Abstract

Background

Horseshoe kidney is the most common renal fusion anomaly, and Wilms tumor is the most frequent renal malignancy in children. The occurrence of Wilms tumor in association with horseshoe kidney is a scarce anomaly. However, the arising of a teratoid type, which is a rare variant of Wilms tumor in a horseshoe kidney, is exceptionally unique.

Case presentation

This report presents a 5-year-old male admitted with horseshoe kidney involved by a large heterogeneous calcified mass that was diagnose on biopsy as Wilms tumor blastemal dominant. According to the local and regional extension and metastatic tumor in the lungs, the patient underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then surgery. Post-operative pathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of teratoid Wilms tumor.

Conclusions

The occurrence of renal anomalies associated with a malignancy might be more frequent in the clinical environment. There are numerous differential diagnoses for renal tumors and masses, but the possibility of exceptional anomalies should not be denied, and clinicians should be prepared for these occasions. Although studies propose that chemotherapy has a trivial effect on teratoid Wilms tumors, it is essential to evaluate the tumor for any possibility of regression in non-teratoid regions before proceeding to upfront tumoral resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The horseshoe kidney is the most typical renal fusion anomaly amongst children (0.25%) and is associated with a broad diversity of urological and non-urological anomalies [1]. Wilms tumor is the most common renal malignancy and the third most common solid malignancy in pediatrics [2]. The occurrence of Wilms tumor in a horseshoe kidney is a rare identification (0.4%—0.9%) [3], and a teratoid Wilms tumor emerging in a horseshoe kidney is considerably unique (around 30 cases reported in the literature with favorable outcomes) [4]. This report presents a case of internal teratoid Wilms tumor identified in a horseshoe kidney and describes the diagnosis procedures, neoadjuvant chemotherapy and tumor resection.

Case presentation

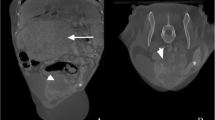

A 5-year-old male was referred to the pediatric hospital due to the detection of an unidentified abdominal mass in ultrasonography. He presented with intermittent fever, hematuria, and anorexia for two days. The patient’s vital signs were within normal ranges, and he had not been prescribed any medication before his visit. Laboratory studies revealed normal complete blood count, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and uric acid, but C-reactive protein was above the normal range (34.3 mg/L). Urinalysis indicated hematuria (+ + +) and proteinuria (+ +). Another ultrasonography was carried out and showed a fusion of the lower poles of both kidneys in front of the descending aorta and identified the horseshoe kidney. It was also stated that the family has no history of horseshoe kidney. The liver and spleen were normal. A heterogeneous mass with calcification foci about 120 × 109 × 92 mm on the right kidney with necrotic and cystic regions and retrocaval lymphadenopathy with a maximum size of 25 × 30 mm were found. An abdominal CT scan was performed, and the results matched the ultrasonography results (Fig. 1). A thoracic CT scan was also performed and revealed metastasis and increased peripheral densities in dependent segments of both lungs (Fig. 2). In addition, as a routine procedure after hospital admission, a Polymerase chain reaction test was performed to rule out any possible Covid-19 involvement, which was negative. Due to the presence of the calcified renal tumor, a preliminary diagnosis of Wilms tumor or neuroblastoma was established, and to determine the definite diagnosis an open biopsy was performed instead of core needle biopsy because of tumor inaccessibility (horseshoe kidney) and high risk of bleeding. Immunohistochemistry revealed the expression of Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) and PAX8 biomarkers, and none of the neuroblastoma markers were found, and microscopic evaluation showed the presence of a Wilms tumor blastemal cell dominant. In accordance with these findings, the pathology department made a diagnosis of Wilms tumor (stage 4). Concerning the tumor size and the horseshoe kidney, an up-front surgery according to the National Wilms Tumor Study-5 (NWTS-5) protocol was not possible. Therefore, the patient underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine, actinomycin-D, and doxorubicin. After 6 weeks of chemotherapy, the lung metastases were completely resolved but primary flank tumor was still unresectable. After 12 weeks of chemotherapy, a follow-up CT scan was conducted, and the tumor regressed to 74 × 85 × 105 mm and no lung metastasis was present. Then the patient was referred to the surgery department for tumor resection (right total nephrectomy) (Fig. 3). Lymph node dissection or sampling was not done at the discretion of the surgeon. After removing the tumor, it was sent to the pathology department for further evaluation, and the tumor turned out to be a teratoid Wilms tumor. The macroscopic evaluation of the resected tumor indicated a solid-cystic tumoral mass with extensive necrosis regions. Viable residual tumor was estimated about 20% of the main tumoral mass with an elastic consistency (Fig. 4a). Microscopic findings were the teratoid Wilms tumor with blastemal, stromal, and epithelial cells mixed with heterologous elements with no evidence of anaplasia, no nephrogenic rest, and no renal sinus or intrarenal vessels’ invasion (Fig. 4b). The surgical margins were free of tumor. The final tumor staging was determined as stage IV. After surgery, the patient underwent the adjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and etoposide for about 31 weeks. After the completion of adjuvant chemotherapy cycles, the patient was released from the hospital and instructed to revisit every three months (two times), six months (two times), and annually for follow-up (blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, urine culture/analysis, and abdomen/pelvic sonography). Serum creatinine levels after nephrectomy and during chemotherapy cycles were in normal range (0.8–1 mg/dL).

Discussion and conclusions

Although the identification of horseshoe kidneys in pediatrics is common [5], the chance of Wilms tumor occurrence in these patients is sparse [3, 6, 7]. Furthermore, horseshoe kidneys would increase the likelihood of developing urological abnormalities such as pelvic-ureteric junction obstruction and vesicoureteral reflux (10–80% and 25% respectively) and Wilms tumor two times higher than the average population [8,9,10]. There are speculations about the etiology of Wilms tumor in patients diagnosed with horseshoe kidneys. Some suggest the Wilms tumor is a consequence of sequestered metanephric tissues blastemas in the isthmus. In contrast, others believe the embryonic lesion that leads to horseshoe kidney would make the kidney prone to other abnormalities such as Wilms tumor [3, 9]. It is now clear that several Wilms tumor-related genes play a crucial role in the development of the kidney, and this tumor can emerge from deviant fetal nephrogenesis [11]. One study demonstrated that Wilms tumors are linked to the presence of nephrogenic rests [10]. These metanephric tissues may undergo hyperplasia or neoplasia, which may lead to the development of the Wilms tumor [12]. Research on children with WAGR syndrome showed deletions in chromosome 11p13, leading to the discovery of WT1 and PAX6 [13, 14]. In our case, excluding the tumor, the only anomaly was the presence of a horseshoe kidney with no previous history of hospitalization. This indicates that congenital abnormalities (in this case, horseshoe kidney) would increase the chance of developing urological anomalies [15]. Because Wilms tumor and neuroblastoma are the most common retroperitoneal tumors in pediatrics, our first differentiated diagnoses were between those two. Teratoid Wilms tumors are associated with calcified densities [10, 16] and are recognizable for their heterotopic organ formation [17]. The presence of calcification foci in the CT scan and the absence of heterotopic organ formation in the biopsy were the primary sources of our uncertainty for a definite pre-operative diagnosis. Microscopic evaluations of the resected tumor resolved these concerns because of cartilage and bone formations that led to the generation of calcified densities. Also, another helping factor in distinguishing teratoid Wilms tumor is the deletion of the short arm of chromosome 11 [18], which the patient’s family could not afford the procedure. There are several treatment protocols to manage pediatrics with Wilms Tumors, and the two significant advocates of these protocols are National Wilms Tumor Study (NWTS) and International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP). Regarding histopathological findings, NWTS favors upfront nephrectomy with the addition of a thoracic CT scan for possible metastasis, while SIOP prefers pre-operative chemotherapy to reduce the size of a tumor in combination with x-rays to detect metastasis. Also the presence of the tumor in a horseshoe kidney as well as the lung lesions, both are additional factors that necessitate the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy [19]. Researchers have believed teratoid Wilms tumors are resistant to chemotherapy, and upfront resection is preferred [20,21,22]. Because most of our patient’s tumor was blastemal, they responded considerably well to chemotherapy and regressed. However, as studies had suggested, the teratoid part of the tumor did not respond to chemotherapy at all.

The occurrence of renal anomalies associated with a malignancy might be more frequent in the clinical environment. There are numerous differential diagnoses for renal tumors and masses, but the possibility of exceptional anomalies should not be denied, and clinicians should be prepared for these occasions. The report of rare cases like this may encourage practitioners to detect renal tumors at an early stage in children diagnosed antenatally with horseshoe kidney. Although studies propose that chemotherapy has a trivial effect on teratoid Wilms tumors, it is essential to evaluate the tumor for any possibility of regression in non-teratoid regions before proceeding to upfront tumoral resection.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NWTS-5:

-

National Wilms Tumor Study-5

- SIOP:

-

International Society of Paediatric Oncology

- WT1:

-

Wilms tumor

References

Bhandarkar KP, Kittur DH, Patil SV, Jadhav SS. Horseshoe kidney and associated anomalies: single institutional review of 20 cases. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2018;15(2):104–7.

Hamilton TE, Shamberger RC. Wilms tumor: recent advances in clinical care and biology. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012;21(1):15–20.

Lee SH, Bae MH, Choi SH, Lee JS, Cho YS, Joo KJ, Kwon CH, Park HJ. Wilms’ tumor in a horseshoe kidney. Korean J Urol. 2012;53(8):577–80.

Choi DJ, Wallace EC, Fraire AE, Baiyee D. Best cases from the AFIP: intrarenal teratoma. Radiographics. 2005;25(2):481–5.

Weizer AZ, Silverstein AD, Auge BK, et al. Determining the incidence of horseshoe kidney from radiographic data at a single institution. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1722–6.

Farouk AG, Ibrahim HA, Farate A, Wabada S, Mustapha MG. Advanced-stage Wilms tumor arising in a horseshoe kidney of a 9-year-old child: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):470.

Luu DT, Duc NM, Tra My TT, Bang LV, Lien Bang MT, Van ND. Wilms’ tumor in horseshoe kidney. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2021;11(2):124–8.

Cascio S, Sweeney B, Granata C, Piaggio G, Jasonni V, Puri P, et al. Vesicoureteral reflux and ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children with horseshoe kidney: Treatment and outcome. J Urol. 2002;167(6):2566–8.

Neville H, Ritchey ML, Shamberger RC, Haase G, Perlman S, Yoshioka T. The occurrence of Wilms tumor in horseshoe kidneys: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group (NWTSG). J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(8):1134–7.

Beckwith JB, Kiviat NB, Bonadio JF. Nephrogenic rests, nephroblastomatosis, and the pathogenesis of Wilms’ tumor. Pediatr Pathol. 1990;10(1–2):1–36.

Treger TD, Chowdhury T, Pritchard-Jones K, Behjati S. The genetic changes of Wilms tumour. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(4):240–51.

Kim S, Chung DH. Pediatric solid malignancies: neuroblastoma and Wilms’ tumor. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86(2):469-xi 11p13. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95(22):13068-13072.

Miles C, Elgar G, Coles E, Kleinjan DJ, van Heyningen V, Hastie N. Complete sequencing of the Fugu WAGR region from WT1 to PAX6: dramatic compaction and conservation of synteny with human chromosome. pnas. 1998;95(22):13068–72.

Riccardi VM, Sujansky E, Smith AC, Francke U. Chromosomal imbalance in the Aniridia-Wilms’ tumor association: 11p interstitial deletion. Pediatrics. 1978;61(4):604–10.

Pappis CH, Moussatos GH, Constantinides CG, Kairis M. Bilateral nephroblastoma in a horseshoe kidney. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14(4):483–4.

Myers JB, Dall’Era J, Odom LF, McGavran L, Lovell MA, Furness P 3rd. Teratoid Wilms’ tumor, an important variant of nephroblastoma. J Pediatr Urol. 2007;3(4):282–6.

Beckwith JB. Wilms’ tumor and other renal tumors of childhood: a selective review from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Pathology Center. Hum Pathol. 1983;14(6):481–92.

Magee JF, Ansari S, McFadden DE, Dimmick J. Teratoid Wilms’ tumour: a report of two cases. Histopathology. 1992;20(5):427–31.

Bhatnagar S. Management of Wilms’ tumor: NWTS vs SIOP. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14(1):6–14.

Gupta R, Sharma A, Arora R, Dinda AK. Stroma-predominant Wilms tumor with teratoid features: report of a rare case and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25(3):293–5.

Vujanić GM, Sandstedt B, Harms D, et al. Revised International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) working classification of renal tumors of childhood. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(2):79–82.

Inoue M, Uchida K, Kohei O, et al. Teratoid Wilms’ tumor: a case report with literature review. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(10):1759–63.

Funding

No funding was obtained for the writing and publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NM, AE and AA managed the care of the patient during the inpatient stay. GB performed the successful technique outlined in this case report. PA, AG and KG provided revisions. KG wrote all versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NA for this retrospective publication of a case report.

Consent for publication

The patient’s parents have given their written informed consent to publish this case (including publication of images).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mortazavi, N., Eshghi, A., Ahmadvand, A. et al. Horseshoe kidney with teratoid type of Wilms tumor: a rare case report. BMC Nephrol 25, 267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-024-03709-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-024-03709-5