Abstract

Background

The decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment in intensive care units (ICUs) is influenced by ethical, cultural, and medical factors. This study focuses on a population of patients with hospital-acquired bloodstream infections (HABSI) to investigate the association between patient, pathogen, center and country-level factors and these decisions.

Methods

We analyzed data from the EUROBACT-2 study (June 2019–January 2021) from 265 centers worldwide, focusing on non-COVID-19 patients who died in the hospital or within 28 days after HABSI. We assessed whether death was preceded by a decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment, examining country, center, patient, and pathogen variables. To assess the association of each potentially important variable with the decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment, univariable mixed logistic regression models with a random center effect were performed.

Results

Among 1589 non-COVID-19 patients, 519 (32.7%) died, with 191 (36.8%) following a decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment. Significant geographical differences were observed, with no reported decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatment in African countries and fewer in the Middle East compared to Western Europe, Australia, and Asia. Once a center effect was considered, only health expenditure (Odds ratio 1.79, 95%CI: 1.45–2.21, p < 0.01) and age (Odds ratio 1.02, 95%CI: 1.002–1.05, p = 0.03) were significantly associated with decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatment, while other patient and pathogen factors were not.

Conclusion

Economic and regional disparities significantly impact end-of-life decision-making in ICUs. Global policies should consider these disparities to ensure equitable end-of-life care practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Up to 23% of patients die in the intensive care unit (ICU) worldwide, with decisions to forgo (withhold or withdraw) life-sustaining treatment (DFLST) preceding the majority of these deaths [1, 2]. The decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment in ICUs is influenced by a complex interplay of ethical, cultural, and medical factors [2,3,4]. The Ethicus-2 study, a worldwide study conducted between 2015 and 2016, including 12,850 patients who died or had limitation of treatments, highlighted significant regional variabilities in decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatment. In face of the considerable worldwide variation in end-of-life practices, the authors concluded that future research should investigate the causes of this variation with the aim to improve ethical practices. This was also highlighted in studies conducted in other former worldwide cohorts of various ICU patients [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Interestingly, a study highlighted that one of the factors associated with more DFLST was septic shock and pneumonia, suggesting that these practices seem to vary according to specific clinical conditions beyond country-level factors [3].

While these studies provide valuable insights, they also reveal the complexity and variability of DFLST due to the heterogeneous nature of the patient populations. By using the EUROBACT-2 cohort consisting of patients all admitted for hospital-acquired bloodstream infections (HABSI), we hypothesized that this approach would allow for a clearer understanding of the specific factors, including country, center, patient, and infection characteristics, that are associated with these critical DFLST.

Methods

EUROBACT-2 study design

We conducted a secondary analysis of the data from the EUROBACT-2 study, a prospective observational multicontinental cohort study conducted between June 2019 and January 2021. During this period, centers prospectively recruited patients, with a minimum of 10 consecutive HABSI patients or for a 3-month period [8]. Details on the study process, data collection, and variables can be found elsewhere [8]. Adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with a first episode of HABSI treated in the ICU were enrolled. A HABSI was defined as a positive blood culture sampled 48 h after hospital admission. Treatment in the ICU was defined as either the blood culture having been sampled in the ICU or the patient having been transferred to the ICU (i.e. in 48 h) for the treatment of the HABSI. For this analysis, we focused exclusively on non-COVID-19 patients who died in the hospital or within 28 days after HABSI. We focused on non-COVID-19 patients to avoid the confounding effects of the pandemic, in whom it has been shown that withholding therapies frequently preceded death [9].

The primary outcome of the present study was the occurrence of DFLST preceding death, which was a variable collected prospectively for every death in the EUROBACT-2 cohort.

Statistical analysis

First, a descriptive analysis of centers, patients' and pathogen’s characteristics according to the decision to forgo life-sustaining treatments was performed. Continuous variables were presented as median with interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables as number of patients (n) and percentage (%). Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used to detect differences in categorical variables, as appropriate, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables.

To identify factors associated with DFLST, we built a two-tiered hierarchical logistic mixed model. The effects of centre-based variables were included as random intercepts. We considered the hierarchical structure of the data, which may manifest as intraclass correlations. We performed univariable mixed logistic regression models to assess the association of each variable with DFLST.

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics Committee from the Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital Human Research (LNR/2019/QRBW/48376). Each study site then obtained ethical and governance approvals according to national and/or local regulations.

Results

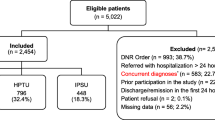

Among the 333 centers recruited in the EUROBACT-2 study, 68 centers were excluded as they either did not include non-COVID-19 patients or did not report any death at day 28. Of the 1589 patients, 519 (32.7%) died, of which 191 (36.8%) had a decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1).

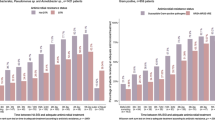

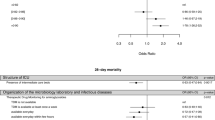

The median age was 65 (IQR 54–75), with 204 (39.3%) females. At the country level, significant geographical differences were noted (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1), with no DFLST reported in African countries and fewer in the Middle East compared to Western Europe, Australia and Asia. Patients with DFLST were more likely to be from countries with higher current health expenditure as a share of Gross Domestic Product (Supplementary Table 1). At the center level, patients with DFLST were less frequent in centers with open ICUs and higher patient-per-nurse ratios. At the patient level, patients with DFLST were older (median 67, IQR 58–76, vs. 64, IQR 51–75), but other factors such as Charlson comorbidity index, ICU admission reason, infection type, and mechanical ventilation use were not significantly different. No differences in pathogen groups were found between patients with DFLST and those without.

Proportion of hospital-acquired bloodstream infection mortality cases following a decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment. This map highlights the countries that reported Intensive Care Unit (ICU) deaths associated with Hospital-Acquired Bloodstream Infections (HABSI). The map displays the percentage of these deaths that occurred following a clinical decision to forgo life-sustaining treatment. Map created with Khαrtis (https://www.sciencespo.fr/cartographie/khartis/)

Using univariable mixed logistic regression analysis (Table 1), only gross current health expenditure as a share of Gross Domestic Product (OR 1.79, 95% CI: 1.45–2.21, p < 0.01) and older age (OR 1.02, 95% CI: 1.002–1.05, p = 0.03) were associated with DFLST.

Discussion

These findings, in a worldwide population of critically ill ICU patients with HABSI, highlight the importance of economic and regional disparities on patient outcomes and ethical decision-making in ICUs. Once a center effect was considered, only age and health expenditure were significantly associated with DFLST, underscoring the importance of geographical differences. Interestingly, pathogen factors and source of infection were not associated with DFLST in HABSI patients.

The Ethicus-2 study [2], conducted between 2015 and 2016, highlighted significant regional variability in decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatment. This was also evident in studies conducted in other cohorts, where heterogeneous patient populations, while allowing for generalizing their findings to overall ICU patients, could present more challenges identifying specific factors associated with DFLST [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Conducted five years after Ethicus-2, our study benefits from including more centers and offers a better representation of African countries. Despite the smaller sample size, it provides a detailed assessment of the variables that matter in terms of DFLST.

Past studies have found that patients' severity upon ICU admission and comorbidities were associated with more DFLST, a finding not observed in our study[3]. Interestingly, our study also found that infection and pathogen factors are not significantly associated with DFLST, reinforcing that variability in these decisions is primarily attributed to center and country effects. This can be explained by several hypotheses, including cultural, religious, and hospital policy differences, emphasizing the need for context-specific guidelines [1,2,3].

Regarding the importance of age after accounting for a center effect, our results align with previous studies [2, 3]. It appears that even in older patient populations, age continues to matter as a previous study focused on DFLST in old critically ill patients in European countries found that in this specific population, age, frailty, admission SOFA score, and country were the most significant variables associated with decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatments [10].

Our study has several limitations. Due to the sample size, we could not assess for the presence of variabilities in DFLST within a single country, which has been previously highlighted as being important [3]. Additionally, while our data spans multiple countries and centers, due to the limited sample size and secondary analysis nature of the study, it may not fully represent each region's diversity, indicating that further studies with broader representation of centers and populations are warranted. We could not distinguish between withdrawal and withholding of life-sustaining treatment, which might have provided more nuanced insights. The initial code status of the patient upon ICU admission was not available, which could be a significant factor in DFLST when, for example, limited time contracts with patients are made. Lastly, while our study has the advantage of reducing the variability related to different diseases, the heterogeneity of other studies allows for findings to be more generalizable across a broader range of ICU patients and conditions.

In summary, our study underscores the critical impact of regional and economic disparities on ethical decision-making in ICUs worldwide. Future research and global policy development should consider these disparities to enhance equity in end-of-life care practices across different settings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DFLST:

-

Decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatment

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- HABSI:

-

Hospital-acquired bloodstream infection

References

Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Ñamendys-Silva SA, François B, Martin-Loeches I, Lipman J, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):380–6.

Avidan A, Sprung CL, Schefold JC, Ricou B, Hartog CS, Nates JL, et al. Variations in end-of-life practices in intensive care units worldwide (Ethicus-2): a prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(10):1101–10.

Lobo SM, De Simoni FHB, Jakob SM, Estella A, Vadi S, Bluethgen A, et al. Decision-making on withholding or withdrawing life support in the ICU: a worldwide perspective. Chest. 2017;152(2):321–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.176.

Azoulay É, Metnitz B, Sprung CL, Timsit JF, Lemaire F, Bauer P, et al. End-of-life practices in 282 intensive care units: data from the SAPS 3 database. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(4):623–30.

Quill CM, Ratcliffe SJ, Harhay MO, Halpern SD. Variation in decisions to forgo life-sustaining therapies in US ICUs. Chest. 2014;146(3):573–82.

Mark NM, Rayner SG, Lee NJ, Curtis JR. Global variability in withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(9):1572–85.

Sprung L, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, Lippert A, Phelan D. End-of-life practices in European. JAMA. 2013;290(6):790–7.

Tabah A, Buetti N, Staiquly Q, Ruckly S, Akova M, Aslan AT, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care unit patients: the EUROBACT-2 international cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49(2):178–90.

Giabicani M, Le Terrier C, Poncet A, Guidet B, Rigaud JP, Quenot JP, et al. Limitation of life-sustaining therapies in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a descriptive epidemiological investigation from the COVID-ICU study. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):1–14.

Guidet B, Flaatten H, Boumendil A, Morandi A, Andersen FH, Artigas A, et al. Withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining therapy in older adults (≥ 80 years) admitted to the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(7):1027–38.

Acknowledgements

All investigators of the Eurobact-2 study group (see supplementary information).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Geneva. The Eurobact-2 database received research grants from the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients (ESGCIP), the Norva Dahlia foundation and the Redcliffe Hospital Private Practice Trust Fund. This report was prepared with no specific funding. H.W. is supported by the Training Fund of the Geneva University Hospitals. JDW is supported by a Sr Clinical Research Grant from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO, Ref. 1881020N). NB was supported by a Fellowship grant (grant number P400PM_183865).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: HW, AT, NB; Data curation: HW, NB; Methodology: HW, AT, JFT, NB; Project administration: AT, JFT, NB; Formal analysis and investigation: HW, NB; Writing—original draft preparation: HW; Writing—review and editing: HW, AT, JFT, NB, JdW; Validation: HW, AT, JT, JdW, NB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics Committee of the Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital Human Research (LNR/2019/QRBW/48376). Each study site then obtained ethical and governance approvals according to the local regulations in place.

Consent to participate and publication

Initial ethical approval as a low-risk research project with waiver of individual consent was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital, Queensland, Australia (LNR/2019/QRBW/48376). Each study site then obtained ethical and governance approvals according to national and/or local regulations.

Competing interests

JDW has consulted for Roche Diagnostics, Menarini, MSD, Pfizer, ThermoFisher and Viatris (fees and honoraria paid to institution). JFT reported advisory boards participation for Merck, Gilead, Beckton-Dickinson, Pfizer, Shionogi, Roche diagnostic, Advanz Pharma, research grants from Merck, Pfizer, Thermofischer.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wozniak, H., Tabah, A., De Waele, J.J. et al. Variability in forgoing life-sustaining treatment practices in critically Ill patients with hospital-acquired bloodstream infections: a secondary analysis of the EUROBACT-2 international cohort. Crit Care 28, 287 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-05072-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-05072-1