Abstract

People living with mental illness experience poorer oral health outcomes compared to the general population, yet little is known about their oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The aim of this mixed-methods systematic review was to synthesise evidence regarding oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of people living with mental illness to inform preventative strategies and interventions. Database searches were conducted in PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest, and Scopus with no limitations placed on the year of study. All studies available in the English language, that explored the oral health knowledge, attitudes, and/or practices of people with a mental illness were included. Articles were excluded if they primarily pertained to intellectual disability, behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, drug and alcohol or substance use, or eating disorders. A thematic synthesis was undertaken of 36 studies (26 high-moderate quality), resulting in 3 themes and 9 sub-themes. Study participants ranged from n = 7 to n = 1095 and aged between 15–83 years with most having a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or bipolar affective disorder. People diagnosed with a mental illness were found to have limited oral health knowledge, particularly regarding the effects of psychotropic medication. Various barriers to oral health care were identified, including high dental costs, the negative impact of mental illness, dental fears, lack of priority, and poor communication with dental and health care providers. Study participants often displayed a reduced frequency of tooth brushing and dental visits. The findings highlight the potential for mental health care providers, oral health and dental professionals, mental health consumers, and carers to work together more closely to improve oral health outcomes for people with mental illness. The systematic review protocol is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), (registration ID CRD42022352122).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental illness encompasses a broad range of conditions that affects a person’s way of thinking or behaviour causing distress or impairment [1]. Globally, the impact of mental illness is significant and is ranked in the top 20 causes of disease burden [2]. It is estimated that approximately 1 in 8 people worldwide currently live with a diagnosable mental illness [1].

The impacts of mental illness are multifaceted, with people experiencing social, economic, and physical health adversities [3, 4]. Poor overall health, reduced life expectancy [5, 6], and increased risk of metabolic-related illnesses secondary to psychotropic medication use and illness symptomology [7] are often reported. Amotivation and anhedonia (loss of ability to feel pleasure) results in reduced engagement in self-care activities, including self-hygiene and exercise [8]. This may contribute to a sedentary lifestyle, poor diet with reduced fruit and vegetable intake [9, 10] and increased intake of sugary drinks [11]. Obesity secondary to antipsychotic medication use [12] can occur, and higher rates of smoking are reported [13].

People living with mental illness experience significantly poorer oral health outcomes compared to the general population [14,15,16,17,18,19]. They are at higher risk of tooth loss and oral health diseases including periodontal disease and dental caries [18, 20]. Psychotropic medications, used in treatment are associated with hyposalivation, causing dry mouth and resultant dental caries [20, 21]. However, authors Persson, Olin and Ostman [22] state that this population may have a poor understanding of the impact of mental illness on oral health which is secondary to feelings of shame regarding their oral health status. They may have had previous traumatic experiences that influenced decisions about seeking dental care [22]. Reduced self-care such as brushing teeth can impact a person’s oral health status [23]. For many people who experience mental illness, the financial cost of accessing regular dental care may be prohibitively expensive [24]. The focus of most systematic reviews has been on highlighting the oral health adversities for this population. To date, no review has focused on the oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of people living with mental illness. This review addresses this gap by answering the question what are the oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of people living with mental illness?

Aims

The aim of this systematic review was to synthesise the available evidence regarding oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of people living with a mental illness to help inform future preventative strategies and interventions.

Definition of terms

The term ‘people living with a mental illness’ has been used throughout this review to include any person who has received a clinical diagnosis of a mental illness or mental disorder.

Knowledge includes understanding the relationship between oral health and mental illness, complications and impact of prescribed medication, knowledge on seeking out oral health resources and causes of poor oral health.

Attitudes refers to a person’s perception towards oral health, including perceived barriers to attending to oral health and attending dental visits.

Practices included the actions that a person engages in to maintain oral health, including tooth brushing frequency, type of tooth brushing aid used to brush teeth and dental visits. For the purpose of this review, practices did not include dietary practices.

Methods

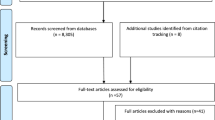

This mixed-methods review was guided by the work of Khan et al [25] and included developing the review question, identifying relevant studies, quality assessment, and summarising and interpreting the evidence. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and reporting checklist guided reporting [26]. The systematic review protocol is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), (registration ID CRD42022352122).

Eligibility criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included: published in the English language, participants had a diagnosis of mental illness, and the study explored at least one study outcome (knowledge, attitude, or practice toward oral health). All studies including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies were eligible for inclusion to ensure the breadth of evidence was captured. Any experimental studies with a pre-survey component were also included. No restrictions were placed on the year of publication, quality, or study setting to ensure all available literature was included. Studies of people with primary alcohol or substance use disorders, intellectual disability, and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia were excluded due to the additional oral health complexities associated with these co-morbidities. Studies that focused on people who experience eating disorders were also excluded due to the additional oral health complications that arise secondary to an eating disorder.

Data sources, search strategy, and study selection

A systematic search of all peer-reviewed literature published up until August 2022 was undertaken in consultation with a university librarian. Six databases were searched (PubMed, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest, and Scopus) using various search strategies (see supplementary file for an example). Keywords used in the search included: Mental illness*, mental disorder, psychiatry*, oral health, oral health care, oral hygiene, dental care, knowledge, attitude*, practice*, perception, and awareness. Database-specific index terms were used in the search and reference lists of included studies were hand-searched. Combination search terms including ‘Boolean’ operators were used. Within each database search, an English language filter was also applied. A repeat database search was conducted in October 2023 to ensure all studies were captured.

The results from database searches were imported from Endnote bibliographic software into the Cochrane systematic review management program, Covidence, where duplicate references were removed. Covidence, was used to manage the screening process. Titles and abstracts of studies were assessed by two separate investigators (AJ: all studies and AG: 67%, AK: 17%, TR: 1%, LR: 15%) using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full text was screened by two separate investigators (AJ and AG). Any discrepancies between reviewers were resolved with team discussion. The selection process and the final studies included in the systematic review are illustrated in Fig. 1 using the current PRISMA flowchart [26].

Data extraction and data synthesis

Data extraction tables were developed by the team to extract relevant information from the included studies. The information included author, year of publication, country, article type, study characteristics (design, participant demographics), study findings, and quality assessment rating.

A thematic synthesis approach was used to collate, analyse, and present the findings of the study [27]. The full texts of all included studies were closely read and re-read, and codes were generated using a hybrid inductive and deductive approach. Codes were grouped into meaningful themes and subthemes that reflected the overall study aim. The generated themes were reviewed by a second investigator (AG) and revised accordingly. A team meeting was held to explore interpretations and finalise themes. Direct quotes are used to support the themes generated. As statistic pooling was not possible due to a lack of homogeneity within the included studies, quantitative data are presented in narrative format to support the themes and sub-themes. Three major themes and nine subthemes were identified from the studies- see Table 1.

Quality assessment

The quality of studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist that aligned with the methodology of corresponding studies [62] and included the checklist for qualitative research [63], analytical cross sectional studies [64], cohort studies [65], randomized controlled trials [66], and case control studies [67]. Two separate investigators (AJ: all studies and LR: 50%/TR: 50%) scored the included studies by assigning 1 point for each applicable item. A third author (AG) was consulted to resolve any discrepancies. After ascertaining consensus among authors, cut off values were established including, 0–59% considered poor quality, 60–79% considered moderate quality, and 80% or greater considered high quality [68]. No articles were excluded in this systematic review based on quality appraisal.

Results

Insert PRISMA

There were 36 studies included in this review, published between 1995 and 2022 and conducted in 15 countries including, United Kingdom (6/36), USA, (5/36), India (4/35), Denmark (4/36), Australia (2/36), Netherlands (2/36), Taiwan (2/36), Japan (2/36), Turkey (2/36), Sweden (2/36), France (1/36), Norway (1/36), Ethiopia (1/36), Brazil (1/36), and Singapore (1/36). The sample size ranged from n = 7 [39] to 21,417 [60] . The age of participants ranged from 15 to 83 years and consisted of mostly male participants.

Most authors (32/36) reported on a diagnosis of the study population with 23 of the 32 studies having a combination of disorders within their sample. The remaining studies had populations with schizophrenia (n = 6), first episode psychosis (n = 2), and psychotic illness in general (n = 1). Four studies did not include a diagnosis of the participants (See Table 2). Of the 36 studies included in this review, the majority were conducted in a community setting, with 10 conducted in an in-patient (hospital) setting. Of the 36 studies, 27 were quantitative and eight were qualitative, and one was mixed methods, with two of the 36 included studies using a validated tool. The quality of studies was assessed with 21 studies considered high, five considered moderate, and 10 considered poor (See Tables 3 and 4). Studies rated as having poor quality were lacking across certain assessment criteria, the most common being lack of identification of confounding variables and lack of measurement of exposure/outcomes in a valid and reliable way (see Table 4). In seven of the 10 studies some of the assessment criteria were also ‘unclear’ which resulted in a lower quality score. There were no significant discrepancies though between quality of studies and their findings. The themes that emerged from the poor quality studies followed the same trends as the moderate and high quality studies.

The three themes arising from the review were categorised under oral health knowledge, oral health attitudes, and oral health practices.

Theme 1: Oral health knowledge “My medication didn’t interfere with anything “

Authors of seven studies [24, 28,29,30,31,32,33] examined oral health knowledge with one [24] of these studies being qualitative and two [28, 29] using a tool a 15-item Oral Health Knowledge questionnaire [28] and 35-item questionnaire adapted and developed from Taiwan Health Promotion School [29]. Oral health knowledge was found to be related to knowledge regarding preventative oral health practices and the side effects of psychotropic medication.

Preventative oral health care

Most studies reported low or basic levels of oral health knowledge irrespective of diagnosis, gender, or age [28,29,30, 32]. The two studies where validated tools were used, found that participants scored less than 45–50% in the oral health knowledge questions [28, 29]. Participants had limited understanding regarding preventative dental visits, and the importance of regular tooth brushing and flossing, reporting that they learned of this after experiencing significant decay or tooth loss [24]. In the only study exploring preventative dental visits, 82.5% of participants were unable to identify that regular dental check-ups were necessary for maintaining good oral health [31]. In another study, two-thirds of the participants could not identify a dentist to visit [33].

Side effects of psychotropic medication

Authors of two studies explored the knowledge of mental illness, psychotropic medications, and association with oral health [24, 30]. The results of one study indicated that 86% of participants did not know that medication they received may contribute to the development of cavities [30]. Similarly, McKibbin, Kitchen-Andren [24] found that nearly all participants had limited knowledge regarding medication side effects and oral health impact:

Theme 2: Oral health attitudes- “it isn’t just a matter of brushing teeth”

The attitudes of individuals with a mental illness towards oral health were reported in 13 studies, including six quantitative [29, 34,35,36,37,38] and seven qualitative [22, 39,40,41,42,43,44], One study [29] used a validated tool (35-item questionnaire adapted and developed from Taiwan Health Promotion School). The oral health attitudes were summarised as, impact of mental illness and oral health not a priority.

Impact of mental illness

In a study conducted by Ho et al. [42] people living with mental illness identified coping with their mental health condition and dealing with life stressors as a challenge in attending to preventative oral health behaviours. This was exemplified in quotes such as the following:

‘I don’t clean my teeth often enough. I used to clean my teeth twice a day before… I got diagnosed. You know when you get depressed you just stop showering, you stop cleaning your teeth, you stop shaving’ [42].

Authors of three studies [39, 40, 43] identified symptomology of mental illness as a barrier to attending dental visits, with symptoms of mental illness preventing participants from making an appointment, catching transport and getting to their appointment on time [40]:

‘On days when you feel hopeless and think of ending your life, you forget to brush your teeth and to go to the dental clinic’ [40].

‘Yes, and people think it’s so easy … ‘just’ a matter of brushing your teeth. But it isn’t ‘just’ a matter of brushing teeth. Some mornings, it’s like I can hardly manage to drag myself out of bed and on mornings like that I just don’t have the spare energy to go out and grab a toothbrush’ [43].

‘I mean I can spend days when I can’t actually get out of bed never mind think about cleaning my teeth, you know that’s just not something that’s going to happen’ [39]

The impact of mental illness symptoms was demonstrated to not only impact attendance at dental appointments but have a further impact on mental health:

‘My mental illness causes me to have bad periods when I need hospitalization. Then I forget appointments at the dental clinic and risk falling out and losing my treatment. The dentist thinks that I do not care or that I am a difficult person, and I feel ashamed’ [40]

Oral health not a priority

Prioritisation of oral health was explored by authors in 10 studies [22, 34,35,36,37,38,39, 41, 43, 44]. Participants described oral hygiene as a challenge, one that was not assigned a priority in comparison to other self-care priorities [43]. Complementary to this, in one study authors reported that 84.7% of participants perceived oral health as having little influence in their lives [35]. In another study it was found that participants did not view oral health as a priority when experiencing symptoms of mental illness [41]:

In another study by Mishu et al., [39], participants perceived that oral health was not considered important from the perspectives of mental health care providers and other health professionals:

‘I’ve heard them say it before you know ‘we’re not experts in physical health’, but you know what you, you are my consultant psychiatrist, you are my mental health nurse, you are my social worker, you are whoever, you don’t have to be an expert in the field to put in my CPA [Care Plan Approach] letter or my discharge letter or the letter to my GP [General Practitioner]-when was the last time I saw a dentist or when’s the last time I had a physical health check . . . you know, to advocate for me and that’s what we need, we need people to support us, we need people to advocate for us’[39].

These same participants wanted to be involved in the planning and decision making of their oral health care [39].

Theme 3: Oral health practices- “I did not go to the dentist for over 3 or 4 years…”

In 33 studies [24, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] the oral health practices of people with a mental illness were assessed. Of the 33 studies, 25 studies were quantitative [28,29,30,31,32,33,34, 34,35,36,37,38,39, 45, 46, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], seven were qualitative [24, 25, 39,40,41,42, 44], and one study was mixed methods [47]. One study [29] used a validated tool (35-item questionnaire adapted and developed from Taiwan Health Promotion School). Oral health practices included toothbrushing aids, frequency of brushing, frequency of dental visits and barriers to accessing dental care including, cost, practical barriers, poor communication with dentists and health care providers, and dental fears.

Tooth brushing aids

In eight studies [32,33,34,35, 38, 49, 58, 61] the type of aid used to brush teeth, including toothbrush/toothpaste were described. A wide range of toothbrush ownership rates ranging from 38.3% [34] to 98% [58] were reported. One study with the lowest rates of toothbrush aid (38.3%) did have a smaller and younger population compared to other studies [58]. Studies that reported higher rates of toothbrush ownership had formal support services in place, including being admitted to a rehabilitation unit, having an onsite-dental clinic at an inpatient facility, or a care coordinator in the community [32,33,34]. In one study that reported lower rates of toothbrush use [38], it was found that participants did use other means to brush their teeth including finger and powder (12.8%) and tree stick (4.4%) which could be attributed to cultural preference.

Frequency of brushing

In studies that assessed frequency of brushing, rates of brushing teeth twice a day ranged from 2.7% [35] to 72.1% [33]. In three studies it was reported that 10% or less of participants brushed twice a day [35, 38, 49]. Daily brushing ranged from 31.1% [57] to 72.1% [38] with the majority of authors reporting daily brushing below 40% [33, 34, 48, 52, 57]. Although authors of one study reported high rates of toothbrush ownership (98%), frequency of brushing was low with 40% of participants brushing between once a day to a few times a-week [34]. In the one study that used a tool to assess oral health practices [29], participants scored 41% or less (4.1 and 3.6/10) on questions related to correct toothbrushing practices [29].

Dental visits

In 14 studies [30,31,32,33, 36, 38, 46, 48, 51, 57,58,59,60,61] participants’ practices regarding dental visits were assessed. The majority of participants that reported attending the dentist either in the past year or either annually or greater ranged from 15.1% [48] to 29% [32]. One study involving participants who had formal mental health support reported much higher rates (69%) of yearly dental visits [46]. In five studies, between 23.6% [48] to 80.5% [57] of participants would see a dentist as a result of having a dental concern or symptom [61].

Barriers to accessing dental care

Authors of nine studies [24, 38, 39, 41, 42, 44,45,46,47] identified cost as a barrier to visiting the dentist. In studies that explored cost, it was suggested that 14.6% [38] to 39% [45] of participants cited cost as a barrier to visiting the dentist with limited income, lack of insurance [44], and current financial situation [24, 41, 47] as contributing factors:

‘I did not go to the dentist for over 3 or 4 years. Because of my debts. I am in debt restructuring; I cannot really pay the dentist’ [41].

‘The money you have to pay, it’s unbelievable’ [47].

‘I had to come up with $1000 down plus $400 a month before he (the dentist) would even schedule me…So that took a while…cause I only [receive] $577 on disability’ [24].

In one study, a participant described that they were not able to afford necessities associated with living as well as dental care [39]:

‘Because it’s having access to quality dental care and if it’s costing you 45 quid to go

now and a bit of a squirt and clean 45 quid is, you know well that’s Monday, Tuesday,

Wednesday, Thursday’s benefits for me well what shall we not pay? Shall we not pay my

rent, shall we not pay my council tax; so I am not going see my kids, yeah; no, I am okay

with brown teeth and a bit of plaque. You know you’re asking people to make those sort of

choices’ [39].

Participants in the study by McKibbin [24], reported that dental treatment expense dictated the treatment received with participants opting for the most cost-effective option:

‘It’s a struggle to find somewhere to help you…do fillings and stuff cause it’s a couple hundred bucks you know and that’s a lot. If you have a filling…I don’t even know, like they usually don’t…like…my Medicaid, all they do is pull them, they don’t, they won’t fill them… So it’s just, you have one cavity, you have to get the whole tooth pulled if you want to be out of pain’ [24]

Poor communication with dentists and health care providers

Authors of three studies [39, 42, 44] identified poor communication as a barrier that impeded participants’ oral health. Wright et al. [44] identified a lack of perceived empathy by dentists, and lack of communication by dentists as barriers. Similarly in a study conducted by Mishu et al., [39], participants reported that they felt dental professionals lacked understanding regarding mental illness.

‘This level of education is really needed with these groups of individuals around trauma, and you know, so that they are psychologically informed and trauma informed. You know who wants to put anybody through any kind of distress, but you know so it’s a group of people that really do need to learn more about their patients.’ [39]

Additionally, Wright et al. [44] found that communication barriers were not isolated to dentists, with participants identifying a lack of communication on oral health by psychiatrists as a barrier.

Ho et al.,[42] identified that even though consumers may have a high level of health literacy, miscommunication still occurred. Some participants identified that the language used by dental professionals made it difficult to understand their oral health:

‘So I think with a lot of dentists, they know what they are talking about… but we don’t. We don’t understand what they’re talking about. So it’s a bit hard to understand what they’re talking about…. I mean the way they explain it. We don’t understand all these things. You know some of the terminology. If they showed a chart or something like that or they explained it a bit more in layman’s terms… it would be a lot easier… Well it’s your teeth. You want to know what is going on with your own mouth ‘cause you can’t see. So you want to be able to know what they’re seeing especially when they are poking and probing in you’ [42].

Dental fears and other practical barriers

Participants in seven studies [38, 39, 42, 44,45,46, 57] identified fear or anxiety regarding dental visits. This ranged from 2.1% [31] to 27% [38] of participants. Additionally, practical barriers such as difficulties accessing dental providers due to distance and transportation [39, 44, 45] and time constraints [38] were also identified by participants. These practical barriers were not limited to those in the community setting, with people in inpatient settings identifying a lack of access to brushing teeth in the evening for individuals in wheelchairs, and long queues due to limited sink numbers [37].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to synthesis the available evidence regarding oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of people with a mental illness. The findings from this review indicate that individuals living with a mental illness have limited oral health knowledge around good oral health practices and the impact of psychotropic medications. Oral health is not a high priority and there are lower levels of frequency of toothbrushing and preventative dental visits among this population. The identified themes in this review particularly the limited knowledge and lack of priority in oral health seems to be a common feature observed in vulnerable and at-risk population groups like those with systemic diseases [69, 70].

Tooth brushing practices appeared to be generally low irrespective of study location, diagnosis, age, or gender. Despite current recommendations of brushing twice daily to prevent oral health disease most participants only brushed once a day, and even these rates were found to be consistently low ranging from 31.1% [57] to 72.1% [38]. Brushing twice a day is highly recommended to reduce the risk of severe periodontal disease [71] and dental caries [72] as it helps prevent the build-up of bacteria [72]. The low rates of tooth brushing frequency may be influenced by the lack of oral health knowledge evident among this population. Other contributing factors identified in this study include lower priority for oral health as well as the sense of apathy experienced by individuals living with a mental illness.

Authors of studies with an emphasis on oral health knowledge found that participants were only made aware of the importance of preventative practices when they developed a problem that required contact with a dental professional [24], suggesting that increased education and knowledge may improve preventative practices such as toothbrushing. In an interventional study, improvements were found in the frequency of brushing after participants in chronic psychiatric units were provided with education-based interventions [29].

Regular dental visits were also consistently low among this population group, with one study identifying lower dental visits and lower brushing frequency compared to the general population [58]. In studies that took place in in-patient settings [30, 32] or had ongoing psychiatric clinic visits [22], dental visits were noted to appear slightly higher than for study populations in the community settings. This suggests that mental health care providers and carers could play a role in supporting the oral health of people with a mental illness, especially as they are more likely to have more frequent contact than dental practitioners. Both mental health care providers and carers could assist in making and attending dental appointments, providing prompts to attend to activities of daily living such as attending to regular toothbrushing and providing psychoeducation regarding the oral health implications of psychotropic medications and preventative oral health practices to reduce the needs of future dental treatment.

However, before any supportive strategies can be developed it is important to consider the barriers to oral health care identified. Limited access to dental services was a key barrier and could be attributed to the perceived unaffordability of dental services resulting in a reduced number of dental visits by those with a mental illness [24, 38, 41, 45]. Financial barriers to accessing dental visits are not isolated to individuals with a mental illness with countries such as Australia reporting that approximately 39% of people over the age of 15 years avoid or delay visiting a dentist due to cost [73]. It is important to note that people living with a mental illness are likely to experience higher rates of unemployment and socioeconomic disadvantage [4] therefore impacting on affordability of dental services. Increasing accessibility to dental services and increasing awareness of services available to vulnerable populations could achieve higher rates of dental visits within this population, especially for preventative services, and reduce the long-term need requirement of invasive dental treatment.

Communication was identified as a barrier by individuals with a mental illness which was not isolated to dental practitioners, however extended to communication of oral health implications by psychiatrists. This barrier may contribute to the perceived lack of oral health knowledge among people living with a mental illness experience. It was found in this review that the language used by dentists in communicating dental care needs was also perceived as a barrier. Communication as a barrier with dental practitioners is not isolated to individuals living with mental illness, and has been found to extend into other at-risk population groups [73]. In the space of eating disorders, dieticians have reported a lack of dental professionals trained in trauma informed care which can have a negative impact on the clients’ needs [74]. Another recent study involving foster carers of children in out of home care found that the poor chairside manner of dental professionals impacted negatively on the behaviour of children especially those who were traumatised by past experiences [75]. Having increased awareness of the communication needs of people living with a mental illness, including the language used by health care providers when explaining oral health care needs, should be considered, to ensure that individuals with a mental illness can have better comprehension of shared information.

Dental anxiety and dental fear were reported in almost a quarter of studies. For these people, additional support or assistance from carers may assist in reducing anxiety or fear associated with dental visits. Additionally, considering these findings health care providers could advise carers that transportation can pose an additional barrier to attending dental visits and therefore assistance with this could increase the uptake of care as well as reduce anxiety. Although there are limited studies that have explored the carers’ role in promoting oral health within this population, it does appear that external support could play a role in oral health promotion [76].

Lastly, individuals with mental illness particularly in inpatient settings may face practical barriers in maintaining oral health like wheelchair access and availability of adequate sinks for toothbrushing. Similar issues have been cited for other vulnerable groups like those with disability [73] with many recommending making adjustments to buildings for equitable access to oral health care and regularly auditing access to such facilities [74, 77]. Similar strategies could be adopted for individuals with a mental illness when developing mental health care plans, designing models of care, and in the refurbishment of mental health units.

Limitations

The majority of the studies reviewed included multiple conditions of mental illness and thus it was difficult to differentiate the findings based on the severity of the illness. Future studies examining single conditions or diagnoses would address this gap and add to the knowledge base. We were unable to differentiate the findings between low- and high-income countries. Furthermore, all studies included in this review that examined oral health knowledge were from higher income countries. Culture and infrastructure in countries may influence the oral health of people with mental illness and therefore this requires further exploration. Lastly, this study did not include unpublished studies, or studies that were in languages other than English, therefore there is a possibility that not all evidence in this field were retrieved.

Conclusion

This review has highlighted to health care providers, policymakers, and researchers, some of the challenges faced by people living with a mental illness that affect their oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices as well as their carers. The findings of this review suggests that although people with a mental illness experience barriers and challenges associated with cost, symptomology of illness, and general lack of oral health knowledge, health care providers and carers, could be involved in facilitating oral health promotion, including working in partnership with people with a mental illness to improve their oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Upskilling of dental professionals in trauma informed care may promote the communication between dentists and people living with a mental illness. Additionally, providing training for mental health care providers to promote preventative dental practices may further reduce oral health disparities providing an opportunity for education and oral health care reminders for people living with mental illness. Further comprehensive and well-designed studies examining the experience of people living with a mental illness, their carers, and mental health care providers are required to improve current evidence in this area.

Relevance for clinical practice

Health professionals providing care to individuals with a mental illness should be aware of their lack of adequate knowledge, attitude, and practices towards oral health. Health care professionals could utilise opportunities of contact with people with a mental illness to provide oral health education particularly around preventative oral health practices, such as tooth brushing and the oral health implications of psychotropic medications. Additionally, mental health providers can promote the importance of regular dental visits and aid in making and attending dental appointments along with regular audits to identify practical barriers to oral health care. Mental health care providers and dental providers also need to ensure communication with people living with mental illness regarding oral health is tailored to the needs and oral health literacy levels of people with a mental illness. Carers, both paid and unpaid, may also be able to play a role in promoting oral health within this population as demonstrated in other vulnerable population groups [74]. Mental health care providers may utilise contact with carers to provide education regarding the importance of oral health care, including tooth brushing and dental visits, for the person they are caring for. Lastly, it is important to point out that these implications for clinical practice are broad and not specific to mental illness severity and settings due to the study limitations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Mental disorders. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders.

Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–50.

Burns JK. Poverty, inequality and a political economy of mental health. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2015;24(2):107–13.

Fryers T, Melzer D, Jenkins R. Social inequalities and the common mental disorders: A systematic review of the evidence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(5):229–37.

Lambert TJ, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Medical comorbidity in schizophrenia. Med J Aust. 2003;178(S9):S67-70.

Grigoletti L, Perini G, Rossi A, Biggeri A, Barbui C, Tansella M, et al. Mortality and cause of death among psychiatric patients: a 20-year case-register study in an area with a community-based system of care. Psychol Med. 2009;39(11):1875–84.

Samaras K. Cardiometabolic Risk and Monitoring in Psychiatric Disorders. Cardiovascular Diseases and Depression: Springer; 2016. p. 305–31.

Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Stubbs B, Ward PB, Rosenbaum S, Soundy A, et al. Negative symptoms are associated with lower autonomous motivation towards physical activity in people with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:128–32.

Mitchell A, Hill B. Physical health assessment for people with a severe mental illness. British Journal of Nursing. 2020;29(10):553–6.

Shiers D, Jones PB, Field S, Shiers D, Jones PB, Field S. Early intervention in psychosis: keeping the body in mind. British J Gen Prac. 2009;59:395–6.

Teasdale SB, Ward PB, Samaras K, Firth J, Stubbs B, Tripodi E, et al. Dietary intake of people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;214(5):251–9.

Working Group for Improving the Physical Health of People with SMI. Improving the physical health of adults with severe mental illness: essential actions (OP100). London; 2016. Report No.: OP100.

Dickerson F, Schroeder J, Katsafanas E, Khushalani S, Origoni AE, Savage C, et al. Cigarette Smoking by Patients With Serious Mental Illness, 1999–2016: An Increasing Disparity. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):147–53.

Kisely S, Baghaie H, Lalloo R, Siskind D, Johnson NW. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and severe mental illness. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(1):83–92.

Kisely S, Sawyer E, Siskind D, Lalloo R. The oral health of people with anxiety and depressive disorders - a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:119–32.

Yang M, Chen P, He M-X, Lu M, Wang H-M, Soares JC, et al. Poor oral health in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:3–9.

Matevosyan NR. Oral Health of Adults with Serious Mental Illnesses: A Review. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(6):553–62.

Kisely S, Lake-Hui Q, Pais J, Lalloo R, Johnson NW, Lawrence D. Advanced dental disease in people with severe mental illness:systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):187–93.

Kenny A, Dickson-Swift V, Gussy M, Kidd S, Cox D, Masood M, et al. Oral health interventions for people living with mental disorders: protocol for a realist systematic review. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2020;14:24.

Cockburn N, Pradhan A, Taing MW, Kisely S, Ford PJ. Oral health impacts of medications used to treat mental illness. J Affect Disord. 2017;223:184–93.

Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis. 2003;9(4):165–76.

Persson K, Olin E, Östman M. Oral health problems and support as experienced by people with severe mental illness living in community-based subsidised housing - a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18(5):529–36.

Ciftci B, Yıldırım N, Sahin Altun O, Avsar G. What Level of Self-Care Agency in Mental Illness? The Factors Affecting Self-Care Agency and Self-Care Agency in Patients with Mental Illness. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(6):372–6.

McKibbin C, Kitchen-Andren K, Lee A, Wykes T, Bourassa K. Oral Health in Adults with Serious Mental Illness: Needs for and Perspectives on Care. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51(2):222–8.

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(3):118–21.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Almomani F, Williams K, Catley D, Brown C. Effects of an oral health promotion program in people with mental illness. J Dent Res. 2009;88(7):648–52.

Kuo M-W, Yeh S-H, Chang H-M, Teng P-R. Effectiveness of oral health promotion program for persons with severe mental illness: a cluster randomized controlled study. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Hede B, Petersen PE. Self-assessment of dental health among Danish noninstitutionalized psychiatric patients. Spec Care Dentist. 1992;12(1):33–6.

Teng P-R, Su J-M, Chang W-H, Lai T-J. Oral health of psychiatric inpatients: a survey of central Taiwan hospitals. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(3):253–9.

Khokhar WA, Williams KC, Odeyemi O, Clarke T, Tarrant CJ, Clifton A. Open wide: a dental health and toothbrush exchange project at an inpatient recovery and rehabilitation unit. Ment Health Rev J. 2011;16(1):36–41.

Stevens T, Spoors J, Hale R, Bembridge H. Perceived oral health needs in psychiatric in-patients: Impact of a dedicated dental clinic. Psychiatrist. 2010;34(12):518–21.

Adams CE, Wells NC, Clifton A, Jones H, Simpson J, Tosh G, et al. Monitoring oral health of people in Early Intervention for Psychosis (EIP) teams: The extended Three Shires randomised trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;77:106–14.

Agarwal D, Kumar A, CM B, Kumar V, Sethi S. Oral health perception and plight of patients of schizophrenia. Int J Dental Hygiene. 2021;19(1):121–6.

Hede B. Dental health behavior and self-reported dental health problems among hospitalized psychiatric patients in Denmark. Acta Odontol Scand. 1995;53(1):35–40.

Ngo DYJ, Thomson WM, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Ang K-Y. The oral health of long-term psychiatric inpatients in Singapore. Psychiatry Res. 2018;266:206–11.

Sogi G, Khan S, Bathla M, Sudan J. Oral health status, self-perceived dental needs, and barriers to utilization of dental services among people with psychiatric disorders reporting to a tertiary care center in Haryana. Dental Research Journal. 2020;17(5):360–5.

Mishu MP, Mehreen Riaz F, Macnamara A, Sabbah W, Peckham E, Newbronner L, et al. A Qualitative Study Exploring the Barriers and Facilitators for Maintaining Oral Health and Using Dental Service in People with Severe Mental Illness: Perspectives from Service Users and Service Providers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):4344.

Bjørkvik J, Henriquez Quintero DP, Vika ME, Nielsen GH, Virtanen JI. Barriers and facilitators for dental care among patients with severe or long-term mental illness. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;36(1):27–35.

Kuipers S, Boonstra N, Castelein S, Malda A, Kronenberg L. Oral health experiences and needs among young adults after a first-episode psychosis : a phenomenological study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2018;25(8):475–85.

Ho HD, Satur J, Meldrum R. Perceptions of oral health by those living with mental illnesses in the Victorian Community - The consumer’s perspective. Int J Dental Hygiene. 2018;16(2):e10–6.

Villadsen DB, Sørensen MT. Oral Hygiene – A Challenge in Everyday Life for People with Schizophrenia. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2017;38(8):643–9.

Wright WG, Averett PE, Benjamin J, Nowlin JP, Lee JGL, Anand V. Barriers to and Facilitators of Oral Health Among Persons Living With Mental Illness: A Qualitative Study. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72(2):156–62.

Hall JP, LaPierre TA, Kurth NK. Oral Health Needs and Experiences of Medicaid Enrollees With Serious Mental Illness. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(4):470–9.

Persson K, Axtelius B, SÖderfeldt B, Östman M. Monitoring oral health and dental attendance in an outpatient psychiatric population. J Psychiatr Mental Health Nurs. 2009;16(3):263–71.

Waplington J, Morris J, Bradnock G. The dental needs, demands and attitudes of a group of homeless people with mental health problems. Community Dent Health. 2000;17(3):134–7.

Alkan A, Cakmak O, Yilmaz S, Cebi T, Gurgan C. Relationship Between Psychological Factors and Oral Health Status and Behaviours. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13(4):331–9.

Anita M, Vidhya Rekha U, Kandavel S. Oral hygiene status, dental caries experience and treatment needs among psychiatric outpatients in Chennai, India. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development. 2019;10(12):1172–7.

Bertaud-Gounot V, Kovess-Masfety V, Perrus C, Trohel G, Richard F. Oral health status and treatment needs among psychiatric inpatients in Rennes, France: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:227.

Lalloo R, Kisely S, Amarasinghe H, Perera R, Johnson N. Oral health of patients on psychotropic medications: a study of outpatients in Queensland. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):338–42.

Lopes AG, Ju X, Jamieson L, Mialhe FL. Oral health-related quality of life among Brazilian adults with mental disorders. Eur J Oral Sci. 2021;129(3):e12774.

Nayak SU, Pai KK, Shenoy R. Effect of psychiatric illness on oral tissue, gingival and periodontal health among non-institutionalized psychiatric patients of Mangalore. India Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2020;22(2):45–51.

Kebede B, Kemal T, Abera S. Oral health status of patients with mental disorders in southwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39142.

Gurbuz O, Alatas G, Kurt E, Dogan F, Issever H. Periodontal health and treatment needs among hospitalized chronic psychiatric patients in Istanbul. Turkey Community Dental Health. 2011;28(1):69–74.

Tani H, Uchida H, Suzuki T, Shibuya Y, Shimanuki H, Watanabe K, et al. Dental conditions in inpatients with schizophrenia: A large-scale multi-site survey. BMC Oral Health. 2012;12:32.

Tredget J, Wai TS. Raising awareness of oral health care in patients with schizophrenia. Nurs Times. 2019;115(12):21–5.

Kuipers S, Castelein S, Barf H, Kronenberg L, Boonstra N. Risk factors and oral health-related quality of life: A case-control comparison between patients after a first-episode psychosis and people from general population. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2022;29(3):430–41.

Janardhanan T, Cohen CI, Kim S, Rizvi BF. Dental care and associated factors among older adults with schizophrenia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(1):57–65.

Nielsen J, Munk-Jorgensen P, Skadhede S, Correll CU. Determinants of poor dental care in patients with schizophrenia: a historical, prospective database study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):140–3.

Yoshii H, Kitamura N, Akazawa K, Saito H. Effects of an educational intervention on oral hygiene and self-care among people with mental illness in Japan: a longitudinal study. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:81.

Aromataris E, Munn Z. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer's manual. Australia 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for qualitative research. 2017. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for analystical cross sectional studies. 2017. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for cohort studies. 2017. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for randomized controlled trials. 2017. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for case control studies. 2017. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

Goldsmith MR, Bankhead CR, Austoker J. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative research in evidence-based patient information. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(3):262–70.

Poudel P, Griffiths R, Wong VW, Arora A, Flack JR, Khoo CL, et al. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and care practices of people with diabetes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):577.

Sanchez P, Everett B, Salamonson Y, Redfern J, Ajwani S, Bhole S, et al. The oral health status, behaviours and knowledge of patients with cardiovascular disease in Sydney Australia: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):12.

Zimmermann H, Zimmermann N, Hagenfeld D, Veile A, Kim T-S, Becher H. Is frequency of tooth brushing a risk factor for periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43(2):116–27.

Kumar S, Tadakamadla J, Johnson NW. Effect of Toothbrushing Frequency on Incidence and Increment of Dental Caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Dent Res. 2016;95(11):1230–6.

Acharya R, George A, Ng Chok H, Maneze D, Blythe S. Exploring the experiences of foster and kinship carers in Australia regarding the oral healthcare of children living in out-of-home care. Adopt Foster. 2022;46(4):466–76.

Faulks D. Evaluation of a long-term oral health program by carers of children and adults with intellectual disabilities. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20(5):199–208.

Manchery N, Subbiah GK, Nagappan N, Premnath P. Are oral health education for carers effective in the oral hygiene management of elderly with dementia? A systematic review Dental Research Journal. 2020;17(1):1–9.

Hansen C, Curl C, Geddis-Regan A. Barriers to the provision of oral health care for people with disabilities: BDJ In Pract. 2021;34(3):30–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41404-021-0675-x. Epub 2021 Mar 8 2021

Prasad R, Edwards J. Removing Barriers to Dental Care for Individuals With Disability. Prim Dent J. 2020;9(2):62–73.

Acknowledgements

WSU University librarians for assistance with search strategy.

Funding

Nil funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived and designed the study. AMJ developed the search strategy and conducted the literature search and initial screening assessment. The second screening of the articles were reviewed by AG, AK, LR, TR and quality assessment was undertaken by AMJ, TR and LR. AMJ and AG completed data synthesis and interpretations and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. AK, LR, TR and AG provided input into versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, A.M., Kenny, A., Ramjan, L. et al. Oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of people living with mental illness: a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Public Health 24, 2263 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19713-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19713-1