Abstract

Purpose

Continuing professional development (CPD) is an approach for health professionals to preserve and expand their knowledge, skills, and performance, and can contribute to improving delivery of care. However, evidence indicates that simply delivering CPD activities to health professionals does not lead to a change in practice.

This review aimed to collate, summarize, and categorize the literature that reported the views and experiences of health professionals on implementing into practice their learning from CPD activities.

Methods

This review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual methodology for scoping reviews. Three databases, PubMed, Embase and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), were systematically searched in February 2023 for articles published since inception. Two independent reviewers screened the articles against the inclusion criteria, and completed the data extraction. Data were summarized quantitatively, and the findings relating to views and experiences were categorized into challenges and facilitators.

Results

Thirteen articles were included. Implementation of learning was not the primary focus in the majority of studies. Studies were published between 2008-2022; the majority were conducted in North America and nurses were the most common stakeholder group among Healthcare Professionals (HCPs). Five studies adopted qualitative methods, four quantitative studies, and four mixed-methods studies. The reported barriers of implementation included lack of time and human resource; the facilitators included the nature of the training, course content and opportunity for communal learning.

Conclusion

This review highlights a gap in the literature. Available studies indicate some barriers for health professionals to implement their learning from CPD activities into their practice. Further studies, underpinned with appropriate theory and including all relevent stakeholders are required to investigate strategies that may facilitate the integration of learning from CPD into routine practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Continuing professional development (CPD) refers to the ongoing process through which healthcare professionals partake in activities aimed at preserving and expanding their knowledge, skills, and performance [1, 2]. It also involves cultivating the personal and professional attributes necessary for delivering safe and effective services, ultimately with the aim of optimizing care for the improvement of community health [3,4,5].

The requirement to complete an ascribed number of CPD hours on an annual basis has been adopted by licensing and regulatory bodies across various health professional bodies around the world, including those in the United Kingdom, United States, Canada and New Zealand [6,7,8,9].

Systematic and coordinated planning is fundamental in the development of CPD activities; adult learning principles of autonomy, self-directed, goal-orientated, and practice-based learning should serve as the blueprint for CPD design [10, 11]. Further, the four stages of CPD learning process provides a framework for clinicians to prioritize and measure the success of CPD activities: review; plan; implement; and evaluate and reflect [12]. The review and planning stages often involve a self-directed assessment of individual performance, skill and knowledge in the context of one’s own practice (and likely future practices), and then to identify specific learning needs and the necessary learning activities to address those needs [12, 13]. The implementation stage entails integrating the skills/knowledge attained from the learning activity into one’s routine clinical practice [12]; and has been defined more specifically as the process by which learning is put into practice, connecting research and evidence directly to actions within one’s practice, this includes application of new learning to improve outcomes within one’s own setting [14]. The final stage involves evaluation and reflection on the impact of the learning activity on the service delivery [12, 15].

All stages of the CPD learning process are challenged by many factors that act as barriers that should be addressed for successful learning and subsequent positive impacts within the healthcare system [16,17,18,19]. The reported positive impacts from CPD are numerous, indeed a 2019 scoping review categorizing the broad impacts of CPD identified 12 categories including knowledge, practice change, skill, confidence, attitudes, career development, networking, user outcomes, intention to change, organizational change, personal change and scholarly accomplishments [15]. Achieving these impacts are by no means guaranteed, even though significant economic costs and resources are invested in the design and delivery of CPD programs to support achieving the intended goals [20,21,22]. Therefore, in the current challenging times for healthcare delivery, with regards to economic constraints and workforce shortages, it is essential that each stage of the CPD learning process is comprehensively evaluated and optimized to enhance the effectiveness of CPD.

Published reviews have focused on the evaluation of CPD programs [23,24,25,26], but a preliminary search of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted and no current or underway systematic reviews or scoping reviews on the implementation of learning from CPD activities were identified.

Implementation, in the context of healthcare interventions, refers to the extent to which health interventions can be effectively integrated within real-world public health and clinical service systems [27]. There is an increasing number of studies focussing on investigating the factors influencing the implementation of new interventions in healthcare, often utilizing implementation theories and frameworks to guide research [28,29,30,31,32]. One such framework that has gained prominence is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [33], utilized in multiple implementation studies [34,35,36,37,38,39].

CFIR provides a structured approach to identifying and understanding the factors that influence the implementation of innovations in healthcare. It categorizes these factors into five key domains: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and processes [33]. By using CFIR, researchers can systematically explore the complexities of implementing changes in practice, such as those arising from CPD learning, and identify barriers and facilitators to successful integration.

Given the growing recognition of the importance of implementation science in healthcare and evidence suggesting that knowledge alone does not necessarily lead to changes in clinical practice [40], there is a critical need to better understand how learning from CPD activities is actually put into practice. Investigating the implementation of learning is essential for identifying the factors that enable or hinder the translation of knowledge into actionable changes in clinical settings. This understanding is crucial for optimizing CPD programs to ensure that the time, effort, and resources invested in professional development lead to tangible improvements in healthcare delivery and patient outcomes.

This review aims to collate, summarize, and categorize the literature reporting on the experiences of healthcare professionals in implementing learning from CPD activities, using CFIR as a guiding framework to enhance our understanding of these processes.

Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to collate, summarize, and categorize the literature that reported investigating the views and experiences of healthcare professionals’ on implementing into practice their learning from CPD activities.

Methods

This scoping review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewers’ Manual methodology for scoping reviews [41] and was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [42]. The study protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework database (Registration number: 4se2c).

Eligibility criteria

The review included published studies answering the following research question (based on the Population/Concept/Context): What does the literature report regarding health professionals’ views and experiences on implementing into practice their learning from CPD activities?

Population

Studies were included if they were conducted with CPD activity participants who were registered health professional; studies conducted with students (either undergraduate or postgraduate) enrolled on academic programs were excluded.

Concept & context

Studies were included if they investigated views and/or experiences in the context of implementing learning from CPD participation into practice. Studies measuring or reporting on the impact of the CPD activity were excluded as were studies investigating the development or validation of tools to evaluate CPD activities.

Only studies published in English were included and there were no date limitations applied to the search. All study designs were considered, except for reviews. Letters, commentaries, perspectives, calls for change, and editorials were also excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

A preliminary search of PubMed was conducted to identify articles on the topic. The words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a full search strategy for the following electronic databases: PubMed, Embase and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (see Appendix 1 for full details of the search). The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms were adapted using appropriate Boolean operators AND OR combined with truncation for each of the databases. The reference lists of all included articles were also screened for additional studies. Databases were searched independently by two reviewers between February 13th and February 17th 2023.

Study/source of evidence selection

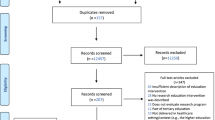

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into EndNote X8VR® and duplicates were removed. These sources were then imported into the Intelligent Systematic Review platform Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) web application [43]. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria, similarly full-text screening was then conducted by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were discussed between the two reviewers, and if necessary were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

A data extraction tool was developed to align with the aim of the review. The extracted data included date of study, country, setting, health profession group, study design, time of data collection, and reported views and experiences. The tool was piloted by two reviewers using three of the included studies. This resulted in minor refinements being made to the tool to capture further details regarding the duration of the study. Two reviewers independently completed the data extraction of the included studies. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer (Appendix 2 contains full details of the data extraction).

Data analysis and presentation

Data were summarized quantitatively and qualitatively in relation to review aim. Frequency analysis based on numerical counts of key characteristics (including healthcare professional group, setting and geographic location) were extracted and presented in tabular format. The included studies were reviewed independently by two reviewers to identify findings relating to views and experiences; these were categorized into challenges and facilitators.

Results

The database search returned 445 articles. After excluding duplicates, and screening against the aforementioned inclusion criteria, 13 articles were included in the review. (Fig. 1 presents the PRISMA-ScR flow chart of the literature search and study selection process and Appendix 2 provides further details of articles excluded following full-text review).

The following sections provide an overview and descriptive summary of the included studies.

Descriptive summary of the included studies

Table 1 provides a summary and Table 2 provides more detailed characteristics of the 13 studies included in the scoping review.

Studies were published between 2008 and 2022. Most of the studies were conducted in North America, with Canada and the USA accounting for six of the total studies.

Investigations included CPD activities targeting health professionals working in a range of settings, including primary (n = 4), secondary (n = 5) and tertiary care (n = 1). However, in three studies, the setting was not specified.

In the majority of studies, the CPD activity was delivered to an audience consisting of multiple healthcare professional (HCPs) groups (n = 8) where the reporting of views and experiences of participants were pooled together. The sample of study participants ranged considerably, from a qualitative study that included a sample of nine perioperative nurses [48], to a mixed methods study that included 222 multidiscpilanary participants attending an interprofessional diabetes champion course [52]. Nurses were the most common stakeholder group among HCPs, appearing in four of the studies. Pharmacists were the second most common group, appearing in three of the included studies. Investigations also included leaders, managers, and directors, who were participants in three studies.

Methods used to capture views and experiences

Five of the studies adopted qualitative methods for data collection, including one-to-one semi-structured interviews (n = 3) [46, 48, 54] focus groups (n = 1) [44], and descriptive analysis of participants’ written Strenghts Weaknesses Opportunities Threats (SWOT) evaluation (n = 1) [45]. There were four studies utilizing cross-sectional surveys; and a further four studies using mixed methods, of which three were of sequential explanatory design consisting of an initial quantitative survey followed by qualitative interviews [47, 52, 56], and one study consisting of analysis of medical records and semi-structured interviews [53].

In the majority of studies, implementation of learning was not the primary focus; rather it was an aspect of wider investigations, in varying extents, that were conducted with CPD participants to assess or evaluate elements of the CPD activity. A review of the specific data collection tools reveals the extent to which studies were focused on implementation of learning. In many of the cross-sectional surveys, implementation of learning was captured using 1–2 items; whereas more comprehensive investigations occurred in the qualitative studies which sought to examine indiduals’ reported barriers and facilitators of implementing learning to a greater extent.

The time after the CPD activity at which investigations took place varied across the studies. Investigations took place within one month of the CPD activity [44], between one and three months [52, 56], between four and twelve months [52, 54, 55] and between 13 and 24 months [45, 47]. In two studies, the time point for data collection was not mentioned [46, 48]. In three of the studies, investigations took place at multiple intervals after the CPD activity, attempting to explore both immediate and longer-term implementation of learning into practice [50, 52, 53]. These studies included administration of a post-activity survey immediately after the CPD activity and then, either re-administration of the survey after three months [50], or phone interviews with a sample of respondents within three months [52]. One study conducted an analysis of medical records immediately after the CPD activity to evaluate the level of participants’ implementation into learning, and these participants were then recruited to participate in focus groups six months later to investigate their views and experiences [53].

Use of theoretical models/frameworks

Five studies utilized theoretical models or frameworks within their studies, however, the context of their use was not to specifically capture implementation of learning [45, 50, 53, 55, 56]. Two studies used an evaluation framework/model: the Kirkpatrick model was used to develop a survey that aimed to evaluate participants’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the CPD activity [53]; in a separate study, the Moore’s evaluation framework was adapted to evaluate participants’ sustained performance change [55]. A behavioural frameworks was used in one study: the Theoretical Domains Framework was used to develop an interview guide in a study investigating participants views of the barriers, facilitators and perceived impact of the CPD activity [53]. One study used Wenger’s social learning theory to investigate the range of social learning impacts that are possible because of attending a CPD activity [46].

One study assessing whether implementing learning from CPD influenced HCP’s clinical behavioural intentions, developed a survey combining a number of theories including the Theory of planned behaviour and the Triandis theory [56].

Health professionals’ view and experiences

Table 3 Presents the themes and a summary of findings of included studies investigating views and experiences of health professionals’. The views and experiences of health professionals’ regarding implementation of learning into practice were categorised into: Challenges of implementing learning from CPD activities into practice; Facilitators of implementing learning from CPD activities into practice.

Discussion

Summary of key findings

This review has collated, summarized, and categorized healthcare professionals’ views and experiences regarding implementing learning from CPD activities into their practice. The work provides researchers and CPD developers insights into current practices and areas for future studies.

The key findings of this review relate to the lack of studies that set out to specifically and systematically investigate the implementation of learning from CPD activities. This was evident through the nominal focus implemenentation was afforded within included studies and by the absence of implementation theory to underpin investigations. Those studies reporting on implementation of learning focussed on highlighting the challenges, of which time and human resource were frequently reported; and to a lesser extent, the facilitators where the focus was more aligned to the nature of the training, course content and opportunity for communal learning.

Interpretation of findings

While healthcare professionals may actively participate in well-designed CPD programs, the lack of implementation-focused research hinders understanding of the extent to which learning from CPD activities is implemented and the full range of factors that are frequently implicated. This is in contrast to other aspects of CPD that have been more extensively explored and reported in systematic and scoping reviews, such as approaches to learning needs assessment to inform CPD [59], and evaluation of effectiveness of CPD activities [60,61,62].

Despite five of the included studies adopting a theoretical underpinning, there were not any studies that utilised implementation theory. The use of theory to support research in healthcare and education has been widely advocated [63,64,65,66]. It has been reported that incorporating theory enhances the comprehensiveness of investigations allowing for exploration of the complex interplay of variables and concepts [67]. Further to this, the adoption of implementation theory has the potential to elicit greater insights into the full range of factors that act as influencers of the phenomenon being examined and thus providing rich data on specific aspects that may require further refinemenet [68, 69]. Thus, it can be seen from the literature that the use of theory in intervention implementation, is more likely to result in effective and sustained interventions [70, 71].

One recent scoping review in the domain of learning health systems, which includes CPD initiatives, revealed a distinct lack of comprehensive reporting of implementation efforts, and subsequently concluded that implementation determinants are poorly understood [72]. The review also identified few studies had adopted implementation theories, models or frameworks, and thus recommend their use in future research to provide a structured approach to plan, implement, and evaluate interventions, including those in the area of training and education.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research is specifically designed to systematically assess barriers and facilitators in implementation within local settings and can guide decisions regarding the needs within a local context [73]. Other implementation frameworks include the Proctor taxonomy of implementation outcomes [74] and RE-AIM [75], and have also been applied to the health domain to evaluation implementation. To guide optimization of processes and programs, the CPD field would benefit from employing such frameworks within its processes and programs as part of the initial planning, ongoing assessment and summative evaluation.

In the relatively small number of articles to report on implementation of learning from CPD into routine practice, only three studies followed-up with CPD participants at multiple time points, the majority of studies were conducted at a single time point between 1 and 24 months after a CPD activity. This likely reflects the lack of consideration concerning assessing both the early stages of implementation which includes assessing the feasibility, appropriateness, acceptability, and adoption as well as the long-term sustainability and penetration of the learning into routine practice [76]. Nevertheless, the included studies reported on the barriers and facilitators to implementing their learning from CPD activities across different settings which can begin to inform CPD develops and health institutions to overcome barriers. Contextual factors relating to inadequate time, human resource and communication breakdowns were the most frequently cited issues. However, the complexity of the educational concepts was also a frequently reported barrier, as CPD participants often found that the learning content was not delivered in a manner that facilitated easy application into their clinical practice. A 2018 scoping review assessing the barriers and facilitators to self-directed learning in CPD fpr physicians in Canada identified similar challenges related to time restrictions, and competing demands and interests. The study also cited amongst other barriers, a shortage of academics with the required knowledge and experience in team training [77]. Understanding these challenges is essential to enhancing the potential benefits from CPD programs and subsequently result in sustainable improvements in health care delivery.

In the few studies reporting potential facilitators, comprehensive training and training materials was most frequently mentioned. This finding underscores the need for integrating established learning pedagogies, particularly adult learning principles such as those proposed by Knowles, into the design and delivery of CPD programs [8, 78, 79]. Knowles’ principles, which emphasize self-directed learning, relevance, practical application, and the immediate utility of new knowledge, are crucial for creating CPD experiences that lead to discrete and actionable learning outcomes. Greater consideration and integration of these principles can enhance the effectiveness of CPD activities by making them more relevant and directly applicable to healthcare professionals’ daily practices.

A valuable resource in this context is a published quick guide for health professional educators on the use of adult learning theories, which provides an overview of various adult learning theories and their potential application in healthcare education [11]. This guide highlights the importance of aligning educational practices with learning theories, advocating for a deliberate connection between how CPD is designed and the adult learning needs of participants. Using such resources can significantly enhance the impact of CPD by fostering more engaging, relevant, and effective learning experiences that are directly translatable into practice.

It is important to note that the majority included studies originated from the United States and Canada; the implementation of learning from CPD and the priority that CPD is afforded within health systems across the world is likely to vary significantly. Therefore, the relevance and transferability of these findings to other contexts may be constrained.

Strengths and limitations

While previous reviews have explored various aspects of CPD, this scoping review is the first to specifically examine the implementation of learning from CPD activities into practice. This focus on the practical application of CPD learning distinguishes our review from others that primarily assess the efficacy or outcomes of CPD programs.

A key strength of this work is the comprehensiveness of the search. In order to capture all relevant findings, studies were included that may have implicitly reported on implementation of learning. (A summary of the studies where the full text was reviewed and the reasons for exclusion is presented in Appendix 2). The heterogeneity of the retrieved studies presented challenges in synthesizing the findings, therefore where reviewers suspected that study findings were lacking clarity or could be misinterpreted, they were discussed between themselves in the context of the wider investigation.

However, the findings of this review are limited by the focus on studies conducted predominantly in North America, which may limit the generalizability to other healthcare systems. A wider selection of databases, such as ERIC, may have yielded further relevant studies. Similarly, incorporating grey literature, forward citation searches, and not restricting articles to English-language only, may have limited the scope of captured studies.

Further research and recommendations

This review raises the important question of why there are so few studies reporting the perspectives and experiences of health care professionals regarding the implementation of CPD in practice, despite the importance of the recent CPD literature for CPD development and design. To answer this query accurately and comprehensively, further multistakeholder investigations should be conducted and supported with relevant implementation theory, such as the CFIR. Furthermore, longitudinal studies, such as those conducted within health services research [80, 81], should be considered to elucidate issues that occur both at the early and later stages of implementation, thus providing insights that can inform sustained use of learning from CPD activities.

Additionally, CPD organizers should consider periodic follow-up evaluations to assess long-term outcomes and address barriers such as time constraints, lack of resources, and institutional support. These strategies can help ensure that CPD activities lead to meaningful changes in clinical practice.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Sargeant J, Wong BM, Campbell CM. CPD of the future: a partnership between quality improvement and competency-based education. Med Educ. 2018;52(1):125–35.

Sherman LT, Chappell KB. Global perspective on continuing professional development. Asia Pac Scholar. 2018;3(2):1.

Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? Jama. 1999;282(9):867–74.

AHPRA AHPRA. Continuing professional development. Melbourne: AHPRA; 2016. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/Registration/Registration-Standards/CPD.aspx. Updated 2016 SEP; cited 2023 May.

Filipe HP, Mack HG, Golnik KC. Continuing professional development: progress beyond continuing medical education. Ann Eye Sci. 2017;2(7):46.

HCPC HCPC. What are our standards for continuing professional development? 2018. https://www.hcpc-uk.org/registration/.

ACPE ACfPE. Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Provider program: Intranet. 2021. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/continuing-professional-development/.

Rouse MJ. Continuing professional development in pharmacy. Am J Health-System Pharm. 2004;61(19):2069–76.

Gazzard J. Continuing professional development (CPD). How to develop your healthcare career: A guide to employability and professional development. 2016;8:54–72.

Ramani S, McMahon GT, Armstrong EG. Continuing professional development to foster behaviour change: from principles to practice in health professions education. Med Teach. 2019;41(9):1045–52.

Mukhalalati BA, Taylor A. Adult learning theories in context: a quick guide for healthcare professional educators. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519840332.

Thompson D. International handbook on the continuing professional development of teachers. British J Educ Psychol. 2005;75:515.

Filipe HP, Silva ED, Stulting AA, Golnik KC. Continuing professional development: best practices. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21(2):134–41.

Hall GE, Hord SM, Aguilera R, Zepeda O, von Frank V. Implementation: learning builds the bridge between research and practice. Learn Prof. 2011;32(4):52.

Goodall J, Day C, Lindsay G, Muijs D, Harris A. Evaluating the impact of continuing professional development. UK: Department for Education and Skills; 2005.

Ward J, Wood CJE. Education and training of healthcare staff: the barriers to its success. 2000;9(2):80–5.

Ikenwilo D, Skåtun DJHP. Perceived need and barriers to continuing professional development among doctors. 2014;117(2):195–202.

Bwanga O. Barriers to continuing professional development (CPD) in radiography: a review of literature from Africa. Health Prof Educ. 2020;6(4):472–80.

Donyai P, Herbert RZ, Denicolo PM, Alexander AM. British pharmacy professionals’ beliefs and participation in continuing professional development: a review of the literature. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(5):290–317.

Brown CA, Belfield CR, Field SJ. Cost effectiveness of continuing professional development in health care: a critical review of the evidence. Bmj. 2002;324(7338):652–5.

Vaughn HT, Rogers JL, Freeman JK. Does requiring continuing education units for professional licensing renewal assure quality patient care? Health Care Manager. 2006;25(1):78–84.

Orlik W, Aleo G, Kearns T, Briody J, Wray J, Mahon P, et al. Economic evaluation of CPD activities for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2022;56(10):972–82.

Davis D, O’Brien MAT, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey AJJ. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? Jama. 1999;282(9):867–74.

Phillips JL, Heneka N, Bhattarai P, Fraser C, Shaw T. Effectiveness of the spaced education pedagogy for clinicians’ continuing professional development: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2019;53(9):886–902.

Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(2):131–8.

Forsetlund L, Eike MC, Gjerberg E, Vist GE. Effect of interventions to reduce potentially inappropriate use of drugs in nursing homes: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):16.

Spiegelman D. Evaluating public health interventions: 1. Examples, definitions, and a personal note. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):70–3.

Birken SA, Powell BJ, Presseau J, Kirk MA, Lorencatto F, Gould NJ, et al. Combined use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the theoretical domains Framework (TDF): a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):2.

Means AR, Kemp CG, Gwayi-Chore MC, Gimbel S, Soi C, Sherr K, et al. Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15:1–9.

Ross J, Stevenson F, Lau R, Murray. Factors that influence the implementation of e-health: a systematic review of systematic reviews (an update). EJIs. 2016;11(1):1–12.

Lewis CC, Boyd MR, Walsh-Bailey C, Lyon AR, Beidas R, Mittman B, et al. A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implement Sci. 2020;15:1–25.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:1–20.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1): 50.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2015;11:1–3.

Williams EC, Johnson ML, Lapham GT, Caldeiro RM, Chew L, Fletcher GS, et al. Strategies to implement alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: a structured literature review. 2011;25(2):206.

Nevedal AL, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, Jackson GL, Cutrona SL, White BS, Damschroder LJ. Rapid versus traditional qualitative analysis using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):67.

Nazar ZJ, Nazar H, White S, Rutter P. A systematic review of the outcome data supporting the healthy living pharmacy concept and lessons from its implementation. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3): e0213607.

Khayyat SM, Nazar Z, Nazar H. A study to investigate the implementation process and fidelity of a hospital to community pharmacy transfer of care intervention. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12): e0260951.

Stewart D, Pallivalapila A, Thomas B, Hanssens Y, El Kassem W, Nazar Z, et al. A theoretically informed, mixed-methods study of pharmacists’ aspirations and readiness to implement pharmacist prescribing. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(6):1638–50.

Mansouri M, Lockyer JJJ. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. 2007;27(1):6–15.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Reviews. 2016;5:1–10.

Ghandehari OO, Hadjistavropoulos T, Williams J, Thorpe L, Alfano DP, Bello-Haas VD, et al. A controlled investigation of continuing pain education for long-term care staff. 2013;18(1):11–8.

Manzini F, Diehl EE, Farias MR, Dos Santos RI, Soares L, Rech N, Lorenzoni AA, Leite SN. Analysis of a blended, inservice, continuing education course in a public health system: lessons for education providers and healthcare managers. Front Public Health. 2020;8:561238.

Allen LM, Hay M, Armstrong E, Palermo CJMT. Applying a social theory of learning to explain the possible impacts of continuing professional development (CPD) programs. 2020;42(10):1140–7.

Reis T, Faria I, Serra H, Xavier M. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a continuing medical education intervention in a primary health care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):638.

Abebe L, Bender A, Pittini R. Building the case for nurses’ continuous Professional Development in Ethiopia: a qualitative study of the Sick Kids-Ethiopia Paediatrics Perioperative Nursing Training Program. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(5):607–14.

Young LJ, Newell KJ. Can a clinical continuing education course change behavior in dental hygiene. J Dent Hyg. 2008;82(4):33-.

Lawton A, Manning P, Lawler F. Delivering information skills training at a health professionals continuing professional development conference: an evaluation. Health Info Libr J. 2017;34(1):95–101.

Adams SG, Pitts J, Wynne JE, Yawn BP, Diamond EJ, Lee S, Dellert E, Nicola A. Hanania. Effect of a primary care continuing education program on clinical practice of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: translating theory into practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:862–870.

Beckman D, Wardian J, Sauerwein TJ, True MW. Evaluation of an Interprofessional continuing professional development course on comprehensive diabetes care: A Mixed-Methods approach. J Evaluation Clin Pract. 2019;25(1):148–54.

Safe M, Wittick P, Philaketh K, Manivong A, Gray A. Mixed-methods evaluation of a continuing education approach to improving district hospital care for children in Lao PDR. Trop Med Int Health. 2022;27(3):262–70.

Olson AK, Babenko-Mould Y, Tryphonopoulos PD, Mukamana D, Cechetto DF. Nurses’ and nurse educators’ experiences of a Pediatric Nursing Continuing Professional Development program in Rwanda. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2022;19(1):20210155.

Ivanova A, Baliunas D, Ahad S, Tanzini E, Dragonetti R, Fahim M, et al. Performance change in treating tobacco addiction: an online, interprofessional, facilitated continuing education course (TEACH) evaluation at Moore’s level 5. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2021;41(1):31–8.

Légaré F, Freitas A, Turcotte S, Borduas F, Jacques A, Luconi F, et al. Responsiveness of a simple tool for assessing change in behavioral intention after continuing professional development activities. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0176678.

Abebe L, Bender A, Pittini R. Building the case for nurses’ continuous professional development in Ethiopia: a qualitative study of the Sick Kids-Ethiopia Paediatrics Perioperative Nursing Training Program. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(5):607–14.

Marinopoulos S, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, Wilson L, Ashar B, Magaziner J, et al. Effectiveness of Continuing Medical Education. Evid report/technology Assess. 2007;149:1–69.

Al-Ismail MS, Naseralallah LM, Hussain TA, Stewart D, Alkhiyami D, Abu Rasheed HM, et al. Learning needs assessments in continuing professional development: a scoping review. Med Teach. 2023;45(2):203–11.

Allen LM, Palermo C, Armstrong E, Hay M. Categorising the broad impacts of continuing professional development: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2019;53(11):1087–99.

Firmstone VR, Elley KM, Skrybant MT, Fry-Smith A, Bayliss S, Torgerson CJ. Systematic review of the effectiveness of continuing dental professional development on learning, behavior, or patient outcomes. J Dental Educ. 2013;77(3):300–15.

Samuel A, Cervero RM, Durning SJ, Maggio LA. Effect of continuing professional development on health professionals’ performance and patient outcomes: a scoping review of knowledge syntheses. Acad Med. 2021;96(6):913–23.

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Theory, research, and practice in health behavior and health education. 2008.

Simons-Morton B, McLeroy K, Wendel M. Behavior theory in health promotion practice and research. US: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2012.

MacFarlane A, O’Reilly-de Brún M. Using a theory-driven conceptual framework in qualitative health research. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(5):607–18.

Nigg CR, Allegrante JP, Ory M. Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: common themes advancing health behavior research. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(5):670–9.

Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. US: Sage publications; 2017.

Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):189.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):53.

Green J. The role of theory in evidence-based health promotion practice. Health Educ Res. UK. 2000;15(2):125–9.

Corley KG, Gioia DA. Building theory about theory building: what constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad Manage Rev. 2011;36(1):12–32.

Ellis LA, Sarkies M, Churruca K, Dammery G, Meulenbroeks I, Smith CL, et al. The Science of Learning Health Systems: scoping review of empirical research. JMIR Med Inf. 2022;10(2):e34907.

Proctor EK, Bunger AC, Lengnick-Hall R, Gerke DR, Martin JK, Phillips RJ, et al. Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2023;18(1):31.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2011;38:65–76.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7.

Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J, Hughes G, Hinder S, et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Int Res. 2017;19(11):e8775.

Jeong D, Presseau J, ElChamaa R, Naumann DN, Mascaro C, Luconi F, et al. Barriers and facilitators to Self-Directed Learning in Continuing Professional Development for Physicians in Canada: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2018;93(8):1245–54.

Dopp AL, Moulton JR, Rouse MJ, Trewet CB. A five-state continuing professional development pilot program for practicing pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2): 28.

Johnson N, Davies D. Continuing professional development. In: Carter Y, editor. Medical education and training. From theory to delivery. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 157–70.

Neale B. Qualitative longitudinal research: Research methods. UK: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2020.

Calman L, Brunton L, Molassiotis A. Developing longitudinal qualitative designs: lessons learned and recommendations for health services research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:14.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ZN: Conception of study, design of the work, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript writing. HAO: Conception of study, design of the work, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript writing.DS: Conception of study, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript writing. AS: Conception of study, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Omary, H., Soltani, A., Stewart, D. et al. Implementing learning into practice from continuous professional development activities: a scoping review of health professionals’ views and experiences. BMC Med Educ 24, 1031 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06016-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06016-7