Abstract

Background

In patient safety accidents, nurse managers are indirectly victimized by the pressures from many aspects and become the second victim. This study delves into the experiences of nurse managers in China, aiming to uncover their cognition and provide reference for relevant managers.

Methods

A descriptive phenomenological approach was used to gain insight into the inner reality of nurse leaders’ experiences and management perceptions of experiencing patient safety incidents. The data of 15 nurse leaders who experienced patient safety incidents in Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Province, China, were collected via face‒to‒face semi-structured interviews, and the data were analyzed via the 7-step analysis method of Colaizzi.

Results

On the basis of the content of the interviews, three themes were identified, the emotional experience of experiencing patient safety events, role dilemmas, the obstruction and conceptual reshaping of nursing management. Eight subthemes as follows: physical and mental health-related symptoms due to passive coping and life and work disorder, self-relief, playing multiple roles with lack of role adjustment ability, blurred role positioning and initial signs of job burnout, event replay is impeded, Inaccurate analysis of safety incidents, subversion and remolding of the nursing management concept. Finally, it can be abstracted as “forced growth in patient safety events”.

Conclusion

Patient safety incidents can lead to negative impacts, role dilemmas, and management confusion for head nurses, but they also promote purposeful rumination, meditation, and growth. Medical institutions should pay attention to special groups that are second victims of head nurses and construct a safety event support system for nurse leaders to improve the post-training and education system for nurse leaders, help them better adapt to their roles, break through their role dilemmas, improve their post-competence, and construct an effective safety event management system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Patient safety events are unintended, potentially dangerous, for patients in healthcare facilities and affect groups such as patients and families, medical staff, and healthcare organizations [1] Scholar WU [2] first referred to patients and families who were harmed in a safety event as the first victims in 2000 and then referred to healthcare workers who were traumatized by the experience associated with the event as the second victims. Scott [3] further refined the definition of a second victim in 2009: healthcare workers who are physically and psychologically harmed by unanticipated adverse events, medical errors, or attempted events can also become second victims. A cross-sectional survey conducted by Chinese scholars Huang et al. [4] in 2021 among 6,400 nurses in six tertiary hospitals in mainland China revealed that 45.26% of the nurses had experienced at least one adverse event accompanied by psychological distress, similar to the findings of foreign scholars, who reported that more than 50% of nurses had a second victim experience [5], and studies have shown that nurses’ excessive vigilance for more than 6 months reached 23.6% [6]. Research has shown that domestic and foreign research has focused on second victims, mainly nurses and doctors [7]. Among these individuals, nurses are considered the main high-risk group [8], and related research has focused on the construction of peer support strategies, psychological experiences, support needs, and influencing factors [9,10,11,12]. Moreover, little attention has been given to head nurse patient safety incidents and the management of cognition-related research. Despite the continuous promotion of nonpunitive reporting of adverse events in recent years, the traditional punitive culture of hospitals and the condemnation of higher leaders have led to an unpromising environment for the nonpunitive reporting of adverse events [13,14,15,16]. After the occurrence of adverse events, nurse managers need to bear the concern of condemnation from the nursing leadership and face an increased workload due to the layers of analyzing the event. Moreover, managers also need to pacify the patient and the family, address the additional nursing problems caused by the event, address the relationship between the nurse party and the patient and the family, and help the party overcome difficulties. Mintzberg’s theory of managerial roles [17] categorizes the work of managers into 10 roles and believes that all 10 roles are reflected in all managers. In China, head nurses, as grassroots nursing managers in hospitals, need to address various issues, play various roles, and endure a variety of conflicts and pressures when experiencing patient safety incidents. In this environmental context, it is necessary to understand nurse managers’ personal inner experiences and real feelings when they experience adverse patient safety events.

The notice of the General Office of the National Health and Health Commission of China on the issuance of a special action plan for patient safety (2023–2025) emphasized the improvement and strengthening of adverse event management [18], whereas the General Office of the State Council of China issued the Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on the Promotion of the High-Quality Development of Public Hospitals, which explicitly pointed out the need to care for medical staff, with the head nurse acting as the manager of patient safety events, participants and victims, and their experiences and experiences directly affected the effects of adverse event management [16, 19].

Therefore, this study intends to adopt qualitative research to clarify head nurses’ understanding and inner real experience with patient safety incident management to provide further support for nurse leaders.

Participants and methods

Participants

The purpose sampling method and the maximum difference sampling strategy were used. The participants were selected from among the head nurses of the hospital in Shanxi Bethune Hospital, China. The inclusion criteria for the participants were as follows: (1) had a safety incident in the department, (2) were willing and able to fully express their true experience and feelings, and (3) provided informed consent. The exclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) head nurse in a nonclinical department of the hospital and (2) advanced head nurse. The sample size included the interview data until no new themes appeared and until the information was saturated. A total of 15 head nurses were interviewed, with 1–15 numbers instead of the interviewer.

Study methods

Data collection method

The qualitative research method was chosen to understand the experience and management perceptions of nurse leaders as second victims in patient safety incidents because their experiences, feelings, internal attitudes, and beliefs as second victims are abstract, multilayered, and not easily quantifiable, and qualitative research is ideal for examining internal experiences, attitudes, and beliefs [20]. To quickly capture the subtle experience of the nurse manager as the second victim, a semi-structured interview method centered on open-ended questions was used to collect data, and by reviewing the literature related to the feelings of the second victim in PSIs and the management cognition of the nurse manager in the last five years combined with Mintzberg’s theory of the role of the manager [14,15,16,17], the interview outline was developed for the pre-interviews. The final outline was modified according to the results of the pre-interviews. The final interview outline was modified on the basis of the results of the pre-interviews. In this study, a nurse manager who had experienced a patient safety incident and a nursing cadre responsible for analyzing and organizing data on patient safety incidents in our hospital participated in semi-structured interviews and analyses as researchers. Both researchers were involved in work related to patient safety incidents before the commencement of this study. They had published papers in this area and participated in various qualitative research workshops. The first author of this paper conducted the interviews as a researcher. The purpose of the study, confidentiality policy, and commitment to confidentiality were clearly explained to the interviewer before the interview started. General information was collected, the interviewer was made aware that the information would be kept confidential and used anonymously, and informed consent was obtained from the study participants. Code names or numbers were used instead of real names to ensure the anonymity of the data. The interviews were conducted face-to-face in a comfortable, quiet, separate room. A recording pen was used to preserve the interview data, and notes and fieldwork methods were used to supplement the interviews. The length of the interviews was determined on the basis of specific feedback from the interviewees, with the duration of the interviews for each interviewee ranging from 30 to 60 min, with an average of 45 min. Interview outline: (1) Please talk about which is the most impressive about patient safety incidents in the department? (2) How does this matter affect your work and personal life? (3) What role do you think you have played in this patient safety incident? (4) How did you respond to this incident? (5) Can you talk about your views and understanding of patient safety incidents from the perspective of nursing managers?

Data analysis

The Colaizzi 7-step analysis method was used to analyze the data. Considering the problem of language translation, we used Chinese to conduct the interviews and coding. One researcher transcribed the audio into text via Apple phone voice memo software and checked it again within 24 h after the interview. Coding was carried out independently by both researchers. The study was familiarized with the content as a whole through careful and repeated reading of the text, combined with the field notes recorded during the interviews. The text was subsequently read word by word and sentence by sentence, and the recurring expressions related to the management perceptions and negative experiences of the nurse managers were extracted to prepare for further coding. The recurring sentences were coded to construct meaning units. After thorough reflection and group discussion, the researchers reached a consensus on several subthemes and established pertinent headings to effectively coalesce these subthemes into a unified theme. All units of meaning are iterated and summarized to form theme prototypes or subthemes. Each theme prototype was defined and described by inserting the original statement. Similar theme prototypes were repeatedly compared and generalized to form themes. Finally, the generalized themes were returned to the interviewees to determine if they were clear about their true experiences and if there were deviations, to return to the first step. To ensure uniformity of coding, cross-checking was conducted at the end of independent coding to compare the coding results of the two researchers, discuss and resolve any discrepancies, and reach a consensus coding result. If the two researchers could not reach consensus, a third researcher assisted in resolving coding discrepancies and provided a neutral perspective and advice. After all the coding processes were completed, translation into English was performed with the help of software, and experts made touch-up revisions with experience in English editing.

Results

General information of the study participants

A total of 15 head nurses (3 males and 12 females) participated in this study, and the general profile of the study participants is shown in Table 1.

Key themes

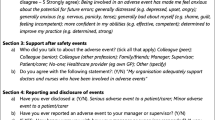

In this study, three themes and eight subthemes were obtained by analyzing the interview data of the interviewees, and finally, the emotional experience and managerial perceptions of the nurse manager as a second victim experiencing patient safety incidents were abstracted as “forced to grow up in patient safety incidents”. Table 2 shows the themes, subthemes and units.

Theme 1: emotional experience of experiencing security events

Physical and mental health-related symptoms due to passive coping and life and work disorder

This study revealed that nurse leaders who experienced patient safety events experienced varying degrees of negative emotional experiences, such as fear, guilt, depression, and self-doubt.

The negative psychological experiences of the nurse leaders in the study largely matched those of nurses who had a patient safety incident [10], differing from those of nurse second victims in that the duration of these feelings was mostly directly related to the length of the patient’s stay in the hospital and, in a few cases, could last for months or even years, in addition to the degree of harm caused by the safety incident to both the patient and the nurse second victim in relation to the ease or difficulty of managing the change. In incidents of patient safety with unexpected outcomes, the head nurse often finds themselves in a passive reaction, necessitating swift responses and immediate actions to mitigate patient harm. At the same time, they should report it to higher authorities immediately to improve the problem systematically. Therefore, the interviews revealed that many respondents experienced fatigue, decreased appetite or hyperactivity, insomnia, and inattention over time. However, these adverse experiences can cause a “domino effect”, resulting in the emergence of a fourth victim.

Participants shared their experience as follows:

“There is still normal work to be done, and it is extra time to deal with these things. Overtime is normal and very tiring”(N1).

“ When family members make a lot of noise, I am upset and do not want to eat (look ceiling)”(N2). “The occurrence is abrupt, causing an increase in heart rate”(N7).

“When such news is received, confusion ensues”(N6).

“(frown) Under normal circumstances, sleep quality is high, however, during these periods, the immense pressure may cause waking in the night, with subsequent difficulty in returning to sleep upon contemplation of the event”(N11).

“After work, mood is adversely affected, leading to absent-minded driving and navigation errors”(N8).

“(rub hands) Despite recognizing the need for emotional regulation, the return home might result in increased irritability and a propensity for disputes with family members”(N15).

Ruminating the meditation puzzle

On the basis of the frequency of keywords in this interview, such as recollection, self-examination, and replay, the majority of the nurse leaders indicated that they would engage in purposeful reflection, from which they would identify problems and deficiencies. Efforts at improvement were made from the perspective of the nursing manager. This is different from the experience of nurse second victims, which we believe is related to differences in the duties and responsibilities of nurse managers and nurse positions.

Participants shared their experience as follows:

“Sleep quality is poor and is beyond the control of this incident”(N1).

“The more I think about it, the more afraid I am, with the distressing scenes recurring upon closing my eyes”(N6).

“Upon extensive reflection, I realized that the incident was preventable and should not have occurred”(N12).

“A sense of guilt prevails owing to the unnecessary harm caused to the patient. Further analysis revealed potential flaws in my management”(N11).

“Retrospective consideration acknowledges a lack of prior emphasis, leading to feelings of despondency, if I had warned the nurses earlier, it might not have happened (the expression of regretful)”(N9).

“Later, I directly reflected that I did not pay attention to the psychological changes of patients. This is the loophole in our previous work”(N13).

Self-relief

During the interviews, it was discovered that most head nurses tend not to seek assistance when struggling to manage negative emotions, typically opting for self-resolution of these feelings. A minority of respondents indicated a willingness to engage in conversations with peers or clients who have undergone similar experiences as a means of alleviating stress. This finding is consistent with peer support in second victim support programs such as FOR YOU in the United States.

Participants shared their experience as follows:

“Assistance is generally sought for resolving issues such as pacifying patients. Personal emotional regulation is undertaken independently to avoid burdening others”(N14).

“Physical activities, such as swimming, serve as a personal method for stress relief”(N10).

“I always tell myself to adjust the mood, (clear throat) because the following work ah, cannot have more problems”(N1).

“Maybe it is because I have been working as a head nurse for a long time. Other things are too busy, so I do not think about it anymore”(N6).

“Actually, I prefer to talk to someone who has had the same experience to adjust my emotions”(N2).

Theme 2: role dilemma

Playing multiple roles with a lack of role adjustment ability

Throughout the interviews, all 15 head nurses unanimously reported the need to assume various roles during patient safety incidents, facing numerous pressures simultaneously. Some head nurses admitted that they had not fully adapted to their roles as nursing managers, experiencing varying degrees of role dissonance in managing safety events.

The participants provided the following accounts of their experiences:

“I kept explaining, comforting, and apologizing every day, but in fact, I was also very devastated”(N1).

“When there is a conflict, I am the coordinator. When I need to contact various departments, I am the Serving as both mediator during conflicts and liaison officer. After this happened, nothing went well”(N3).

“The initial steps include coordinating with the patient’s family and organizing departmental discussions for analysis, followed by devising and overseeing improvement strategies. The necessity to oscillate between roles—offering apologies with a smile to patients, then adopting a stern demeanor with nurses, I even feel like I am going to be schizophrenic”(N10).

Blurred role positioning and initial signs of job burnout

During the interviews, some head nurses expressed uncertainty regarding their specific duties and role expectations in the context of patient safety incidents, highlighting a lack of clarity on appropriate actions. Moreover, a minority acknowledged their own victimhood within these incidents.

The participants provided the following accounts of their experiences:

“No one has taught me what to do. I think I should also be a victim”(N1).

“I have no experience in this field before, so I can only grope for it. How to communicate with patients is not very clear, and it is the same for nurses”(N5).

“The burden feels singular, prompting a desire for disengagement”(N11).

“Despite not being directly responsible, the emotional toll is significant, leading to considerations of early retirement”(N15).

Theme 3: nursing management obstruction and the remodeling of the management concept

Event replay is impeded

The interviews revealed that although respondents intended to conduct debriefings after the incidents, they faced various challenges during these replays. These barriers included nurses’ emotional barriers, environmental barriers, and the hospital’s traditional punitive cultural climate and culture of shame.

Participants shared their experience as follows:

“Inquiry was halted as the nurse began to cry, rendering further questioning impossible”(N2). “Nurses’ fears resulted in disjointed communication”(N6).

“Discrepancies between the accounts of the nurse and the patient’s family were noted, yet detailed questioning was impeded by the nurse’s tears”(N10).

“The situation evolved into a conundrum, with all parties claiming ignorance in the absence of surveillance, indicating a lack of accountability”(N11).

“Despite inconsistencies between the nurse’s statements and factual events, revealing the truth proved difficult”(N15).

Inaccurate analysis of safety incidents

During the interviews, most head nurses placed significant emphasis on identifying the root cause of incidents. However, the accuracy of such analyses is often compromised by obstacles encountered during the reconstruction of safety events and variations in individual management capabilities.

The participants provided the following accounts of their experiences:

“Given the limitations of personal capabilities, concerns arise regarding the appropriateness of problem analysis and improvement measures. I hope the superior department will provide suggestions”(N10).

“The precision of root cause analysis is sometimes questionable owing to potential issues in recreating the event, compounded by a lack of verifiable evidence, potentially leading to recurring adverse events”(N4).

“Identifiable root causes may not be actionable or sufficient to prevent future incidents, rendering the analysis process seemingly futile”(N13).

Subversion and remolding of the nursing management concept

Following the incidents, most respondents recognized deficiencies in their proactive management and questioned their existing management approaches. This led to adjustments in management techniques, including increased inspection frequency and a complete overhaul of management styles.

Participants shared their experiences as follows:

“Similar procedures have previously been executed by nurses without issue. The current situation, which has taken me by surprise, may indicate flaws within my management approach”(N14).

“In response, a more stringent and detailed management approach will be adopted”(N7).

“They will be supervised more often, and special attention may be given to some key people or key time periods”(N6).

“Prior management practices were broadly conceptual, focusing mainly on the overarching framework. This incident highlights the importance of meticulous attention to detail, despite its seemingly trivial nature, underscoring its necessity”(N3).

Discussion

The study aimed to describe the experience and cognition of head nurses during patient safety incidents, find the confusion of head nurses, and try to propose possible solutions, in order to provide references for senior managers of hospitals.

Nursing administrators and hospital management are advised to pay attention to the physical and psychological changes experienced by nurse leaders after experiencing a security incident and are called upon to provide support for nurse leaders in a variety of ways

This study revealed that head nurses’ experiences of patient safety incidents are accompanied by different degrees of fear, guilt, depression, self-doubt and so on, similar to nurses’ negative psychological experiences of second victims; moreover, head nurses experience patient safety incident doubts about self-nursing management ability and self-denial, in line with the Scott second victim recovery trajectory model [21] and Lee’s reaction process model [22]. At present, the second victims are mostly nurses. In contrast, the feelings and experiences of nurse manager second victims are ignored, and the work of the nurse manager has a direct impact on the handling of patient safety incidents; therefore, we call on relevant higher authorities to pay attention to nurse manager second victims and to support nurse manager second victims from the good safety culture atmosphere and the hospital’s organizational system. Some studies [23] have shown that a nonpunitive culture in hospitals can reduce the pain of nurse second victims and help nurse leaders handle patient safety incidents rationally and calm nurse second victims; therefore, we still need to work on creating a nonpunitive patient safety culture to create a relaxing external environment for nurse leaders’ second victims. Moreover, the results of our interviews revealed that in the face of patient safety incidents, the main source of stress for nurse leaders lies in workload and time allocation, which is similar to the findings of domestic scholars [24]; therefore, we should start by reducing the workload to reduce the stress of nurse leaders. It is recommended that the Department of Nursing focus daily on the second victim work of nurse leaders, establish a professional team, and use psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool [25] to identify the population of nurse managers who need to pay attention to and establish a reserve team of nurse managerial personnel. After identifying the symptoms of nurse managers’ second victims, some of the daily management work of the nurse managers’ second victims can be transferred to the reserve managers to reduce the workload and work pressure of the nurse managers’ second victims, on the basis of which the workload and work pressure of the nurse managers’ second victims can be reduced, on the basis of Scott’s three-level support for second victims. With the CANDOR (commutation and optimal resolution tool-kit) solution toolkit constructed on the basis of the theoretical framework of Scott’s three-level support model for second victims [26], patient communication counseling services and the initiation of the incident review process can be carried out. A positive thinking-based intervention can also be used to support nurse practitioners who are second victims.

Strengthening the education and training of nurse leaders’ management ability, breaking through the role dilemma and improving job competence

Most clinical nurse leaders are nurses with excellent technical nursing skills who do not have professional management skills and need to learn on the job. BENNER [27], in the theory of competency development, noted that it takes 2—3 years for an individual to adapt to the job, and the multidimensional and constantly updating role of the nurse leader also suggests that it is not enough to improve the competency of the position only by enriching practical experience. In this interview, most head nurses said that they could not change roles at any time after experiencing the event, did not understand the specific management content and were unable to be competent in multiple roles. Moreover, they did not understand the second victim or the specific content of the second victim or respond to the patient safety incident, which coincides with the findings of Li Peitao [28]. One study [24] revealed that nurse leaders’ educational qualifications and years of service affect their nursing management ability and that the number of graduate degree holders and the number of years of service are associated with a high management level. This study suggested that we should pay attention to the continuing education of nurse leaders’ academic qualifications, that at the same time, we should pay attention to providing more attention and support to nurse leaders with less than 5 years of service, and that we should pay attention to post-management training for newly appointed nurse leaders. Zhou Guanghua [17] developed a nurse leader role behavior evaluation scale based on Mintzberg’s management theory that is based on the ten roles of managers as a framework for the construction of a nursing management practice behavioral entry pool, which nursing department managers can use to evaluate the role behavioral competence of nurse leaders. Liu Xiaoli [29] used the nurse manager job competency model as a guide to construct a hierarchical training system for nurse managers, including the communication ability, management ability and role orientation and adaptability required for nurse managers, which can be used as a reference for nursing managers to establish a scientific training system curriculum for nurse managers.

Advocating for a comprehensive security incident management system for hospital administrations

In this interview, the nurse manager’s confusion in improving the analysis of adverse events was focused mainly on the two aspects of event replay being hindered and the root cause analysis is unknown. As restoring adverse events can cause secondary victimization by bringing shame to the second victim and blocking the restoration of the event replay, the results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies [30, 31]. Some studies [30] have shown that the EAERI support strategy can reduce secondary harm to second victims by restoring the passing of the event and helping them to restore the adverse event objectively, and this strategy can be used as a reference for the nurse manager in the analysis of the adverse event to restore the adverse event effectively and objectively, i.e., to help restore the safety event by providing environmental support, companionship support, emotional support, respect support, and information support to the nurse second victim to help restore the safety event process. Currently, nursing safety event analysis models include the Swiss Cheese Model, Vincent Patient Safety Factor Model, SHEL Model, HFACS Model (The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System), STAMP Model (Systems Theoretic Accident Modeling and Processing), and HFACS Model (The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System). With respect to theoretic accident modeling and process, the System Engineering Initiative to Patient Safety (SEIPS), and causal analysis on the basis of systems theory (CAST) [32], for human factors, the analysis of organizational system factors has different focuses, and the use of these tools should be scientifically selected.

The establishment of an integrated safety incident management system is essential for the analysis and resolution of adverse events and for the support of patients and medical staff. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a professional team consisting of management professionals, decision makers from the nursing department, the hospital personnel department, the safety incident coordinator, and the second victim supporter, who are responsible for the different aspects of the safety incident and who can provide support to patients, nurses, and the nurse manager in the event of an adverse event.

Conclusion

This study was conducted to clarify the inner experience and management perceptions of nurse leaders’ second victims in response to patient safety events. The findings reveal that patient safety events not only have negative impacts and create role dilemmas for head nurses but also foster their deliberate reflection and growth. Additionally, the confusion in management practices and the needs arising during the growth process highlights the need for medical institutions to pay attention to and offer support. There is a critical need to establish a support system for second victims, enhance the patient safety management framework, and provide robust theoretical and practical foundations for addressing patient safety incidents.

Limitations

The scope of this study was limited to respondents from a Grade A hospital in Shanxi Province, China, resulting in a sample that may not fully represent broader perspectives. Therefore, future research should include medical institutions of various levels and from different regions to enhance understanding and provide a basis for more effectively standardizing the management of patient safety incidents more effectively.

Data availability

To access the data in this study, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Runciman W, Hibbert P, Thomson R, et al. Towards an international classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms. Int J Qual Health care: J Int Soc Qual Health Care. 2009;21(1):18–26.

Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ (Clinical Res ed). 2000;320(7237):726–7.

Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, et al. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider second victim after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325–30.

Huang R, Sun H, Chen G, et al. Second-victim experience and support among nurses in mainland China. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2022;30(1):260–7.

Mira JJ, Lorenzo S, Carrillo I, et al. Interventions in health organisations to reduce the impact of adverse events in second and third victims. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:341.

Liukka M, Steven A, Moreno MFV et al. Action after adverse events in Healthcare: an integrative literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13).

Sun L, Deng J, Xu J, et al. Rumination’s role in second victim nurses’ recovery from psychological trauma: a cross-sectional study in China. Front Psychol. 2022;13:860902.

Vanhaecht K, Seys D, Schouten L, et al. Duration of second victim symptoms in the aftermath of a patient safety incident and association with the level of patient harm: a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. BMJ open. 2019;9(7):e029923.

Luk LA, Lee FKI, Lam CS, et al. Healthcare Professional experiences of Clinical Incident in Hong Kong: a qualitative study. Risk Manage Healthc Policy. 2021;14:947–57.

Kalteh HO, Samaei SE, Mokarami H, et al. The role of demographic, job-related and psychological characteristics on the prevalence of repetitive patient safety incidents among Iranian nurses. Work (Reading Mass). 2023;74(4):1391–9.

Pramesona BA, Sukohar A, Taneepanichskul S, et al. A qualitative study of the reasons for low patient safety incident reporting among Indonesian nurses. Revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2023;76(4):e20220583.

Schrøder K, Bovil T, Jørgensen JS, et al. Evaluation of’the Buddy Study’, a peer support program for second victims in healthcare: a survey in two Danish hospital departments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):566.

Ji Z, Gao Y, Yang R, et al. Second victim recovery path and its support plan in hospitals. Chineses J Med Manage Sci. 2023;13(02):70–5.

Lv Y, Wang P, Li S, et al. A qualitaive study on nursing managers’ attitudes towards the second victim in adverse medical events. Chin J Nurs. 2019;54(08):1210–4.

Chen Y, Zhu X, Yang J. A qualitative study of caregivers’ internal experience of detecting adverse events in their coworkers. Jiangsu Health Syst Manage. 2022;33(03):344–7.

Han J, Sun H, Han J, et al. A qualitative study head nurses management experiences about nursing adverse events. J Nurs Adm. 2012;12(06):454–6.

Zhou G, Xu H, Yang W, et al. Development of a nurse leader role behavior evaluation scale based on Mintzberg’s management theory. Chin Gen Pract Nurs. 2022;20(18):2458–62.

Circular of the General Office of the National Health and Wellness Commission on the. Issuance of a Special Action Program for Patient Safety (2023–2025). http://www.gov,cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202310/content_6908044.htm

Adriaenssens J, Hamelink A, Bogaert PV. Predictors of occupational stress and well-being in First-Line nurse managers: a cross-sectional survey study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;73:85–92.

Sun X, Sun R, Liang X, et al. Research progress of methodology of consensual qualitative research and its application in nursing. J Nurs Sci. 2024;39(07):118–21.

Scott SD, McCoig MM. Care at the point of impact: insights into the second-victim experience. J Healthc risk Management: J Am Soc Healthc Risk Manage. 2016;35(4):6–13.

Lee W, Pyo J, Jang SG, et al. Experiences and responses of second victims of patient safety incidents in Korea: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):100.

Chen G, Sun H, Huang R, et al. The effects of hospital patient safety culture on distress of nurses as second victims. Chin J Nurs. 2019;54(12):1835–40.

Fan S, Zhang P, Sun J. The status ofstress and post-competency andits influencing factors in head nurses. Tianjin J Nurs. 2023;31(04):379–83.

Zhang X, Chen J, Lee SY. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of second victim experience and Support Tool. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(8):e1691–6.

Morales CL, Brown MM. Creating a care for the Caregiver Program in a ten-Hospital Health System. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2019;31(4):461–73.

Li P, Luo Y, Xu R, et al. Establishment and evaluation of the 1 + 1 + 1 training system for newly appointed head nurses. Chin Nurs Manage. 2020;20(11):1722–6.

Tilden VP, Tilden S, From novice to expert, excellence and power in clinical nursing practice - Benner, P. Res Nurs Health. 1985;8(1):95–7.

Liu X, Wu X, Li S, et al. Construction of stratified training system for head nurse based on post competency. J Nurs. 2021;28(02):10–5.

Zhang X, Li Z, Du R, et al. Construction of support strategies for nurses as the second victim in patient safety incidents. Chin Nurs Manage. 2023;23(06):893–8.

Van Gerven E, Deweer D, Scott SD, et al. Personal, situational and organizational aspects that influence the impact of patient safety incidents: a qualitative study. Revista De Calidad Asistencial: organo de la Sociedad Esp De Calidad Asistencial. 2016;31(Suppl 2):34–46.

Lu X, Wang Y, Guo X, et al. Research progress on the cause analysis models of nursing adverse events. J Nurs Sci. 2019;34(21):107–10.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no financially supporting body for this articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceptualized the study and developed the interview guides. Cuiling Zhang conducted the data collection and designed interview outline. Ziyan Yang and Yali Liang conducted the data analysis and interpretation, as well as drafted and revised the manuscript. Cuiling Zhang, Yong Feng, and Xiaohong Zhang provided critical revisions for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shanxi Bethune Hospital of China (YXLL-2023–244) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed in accordance with the recommended guidelines and regulations. The purpose and significance of the study were explained to the participants, and only those who agreed to participate were interviewed after obtaining written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Yang, Z., Liang, Y. et al. A qualitative study of head nurses’ experience in China: forced growth during patient safety incidents. BMC Nurs 23, 592 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02255-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02255-7