Abstract

Background

Stillbirth rates remain a global priority and in Australia, progress has been slow. Risk factors of stillbirth are unique in Australia due to large areas of remoteness, and limited resource availability affecting the ability to identify areas of need and prevalence of factors associated with stillbirth. This retrospective cohort study describes lifestyle and sociodemographic factors associated with stillbirth in South Australia (SA), between 1998 and 2016.

Methods

All restigered births in SA between 1998 ad 2016 are included. The primary outcome was stillbirth (birth with no signs of life ≥ 20 weeks gestation or ≥ 400 g if gestational age was not reported). Associations between stillbirth and lifestyle and sociodemographic factors were evaluated using multivariable logistic regression and described using adjusted odds ratios (aORs).

Results

A total of 363,959 births (including 1767 stillbirths) were included. Inadequate antenatal care access (assessed against the Australian Pregnancy Care Guidelines) was associated with the highest odds of stillbirth (aOR 3.93, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.41–4.52). Other factors with important associations with stillbirth were plant/machine operation (aOR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.16–2.45), birthing person age ≥ 40 years (aOR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.50–2.45), partner reported as a pensioner (aOR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.12–2.99), Asian country of birth (aOR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.19–2.10) and Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander status (aOR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.20–1.88). The odds of stillbirth were increased in regional/remote areas in association with inadequate antenatal care (aOR, 4.64; 95% CI, 2.98–7.23), birthing age 35–40 years (aOR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.02–3.64), Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status (aOR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.12–3.21), paternal occupations: tradesperson (aOR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.17–6.16) and unemployment (aOR, 4.06; 95% CI, 1.41–11.73).

Conclusion

Factors identified as independently associated with stillbirth odds include factors that could be addressed through timely access to adequate antenatal care and are likely relevant throughout Australia. The identified factors should be the target of stillbirth prevention strategies/efforts. SThe stillbirth rate in Australia is a national concern. Reducing preventable stillbirths remains a global priority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Globally, more than 2.64 million babies are stillborn annually, with the highest rates occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1, 2]. In high-income countries (HICs), preventable stillbirths continue to be of concern, with slow progress towards global targets for rate reduction. To address this issue, the Australian government appointed a Senate Select Committee on Stillbirth Research and Education in 2018 [3]. Their report revealed that Australia had ‘slipped’ in its progress to reduce stillbirth rates in line with targets compared with other HICs. It also demonstrated that babies born to mothers living remotely were more likely to be stillborn than babies born in major cities [4]. In 2020, Women and Birth published a series focused on stillbirth in Australia and identified the national action required to decrease rates [5,6,7,8,9]. Rumbold et al. [9] highlighted the impact of inequity on stillbirth rates within select Australian populations, noting particular concern within communities experiencing isolation and socioeconomic disadvantage [9]. Numerous risk factors in disadvantaged communities contribute to the widening gap in health inequality, further hindering stillbirth prevention [10]. This research aims to identify lifestyle and sociodemographic risk factors for stillbirth in South Australia (SA) geographically and to explore these risks according to remoteness.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective state-wide observational cohort study using the SA perinatal outcomes dataset, including all births from 1998 to 2016 (cohort one). The dataset contains pregnancy outcomes categorised as live birth or stillbirth. The data were obtained anonymously, with all identifying fields removed prior to their provision for research purposes. The study concept, acceptability, methods and interim analysis were presented, reviewed, and approved by the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Stillbirth Indigenous Advisory Committee at two separate timepoints. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by local SA Indigenous researchers and senior health care advisors prior to submission.

Materials

In SA, all births are reported by midwives, birth attendants and obstetricians in standardised supplementary birth records. The SA Perinatal Outcomes Unit integrates continuous validation of the dataset by comparing data collected from the supplementary birth records to electronic hospital records at the time of coding. Sociodemographic characteristics and pregnancy and birth outcome data were recorded. Due to the later introduction of BMI to the data collection, analyses involving BMI were restricted to the years 2007–2016 (cohort two). Terminations of pregnancy were excluded.

Definitions and outcomes

Variable definitions and time periods are provided in Table 1. Information for all births (live or stillborn) ≥ 20 weeks gestational age (GA) of ≥ 400 g at birth are reported. The primary outcome, stillbirth, was defined in line with the standard Australian Institute of Health and Wellbeing definition as the birth of a baby showing no signs of life at ≥ 20 weeks’ completed GA, or ≥ 400 g birthweight where no GA is provided.

Rural and remote living at birth status was based on statistical areas level 3 (SA3) data associated with each birth. Australia Bureau of Statistics modified Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) score average for each SA3 area compiled from SA2 area ARIA + scores. The areas were classified as: major cities, inner regional areas, outer regional areas, or remote/very remote areas. When exposure data or variable data were missing, individual births were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Variables were categorised as outlined in Table 1. Categories with < 10 stillbirths per group were reported as ‘< 10’, and crude odds ratios (ORs) concealed. Within multivariable analysis where categories had fewer than five stillbirths, analyses are reported as ‘< 5’. Logistic regression was performed using the statistical software STATA 16 IC [11] to determine associations between potential risk factors and stillbirth, described using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Unadjusted and adjusted models were considered, with adjustments made for variables that demonstrated significance during univariate analysis (p < 0.001). For each risk factor, adjustment variables included year of birth, adequate antenatal care (ANC) access (adjusted for GA at birth), marital status, ethnicity, smoking status, parity, remote/rural status, age, previous stillbirth, medical conditions (preexisting diabetes, hypertension, anaemia), plurality, interpregnancy interval, insurance status, and obstetric complications (gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, antepartum haemorrhage [APH]). The cohort was stratified by residential remoteness, and the analysis was repeated using the same adjustment variables (excluding rural/remote status). Factors demonstrating the strongest association with stillbirth odds were further explored to calculate SA-specific population attributable fractions [12] and annual attributable stillbirths per factor (n). The analysis was repeated for cohort two, which was additionally adjusted for BMI (Tables 4 and 5).

Results

Data were available for 363,933 births in SA including 1,767 stillborn babies following exclusions (Table 2). Birthing people were predominantly Australian born (81%) with 86% of Australian born people identifying as Caucasian. The majority (71%) lived in major cities, followed by inner regional areas (14%), outer regional areas (8%) and remote or very remote areas (6%). During pregnancy, 13.5% of birthing people access less than the recommended number of ANC visits (Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care recommends that nulliparous women have a minimum of 10 and multiparous women have a minimum of 7). Most birthing people were nonsmokers (78%) and gave birth in the Australian public health care system (70%) (Table 2). Cohort two included 201,315 births (918 stillborn babies) between 2007 and 2016.

The stillbirth rate in SA over the study period was 4.85/1000 births. Stillbirth rates were highest for birthing people who had inadequate ANC access (13.78/1000 births) and those who reported that they (8.78/1000 births) or their non-birthing partner were a ‘pensioner’ (10.21/1000 births). Stillbirths were high among ‘unemployed’ individuals and ‘plant or machine operators’ (8.15 and 7.97/1000 births, respectively), those aged less than 19 or over 40 (7.51 and 7.71/1000 births, respectively), and those who were unmarried (7.63/1000 births) or smoked (6.20/1000 births). Stratification by remoteness status suggested that rates of stillbirth differed minimally by remoteness classification (Table 3).

Adequacy of antenatal care access (ANC)

Crude analysis demonstrated a fourfold increase in stillbirth odds for birthing people who received inadequate ANC compared with those who received adequate ANC (Table 2). This increased odds of stillbirth following inadequate ANC access was observed across all areas of residence (Table 3). Adjusted analysis demonstrated that birthing people in SA who experienced inadequate versus adequate ANC access had fivefold greater odds of stillbirth (inner region: aOR 5.56; 95% CI 3.91–7.92; remote/very remote region: aOR 4.64; 95% CI 2.98–7.23).

Parental occupation

Crude analysis indicated that several occupations were associated with stillbirth. Through multivariable analysis, birthing people who worked as plant/machine operators had almost double the odds of stillbirth versus professionals (aOR 1.99; 95% CI 1.16–3.43). Compared with professionals, unemployed birthing people also had increased odds of stillbirth (aOR 1.34; 95% CI 1.01–1.79). No clear differences were noted in the area stratified analysis considering unemployment (compared with major cities, outer regional areas: aOR 1.59; 95% CI 0.63–4.03, remote/very remote areas: aOR 1.35; 95% CI 0.54–3.39).

Unemployed non-birthing parent status (aOR 1.33; 95% CI 1.01–1.76) and pensioner status (aOR 1.83; 95% CI 1.12–2.99) versus professional status were associated with increased odds of stillbirth. Non-birthing parent tradeperson status (aOR 1.69; 95% CI 1.17–6.16) and unemployment (aOR 4.06; 95% CI 1.41–11.73) was independently associated with stillbirth within remote/very remote areas of SA (Table 3).

Birthing persons’ country of birth

Crude analysis demonstrated increased odds of stillbirth for birthing people born in Southern Asia, the Middle East/North Africa, and Africa versus Australia (Table 2). Increased odds of stillbirth were shown for birthing people from Southern Asia (versus Australia) (aOR 1.58; 95% CI 1.19–2.10). This was mirrored for South Asian-born birthing people residing in major cities (Table 3). Crude analysis revealed greater stillbirth odds for birthing people born in Middle Eastern/North African countries; however, this increase was attenuated in multivariable analyses. Similar results were shown for birthing people from African countries (64% increased odds of stillbirth) (versus Australia); however, the odds were attenuated in the multivariate analysis (aOR 0.82; 95% CI 0.29–2.27). The odds of stillbirth did not increase for any of the other countries in which the birthing people were born compared with those for which the birthing people were born in Australia.

Birthing persons’ ethnicity

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status (versus Caucasian status) was shown to increase stillbirth odds through crude and adjusted analyses (cOR 2.55; 95% CI 2.11–3.08, and aOR 1.50; 95% CI 1.20–1.88). Stratification by place of residence revealed that the odds of stillbirth for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander versus Caucasian people were almost double within inner regional (aOR 1.91; 95% CI 1.06–3.46) and remote/very remote areas (aOR 1.90; 95% CI 1.12–3.21). Self-reported Asian ethnicity (versus Caucasian status) did not show an increase in stillbirth odds (aOR 1.12; 95% CI 0.93–1.35). Stratification by areas of remoteness could not be performed due to small case numbers per subgroup.

BMI (cohort two)

Similar to cohort one, analyses of cohort two demonstrated increased odds of stillbirth with inadequate ANC access, particular parental occupations, and certain birthing person’s country of birth and ethnicity (Table 4). Birthing person BMI was associated with marginally increased odds of stillbirth for BMI’s between 35 and 39 at the first antenatal appointment (Table 5). These findings were mirrored through remoteness stratification analysis. The odds of stillbirth were not significant for morbidly obese birthing people according to the analysis, possibly reflecting an underpowered sample size in this category. Through models adjusted for BMI, the associations between Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander ethnicity and stillbirth odds decreased, eliminating this factor’s independent association with stillbirth.

Population attributable fractions (PAFs) (Table 6)

Factors with the strongest independent associations with stillbirth odds were selected to determine PAFs (Table 6). The PAF enabled examination of the direct percentage of stillbirths attributed to each risk factor within the population according to the populational prevalence. The factors with the greatest impacts on stillbirth rates in SA were inadequate ANC access (PAF: 27.65%) and birthing person age > 35 years (PAF: 6.32%). The PAFs for smoking or residing in outer regional/remote or very remote areas were 3.31% and 3.24%, respectively.

Discussion

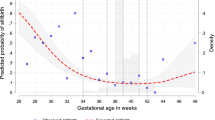

Adequate ANC access in Australia has been highlighted as a marker of inequity between areas of remoteness and major cities [3] and is well established as the best means to ensure a healthy pregnancy and effective preventative care for poor pregnancy outcomes. Our results suggest that inadequate ANC access (as per the Australian pregnancy care guidelines [13]) is strongly associated with increased odds of stillbirth. The recommended number of ANC visits is 10 for first pregnancies and seven for subsequent uncomplicated pregnancies [13]. PAF calculations indicated that if all recommended appointments were accessible to all birthing people, 437 stillbirths could have been prevented over this study period, equating to an average of 24 stillbirths per year. Previous research examining the impact of ANC on stillbirths has revealed a U-shaped curve and has suggested that 14 visits is optimal to minimise risk [14]. Globally, there are notable variations in the minimum number of visits recommended; German studies suggest 12 [15], USA, 11 [16], and Canada [17, 18]. Strategies to encourage improved ANC access, such as culturally safe care models, and addressing travel and financial barriers to access, alongside further consideration of an increase in the minimum number of recommended ANC visits in Australia, should constitute part of stillbirth prevention efforts.

Remote and rural status has previously been shown to have an independent association with intrapartum stillbirth in remote Western Australia due to a lack of access to high-level care during labour, although Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women were excluded from these findings because the main outcome focused on migrant women in Western Australia [19]. Comparable results have been shown in studies examining the impact of regional and remote living on stillbirth rates in Australia [20, 21], although the findings were limited by cohort size and limited confounder adjustment. Our analysis revealed marginally greater odds of stillbirth within regional areas (i.e., the outer and inner regional areas), and for birthing people who smoked during pregnancy, who were unmarried or of advanced age (over 35 years). Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander birthing people were at increased risk of stillbirth in inner and outer regional areas. These findings further highlight the need for increased preventative care for those living in regional and remote areas.

There are mixed findings regarding the association between Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander People and stillbirth odds. Some have reported increased odds of stillbirth, while others have reported equivalence [22, 23]. Our study suggested that Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander birthing people are at risk of 21 stillbirths per year in SA. Compared with Caucasian birthing people, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander birthing people residing in inner regional and remote/very remote areas experience greater stillbirth odds than their city-dwelling counterparts. An analysis incorporating BMI into models of adjustment diminished this association, indicating that there was no independent association with stillbirth odds and that strategies to address BMI may be key. This may implicate a combined lack of culturally safe care models, limited birthing on country services, and poorly resourced ANC in regional and remote areas of SA. Cultural safety and birthing on country training of health care professionals has been shown to improve access for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander families, including trauma-informed care [24].

South Asian ethnicity has previously been shown to have an independent association with stillbirth odds in HIC populations globally [19, 25,26,27,28,29,30]. Analyses of stillbirth odds for birthing people of South Asian ethnicity have differed when country of birth has been used as a proxy for ethnicity in previous studies [19, 22, 26,27,28, 31] versus when self-reported ethnicity has been used [25, 29, 30]. Although country of birth is a commonly used proxy for ethnicity in some studies, there is a need for clear differentiation, as these are two different variables. One captures migration status, and the other captures self-reported ethnicity. The findings of this study demonstrate that South Asian (versus Australian) countries of birth are associated with stronger odds of stillbirth than self-reported Asian (versus Caucasian) ethnicity. Country of birth should be considered an independent factor when assessing the risk of stillbirth at the individual level.

Certain occupations and their associated exposures to chemicals or lifting and rotating shift work have previously been implicated as contributors to stillbirth in HICs [32,33,34]. To our knowledge, there has been no prior research examining associations between stillbirth and occupational groups within an entire population. The increased odds of stillbirth for plant- or machine-operating birthing people warrants attention. As does paternal unemployment and tradesperson status in remote and very remote areas. – both also associated with increased stillbirth odds in SA.

According to previous research on HICs, obesity consistently and independently increases stillbirth odds [31, 35, 36]. Our findings demonstrated that a BMI between 35 and 39 was associated with increased odds of stillbirth, but this was not observed when the BMI reached ≥ 40. This observation may be due to the low number of birthing people with a BMI ≥ 40, rendering the analysis underpowered. However, the absence of increased stillbirth odds for birthing people with a BMI ≥ 40 could be due to the different care pathways and tailored care and monitoring for this group. In SA, at their first antenatal appointment, this group is provided specific ANC programs focused on pregnancy risks and complications associated with morbid obesity [37].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study lie in the comprehensive and detailed measures for each birth, including the inclusion of parental occupational coding and ethnicity alongside country of birth. Factors included within this dataset are collected routinely for the entire study period without changes in the definition or classification of diseases. Due to the large number of stillbirths included in this study, analysis of many factors was possible, allowing meaningful and generalisable results. However, we acknowledge several limitations. The omission of BMI data collected prior to 2007 prevented the analysis of BMI across the study period. Cohort two encompasses BMI, but due to the smaller cohort size, comprehensive analysis was not possible. This study has the same limitations ubiquitous to research examining routinely collected perinatal data, which may not have been intended solely for research purposes. The lack of data concerning domestic assault, pollution, consanguinity, sleep position and drug/alcohol use leaves potential for residual bias due to unmeasured covariates. The current analysis does not account for the temporal changes in individual factors’ impacts over the course of the study period. The use of average ARIA + scores from SA2’s encompassed within each SA3 for remoteness status has the potential to result in misclassification of remoteness status for some populations within assigned categories.

Conclusion

Results demonstrate gaps in national- and state/territory-level analysis of stillbirth in Australia. Our findings indicate that inadequate ANC access is the greatest risk factor for stillbirth in SA, particularly remote SA. Complexities preventing engagement in care and poor attendance may reflect access to and acceptability of ANC programs across all facets of society. The evidence presented indicates that further research is needed to determine the required minimum number of ANC visits and provision of adequate access to the recommended number of ANC visits for all birthing people. This also needs to take into consideration the implications for current health care systems, especially in remote and regional areas. Omission of stratification by residential remoteness in previous research has masked disparities between marginalised groups within regions that are shown to have the highest rates of stillbirth. Through stratification, this research identifies that different factors are associated with increased stillbirth odds for people living in regional and remote areas of South Australia, than those living in major cities. The lack of evidence for these differences previously has meant that current pregnancy care guidelines and policies, although based on evidence at the national level, do not address differences that exist for health care providers serving populations in regional and remote areas, which are overlaid with finite access to resources. It is clear from our findings that the stillbirth odds for birthing people aged 35–40 years or with specific occupations differ according to residential remoteness classification. Through robust sub analysis incorporating comprehensive multivariable adjustment (including BMI), our findings demonstrate that birthing person Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status is not independently associated with stillbirth, and while there is no independent association, holistic and culturally safe care is essential. Improved access to care will aid in addressing factors that may be independently associated with and contributing to stillbirth rates within this population.

Data availability

The deidentified data analysed are not publicly available, but requests to the corresponding author for the data will be considered on a case-by-case basis in discussion with the South Australian Data Custodian. Requests may be referred to the South Australian Data Custodian to obtain approval.

References

Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Froen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1331–40.

Frøen JF, Cacciatore J, McClure EM, Kuti O, Jokhio AH, Islam M, et al. Stillbirths: why they matter. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1353–66.

Government A. Response to: the Senate Select Committee on Stillbirth Research and Education Report. Canberra; 2019.

Select Senate Committee on Stillbirth Research and Education. Select Committee on Stillbirth Research and Education Report. Stillbirth Research and Education. Parliment House, Canberra; 2018.

Boyle FM, Horey D, Dean JH, Loughnan S, Ludski K, Mead J, et al. Stillbirth in Australia 5: making respectful care after stillbirth a reality: the quest for parent-centred care. Women Birth: J Australian Coll Midwives. 2020;33(6):531–6.

Ellwood DA, Flenady VJ. Stillbirth in Australia 6: the future of stillbirth research and education. Women Birth: J Australian Coll Midwives. 2020;33(6):537–9.

Flenady VJ, Middleton P, Wallace EM, Morris J, Gordon A, Boyle FM et al. Stillbirth in Australia 1: The road to now: Two decades of stillbirth research and advocacy in Australia. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2020;33(6):506 – 13.

Gordon A, Chan L, Andrews C, Ludski K, Mead J, Brezler L, et al. Stillbirth in Australia 4: breaking the silence: amplifying Public Awareness of Stillbirth in Australia. Women Birth: J Australian Coll Midwives. 2020;33(6):526–30.

Rumbold AR, Yelland J, Stuart-Butler D, Forbes M, Due C, Boyle FM, et al. Stillbirth in Australia 3: addressing stillbirth inequities in Australia: steps towards a better future. Women Birth: J Australian Coll Midwives. 2020;33(6):520–5.

Fox H, Topp SM, Lindsay D, Callander E. Ethnic, socio-economic and geographic inequities in maternal health service coverage in Australia. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;36(6):2182–98.

StataCorp. In: Station C, editor. Stata Statistical Software: release 16. TX:: StataCorp LLC.; 2023.

Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Population attributable fraction. Br Med J (Online). 2018;360:k757.

Australian Government Department of Health. Clinical practice guidelines: pregnancy care. In: Australian Government Department of Health, editor. Canberra2020.

Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Scorza WE, Knuppel RA. Prenatal care and black-white fetal death disparity in the United States: heterogeneity by high-risk conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(3):483–9.

Reime B, Lindwedel U, Ertl KM, Jacob C, Schucking B, Wenzlaff P. Does underutilization of prenatal care explain the excess risk for stillbirth among women with migration background in Germany? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(11):1276–83.

Partridge S, Balayla J, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome: a retrospective analysis of 28,729,765 U.S. deliveries over 8 years. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(10):787–93.

Health Nexus Best Start Resource Centre. Ontario Prenatal Education 2022 [ https://www.ontarioprenataleducation.ca/routine-prenatal-care/.

Heaman MI, Martens PJ, Brownell MD, Chartier MJ, Derksen SA, Helewa ME. The Association of Inadequate and intensive prenatal care with maternal, fetal, and infant outcomes: a Population-based study in Manitoba, Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(7):947–59.

Mozooni M, Pennell CE, Preen DB. Healthcare factors associated with the risk of antepartum and intrapartum stillbirth in migrants in Western Australia (2005–2013): a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(3):e1003061.

Graham S, Pulver LRJ, Wang YA, Kelly PM, Laws PJ, Grayson N, et al. The urban-remote divide for indigenous perinatal outcomes. Med J Aust. 2007;186(10):509–12.

Robson S, Cameron CA, Roberts CL. Birth outcomes for teenage women in New South Wales, 1998–2003. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46(4):305–10.

Gordon A, Raynes-Greenow C, McGeechan K, Morris J, Jeffery H. Risk factors for antepartum stillbirth and the influence of maternal age in New South Wales Australia: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:12.

Hodyl NA, Grzeskowiak LE, Stark MJ, Scheil W, Clifton VL. The impact of Aboriginal status, cigarette smoking and smoking cessation on perinatal outcomes in South Australia. Med J Aust. 2014;201(5):274–8.

Kildea S, Hickey S, Barclay L, Kruske S, Nelson C, Sherwood J, et al. Implementing birthing on country services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families: RISE framework. Women Birth. 2019;32(5):466–75.

Balchin I, Whittaker JC, Patel R, Lamont RF, Steer PJ. Racial variation in the association between gestational age and perinatal mortality: prospective study. BMJ. 2007;334(7598):833–5.

Berman Y, Ibiebele I, Patterson JA, Randall D, Ford JB, Nippita T, et al. Rates of stillbirth by maternal region of birth and gestational age in New South Wales, Australia 2004–2015. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;60(3):425–32.

Davies-Tuck ML, Davey MA, Wallace EM. Maternal region of birth and stillbirth in Victoria, Australia 2000–2011: a retrospective cohort study of victorian perinatal data. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0178727.

Drysdale H, Ranasinha S, Kendall A, Knight M, Wallace EM. Ethnicity and the risk of late-pregnancy stillbirth. Med J Aust. 2012;197(5):278–81.

Heazell A, Li M, Budd J, Thompson J, Stacey T, Cronin RS, et al. Association between maternal sleep practices and late stillbirth - findings from a stillbirth case-control study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;125(2):254–62.

Ravelli AC, Tromp M, Eskes M, Droog JC, van der Post JA, Jager KJ, et al. Ethnic differences in stillbirth and early neonatal mortality in the Netherlands. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2011;65(8):696–701.

Gardosi J, Madurasinghe V, Williams M, Malik A, Francis A. Maternal and fetal risk factors for stillbirth: Population based study. Br Med J (Online). 2013;346(7893):f108.

Bonde JP, Jørgensen KT, Bonzini M, Palmer KT. Miscarriage and occupational activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis regarding shift work, working hours, lifting, standing, and physical workload. Scandinavian J Work Environ Health. 2013;39(4):325–34.

Mocevic E, Svendsen SW, Joørgensen KT, Frost P, Bonde JP. Occupational lifting, fetal death and preterm birth: findings from the Danish National Birth Cohort using a job exposure matrix. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90550.

Quansah R, Gissler M, Jaakkola JJ. Work as a nurse and a midwife and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a Finnish nationwide population-based study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(12):2071–6.

Tennant PW, Rankin J, Bell R. Maternal body mass index and the risk of fetal and infant death: a cohort study from the North of England. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1501–11.

Yao R, Park BY, Foster SE, Caughey AB. The association between gestational weight gain and risk of stillbirth: a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(10):638–44.

Government of South Australia. Obese Obstetric Woman - Management in South Australia 2019 Clinical Directive. SA Health.2019.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank SAHMRI Women and Kids for their support through this project, and also the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence for their financial support during the project. The University of Adelaide is also acknowledged for their financial support of the primary author during their higher degree by research of which this project forms a main component. Acknowledgement is also extended to the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence Indigenous Advisory Committee, and also the Aboriginal Communities and Families Health Research Alliance who assisted in guiding the objectives, and interpreting the results of this project.

Funding

No funding was received for this research outside of the primary authors affiliated organisations. Funding was granted for this project in the form of research training stipends (University of Adelaide) and PhD top-up scholarships (Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence) for A Bowman during the course of their higher degree by research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Software, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Interpretation of data TS: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing VF: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Analysis and interpretation of data MM: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review and editing ES: Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Interpretation of the data CL: Writing – review and editing, Analysis and interpretation of data DSB: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Analysis and interpretation of data KH: Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Analysis and interpretation of data PM: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Analysis and interpretation of data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted from the SA Department of Health and Wellbeing Committee (ID HREC19SAH13) on 11th of June 2019, and the Aboriginal Health Council of SA Human Research Ethics Committee (ID 04-19-816) on the 8th of May 2019. Participant consent was not an ethical requirement for this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bowman, A., Sullivan, T., Makrides, M. et al. Lifestyle and sociodemographic risk factors for stillbirth by region of residence in South Australia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24, 368 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06553-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06553-5