matsuoka M, Tamashiro M, Oba K, Arasaki O, et al. The association between frailty and chronic kidney disease; cross-sectional analysis of the Nambu cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2021;25(12):1311–8.

Mansur HN, Colugnati FA, Grincenkov FR, Bastos MG. Frailty and quality of life: a cross-sectional study of Brazilian patients with pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:27.

Lee SJ, Son H, Shin SK. Influence of frailty on health-related quality of life in pre-dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease in Korea: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:70.

Ali H, Abdelaziz T, Abdelaal F, Baharani J. Assessment of prevalence and clinical outcome of frailty in an elderly predialysis cohort using simple tools. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29(1):63–70.

Jegatheswaran J, Chan R, Hiremath S, Moorman D, Suri RS, Ramsay T, et al. Use of the FRAIL questionnaire in patients with end-stage kidney disease. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120952904 no pagination.

Iyasere O, Brown E, Gordon F, Collinson H, Fielding R, Fluck R, et al. Longitudinal trends in quality of life and physical function in frail older dialysis patients: a comparison of assisted peritoneal dialysis and in-center hemodialysis. Peritoneal Dial Int. 2019;39(2):112–8.

Iyasere OU, Brown EA, Johansson L, Huson L, Smee J, Maxwell AP, et al. Quality of life and physical function in older patients on dialysis: a comparison of assisted peritoneal dialysis with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2016;11(3):423–30.

Lee SY, Yang DH, Hwang E, Kang SH, Park SH, Kim TW, et al. The prevalence, association, and clinical outcomes of frailty in maintenance dialysis patients. J Renal Nutr. 2017;27(2):106–12.

Goto NA, van Loon IN, Boereboom FTJ, Emmelot-Vonk MH, Willems HC, Bots ML, et al. Association of initiation of maintenance dialysis with functional status and caregiver burden. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2019;14(7):1039–47.

Goto NA, van Loon IN, Morpey MI, Verhaar MC, Willems HC, Emmelot-Vonk MH, et al. Geriatric assessment in elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease. Nephron. 2019;141(1):41–8.

Neradova A, Vajgel G, Hendra H, Antonelou M, Kostakis ID, Wright D, et al. Frailty score before admission as risk factor for mortality of renal patients during the first wave of the COVID pandemic in London. G Ital Nefrol. 2021;38(3):2021.

Sclauzero P, Galli G, Barbati G, Carraro M, Panzetta GO. Role of components of frailty on quality of life in dialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. J Ren Care. 2013;39(2):96–102.

Iyasere O, Brown EA, Johansson L, Davenport A, Farrington K, Maxwell AP, et al. Quality of life with conservative care compared with assisted peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2019;12(2):262–8.

Alfaadhel TA, Soroka SD, Kiberd BA, Landry D, Moorhouse P, Tennankore KK. Frailty and mortality in dialysis: evaluation of a clinical frailty scale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(5):832–40.

Clark DA, Khan U, Kiberd BA, Turner CC, Dixon A, Landry D, et al. Frailty in end-stage renal disease: comparing patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives. BMC Nephrology. 2017;18(1):148 (no pagination).

Tan T, Brennan F, Brown MA. Impact of dialysis on symptom burden and functional state in the elderly. Renal Soc Austral J. 2017;13(1):22–30.

Kang SH, Do JY, Jeong HY, Lee SY, Kim JC. The clinical significance of physical activity in maintenance dialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42(3):575–86.

Moreno-Useche L, Urrego-Rubio J, Cadena-Sanabria M, Rodríguez Amaya R, Maldonado-Navas S, Ruiz GC. Frailty syndrome in patients with chronic kidney disease at a dialysis centre from Santander Colombia. J Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;69:1–7.

Drost D, Kalf A, Vogtlander N, van Munster BC. High prevalence of frailty in end-stage renal disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48(8):1357–62.

Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2960–7.

Vinson AJ, Bartolacci J, Goldstein J, Swain J, Clark D, Tennankore KK. Predictors of need for first and recurrent emergency medical service transport to emergency department after dialysis initiation. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(6):822–30.

Van Loon IN, Goto NA, Boereboom FTJ, Bots ML, Hoogeveen EK, Gamadia L, et al. Geriatric assessment and the relation with mortality and hospitalizations in older patients starting dialysis. Nephron. 2019;143(2):108–19.

Bancu I, Graterol F, Bonal J, Fernandez-Crespo P, Garcia J, Aguerrevere S, et al. Frail patient in hemodialysis: a new challenge in nephrology-incidence in our area, Barcelones Nord and Maresme. J Aging Res. 2017;2017:7624139.

Camilleri S, Chong S, Tangvoraphonkchai K, Yoowannakul S, Davenport A. Effect of self-reported distress thermometer score on the maximal handgrip and pinch strength measurements in hemodialysis patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017;32(5):682–6.

Chao CT, Huang JW. Frailty severity is significantly associated with electrocardiographic QRS duration in chronic dialysis patients. PeerJ. 2015;3: e1354.

Chao CT, Hsu YH, Chang PY, He YT, Ueng RS, Lai CF, et al. Simple self-report FRAIL scale might be more closely associated with dialysis complications than other frailty screening instruments in rural chronic dialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2015;20(5):321–8.

Chao CT, Huang JW, Chiang CK. Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-the fatigue scale exhibits stronger associations with clinical parameters in chronic dialysis patients compared to other fatigue-assessing instruments. PeerJ. 2016;4: e1818.

Chao CT, Huang JW. Geriatric syndromes are potential determinants of the medication adherence status in prevalent dialysis patients. PeerJ. 2016;4: e2122.

Chao CT, Lai HJ, Tsai HB, Yang SY, Huang JW. Frail phenotype is associated with distinct quantitative electroencephalographic findings among end-stage renal disease patients: an observational study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):277.

Chao CT, Huang JW, Chan DC. Frail phenotype might herald bone health worsening among end-stage renal disease patients. PeerJ. 2017;5: e3542.

Chao CT, Huang JW, Chiang CK, Hung KY. Applicability of laboratory deficit-based frailty index in predominantly older patients with end-stage renal disease under chronic dialysis: A pilot test of its correlation with survival and self-reported instruments. Nephrology. 2020;25(1):73–81.

Chiang JM, Kaysen GA, Segal M, Chertow GM, Delgado C, Johansen KL. Low testosterone is associated with frailty, muscle wasting and physical dysfunction among men receiving hemodialysis: a longitudinal analysis. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2019;34(5):802–10.

Delgado C, Doyle JW, Johansen KL. Association of frailty with body composition among patients on hemodialysis. J Renal Nutr. 2013;23(5):356–62.

Fitzpatrick J, Sozio SM, Jaar BG, Estrella MM, Segev DL, Parekh RS, et al. Frailty, body composition and the risk of mortality in incident hemodialysis patients: the predictors of arrhythmic and cardiovascular risk in end stage renal disease study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(2):346–54.

Fitzpatrick J, Sozio SM, Jaar BG, Estrella MM, Segev DL, Shafi T, et al. Frailty, age, and postdialysis recovery time in a population new to hemodialysis. Kidney360. 2021;2(9):1455–62.

Fu W, Zhang A, Ma L, Jia L, Chhetri JK, Chan P. Severity of frailty as a significant predictor of mortality for hemodialysis patients: A prospective study in China. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(14):3309–17.

Gesualdo GD, Duarte JG, Zazzetta MS, Kusumota L, Orlandi FS. Frailty and associated risk factors in patients with chronic kidney disease on dialysis. Ciencia Saude Coletiva. 2020;25(11):4631–7.

Gopinathan JC, Hafeeq B, Aziz F, Narayanan S, Aboobacker IN, Uvais NA. The prevalence of frailty and its association with cognitive dysfunction among elderly patients on maintenance hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study from South India. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2020;31(4):767–74.

Hasegawa J, Kimachi M, Kurita N, Kanda E, Wakai S, Nitta K. The normalized protein catabolic rate and mortality risk of patients on hemodialysis by frailty status: the Japanese dialysis outcomes and practice pattern study. J Renal Nutr. 2020;30(6):535–9.

Hendra H, Vajgel G, Antonelou M, Neradova A, Manson B, Clark SG, et al. Identifying prognostic risk factors for poor outcome following COVID-19 disease among in-centre haemodialysis patients: role of inflammation and frailty. J Nephrol. 2021;34(2):315–23.

Hernandez-Agudelo SY, Musso CG, González-Torres HJ, Castro-Hernández C, Maya-Altamiranda LP, Quintero-Cruz MV, et al. Optimizing dialysis dose in the context of frailty: an exploratory study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53(5):1025–31.

Hornik B, Duława J. Frailty, quality of life, anxiety, and other factors affecting adherence to physical activity recommendations by hemodialysis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1827.

Hwang D, Lee E, Yoo BC, Park S, Choi KJ, Oh S, et al. Validation of risk prediction tools in elderly patients who initiate dialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51(7):1231–8.

Jafari M, Kour K, Giebel S, Omisore I, Prasad B. The burden of frailty on mood, cognition, quality of life, and level of independence in patients on hemodialysis: regina hemodialysis frailty study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120917780.

Jafari M, Anwar S, Kour K, Sanjoy S, Goyal K, Prasad B. T scores, FRAX, frailty phenotype, falls, and its relationship to fractures in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:20543581211041184.

Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Kornak J, Grimes B, et al. Association between body composition and frailty among prevalent hemodialysis patients: a US renal data system special study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(2):381–9.

Johansen KL, Painter P, Delgado C, Doyle J. Characterization of physical activity and sitting time among patients on hemodialysis using a new physical activity instrument. J Renal Nutr. 2015;25(1):25–30.

Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Glidden D, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Grimes B, et al. Association of performance-based and self-reported function-based definitions of frailty with mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(4):626–32.

Johansen KL, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Chertow GM, Chiang J, Dalrymple LS, et al. Frailty among patients receiving hemodialysis: evolution of components and associations with mortality. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(3):380–6.

Kakio Y, Uchida HA, Takeuchi H, Okuyama Y, Okuyama M, Umebayashi R, et al. Diabetic nephropathy is associated with frailty in patients with chronic hemodialysis. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(12):1597–602.

Kimura H, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Rhee CM, Streja E, Sy J. Polypharmacy and frailty among hemodialysis patients. Nephron. 2021;145(6):624–32.

Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Wasse H. Falls among hemodialysis patients: potential opportunities for prevention? Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(3):257–63.

Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, McClellan WM, Soltow QA, Lea J. Risk factors for frailty in a large prevalent cohort of hemodialysis patients. Am J Med Sci. 2014;348(4):277–82.

Kutner NG, Zhang R, Allman RM, Bowling CB. Correlates of ADL difficulty in a large hemodialysis cohort. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2014;18(1):70–7.

Li Y, Zhang D, Ma Q, Diao Z, Liu S, Shi X. The impact of frailty on prognosis in elderly hemodialysis patients: a prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1659–67.

Lin HC, Cai ZS, Huang JT, Chen MJ. The correlation between frailty and recurrent vascular access failure in the elderly maintenance hemodialysis patients. Int J Gerontol. 2020;14:159–62.

Lo D, Chiu E, Jassal SV. A prospective pilot study to measure changes in functional status associated with hospitalization in elderly dialysis-dependent patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(5):956–61.

Lunney M, Wiebe N, Kusi-Appiah E, Tonelli A, Lewis R, Ferber R, et al. Wearable fitness trackers to predict clinical deterioration in maintenance hemodialysis: a prospective cohort feasibility study. Kidney Med. 2021;3(5):768-75.e1.

Matsuzawa R, Suzuki Y, Yamamoto S, Harada M, Watanabe T, Shimoda T, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life and physical performance-based components of frailty in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Renal Nutr. 2021;31(5):529–36.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Suresh S, Law A, Salter ML, Gimenez LF, Jaar BG, et al. Frailty and falls among adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:224.

McAdams-Demarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, Gross A, Meoni LA, Jaar BG, et al. Frailty and cognitive function in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2181–9.

Miyazaki S, Iino N, Koda R, Narita I, Kaneko Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is associated with sarcopenia and frailty in Japanese hemodialysis patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(1):27–33.

Moorthi RN, Fadel WF, Cranor A, Hindi J, Avin KG, Lane KA, et al. Mobility impairment in patients new to dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51(9):705–14.

Nakazato Y, Sugiyama T, Ohno R, Shimoyama H, Leung DL, Cohen AA, et al. Estimation of homeostatic dysregulation and frailty using biomarker variability: a principal component analysis of hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10314.

Noori N, Sharma Parpia A, Lakhani R, Janes S, Goldstein MB. Frailty and the quality of life in hemodialysis patients: the importance of waist circumference. J Renal Nutr. 2018;28(2):101–9.

Okuyama M, Takeuchi H, Uchida HA, Kakio Y, Okuyama Y, Umebayashi R, et al. Peripheral artery disease is associated with frailty in chronic hemodialysis patients. Vascular. 2018;26(4):425–31.

Orlandi FDS, Gesualdo GD. Assessment of the frailty level of elderly people with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis. Acta Paulista Enfermagem. 2014;27(1):29–34.

Painter P, Kuskowski M. A closer look at frailty in ESRD: getting the measure right. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2013;17(1):41–9.

Poveda V, Filgueiras M, Miranda V, Santos-Silva A, Paúl C, Costa E. Frailty in end-stage renal disease patients under dialysis and its association with clinical and biochemical markers. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6(2):103–6.

Schachter ME, Saunders MJ, Akbari A, Caryk JM, Bugeja A, Clark EG, et al. Technique survival and determinants of technique failure in in-center nocturnal hemodialysis: a retrospective observational study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120975305.

Soysal P, Isik AT, Buyukaydin B, Kazancioglu R. A comparison of end-stage renal disease and Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly through a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(8):1627–32.

Sy J, McCulloch CE, Johansen KL. Depressive symptoms, frailty, and mortality among dialysis patients. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2019;23(2):239–46.

Takeuchi H, Uchida HA, Kakio Y, Okuyama Y, Okuyama M, Umebayashi R, et al. The prevalence of frailty and its associated factors in Japanese hemodialysis patients. Aging Dis. 2018;9(2):192–207.

Usui N, Yokoyama M, Nakata J, Suzuki Y, Tsubaki A, Kojima S, et al. Association between social frailty as well as early physical dysfunction and exercise intolerance among older patients receiving hemodialysis. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(8):664–9.

van Loon IN, Goto NA, Boereboom FTJ, Bots ML, Verhaar MC, Hamaker ME. Frailty screening tools for elderly patients incident to dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(9):1480–8.

Yabuuchi J, Ueda S, Yamagishi SI, Nohara N, Nagasawa H, Wakabayashi K, et al. Association of advanced glycation end products with sarcopenia and frailty in chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17647.

Yadla M, John JP, Mummadi M. A study of clinical assessment of frailty in patients on maintenance hemodialysis supported by cashless government scheme. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2017;28(1):15–22.

Yao L, Yin L, Liu F. P1512 The relationship among anxiety, depression and frailty in maintenance hemodialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(Supplement_3):1512.

Young HML, March DS, Highton PJ, Graham-Brown MPM, Churchward DC, Grantham C, et al. Exercise for people living with frailty and receiving haemodialysis: a mixed-methods randomised controlled feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11): e041227.

Yuan H, Zhang Y, Xue G, Yang Y, Yu S, Fu P. Exploring psychosocial factors associated with frailty incidence among patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(9–10):1695–703.

Yun HJ, Ryoo SR, Kim JE, Choi YJ, Park I, Shin GT, et al. Trabecular bone score may indicate chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) phenotypes in hemodialysis patients: a prospective observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):299.

Zanotto T, Mercer TH, van der Linden ML, Rush R, Traynor JP, Petrie CJ, et al. The relative importance of frailty, physical and cardiovascular function as exercise-modifiable predictors of falls in haemodialysis patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):99.

Zanotto T, Mercer TH, van der Linden ML, Koufaki P. Screening tools to expedite assessment of frailty in people receiving haemodialysis: a diagnostic accuracy study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):411.

Brar RS, Whitlock R, Lerner B, Bohm C, Komenda P, Rigatto C, et al. The impact of frailty on technique failure and mortality in patients on home dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:975.

Schweitzer CD, Anagnostakos JP, Nagarsheth KH. Frailty as a predictor of adverse outcomes after peripheral vascular surgery in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am Surg. 2022;88(4):686–91.

Chan GCK, Ng JKC, Chow KM, Kwong VWK, Pang WF, Cheng PMS, et al. Interaction between central obesity and frailty on the clinical outcome of peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0241242 (no pagination).

Chan GCK, Ng JKC, Chow KM, Kwan BCH, Kwong VWK, Pang WF, et al. Depression does not predict clinical outcome of Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients after adjusting for the degree of frailty. BMC Nephrology. 2020;21(1):329.

Chan GCK, Ng JKC, Chow KM, Kwong VWK, Pang WF, Cheng PMS, et al. Progression in physical frailty in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2021;46(3):342–51.

Chan GCK, Ng JKC, Chow KM, Kwong VWK, Pang WF, Cheng PMS, et al. Impact of frailty and its inter-relationship with lean tissue wasting and malnutrition on kidney transplant waitlist candidacy and delisting. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(11):5620–9.

Farragher JF, Oliver MJ, Jain AK, Flanagan S, Koyle K, Jassal SV. PD assistance and relationship to co-existing geriatric syndromes in incident peritoneal dialysis therapy patients. Perit Dial Int. 2019;39(4):375–81.

Kamijo Y, Kanda E, Ishibashi Y, Yoshida M. Sarcopenia and frailty in PD: Impact on mortality, malnutrition, and inflammation. Perit Dial Int. 2018;38(6):447–54.

Ng JK, Kwan BC, Chow KM, Cheng PM, Law MC, Pang WF, et al. Frailty in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients: prevalence and prognostic significance. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2016;41(6):736–45.

Szeto CC, Chan GC, Ng JK, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Cheng PM, et al. Depression and physical frailty have additive effect on the nutritional status and clinical outcome of Chinese peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43(3):914–23.

Yi C, Lin J, Cao P, Chen J, Zhou T, Yang R, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of coexisting frailty and cognitive impairment in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Sci. 2018;8(1):17305.

Haugen CE, Thomas AG, Chu NM, Shaffer AA, Norman SP, Bingaman AW, et al. Prevalence of frailty among kidney transplant candidates and recipients in the United States: estimates from a national registry and multicenter cohort study. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2020;20(4):1170–80.

Haugen CE, Gross A, Chu NM, Norman SP, Brennan DC, Xue QL, et al. Development and validation of an inflammatory-frailty index for kidney transplantation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(3):470–7.

Cheng XS, Myers J, Han J, Stedman MR, Watford DJ, Lee J, et al. Physical performance testing in kidney transplant candidates at the top of the Waitlist. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(6):815–25.

Chu NM, Deng A, Ying H, Haugen CE, Garonzik Wang JM, Segev DL, et al. Dynamic frailty before kidney transplantation: time of measurement matters. Transplantation. 2019;103(8):1700–4.

Lorenz E, Cosio F, Bernard S, Bogard S, Bjerke B, Geissler E, et al. The relationship between frailty and decreased physical performance with death on the kidney transplant waiting list. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(Supplement 3):332.

Manay P, Ten Eyck P, Kalil R, Swee M, Sanders ML, Binns G, et al. Frailty measures can be used to predict the outcome of kidney transplant evaluation. Surgery (United States). 2021;169(3):686–93.

McAdams-Demarco MA, Law A, King E, Orandi B, Salter M, Gupta N, et al. Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(1):149–54.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, King EA, Luo X, Haugen C, DiBrito S, Shaffer A, et al. Frailty, length of stay, and mortality in kidney transplant recipients: a national registry and prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(6):1084–90.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Ying H, Thomas AG, Warsame F, Shaffer AA, Haugen CE, et al. Frailty, inflammatory markers, and Waitlist mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease in a prospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2018;102(10):1740–6.

Novais T, Pongan E, Gervais F, Coste MH, Morelon E, Krolak-Salmon P, et al. Pretransplant comprehensive geriatric assessment in older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron. 2021;145:692.

Perez Fernandez M, Martinez Miguel P, Ying H, Haugen CE, Chu NM, Rodriguez Puyol DM, et al. Comorbidity, frailty, and waitlist mortality among kidney transplant candidates of all ages. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(2):103–10.

Quint EE, Schopmeyer L, Banning LBD, Moers C, El Moumni M, Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke GJ, et al. Transitions in frailty state after kidney transplantation. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020;405(6):843–50.

Schopmeyer L, El Moumni M, Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke GJ, Berger SP, Bakker SJL, Pol RA. Frailty has a significant influence on postoperative complications after kidney transplantation-a prospective study on short-term outcomes. Transpl Int. 2019;32(1):66–74.

Shrestha P, Haugen CE, Chu NM, Shaffer A, Garonzik-Wang J, Norman SP, et al. Racial differences in inflammation and outcomes of aging among kidney transplant candidates. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):176.

Stedman MR, Watford DJ, Chertow GM, Tan JC. Karnofsky performance score-failure to thrive as a frailty proxy? Transpl Direct. 2021;7(7): e708.

Warsame F, Haugen CE, Ying H, Garonzik-Wang JM, Desai NM, Hall RK, et al. Limited health literacy and adverse outcomes among kidney transplant candidates. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2019;19(2):457–65.

Watford DJ, Cheng XS, Han J, Stedman MR, Chertow GM, Tan JC. Toward telemedicine-compatible physical functioning assessments in kidney transplant candidates. Clin Transplant. 2021;35(2): e14173.

dos Santos Mantovani M, de Carvalho NC, Archangelo TE, de Andrade LGM, Filho SPF, de Souza Cavalcante R, et al. Frailty predicts surgical complications after kidney transplantation. A propensity score matched study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0229531 (no pagination).

Garonzik-Wang JM, Govindan P, Grinnan JW, Liu M, Ali HM, Chakraborty A, et al. Frailty and delayed graft function in kidney transplant recipients. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill : 1960). 2012;147(2):190–3.

Konel JM, Warsame F, Ying H, Haugen CE, Mountford A, Chu NM, et al. Depressive symptoms, frailty, and adverse outcomes among kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transpl. 2018;32(10):e13391 (no pagination).

Kosoku A, Uchida J, Iwai T, Shimada H, Kabei K, Nishide S, et al. Frailty is associated with dialysis duration before transplantation in kidney transplant recipients: a Japanese single-center cross-sectional study. Int J Urol. 2020;27(5):408–14.

McAdams-Demarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, Chow E, Grams M, Walston J, et al. Frailty and early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(8):2091–5.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Isaacs K, Darko L, Salter ML, Gupta N, King EA, et al. Changes in frailty after kidney transplantation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2152–7.

McAdams-DeMarco M, Law A, King B, Walston J, Segev D. Frailty, immunosuppression tolerance, and outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2014;98(1):619.

McAdams-DeMarco M, Ying H, Olorundare I, King E, Segev D. Frailty in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2016;100(7 Supplement 1):S170.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Olorundare IO, Ying H, Warsame F, Haugen CE, Hall R, et al. Frailty and postkidney transplant health-related quality of life. Transplantation. 2018;102(2):291–9.

Nastasi AJ, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Schrack J, Ying H, Olorundare I, Warsame F, et al. Pre-kidney transplant lower extremity impairment and post-kidney transplant mortality. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(1):189–96.

Aline de Sousa M, Marcelo Aparecido B, Roberta Maria de Pina P, Rosalina Aparecida Partezani R, Jack Roberto Silva F, Luciana K. Frailty in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease under conservative treatment. Rev Rene. 2016;17(3):386–92.

Rodriguez Villarreal I, Ortega O, Hinostroza J, Cobo G, Gallar P, Mon C, et al. Geriatric assessment for therapeutic decision-making regarding renal replacement in elderly patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron - Clin Pract. 2014;128(1–2):73–8.

Delgado C, Grimes BA, Glidden DV, Shlipak M, Sarnak MJ, Johansen KL. Association of Frailty based on self-reported physical function with directly measured kidney function and mortality. BMC Nephrology. 2015;16(1):203 ((no pagination)).

Pyart R, Aggett J, Goodland A, Jones H, Prichard A, Pugh J, et al. Exploring the choices and outcomes of older patients with advanced kidney disease. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0234309 ((no pagination)).

Brar RS, Whitlock RH, Komenda PVJ, Rigatto C, Prasad B, Bohm C, et al. Provider perception of frailty is associated with dialysis decision making in patients with advanced ckd. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(4):552–9.

Haugen CE, Chu NM, Ying H, Warsame F, Holscher CM, Desai NM, et al. Frailty and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(4):576–82.

Kennard A, Glasgow N, Rainsford S, Talaulikar G. Frailty in advanced chronic kidney disease: Perceptions and practices among treating clinicians. Renal Soc Austral J. 2022;18(2):44–50.

Tarca B, Jesudason S, Bennett P, Ovenden M, Southwell P, Wycherley T, et al. Research involving people receiving peritoneal dialysis: Lessons learned. Renal Soc Austral J. 2022;18:51.

Lewis ET, Howard L, Cardona M, Radford K, Withall A, Howie A, et al. Frailty in Indigenous populations: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 785460.

Modderman RPO, Tonkin C, Zabeen S, Hughes J. Informing the evidence-practicegap about frailty detection measures among adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with advanced kidney disease: the live strong COVID-safe and frailty free after starting dialysis project. Nephrology. 2021;26:23–4.

Sternberg SA, Schwartz AW, Karunananthan S, Bergman H, Mark CA. The identification of frailty: a systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2129–38.

van AbellanKan G, Rolland Y, Bergman H, Morley JE, Kritchevsky SB, Vellas B. The I.A.N.A Task Force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(1):29–37.

Kao J, Reid N, Hubbard RE, Homes R, Hanjani LS, Pearson E, et al. Frailty and solid-organ transplant candidates: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):864.

Boyd CM, Xue QL, Simpson CF, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am J Med. 2005;118(11):1225–31.

Rosa PHd, Beuter M, Benetti ERR, Bruinsma JL, Venturini L, Backes C. Stressors factors experienced by hospitalized elderly from the perspective of the neuman systems model. Escola Anna Nery; 2018.

Basile G, Catalano A, Mandraffino G, Maltese G, Alibrandi A, Ciancio G, et al. Frailty modifications and prognostic impact in older patients admitted in acute care. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(1):151–5.

Cunha AIL, Veronese N, de Melo BS, Ricci NA. Frailty as a predictor of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;56: 100960.

Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, Chertow GM, Segal MR, Chiang J, et al. Factors associated with frailty and its trajectory among patients on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol : CJASN. 2017;12(7):1100–8.

Carvalho TCd, Valle APd, Jacinto AF, Mayoral VFdS, Boas PV. Impact of hospitalization on the functional capacity of the elderly: a cohort study. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia. 2018;21:134–42.

Dent E, Chapman I, Howell S, Piantadosi C, Visvanathan R. Frailty and functional decline indices predict poor outcomes in hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43(4):477–84.

Dent E, Hoogendijk EO. Psychosocial factors modify the association of frailty with adverse outcomes: a prospective study of hospitalised older people. BMC geriatr. 2014;14:108.

Evans SJ, Sayers M, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. The risk of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older patients in relation to a frailty index based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Age Ageing. 2014;43(1):127–32.

Irina G, Refaela C, Adi B, Avia D, Liron H, Chen A, et al. Low Blood ALT activity and high FRAIL questionnaire scores correlate with increased mortality and with each other. A prospective study in the internal medicine department. J Clin Med. 2018;7(11):386.

Joosten E, Demuynck M, Detroyer E, Milisen K. Prevalence of frailty and its ability to predict in hospital delirium, falls, and 6-month mortality in hospitalized older patients. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:1.

Pilotto A, Rengo F, Marchionni N, Sancarlo D, Fontana A, Panza F, et al. Comparing the prognostic accuracy for all-cause mortality of frailty instruments: a multicentre 1-year follow-up in hospitalized older patients. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1): e29090.

Ritt M, Bollheimer LC, Sieber CC, Gaßmann KG. Prediction of one-year mortality by five different frailty instruments: a comparative study in hospitalized geriatric patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:66–72.

Ritt M, Rádi KH, Schwarz C, Bollheimer LC, Sieber CC, Gaßmann KG. A comparison of frailty indexes based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment for the prediction of adverse outcomes. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(7):760–7.

Ritt M, Ritt JI, Sieber CC, Gaßmann KG. Comparing the predictive accuracy of frailty, comorbidity, and disability for mortality: a 1-year follow-up in patients hospitalized in geriatric wards. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:293–304.

Fairhall N, Kurrle SE, Sherrington C, Lord SR, Lockwood K, John B, et al. Effectiveness of a multifactorial intervention on preventing development of frailty in pre-frail older people: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5(2): e007091.

Chowdhury R, Peel NM, Krosch M, Hubbard RE. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;68:135–42.

Turner G, Clegg A. Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British geriatrics society, Age UK and royal college of general practitioners report. Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):744–7.

Society BG. Consensus best practice guidance for the care of older people living with frailty in community and outpatient settings. United Kingdom: British Geriatrics Society in Association with the Royal College of General Practitioners and Age; 2014.

Afilalo J, Lauck S, Kim DH, Lefèvre T, Piazza N, Lachapelle K, et al. Frailty in older adults undergoing aortic valve replacement: the FRAILTY-AVR study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):689–700.

Richter D, Guasti L, Walker D, Lambrinou E, Lionis C, Abreu A, et al. Frailty in cardiology: definition, assessment and clinical implications for general cardiology. A consensus document of the Council for Cardiology Practice (CCP), Association for Acute Cardio Vascular Care (ACVC), Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Council on Valvular Heart Diseases (VHD), Council on Hypertension (CHT), Council of Cardio-Oncology (CCO), Working Group (WG) Aorta and Peripheral Vascular Diseases, WG e-Cardiology, WG Thrombosis, of the European Society of Cardiology, European Primary Care Cardiology Society (EPCCS). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(1):216–27.

Ijaz N, Buta B, Xue QL, Mohess DT, Bushan A, Tran H, et al. Interventions for frailty among older adults with cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(5):482–503.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Ms Rosie Glynn from The Australian Capital Territory Health Library for her invaluable assistance with construction of the search strategy and citation searches.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK designed the search strategy, made substantial contributions to the concept and design of the article, data extraction and analysis and data interpretation manuscript, and provided approval for the final version for submission. Competing interests: no relevant disclosures. SR provided methodological guidance, made substantial contributions to abstract and title review, data extraction, analysis and data interpretation, provided draft revision and approval for the final version for submission. Competing interests: no relevant disclosures. NG provided methodological guidance, made substantial contributions to the concept and design of the article, data extraction, analysis and data interpretation, provided draft revision and approval for the final version for submission. Competing interests: no relevant disclosures. GT made substantial contributions to the concept and design of the article, data extraction, analysis and data interpretation and offered structural and content revision and approval for the final version for submission. Competing interests: no relevant disclosures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search Strategy.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Figure 1.

a. Prevalence of frailty based on assessment by Frailty Index in CKD populations. b. Prevalence of frailty based on assessment by Clinical Frailty Scale in CKD populations. c. Prevalence of frailty based on assessment by Clinical Frailty Scale in HD populations. d. Prevalence of frailty based on assessment by FRAIL scale in HD populations. e. Prevalence of frailty based on assessment by Frailty Index of HD populations. f. Prevalence of frailty based on assessment by Clinical Frailty Scale of PD populations.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 4.