Abstract

Background

Delirium is strongly associated with poor health outcomes, yet it is frequently underdiagnosed. Limited research on delirium has been conducted in Nursing Homes (NHs). Our aim is to assess delirium prevalence and its associated factors, in particular pharmacological prescription, in this care setting.

Methods

Data from the Italian “Delirium Day” 2016 Edition, a national multicenter point-prevalence study on patients aged 65 and older were analyzed to examine the associations between the prevalence of delirium and its subtypes with demographics and information about medical history and pharmacological treatment. Delirium was assessed using the Assessment test for delirium and cognitive impairment (4AT). Motor subtype was evaluated using the Delirium Motor Subtype Scale (DMSS).

Results

955 residents, from 32 Italian NHs with a mean age of 84.72 ± 7.78 years were included. According to the 4AT, delirium was present in 260 (27.2%) NHs residents, mainly hyperactive (35.4%) or mixed subtypes (20.7%). Antidepressant treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was associated with lower delirium prevalence in univariate and multivariate analyses.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of delirium in NHs highlights the need to systematically assess its occurrence in this care settings. The inverse association between SSRIs and delirium might imply a possible preventive role of this class of therapeutic agents against delirium in NHs, yet further studies are warranted to ascertain any causal relationship between SSRIs intake and reduced delirium incidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Delirium is a geriatric syndrome characterized by inattention and cognitive abnormalities. It has typically a sudden onset, fluctuating course and a multifactorial etiology [1]. The pathophysiology of delirium is complex and still not completely clarified, involving a predisposing cerebral vulnerability and various precipitating factors. Brain resilience is mainly lowered by neuronal loss, damaged microvasculature, decline in the normal antioxidant defense mechanisms, decreased number of acetylcholine producing neurons and abnormal microglial responsiveness to inflammatory stimuli [2]. In this context, stressful events can trigger several pathophysiological phenomena, such as oxygen or glucose deficiencies, neuroinflammation, damage of blood-brain barrier and/or neurotransmitter imbalance. Whatever the primary etiology, it is hypothesized that impaired neuronal network connectivity may be the ultimate event in delirium [3].

Due to the presence of multiple risk factors such as advanced age, low education, high prevalence of dementia, functional dependence, and malnutrition, Nursing Homes (NHs) residents are at high risk of developing delirium. Nevertheless, only few studies on this topic have been done in NHs, with heterogeneous results using different delirium assessment tools, reporting a prevalence ranging from 1.4 to 70.3% [4,5,6,7]. In our previous multicenter point-prevalence study, involving numerous hospital departments, long-term care facilities, and NHs throughout Italy, we observed a 36.8% prevalence of delirium in 1,454 older NHs residents [8]. Delirium is associated with poor clinical outcomes, such as decline in cognitive and functional status, increased morbidity and mortality and high health care costs. Despite this, delirium is often underdiagnosed [9, 10]. The diagnosis might even be more difficult in NHs, with an inverse correlation between the severity of patient’s frailty and the ability of healthcare professionals to recognize this syndrome [11]. One potential cause of underdiagnosis might be the lack of systematic use of diagnostic tools [12]. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is a widely used instrument to assess delirium [13]. However, a training is recommended for its optimal use, and the tool was designed to be scored based on observations made during formal cognitive assessment [14]. Moreover, there were no studies specifically addressing the performance of CAM in patients with different stages of dementia in whom diagnosis, especially in those with moderate-severe cognitive decline, can be particularly challenging [15]. The 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT) [16] was developed as a short delirium assessment tool intended for clinical use in general settings at first presentation and when delirium is suspected. Administration of 4AT does not require special training and can be performed by both nurses and physicians. Since publication, 4AT performance has been evaluated in multiple studies [17], and it is widely used for the identification of patients with delirium in different care setting, showing good sensitivity and specificity [18,19,20].

The aim of this study is to describe the prevalence of delirium in Italian NHs, to characterize delirium motor subtypes in all residents with delirium and to investigate the main associated factors, using data from the “Delirium Day” 2016, a large project involving different health care settings.

Different drug classes have been advocated to be associated with delirium. However, there is still no high quality evidence on the association of specific pharmacological categories and this geriatric syndrome and results where sometimes conflicting [21]. In view of the difficulty of carrying out randomized controlled studies on this topic, it’s important to investigate it using high quality observational data.

In this context, among potential contributors to delirium, we aimed at analyzing the association between delirium in NHs residents and pharmacological treatments shown to be associated with delirium in other settings.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Italian “Delirium Day”, 2016 edition, a national multicenter point-prevalence study. The aim and the details of the Delirium Day studies have been described elsewhere [22]. Briefly, the physicians belonging to 12 Italian scientific societies were invited to participate to the study. Data about patients older than 65 years and admitted to the participating centers were collected from 00:00 to 23:59 on the 28th of September 2016. Patients affected by aphasia, blindness, deafness or in critical conditions (coma or terminally ill) were excluded. The Delirium Day collected patient data from different settings, such as hospitals, rehabilitations, long term care and hospices but we only considered data of patients from NHs. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical standards. The Ethical Committee of the IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia, Rome (Prot CE/PROG.500) approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or from their next of kin when the participants were not capable of giving informed consent themselves because of delirium or severe cognitive impairment.

Data collection

On the index day, demographics and information about medical history as well as the total number of medications taken by each patient and the use of specific pharmacological classes were collected. Education was expressed in terms of years of study. Functional status was assessed using the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) [23]. It was recorded whether physical restraints, defined as vests, wrists, inguinal restraints and bedrail, were in use during evaluation. Nutritional status was evaluated on the index day and classified according to clinical judgment of the attending physician, as “well nourished,” “at risk of malnutrition,” or “malnourished”. Dementia was diagnosed if the patient had documented diagnosis in the medical record and/or was prescribed acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or memantine. The burden of multimorbidity was assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index [24]. Polypharmacy has been defined as the use of five or more different drugs.

Delirium assessment

The presence of Delirium was assessed with 4AT. The tool is based on 4 items investigating acute changes in alertness, attention (months of the year in backwards order starting from December) and cognition (age, date of birth, place and current year reporting). The likelihood of delirium is classified according to the final score as follows: absence of delirium (0 points), unlikely diagnosis (1–3 points) or probable diagnosis (4 + diagnosis) [16]. The delirium assessment was conducted by the usual staff (physicians or nurses) on duty on the reference day, who were involved in daily care of enrolled residents. The motor subtype of delirium was determined using the Delirium Motor Subtype Scale (DMSS) [25].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or as median ± interquartile range where appropriate, while categorical data are presented as counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were performed using the one-way ANOVA or t test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test or Mann-Whitney U test for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. The categorical variables were compared between groups using the χ2 test. Variables found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis or clinically meaningful ones were included in a multiple stepwise (backward) logistic regression model, adjusted by age and sex, in order to determine the factors independently associated with delirium. The level of significance was established as 95% (p < 0.05).

For the selected models a sensitivity analysis was performed to verify the impact of cluster structure of data. We fitted a random intercept model able to take into account the correlation among response within the same NH. Analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC),

Results

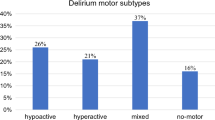

Overall, 32 NHs collected the study data on the index day. We evaluated 955 residents, 288 male and 667 female (69.8%). The mean age of the sample was 84.72 ± 7.78 years. Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. Based on the 4AT score, delirium was present in 260 (27.2%) NHs residents. According to the DMSS scores (available in 91.2% of residents), 35.4% of them had a hyperactive delirium, 13.5% hypoactive and 20.7% showed mixed symptoms, while 30.4% did not show motor features.

Factors associated with delirium at multivariate analysis (Table 2) were worst functional and nutritional status, dementia, antipsychotics treatment and the presence of physical restraints. Antidepressant treatment and higher education were associated with lower delirium prevalence. Exploring more in depth the association between psychotropic drugs and delirium, both typical and atypical antipsychotics were associated with higher prevalence of delirium while, among antidepressants, only selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) showed an inverse association with delirium at the univariate and multivariate analysis (Tables 1 and 3). There were no differences in the clinical characteristics, including prevalence of dementia, malnutrition and disability between residents treated with antidepressants and those who were not treated (see supplemental table, S1). Antidepressant and SSRIs confirmed their negative association with delirium in the sensitivity analysis (p-value 0.0077 and 0.0411, respectively).

Discussion

The Delirium Day 2016 study found that the prevalence of delirium in NHs residents is high with more than one fourth of patients identified as suffering from this condition. These prevalence data are lower than those reported in our previous publication investigating prevalence of delirium in Italian NHs [8], nevertheless confirming that this syndrome is very common in this care setting. The point prevalence design of the study, the different NHs involved and the lower dementia prevalence (52% vs. 44%) could, at least in part, justify such difference. Moreover, similar factors are associated with the presence of delirium, i.e. dementia, worst functional and nutritional status, antipsychotic treatment and physical restraints, while more years of education showed a protective effect.

Our prevalence data align with those from population with high dementia prevalence [26, 27]. The main associated factors like dementia, functional impairment, malnutrition, antipsychotic treatment, and physical restraints are well documented risk factors consistent with those reported in the literature [7] and better education might exert their protective effect on delirium being a marker of cognitive reserve [28, 29].

A main novelty of this study compared with our previous analysis [8], was the characterization of delirium motor subtype in more than 90% of residents with delirium. One third of the NHs residents had a hypoactive subtype of delirium or a mixed subtype, including hypoactive phases. Hypoactive delirium is subtle and more frequently goes undetected compared to the hyperactive form [30], with a worse prognostic value, at least in hospitalized patients [31,32,33,34]. In contrast with the hospital data [35], the most prevalent motor subtype was hyperactive delirium in NHs residents. This probably reflects the profound differences between these two populations in terms of clinical characteristics and treatments.

A new finding of this study was the inverse relation between antidepressants, specifically SSRIs, and delirium. In our previous work on delirium day in NHs we have found an inverse association between antidepressants and delirium, but only in the univariate analysis. Antidepressants have been previously associated with a higher risk of delirium, especially older antidepressants with high anticholinergic activity [36]. Aloisi G. et al. [37] found a positive association between the use of atypical antidepressants and delirium in a population of older adults admitted to an acute ward analyzing data from the 2015–2016 Delirium Day. Although second generation antidepressants could be associated with delirium, especially when concomitant side effect such as hyponatremia occur [38], a recent meta-analysis found no association between antidepressants and delirium [21]. On the other hand, no evidence is available for a protective effect of antidepressants for delirium particularly in NHs residents. In a secondary analysis of a large cohort of medical and surgical critically ill patients, Austin et al. [39] found that administration of an SSRIs was associated with decreased risk of delirium in the 24 h following wards admission.

Although our study design does not allow to establish a causality, there are different mechanisms by which SSRIs may exert a protective effect on delirium. SSRIs may have different anti-inflammatory properties [40]. They can reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines while increasing levels of anti-inflammatory Interleukin-10. They may reduce neurotoxicity influencing tryptophan kynurenine metabolic pathway, augmenting the ratio between neuroprotective and pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic metabolite. SSRIs can also modulate inflammation down-regulating Nuclear Factor kappa B signaling, inhibiting or reducing expression of inflammatory genes and mediators and reducing polymorphonuclear chemotaxis and T-cell proliferation. SSRIs may exert an anti-anxiety effect that could also be protective against the development of an episode of delirium [41]. Moreover, SSRIs may also protect against cognitive decline. In animal models’ citalopram has shown to improve cognitive behavior reducing amyloid beta levels and mitochondrial and synaptic toxicities suggesting a possible protective against mutant amyloid beta precursor protein and amyloid beta induced injuries in patients with depression, anxiety and Alzheimer’s disease [42]. A recent systematic review showed that some subgroups of patients, such as older subjects with depression or stroke, may benefit from long-term SSRIs treatment on memory performance [43].

Noteworthy, it should be underlined that analyzing the relationship between drugs and delirium is a complex issue. For example, a recent systematic review [21] found that the majority of prospective studies do not confirm antipsychotics as a direct risk factor for delirium. Their relationship could be due to confounding by indication, especially when analyzed in cross-sectional studies, as antipsychotics are often used empirically, although inappropriately, in the treatment of hyperactive delirium episodes. Even in the case of antidepressants the association might be non-causal, possibly due to a reduced rate of treatment of individuals with severe dementia, although a substantial number of patients with dementia are being prescribed antidepressants [44, 45].

The lack of association between polipharmacy and delirium might be unexpected. However, pharmacological treatments of NHs residents are mainly characterized by chronic therapies, while polypharmacy is likely to be associated with delirium when there are newly introduced drugs, in particular if they are inappropriate. Indeed, this result is in line with our previous work [8]. Moreover, it is noteworthy that a previous study, based on data from the 2015 and 2016 editions of the Delirium Day on hospitalized older patients, showed an association between polypharmacy and delirium only in surgical departments [37].

Our study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. The 4AT could partially overestimate the prevalence of delirium in subjects with dementia, in which the items exploring attention and cognition could be altered because of cognitive impairment, and it doesn’t allow to distinguish between behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and delirium. However, attention tasks in patients with dementia are relatively preserved until an advanced stage of the disease [46] and disorientation is more common in patients with delirium or delirium superimposed on dementia than in those with dementia without delirium [47]. Although scientific literature has not yet provided ideal tools for the recognition of delirium in patients with dementia, the 4AT is so far considered to be a method with good sensitivity and specificity for the detection of this pathological condition according to validation and comparative studies [20]. The observational cross-sectional design of study does not allow to draw definite conclusions about the causal relation between different associated factors and delirium. To exclude a confounding by severity (i.e. residents taking antidepressants being in better clinical conditions, and hence at lower risk of delirium, than residents not prescribed antidepressants) we compared the clinical characteristics, including prevalence of dementia, malnutrition and disability in residents treated or not with antidepressants and SSRIs, finding no difference. Given the multiple potential mechanisms linking SSRIs with delirium, this finding is very intriguing and should lead to new research investigating the pathophysiology and prevention of delirium. The lack of association between other antidepressants classes, such as SNRI, and delirium might be due to the low number of subject taking these drugs.

Our study has important strength, including the multicentric design, the large sample size, the use of a standardized evaluation of delirium using a validated tool and the inclusion of several demographic and clinical characteristics as well as drug treatments in the statistical analysis. Moreover the substantial overlap of results with our previous findings strongly reinforces the validity and generalizability of our data.

Conclusions

The present study confirms a high prevalence of delirium in NHs residents. In this care setting, delirium is often superimposed on dementia favoring higher rate of adverse outcomes [15, 45].

Hypoactive and mixed forms of delirium are frequent in this population and could compromise its recognition by health care personnel if not actively sought.

Therefore, systematically screening for delirium in NHs should be strongly recommended to promptly identify residents suffering from delirium as well as an increased research effort should be promoted to determine predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in this care setting and to identify strategies to prevent or treat it.

In this contest the finding of an inverse association between antidepressants use, especially SSRI, and delirium is novel and deserves further investigation with prospective studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (a.cherubini@inrca.it).

Abbreviations

- NHs:

-

Nursing Homes

- CAM:

-

Confusion Assessment Method

- 4AT:

-

4 ‘A’s Test

- DMSS:

-

Delirium Motor Subtype Scale

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- SSRIs:

-

serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- SNRIs:

-

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

References

Fedecostante M, Cherubini A. Frailty and delirium: unveiling the hidden vulnerability of older hospitalized patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;70(October):16–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2019.10.020.

Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C, Shehabi Y, Girard TD, MacLullich AMJ, Slooter AJC, Ely EW, Delirium. NatRevDisPrimers.2020;6(1):90.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00223-4.Erratumin:NatRevDisPrimers.2020;6(1):94.PMID:33184265;PMCID:PMC9012267.

Maldonado JR. Delirium pathophysiology: an updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:1428–57.

De Lange E, Verhaak PFM, Van Der Meer K. Prevalence, presentation and prognosis of delirium in older people in the population, at home and in long term care: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(2):127–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3814.

Cheung ENM, Benjamin S, Heckman G, Ho JMW, Lee L, Sinha SK, Costa AP. Clinical characteristics associated with the onset of delirium among long-term nursing home residents. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0733-3.

Sabbe K, van der Mast R, Dilles T, Van Rompaey B. The prevalence of delirium in belgian nursing homes: a cross-sectional evaluation. BMC Geriatr. 2021;6;21(1):634. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02517-y. Erratum in: BMC Geriatr. 2021:1;21(1):673. PMID: 34742251; PMCID: PMC8571852.

Komici K, Guerra G, Addona F, Fantini C. Delirium in nursing home residents: a narrative review. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10(8):1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081544. PMID: 36011202; PMCID: PMC9407867.

Morichi V, Fedecostante M, Morandi A, Di Santo SG, Mazzone A, Mossello E, Bo M, Bianchetti A, Rozzini R, Zanetti E, Musicco M, Ferrari A, Ferrara N, Trabucchi M, Cherubini A, Bellelli G. A point prevalence study of Delirium in Italian nursing homes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2018;46(1–2):27–41. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490722.

Rice KL, Bennett M, Gomez M, Theall KP, Knight M, Foreman MD. Nurses’ recognition of delirium in the hospitalized older adult. Clin Nurse Spec. 2011;25(6):299–311. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0b013e318234897b. PMID:22016018.

Voyer P, Richard S, Doucet L, et al. Detection of delirium by nurses among long-term care residents with dementia. BMC Nurs. 2008;7:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-7-4.

Geriatric Medicine Research Collaborative. Increasing frailty is associated with higher prevalence and reduced recognition of delirium in older hospitalised inpatients: results of a multi-centre study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(2):325–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-022-00737-y. Epub 2023 Jan 25. PMID: 36696045; PMCID: PMC10113325.

Bellelli G, Nobili A, Annoni G, Morandi A, Djade CD, Meagher DJ, Maclullich AM, Davis D, Mazzone A, Tettamanti M, Mannucci PM. REPOSI (REgistro POliterapie SIMI) investigators. Under-detection of delirium and impact of neurocognitive deficits on in-hospital mortality among acute geriatric and medical wards. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(9):696–704.

Inouye SK, Van Dyck CH, Alessi CA. Clarifying confusion: the confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:941–8.

Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x. Epub 2008 Apr 1. PMID: 18384586; PMCID: PMC2585541.

Morandi A, Grossi E, Lucchi E, Zambon A, Faraci B, Severgnini J, MacLullich A, Smith H, Pandharipande P, Rizzini A, Galeazzi M, Massariello F, Corradi S, Raccichini A, Scrimieri A, Morichi V, Gentile S, Lucchini F, Pecorella L, Mossello E, Cherubini A, Bellelli G. The 4-DSD: a New Tool to assess Delirium superimposed on moderate to severe dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(7):1535–e15423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.02.029.

Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DH, Mazzola P, Turco R, Gentile S, Ryan T, Cash H, Guerini F, Torpilliesi T, Del Santo F, Trabucchi M, Annoni G, MacLullich AM. Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43:496–502.

Shenkin SD, Fox C, Godfrey M, Siddiqi N, Goodacre S, Young J, Anand A, Gray A, Hanley J, MacRaild A, Steven J, Black PL, Tieges Z, Boyd J, Stephen J, Weir CJ, MacLullich AMJ. Delirium detection in older acute medical inpatients: a multicentre prospective comparative diagnostic test accuracy study of the 4AT and the confusion assessment method. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1367-9.

Jeong E, Park J, Lee J. Diagnostic test accuracy of the 4AT for Delirium detection: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207515. PMID: 33076557; PMCID: PMC7602716.

Evensen S, Hylen Ranhoff A, Lydersen S, Saltvedt I. The delirium screening tool 4AT in routine clinical practice: prediction of mortality, sensitivity and specificity. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(4):793–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-021-00489-1. Epub 2021 Apr 4. PMID: 33813725; PMCID: PMC8321971.

Tieges Z, Maclullich AMJ, Anand A, Brookes C, Cassarino M, O’connor M, Ryan D, Saller T, Arora RC, Chang Y, Agarwal K, Taffet G, Quinn T, Shenkin SD, Galvin R. Diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT for delirium detection in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2021;50(3):733–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa224.

Reisinger M, Reininghaus EZ, Biasi J, Fellendorf FT, Schoberer D. Delirium-associated medication in people at risk: a systematic update review, meta-analyses, and GRADE-profiles. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2023;147(1):16–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13505. Epub 2022 Oct 11. PMID: 36168988; PMCID: PMC10092229.

Morandi A, Di Santo SG, Zambon A, Mazzone A, Cherubini A, Mossello E, Bo M, Marengoni A, Bianchetti A, Cappa S, Fimognari F, Incalzi RA, Gareri P, Perticone F, Campanini M, Penco I, Montorsi M, Di Bari M, Trabucchi M, Bellelli G. Delirium, dementia, and in-hospital mortality: the results from the Italian Delirium Day 2016, a national multicenter study. Journals Gerontol - Ser Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(6):910–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly154.

Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–8.

Meagher DJ, Moran M, Raju B, Gibbons D, Donnelly S, Saunders J, Trzepacz PT. Motor symptoms in 100 patients with delirium versus control subjects: comparison of subtyping methods. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:300–83.

McCusker J, Cole MG, Voyer P, Monette J, Champoux N, Ciampi A, Vu M, Belzile E. Prevalence and incidence of delirium in long-term care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1152–61.

Voyer P, Richard S, Doucet L, Cyr N, Carmichael PH. Examination of the multifactorial model of delirium among long-term care residents with dementia. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31:105–14.

Ormseth CH, LaHue SC, Oldham MA, Josephson SA, Whitaker E, Douglas VC. Predisposing and precipitating factors Associated with Delirium: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2249950. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49950. PMID: 36607634; PMCID: PMC9856673.

Richard N. Does Educational Attainment Contribute to Risk for Delirium? A potential role for Cognitive Reserve, the journals of Gerontology: Series A, 61, issue 12, December 2006,Pages1307–11,https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.12.1307

Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM Jr. Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467–73.

Avelino-Silva TJ, Campora F, Curiati JAE, Jacob-Filho W. Prognostic effects of delirium motor subtypes in hospitalized older adults: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191092. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191092. PMID: 29381733; PMCID: PMC5790217.

Trevisan C, Grande G, Rebora P, Zucchelli A, Valsecchi MG, Focà E, Ecarnot F, Marengoni A, Bellelli G. Early Onset Delirium during hospitalization increases In-Hospital and Postdischarge Mortality in COVID-19 patients: a Multicenter prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023;84(5):22m14565. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.22m14565. PMID: 37616485.

Bellelli G, Carnevali L, Corsi M, Morandi A, Zambon A, Mazzola P, Galeazzi M, Bonfanti A, Massariello F, Szabo H, Oliveri G, Haas J, d’Oro LC, Annoni G. The impact of psychomotor subtypes and duration of delirium on 6-month mortality in hip-fractured elderly patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4914. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 29851194.

Bellelli G, Speciale S, Barisione E, Trabucchi M. Delirium subtypes and 1-year mortality among elderly patients discharged from a post-acute rehabilitation facility. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007:62(10):1182-3. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/62.10.1182. PMID: 17921434.

Bellelli G, Morandi A, Di Santo SG, et al. Delirium Day: a nationwide point prevalence study of delirium in older hospitalized patients using an easy standardized diagnostic tool. BMC Med. 2016;14:106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0649-8.

Karlsson I. Drugs that induce delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(5):412-5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000017180.PMID:10473949.

Aloisi G, Marengoni A, Morandi A, Zucchelli A, Cherubini A, Mossello E, Bo M, Di Santo SG, Mazzone A, Trabucchi M, Cappa S, Fimognari FL, Incalzi RA, Gareri P, Perticone F, Campanini M, Montorsi M, Latronico N, Zambon A, Bellelli G, Italian Study Group on Delirium (ISGoD). Drug prescription and delirium in older inpatients: results from the Nationwide Multicenter Italian Delirium Day 2015–2016. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(2):18m12430. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18m12430. PMID: 30901165.

Gandhi S, Shariff SZ, Al-Jaishi A, Reiss JP, Mamdani MM, Hackam DG, Li L, McArthur E, Weir MA, Garg AX. Second-generation antidepressants and Hyponatremia Risk: a Population-based cohort study of older adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(1):87–96. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.08.020. Epub 2016 Oct 20. PMID: 27773479.

Austin CA, Yi J, Lin FC, Pandharipande P, Ely EW, Busby-Whitehead J, Carson SS. The Association of Selective Serotonin Reuptake inhibitors with delirium in critically ill adults: a secondary analysis of the bringing to light the risk factors and incidence of neuropsychologic dysfunction in ICU survivors ICU study. Crit Care Explor. 2022;4(7):e0740. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000740. PMID: 35923593; PMCID: PMC9329078.

Patel S, Keating BA, Dale RC. Anti-inflammatory properties of commonly used psychiatric drugs. Front Neurosci. 2023;16:1039379. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1039379. PMID: 36704001; PMCID: PMC9871790.

Arubala P. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram ameliorates cognitive decline and protects against amyloid beta-induced mitochondrial dynamics, biogenesis, autophagy, mitophagy and synaptic toxicities in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30(9):789–810. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddab091.

Schulkens JE, Deckers K, Jenniskens M, Blokland A, Verhey FR, Sobczak S. The effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on memory functioning in older adults: a systematic literature review. J Psychopharmacol. 2022;36(5):578–93. Epub 2022 Apr 29. PMID: 35486412; PMCID: PMC9112622.

Martinez C, Jones RW, Rietbrock S. Trends in the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias including those treated with antidementia drugs in the community in the UK: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e002080. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002080.

Drummond N, McCleary L, Freiheit E, Molnar F, Dalziel W, Cohen C, Turner D, Miyagishima R, Silvius J. Antidepressant and antipsychotic prescribing in primary care for people with dementia. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(11):e488–97. PMID: 30429194; PMCID: PMC6234938.

Bellelli G, Ornago AM, Cherubini A. Delirium in long-term care and the myth of Proteus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2024 Jan 23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18780. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38258608.

Morandi A, Davis D, Bellelli G, Arora RC, Caplan GA, Kamholz B, Kolanowski A, Fick DM, Kreisel S, MacLullich A, Meagher D, Neufeld K, Pandharipande PP, Richardson S, Slooter AJ, Taylor JP, Thomas C, Tieges Z, Teodorczuk A, Voyer P, Rudolph JL. The diagnosis of delirium superimposed on dementia: an emerging challenge. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:12–8.

Meagher DJ, Leonard M, Donnelly S, Conroy M, Saunders J, Trzepacz PT. A comparison of neuropsychiatric and cognitive profiles in delirium, dementia, comorbid delirium-dementia and cognitively intact controls. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(8):876–81. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.200956. Epub 2010 Jun 28. PMID: 20587481.

Funding

This article was co-funded by Next Generation EU - “Age-It - Ageing well in an ageing society” project (PE0000015), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) - PE8 - Mission 4, C2, Intervention 1.3”. The views and opinions expressed are only those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them. This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente to IRCCS INRCA and Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri IRCCS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the work: AC; FM. Data analysis: FM, AZ. Interpretation of the results: all authors.Drafting the article: BP; FM. Critical revision of the manuscript: all authors. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the participating centers and informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardian.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fedecostante, M., Balietti, P., Di Santo, S.G. et al. Delirium in nursing home residents: is there a role of antidepressants? A cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr 24, 767 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05360-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05360-z