Abstract

Background

The adoption of Electronic Medical Records (EMR) by the healthcare sector can improve patient care and safety, facilitate structured research, and effectively plan, monitor, and assess disease. EMR adoptions in low-income countries like Ethiopia were delayed and failing more frequently, despite their critical necessity. The most popular way to solve the issue is to evaluate user preparedness prior to the adoption of EMR. However, little is known regarding the EMR readiness of healthcare professionals in this study setting. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the readiness and factors associated with health professional readiness toward EMR in Gamo Zone, Ethiopia.

Methods

An institution-based cross-sectional survey was conducted by using a pretested self-administered questionnaire on 416 study participants at public hospital hospitals in southern Ethiopia. STAT version 14 software was used to conduct the analysis after the data was entered using Epi-data version 3.2. A binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with readiness. Finally, the results were interpreted using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 400 participants enrolled in the study, with a response rate of 97.1%. A total of 65.25% (n = 261) [95% CI: 0.60, 0.69] participants had overall readiness, 68.75% (n = 275) [95% CI: 0.64, 0.73] had engagement readiness, and (69.75%) (n = 279) [95% CI: 0.65, 0.74] had core EMR readiness. Computer skills (AOR: 3.06; 95% CI: 1.49–6.29), EMR training (AOR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.06–3.67), good EMR knowledge (AOR: 2.021; 95% CI: 1.19–3.39), and favorable attitude (AOR: 3.00; 95% CI: 1.76–4.97) were factors significantly associated with EMR readiness.

Conclusion

Although it was deemed insufficient, more than half of the respondents indicated a satisfactory level of overall readiness for the adoption of EMR. Moreover, having computer skills, having EMR training, good EMR knowledge, and favorable EMR attitude were all significantly and positively related to EMR readiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

E-health is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the cost-effective application of information and communication technologies (ICT) to assist health and health-related disciplines [1, 2]. The primary issues facing healthcare systems can be greatly addressed by EMR. The delivery of healthcare services to patients is supported by the use of an electronic medical record (EMR), which is a computerized medical record used to collect, store, and share data among healthcare professionals in an organization.

Although EMRs are a vital tool for the health sector, their implementation, uptake, and utilization are still low in developing nations. Many healthcare facilities throughout the world have deployed EMR systems to enhance the process of capturing patient data, but only a select fraction of them have proven successful [3, 4]. EMRs are computerized medical information systems that gather, store, and display patient data. While maintaining the patient’s privacy and security, it may include a variety of data such as socio-demographics, insurance, past and present medication information, allergies, laboratory and test results, histories of immunizations and medical procedures, hospitalizations, progress evaluations, and others [5,6,7].

E-Health Readiness is the term used to describe how ready healthcare organizations or communities are for the anticipated change brought about by ICT-related activities. E-readiness is the capacity of an organization to foster and support the development of ICTs, including infrastructure, pertinent systems, and technical competencies [8]. EMR enhances patient care by establishing connections among all caregivers, lowering the demand for file space and supplies, and eliminating the need for staff to physically access any records [9]. However, in many developing countries the EMR system is not widely scattered or implemented [10,11,12,13].

Failure to implement EMRs has a negative impact on patients’ and healthcare professionals’ ability to access medical history, treatment information, and past diagnoses, which slows down the workflow of healthcare organizations [14]. The development of a national electronic health record is now underway in Ethiopia, while other EMR pilot programmes have been implemented in our country [15, 16]. Previous finding revealed that the proportion of EMR readiness varied across Ethiopia, with 36.5% [17] in the Sidama region, 52.8% [18] in the southwest Ethiopia, and 54.1% [2] in the northern Ethiopia.

Prior research suggested that readiness was related to age, gender, profession, level of education, and work experience [15, 19,20,21,22]. Moreover, having knowledge, computer skills, prior EMR experience, and a personal computer are associated to professional readiness [13, 23,24,25,26,27]. Previous research revealed that readiness for the adoption of EMR can be influenced by health professionals working in organizations with IT infrastructure and access to computers [15, 28]. Our literature search revealed that more studies have focused on organizational readiness than on the health professionals’ readiness [29], and no research has been done in the setting of our study.

Before implementing such systems in Ethiopia, the researchers of this study felt that it was important to assess the user’s readiness and the essential metrics. In environments with limited resources, this study also made it possible for policymakers to comprehend user needs prior to system deployment. Therefore, the objective this study was to assess readiness of health professionals towards electronic medical record system and its associated factors in public hospitals in Gamo zone, Ethiopia.

Method

Study design, setting, and period

From September to October 2022, a cross-sectional institution-based survey was undertaken among healthcare professionals working at public health institutions in the Gamo zone. Gamo zone shares a border with Wolayta and Gofa zones in the north, Lake Abaya to the northeast, Amaro and Dirashe special woredas to the southeast, and South Omo to the southwest. The administrative center of the Gamo zone is Arba Minch town. Arba Minch settlement lays 505 km (km) southwest of Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, and 275 km (km) southwest of Hawassa, the regional headquarters of southern Ethiopia. It hosted seven hospitals (one general and six primary hospitals), 56 health centers, and 299 health posts, which serve the community by providing preventive and curative services [30].

Study population, sample size and sampling procedure

All healthcare workers who were employed full-time in the Gamo zones of southern Ethiopia were eligible for this study. Health professionals working in Gamo zone hospitals (Arba Minch, Geress, Selamber, Chencha, and Kemba) were study population. The sample size was calculated using data from a study carried out in Ethiopia, which showed that 52.8% of medical professionals had EHR readiness levels comparable to those used in the current study [18]. We also take into account the following assumptions: a non-response rate of 10%, a margin of error of 5%, and a confidence level of 95%. Finally, the study’s sample size was 416 health professionals. We were proportionally allocated the total sample size, 416, to those five public hospitals found in the zones. Then, in those five hospitals, random selections of healthcare professionals were executed (Fig. 1).

Data collection technique and data quality assurance

A pretested self-administered questionnaire was used to collect the data. The questionnaire had questions about socio-demographics, behavior, technology, and organizations. The survey was written in English because the study’s participants are well-educated and capable of understanding it. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was also used to test reliability (the overall Cronbach alpha for healthcare professionals readiness was 0.87, knowledge was 0.81 and attitude was 0.89). For two days, the investigators trained the supervisors and data collectors on the purpose of the study, data gathering techniques, data collection tools, respondents’ approach, data confidentiality, and respondent’s rights. Five health information technicians with strong communication skills were used for data collection, and two master’s-educated health professionals served as supervisors. The supervisors checked the questionnaire’s accuracy every day. Before the analysis, data cleaning and cross-checking were also performed. Following any necessary questionnaire adjustments, the actual data collection process began.

Operational definition

Core readiness

Core readiness was assessed in this study using a series of four questions, with participants scoring 50% or higher being assumed to have core readiness and participants scoring less than 50% being believed to not have core readiness [18].

Engagement readiness

Engagement readiness is the active willingness and participation of individuals in the deployment of the electronic medical record (EMR). In this study, participants’ levels of engagement readiness was assessed by a series of four questions. Participants with scores of 50% or more were considered to be engaged, while those with scores averaging less than 50% were considered not to be so [31].

Overall readiness

Health professionals were classified as having an overall readiness if they met both the core and engagement readiness criteria [24].

Knowledge

Eight questions were used to examine if a person possesses the fundamental understanding of EMR, and knowledge is measured as a variable. Professionals with knowledge scores of 50% or higher were considered to have good knowledge [23].

Attitude

Attitude was measured as a latent variable of a set of fifteen questions that assesses the individual perception of EMR measured on a five point Likert scale. A score of mean or above was used to classify as having a favorable attitude [32].

Data processing and analysis

Data from the survey were entered using Epi-data version 3.1, coded by using alpha-numeric symbols, and analyzed using STATA version 14 software. To describe demographic characteristics, attitudes, and readiness for EMR, descriptive analyses were conducted. Moreover, the binary logistic regression method was used to identify the independent factors related to readiness. The variance inflation factor was used to test for multicollinearity (VIF). Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were used to assess the model’s goodness of fit at P-value > 0.05. In multi-variable logistic regression analysis, odds ratio was used to examine the strength of association between factor and outcome variables and 95% CI and P-value < 0.05 were computed to assess statistical significance.

Result

Socio demographic characteristics of study participant

Of the total 416 participants, 400 returned the questionnaire with a response rate of 97.1%.In this study, majority of the participants (53.3%) were within the age category 20–30 and 62% of the participants were male professionals. About 131 (28.25%) respondents were nurses, 72(18%) were doctors, 66(16.50%) were public health, 51(12.75%) were midwives and 69(17.25%) were other heath professional. Of the respondents, 322 (80.50%) have a bachelor degree while 36(9%) health professionals had a Master’s degree and above. About 184 (46%) of the study participants had more than five years of professional experience, while 29 (7.25%) had less than two years. Moreover, 288(72%) have worked at the hospital where they are currently employed (Table 1).

Organizational and technical factors

Majority (65%) of respondents have a personal computer at home and 337 (84.25%) of the participants had computer related skills. Only 109 (27.25%) of the study’s participants had prior EMR training, and only 616 (41%) had prior EMR system experience. More than half of (52%) the health professionals had access to a computer in their workplace; of these, 63.37% participant used for data recording, 20.30% for report writing, 10.89% for reading, and 5.45% for other purposes like video accessing. Moreover, more than half of the respondents reported that their hospitals have an IT technician and have a functioning IT department (Table 2).

Knowledge and attitude of health professionals for EMR

In this study the majority of respondents 259 (64.75%) had good knowledge of EMR. Likewise, 229 (57.25%) respondents had a favorable opinion of the EMR system (Fig. 2).

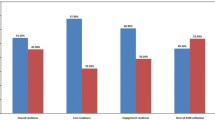

Readiness of health professional to EMR

Out of all participants, 65.25% [95% CI: 0.60, 0.69] had overall readiness for EMR, while 68.75% [95% CI: 0.64, 0.73] had engagement readiness for EMR and 69.75% [95% CI: 0.65, 0.74] had core readiness (Fig. 3).

Factors associated with health professional readiness to EMR

In this study, four factors were shown to be significantly associated with EMR readiness in the multivariable logistic regression model: computer skills, EMR training, EMR knowledge, and EMR attitude.

Health care professionals with computer skills were 3 times (AOR: 3.06; 95% CI: 1.49–6.29) more likely to be ready to use an EMR system than their counterparts. Health professionals who had taken EMR training were about 2 times (AOR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.06–3.67) more likely ready to use EMR system than those who had not. Health professionals with good EMR knowledge had 2times (AOR: 2.021; 95% CI: 1.19–3.39) higher odds of being ready than those with poor knowledge. Moreover, it was revealed that professionals with a favorable attitude had 3 times (AOR: 3.00; 95% CI: 1.76–4.97) more likely ready than those with unfavorable attitude (Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the EMR readiness of healthcare professionals and related variables in Southern Ethiopia. Despite the fact that there are several levels of EMR readiness, the authors of this study emphasized on healthcare providers’ levels of readiness. In this study, the overall readiness of health professionals for an EMR system was 65.25%.This finding was similar with study done in Ethiopia (62.3%) [23]. This finding was higher than study conducted in Southwest Ethiopia (52.8%) [18], Sidama region (36.5%) [32], Ghana (54.9%) [24], Myanmar (54.2%) [33]. The discrepancy may be attributable to the development and extension of Technological infrastructure, as well as the Ethiopian government’s priority placement of the digitization of the health information system in its ambition to modernize the health sector [34, 35]. The regular interaction of health workers with the global digital world may also be a factor. Moreover, the method used to categorize professional readiness, variations in sample size, or variations in socio-demographic factors could all contribute to this disparity [36].

In a multivariable logistic regression model, it was revealed that computer skills, EMR training, EMR knowledge, and EMR attitude were all significantly and positively related to EMR readiness. In this study, Health care professionals with computer skills were more likely to be ready to use an EMR system than their counterparts. This finding is supported by previous report in Ethiopia [2, 18, 37], Greek [38], Saudi Arabia [39]. This could be due to the fact that, if used for everyday healthcare management, people with computer capabilities won’t have as much trouble using the EMR system. Additionally, the availability of computers and computer skills may have had a direct impact on health professionals’ perceptions on the usage of computer-based systems. Regarding health professionals who had taken EMR training were about more likely ready for an EMR system as compared to those health professionals who had not taken any EMR training before. This finding was in line with previous studies in Ethiopia [23, 40]. The findings indicating that education and training typically alter people’s perspectives and thoughts may help to explain this.

In this study, health professionals with good knowledge were more likely to be ready for an EMR system than those with poor knowledge. This result was consistent with findings from various studies in Greek [38], Lebanon [41], Australia [42]. This may be explained by the fact that professionals who recognize the benefits of electronic medical record systems could be more encouraged to employ them as a result of their awareness. Because of their tendency to do so, they may also be more prepared to accept technology advantages and be ready to adopt EMR systems.

Moreover, health professionals who had favorable attitude about electronic medical record systems were more likely ready to EMR system than unfavorable attitude towards the system. This may be explained by the fact that experts may be more motivated to use the system if they have a favorable opinion of it and show a keen interest in it. According to earlier research, health professionals’ attitudes influence both their readiness and how well they use the system in Ethiopia [23], Saudi Arabia [39], USA [43]. Furthermore, this could be due to the fact that healthcare providers have a positive opinion of those technologies, which motivates them to be more enthusiastic and dedicated towards using EMR [18, 44].

Strength and limitation

The strength of this study was the first in its field to analyze the precise measurements that must be made to raise healthcare providers’ readiness levels prior to the deployment of EMR. In low-income nation settings, it also highlighted several key measurements that must be made before ERM implementation. The study was cross-sectional, thus causality cannot be concluded. The study’s primary shortcoming was the lack of triangulation with qualitative results. Additionally, it didn’t include other forms of ready, such as organizational and technological readiness, because there isn’t a tool that can compress all forms of ERM health preparedness.

Conclusion

Although it was deemed insufficient, more than half of the respondents indicated an acceptable level of overall readiness for the adoption of EMR. According to this study, having computer skills, having EMR training, good EMR knowledge, and favorable EMR attitude were all significantly and positively related to EMR readiness.

Prior to implementation, health personnel should receive training to raise their level of EMR understanding. Capacity building and awareness creation activities should also be made in this regard. Given that it would improve professional abilities and make them feel more competent and ready to use the system, it stands to reason that this could also alter health professionals’ attitudes.

Implications of the study

Future deployments of digital health systems could be affected by this study. Increasing computer accessibility, providing an EMR training course, and promoting a positive attitude towards EMR are potential strategies to boost the success rate of EMR implementations in Ethiopia. The electronic medical record will be implemented and customized in the study environment using the findings of the study as a foundation. The main goal was to increase the success of EMR implementation by determining the readiness of healthcare professionals.

Data Availability

Full data set and materials pertaining to this study can be obtained from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- EHR:

-

Electronic Health Record

- EMR:

-

Electronic Medical Record

- ICT:

-

Information Communication Technology

- IT:

-

Information Technology

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

References

Qureshi Q, Ahmad I, Nawaz A. Readiness for e-health in the developing countries like Pakistan. Gomal J Med Sci. 2012;10(1):160–3.

Biruk S, Yilma T, Andualem M, Tilahun B. Health Professionals’ readiness to implement electronic medical record system at three hospitals in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak [Internet]. 2014;14(1):115. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-014-0115-5.

World Health Organization. Atlas of eHealth country profiles. The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage. WHO, Geneva [Internet]. 2016;392. Available from: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Atlas+of+eHealth+Country+Profiles#0.

Tubaishat A. Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of electronic health records among nurses: Application of Technology Acceptance Model. Informatics Heal Soc Care [Internet]. 2018 Oct 2;43(4):379–89. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/17538157.2017.1363761.

Ariffin NAbt, Ismail N, bt A, Kadir IKA, Kamal JIA. Implementation of Electronic Medical Records in developing countries: Challenges & Barriers. Int J Acad Res Progress Educ Dev. 2018;7(3):187–99.

Janett RS, Yeracaris PP. Electronic medical records in the american health system: Challenges and lessons learned. Cienc e Saude Coletiva. 2020;25(4):1293–304.

Lakbala P, Dindarloo K. Physicians’ perception and attitude toward electronic medical record. Springerplus. 2014;3(1):1–8.

Dugar D. https://www.selecthub.com/medical-software/how-to-conduct-ehr-readiness-assessment/.

Gesulga JM, Berjame A, Moquiala KS, Galido A. Barriers to Electronic Health Record System Implementation and Information Systems Resources: A Structured Review. Procedia Comput Sci [Internet]. 2017;124:544–51. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.12.188.

Albagmi S. The effectiveness of EMR implementation regarding reducing documentation errors and waiting time for patients in outpatient clinics: a systematic review. F1000Research. 2021;10:514.

Noraziani K, Nurul’Ain A, Azhim MZ, Ekhab S, Drak B, Sharifa Ezat WP, et al. An overview of electronic medical record implementation in healthcare system: lesson to learn. World Appl Sci J. 2013;25(2):323–32.

Graves T. A manual for developing countries. Community Eye Health. 2002;15(44):64–4.

Berihun B, Atnafu DD, Sitotaw G. Willingness to Use Electronic Medical Record (EMR) System in Healthcare Facilities of Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia. 2020;2020.

Ahmed MH, Bogale AD, Tilahun B, Kalayou MH. Intention to use electronic medical record and its predictors among health care providers at referral hospitals, north-West Ethiopia, 2019 : using unified theory of acceptance and use technology 2 (UTAUT2) model. 2020;1–11.

Yehualashet G, Andualem M, Tilahun B. The attitude towards and use of Electronic Medical Record System by Health Professionals at a Referral Hospital in Northern Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. J Heal Inf Afr. 2015;3(1):19–29.

Taye G, Ayele W, Biruk E, Tassew B. The Ethiopian Health Information System: where are we? And where are we going? Ethiop J Heal Dev. 2021;35(1):1–4.

Abore KW, Debiso AT, Birhanu BE, Bua BZ, Negeri KG. Health professionals’ readiness to implement electronic medical recording system and associated factors in public general hospitals of Sidama region, Ethiopia. PLoS One [Internet]. 2022;17(10 October):1–12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276371.

Ngusie HS, Kassie SY, Chereka AA, Enyew EB. Healthcare providers ’ readiness for electronic health record adoption: a cross – sectional study during pre – implementation phase. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;1–12.

Muthee V, Bochner AF, Kang’a S, Owiso G, Akhwale W, Wanyee S et al. Site readiness assessment preceding the implementation of a HIV care and treatment electronic medical record system in Kenya. Int J Med Inform [Internet]. 2018;109(February 2017):23–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.10.019.

Gesulga JM, Berjame A, Moquiala KS, Galido A. Barriers to Electronic Health Record System Implementation and Information Systems Resources: A Structured Review. Procedia Comput Sci [Internet]. 2017;124:544–51. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877050917329563.

Faris AAzmiSAl, Saleh KA, Al Ojayan OA. https://vlibrary.emro.who.int/imemr/physicians-perceptions-about-the-newly-implemented-electronic-medical-records-systems-at-the-primary-health-care-centers-in-kuwait-2/.

Dimitrovski T, Bath PA, Ketikidis P, Lazuras L. Factors affecting general practitioners’ readiness to accept and use an electronic health record system in the republic of north macedonia: a national survey of general practitioners. JMIR Med Informatics. 2021;9(4).

Awol SM, Birhanu AY, Mekonnen ZA, Gashu KD, Shiferaw AM, Endehabtu BF, et al. Health professionals’ readiness and its associated factors to implement electronic medical record system in four selected primary hospitals in Ethiopia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:147–54.

Abdulai AF, Adam F. Health providers’ readiness for electronic health records adoption: A cross-sectional study of two hospitals in northern Ghana. PLoS One [Internet]. 2020;15(6):1–11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231569.

Ghazisaeedi M, Mohammadzadeh N, Safdari R, Sharifian R, Rahimi A. Evaluation of Hospital Information System (HIS) in General Hospitals: user perspectives PhD, faculty member of Health Information Management Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran PhD student of. Health Inform Manage Tehran Univ of. 2013;10:660–3.

Ghazisaeidi M, Ahmadi M, Sadoughi F, Safdari R. A Roadmap to pre-implementation of electronic health record: the key step to success. Acta Inf Med. 2014;22(2):133–8.

Cucciniello M, Lapsley I, Nasi G, Pagliari C. Understanding key factors affecting electronic medical record implementation: a sociotechnical approach. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2015;15(1):268. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0928-7.

Ghazisaeidi M, Ahmadi M, Sadoughi F, Safdari R. An assessment of readiness for pre-implementation of electronic health record in Iran: a practical approach to implementation in general and teaching hospitals. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52(7):532–44.

Yilma TM, Tilahun B, Mamuye A, Kerie H, Nurhussien F, Zemen E et al. Organizational and health professional readiness for the implementation of electronic medical record system: an implication for the current EMR implementation in northwest Ethiopia. 2023;1–7.

Sector H. Ethiopia Emergency type: multiple events reporting period : 1–29 February 2020 • Ethiopia ’ s Minister of Health declared a confirmed COVID-19 outbreak on 13 March 2020. Since then a total of 11 cases with 261 contacts have been • A yellow fever outbrea. 2020;(February).

Id JKK, Keizer N, De, Id RC. Assessment of organizational readiness to implement an electronic health record system in a low-resource settings cancer hospital: A. 2020;1–17.

Weldeab K, Id A, Tamiso A, Id D, Birhanu BE. Health professionals ’ readiness to implement electronic medical recording system and associated factors in public general hospitals of Sidama region. Ethiopia. 2022;201:1–12.

Min H, Id O, Minn Y, Id H, Win TT, Han ZM et al. Information and communication technology literacy, knowledge and readiness for electronic medical record system adoption among health professionals in a tertiary hospital, Myanmar : a cross-sectional study. 2021;1–15.

Tegegne MD, Wubante SM. Identifying barriers to the adoption of Information Communication Technology in Ethiopian Healthcare Systems. A systematic review. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2022;13:821–8.

Mondejar ME, Avtar R, Diaz HLB, Dubey RK, Esteban J, Gómez-Morales A et al. Digitalization to achieve sustainable development goals: Steps towards a Smart Green Planet. Sci Total Environ [Internet]. 2021;794:148539. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969721036111.

Nölke L, Mensing M, Krämer A, Hornberg C. Sociodemographic and health- (care-) related characteristics of online health information seekers: a cross-sectional german study. 2015;1–12.

Walle AD, Shibabaw AA, Tilahun kefyalew N, Atinafu WT, Adem JB, Demsash AW et al. Readiness to use electronic medical record systems and its associated factors among health care professionals in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Informatics Med Unlocked [Internet]. 2023;36:101140. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352914822002775.

Melas CD, Zampetakis LA, Dimopoulou A, Moustakis VS. An empirical investigation of Technology readiness among medical staff based in greek hospitals. Eur J Inf Syst. 2014 Nov;23(6):672–90.

Aldebasi B, Alhassan AI, Al-nasser S, Abolfotouh MA. Level of awareness of saudi medical students of the internet-based health- related information seeking and developing to support health services. 2020;8:1–8.

Kalayou MH, Endehabtu BF, Guadie HA, Abebaw Z, Dessie K, Awol SM et al. Physicians ’ Attitude towards Electronic Medical Record Systems: An Input for Future Implementers. 2021;2021.

Saleh S, Khodor R, Alameddine M, Baroud M. Readiness of healthcare providers for eHealth: the case from primary healthcare centers in Lebanon. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Nov;16(1):644.

Yusif S, Hafeez-Baig A, Soar J. e-Health readiness assessment factors and measuring tools: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2017;107(June):56–64.

Mason P, Monestime JP. Overcoming barriers to Implementing Electronic Health Records in Rural Primary. Care Clin. 2017;22(11):2955.

Ghazisaeidi M, Ahmadi M, Sadoughi F. An Assessment of Readiness for Pre-Implementation of Electronic Health Record in Iran: a Practical Approach to Implementation in general and Teaching Hospitals. 2013.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the Arba Minch University College of health science ethical review board for the approval of ethical clearance and each hospital for giving a supporting letter. The authors would like to extend their heartfelt thanks to healthcare professional, data collectors, and supervisors who participated in this study.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Proposal preparation, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data was done by SH, TD, YH, and SA instruct the study design data cleaning and analysis. SH drafted the manuscript and all authors have a substantial contribution in revising and finalizing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval (approval number IRB/1163/2020) was obtained from Arba Minch University, College of medicine and health science institution review board. A formal letter from the university addressed to the participating hospitals was taken and submitted. Informed written consent was obtained from the participants after thoroughly discussing the idea behind the study, and study participant rights. Participants were also assured that the confidentiality of the information they provided would be maintained. All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hailegebreal, S., Dileba, T., Haile, Y. et al. Health professionals’ readiness to implement electronic medical record system in Gamo zone public hospitals, southern Ethiopia: an institution based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 773 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09745-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09745-5