Abstract

Background

Supervised consumption sites (SCS) and overdose prevention sites (OPS) have been increasingly implemented in response to the ongoing overdose epidemic in Canada. Although there has been a dramatic increase in overdose deaths since the start of the SARS-CoV 2 (COVID-19) pandemic, little is known about how SCS access may have been affected by this pandemic. Therefore, we sought to characterize potential changes in access to SCS during the COVID-19 pandemic among people who use drugs (PWUD) in Vancouver, Canada.

Methods

Between June and December 2020, data were collected through the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) and the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS), two cohort studies involving people who use drugs. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine individual, social and structural factors associated with self-reported reduced frequency of SCS/OPS use since COVID-19.

Results

Among 428 participants, 223 (54.7%) self-identified as male. Among all individuals surveyed, 63 (14.8%) reported a decreased frequency of use of SCS/OPS since COVID-19. However, 281 (66%) reported that they “did not want to” access SCS in the last 6 months. In multivariable analyses, younger age, self-reported fentanyl contamination of drugs used and reduced ease of access to SCS/OPS since COVID-19 were positively associated with a decreased frequency of use of SCS/OPS since COVID-19 (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Approximately 15% of PWUD who accessed SCS/OPS reported reduced use of these programs during the COVID-19 pandemic, including those at heightened risk of overdose due to fentanyl exposure. Given the ongoing overdose epidemic, efforts must be made to remove barriers to SCS access throughout public health crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

North America remains in the midst of an escalating overdose epidemic driven largely by the proliferation of synthetic opioids in the illicit drug supply. Unfortunately, since the start of the SARS-CoV 2 (COVID-19) pandemic, overdose-related deaths have increased dramatically. In Canada, opioid toxicity deaths increased from 3747 (April 2019 – March 2020) to 7362 (April 2020 – March 2021), an increase of nearly 96% [10, 15].

Prior to the pandemic supervised consumption sites (SCS) were one of the many strategies being employed in Canada to address the overdose crisis [9, 26]. SCS, also known as safe injection sites or overdose prevention sites (OPS), are places where people who use drugs (PWUD) can go to safely consume pre-obtained substances under supervision [3]. SCS staff also offer life-saving support in the event of overdose and referrals to external services [17]. As of January 2020, more than 70 SCS were operating in Canada, the overwhelming majority of which opened after 2017. Of these, 9 SCS were operating in Vancouver [16].

SCS have been shown to provide a number of health benefits among PWUD [11], including reduced risk of overdose mortality. For example, a previous study found that after the opening of the first SCS in Vancouver, overdose-related deaths decreased by 35% in city blocks within 500 m of the SCS [13]. Another comprehensive review of evidence derived from SCS evaluations noted that there had been no overdose deaths in any SCS to date as SCS are well equipped to handle overdose incidents [18].

With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, SCS in many settings in Canada and elsewhere experienced disruptions in service delivery, including closures, difficulty communicating with clients about service changes, and restrictions on capacity [4]. In British Columbia, monthly SCS visits dropped from nearly 60, 000 per month to approximately 23, 000 per month [1]. A qualitative study done in Canada found that 53% of PWUD who also used harm reduction services in their sample population felt that there were negative changes in service delivery. They further go on to report that public health measures implemented in response to COVID-19 further negatively impacted PWUD. Some of these impacts include increased substance use, sharing/re-use of substance supplies, unattended overdose events, and food and housing insecurity [20].

However, we know of few studies that have examined potential changes in SCS utilization patterns among PWUD after the emergence of the pandemic, including decreased frequency of use of these services. We therefore sought to characterize decreased frequency of SCS use after the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic as a public health emergency among PWUD participating in two prospective cohort studies in Vancouver, Canada. Understanding these changes will allow us to further inform efforts to ensure functional access to harm reduction services throughout public health crises.

Methods

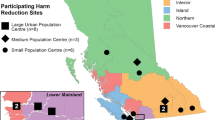

Data for this study were drawn from two open prospective cohort studies of PWUD in Vancouver, Canada: the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) and the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS). Both cohorts have been described in detail in previous literature [24, 27]. However, to briefly summarize, these cohorts have been recruiting participants through community-based methods, including street outreach, self-referral, and word of mouth since May of 1996. VIDUS includes adults (18 years and older) who are HIV-negative and have injected unregulated drugs within the month prior to their enrolment. ACCESS participants are HIV-positive adults who used any unregulated substance (other than or in addition to cannabis) within the month prior to their enrolment. Participants in the VIDUS cohort who HIV seroconvert after their enrolment are transferred to the ACCESS cohort. All participants provided written informed consent at enrolment and ethics has been approved by Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board. Both cohorts use harmonized study protocols to facilitate pooled analyses.

At baseline and at 6-month intervals afterwards, participants complete interviewer- and nurse-led questionnaires and provide blood samples for serology, as well as urine for drug screening. The questionnaire covers a variety of topics including demographics, substance use, healthcare access, and socio-structural exposures. To compensate participants for their involvement, participants receive a $40 CAD stipend for every study visit.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all in-person data collection was suspended between March 2020 and July 2020. After July 2020, infection control measures were put in place to resume data collection. Participant interviews were completed over telephone or videoconferencing. Study-owned cell phones and private spaces were loaned to those who required them. They were then able to pick up their cash honoraria in person or have it e-transferred if they had access to a bank account.

Between March and July of 2020, study questionnaires were modified to include questions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. One of these questions was used to assess the primary outcome of this study, which read as follows: “Has the frequency of your use of these sites [i.e., SCS/OPS] changed since the beginning of the public health emergency?”. The outcome was dichotomized using the following responses: “I use them less” vs. “I use them more” or “My use stayed the same”. Potential correlates were identified based on past studies that assessed SCS access among PWUD [8, 25], and included: age (per year older), self-identified gender (man vs. woman/other), ethnicity/ancestry (white vs. Black, Indigenous, and people of colour), education (high school or greater vs. other), employment (yes vs. no), residence in Downtown Eastside neighbourhood in Vancouver (yes vs. no), daily non-medical prescription opioid use (yes vs. no), daily cocaine use (yes vs. no), daily crystal methamphetamine use (yes vs. no), daily non-injection crack-cocaine use (yes vs. no), benzodiazepine use (yes vs. no), suspected that a drug used contained fentanyl (yes vs. no), used drugs alone (yes vs. no), engagement in opioid agonist therapy (yes vs. no), non-fatal overdose (yes vs. no), witnessed an overdose (yes vs. no), experience physical violence (yes vs. no), syringe/ drug use equipment sharing (yes vs. no), inability to access treatment (yes vs. no), unstable housing (yes vs. no), sex work (yes vs. no), incarceration (yes vs. no), jacked up (this refers to being stopped, searched, or detained) by the police (yes vs. no), cohort/ HIV status (ACCESS vs. VIDUS), ever tested positive for COVID-19 (yes vs. no), concern about COVID-19 on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 indicating greatest concern (1–5 vs. 6–10), any chronic health conditions (yes vs. no), and ease of accessing SCS/OPS changed since COVID-19 (same vs. easier vs. harder). All drug use and behavioral variables refer to the 6 months prior to questionnaire date unless otherwise indicated.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to assess the associations between the correlates of interest and reduced frequency of SCS/OPS use since COVID-19. Correlates of interest with a univariable p-value < 0.10 were included in a backward elimination procedure, with the least significant variable removed at each step until the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was achieved. All p-values were two-sided and all statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Results

In total, there were 428 people who use drugs included in this analysis, of which 223 (54.7%) were male. The median age was 51 years old (1st to 3rd quartile = 42–58). Among all individuals surveyed, 63 (14.8%) reported a decreased frequency of use of SCS/OPS since COVID-19. However, when asked about accessing SCS, 281 of all individuals reported that they “did not want to” in the last 6 months. In univariable logistic regression analyses (Table 1), factors positively associated with a decreased frequency of SCS/OPS use since COVID-19 include younger age (Odds ratio [OR] = 0.95, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.92–0.98), suspected fentanyl exposure (OR = 4.09, 95% CI: 1.81–9.24), witnessing an overdose (OR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.01–3.14), unstable housing (OR = 2.04, 95% CI: 1.15–3.36), and decreased ease of access to SCS/OPS since COVID-19 (OR = 6.77, 95% CI: 3.66–12.53).

In a multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2), factors that remained positively associated with difficulty accessing SCS/OPS included younger age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.92–0.98), suspected fentanyl exposure (AOR = 2.61, 95% CI: 1.10–6.19) and decreased ease of access to SCS/OPS since COVID-19 (AOR = 5.11, 95% CI: 2.92–10.41).

Discussion

We found that approximately 15% of a community-recruited sample of PWUD in Vancouver reduced their frequency of SCS use after the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. In multivariable analyses (Table 2), reduced use of SCS was associated with suspected fentanyl contamination of drugs used and perceived decreased ease of access to SCS/OPS since the onset of restrictions associated with COVID-19.

Our finding that reduced use of SCS occurred among 15% of all PWUD in this study and was associated with perceived decreased ease of SCS accessibility are aligned with other research indicating that the accessibility of many services was compromised during the COVID-19 pandemic [6, 22]. Harm reduction services were no exception [23]. Worldwide, the uncertainty regarding COVID-19 restrictions, as well as challenges associated with efforts to reduce COVID-19 spread while still preventing overdoses, may have contributed to adverse impacts on the accessibility of overdose prevention services, including SCS [7, 19]. Although not explored in this study, factors known to constrain other health programs during the COVID-19 pandemic that may have affected SCS delivery, include concerns among staff about safety, staff shortages, lack of proper access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), unforeseen illness, and the rapidly changing global situation [5, 12, 21], which in turn may have prompted changes in the way SCS operate.

While it is evident that COVID-19 public health policies impact the delivery of harm reduction services, our study reveals that these changes had a substantial impact on the access patterns of PWUD in Vancouver. In total, 15% of all PWUD interviewed in our sample reported a decreased frequency of use of SCS/OPS since COVID-19. This is in line with a recent Canadian study which showed that 53% of their participants who used harm reduction services identified negative changes in service delivery [20].

We found that suspected exposure to illicit fentanyl was positively correlated with a reduced frequency of SCS use. Recent data released from the BC Coroner’s service indicates that the proportion of overdose deaths attributable to exposure to high concentrations of fentanyl has increased [2]. This finding stands in contrast to a study conducted in Baltimore prior to the pandemic, which found that “thinking drugs contained fentanyl” was independently associated with willingness to use SCS [14]. Further research should be undertaken to further explore the association observed herein. However, given that SCS are uniquely well-positioned to respond to fentanyl-related overdose, it is concerning that COVID restrictions have created additional obstacles for accessing SCS among those with suspected fentanyl exposure. Accordingly, efforts should be made to minimize barriers to SCS access and increase the availability of services specifically for those at risk of fentanyl exposure.

Our study sheds light on the associations between COVID-19 and access to SCS, and serves to identify subpopulations of PWUD who may be vulnerable to disruptions in service access, including younger individuals and those who report reduced ease of service access. Our findings further suggest that it is possible that reduced SCS access may be a contributing factor to the rise in overdose in recent years. Our study also has limitations. One limitation is that we examined the impacts of COVID-19 on service access at a particular time early in the epidemic, and mitigation strategies have likely evolved since this time. Still, our findings point to the need to continue to find creative ways to improve service access, even when epidemics such as COVID-19 are occurring. Another limitation is that the cohort studies included in this analysis are not randomly recruited and therefore may not be representative of PWUD in Vancouver or elsewhere. Further, we relied on self-report, which may be vulnerable to socially desirable responding and recall bias. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot infer causation, and unmeasured confounding may be present.

Conclusion

In summary, a small but significant proportion of participants in our study reported reduced use of SCS in Vancouver during the COVID-19 pandemic, with younger participants, as well as those who reported suspected fentanyl exposure and reduced ease of SCS access being more likely to report reduced use of SCS. Given the ongoing overdose epidemic, it is therefore critical that efforts are made to ensure accessible harm reduction services, including during concordant public health crises.

Availability of data and materials

The data used for this study are not publicly available and can be requested from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board.

Abbreviations

- SCS:

-

Safe Consumption Site

- OPS:

-

Overdose Prevention Site

- PWUD:

-

People Who Use Drugs

- COVID-19:

-

SARS-CoV 2

- VIDUS :

-

Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study

- ACCESS:

-

AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services

- BC:

-

British Columbia

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

References

BC Centre for Disease Control. Overdose response indicator report: March 2022. Vancouver: Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions; 2020. Retrieved from http://www.bccdc.ca/resourcegallery/Documents/Statistics%20and%20Research/Statistics%20and%20Reports/Overdose/Overdose%20Response%20Indicator%20Report.pdf

BC Coroners Service. Illicit drug toxicity deaths in BC; 2022. p. 1–26. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/life-events/death/coroners-service/statistical-reports

Belackova V, Salmon A. Overview of international literature - supervised injecting facilities & drug consumption rooms - Issue 1. - drugs and alcohol. 2022. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/34158/.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on substance use treatment capacity in Canada. 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.ccsa.ca/impacts-covid-19-pandemic-substance-use-treatment-capacity-canada.

Collins A, Ndoye C, Arene-Morley D, Marshall B. Addressing co-occurring public health emergencies: the importance of naloxone distribution in the era of COVID-19. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102872.

Cousins S. COVID-19 has “devastating” effect on women and girls. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):301–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31679-2.

Dunlop A, Lokuge B, Masters D, Sequeira M, Saul P, Dunlop G, et al. Challenges in maintaining treatment services for people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-00370-7.

Kennedy M, Klassen D, Dong H, Milloy M, Hayashi K, Kerr T. Supervised injection facility utilization patterns: a prospective cohort study in Vancouver, Canada. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(3):330–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.024.

Kerr T, Mitra S, Kennedy M, McNeil R. Supervised injection facilities in Canada: past, present, and future. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0154-1.

Khatri U, Perrone J. Opioid use disorder and COVID-19: crashing of the crises. J Addict Med. 2020;14(4):e6–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000684.

Levengood T, Yoon G, Davoust M, Ogden S, Marshall B, Cahill S, et al. Supervised injection facilities as harm reduction: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5):738–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.017.

Livingston E, Desai A, Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1912. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5317.

Marshall B, Milloy M, Wood E, Montaner J, Kerr T. Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1429–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62353-7.

Park J, Sherman S, Rouhani S, Morales K, McKenzie M, Allen S, et al. Willingness to use safe consumption spaces among opioid users at high risk of fentanyl overdose in Baltimore, Providence, and Boston. J Urban Health. 2019;96(3):353–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00365-1.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Interactive map: Canada’s response to the opioid overdose crisis. 2022a. https://health.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/opioids/responding-canada-opioid-crisis/map.html.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. 2022b. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants.

Patterson T, Bharmal A, Padhi S, Buchner C, Gibson E, Lee V. Opening Canada’s first Health Canada-approved supervised consumption sites. Can J Public Health. 2018;109(4):581–4. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-018-0107-9.

Potier C, Laprévote V, Dubois-Arber F, Cottencin O, Rolland B. Supervised injection services: what has been demonstrated? A systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:48–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.012.

Roxburgh A, Jauncey M, Day C, Bartlett M, Cogger S, Dietze P, et al. Adapting harm reduction services during COVID-19: lessons from the supervised injecting facilities in Australia. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00471-x.

Russell C, Ali F, Nafeh F, Rehm J, LeBlanc S, Elton-Marshall T. Identifying the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on service access for people who use drugs (PWUD): a national qualitative study. J Subst Abus Treat. 2021;129:108374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108374.

Sárosi P. Harm reduction responses to COVID-19 in Europe: regularly updated Infopage – Drugreporter. 2022. https://drogriporter.hu/en/how-harm-reducers-cope-with-the-corona-pandemic-in-europe/.

Smith K, Bhui K, Cipriani A. COVID-19, mental health and ethnic minorities. Evid Based Ment Health. 2020;23(3):89–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2020-300174.

Stowe M, Calvey T, Scheibein F, Arya S, Saad N, Shirasaka T, et al. Access to healthcare and harm reduction services during the COVID-19 pandemic for people who use drugs. J Addict Med. 2020;14(6):e287–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000753.

Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PGA, Yip B, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JSG, et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA. 1998;280:547–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.6.547.

Ti L, Buxton J, Harrison S, Dobrer S, Montaner J, Wood E, et al. Willingness to access an in-hospital supervised injection facility among hospitalized people who use illicit drugs. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):301–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2344.

Urban Health Research Initiative. Drug situation in Vancouver. Vancouver; 2013. p. 5–10. https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/dsiv2013.pdf

Wood E, Kerr T. What do you do when you hit rock bottom? Responding to drugs in the city of Vancouver. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17:55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.12.007.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken on the unceded traditional homeland of the Coast Salish Peoples, including the xʷmə θkwə yə m (Musqueam), Sḵ wxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Sə lílwə taɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. We would also like to acknowledge Cristy Zonneveld and Steve Kane for their support in leading the cohort studies involved in this project.

Funding

The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U01DA038886 and R01DA021525) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (AWD-017542 CIHR 2020). KH holds the St. Paul’s Hospital Chair in Substance Use Research and is supported in part by the NIH (U01DA038886), a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Scholar Award, and the St. Paul’s Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KH, MJM, and TK designed and managed the cohort studies that the present study built upon. TK and EG designed the present study. ZC conducted the statistical analyses. EG drafted the manuscript, prepared the figures, and incorporated suggestions from all co-authors. All authors made significant contributions to the conceptions of the analyses, interpretations of the data, and writing and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent at enrolment and ethics has been approved by Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MJM’s institution has received an unstructured gift from NG Biomed, Ltd., to support his research. MJM is the Canopy Growth professor of cannabis science at the University of British Columbia, a position created by unstructured gifts to the university from Canopy Growth, a licensed producer of cannabis, and the Government of British Columbia’s Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions. The funder that supports MJM did not have any role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gubskaya, E., Kennedy, M.C., Hayashi, K. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to supervised consumption programs. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 18, 16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00521-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00521-6