Abstract

Background

In recent years, as deep learning has received widespread attention in the field of heart disease, some studies have explored the potential of deep learning based on coronary angiography (CAG) or coronary CT angiography (CCTA) images in detecting the extent of coronary artery stenosis. However, there is still a lack of a systematic understanding of its diagnostic accuracy, impeding the advancement of intelligent diagnosis of coronary artery stenosis. Therefore, we conducted this study to review the accuracy of image-based deep learning in detecting coronary artery stenosis.

Methods

We retrieved PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science until April 11, 2023. The risk of bias in the included studies was appraised using the QUADAS-2 tool. We extracted the accuracy of deep learning in the test set and performed subgroup analyses by binary and multiclass classification scenarios. We performed a subgroup analysis based on different degrees of stenosis and applied a double arcsine transformation to process the data. The analysis was done by using R.

Results

Our systematic review finally included 18 studies, involving 3568 patients and 13,362 images. In the included studies, deep learning models were constructed based on CAG and CCTA. In binary classification tasks, the accuracy for detecting > 25%, > 50% and > 70% degrees of stenosis at the vessel level were 0.81 (95% CI: 0.71–0.85), 0.73 (95% CI: 0.58–0.88) and 0.61 (95% CI: 0.56–0.65), respectively. In multiclass classification tasks, the accuracy for detecting 0–25%, 25–50%, 50–70%, and 70–100% degrees of stenosis at the vessel level were 0.78 (95% CI: 0.73–0.84), 0.86 (95% CI: 0.78–0.93), 0.83 (95% CI: 0.70–0.97), and 0.70 (95% CI: 0.42–0.98), respectively.

Conclusions

Our study shows that deep learning models based on CAG and CCTA appear to be relatively accurate in diagnosing different degrees of coronary artery stenosis. However, for various degrees of stenosis, their accuracy still needs to be further improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most prevalent heart disease [1] and affects 7.2% of adults aged ≥ 20 in the United States [2]. It is a particular health concern in densely populated countries [3]. CAD mainly manifests as coronary artery stenosis, which arises from plaques within arteries caused by the deposition of cholesterol, calcium, and fat [4]. These plaques can obstruct arteries, and then restrict oxygen-rich blood flowing into the heart, potentially leading to fatal outcomes. Consequently, accurately quantifying the degree of coronary artery stenosis is crucial for early diagnosis, risk assessment, and the management of CAD [5]. Early identification and management of CAD is essential in clinical practice since it can reduce the risk of acute coronary events and sudden death.

While invasive coronary angiography (CAG) is still the gold standard for the diagnosis of stenosis [6], several non-invasive techniques are available, such as Electron Beam Computed Tomography (EBCT), Multi-Detector Computed Tomography (MDCT), and Coronary Magnetic Resonance Angiography [7]. However, these methods heavily rely on clinical practitioners’ expertise and experience. With recent advancements in artificial intelligence and statistical theory, image-based artificial intelligence has been successfully applied to the diagnosis and treatment of diseases in clinical practice. The application of artificial intelligence in the medical field, particularly deep learning, has garnered significant attention from researchers. Deep learning has been widely utilized across various domains, including drug discovery and biomedical signal analysis. For instance, neural network-based models have been effectively employed to predict drug permeability across the placenta [8]. Machine learning approaches, integrating fingerprint amalgamation and data balancing, have been used to comprehensively analyze drug permeability through the blood-brain barrier [9]. Additionally, deep learning methods have been applied to estimate age and gender from electrocardiogram signals [10], and food recognition has been automated via deep learning models [11]. Over the past decade, deep learning has made significant advancements in medical information science and image analysis [12], particularly through the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). CNNs have made notable advancements in fields like computer vision and speech recognition. For example, efficient CNNs such as ConvUNeXt and DRU-Net have been developed for medical image segmentation [13, 14], highlighting the strengths of deep learning in ultrasound image segmentation [15]. Additionally, neural networks with improved segmentation accuracy have been developed for liver CT image segmentation and liver ultrasound image segmentation. [16, 17]. Researchers have proposed a new framework that can effectively bridge CNNs and transformers (Cotr) for precise 3D medical image segmentation [18]. In the context of liver tumor diseases, image segmentation serves as the first step for clinicians in optimizing diagnosis, staging, treatment planning, and interventions, which could potentially impact diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes [19]. Additionally, researchers have explored the risk assessment of computer-aided diagnostic software for hepatic resection [20]and evaluated the effectiveness of fusion imaging for immediate post-ablation assessment of malignant liver neoplasms [21]. Deep learning also appears to show promising results in the diagnosis of certain complex cardiac diseases. For instance, artificial intelligence and deep neural networks have been employed to identify electrocardiographically concealed long QT syndrome using surface 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs), demonstrating their potential in the intelligent diagnosis of diseases [22].

In this context, some researchers have explored deep learning models based on coronary angiography (CAG) or coronary CT angiography (CCTA) images to identify the degree of coronary artery stenosis. Nevertheless, comprehensive evidence substantiating their efficacy remains insufficient. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis of previously published studies to provide the following evidence for the use of deep learning in the diagnosis of coronary artery stenosis: (1) A review of the accuracy of deep learning in differentiating various levels of coronary artery stenosis based on CAG or CCTA; (2) A review of the accuracy of deep learning in diagnosing coronary artery stenosis for both binary classification and multiclass classification tasks.

Methods

Study registration

This study was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines and prospectively registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42023444635).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

(1)

Studies that have fully developed deep learning models for identifying the degree of coronary artery stenosis, including both binary classification and multiclass classification tasks.

-

(2)

Some studies may utilize the same publicly available database. We acknowledged the contributions of these studies, and included various deep learning investigations conducted on the same dataset.

-

(3)

In previous research, there may be a small number of studies that have validated previously developed deep learning models. These studies were also included in our systematic review.

-

(4)

The types of studies included were case-control studies, cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies.

-

(5)

Studies had to be written in English.

Exclusion criteria

-

(1)

Meta-analyses, reviews, guidelines, and expert opinions were excluded.

-

(2)

Studies lacking model validation were excluded.

-

(3)

Studies did not report the following outcome measures for model accuracy: ROC, c-statistic, c-index, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, recovery, precision, confusion matrix, diagnostic fourfold table, F1 score, and calibration curve.

-

(4)

Studies solely focused on image segmentation and reconstruction.

Data sources and search strategy

PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science were thoroughly retrieved up to April 11, 2023. Both MeSH terms and free-text keywords were used, without restrictions on publication region or year. Details of the search strategy are available in Table S1.

Study selection and data extraction

All identified articles were imported into EndNote software. Duplicates were automatically and manually removed. After checking titles and abstracts, we deleted irrelevant studies. The full texts of the remaining articles were reviewed to determine eligible studies.

A structured form was used to extract data, including title, first author, year of publication, author’s country, study type, patient source, image source, diagnostic criteria for coronary artery stenosis, degree of coronary artery stenosis, total number of cases, number of coronary artery stenosis cases in training set, total number of cases in training set, generation methods of validation set, number of coronary artery stenosis cases in validation set, number of cases in validation set, and the type of models used. The literature screening and data extraction were independently implemented by two researchers, followed by cross-checking. Any dissents were addressed by a third researcher (a cardiology expert).

Risk of bias assessment

The QUADAS-2 tool (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2) was leveraged to discern the risk of bias and applicability of the included studies [23]. This tool encompassed specific questions in four aspects: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. Each question was answered as Yes, No, or Unclear, which suggested a low, high, or unclear risk of bias, respectively. Studies were graded at low risk of bias if all key questions in each domain were answered with Yes. If all signal questions were answered as No, there was potential bias. An unclear risk was considered if there was no sufficient information for a definitive judgment.

The quality assessment was independently conducted by two researchers (a clinician with 5 years of experience in cardiology and a clinician with over 5 years of cardiology experience). Then their results were cross-checked. Discrepancies were resolved by a third researcher (a cardiology expert).

Outcomes

This study assessed the accuracy of deep learning in detecting the degree of coronary artery stenosis. Notably, the degree thresholds for defining stenosis were inconsistent across studies from different countries, and > 25%, > 50%, and > 70% were mainly used.

Synthesis methods

Since a limited number of the included studies reported the number of cases and images of different stenosis degrees, we failed to perform the planned meta-analysis using a bivariate mixed-effects model and diagnostic 2 × 2 tables, as described in the registered protocol. Consequently, a meta-analysis of sensitivity was conducted instead. Heterogeneity across studies was examined utilizing the Q test and I² index. A fixed-effects model was employed for meta-analysis if I² <50%, while a random-effects model was applied if I² >50%. Subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, and meta-regression analyses were implemented to discern the sources of heterogeneity.

Results

Study selection

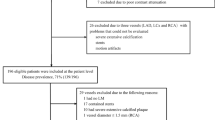

A total of 2,139 reports were identified from PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science. After the removal of 749 duplicate publications, titles and abstracts were checked, and 42 potentially relevant studies were selected. After a thorough full-text review, 18 studies were eligible and included [4, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. The literature screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

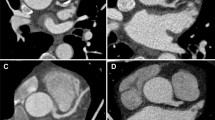

The 18 included studies encompassed 3,568 patients and 13,362 vascular images. These studies were published between 2019 and 2023, and these studies were conducted in China, the United States, Australia, Japan, Mexico, Portugal, and the Netherlands. Five studies were multicenter studies [25, 32, 33, 35, 37], while the remaining were single-center studies. Regarding image sources, 3 studies relied solely on CAG images [27, 28, 31], 11 utilized only CCTA images [4, 24,25,26, 28,29,30, 33, 37,38,39], and 4 used both modalities [27, 32, 35, 36]. Twelve studies used binary classification tasks [24,25,26, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34,35,36], while six focused on multiclass tasks [4, 27, 30, 33, 37, 38]. The threshold for defining coronary artery stenosis varied across studies, with > 25%, > 50%, and > 70% being the most commonly used. Five studies used 25% as the threshold for defining coronary artery stenosis [26, 28, 30, 33, 37], seven used 50% [24, 25, 28, 32, 36,37,38], four used 70% [30, 33, 37, 38], and two did not explicitly define the threshold [4, 35]. Detailed information is provided in Table 1.

Risk of bias

While all included studies employed a case-control design, this design did not impact the assessment of the performance of deep learning. Thus, the risk of bias in patient selection is considered low. Additionally, although the included studies did not describe whether the index tests were interpreted without the knowledge of the results of the reference standard, their results were obtained using artificial intelligence, which did not affect the assessment of the performance of deep learning. As such, the risk of bias in the index test was also deemed low. Besides, most studies lacked explicit information on the blinding in the assessment of the reference standard. However, there was a reasonable interval between the index tests and reference standard, and all patients received a reference standard, suggesting a low risk of bias in flow and timing.

Meta-analysis

Binary classification tasks

For binary classification tasks, most studies mainly used < 50% and > 50% as the threshold for defining coronary artery stenosis, while limited studies used 25% and 70%. Based on vascular images, the meta-analysis revealed that the accuracy of deep learning models was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.64–0.94) for detecting < 50% stenosis and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.58–0.88) for > 50% stenosis. However, the results for 25% and 70% stenosis should be interpreted with caution (Fig. 2). Likewise, based on patients, the meta-analysis showed higher performance of deep learning models in the diagnosis of < 50% stenosis (0.83, 95% CI: 0.74–0.93) compared to > 50% stenosis (0.79, 95% CI: 0.66–0.91) (Fig. 3).

Based on vascular images, the meta-analysis showed that the accuracy of CCTA-based models was 0.80 (95% CI: 0.76–0.84) for detecting < 50% stenosis, 0.76 (95% CI: 0.53–0.99) for > 50% stenosis, 0.81 (95% CI: 0.76–0.84) for < 25% stenosis, and 0.81 (95% CI: 0.75–0.88) for > 25% stenosis (Fig. 4). Based on patients, the meta-analysis revealed that the accuracy of these models was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.67–1.07) for detecting < 50% stenosis, 0.70 (95% CI: 0.62–0.79) for > 50% stenosis, 0.85 (95% CI: 0.81–0.90) for < 25% stenosis, and 0.72 (95% CI: 0.62–0.82) for > 25% stenosis (Fig. 5).

Multiclass classification tasks

For multiclass classification tasks, based on vascular images, the meta-analysis revealed that the accuracy of deep learning models was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.73–0.84) for detecting 0–25% stenosis, 0.86 (95% CI: 0.78–0.93) for 25–50% stenosis, 0.83 (95% CI: 0.70–0.97) for 50–70% stenosis, and 0.70 (95% CI: 0.42–0.98) for 70–100% stenosis (Fig. 6). Based on patients, the meta-analysis revealed that the accuracy of deep learning models was 0.72 (95% CI: 0.48–0.95) for detecting 0–25% stenosis, 0.78 (95% CI: 0.55–1.00) for 25–50% stenosis, 0.65 (95% CI: 0.30–1.00) for 50–70% stenosis, and 0.74 (95% CI: 0.54–0.94) for 70–100% stenosis (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Summary of the main findings

Deep learning is relatively accurate in detecting coronary artery stenosis, especially > 50% and < 50% stenosis. In binary classification tasks, the accuracy of deep learning models in detecting < 50% stenosis at the vessel level was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.64–0.94), and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.58–0.88) for > 50% stenosis. In the multiclass classification tasks, the accuracy was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.78–0.93) for 25–50% stenosis and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.70–0.97) for 50–70% stenosis.

Coronary artery stenosis is often caused by atherosclerosis which narrows the coronary artery lumens. In most studies, significant stenosis is typically defined as a 50% or higher degree of stenosis [40]. The treatment of CAD primarily relies mainly on drugs, often combined with reperfusion therapies through interventional procedures or bypass surgery. These treatments aim to improve coronary blood flow, prevent cardiovascular events, and enhance quality of life [41]. The specific treatment approach would be formulated according to the severity and number of coronary artery stenosis. Existing studies mainly focus on significant stenosis (> 50%). Our findings demonstrate the high accuracy of deep learning in detecting stenosis > 50%, suggesting that deep learning is a feasible technique.

Recent research has mainly used image-based techniques to detect coronary artery stenosis. Song-Bai Deng et al. [42] reported that FFRCT showed a sensitivity of 90% (95% CI: 85–93%) and a specificity of 72% (95% CI: 67–76%) in the diagnosis of CAD. A review by Zhenhua Xing et al. [43] described the accuracy of quantitative flow ratio (QFR) in the assessment of moderate coronary artery stenosis, with a sensitivity of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.86–0.92) and a specificity of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.86–0.91). Shun-Lin Guo [44] reported that dual-source computed tomography (DSCT) achieved a sensitivity of 0.957 (95% CI: 0.943–0.969) and specificity of 0.930 (95% CI: 0.910–0.940) in the diagnosis of CADs when the degree of ≥ 50% was used as the threshold to define significant stenosis. Although these studies have reported promising performance of deep learning in binary classification tasks, they overlook multiclass scenarios. However, assessing varying degrees of coronary artery stenosis is prevalent in clinical practice. Hence, our comprehensive review highlights favorable performance of machine learning in the diagnosis of vascular stenosis in multiclass settings, with an accuracy rate of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.73–0.84) for 0–25% stenosis, 0.86 (95% CI: 0.78–0.93) for 25–50% stenosis, and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.70–0.97) for 50–70% stenosis.

Image segmentation is a key technique in the field of computer vision. It involves the process of dividing an image into multiple regions or objects [45]. In medical imaging, particularly in cardiovascular imaging, segmentation is a critical step for enhancing the diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases [46]. Segmenting images facilitates the extraction of quantitative data, such as the degree of luminal stenosis, plaque burden, and arterial wall thicknes [47]. Additionally, segmented images can provide a clear and detailed visual representation of the coronary arteries, which enables clinicians to easily identify areas of concern [48]. Reproducibility in image segmentation is vital for disease detection, yet it remains a significant challenge in ongoing research [20]. Segmented images can be integrated with other diagnostic modalities, such as CT angiography, MR angiography, or intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), to provide a comprehensive assessment of coronary artery disease [49, 50]. Segmentation methods include automated and semi-automated approaches based on deep learning, as well as manual segmentation. Deep learning-based segmentation reduces the time and effort required for manual segmentation and minimizes human error [51]. In current research, segmented images are often analyzed using specialized software to extract texture features, which are then used to construct traditional machine learning models for disease diagnosis or prognosis prediction [52, 53]. These approaches have shown promising results. Similarly, researchers can adopt deep learning methods to directly train on segmented images for disease diagnosis. In the diagnosis of certain diseases, deep learning appears to have advantages over traditional machine learning [54]. In the original studies included in our systematic review, the research focused on deep learning models built on image segmentation, which demonstrated promising accuracy in improving the identification of coronary artery stenosis.

Nowadays, artificial intelligence research based on imaging faces several great challenges. The development of AI across different imaging modalities presents certain difficulties. For example, in the study by Snigdha Mohanty et al. [55], a novel non-rigid method was introduced to register both the same and cross-imaging modalities, such as MRI, CT, and 3D rotational angiography. Even within the same modality, the impact of noise during the image segmentation process remains a serious challenge in practical applications [56, 57]. The speed of segmentation during the process is also a challenge, and some researchers have been exploring solutions to improve running speed [58]. Additionally, in manual segmentation, the reproducibility of results remains a significant challenge due to the reliance on the prior knowledge of human experts.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to discuss the accuracy of deep learning in detecting coronary artery stenosis, providing valuable evidence for future research. However, it still has some limitations. First, despite our systematic search, the number of the included studies is limited. Therefore, more studies are required for validation in the future. Second, these studies employed diverse thresholds for defining coronary artery stenosis, with some thresholds analyzed in only a few studies. Hence, the results should be interpreted cautiously. Third, the models were mainly built on both CCTA and CAG images and seldom on CAG images, and thus the results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

In summary, deep learning methods have recently gained significant attention and have been widely used in the intelligent detection of coronary artery stenosis. Our meta-analysis reveals that these methods are relatively accurate for detecting coronary artery stenosis. Existing studies focus on both binary and multiclass classification tasks, but actually, the latter appears more applicable to clinical practice. However, accurately detecting smaller degrees of stenosis in multi-class settings remains challenging. Therefore, future research is needed to develop more efficient deep learning models to enhance the detection of coronary artery stenosis.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, et al. Executive Summary: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2016 update: a Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):447–54.

Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, Boehme AK, Buxton AE, Carson AP, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 update: a Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153–639.

The W. Report on Cardiovascular Health and diseases in China 2022: an updated Summary. Biomed Environ Sci. 2023;36(8):669–701.

Zhu H, Song S, Xu L, Song A, Yang B. Segmentation of coronary arteries images using spatio-temporal feature Fusion Network with Combo loss. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2022;13(3):407–18.

Norris RM, White HD, Cross DB, Wild CJ, Whitlock RM. Prognosis after recovery from myocardial infarction: the relative importance of cardiac dilatation and coronary stenoses. Eur Heart J. 1992;13(12):1611–8.

Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, Prescott E, Storey RF, Deaton C, Cuisset T, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(3):407–77.

Pakkal M, Raj V, McCann GP. Non-invasive imaging in coronary artery disease including anatomical and functional evaluation of ischaemia and viability assessment. Br J Radiol. 2011;84(Spec 3):S280–295. Spec Iss 3.

Chandrasekar V, Ansari MY, Singh AV, Uddin S, Prabhu KS, Dash S, Khodor SA, Terranegra A, Avella M, Dakua SP. Investigating the Use of Machine Learning models to understand the drugs permeability across Placenta. IEEE Access. 2023;11:52726–39.

Ansari MY, Chandrasekar V, Singh AV, Dakua SP. Re-routing drugs to blood brain barrier: a Comprehensive Analysis of Machine Learning approaches with fingerprint amalgamation and data balancing. IEEE Access. 2023;11:9890–906.

Ansari MY, Qaraqe M, Charafeddine F, Serpedin E, Righetti R, Qaraqe K. Estimating age and gender from electrocardiogram signals: a comprehensive review of the past decade. Artif Intell Med. 2023;146:102690.

Ansari MY, Qaraqe M. MEFood: a large-scale Representative Benchmark of Quotidian Foods for the Middle East. IEEE Access. 2023;11:4589–601.

Yuan D, Li X, He Z, Liu Q, Lu S. Visual object tracking with adaptive structural convolutional network. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;194:105554.

Han Z, Jian M, Wang G-G. ConvUNeXt: an efficient convolution neural network for medical image segmentation. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;253:109512.

Jafari M, Auer DP, Francis ST, Garibaldi JM, Chen X. DRU-Net: An Efficient Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Medical Image Segmentation. 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 2020:1144–1148.

Ansari MY, Mangalote IAC, Meher PK, Aboumarzouk O, Al-Ansari A, Halabi O, Dakua SP. Advancements in Deep Learning for B-Mode Ultrasound Segmentation: a Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput Intell. 2024;8(3):2126–49.

Ansari MY, Yang Y, Balakrishnan S, Abinahed J, Al-Ansari A, Warfa M, Almokdad O, Barah A, Omer A, Singh AV, et al. A lightweight neural network with multiscale feature enhancement for liver CT segmentation. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):14153.

Ansari MY, Yang Y, Meher PK, Dakua SP. Dense-PSP-UNet: a neural network for fast inference liver ultrasound segmentation. Comput Biol Med. 2023;153:106478.

Xie Y, Zhang J, Shen C, Xia Y. CoTr: efficiently bridging CNN and Transformer for 3D medical image segmentation. In: 2021; Cham. Springer International Publishing; 2021. pp. 171–80.

Ansari MY, Abdalla A, Ansari MY, Ansari MI, Malluhi B, Mohanty S, Mishra S, Singh SS, Abinahed J, Al-Ansari A, et al. Practical utility of liver segmentation methods in clinical surgeries and interventions. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22(1):97.

Akhtar Y, Dakua SP, Abdalla A, Aboumarzouk OM, Ansari MY, Abinahed J, Elakkad MSM, Al-Ansari A. Risk Assessment of computer-aided Diagnostic Software for hepatic resection. IEEE Trans Radiation Plasma Med Sci. 2022;6(6):667–77.

Rai P, Ansari MY, Warfa M, Al-Hamar H, Abinahed J, Barah A, Dakua SP, Balakrishnan S. Efficacy of fusion imaging for immediate post-ablation assessment of malignant liver neoplasms: a systematic review. Cancer Med. 2023;12(13):14225–51.

Bos JM, Attia ZI, Albert DE, Noseworthy PA, Friedman PA, Ackerman MJ. Use of Artificial Intelligence and deep neural networks in evaluation of patients with Electrocardiographically concealed Long QT Syndrome from the surface 12-Lead Electrocardiogram. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(5):532–8.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

Han X, He Y, Luo N, Zheng D, Hong M, Wang Z, Yang Z. The influence of artificial intelligence assistance on the diagnostic performance of CCTA for coronary stenosis for radiologists with different levels of experience. Acta Radiol. 2023;64(2):496–507.

Griffin WF, Choi AD, Riess JS, Marques H, Chang HJ, Choi JH, Doh JH, Her AY, Koo BK, Nam CW, et al. AI evaluation of stenosis on coronary CTA, comparison with quantitative coronary angiography and fractional Flow Reserve: a CREDENCE Trial Substudy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;16(2):193–205.

Cong C, Kato Y, Vasconcellos HD, Ostovaneh MR, Lima JAC, Ambale-Venkatesh B. Deep learning-based end-to-end automated stenosis classification and localization on catheter coronary angiography. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:944135.

Ling H, Chen B, Guan R, Xiao Y, Yan H, Chen Q, Bi L, Chen J, Feng X, Pang H, et al. Deep learning model for coronary angiography. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2023;16(4):896–904.

Yi Y, Xu C, Guo N, Sun J, Lu X, Yu S, Wang Y, Vembar M, Jin Z, Wang Y. Performance of an Artificial Intelligence-based application for the detection of plaque-based stenosis on Monoenergetic Coronary CT Angiography: validation by Invasive Coronary Angiography. Acad Radiol. 2022;29(Suppl 4):S49–58.

Sehly A, He A, Jaltotage B, Lan NSR, Joyner J, Flack J, Sokolov J, Chronos N, Ko B, Chow B et al. Coronary artery stenosis and vulnerable plaque quantification on CCTA by deep learning methods. Eur Heart J 2022, 43(Supplement_2).

Jin X, Li Y, Yan F, Liu Y, Zhang X, Li T, Yang L, Chen H. Automatic coronary plaque detection, classification, and stenosis grading using deep learning and radiomics on computed tomography angiography images: a multi-center multi-vendor study. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(8):5276–86.

Yabushita H, Goto S, Nakamura S, Oka H, Nakayama M, Goto S. Development of Novel Artificial Intelligence to detect the Presence of clinically meaningful coronary atherosclerotic stenosis in Major Branch from Coronary Angiography Video. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2021;28(8):835–43.

Xu L, He Y, Luo N, Guo N, Hong M, Jia X, Wang Z, Yang Z. Diagnostic accuracy and generalizability of a deep learning-based fully automated algorithm for coronary artery stenosis detection on CCTA: a Multi-centre Registry Study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:707508.

Choi AD, Marques H, Kumar V, Griffin WF, Rahban H, Karlsberg RP, Zeman RK, Katz RJ, Earls JP. CT evaluation by Artificial Intelligence for Atherosclerosis, stenosis and vascular morphology (CLARIFY): A multi-center, international study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2021;15(6):470–6.

Yin W, Li X, Hou Z, An Y, Budoff M, Lu B. Deep Learning Versus radiologists Visual Assessment to identify plaque and stenosis at coronary ct angiography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020;14(3, Supplement):S21.

Ovalle-Magallanes E, Avina-Cervantes JG, Cruz-Aceves I, Ruiz-Pinales J. Transfer learning for stenosis detection in X-ray coronary angiography. Mathematics. 2020;8(9):1510.

Han D, Liu J, Sun Z, Cui Y, He Y, Yang Z. Deep learning analysis in coronary computed tomographic angiography imaging for the assessment of patients with coronary artery stenosis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;196:105651.

Choi A, Marques H, Kumar V, Griffin W, Lichtenberger J, Zeman R, Katz R, Earls J. Automated Artificial Intelligence-based interpretation of coronary CTA: determination of stenosis severity compared with Level III Expert readers. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020;14(3):S22.

Zreik M, van Hamersvelt RW, Wolterink JM, Leiner T, Viergever MA, Isgum I. A recurrent CNN for Automatic Detection and classification of coronary artery plaque and stenosis in coronary CT angiography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019;38(7):1588–98.

Halpern EJ, Halpern DJ. Diagnosis of coronary stenosis with CT angiography comparison of automated computer diagnosis with expert readings. Acad Radiol. 2011;18(3):324–33.

Gould KL, Lipscomb K. Effects of coronary stenoses on coronary flow reserve and resistance. Am J Cardiol. 1974;34(1):48–55.

Doenst T, Thiele H, Haasenritter J, Wahlers T, Massberg S, Haverich A. The treatment of coronary artery disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119(42):716–23.

Deng SB, Jing XD, Wang J, Huang C, Xia S, Du JL, Liu YJ, She Q. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:703–9.

Xing Z, Pei J, Huang J, Hu X, Gao S. Diagnostic performance of QFR for the evaluation of Intermediate Coronary Artery Stenosis confirmed by fractional Flow Reserve. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;34(2):165–72.

Guo SL, Guo YM, Zhai YN, Ma B, Wang P, Yang KH. Diagnostic accuracy of first generation dual-source computed tomography in the assessment of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis from 24 studies. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;27(6):755–71.

Dakua SP. Use of chaos concept in medical image segmentation. Comput Methods Biomech Biomedical Engineering: Imaging Visualization. 2013;1(1):28–36.

Tatsugami F, Nakaura T, Yanagawa M, Fujita S, Kamagata K, Ito R, Kawamura M, Fushimi Y, Ueda D, Matsui Y, et al. Recent advances in artificial intelligence for cardiac CT: enhancing diagnosis and prognosis prediction. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2023;104(11):521–8.

Lee SN, Lin A, Dey D, Berman DS, Han D. Application of quantitative Assessment of Coronary atherosclerosis by Coronary computed Tomographic Angiography. Korean J Radiol. 2024;25(6):518–39.

Kumari V, Kumar N, Kumar KS, Kumar A, Skandha SS, Saxena S, Khanna NN, Laird JR, Singh N, Fouda MM et al. Deep learning paradigm and its Bias for Coronary Artery Wall Segmentation in Intravascular Ultrasound scans: a closer look. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023, 10(12).

Gharleghi R, Chen N, Sowmya A, Beier S. Towards automated coronary artery segmentation: a systematic review. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;225:107015.

Dakua SP. AnnularCut: a graph-cut design for left ventricle segmentation from magnetic resonance images. IET Image Proc. 2014;8(1):1–11.

Al-Kababji A, Bensaali F, Dakua SP, Himeur Y. Automated liver tissues delineation techniques: a systematic survey on machine learning current trends and future orientations. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;117:105532.

Tabnak P, HajiEsmailPoor Z, Baradaran B, Pashazadeh F, Aghebati Maleki L. MRI-Based Radiomics methods for Predicting Ki-67 expression in breast Cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Acad Radiol. 2024;31(3):763–87.

Yang Z, Gong J, Li J, Sun H, Pan Y, Zhao L. The gap before real clinical application of imaging-based machine-learning and radiomic models for chemoradiation outcome prediction in esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2023;109(8):2451–66.

Bedrikovetski S, Dudi-Venkata NN, Maicas G, Kroon HM, Seow W, Carneiro G, Moore JW, Sammour T. Artificial intelligence for the diagnosis of lymph node metastases in patients with abdominopelvic malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Artif Intell Med. 2021;113:102022.

Mohanty S, Dakua SP. Toward Computing Cross-modality symmetric Non-rigid Medical Image Registration. IEEE Access. 2022;10:24528–39.

Dakua SP, Abinahed J, Al-Ansari A. Semiautomated hybrid algorithm for estimation of three-dimensional liver surface in CT using dynamic cellular automata and level-sets. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2015;2(2):024006.

Dakua SP. LV Segmentation using Stochastic Resonance and Evolutionary Cellular Automata. Int J Pattern Recognit Artif Intell. 2015;29(03):1557002.

Zhai X, Amira A, Bensaali F, Al-Shibani A, Al-Nassr A, El-Sayed A, Eslami M, Dakua SP, Abinahed J. Zynq SoC based acceleration of the lattice boltzmann method. Concurrency Computation: Pract Experience. 2019;31(17):e5184.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Writing - original draft preparation: Li Tu; Writing - review and editing: Li Tu; Conceptualization: Li Tu; Methodology: Ying Deng, Li Tu; Formal analysis and investigation: Li Tu, Yun Chen; Funding acquisition: Ying Deng; Resources: Yun Chen, Yi Luo; Supervision: Ying Deng, Yun Chen, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, L., Deng, Y., Chen, Y. et al. Accuracy of deep learning in the differential diagnosis of coronary artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Imaging 24, 243 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-024-01403-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-024-01403-4