Abstract

Background

An important complication of pyogenic spondylitis is aneurysms in the adjacent arteries. There are reports of abdominal aortic or iliac aneurysms, but there are few reports describing infected aneurysms of the vertebral artery. Furthermore, there are no reports describing infected aneurysms of the vertebral arteries following cervical pyogenic spondylitis. We report a rare case of an infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery as a complication of cervical pyogenic spondylitis, which was successfully treated by endovascular treatment.

Case presentation

Cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 59-year-old man who complained of severe neck pain showed pyogenic spondylitis. Although he was treated extensively by antibiotic therapy, his neck pain did not improve. Follow-up MRI showed the presence of a cyst, which was initially considered an abscess, and therefore, treatment initially included guided tapping and suction under ultrasonography. However, under ultrasonographic examination an aneurysm was detected. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed an aneurysm of the vertebral artery. Following endovascular treatment (parent artery occlusion: PAO), the patient’s neck pain disappeared completely.

Conclusion

Although there are several reports of infected aneurysms of the vertebral arteries, this is the first report describing an infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery as a result of cervical pyogenic spondylitis.

Whenever a paraspinal cyst exist at the site of infection, we recommend that clinicians use not only X-ray, conventional CT, and MRI to examine the cyst, but ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced CT as well because of the possibility of an aneurysms in neighboring blood vessels. It is necessary to evaluate the morphology of the aneurysm to determine the treatment required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

The number of patients being hospitalized because of pyogenic spondylitis is increasing annually [1]. Abscesses may result from pyogenic spondylitis. Although an aneurysm at an adjacent artery is one of the important complications associated with pyogenic spondylitis, aneurysms might be misdiagnosed as abscesses. There have been reports of abdominal aortic or iliac aneurysms following pyogenic spondylitis [2,3,4,5,6]; however, no reports describing infected aneurysms of the vertebral arteries following cervical pyogenic spondylitis exist. We report a rare case of an infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery following cervical pyogenic spondylitis, which was successfully managed with endovascular treatment.

Case presentation

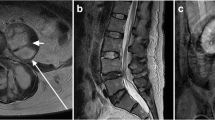

A 59-year-old man with a medical history of dyslipidemia was suffering from continuous neck pain. Three days after the appearance of neck pain, he visited a nearby clinic and was treated conservatively using analgesics only. Two weeks later, he was referred to another hospital because of a high fever of 38.6° C and increased inflammatory markers on a blood examination [C-reactive protein (CRP) was 31.55 mg/dl and white blood cell (WBC) count was 31,000/µl]. He was hospitalized on the same day (day 0) because magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed cervical pyogenic spondylitis and an extradural abscess at C6 and C7 (Fig. 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging performed on initial hospitalization at the referring hospital.

a T2-weighted sagittal image revealed a high intensity lesion at the C6/C7 vertebral body (arrow), retropharyngeal space, and epidural space (arrowhead). The epidural lesion had compressed the dural sac from the ventral side

b T2-weighted axial image at C6/7 revealed a high intensity lesion at the epidural space (arrowhead) that had compressed the dural sac from the ventral side

He was treated with a combination of antibiotics including vancomycin and cefazolin and provided with a cervical collar. Staphylococcus aureus was detected in the blood culture on day 5, and cefazolin was subsequently administered. The inflammation improved and tests performed on day 17 showed CRP of 3.86 mg/dl and WBC count of 5700/µl. However, the patient reported that their neck pain had worsened and follow-up MRI on day 17 indicated the presence of a cyst at the retropharyngeal space adjacent to the infected vertebral body (Fig. 2). The patient was then transferred to our hospital for further treatment on day 20.

Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging performed at referring hospital

a T2 weighted parasagittal image at left side revealed a cyst at C6/C7 level (arrow)

b T2-weighted axial image revealed a cyst at the retropharyngeal space, adjacent to the infected vertebral body (arrow). Dural sac compression by the epidural abscess remained (arrowhead)

Once he had been transferred, his body temperature was recorded at 37.7 ° C and the rest of his vital signs were normal. CRP was 5.03 mg/dl and WBC count was 7400/µl. He felt severe neck pain with a visual analogue scale (VAS) score of 8.0. Physical examination revealed muscle weakness at the bilateral finger extension. There was no evidence of pyramidal signs or sensory disturbance.

An ultrasonographic examination of the neck was performed in order to evaluate the properties of the neck cyst (which was thought to be an abscess). Ultrasonographic examination showed pulsatile turbulence in the cyst (Fig. 3a). Color Doppler ultrasonography showed blood flow inside the cyst, which was linked to the vertebral artery (Fig. 3b and c). Therefore, we suspected the cyst to be a vertebral aneurysm and performed contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) for confirmation. The contrast-enhanced CT scans showed blood flow to the cyst from the vertebral artery; therefore, the cyst, initially thought to be an abscess, was diagnosed as an infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery (Fig. 4). The patient underwent endovascular treatment (parent artery occlusion; PAO) at our department of Neurosurgery (Fig. 5) and his neck pain subsequently disappeared completely (VAS was 0).

He was transferred back to the referring hospital on day 47 without complications resulting from the treatment. Cefazolin was administered to the patient until day 58, after which cefaclor was orally administered until day 91 (as an outpatient). CRP was 0.02 mg/dl and WBC count was 4600/µl in a blood examination performed on day 91. When the antibiotic therapy was finished, his muscle weakness recovered and his VAS for neck pain remained 0. The C5-C6 vertebral body was completely fused. At the 2-year follow-up, there were no new lesions or recurrence of the pyogenic spondylitis or aneurysm.

Discussion

Most incidences of pyogenic spondylitis are reported as bloodstream infections that often infect intervertebral discs [7]. Our case did not result from iatrogenic conditions or an underlying disease, thus, the route of infection was unknown. For pyogenic spondylitis, a biopsy is recommended to determine the responsible bacteria [8]. Initially, biopsy and drainage were recommended because of the presence of a cyst in our case, which thought to be an abscess. Generally, CT-guided or fluoroscopy-guided biopsy is performed for pyogenic spondylitis [9]. In our case, we planned ultrasound-guided biopsy because the cyst and vessels were not deeply located and could be easily detected by ultrasonography in real time. Ultrasonographic findings revealed that the cyst (initially thought to be an abscess) was actually an aneurysm of the vertebral artery.

Although there are reports of infected aneurysms, a limited number of reports have described infected aneurysms of the vertebral arteries as indicated in Table 1 [10,11,12,13]. Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first report describing an infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery due to cervical pyogenic spondylitis. The first infected aneurysm was reported by Osler [14], which had been caused by invasion of the arterial wall by bacteria and its destruction by neutrophils.

Infected aneurysms are broadly classified into those arising from infection of arterial walls and the infection of existing aneurysms. The routes of infections of arterial walls are further classified into four categories: (1) infected endocarditis [14], (2) adjacent infected lesions [15], (3) bloodstream infection due to a damaged vascular intima [16], (4) infection due to trauma [17]. The route of infection in our case was considered to be the adjacent infected lesion.

In previous reports, the diagnosis of an infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery was confirmed by conventional and contrast-enhanced CT. An aneurysm may be diagnosed by palpation, but this was difficult in our case because the common carotid artery was in close proximity to the aneurysm. Therefore, we confirmed that the cyst (which was initially thought to be an abscess) was an aneurysm by ultrasonographic examination, which is a non-invasive and convenient procedure. Furthermore, contrast-enhanced CT scans showed that the cyst was an aneurysm of the vertebral artery. MRI is generally considered the most sensitive method for examination of pyogenic spondylitis [18]. In our case, during the follow-up consultation, monitoring of the pyogenic spondylitis was performed by MRI and X-ray photography. Since the spine is adjacent to blood vessels, it is difficult to distinguish whether a paraspinal cyst is an abscess or aneurysm. Therefore, it is necessary to exclude aneurysms by ultrasonographic examination or contrast-enhanced CT when a paraspinal cyst is observed, even if the cyst is thought to be an abscess.

The treatment for infected aneurysms of the vertebral arteries, includes surgical treatments for ruptured cases and large aneurysms [10, 11]. In addition, endovascular treatments have been reported for saccular aneurysms [13], and conservative treatment has been reported for asymptomatic fusiform aneurysms [12]. According to the literature, surgery is recommended for ruptured cases and large aneurysms of vertebral artery. When deciding on the management strategy of unruptured aneurysms of the vertebral artery, adopting a treatment strategy similar to that of cerebral aneurysms is desirable. Conservative treatment is indicated for aneurysms with a diameter ≤ 5 mm or ≤ 7 mm, while surgery is recommended for larger aneurysms [19, 20]. Infected aneurysms are particularly more likely to expand or rupture and require aggressive surgery [21]. In terms of aneurysm morphology, it has been reported that saccular aneurysms have a higher risk of rupture than fusiform aneurysms [22], and high-risk saccular aneurysms can be detected by determining their aspect ratio [23, 24]. In addition, if clinical symptoms suggestive of imminent rupture are present, such as pain, or if the diameter of the aneurysm increases rapidly, urgent surgery is required. In summary, we believe that safe, conservative treatment of infected aneurysms of vertebral artery are only possible for small, asymptomatic, fusiform aneurysms. Aneurysms with a diameter of 5 mm or less are particularly good candidates for conservative treatment. Even when electing conservative treatment, it is necessary to perform CT or ultrasonographic follow-up with strict antihypertensive control and be aware of whether the aneurysm diameter has expanded. Before surgery, it is necessary to check the dominant side of the vertebral artery and determine the presence of anomalies such as posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) termination, which is reportedly found in 0.04–1.3% of cases [25,26,27]. If there is a risk of cerebral infarction due to embolization of the vertebral artery on the side of the aneurysm, occipital artery-PICA bypass or endovascular treatment with a stent should be performed. Since endovascular modalities are developing rapidly, even ruptured aneurysms and aneurysms that require revascularization may be managed endovascularly, except in cases where endovascular treatment is technically difficult or when there are concerns about placing a prosthetic device at the infected site. In the current case, the patient suffered from severe neck pain, and we suspected that rupture of a saccular aneurysm was impending. Minimally invasive endovascular treatment was thus performed. Generally, PAO or stent implantation are performed as the endovascular treatment. We selected PAO because of the sufficient blood flow from the contralateral vertebral artery and concerns about placing an artificial object at the infected site. As a result, cervical pain disappeared and a good outcome was achieved.

In conclusion, we described the treatment of an infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery following cervical pyogenic spondylitis. This report highlights the need to evaluate paraspinal cysts located around the vertebral artery using not only X-ray, conventional CT, and MRI, but also ultrasonographic examination and contrast-enhanced CT considering the possibility of an aneurysm being present. Moreover, we recommend that the morphology of the aneurysm be evaluated to determine the most effective treatment required. The cervical pain of the patient in the current study disappeared after endovascular treatment.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- PAO:

-

Parent artery occlusion

- PICA:

-

Posterior inferior cerebellar artery

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

References

Issa K, Diebo BG, Faloon M, Naziri Q, Pourtaheri S, Paulino CB, et al. The epidemiology of vertebral osteomyelitis in the United States from 1998 to 2013. Clin Spine Surg. 2018;31:E102-8.

Sugawa M, Tanaka R, Nakamura M, Isaka N, Nishimura J, Kimura M, et al. A case of infectious pseudoaneurysm of the abdominal aorta associated with infectious spondylitis due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. Jpn J Med. 1989;28:402–5.

Reddy DJ, Shepard AD, Evans JR, Wright DJ, Smith RF, Ernst CB. Management of infected aortoiliac aneurysms. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill: 1960). 1991;126:873-8; discussion 8–9.

Hagino RT, Clagett GP, Valentine RJ. A case of Pott’s disease of the spine eroding into the suprarenal aorta. J Vasc Surg. 1996;24:482–6.

Doita M, Marui T, Kurosaka M, Yoshiya S, Tsuji Y, Okita Y, et al. Contained rupture of the aneurysm of common iliac artery associated with pyogenic vertebral spondylitis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:E303-7.

Tsuji Y, Okita Y, Niwaya K, Tsukube T, Doita M, Marui T, et al. Allograft replacement of common iliac artery mycotic aneurysm caused by Bacteroides fragilis vertebral spondylitis–a case report. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2003;37:441–4.

Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, Darouiche RO, Widmer AF, Schmitt SK, et al. Infectious iseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:e26–46.

Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369–79.

Pola E, Taccari F. Multidisciplinary management of pyogenic spondylodiscitis: epidemiological and clinical features, prognostic factors and long-term outcomes in 207 patients. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:229–36.

Flye MW, Wolkoff JS. Mycotic aneurysm of the left subclavian and vertebral arteries. A complication of cervicothoracic sympathectomy. Am J Surg. 1971;122:427–9.

Singh D, Pinjala RK, Purohit AK, Reddy LR, Bhattacharjee S. Giant mycotic aneurysm of the vertebral artery: a case report. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:348–51.

Gupta T, Parikh K, Puri S, Agrawal S, Agrawal N, Sharma D, et al. The forgotten disease: Bilateral lemierre’s disease with mycotic aneurysm of the vertebral artery. Am J Med Case Rep. 2014;15:230–4.

Hashimoto K, Isaka F, Yamashita K. An infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery treated with a stent-graft: a case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015;55:852–5.

Osler W. The Gulstonian lectures, on malignant endocarditis. BMJ. 1885;1:467–70.

Hsu RB, Lin FY. Psoas abscess in patients with an infected aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:230–5.

Itatani K, Miyata T, Komiyama T, Shigematsu K, Nagawa H. An ex-situ arterial reconstruction for the treatment of an infected suprarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm involving visceral vessels. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:380–3.

Samore MH, Wessolossky MA, Lewis SM, Shubrooks SJ Jr, Karchmer AW. Frequency, risk factors, and outcome for bacteremia after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:873–7.

An HS, Seldomridge JA. Spinal infections: diagnostic tests and imaging studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:27–33.

Wermer MJ, van der Schaaf IC, Algra A, Rinkel GJ. Risk of rupture of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in relation to patient and aneurysm characteristics: an updated meta-analysis. Stroke. 2007;38:1404–10.

Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J 3rd, Meissner I, Brown RD Jr, Piepgras DG, et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003;362:103–10.

Rakita D, Newatia A, Hines JJ, Siegel DN, Friedman B. Spectrum of CT findings in rupture and impending rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Radiographics. 2007;27:497–507.

Nathan DP, Xu C, Pouch AM, Chandran KB, Desjardins B, Gorman JH 3rd, et al. Increased wall stress of saccular versus fusiform aneurysms of the descending thoracic aorta. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25:1129–37.

Akai T, Hoshina K, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi H, Nemoto Y, Ohshima M, et al. Biomechanical analysis of an aortic aneurysm model and its clinical application to thoracic aortic aneurysms for defining “saccular” aneurysms. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001547.

Natsume K, Shiiya N, Takehara Y, Sugiyama M, Satoh H, Yamashita K, et al. Characterizing saccular aortic arch aneurysms from the geometry-flow dynamics relationship. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:1413–120.

OʼDonnell CM, Child ZA, Nguyen Q, Anderson PA, Lee MJ. Vertebral artery anomalies at the craniovertebral junction in the US population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:E1053-7.

Fortuniak J, Bobeff E, Polguj M, Kośla K, Stefańczyk L, Jaskólski DJ. Anatomical anomalies of the V3 segment of the vertebral artery in the Polish population. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:4164–70.

Wakao N, Takeuchi M, Nishimura M, Riew KD, Kamiya M, Hirasawa A, et al. Vertebral artery variations and osseous anomaly at the C1-2 level diagnosed by 3D CT angiography in normal subjects. Neuroradiology. 2014;56:843–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TF was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. MK conceived the report and helped to draft the manuscript. MK, HS, MT, SK, and YY examined and treated the patient. AO, YS and YY collected and organized the patient’s data. HS and YT supervised to wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Formal approval is not required for this type of study. Moreover, the need for informed consent to participate was waived.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Furukawa, T., Masuda, K., Shigematsu, H. et al. An infected aneurysm of the vertebral artery following cervical pyogenic spondylitis: a case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22, 22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03881-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03881-3