Abstract

Objective

To explore the prevalence and potential influencing factors of social frailty among community-dwelling older adults from a global perspective.

Methods

Systematic searches were conducted on multiple databases including CNKI, VIP, Wanfang Data, CBM, Pubmed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Embase from inception to January 9, 2024. Two researchers performed a thorough literature search, gathered data, and independently evaluated the quality of the articles.

Results

2,426 literatures were examined, 45 were found to meet the specified criteria for inclusion, encompassing 314,454 participants. The combined prevalence of social pre-frailty and social frailty among community-dwelling older adults were found to be 34.5% and 21.1%, respectively. Depression, activities of daily living (ADL), physical inactivity, motor deficits, cognitive impairment, and physical frailty are potential risk factors.

Conclusions

Social pre-frailty and social frailty are frequent challenges faced by older adults living in the community. The prevalence of these conditions has been on the rise in recent years, underscoring the importance of implementing effective interventions. Early identification and intervention for individuals at risk of social frailty are essential for promoting healthy and active aging globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United Nations World Population Prospects points out that population aging is a major global trend. In the modern era, the challenges of a decline in the birth rate and aging societies in different nations have gained attention. It is estimated that by 2050, there will be more than 1.5 billion people aged 65 and over around the world [1]. As we grow older, our physical health and functional capacities naturally decrease. Hence, giving priority to the well-being of elderly individuals is a crucial component of healthcare that can enhance their quality of life and foster a healthy, active aging process.

Frailty is a condition associated with aging in which physiological reserves decrease [2]. Studies have shown that frailty is linked to a higher likelihood of experiencing falls, being hospitalized, developing disabilities, and even facing mortality [3]. Assessing the health of older adults has emerged as a crucial metric, garnering global recognition and interest from nations worldwide. Social frailty is a concept that refers to the lack or loss of social resources, behaviors, activities, and self-management skills needed to fulfill fundamental social needs [4]. According to the social production theory, these social needs include emotional needs, the need for behavior to be recognized, and the need for identity roles to be recognized [4]. This condition can occur at any stage of life and can have a significant impact on an individual’s overall well-being and quality of life [5]. Although frailty and social frailty are distinct concepts, they often and increasingly coexist [6]. Moreover, similar to frailty, the incidence of social frailty is on the rise and is closely linked to various negative consequences, such as physical impairment, cognitive decline, mood disorders, and even death [7].

Understanding the worldwide prevalence of social frailty can help policymakers evaluate the scope and severity of the problem, support continuous monitoring of at-risk populations, and direct clinical research efforts and public health surveillance. Some studies have examined social frailty among older adults living in the community, but the results are limited to specific countries. Although a meta-analysis [8] indicated that approximately 14.9 − 22.7% of older adults residing in community experience social frailty, the analysis merely offered a basic overview without delving into detailed quantitative assessments of prevalence and risk factors within the community demographic.

Therefore, we conducted this study to update the latest evidence on the prevalence and potential influencing factors of social frailty among older people in communities worldwide. This approach aims to offer healthcare experts with a broader scope of data, as well as furnish evidence-based backing for the formulation of pertinent health and social service protocols.

Methods

The study protocol had been registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022323690) and was conducted following PRISMA [9] and MOOSE [10] guidelines.

Search strategies

Systematic searches were conducted at CNKI, VIP, Wanfang Data, CBM, Pubmed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Embase from the establishment of the database to January 9, 2024. The search was confined to both the Chinese and English languages. Additionally, a thorough manual examination of the sources obtained in the studies was carried out to guarantee comprehensiveness of the search. Details of the search strategy were as follows: (aged OR elder* OR older*) AND (social frailty OR social vulnerability OR frailty OR pre-frail* OR frailty syndrome).

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria: (a) study design included cross-sectional or cohort studies; (b) participants were older adults living in communities, aged ≥ 60 years old; (c) outcome indicators were the prevalence and potential influencing factors of social frailty; (d) diagnostic criteria: diagnosis of social frailty had to be made using social frailty diagnostic tools such as: Makizako social Frailty Index (MSFI)、Help、participation、loneliness、financial、talk scale (HALEFT)、Tilbury Frailty Indicator (TFI)、Social Frailty Index (SFI)、Social frailty screening questionnaire (SFSQ)、Social frailty questionnaire (SFQ)、Social vulnerability index (SVI)、Lubben social network scale (LSNS-6 ) and Bunt; and (e) relevant studies were included regardless of the quality of the literature.

Exclusion criteria: (a) literature type of review, conference paper or abstract; (b) duplicate publications; (c) literature for which full text or required data were not available.

Study selection

Two researchers (L.J and Z.L.F) conducted the screening process of the studies independently. When two researchers had different opinions, the third researcher (Y.Y.J) was asked. Initially, duplicates were eliminated, then titles and abstracts were reviewed to exclude clearly irrelevant literature. Afterwards, the entire texts underwent examination, and the ultimate incorporation of literature was established according to inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were addressed through discourse and mediation with a third researcher. The data sheet with standard formatting contained the subsequent information: study author, publication year, country/region, mean age, study type, sample size, prevalence and factors influencing social frailty/pre-social frailty, and assessment tool.

Quality assessment

Two researchers (L.J and Z.L.F) assessed the quality of included studies using Agency for Healthcare and Research and Quality tool (AHRQ) [11] and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [12]. When two researchers had different opinions, the third researcher (Y.Y.J) was asked. AHRQ is used to assess the quality of the cross-sectional studies. The scale consists of 11 items with responses categorized as ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘unclear’. Each ‘yes’ response is counted as 1, while ‘no’ or ‘unclear’ responses are counted as 0. The total score is calculated by summing the scores of each item, ranging from 0 to 11. NOS is used to assess the quality of the cohort studies. The scale consists of 8 items with a maximum score of 9. Each study is classified as poor, fair, or good quality.

Statistical analysis

The research aimed to analyze the pooled prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of social frailty in older adults living in the communities. Furthermore, factors linked to social frailty were evaluated by computing the collective odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% CIs. Heterogeneity testing was performed using Stata 17.0 software. If the heterogeneity test I2 was less than 50%, it was considered as moderate or low heterogeneity, and the analysis was performed using a fixed-effects model. If I2 was 50% or higher, a random-effects model was used. The significance level for the Meta-analysis was set at α = 0.05. To address any noticeable clinical heterogeneity, we utilized methods such as subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, or descriptive analysis. Sensitivity analysis involved systematically excluding individual studies one by one. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plots and Egger’s test.

Results

Study selection

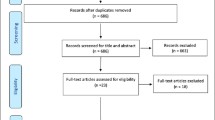

In our study, a total of 2426 studies were searched, with contributions from CNKI (n = 117), VIP (n = 73), Wanfang (n = 47), CBM (n = 53), Pubmed (n = 700), WOS (n = 588), Embase (n = 400), and Cochrane Library (n = 448). Among these, 473 studies were found to be duplicates, 1855 were excluded based on title and abstract screening, 98 underwent full-text reading rescreening, and ultimately 45 studies were included in the Meta-analysis. Figure 1. Flow diagram of study selection.

Study characteristics

45 studies were included, and Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these studies. These studies were published between 2015 and 2023, encompassing 314,454 participants from eight different countries. All study sites were community-based, comprising 34 cross-sectional studies and 11 cohort studies. Sample sizes varied from 103 to 222,179 individuals. Various assessments were utilized across studies to diagnose social frailty, including MSFI, HALFT, TFI, SFI, SFSQ, SFQ-9, SFQ-6, SVI, LSNS-6, and Bunt. The most frequently employed tool for assessing social frailty was the MSFI, utilized in 22 of the studies.

Methodological quality

Table 1 presents the results of the methodological quality assessment for all 45 studies in this systematic evaluation. In cross-sectional studies, 19 studies were categorized as low risk of bias and 17 studies were categorized as moderate risk of bias. In cohort studies, 5 studies were categorized as low risk of bias and 4 studies were categorized as moderate risk of bias. The most common cause of risk of bias were the failure to report non-response rates and the number and cause of missing data.

Prevalence of social frailty and social pre-frailty

A total of 45 studies, involving 314,454 individuals, were included in the meta-analysis on the prevalence of social frailty. The prevalence of social frailty varied from 3.5 to 71.1% among the studies. According to the random-effects model, the combined prevalence of social frailty in older adults living in the community was calculated to be 21.1% (95% CI = 17.8–24.5%). Considerable heterogeneity was noted among the 45 studies included in the analysis (I2 = 99.7%, Q = 15583.9, P < 0.001). Among these, 23 studies provided estimates of the prevalence of social pre-frailty in older adults living in the community, with prevalence rates ranging from 20.4 to 60.7%. The random-effects model revealed a combined prevalence of social pre-frailty in community-dwelling older adults at 34.5% (95% CI = 30.9–38.0%). A significant level of heterogeneity between studies was evident (I2 = 98.7%, Q = 1589.82, P < 0.001).

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis

To explore the heterogeneity among studies, we conducted subgroup analyses based on study design, sample size, region, country, time of publication, and diagnostic criteria for social decline.Table 2 demonstrates the specific results of the subgroup analysis In addition, we performed meta-regression analysis.The details are shown in Table 3.

For the meta-regression analyses, associations between prevalence of frailty and study characteristics including study design, sample size, region, country, publication time, and diagnostic criteria for social frailty were assessed by univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses. In the multivariate meta-regression model, country (β= -0.14, 95% CI = -0.27- -0.16, P = 0.02), and time to publication (β= -0.11, 95% CI = -0.19-0.02, P = 0.02) were associated with prevalence of social frailty. The remaining factors were not significantly associated with the prevalence of social debility.

Risk factors associated with social frailty

There were 8 studies reporting on depression, 4 on difficulties in ADLs, 4 on physical inactivity, 3 on motor dysfunction, 2 on cognitive functioning, and 2 on physical frailty.Meta-analysis results showed that depression, difficulties in ADLs, physical inactivity, motor dysfunction, cognitive deficits, and physical frailty were the risk factors for social frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Specific results are shown in Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis and publication of bias

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding individual studies one by one, revealing that the combined prevalence of social frailty ranged from 17.8 to 24.5%. This range was found to be not significantly different from the overall prevalence results, indicating the stability of the meta-analysis findings. The funnel diagram of prevalence studies on social debility showed no significant asymmetry. Additionally, the results of Egger’s test (P = 0.138) suggest a low probability of publication bias.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Although the prevalence of social frailty is relatively high, consensus on how to define and measure it is insufficient [58]. Social frailty is defined as a continuum of being at risk of losing, or having lost, resources that are important for fulfilling one or more basic social needs during one’s life span [4].

Our study is the first to systematically examine the prevalence and influencing factors of social frailty in community-dwelling older adults, revealing unique and significant findings. Our meta-analysis introduced the prevalence of social frailty in this population(21.1%) for the first time, showing that social frailty is more prevalent than physical frailty (10.7%, 95%CI: 10.5-10.9%) [59] and cognitive frailty (9%, 95% CI: 8-11%) [60] globally. This highlights the importance of addressing social factors associated with frailty in older adults to improve social participation, sense of belonging, and promote active and healthy aging as society and economy evolve. More interestingly, we also found that the pooled prevalence of pre-social frailty in community-dwelling older adults (34.5%) was much higher than the pooled prevalence of social frailty. It indicates that pre-social frailty is a larger population base than social frailty. This finding suggests that screening and interventions for community-dwelling older adults with pre-social frailty may provide an opportunity for effective management of social frailty and improved health outcomes.

Among the included studies, we found a high degree of heterogeneity. To explore the sources of this heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses to assess the characteristics of the included studies. Our analyses found that the pooled prevalence of the prevalence of social frailty among community-dwelling older adults based on cross-sectional study designs differed significantly from the pooled prevalence based on cohort study designs, suggesting that study design and sample size affect the pooled prevalence results and may be a source of heterogeneity. The occurrence of such differences can be explained by the fact that 14 of the 34 cross-sectional studies and 1 of the 11 cohort studies we included had sample sizes < 500, which may have led to less accurate results. For studies with a sample size of more than 500, 6 cross-sectional studies out of 11 reported a prevalence of 40% or more of social decline in community-dwelling older adults, which may explain the higher pooled prevalence in cross-sectional studies than in cohort studies.Zhang et al.’ study also supported the same conclusion [8].

Out of the 45 studies reviewed, 40 focused on surveys of older individuals in Asia, representing 96.8% of the total population. The majority of these studies were conducted in China, Japan, and South Korea, reflecting the significant size of aging population in these countries due to factors such as super-aging, low birth rates, and increasing rates of living alone. It has been reported that the Asia Pacific population is ageing faster than any other region in the world, accounting for 60% of the global population in 2022 and an estimated 55% by the year 2050 [61]. It is projected that the number of older adults in Asia Pacific who are aged 60 and over will rise from 549 million in 2017 to around 1.3 billion by the year 2050 [61]. This increased number of older adults may lead to the prevalence of frailty status, growing burdens on society, and various health outcomes [62]. Consequently, the prevalence findings derived from this collective analysis are more likely to reflect the prevalence of social vulnerability among older adults living in communities in Asia compared to other regions, influenced by factors such as geographical location, economic status, and cultural diversity. This highlights the need for future research to explore the epidemiology and causes of social vulnerability among older adults in non-Asian regions to establish consistent criteria for assessing social frailty and gain a more comprehensive understanding of its global prevalence.

Various assessment tools have been developed for social frailty due to the lack of a standardized concept. This systematic review focused on 11 assessment tools for social frailty in older adults, with the most commonly used being the MSFI, identified in 23 studies with a pooled prevalence of 23%. Following closely was the HALFT scale, utilized in 8 studies with a pooled prevalence of 19%. Upon further analysis, it was noted that 14 out of the 23 studies employing the MSFI scale were conducted in Japan. Given Japan’s status as the country with the highest proportion of older adults globally, this may explain the higher prevalence of social frailty detected by the MSFI scale in these studies.

According to the results of the time-stratified analysis, we found that the prevalence of social frailty increased year by year. The prevalence of frailty was 15% range 2015 from 2019 to 27% range 2020 from 2023. From 2015 to 2019, there were only 17 studies involving 42,364 participants, compared to 28 studies involving 272,090 participants from 2020 to 2023. An increase in sample size and a better understanding of the concept of social frailty may explain the higher combined prevalence estimates for 2020 to 2023. In addition, another reason for this trend may be related to the COVID-19 outbreak in 2019 [58]. In the context of major public health events, the older adults’s social activities with the outside world are reduced, the behavior of staying at home and sitting down is increased, and the older people are unable to skillfully use social software and cut off communication with the outside world, which may increase the occurrence of social weakness.

In terms of risk factors for social frailty in older people in the community, depression was found to be significantly associated with social frailty, which is consistent with previous findings [63]. This may be due to the older adults with depressed mood lose interest in life, avoid social behavior, resulting in a decline in social participation. Difficulties in ADLs, physical inactivity and motor dysfunction are risk factors for social frailty. When the older adults have impaired motor function, it will lead to low ADL ability of the older adults, and the number of physical activities will be reduced, and regular physical activities will help slow down the process of physical weakness of the older adults. Studies [64] have pointed to regular exercise as the preferred method for boosting self-efficacy, self-esteem and awareness of body intention. When the number of physical activities is reduced, the discomfort of physical function, psychological emotion and interpersonal communication in the older adults is enhanced, and the risk of social frailty is increased. Therefore, community workers should pay attention to outdoor activities for the older adults, such as community collective activities and participation in regional activities to promote physical improvement.

The study also showed that older adults with cognitive deficits had a 1.67-fold increased risk of social frailty. Previous studies have also shown a clear correlation between cognitive decline and low social participation in later life [65]. The possible mechanism is that the social pressure causes the disorder of multiple system organs in the body, and finally affects the cognitive function [66]. Therefore, taking measures to prevent cognitive decline in the older adults will help prevent or delay the occurrence of social frailty. This study also shows that social frailty is closely related to physical frailty. Nagai et al.’ study also supported the same conclusion [67]. Previous studies have demonstrated that social frailty in older adults can precede and lead to physical frailty, is associated with multiple adverse health outcomes, and is predictive of death [68]. Therefore, it is of great significance to evaluate and intervene the social aspects of senile frailty.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered.First, papers that were not written in Chinese or English were excluded due to lack of resources, which may cause language bias. Second, gray literature was not searched in this study, which may affect the results of Meta-analysis. Third, there was significant heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of prevalence.We found that country and publication time could explain some of the differences. In addition, sensitivity analysis and Egger’s test showed the reliability and low publication bias of our study. Finally, the 45 studies included in this study used different diagnostic criteria for social debility, which may have led to a slight bias between the preliminary findings.

Conclusion

This systematic review showed that prevalence of pre-social frailty and social frailty is common among older adults living in community-based settings and that there are more factors influencing it. In addition, the prevalence of social frailty has continued to increase in recent years. In the context of healthy aging, social frailty in community-dwelling older adults deserves widespread attention by health care workers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in CNKI, VIP, Wanfang Data, CBM, Pubmed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Embase.

References

Zarocostas J. The UN reports global asymmetries in population growth. Lancet. 2022;400(10347):148.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1365–75.

Bunt S, Steverink N, Olthof J, van der Schans CP, Hobbelen JSM. Social Frailty in older adults: a scoping review. Eur J Ageing. 2017;14(3):323–34.

Andrew MK. Frailty and Social Vulnerability. Interdisciplinary Top Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;41:186–95.

Hanlon P, Wightman H, Politis M, Kirkpatrick S, Jones C, Andrew MK, Vetrano DL, Dent E, Hoogendijk EO. The relationship between frailty and social vulnerability: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024;5(3):e214–26.

Goto T, Kishimoto T, Fujiwara S, Shirayama Y, Ichikawa T. Social Frailty as a predictor of all-cause mortality and functional disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):3410.

Zhang XM, Cao S, Gao M, Xiao S, Xie X, Wu X. The prevalence of Social Frailty among older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023;24(1):29–e3729.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Saltzman C. New FAI guidelines: STROBE, MOOSE, PRISMA, CONSORT. Foot Ankle Int. 2022;43(1):1.

Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C, Sampson M, Zhang L, Yazdi F, Mamaladze V et al. Celiac disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2004(104):1–6.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Makizako H, Shimada H, Tsutsumimoto K, Lee S, Doi T, Nakakubo S, Hotta R, Suzuki T. Social Frailty in Community-Dwelling older adults as a risk factor for disability. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(11):e10031007–1011.

Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, Makizako H, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, Makino K, Suzuki T, Shimada H. Association of Social Frailty with both cognitive and physical deficits among older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(7):603–7.

Ma L, Sun F, Tang Z. Social Frailty is Associated with Physical Functioning, Cognition, and Depression, and predicts mortality. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(8):989–95.

Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, Makino K, Lee S. Social Frailty leads to the development of physical Frailty among physically non-frail adults: a Four-Year Follow-Up longitudinal cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(3):1660–4601.

Rietman ML. a DL, van Oostrom SH, Picavet HSJ, Dollé MET, van Steeg H, Verschuren WMM, Spijkerman AMW: The Association Between BMI and Different Frailty Domains: A U-Shaped Curve? Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 2018, 22(1):8–15.

Teo N, Gao Q, Nyunt MSZ, Wee SL, Ng TP. Social Frailty and functional disability: findings from the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study I (SLAS-I). Australas J Ageing. 2018;7(18):e13–637.

Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, Makizako H, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, Kim M, Kurita S, Suzuki T, Shimada H. Social Frailty has a stronger impact on the onset of depressive symptoms than physical frailty or cognitive impairment: a 4-Year follow-up Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(6):504–10.

Yamada M, Arai H. Social Frailty Predicts Incident Disability and Mortality among Community-Dwelling Japanese older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(12):1099–103.

Hirase T, Makizako H, Okubo Y, Lord SR, Inokuchi S, Okita M. Chronic pain is independently associated with social frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(11):1153–6.

Jang I, Park H, Jung H, Lee Y, Lee E, Kim D. Prevalence of social frailty and its association with physical frailty and disability in community-dwelling older adults: aging study of Pyeongchang rural area. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:S128.

Makizako H, Kubozono T, Kiyama R, Takenaka T, Kuwahata S, Tabira T, Kanoya T, Horinouchi K, Shimada H, Ohishi M. Associations of social frailty with loss of muscle mass and muscle weakness among community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(1):76–80.

Nakakubo S, Doi T, Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Kurita S, Kim M, Ishii H, Suzuki T, Shimada H. Association of sleep condition and social frailty in community-dwelling older people. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(9):885–9.

Park H, Jang IY, Lee HY, Jung HW, Lee E, Kim DH. Screening Value of Social Frailty and Its Association with Physical Frailty and Disability in Community-Dwelling older koreans: Aging Study of PyeongChang Rural Area. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2809.

Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, Nakakubo S, Kim M, Kurita S, Ishii H, Shimada H, Kawachi I. Impact of Social Frailty on Alzheimer’s Disease Onset: a 53-Month Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD. 2019;70(2):587–95.

Verver D, Merten H, de Blok C, Wagner C. A cross sectional study on the different domains of frailty for independent living older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):61.

Yoo M, Kim S, Kim BS, Yoo J, Lee S, Jang HC, Cho BL, Son SJ, Lee JH, Park YS, et al. Moderate hearing loss is related with social frailty in a community-dwelling older adults: the Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study (KFACS). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;83:126–30.

Zhang X, Tan SS, Franse CB, Alhambra-Borrás T, Durá-Ferrandis E, Bilajac L, Markaki A, Verma A, Mattace-Raso F, Voorham AJJ, et al. Association between physical, psychological and social frailty and health-related quality of life among older people. Eur J Pub Health. 2019;29(5):936–42.

Hironaka S, Kugimiya Y, Watanabe Y, Motokawa K, Hirano H, Kawai H, Kera T, Kojima M, Fujiwara Y, Ihara K, et al. Association between oral, social, and physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104–5.

Huang CH, Okada K, Matsushita E, Uno C, Satake S, Arakawa Martins B, Kuzuya M. Sex-specific association between Social Frailty and Diet Quality, Diet Quantity, and Nutrition in Community-Dwelling Elderly. Nutrients 2020, 12(9).

Pek K, Chew J, Lim JP, Yew S, Tan CN, Yeo A, Ding YY, Lim WS. Social Frailty is independently Associated with Mood, Nutrition, Physical Performance, and physical activity: insights from a theory-guided Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17(12).

Zhang WY, Fan JY, Wang TY, Li J. Correlation between social frailty and depression in community elderly in Hubei Province. Practical Gerontol. 2021;35(05):491–4.

Peng XY, Zhang FSM, Luo W, Chen BB. Social frailty of the elderly in community and its influencing factors. Nurs Res. 2021;35(19):3401–6.

Chen ZK, Jiang XY, Shi GP, Wang Y, Chu XF, Wang ZD, Guo JH, Zhu YS, Chen J, Wang XF, et al. Social Frailty and longitudinal risk of depressive symptoms in a Chinese population: the Rugao Longevity and Aging Study. Psychogeriatrics: Official J Japanese Psychogeriatr Soc. 2021;21(4):483–90.

Huang CH, Okada K, Matsushita E, Uno C, Satake S, Martins BA, Kuzuya M. The association of social frailty with intrinsic capacity in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):515.

Ko H, Jung S. Association of Social Frailty with Physical Health, cognitive function, Psychological Health, and life satisfaction in Community-Dwelling Older koreans. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(2).

Ono R, Murata S, Uchida K, Endo T, Otani K. Reciprocal relationship between locomotive syndrome and social frailty in older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(11):981–4.

Song G, Wang Y, Gao HL, Chen L, Yang YL. Correlation between sleep disorders and social frailty in elderly people in community. Practical Gerontol. 2022;36(08):813–7.

Liu H, Lin X. Social frailty of the elderly in a community of Changsha City and its influencing factors. Occup Health. 2022;38(14):1978–81.

Hao J, FJ. Investigation on social frailty of community elderly in Hubei Province and analysis of influencing factors. Contemp Nurses. 2022;29(09):88–93.

Chen YW, Huang XH, Pu YH, Xu JX. Relationship between social frailty and quality of life of elderly people in community. Gerontol Health care. 2022;28(01):30–4.

Choi S, Ko H. Social Frailty among Community-Dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19(19).

Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Ishii H, Nakakubo S, Kurita S, Kiuchi Y, Nishimoto K, Shimada H. Impact of social frailty on the association between driving status and disability in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;99:104597.

Hayashi T, Noguchi T, Kubo Y, Tomiyama N, Ochi A, Hayashi H. Social Frailty and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults in Japan: role of home exercise habits. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;98:104555.

Ko Y, Lee K. Social Frailty and Health-Related Quality of Life in Community-Dwelling older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):56–9.

Kodama A, Kume Y, Lee S, Makizako H, Shimada H, Takahashi T, Ono T, Ota H. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic exacerbation of depressive symptoms for Social Frailty from the ORANGE Registry. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19(2).

Kume Y, Kodama A, Takahashi T, Lee S, Makizako H, Ono T, Shimada H, Ota H. Social Frailty is independently associated with geriatric depression among older adults living in northern Japan: a cross-sectional study of ORANGE registry. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022;22(2):145–51.

Miyata H, Maruta M, Makizako H, Han GH, Ikeda Y, Nakamura A, Tokuda K, Shimokihara S, Akaida S, Hidaka Y et al. Association between satisfaction with meaningful activities and social frailty in community-dwelling Japanese older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2022, 100.

Sugie M, Harada K, Nara M, Kugimiya Y, Takahashi T, Kitagou M, Kim H, Kyo S, Ito H. Prevalence, overlap, and interrelationships of physical, cognitive, psychological, and social frailty among community-dwelling older people in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;100:104659.

Ferreira LD, Araújo MD, Tavares DMD, Bolina AF. Quality of life and social vulnerability of older adults in the urban community: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;46:46–51.

Ragusa FS, Veronese N, Smith L, Koyanagi A, Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M. Social Frailty increases the risk of all-cause mortality: a longitudinal analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Exp Gerontol. 2022;167:111901.

Yang QJ, Xin XL, Zhang MM, Zhang L, Peng DM. Analysis of social weakness status quo and influencing factors of rural empty-nest elderly in Chengde City. Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database (full text) Social Sciences 2023(8).

Chen IC, Chang SH. The relationship between coronavirus-related anxiety on physical frailty, psychological frailty, and social frailty in older community- dwellers in Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Health Res. 2023;37(4):253–60.

Jeong HN, Chang SJ. Association between Social Frailty and life satisfaction among older adults: the Role of Functional limitations and depressive symptoms. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2023;16(6):291–300.

Qi X, Li YY, Hu JB, Meng LB, Zeng P, Shi J, Jia N, Zeng XZ, Li H, Zhang QX, et al. Prevalence of social frailty and its associated factors in the older Chinese population: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):532.

Sun QQ, Tan K, Tang HY, Liu YY, Zhu H, Qin H, Xia X, Zhang M, Chen YY, Nie SS, et al. Incidence and predictive value of social frailty among community-dwelling older adults in Southwest China: a prospective cohort study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1103651.

Yamada M, Arai H. Understanding social frailty. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;115:105–23.

Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487–92.

Qiu Y, Li G, Wang X, Zheng L, Wang C, Wang C, Chen L. Prevalence of cognitive frailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;125:104–12.

Collaborators GFF. 1950–2021, with forecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2021. Global fertility in 204 countries and territories. Lancet; 2024.

Hamid TA, Salih SA, Zillah Abdullah SF, Ibrahim R, Mahmud A. Characterization of social frailty domains and related adverse health outcomes in the Asia-Pacific: a systematic literature review. PeerJ. 2024;12:e17058.

Qi X, Li J. The relationship between Social Frailty and depressive symptoms in the Elderly: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):166–83.

Toros T, Ogras EB, Toy AB, Kulak A, Esen HT, Ozer SC, Celik T. The impact of regular Exercise on life satisfaction, Self-Esteem, and self-efficacy in older adults. Behav Sci (Basel Switzerland). 2023;13(9):714.

Ma W, Wu B, Gao X, Zhong R. Association between frailty and cognitive function in older Chinese people: a moderated mediation of social relationships and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2022;316:223–32.

Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(3):165–73.

Nagai K, Tamaki K, Kusunoki H, Wada Y, Tsuji S, Itoh M, Sano K, Amano M, Hayashitani S, Yokoyama R, et al. Physical frailty predicts the development of social frailty: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):403.

Li X, Gao L, Qiu Y, Zhong T, Zheng L, Liu W, Li G, Chen L. Social Frailty as a predictor of adverse outcomes among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2023;35(7):1417–28.

Acknowledgements

We thank West China Hospital of Sichuan University and West China College of Nursing of Sichuan University for technical support.

Funding

This study is supported by the 1·3·5 project for disciplines of excellence from West China Hospital of Sichuan University (ZYGD23015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL conducts major thesis writing, data extraction and data analysis, and article proofreading. LZ conducts thesis writing, data extraction and partial data analysis. YY, and YL provided ideas. HY, and PF provides ideas for papers and reviews articles. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Zhu, L., Yang, Y. et al. Prevalence and potential influencing factors for social frailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 24, 762 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05365-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05365-8