Abstract

Background

Organized breast cancer screening (BCS) programs are effective measures among women aged 50–69 for preventing the sixth cause of death in Germany. Although the implementation of the national screening program started in 2005, participation rates have not yet reached EU standards. It is unclear which and how sociodemographic factors are related to BCS attendance. This scoping review aims to identify sociodemographic inequalities in BCS attendance among 50-69-year-old women following the implementation of the Organized Screening Program in Germany.

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines, we searched the Web of Science, Scopus, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL following the PCC (Population, Concept and Context) criteria. We included primary studies with a quantitative study design and reviews examining BCS attendance among women aged 50–69 with data from 2005 onwards in Germany. Harvest plots depicting effect size direction for the different identified sociodemographic inequalities and last two years or less BCS attendance and lifetime BCS attendance were developed.

Results

We screened 476 titles and abstracts and 33 full texts. In total, 27 records were analysed, 14 were national reports, and 13 peer-reviewed articles. Eight sociodemographic variables were identified and summarised in harvest plots: age, education, income, migration status, type of district, employment status, partnership cohabitation and health insurance. Older women with lower incomes and migration backgrounds who live in rural areas and lack private insurance respond more favourably to BCS invitations. However, from a lifetime perspective, these associations only hold for migration background, are reversed for income and urban residency, and are complemented by partner cohabitation. Finally, women living in the former East German states of Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia, as well as in the former West German state of Lower Saxony, showed higher BCS attendance rates in the last two years.

Conclusion

High-quality research is needed to identify women at higher risk of not attending BCS in Germany to address the existing research’s high heterogeneity, particularly since the overall attendance rate still falls below European standards.

Protocol registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer is currently the fifth leading cause of death among women in Germany, with 18,900 deaths in 2022 [1]. Socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer (BC) survival are recognised in Europe [2] and in Germany [3]. In a phenomenon known as the “breast cancer paradox”, women with lower socioeconomic status experience higher mortality rates compared to women with higher socioeconomic status, despite lower incidence in this group [4]. Several explanations have been proposed for this paradox. Higher incidence among women with high socioeconomic status women is related to nulliparity [5], having children at an older age [6], the use of oral combined contraceptives [7], and higher screening attendance [8]. On the other hand, higher mortality and case fatality rates in women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are linked to unhealthier lifestyles (e.g., smoking, diet) [9] and reduced screening attendance [10]. The same pattern was found between Black and Asian minority ethnic women and Caucasian women in the US [11]. Lower screening attendance leads to delayed initiation of treatment and the manifestation of more advanced tumours.

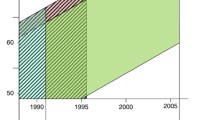

In 2003, the European Commission (EC) requested Member States to implement Organized Screening Programs (OSP), which would systematically invite women aged 50 to 69 years for bi-annual breast cancer screening (BCS), ensuring equitable access for all [12]. Germany started implementing OSP in 2005, reaching full country-wide implementation in 2009. The program is coordinated by the Kooperationsgemeinschaft Mammographie (Mammography Cooperation Group), with 14 regional invitation centres and 94 screening units. Registered targeted women who did not explicitly objected to be invited to screenings are bi-annually invited to take a mammography at no cost at their reference screening unit. Every screening unit, in sparsely populated areas mobile screening unit, covers an area with 800,000 to 1,000,000 inhabitants, and is headed by one or two coordinating doctors. Diagnosed breast cancers are then treated in certified breast centres [13]. Attendance rates have increased since implementation from 49 to 57% among targeted women since but are still well below the 70% EU recommendation [14]. Nevertheless, and possibly overshadowing OSP participation rates, it is important to consider the existence of grey screening in the country. This refers to mammography conducted outside the national program (i.e., via self-invitation) and thus not registered by the screening units, leading to an underestimation of the number of women undergoing screening [15].

Attendance to BCS is not uniform among eligible populations in Germany [16] or worldwide [10]. Several characteristics have been associated with BCS attendance, such as sociodemographic factors, health behaviours, health status, accessibility and logistics, attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs [17,18,19]. Several studies have investigated the presence of BCS sociodemographic inequalities in Germany. Missinne (2015) found a positive correlation between self-reported BCS attendance and income but no association with education [20]. Also, Heinig (2023) found no significant correlation between education and BCS attendance based on data from health insurances (claims data, onward) [15]. Regarding income differences, Lemke (2015) identified high income and lower education as predictive factors for higher BCS attendance based on screening units register-based data [21].

This suggests considerable heterogeneity in the research evidence concerning sociodemographic inequalities, and a review of socioeconomic correlates of BCS attendance in Germany is lacking. As such, a scoping review that encompasses this heterogeneity and summarises research evidence available on sociodemographic inequalities on BCS attendance in the country since the implementation of OSP could facilitate a comprehensive picture and lay the foundation for evidence-based screening interventions to increase screening participation in eligible women. The present scoping review, therefore, aims to identify sociodemographic inequalities in BCS attendance among women aged 50–69 years since the OSP implementation by answering the following questions:

1) What are the existing sociodemographic inequalities in breast cancer screening participation among targeted women following the implementation of an Organized Screening Program in Germany?

2) What are the effect sizes of the sociodemographic inequalities on breast cancer screening attendance among targeted women following the implementation of an Organized Screening Program in Germany?

Methods

We conducted the scoping review in line with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines for scoping reviews [22], and following the five-steps methodological framework proposed by Arksey & O’Malley’s in 2005 [23]. The review protocol, including the search strategy, was registered at the Centre for Open Science (OSF) [24] and is provided as Supplementary File 1.

Eligibility criteria

Following the recommendation for scoping reviews, we employed the PCC (Population, Concept and Context) criteria, where BCS is the concept, Germany is the context and women aged 50–69 years old are the population, as they represent the eligible screening group.

At the screening stage, studies with qualitative designs or non-primary studies, studies reporting data earlier than 2005 (i.e., date for OSP implementation) or not focused on breast cancer screening participation (e.g., focus on the program’s effectiveness), and studies that did not report information on sociodemographic variables (e.g., only general population screening attendance) were excluded. Finally, only studies published in English or German were included.

Information sources and literature search

On January 26, 2024, the following bibliographic databases were searched for the period from January 2005 to January 2024: Web of Science, Scopus, MEDLINE (via PubMed), PsycINFO (via Ovid), and CINAHL (via EBSCO).

The search terms, developed iteratively by the research team, included descriptors of BCS, such as “mammography” or “breast cancer screening”, combined with descriptors of Germany “Germany” and the time frame 2005 onwards. All search strategies are provided as a supplementary file (Supplementary File 2). For those included articles, backward snowballing was performed using the guidelines for snowballing [29]. Furthermore, a manual search of the reference lists of the included systematic or scoping reviews was performed by one researcher (NPB) to identify further relevant articles. To identify grey literature relevant to the scoping review, two team members (NPB and VH) conducted independent searches on the websites of pertinent national public health institutions (e.g., Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Bericht zum Krebsgeschehen in Deutschland, etc.,).

Selection of the sources of evidence

After performing the systematic search of all electronic databases, articles were retrieved, duplicates were removed, and references were imported in Rayyan [25]. Two authors, NPB and VH, independently screened the titles and abstracts and later the full texts of the studies in the next stage. Discrepancies between the researchers were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Data items and data charting process

The data from the eligible studies were extracted in an Excel sheet that was developed, calibrated, tested and refined a priori before three researchers (NPB, VH and HS) charted the data independently. Discrepancies that arose were resolved through discussion. We charted bibliographic information (first author, year of publication, type of publication, study title, setting, aim of the study, funding sources/conflict of interest), methods (type of study, sample size of the analysis, methods of analysis, period coverage, method of reporting data, type of screening), and results (attendance rates, sociodemographic variables, other reported exposure variables, effect sizes, direction of effect sizes, p-values). When articles developed univariate and multivariate models, information from relevant variables was extracted from univariate models for further data synthesis.

Critical Appraisal of the individual sources of evidence

The included studies were critically appraised using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool [26]. Two team members (NPB and VH) assessed the included studies independently, and discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was achieved.

Synthesis of the results

Results were synthesised depending on available information. Effect sizes of sociodemographic variables were extracted from 13 peer-reviewed articles. Given the heterogeneity of study designs, we used harvest plots to summarise the data. These plots are agnostic to the outcomes and measures used and are flexible enough to include any dimension considered relevant (e.g. sample size, study design, etc.) [27]. Sociodemographic information presented in the 14 national reports was synthesised narratively. All analyses were performed with R (version 4.2.3).

Results

From the 476 titles and abstracts screened, 33 articles were included in the full-text screening. Eleven articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the scoping review. Reasons for excluding full-text articles were not reporting breast screening attendance (n = 10), information on sociodemographic variables missing (n = 6), study before 2005 (n = 2), outside Germany (n = 1), and no quantitative or review design (n = 1). Two systematic reviews were identified during the full-text screening, and their reference list was checked for potential articles [4, 28]. Also, backward snowballing from included articles identified 16 further relevant records (14 national reports and 2 articles) bringing the total number of included records to 27 (Fig. 1). Grey literature identified 3,797 relevant records, from which none were finally added to the final review (details in Supplementary File 3).

Study characteristics

The scoping review included 27 records, 13 peer-reviewed articles and 14 national reports. Supplementary File 4 reports the characteristics and summary of findings of the 27 sources. Most of the records (n = 20, [13,14,15,16, 20, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]) utilised nationwide or nationally representative data, while seven records drew upon data from specific regions within Germany (n = 7, [21, 44,45,46,47,48,49]). Publication dates span from 2009 to 2023, with the highest concentration of published articles falling within the 2013–2016 timeframe (n = 10, [13, 20, 31,32,33,34, 41, 43, 45, 46]), closely followed by 2020–2023 (n = 8, [14, 15, 21, 38,39,40, 48, 49]). The reported data covered a broader period, ranging from 2005 to 2021. Specifically, three articles (n = 3, [20, 42, 47]) and two national reports (n = 2, [29, 30]) pertain to the OSP implementation phase spanning 2005–2009. The remaining records (n = 22, [13,14,15,16, 21, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 43,44,45,46, 48, 49]) report data from 2009 onwards, when the OSP was fully implemented. Four included articles (n = 4, [15, 21, 44, 45]) had a cohort study design, nine articles (n = 9 [16, 20, 41,42,43, 46,47,48,49]), and all national reports (n = 14, [13, 14, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]) had a cross-sectional design. The sample sizes of the records ranged from n = 237 [42] to n = 1,151,000 [44] for peer-reviewed articles and n = 4,864,574 [31] to n = 5,887,028 for national reports [14]. Peer-reviewed articles reported three methods for collecting data: self-reported data (n = 7, [16, 20, 21, 42, 43, 47, 49]), claims data (n = 2, [15, 41]), screening units register-based data (n = 3, [45, 46, 48]). One article used claims and register-based data (n = 1, [44]). All national reports reported screening units register-based data (n = 14, [13, 14, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]).

Three articles reported BCS attendance for the last year (n = 3, [41, 42, 44]), five reported attendance in the last two years (n = 5, [16, 43, 45,46,47]) and five reported never having attended to BCS (n = 5, [15, 20, 21, 48, 49]). All national reports reported attendance in the last two years.

Critical appraisal of included sources of evidence

The methodological quality of all included records was rated following the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies given its suitability for the research designs of the included records [26]. All 14 national reports were rated as good, five peer-reviewed articles were rated as good (n = 5, [15, 21, 43, 45, 46]), five as fair (n = 5, [16, 20, 41, 42, 44]) and three as poor (n = 3, [47,48,49]). A study was considered to be good if all the applicable criteria were met, fair if one was not met and poor if two or more were not met. The overall rating of different aspects considered is represented in Fig. 2, and the reasons behind each record’s rating are in Supplementary File 5.

Breast cancer screening attendance rates across studies

Cross-sectional studies reported an average attendance rate of 55.10% (SD = 9.85), cohort studies reported 74.67% (SD = 17.94). The average attendance rate of all records was 57.42% (SD = 12.40). Average lifetime attendance rate was 72.54% (SD = 16.32), attendance in last two years was 53.83% (SD = 8.15), attendance in the last year was 52.3% (SD = 8.34). Two articles did not report overall BCS attendance rates (n = 2, [41, 45]).

Studies with self-reported attendance reported an average attendance rate of 63.84% (SD = 20.27), those based on claims and screening units register-based data showed an average attendance of 54.97% (SD = 6.99).

OSP implementation phase (2005–2009) and the full OSP implementation (2009 onwards) also showed different participation rates: 47.94% (SD = 6.87) and 59.19% (SD = 12.47), respectively. There was an increase in the lifetime attendance rate from 72.54% (SD = 16.32) to 78.48% (SD = 10.22) (n = 4, [15, 21, 48, 49]) when only assessing studies carried since the full OSP implementation.

Evaluation reports of the German mammography screening programme

Fourteen of the included sources are national evaluation reports of the German Mammography Screening Programme, initiated in 2005 and conducted by the Kooperationsgemeinschaft Mammographie [50]. The reports graphically presented participation rates per federal state based on the screening units register-based data, and, as such, have the potential to detect regional inequalities in attendance. No federal state has yet reached the EU recommended rate of > 70% participation of the target population. Still, Lower Saxony, Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia have had the highest participation rates over the last five years [14].

Sociodemographic inequalities in breast cancer screening participation

Sociodemographic inequalities in BCS participation were examined by harvest plots based on vote counting for sociodemographic variables reported in at least two articles: age, education, income, migration status, type of district, employment status, partnership cohabitation and health insurance. Two harvest plots were plotted for the distinct reported outcomes: Attendance during the last one or two years (Fig. 3) and lifetime BCS attendance (Fig. 4). Details on the harvest plots can be found in Supplementary File 6.

Each bar represents a study and illustrates five characteristics of the study: the height of the bars indicates the sample size of the study, the width of the bars reflects the study quality based on the NIH critical appraisal tool, colour denotes the study type (blue: cohort; yellow: cross-sectional), and filling pattern indicates sociodemographic data level source (black: individual; white: regional).

Age (6 effects)

Among those reporting attendance in the last one/two years, 4/5 suggested higher attendance in older women [16, 43, 44, 46], and one suggested no correlation [47]. One study found no significant relationship between age and lifetime BCS attendance [21].

Education (11 effects)

Two studies (three effects) suggested higher attendance in the last one/two years with higher education [42, 44], and three studies suggested the opposite [16, 41, 47]. Two studies revealed a negative correlation [48, 49], and three studies found no relationship [15, 20, 21] for lifetime BCS attendance.

Income (4 effects)

Three studies found a negative correlation between income and attendance in the last one/two years [41, 43, 47], and one study found no correlation [44]. One study found no correlation between lifetime BCS [20], and one study found a positive correlation [21].

Migration status (7 effects)

4/7 studies identified higher lifetime BCS attendance in those with migration status (2 lifetime [21, 49]; 2 last two years [44, 46]). Three studies found no correlation [21, 45, 48]. Here, two effects from the same study illustrated a positive correlation between first-generation migrants and locals, but there was no correlation when estimating second-generation migrants versus locals [21].

Type of district (3 effects)

Two studies found that living in a rural area favours last one/two years BCS attendance (n = 2, [44, 47]), whereas one found no correlation for lifetime BCS attendance (n = 1, [21]).

Employment status (7 effects)

Lemke (2015) contributed 5/7 effects, showing a contextual negative association in two and no relationship in three cases [45]. Two more studies also found no relationship with BCS attendance [21, 47]. Conversely, one study identified a positive correlation between employment status and BCS attendance in the last year [44].

Partnership cohabitation (2 effects)

One study found a positive relationship between cohabitating and lifetime BCS [21], and another found no relationship for BCS in the last two years [47].

Health insurance (2 effects)

One study observed no correlation between health insurance and lifetime BCS [21]. Still, another study identified that compulsory insurance (as opposed to private insurance) was associated with BCS in the last two years [47].

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify sociodemographic inequalities in BCS attendance in Germany following the implementation of the OSP. Eight sociodemographic variables were identified: age, education, income, migration status, type of district, federal state, employment status, partnership cohabitation, and health insurance.

Women are more likely to attend BCS following invitation letters within two years or less as they age, have lower incomes, have a migration background, reside in rural areas, live in certain federal states such as Lower Saxony, Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia, and are insured within the compulsory health insurance system (i.e., do not hold private health insurance; based on one study only). Lifetime BCS attendance is more likely in women with higher incomes, migration backgrounds, urban residency (based on one study only), and cohabitating status with a partner (based on one study only).

Our finding regarding age is similar to a scoping review in Spain [51]. However, the lifetime impact on overall BCS attendance requires further investigation, as in our scoping review, there is a substantial imbalance in research outputs- only one study focused on lifetime attendance [21].

The size and direction of the impact of educational attainment on attending BCS within two years or less remains unclear, as we identified studies reporting opposing results. Considering the quality of the assessed studies, those suggesting higher education as a protective factor yielded higher quality. In this line, Damiani’s (2015) international systematic review found that highly educated women were the most likely to undergo BCS after invitation [52]. Studies examining lifetime BCS attendance found different results, showing that in over half of the studies with high quality, there was no correlation, and in less than half with lower quality, there was a negative correlation between educational attainment and BCS attendance. There were also heterogeneous results concerning the association between income and BCS attendance. Lower income women depicted higher short-term BCS attendance rates and higher income women higher long-term BCS attendance rates.

These findings challenge the breast cancer screening paradox whereby women with higher socioeconomic status are more likely to engage in BCS. In our scoping review, there was no straightforward relationship identified between higher educational attainment or income and higher participation rates. A comparable pattern was identified by a recent international systematic review [10], which indicated that women with higher levels of education or income were no more likely to attend BCS than those with intermediate levels of education or income. It is hypothesised that high SES women utilise alternative screening services, such as grey screening, to a greater extent, and could also have larger concerns about the overall benefits of screenings [53]. Indeed, Berens (2015) exposed that women with higher educational attainment were more likely to make informed choices than those with lower educational attainments in Germany [54].

Moreover, in the context of Germany, a considerable proportion of women with high income may have a private health insurance, often as a result of their employment status as civil servants [55]. For those citizens with private health insurance, the utilisation of any preventive service can be initially borne by the individual and subsequently reimbursed, unless the overall out-of-pocket expenditure in a given year does not exceed a specified threshold (e.g., 500€), potentially jeopardising the use of these services [56]. Indeed, in our review one study suggests that holding private health insurance is associated with lower BCS attendance in the last two years . In line with this finding , private health insurance in Spain also negatively correlates with last two years BCS attendance [57].

Women with migrant backgrounds appear more likely to attend BCS in the short and long term. Over half the studies with fair to good quality support this trend. Contrarily, several studies assessing BCS attendance in other high-income countries [58,59,60] or assessing general cancer screening attendance in Germany [61, 62] found the inverse tendency.

Furthermore, attending BCS within the last two years or less was positively correlated with living in rural areas. Analogously, Serral (2018) found the same association [57]. In the reviewed studies, BCS attendance was higher in Lower Saxony, Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. Except for Lower Saxony, all these states conform are former East German states. Großmann (2023) also noted higher BCS attendance rates in former East German states and suggested that the former centralised healthcare and prevention systems, perceived as state tasks, contributed to women viewing participation as a social responsibility [63].

About two-thirds of the included records found no significant difference between regions with higher and lower unemployment levels, while the remaining third suggested a slightly higher short term BCS attendance in regions with higher unemployment levels. These results are in accordance with Serral (2016), who showed, after adjusting by age, a positive relationship between not working and BCS attendance in Spain [57], while Jensen (2012) found the opposite relationship in Denmark [64].

Partnership cohabitation was positively associated with lifetime BCS but not with last two years or less BCS attendance. The study with a positive relation had a more robust design and better-quality assessment. Similarly, Jolidon (2022) found significantly higher attendance rates among married women compared to unmarried women in Switzerland [65]. Lastly, no study included women with disabilities in their analysis. Andiwijaya’s (2022) systematic review revealed that having a disability was negatively associated with BCS attendance [66].

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge this is the first scoping review to identify sociodemographic inequalities in BCS attendance among women aged 50–69 years since the implementation of the OSP in Germany. In accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines, the search and the screening process was conducted in a transparent and reproducible manner, and the results were visually summarised using harvest plots.

The scoping review identified heterogeneous study designs, which corresponded with the mixed findings: cross-sectional studies indicated nearly 20% lower participation rates than cohort studies. Similarly, there was almost a 20% difference between the average participation rates over the past one or two years and lifetime participation rates (i.e., being lifetime participation higher). Slightly minor differences were found with the data collection method. Here, claims or screening units register-based data reported a 9% higher prevalence than self-reported participation. Finally, BCS participation prevalence during the OSP implementation phase (2005–2009) was 12% lower than after total implementation, and was reported as a compound of formal OSP participation and self-invited participation (i.e., grey screening) [29, 30, 47]. The varied BCS prevalence across study characteristics might align with our scoping review’s mixed findings in sociodemographic inequalities.

Lastly, given the heterogeneity of study designs, it is impossible to distinguish correlation from causation. Accordingly, more cohort studies with objective data sources, such as claims and screening units register-based data, are needed.

Conclusions and implications

This scoping review shows considerable heterogeneity in sociodemographic inequalities in BCS attendance following the implementation of the OSP in Germany. Older women, women with lower incomes, women with migration background, women living in rural areas, women living in former East Germany states and women who are insured in the statutory insurance system respond more favourably to BCS invitations. Regarding lifetime BCS attendance, these associations only hold for migration background, are reversed for income and urban residency, and are complemented by partner cohabitation.

Given that overall attendance is well below European standards, specific sociodemographic groups should be targeted in BCS participation campaigns. At the same time, more high-quality research is needed to identify women at higher risk of not attending BCS in Germany to provide better evidence.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

References

Statistisches Bundesamt. Causes of death 2024 [ https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Health/Causes-Death/_node.html#sprg267092

Lundqvist A, Andersson E, Ahlberg I, Nilbert M, Gerdtham U. Socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer incidence and mortality in Europe—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pub Health. 2016;26(5):804–13.

Eberle A, Luttmann S, Foraita R, Pohlabeln H. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality - A spatial analysis in Bremen, Germany. J Public Health. 2010;18(3):227–35.

Smith D, Thomson K, Bambra C, Todd A. The breast cancer paradox: a systematic review of the association between area-level deprivation and breast cancer screening uptake in Europe. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;60:77–85.

Troisi R, Bjørge T, Gissler M, Grotmol T, Kitahara CM, Myrtveit Sæther SM, et al. The role of pregnancy, perinatal factors and hormones in maternal cancer risk: a review of the evidence. J Intern Med. 2018;283(5):430–45.

Trichopoulos D, Hsieh CC, Macmahon B, Lln TM, Lowe CR, Mirra AP, et al. Age at any birth and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 1983;31(6):701–4.

Cancer CGoHFiB. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347(9017):1713–27.

Gentil-Brevet J, Colonna M, Danzon A, Grosclaude P, Chaplain G, Velten M, et al. The influence of socio-economic and surveillance characteristics on breast cancer survival: a French population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(1):217–24.

Larsen SB, Kroman N, Ibfelt EH, Christensen J, Tjønneland A, Dalton SO. Influence of metabolic indicators, smoking, alcohol and socioeconomic position on mortality after breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):780–8.

Mottram R, Knerr WL, Gallacher D, Fraser H, Al-Khudairy L, Ayorinde A, et al. Factors associated with attendance at screening for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):e046660.

Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh GK, Cardinez C, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78–93.

EC. Screening ages and frequencies 2022 [ https://healthcare-quality.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ecibc/european-breast-cancer-guidelines/screening-ages-and-frequencies

Evaluationsbericht. 2010. Ergebnisse des Mammographie-Screening-Programms in Deutschland. Berlin; 2014.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2021. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2023.

Heinig M, Schäfer W, Langner I, Zeeb H, Haug U. German mammography screening program: adherence, characteristics of (non-)participants and utilization of non-screening mammography—a longitudinal analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1).

Starker AK, Kuhner K. Ronny. Early detection of breast cancer: the utilization of mammography in Germany. J Health Monit. 2017;2(4).

Schueler KM, Chu PW, Smith-Bindman R. Factors Associated with Mammography utilization: a systematic quantitative review of the literature. J Women’s Health. 2008;17(9):1477–98.

Ackerson K, Preston SD. A decision theory perspective on why women do or do not decide to have cancer screening: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(6):1130–40.

Crosby R. Predictors of uptake of screening mammography. Warwick: University of Warwick; 2018.

Missinne S, Bracke P. A cross-national comparative study on the influence of individual life course factors on mammography screening. Health Policy. 2015;119(6):709–19.

Pokora RM, Büttner M, Schulz A, Schuster AK, Merzenich H, Teifke A, et al. Determinants of mammography screening participation–a cross-sectional analysis of the German population-based Gutenberg Health Study (GHS). PLoS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0275525.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Núria Pedrós Barnils V, Härtling H, Singh U, Haug, Schüz B. A scoping review of sociodemographic inequalities on the uptake of breast cancer screening among targeted women in Germany since the implementation of the Organized Screening Program. 2024.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Reviews. 2016;5:1–10.

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute USA. Quality asessment tool for observational and cohort and cross-sectional studies 2021 [ https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Ogilvie D, Fayter D, Petticrew M, Sowden A, Thomas S, Whitehead M, et al. The harvest plot: a method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):8.

Dreier M, Borutta B, Töppich J, Bitzer EM, Walter U. Mammography and cervical cancer screening - A systematic review about womens knowledge, attitudes and participation in Germany. Gesundheitswesen. 2012;74(11):722–35.

Evaluationsbericht 2005–2007. Ergebnisse des Mammographie-Screening-Programms in Deutschland. Berlin; 2009.

Evaluationsbericht 2008–2009. Ergebnisse des Mammographie-Screening-Programms in Deutschland. Berlin; 2012.

Evaluationsbericht. 2011. Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse des Mammographie-Screening-Programms in Deutschland. Berlin; 2014.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2012. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2015.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2013. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2016.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2014. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2016.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2015. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2017.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2016. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2018.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2017. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2019.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2018. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2020.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2019. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2021.

Jahresbericht Evaluation. 2020. Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm. Berlin; 2022.

Vogt V, Siegel M, Sundmacher L. Examining regional variation in the use of cancer screening in Germany. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:74–80.

Willems B, Bracke P. The education gradient in cancer screening participation: a consistent phenomenon across Europe? Int J Public Health. 2018;63(1):93–103.

Starker A, Saß AC. Inanspruchnahme Von Krebsfrüherkennungsuntersuchungen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(5–6):858–67.

Czwikla J, Urbschat I, Kieschke J, Schüssler F, Langner I, Hoffmann F. Assessing and explaining Geographic variations in Mammography Screening participation and breast Cancer incidence. Front Oncol. 2019;9.

Lemke D, Berkemeyer S, Mattauch V, Heidinger O, Pebesma E, Hense H-W. Small-area spatio-temporal analyses of participation rates in the mammography screening program in the city of Dortmund (NW Germany). BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1).

Berens E-M, Stahl L, Yilmaz-Aslan Y, Sauzet O, Spallek J, Razum O. Participation in breast cancer screening among women of Turkish origin in Germany – a register-based study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):24.

Albert US, Kalder M, Schulte H, Klusendick M, Diener J, Schulz-Zehden B, et al. Das Populationsbezogene Mammografie-Screening-Programm in Deutschland: Inanspruchnahme Und Erste Erfahrungen Von Frauen in 10 Bundesländern. Das Gesundheitswesen. 2012;74(02):61–70.

Kuehnle E, Siggelkow W, Luebbe K, Schrader I, Noeding K-H, Noeding S et al. First prospective cross-sectional study on the Impact of Immigration Background and Education in early detection of breast Cancer. Breast Care. 2020:1–7.

Kaucher S, Khil L, Kajüter H, Becher H, Reder M, Kolip P et al. Breast cancer incidence and mammography screening among resettlers in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1).

Kooperationsgemeinschaft Mammographie GbR. Das Mammographie screening Programm Berlin2023 [ https://www.mammo-programm.de/

Martín-López R, Jiménez-García R, Lopez-de-Andres A, Hernández-Barrera V, Jiménez-Trujillo I, Gil-de-Miguel A, et al. Inequalities in uptake of breast cancer screening in Spain: analysis of a cross-sectional national survey. Public Health. 2013;127(9):822–7.

Damiani G, Basso D, Acampora A, Bianchi CB, Silvestrini G, Frisicale EM, et al. The impact of level of education on adherence to breast and cervical cancer screening: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2015;81:281–9.

Aro AR, de Koning HJ, Absetz P, Schreck M. Psychosocial predictors of first attendance for organised mammography screening. J Med Screen. 1999;6(2):82–8.

Berens E-M, Reder M, Razum O, Kolip P, Spallek J. Informed choice in the German mammography screening program by education and migrant status: Survey among First-Time invitees. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142316.

Busse R. The health system in Germany. EUROHEALTH-LONDON-. 2008;14(1):5.

Bremer P. Forgone care and financial burden due to out-of-pocket payments within the German health care system. Health Econ Rev. 2014;4:1–9.

Serral G, Borrell C, Puigpinos IRR. [Socioeconomic inequalities in mammography screening in Spanish women aged 45 to 69]. Gac Sanit. 2018;32(1):61–7.

Ding L, Jidkova S, Greuter MJW, Van Herck K, Goossens M, De Schutter H, et al. The role of Socio-Demographic Factors in the Coverage of breast Cancer screening: insights from a quantile regression analysis. Front Public Health. 2021;9:648278.

Rondet C, Lapostolle A, Soler M, Grillo F, Parizot I, Chauvin P. Are immigrants and nationals born to immigrants at higher risk for delayed or no lifetime breast and cervical Cancer screening? The results from a Population-based survey in Paris Metropolitan Area in 2010. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e87046.

Stuart GW, Chamberlain JA, Milne RL. Socio-economic and ethnocultural influences on geographical disparities in breast cancer screening participation in Victoria, Australia. Front Oncol. 2022;12:980879.

Brzoska P, Abdul-Rida C. Participation in cancer screening among female migrants and non-migrants in Germany: a cross-sectional study on the role of demographic and socioeconomic factors. Med (Baltim). 2016;95(30):e4242.

Starker A, Hövener C, Rommel A. Utilization of preventive care among migrants and non-migrants in Germany: results from the representative cross-sectional study ‘German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1)’. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):86.

Großmann LM, Napierala H, Herrmann WJ. Differences in breast and cervical cancer screening between West and East Germany: a secondary analysis of a German nationwide health survey. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1).

Jensen LF, Pedersen AF, Andersen B, Vedsted P. Identifying specific non-attending groups in breast cancer screening - population-based registry study of participation and socio-demography. BMC Cancer. 2012;12.

Jolidon V, De Prez V, Bracke P, Bell A, Burton-Jeangros C, Cullati S. Revisiting the effects of Organized Mammography Programs on inequalities in breast screening uptake: a multilevel analysis of Nationwide Data from 1997 to 2017. Front Public Health. 2022;10.

Andiwijaya FR, Davey C, Bessame K, Ndong A, Kuper H. Disability and participation in breast and cervical Cancer screening: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ulrike Haug for her insightful comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing - original draft. VH: Data curation, Formal Analysis. HS: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis. BS: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Writing - review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (scoping review).

Consent for publication

Not applicable (scoping review).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pedrós Barnils, N., Härtling, V., Singh, H. et al. Sociodemographic inequalities in breast cancer screening attendance in Germany following the implementation of an Organized Screening Program: Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 24, 2211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19673-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19673-6