Abstract

Objective

To investigate the distribution and influence of comminution in femoral neck fracture (FNF) patients after cannulated screw fixation (CSF).

Methods

From January 2019 to June 2020, a total of 473 patients aged 23–65 years with FNF treated by CSF were included in the present study. Based on location of the cortical comminution, FNF patients were assigned to two groups: the comminution group (anterior comminution, posterior comminution, superior comminution, inferior comminution, multiple comminutions) or the without comminution group. The incidence of postoperative complications, quality of life and functional outcomes was recorded at 1-year follow-up.

Results

Comminution was more likely to appear in displaced FNF patients (86.8%) compared with non-displaced FNF patients (8.9%), and the rate of comminution was closely associated with Pauwels classification (3.2% vs 53.5% vs 83.9%, P < 0.05). The incidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH, 11.3% vs 2.9%, P < 0.05), nonunion (7.5% vs 1.7%, P < 0.05), femoral neck shortening (21.6% vs 13.4%, P < 0.05) and internal fixation failure (11.8% vs 2.9%, P < 0.05) was significantly higher in FNF patients with comminutions, especially with multiple comminutions, than those without. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the Harris hip score (HHS, 85.6 ± 15.6 vs 91.3 ± 10.8, P < 0.05) and EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D, 0.85 ± 0.17 vs 0.91 ± 0.18, P < 0.05) between FNF patients with comminution and those without. There was no significant difference in Visual analogue scale scores (VAS, 1.46 ± 2.49 vs 1.13 ± 1.80, P > 0.05) between two groups at 1 year post-surgery.

Conclusion

Comminution is a risk factor for postoperative complications in young- and middle-aged patients with displaced and Pauwels type III FNF who undergo CSF. This can influence the recovery of hip function, thereby impacting quality of life. Further evaluation with a more comprehensive study design, larger sample and long-term follow-up is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Femoral neck fractures (FNFs) are a common injury in both elderly patients as a result of low-energy trauma and younger patients as a result of high-energy trauma. FNFs are considered a serious injury due to the high-risk nature of surgical treatment, particularly in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities who are at higher risk of poor outcomes [1,2,3]. It has been estimated that the total number of hip fractures will increase to 6.3 million worldwide by 2050, with FNFs accounting for approximately 50% of the total number [4, 5]. The neck of the femur has a complex blood supply and unique biomechanical characteristics, which can result in a series of complications such as nonunion and osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), a leading cause of pain and dysfunction [6]. These poor outcomes result in high disability rates and health-care resource use, creating a serious socioeconomic burden [5].

Therapeutic strategies for FNFs include either arthroplasty or internal fixation depending on a number of factors, including patient age, fracture pattern and functional requirements. In contrast to the management FNF in elderly patients, multiple cannulated screw fixation (CSF) is a widely accepted approach for the management of FNF in younger patients based on its easy operation, reduced tissue damage and preservation of original joints [7, 8]. The rate of complications including nonunion, ONFH and implant failure of internal fixation following FNFs is 9–30%, resulting in disability and subsequently requiring revision surgery or conversion to arthroplasty procedures at rates of 20–36% [9,10,11]. Evidence suggests that high failure rate of internal fixation for FNFs is related to inadequate reduction, fracture type, bone quality and loosening of fixation [10,11,12].

An increasing number of studies indicate that disruption to the cortex of the femoral neck is common in patients with FNFs. For example, Collinge et al. found that 96% of patients with vertical shear FNF had comminutions in the inferior (94%) and posterior (82%) femoral neck [13]; Huang et al. found that 36.5% of displaced FNF patients had a disrupted posterior cortex, acting as an independent risk factor for postoperative ONFH, union and shortening [6]. Several investigations also show that comminution of the femoral neck is a serious risk factor for loss of cortical support of cannulated screws, resulting in internal fixation failure even when adequate reduction is achieved [7, 12]. Therefore, the integrity of the cortex of femoral neck is believed to be an important factor for successful surgical management of patients of all ages with FNF.

However, the distribution and influence of comminutions in the femoral neck in FNF patients with CSF remains largely unknown. The goals of present study are to discuss the characteristics of cortical defect in the femoral neck of FNF patients and determine whether there is a correlation between comminution distribution and prognosis. A more robust understanding of these findings will improve understanding of the FNF injury mechanism of FNF and may improve treatment strategies and reduce postoperative complications.

Materials and methods

Participants

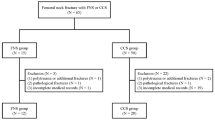

This retrospective cohort study included patients with FNFs in Tianjin Hospital from January 2019 to June 2020. All methods were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Hospital. All participants were fully aware of the nature, purpose, procedures and risks of the study and provided written informed consent. The flowchart of participants is shown in Fig. 1.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria include: (1) age ranging from 18 to 65 years old; (2) with a unilateral FNF; (3) underwent multiple CSF and achieved acceptable reduction quality; (4) completed 1-year follow-up; and (5) consent to be included in the study.

Exclusion criteria include: (1) pathological fracture or old fracture (more than 14 days); (2) previous ipsilateral hip diseases; (3) bilateral FNF or combined with femoral shaft fracture; (4) a bone metabolism disorder; (5) the occurrence of diseases affecting the function of lower limbs, death or no follow-up; (6) serious nervous system or cognitive impairment such as dementia or Parkinson disease; (7) pregnant or lactating women; and (8) incomplete clinical data.

Radiographic assessment and grouping

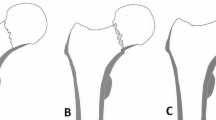

Anteroposterior (AP) radiographs were employed to estimate fractures based on the Garden classification [14] and Pauwels classification [15]. Postoperative three-dimensional computed tomography (3D-CT) reconstruction was performed to evaluate the existence and location of comminution in the femoral neck (Fig. 2). All imaging was separately reviewed, and morphology was assessed by two radiologists and two orthopedic trauma surgeons. All disagreements were resolved by discussion. Patients were divided into 6 groups according to the location of comminution in the femoral neck: (1) anterior comminution; (2) posterior comminution; (3) superior comminution; (4) inferior comminution; (5) multiple comminutions; and (6) without comminution.

Operative and postoperative procedures

Closed reduction or open reduction with three standard CSFs of FNFs was carried out in all patients under either general or epidural anesthesia. The reduction quality (excellent, good and fair) of the FNFs was considered to be acceptable according to that described by Haidukewych et al. [16]. Patients were encouraged to rehabilitate in bed immediately after surgery with non-weight-bearing mobilization over 8 weeks, weight bearing was allowed with walker/crutches once callus formation was verified using radiography, and full weight bearing was allowed depending on fracture healing at monthly postoperative re-examination.

Follow-up and outcome measurement

After discharge, patients were required to go to the special follow-up clinic once a month until the fracture was healed. After the fracture healed, patients were rechecked at 1 year post-op, which included radiographic and clinical examinations and surveyed for information on complications, quality of life, pain and hip function. If the participant could not attend the clinic for re-examination, they were asked to undergo X-ray imaging at local hospital and e-mail images to the surgeons. Finally, primary and secondary outcomes were measured at 1 year post-op.

Primary outcomes were postoperative complications including nonunion, ONFH, shortening and fixation failure. Fracture nonunion was defined as a clear, visible fracture line or the absence of bridging cortical bone at 6 months postoperative, which was evaluated by imaging examination [17, 18]. ONFH was identified using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or radiography, following the radiological criteria by Arlet et al. [19]. According to the description by Zlowodzki et al. [20], the length of femoral neck was measured and femoral neck shortening was defined as a shortening length exceeding 5 mm in immediate postoperative film compared with last follow-up [20]. Internal fixation failure was evaluated by radiography, including screw withdraw, implant cut out, screw loose, varus deformity > 10° and re-displacement > 5 mm.

Secondary outcomes were the Harris hip score (HHS), EQ-5D (EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire) score and visual analogue scale score (VAS) at 1 year post-op. HHS was widely used to evaluate hip function, including four aspects: pain (1item, 0–44 points), function (7 items, 0–47 points), deformity (1 item, 0–4 points) and range of activity (2 items, 0–5 points) [21]. EQ-5D, developed by the EuroQol team, is a patient reporting tool to measure quality of life [22]. The questionnaire contains five questions covering five different aspects including mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, and a specific value set for Chinese patients obtained by Luo et al. [23]. VAS (score from 0 to 10) evaluates pain intensity on a scale where 0 is painless; less than 3 is mild pain that the patient can endure; 4–6 is pain that the patient can bear and can sleep; and 7–10 is severe pain that the patient cannot bear [24].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The categorical variables of clinical data and outcomes were assessed using Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. The continuous variable data were assessed for a fit to a normal distribution and for homogeneity of variance using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Bartlett test, which was represented as mean ± SD. Student’s t test or the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for inter-group comparisons. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 473 patients with FNFs were identified from January 2019 to June 2020, 82 patients were lost to follow-up, 6 patients declined participation, and 1 patient dropped out due to re-fracture. A total of 384 patients completed the 1-year follow-up and were included in this study. Of those patients, 14 had anterior comminution, 88 had posterior comminution, 16 had superior comminution, 60 had inferior comminution, 34 had multiple comminutions, and 172 patients did not have comminution (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in regard to age, sex, body mass index (BMI), injury mechanism, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, from initial injury to operation, operative time, duration of hospitalization and follow-up time among the groups (P > 0.05, Table 1). However, intraoperative blood loss and open reduction rate were increased in the multiple comminution group compared with other groups (P < 0.05, Table 1).

To analyze the morphological characteristics of the cortical defect in the femoral neck, we surveyed the relationship between fracture type and comminution distribution. As shown in Table 2, for Garden classification, the proportion of comminution in displaced FNFs was significantly higher than that in non-displaced FNFs (P < 0.05). The comminution was concentrated on the posterior and inferior of the femoral neck in both non-displaced and displaced FNFs (P < 0.05), while there was no difference in comminution distribution between the two types of fractures (P > 0.05). The amount of comminution increased significantly with an increase in each Pauwels classification type (P < 0.05). The incidence of posterior and inferior comminution was higher than the other groups, and there was no difference in comminution distribution in different fracture patterns (P > 0.05).

As illustrated in Table 3, the occurrence of postoperative complications, including nonunion, ONFH, shortening and fixation failure, was significantly higher in the comminution group than those without comminution (P < 0.05). As demonstrated by further inter-group analysis, the incidence of postoperative complications in FNF with multiple comminutions was significantly higher than those in the other four groups (P < 0.05). There was no clear correlation between a single comminution in the femoral neck and postoperative complications (P > 0.05).

The HHS, EQ-5D index and VAS score were measured in patients at 1 year postoperative. As displayed in Table 4, there was a significant difference in the HHS and EQ-5D index between the FNF with comminution group and the FNF without comminution group (P < 0.05). However, there was no difference in VAS scores between the FNF with comminution group and FNF without comminution group (P > 0.05). There was no close relationship between secondary outcomes and FNF patients with different comminution locations 1 year after surgery (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The incidence of FNF in young- and middle-aged people is growing as a result of high-energy traumas, resulting in impacts to quality of life, hip function and labor capacity, thereby creating an economic burden to the global society [25, 26]. Despite advances in head-preserving surgical techniques and implants for FNF, the high rates of postoperative osteonecrosis, nonunion and femur shortening are problematic and challenging for young and active adults [27, 28]. It is commonly believed that satisfactory reduction, accurate positioning and placement of the implant and appropriate rehabilitation are the critical to achieve fracture healing and recovery of function, in addition to preventing varus collapse and ONFH [10,11,12]. Cortical bone deficiency in the femoral neck is considered an important factor for biological healing and biomechanical stability for FNF with internal fixation [7, 29]. Evidence has shown that 50–96% of FNF patients have femoral neck comminution, most of which is posterior comminution with the incidence between 50 and 82% [6, 13, 30,31,32]. This may be explained because young- and middle-aged people with FNF are usually subjected to high-energy trauma, which exceeds the stress that the femoral neck can bear, resulting in the comminuting of the bone. In the elderly population, the cortex of femoral neck is thicker and often more frail, resulting in easier comminution in the femoral neck as a result of low-energy trauma. FNFs with comminution are more unstable [36]; therefore, we aim to explore the relationship between morphological characteristics of femoral neck deficiencies and prognosis to improve the therapeutic strategies for future patients with similar injuries.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic study to describe the distribution of cortical comminution in patients with FNF. Similar to previous studies, our results showed that cortical comminution existed in displaced FNFs compared with non-displaced FNFs, while posterior comminution was the most common type of cortical deficiency in the femoral neck. The comminution mechanism of the posterior cortex in FNFs had been described in different ways. Garden et al. [33] believed that extreme external rotation of the distal fragment would impact the fragile posterior cortical shell near the junction with the head fragment, leading to posterior comminution and fracture, resulting in an intracapsular fracture. Kocher et al. [34] indicated that in the course of the injury, at the moment of vertical trauma in the femoral neck simultaneous with external rotation of the limb, the femoral head is restricted by the iliofemoral ligament and capsule and impinged by acetabulum’s posterior ring, leading to posterior cortical comminution. Additionally, several studies suggest regional cortical comminution is related to the characteristics of cortical bone structure in the femoral neck. For example, because the cortex of femoral neck is thinner from the anterior inferior to the posterior, the greatest cortical damage would be in the posterior side when the femoral neck is subjected to trauma and impact [35, 36]. Unexpectedly, our results found that inferior comminution was the second most common in FNF patients, which has not been reported before. We suggest the following injury mechanism of FNF with inferior comminution: When the proximal femur suffers both vertical traumas with varus, stress concentration would be in the inferior femoral neck, subsequently causing cortical comminution; the inferior cortex in the femoral neck is thinner where the cortical damage occurs in this weak area when the femoral neck subjected to trauma and impact.

Furthermore, our study explored the relationship between Pauwels classification type and distribution of cortical comminutions in FNF patients. Surprisingly, the incidence rate of cortical comminution increased positively with fracture types. Therefore, our findings suggest that in vertical FNFs, not only higher-degree lesions but also cortical deficiency worsens instability, progressive fracture displacement and risk of varus collapse, resulting in serious postoperative complications and fixation failure.

ONFH is a common and serious complication after internal fixation of FNFs, especially in young patients [37]. Incidence in this population is as high as 8.9% [38]. A great deal of evidence indicates that the occurrence of ONFH is the result of interruption of the femoral head blood supply due to traumatic vascular injury or insufficient blood supply caused by the increase of intracapsular pressure after fracture. Another potential cause of ONFH is stress on the femoral head caused by instability of the normal structure of the proximal femur, resulting excessive physiological load and mechanical destruction of trabeculae bone, leading to collapse [39,40,41]. Increasing evidence shows that that cortical comminution is a factor in ONFH in FNF patients after surgery. For example, Scheck et al. found posterior comminution increased the risk of postoperative ONFH in FNF patients [29]; Huang et al. found that ONFH after internal fixation in FNF patients with posterior cortical comminution was 34.2%, which was much higher than that in patients without comminution (4.8%) [6]. Similar to previous studies, our findings show that the incidence of ONFH in FNF patients with comminution was significantly higher than those without comminution. In particular, FNF patients with multiple comminutions had a much higher risk of ONFH compared to those with a single comminution. There was no significant correlation between the location of the comminution and rate of ONFH. There is a paucity of research investigating the influence of cortical deficiency on FNFs after internal fixation. We propose the following mechanism caused by cortical comminution in the femoral neck: The destruction of the cortex in the femoral neck in FNF patients, particularly the posterior cortex, can severely disrupt the blood supply to the femoral head, regardless of whether the reduction was restored or not, leading to ONFH. Previous reports have found that initial displacement and posterior comminution are closely associated with femoral neck blood vessel damage; at the same time, increased fracture lines and comminutions can lead to devastating damage in the lateral epiphyseal artery and posterior retinacular vessels, a risk factor in femoral head collapse [42, 43]; and some studies have found that cortical defects are a factor in mechanical instability after internal fixation of FNFs [44], which can impact the distribution of surface stress in the femoral head, particularly in weight-bearing areas, contributing to trabecular microfracture and collapse. Additionally, in clinical practice, it is difficult to reset FNF with comminutions by close reduction, and therefore, open reduction is regarded as necessary to achieve a quality or anatomic reduction [45]. However, anterior and anterolateral approaches during open reduction can lead to lateral femoral circumflex artery injury, retinacular vessels traversing disruption and the periosteum and capsular reflections [46], which can increase the risk of ONFH. Blood vessel damage, instability and increased open reduction rate in FNF patient with multiple comminutions were the main reasons for postoperative ONFH.

The prognosis of femoral neck fractures can be affected by several serious conditions, one of the most common being nonunion [47]. The rate nonunion is between 10 and 30%, a complication which can result in functional disability and require revision surgery [27, 38, 48]. An increasing number of studies have identified that cortical deficiency is a critical factor in nonunion in FNFs. For example, Huang et al. found that posterior comminution in FNFs reduced axial load resistance, resulting in early fracture re-displacement and nonunion [6]; Rawall et al. highlighted that young patients with significant posterior comminution were found to have higher nonunion rates [49]. Similarly, our results show that nonunion rates in FNF patients with comminution were significantly higher than that of FNF patients without comminution (7.5% vs 1.7%), while nonunion rate of FNF patients with multiple comminutions (14.7%) was significantly higher in comparison with FNF patients with a single comminution. Posteromedial comminution of the femoral neck is considered an important factor in fracture stability [29]. According to biomechanical findings, the decline in contact stability between internal fixation and the cortex can happen in FNFs with comminution, leading to rotation of the fragments and initial displacement, resulting in nonunion and osteosynthetic failure [50, 51]. Our results found that the number of internal fixation failures in FNF patients with comminution was more than that in FNF without comminution. Similarly, FNF patients with multiple comminutions had the highest incidence of internal fixation failure (23.5%). Previous studies [13, 50, 52] investigating whether or not anatomical reduction was achieved show that comminutions can create difficulty reconstituting a bony buttress and potentially return to the position of injury, causing internal fixation failure. Additionally, the comminutions can produce a mechanical environment where implants can lose fixed-angle properties, resulting in the fracture site bearing more axial and torsion load creating an ineffective buttress against varus re-displacement.

Increasingly strong evidence suggests that femoral neck shortening occurs as much as 32–65.7% in FNF patients after internal fixation, contributing to gait disorder, hip dysfunction and decline in quality of life [53, 54]. Huang et al. found that the incidence of femoral neck shortening in FNF patients with comminution was significantly higher than that in patients without comminution [6]. In accordance with conclusion of Zlowodzki et al.[20], our study found that the incidence of femoral neck shortening was 18.0% in all cases, and the incidence neck shortening in FNF patients with a disrupted cortex was much higher (21.6%) than that in FNF patients without a disrupted cortex (13.4%). We suggest that cortical deficiency in the femoral neck can impact stability in fracture sites after reduction, causing fragments to slide along the implant allowing impact at the fracture site, particularly when patients experience axial loading during early weight bearing.

The functional outcomes and health-related quality of life indicators in FNF patients with comminution have not been well studied. In our study, we found that HSS and EQ-5D index were significantly worse in patients with comminutions than those without comminution, whereas there were no differences in VAS scores between the two groups. FNF patients with multiple comminutions had worse HSS, EQ-5D index and VAS scores in comparison with those with a single comminution. In our view, higher incidence of ONFH, nonunion and femoral neck shortening in FNF patients with multiple comminutions can have a significant influence on operative recovery of hip function, leading to poor function scores.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, short follow-up duration, monocentric analysis with a local population and small sample size. A relatively high proportion of patients did not complete the follow-up (89 out of 473 patients, 18.8%), with the main reasons being change of contact information, incomplete imaging and refusal to participate, which may have influenced our data collection. Finally, although we authenticated fracture morphology using 3D-CT scan, there was no clear definition or description for characteristics of cortical comminution in the femoral neck, resulting in inaccurate grouping of fractures and potential for bias. Larger, multicenter and longer duration randomized studies may help to address these limitations.

Conclusion

In present study, we found that comminution in the femoral neck commonly occurred in displaced FNFs compared to non-displaced FNFs, with posterior comminution and inferior comminution the most common patterns. As hypothesized, comminution in the femoral neck, especially multiple comminutions, was a risk factor for postoperative ONFH, nonunion, femoral neck shortening and internal fixation failure in young- and middle-aged patients, consequently influencing recovery of hip function and quality of life. We hope that these findings highlight the importance of appropriate FNF management in order to avoid unnecessarily postoperative complications and promote functional recovery in patients.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- FNF1:

-

Femoral neck fracture

- CSF:

-

Patients after cannulated screw fixation

- HHS:

-

Harris hip score

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- ONFH:

-

Osteonecrosis of femoral head

- AP:

-

Anteroposterior

- 3D-CT:

-

Three-dimensional computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging;

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ASA:

-

American society of anesthesiologists

References

Augat P, Bliven E, Hackl S. Biomechanics of femoral neck fractures and implications for fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(Suppl 1):S27–32.

Zuckerman JD. Hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1519–25.

Basilico M, Vitiello R, Oliva MS, Covino M, Greco T, Cianni L, et al. Predictable risk factors for infections in proximal femur fractures. Adv Musculoskelet Dis Infect: SOTIMI 2019. 2020;34:77–81.

Raaymakers EL. Fractures of the femoral neck: a review and personal statement. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2006;73:45–59.

Florschutz AV, Langford JR, Haidukewych GJ, Koval KJ. Femoral neck fractures: current management. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:121–9.

Huang TW, Hsu WH, Peng KT, Lee CY. Effect of integrity of the posterior cortex in displaced femoral neck fractures on outcome after surgical fixation in young adults. Injury. 2011;42:217–22.

Wang SH, Yang JJ, Shen HC, Lin LC, Lee MS, Pan RY. Using a modified Pauwels method to predict the outcome of femoral neck fracture in relatively young patients. Injury. 2015;46:1969–74.

Ye Y, Hao J, Mauffrey C, Hammerberg EM, Stahel PF, Hak DJ. Optimizing stability in femoral neck fracture fixation. Orthopedics. 2015;38:625–30.

Stockton DJ, Lefaivre KA, Deakin DE, Osterhoff G, Yamada A, Broekhuyse HM, et al. Incidence, magnitude, and predictors of shortening in young femoral neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:e293–8.

Do LND, Kruke TM, Foss OA, Basso T. Reoperations and mortality in 383 patients operated with parallel screws for Garden I-II femoral neck fractures with up to ten years follow-up. Injury. 2016;47:2739–42.

Slobogean GP, Stockton DJ, Zeng BF, Wang D, Ma B, Pollak AN. Femoral neck shortening in adult patients under the age of 55 years is associated with worse functional outcomes: analysis of the prospective multi-center study of hip fracture outcomes in China (SHOC). Injury. 2017;48:1837–42.

Johannesdottir F, Turmezei T, Poole KE. Cortical bone assessed with clinical computed tomography at the proximal femur. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:771–83.

Collinge CA, Mir H, Reddix R. Fracture morphology of high shear angle “vertical” femoral neck fractures in young adult patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:270–5.

Garden RS. Malreduction and avascular necrosis in subcapital fractures of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53:183–97.

Shen M, Wang C, Chen H, Rui YF, Zhao S. An update on the Pauwels classification. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016;11:161.

Haidukewych GJ, Rothwell WS, Jacofsky DJ, Torchia ME, Berry DJ. Operative treatment of femoral neck fractures in patients between the ages of fifteen and fifty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1711–6.

Butt MF, Dhar SA, Gani NU, Farooq M, Mir MR, Halwai MA, et al. Delayed fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures in younger adults. Injury. 2008;39:238–43.

Chen CY, Chiu FY, Chen CM, Huang CK, Chen WM, Chen TH. Surgical treatment of basicervical fractures of femur–a prospective evaluation of 269 patients. J Trauma. 2008;64:427–9.

Ficat P, Arlet J. Pre-radiologic stage of femur head osteonecrosis: diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1973;59(Suppl 1):26–38.

Zlowodzki M, Ayeni O, Petrisor BA, Bhandari M. Femoral neck shortening after fracture fixation with multiple cancellous screws: incidence and effect on function. J Trauma. 2008;64:163–9.

Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–55.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72.

Luo N, Liu G, Li M, Guan H, Jin X, Rand-Hendriksen K. Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for China. Value Health. 2017;20:662–9.

Lee KA, Kieckhefer GM. Measuring human responses using visual analogue scales. West J Nurs Res. 1989;11:128–32.

Miyamoto RG, Kaplan KM, Levine BR, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD. Surgical management of hip fractures: an evidence-based review of the literature. I: femoral neck fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:596–607.

Davidovitch RI, Jordan CJ, Egol KA, Vrahas MS. Challenges in the treatment of femoral neck fractures in the nonelderly adult. J Trauma. 2010;68:236–42.

Slobogean GP, Sprague SA, Scott T, Bhandari M. Complications following young femoral neck fractures. Injury. 2015;46:484–91.

Liporace F, Gaines R, Collinge C, Haidukewych GJ. Results of internal fixation of Pauwels type-3 vertical femoral neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1654–9.

Scheck M. The significance of posterior comminution in femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;152:138–42.

Scheck M. Intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck. Comminution of the posterior neck cortex as a cause of unstable fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1959;41-A:1187–200.

Brown JT, Abrami G. Transcervical femoral fracture. A review of 195 patients treated by sliding nail-plate fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:648–63.

Meyers MH, Harvey JP Jr, Moore TM. The muscle pedicle bone graft in the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck: indications, operative technique, and results. Orthop Clin North Am. 1974;5:779–92.

Garden RS. Reduction and fixation of sub capital fractures of the femur. Orthop Clin NorthAm. 1974;5(4):83.

Tian S, Chen Y, Yin Y, Zhang R, Hou Z, Zhang Y. Morphological characteristics of posterior wall fragments associated with acetabular both-column fracture. Sci Rep. 2019;9:20164.

Bell KL, Loveridge N, Power J, Garrahan N, Stanton M, Lunt M, et al. Structure of the femoral neck in hip fracture: cortical bone loss in the inferoanterior to superoposterior axis. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:111–9.

Crabtree N, Loveridge N, Parker M, Rushton N, Power J, Bell KL, et al. Intracapsular hip fracture and the region-specific loss of cortical bone: analysis by peripheral quantitative computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1318–28.

Xu JL, Liang ZR, Xiong BL, Zou QZ, Lin TY, Yang P, et al. Risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of femoral head after internal fixation of femoral neck fracture:a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:632.

Damany DS, Parker MJ, Chojnowski A. Complications after intracapsular hip fractures in young adults. A meta-analysis of 18 published studies involving 564 fractures. Injury. 2005;36:131–41.

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7:407–13.

Ueo T, Tsutsumi S, Yamamuro T, Okumura H, Shimizu A, Nakamura T. Biomechanical aspects of the development of aseptic necrosis of the femoral head. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1985;104:145–9.

Nishii T, Sugano N, Ohzono K, Sakai T, Haraguchi K, Yoshikawa H. Progression and cessation of collapse in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;400:149–57.

Zlotorowicz M, Szczodry M, Czubak J, Ciszek B. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery with respect to the vascularity of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:1471–4.

Ehlinger M, Moser T, Adam P, Bierry G, Gangi A, de Mathelin M, et al. Early prediction of femoral head avascular necrosis following neck fracture. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97:79–88.

Kauffman JI, Simon JA, Kummer FJ, Pearlman CJ, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. Internal fixation of femoral neck fractures with posterior comminution: a biomechanical study. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13:155–9.

Keshet D, Bernstein M. Open reduction internal fixation of femoral neck fracture-anterior approach. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34(Suppl 2):S27–8.

Lazaro LE, Klinger CE, Sculco PK, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. The terminal branches of the medial femoral circumflex artery: the arterial supply of the femoral head. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:1204–13.

Mathews V, Cabanela ME. Femoral neck nonunion treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;419:57–64.

Li L, Zhao X, Yang X, Tang X, Liu M. Dynamic hip screws versus cannulated screws for femoral neck fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15:352.

Rawall S, Bali K, Upendra B, Garg B, Yadav CS, Jayaswal A. Displaced femoral neck fractures in the young: significance of posterior comminution and raised intracapsular pressure. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:73–9.

Rupprecht M, Grossterlinden L, Sellenschloh K, Hoffmann M, Puschel K, Morlock M, et al. Internal fixation of femoral neck fractures with posterior comminution: a biomechanical comparison of DHS(R) and Intertan nail(R). Int Orthop. 2011;35:1695–701.

Wright DJ, Bui CN, Ihn HE, McGarry MH, Lee TQ, Scolaro JA. Posterior inferior comminution significantly influences torque to failure in vertically oriented femoral neck fractures: a biomechanical study. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34:644–9.

Liu J, Zhang B, Yin B, Chen H, Sun H, Zhang W. Biomechanical evaluation of the modified cannulated screws fixation of unstable femoral neck fracture with comminuted posteromedial cortex. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:2584151.

Chen X, Zhang J, Wang X, Ren J, Liu Z. Incidence of and factors influencing femoral neck shortening in elderly patients after fracture fixation with multiple cancellous screws. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:1456–63.

Zlowodzki M, Brink O, Switzer J, Wingerter S, Woodall J Jr, Petrisor BA, et al. The effect of shortening and varus collapse of the femoral neck on function after fixation of intracapsular fracture of the hip: a multi-centre cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1487–94.

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the included studies for their help.

Funding

This work was supported by specific grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81902740, 81900846), the Scientific and technological personnel training project of Tianjin Health Commission (No. ZC20209), Science and technology project of Tianjin Health Commission (No. ZC20053) and Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine project of Tianjin Health Commission (No. 2021157).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZH, XLM and QD contributed to the study design. WT, CH, XMQ and XS contributed to the imaging analysis. ZH, JHB, WT, NNJ and DDC contributed to clinical follow-up. ZH, WT, CH and XS contributed to data analysis. ZH and WT contributed to the article writing. XLM and QD made the final decision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. All analyses were based on previous published studies; thus, no ethical approval and patient consent are required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Z., Taxi, W., Jia, H. et al. Multiple cannulated screw fixation of femoral neck fractures with comminution in young- and middle-aged patients. J Orthop Surg Res 17, 280 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03157-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03157-7