Abstract

Background

Infectious endocarditis (IE) is an infectious disease caused by direct invasion of the heart valve, endocardium, or adjacent large artery endocardium by pathogenic microorganisms. Despite its relatively low incidence, it has a poor prognosis and a high mortality. Intracranial infectious aneurysms (IIA) and ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (RSVA) are rare complications of IE.

Case presentation

We report a young male patient with symptoms of respiratory tract infection, heart murmurs and other symptoms and signs. The patient also had kidney function impairment and poor response to symptomatic therapy. Blood culture was negative, but echocardiography was positive, which met the diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis. Moreover, an echocardiography showed a ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm with a ventricular septal defect. Finally, secondary rupture of an IIA with multiple organ damage led to a poor clinical outcome.

Conclusion

Therefore, in the clinical setting, for young patients with unexplained fever, chest pain, or palpitations, we need to be highly vigilant, considering the possibility of infective endocarditis and promptly performing blood culture, echocardiography, cerebrovascular imaging and so on, in order to facilitate early proper diagnosis and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infectious endocarditis (IE) is an infectious disease caused by direct invasion of the heart valve, endocardium, or adjacent large artery endocardium by pathogenic microorganisms [1]. Despite its relatively low incidence, it has a poor prognosis and a high mortality. Intracranial infectious aneurysms (IIA) and ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (RSVA) are rare complications of IE, and mortality is extremely high once ruptured [2, 3]. This study reports a case of IE combined with intracranial aneurysm re-rupture and aortic sinus tumor rupture. This case is relatively rare and should be considered for clinical diagnosis.

Case presentation

The authors present a case of a 23-year-old male patient, previously healthy, until one week before the admission, when he started to develop persistent cough, expectoration and chest pain, treated conservatively. Three days before admission, the patient’s condition worsened, with edema of the lower limbs, cold extremities, afternoon fever, (body temperature reached 40℃), and occasional palpitation. The patient was previously healthy and denied a history of surgery, trauma, and family genetic history.

After the patient was hospitalized, chest CT showed pulmonary inflammation in both lungs, a slightly larger heart shadow, bilateral pleural thickening and little pleural effusion (Fig. 1g). Laboratory tests revealed a CRP level > 160 mg/L, a PCT level of 1.04 ng/ml, a high WBC and NEUT and low haemoglobin. Routine urine analysis revealed increased red blood cell count and the presence of urine protein.

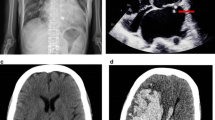

After piperacillin and tazobactam sodium and other symptomatic treatment, the patient’s symptoms did not improve significantly. Five days later, the patient’s symptoms of chest pain, palpitations and edema in both lower limbs worsened. ECG showed an increased ventricular rate and significant left ventricular high voltage. High sensitive troponin (100pg/ml) and myocardial zymogram examination revealed myocardial injury. B-type pronatriuretic peptide elevated significantly. Echocardiography revealed a dilated aortic sinus with the presence of an aortic valve vegetation and complicated with moderate to severe aortic regurgitation and an abnormal left-to-right shunt between the right aortic coronary sinus and the right ventricle, as well as a dilated left ventricle with reduced ejection fraction (Fig. 1a, b, c and d). Considering the possibility of IE and both negative blood cultures, the patient’s antibiotic was upgraded to Biapenem.

However, 7 days after admission, the patient got sudden headache, slurred speech, nausea and vomiting. The patient is conscious and has dysarthria. Both pupils are equal in size and roundness, and are sensitive to light reflection. The patient had no evidence of facial palsy or tongue deviation. Muscle tone and tendon reflexes were normal. There was a right hemiparesis graded 4 + in Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. Babinski sign was not elicited. Nuchal rigidity was present. Cranial CT suggested subarachnoid hemorrhage that was located in the left fissure cistern, ambient cistern and part of the left sulcus. Head and neck combined computer tomography angiography (CTA) revealed an aneurysm in the M2 segment of the left middle cerebral artery, measuring 3.1 mm×2.2 mm (Fig. 1e). The GSC coma scale score was 15 and the modified Fisher scale score was 3. The patient was advised to perform cerebral digital subtraction angiography (DSA) to clarify the intracranial aneurysm condition.

10 min before performing DSA, the patient suddenly became unconscious with conjugate eye deviation to the right, motor agitation, increased tone in the four limbs and sweating. The Glasgow coma score decreased to 2T (1 + T + 1). Physical examination revealed deep coma, bilateral dilated pupils with loss of light reflection and the presence of nuchal rigidity. Babinski sign was elicited. There was an audible and continuous murmur in the precordium as well as pistol shot sounds in both the brachial artery and femoral artery. Repeated cranial CT showed hematoma formation in the left basal ganglia (Fig. 1h). Re-rupture of the intracranial aneurysm was considered. Cerebral DSA revealed an aneurysm distal to the M2 segment of the left middle cerebral artery with a diameter of approximately 6.0 mm×6.5 mm, which had irregular morphology and significant enlargement (Fig. 1f). The comprehensive condition was considered an IIA. The patient’s carer declined further endovascular interventional or surgical treatment and requested for discharge. The patient died three days later.

(a)Echocardiography showing hypoecho attachment to the aortic valve (vegetation). (b) Continuous wave doppler showing a continuous flow between right coronary sinus and right ventricle, compatible with left-to-right shunt. (c) Rupture of a right coronary sinus aneurysm and interventricular septal defect. (d) Color doppler showing an image of the left to right shunt. (e) Head and neck CTA showing an M2 segment aneurysm in the left middle cerebral artery with a size of 3.1 mm×2.2 mm. (f) DSA image showing a distal aneurysm in the M2 segment of the left middle cerebral artery with a diameter of approximately 6.0 mm×6.5 mm. (g) First rupture of the IIA forming as showing by a CT image of subarachnoid hemorrhage.(h) Another rupture of the IIA was observed via a CT image of the ICH

Discussion

The most common manifestation of patients with IE is fever, which is often accompanied by chills, loss of appetite and emaciation, followed by heart murmur. In addition, vascular and immunological abnormalities, brain, lung, spleen and other organ ischemia symptoms are also manifestations of IE. Clinical manifestations of IE are very different and not specific. The diagnosis of IE relies on the modified Duke diagnostic criteria [4]. In the case presented, the patient started with prodromal symptoms of respiratory infection, such as cough and expectoration, and later developed signs and symptoms of systemic disease, such as repeated high fever, cardiac auscultation murmur, hematuria, urinary protein and kidney function impairment. The effect was poor after symptomatic treatment. Although the patient had negative blood cultures, he had an echocardiography showing the presence of aortic vegetation, body temperature > 38℃, aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis. The above symptoms can be clearly diagnosed as IE, which were consistent with 1major criterion and 3 minor criteria of the modified Duke diagnostic criteria. The cause of the patient’s illness cannot be determined. Echocardiography shows that the patient has a ventricular septal defect, but the patient’s accompanying family denies any history of congenital heart disease, cardiac surgery, intravenous drug abuse, or diabetes. Based on the results of autoimmune antibody tests, tumor markers, imaging studies, etc., the possibility of tumors or immune factors is relatively small. It is considered that the patient may lean towards rheumatic heart disease or congenital heart disease [5]. A study showed 16.8% of patients with IE were culture negative. Patients with culture negative IE are on average younger and have higher mortality due to the inability to identify the pathogen [6]. Regarding the reasons for negative blood cultures, we consider the following five points: Firstly, prior antibiotic treatment for nearly a week may have inhibited microorganism growth. Secondly, other slow-growing pathogens such as Bartonella species, Brucella species, Coxiella burnetii, and the HACEK family could be supporting the infection. Thirdly, non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis caused by malignant tumors can be excluded due to the patient’s young age and absence of tumor-related findings. Fourthly, common serologic tests may lack sensitivity and specificity in accurately diagnosing certain strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus viridans. Finally, poor collection of blood samples cannot be ruled out as a possibility. We speculate that antibiotics might have a higher likelihood of causing negative blood cultures [7].

IE patients may develop neurological complications. The neurological complications can be divided into cerebrovascular ischaemic events, intracranial haemorrhage, infectious aneurysms, infectious lesions, or epilepsy [8]. Intracranial infectious aneurysm (IIA) is most frequently secondary to IE and are mostly caused by the shedding of fragile microbial emboli on the heart valve or prosthesis, hematogenous spread of pathogenic microorganisms or direct invasion of cerebral arteries by intracranial infection focus. A study showed that 2 − 10% of patients with IE experience IIA [9]. IIA is a rare infectious vascular lesion of the nervous system, and it accounts for 0.7 − 5.4% of intracranial aneurysms [10]. IIA patients are often recognized after rupture. A review revealed that the mortality of IIA rupture was approximately 30% [11]. Kannoth and Thomas proposed the diagnostic criteria and procedures for IIA [12]. This young patient had a clear history of IE and fever before admission. Cerebrovascular imaging revealed middle cerebral artery distal aneurysm and aneurysm morphology changes, and a cranial CT scan revealed subarachnoid intracranial aneurysm hemorrhage and intracranial hemorrhage. The patient met the IIA diagnostic criteria, which can clarify clinical diagnosis. The duration of IIA rupture is approximately 2–5 weeks after the onset of IE, and some studies have shown that massive bleeding events occur even after 1 week of antimicrobial treatment [13]. Therefore, close monitoring with continuous neurovascular imaging within 2 weeks after the diagnosis of IIA, including MRA, CTA and DSA [14]. Aneurysm rupture again may be the main factors leading to poor outcomes. Several studies have shown that 5.8-19.3% of patients experience aneurysm rebleeding after initial rupture, and the rehemorrhage mortality is as high as 46.2 -80%, among which the immediate mortality is as high as approximately 50%. This patient suffered from the intracranial aneurysm re-ruptured within 24 h, while the mortality was nearly 60% [15, 16]. There is a lack of high-quality evidence-based recommendations for IIA treatment, including conservative treatment with antibiotics, endovascular treatment, aneuryliectomy, and surgical clipping [17]. Due to the wide width or absence of the neck of the IIA and the vascular vulnerability of the parent artery and aneurysm wall, surgical clipping is more difficult, and frequently surgery requires the sacrifice of the parent artery, which may cause serious neurological injury. Endovascular intervention is relatively safe, but only 24% of patients can retain the parent artery. Although intracranial stents can preserve vascular integrity, they are used only for proximal lesions, and few reports on these methods exist [2].

Echocardiography revealed this patient also had RSVA(ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm) with ventricular septal defect. RSVA is a rare heart disease, with an incidence of approximately 0.09%. The weak sinus wall breaks up with the impact of the pulsatile high flow bundle in the aorta, and produces a series of haemodynamic changes. RSVA mostly occurs in young and middle-aged people, and is often combined with ventricular septal defects and aortic valve lesions [3].Congenital RSVA occurs in the right coronary sinus. The cause of acquired formation are endocarditis, atherosclerosis, syphilis and trauma [18]. The symptoms of aortic sinus tumors are not obvious without rupture. The symptoms after rupture include dyspnea, palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, cough and inability to lie supine at night. The signs after rupture are enlarged heart boundaries, audiblility in the auscultation area of the aortic valve and rough continuous murmur. The clinical diagnosis is often made by echocardiography which reveals the local sinus wall of the aorta, and the left-to-right shunt signal, mainly in diastolic period, at the rupture site. If there is a ventricular septal defect, a persistent left-to-right shunt signal can be observed [19]. The patient had congenital ventricular septal defects and obvious symptoms, such as chest pain, dyspnoea, obvious murmur in the aortic auscultation area, shooting sounds and echocardiography results, which were in line with the above diagnosis and could be diagnosed as RSVA. RSVA easily leads to severe congestive heart failure, which is often treated by percutaneous transcatheter occlusion or surgical closure surgery [20].

Conclusions

In this case, due to IE, the IAA ruptured again and RSVA, accompanied by multiple organ damage, resulting in poor clinical outcome. Therefore, patients with unexplained fever, chest pain and palpitations, a high degree of vigilance should be paid more attention to the possibility of IE. Bloodculture, echocardiography are important means to diagnose IE. We need to perform these examinations timely to clarify the diagnosis as soon as possible. Although IIA rebleeding with RSVA is rare, the disability and mortality are very high, which brings great challenges to clinical treatment. We need to pay close attention to this complication. For patients with confirmed IE, we should attach great importance to their neurological symptoms and conduct timely cerebrovascular imaging screening to avoid adverse consequences. This case provides an important clinical reference that reminds us to strengthen the understanding of IE and to constantly accumulate experience to better diagnose and treat this disease.

Data availability

The datasets used or analysed during the present case reports are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- CTA:

-

Computer Tomography Angiography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- MRA:

-

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

- DSA:

-

Digitalsubtraction

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- IE:

-

Infectious Endocarditis

- RSVA:

-

Ruptured Sinus of Valsalva Aneurysm

- IIA:

-

Intracranial Infectious Aneurysms

- ICH:

-

Intra-Cerebral Hemorrhage

- CRP:

-

C-Reactive Protein

- PCT:

-

Procalcitonin

- WBC:

-

White Biood Count

- NEUT:

-

Neutrophil Count

References

Hubers SA, DeSimone DC, Gersh BJ, Anavekar NS. Infective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(5):982 – 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.12.008

Champeaux C, Walker N, Derwin J, Grivas A. Successful delayed coiling of a ruptured growing distal posterior cerebral artery mycotic aneurysm. Neurochirurgie. 2017;63(1):17–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2016.10.005.

Ayati A, Toofaninejad N, Hosseinsabet A, Mohammadi F, Hosseini K. Transcatheter closure of a ruptured sinus of valsalva: a systematic review of the literature. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1227761. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1227761.

Fowler VG, Durack DT, Selton-Suty C, Athan E, Bayer AS, Chamis AL, et al. The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious diseases Criteria for Infective endocarditis: updating the modified Duke Criteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(4):518–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad271.

Nappi F, Spadaccio C, Mihos C. Infective endocarditis in the 21st century. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(23):1620. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20.

Kong WKF, Salsano A, Giacobbe DR, Popescu BA, Laroche C, Duval X, et al. Outcomes of culture-negative vs. culture-positive infective endocarditis: the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO registry. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(29):2770–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac307.

Nappi F. Native infective endocarditis: a state-of-the-art-review. Microorganisms. 2024;12(7):1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12071481. Published 2024 Jul 19.

Sotero FD, Rosário M, Fonseca AC, Ferro JM. Neurological complications of infective endocarditis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19(5):23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-019-0935-x.

Ducruet AF, Hickman ZL, Zacharia BE, Narula R, Grobelny BT, Gorski J, et al. Intracranial infectious aneurysms: a comprehensive review. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;33(1):37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-009-0233-1.

Ando K, Hasegawa H, Kikuchi B, Saito S, On J, Shibuya K, et al. Treatment strategies for infectious intracranial aneurysms: report of three cases and review of the literature. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2019;59(9):344–50. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.oa.2019-0051.

Kannoth S, Thomas SV. Intracranial microbial aneurysm (infectious aneurysm): current options for diagnosis and management. Neurocrit Care. 2009;11(1):120–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-009-9208-x.

Kannoth S, Thomas SV, Nair S, Sarma PS. Proposed diagnostic criteria for intracranial infectious aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(8):943–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.131664.

García-Cabrera E, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Almirante B, Ivanova-Georgieva R, Noureddine M, Plata A, et al. Neurological complications of infective endocarditis: risk factors, outcome, and impact of cardiac surgery: a multicenter observational study. Circulation. 2013;127(23):2272–84. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000813.

Nunes RH, Corrêa DG, Pacheco FT, Fonseca APA, Hygino da Cruz LC Jr., da, Rocha AJ. Neuroimaging of Infectious Vasculopathy. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2024;34(1):93–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nic.2023.07.006

Van Donkelaar CE, Bakker NA, Veeger NJ, Uyttenboogaart M, Metzemaekers JD, Luijckx GJ, et al. Predictive factors for rebleeding after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: rebleeding Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Study. Stroke. 2015;46(8):2100–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010037.

Zhao B, Yang H, Zheng K, Li Z, Xiong Y, Tan X, et al. Predictors of good functional outcomes and mortality in patients with severe rebleeding after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;144:28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.02.042.

Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, Bonaros N, Brida M, Burri H, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(39):3948–4042. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad193.

Jin Y, Han XM, Wang HS, Wang ZW, Fang MH, Yu Y, et al. Coexisting ventricular septal defect affects the features of ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysms. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(3):257–61. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.3.15842.

Cheng TO, Yang YL, Xie MX, Wang XF, Dong NG, Su W, et al. Echocardiographic diagnosis of sinus of Valsalva aneurysm: a 17-year (1995–2012) experience of 212 surgically treated patients from one single medical center in China. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173(1):33–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.02.003.

Kuriakose EM, Bhatla P, McElhinney DB. Comparison of reported outcomes with percutaneous versus surgical closure of ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(3):392–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.11.013.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZS wrote the manuscript, performed the literature search and collected the data. XX performed the data interpretation. ZL conceived of the ideas and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics from Henan Province Hospital of TCM Committee.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Z., Xu, X. & Liu, Z. Infectious endocarditis complicated with intracranial infected aneurysm rupture and sinus of valsalva aneurysm rupture. BMC Neurol 24, 372 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03870-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03870-2