Abstract

Usutu virus is an emerging pathogen transmitted by mosquitoes. Culex modestus mosquitoes are widespread in Europe, but their role in disease transmission is poorly understood. Recent data from a single infectious mosquito suggested that Culex modestus could be an unrecognized vector for Usutu virus. In this study, our aim was to corroborate this finding using a larger sample size. We collected immature Culex modestus from a reedbed pond in Flemish Brabant, Belgium, and reared them in the laboratory until the third generation. Adult females were then experimentally infected with Usutu virus in a blood meal and incubated at 25 °C for 14 days. The presence of Usutu virus in the saliva, head and body of each female was determined by plaque assay and quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The transmission efficiency was 54% (n = 15/28), confirming that Belgian Culex modestus can experimentally transmit Usutu virus.

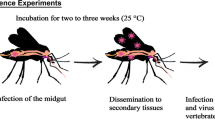

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Brief report

Usutu virus (USUV) is an emerging arthropod-borne virus endemic to Europe [1]. The virus cycles between avian reservoir hosts and intermediate mosquito vectors. USUV can spread rapidly, causing systemic disease and mass mortality in many bird species [2]. Humans can become incidental or dead-end hosts of USUV when bitten by an infected mosquito. The primary USUV vector is considered to be the Northern house mosquito Culex pipiens sensu lato (s.l.) [1]. In a recent study with field-collected Culex mosquitoes from Belgium, we observed that a Culex modestus mosquito could transmit USUV (20% transmission efficiency; n = 1/5), whereas the Culex pipiens form pipiens from the same study could not (0% transmission efficiency; n = 0/37) [3]. Whilst Culex pipiens s.l. have been shown to experimentally transmit USUV [4], we hypothesize that, in addition to Culex pipiens, Culex modestus is an important but so far unrecognized USUV vector. To follow up on our previous study, our aim was to corroborate these preliminary findings using a larger sample of Culex modestus.

We captured adult mosquitoes from July to August 2023 at a known Culex modestus habitat in Leuven, Belgium (Arenberg Park, N 50°51′46, E 4°41′01), as described in a previous article [3]. We were unable to capture sufficient mosquitoes for an experimental infection, as only 2.2% of adult mosquitoes captured over 25 trap nights were female Culex modestus (n = 2/91). We therefore opted to capture immature mosquitoes from a reedbed pond at the same location using dippers (John W. Hock Company, Gainesville, FL, USA). A total of 675 larvae and pupae were captured at Arenberg Park from August to October 2023. The immature mosquitoes were transported to the insectary facility and reared at 25 °C in plastic containers containing 500 ml tap water. Sprinkles of fish food (Tetramin®, Tetra, Spectrum Brands Pet, LLC, Blacksburg, USA) were provided daily until adult emergence. Of the surviving mosquitoes that emerged into adults, a total of 12 female and 10 male Culex modestus (n = 22/150) were identified using the key of Becker [5]. These mosquitoes were placed in 32.5 cm3 BugDorm cages (MegaView Science Co., Ltd., Taichung, Taiwan) at 25 °C and 70% relative humidity (RH) with access to 10% sucrose ad libitum on cotton pledgets. The females were given bowls containing water from their original breeding site to lay autogenous egg rafts, which were used to produce a subsequent generation. The larvae of Culex modestus were reared in breeding site water with sprinkles of fish food. This process was repeated until the third generation (F3) was reached. The F3 females were given 7–14 days to lay their autogenous egg rafts before offering them an infectious bloodmeal.

F3 female Culex modestus were taken to a biosafety-level 3 facility to determine their vector competence as described previously [3], with minor adaptations. Adult females of 7–14 days old were offered an infectious bloodmeal consisting of washed rabbit blood re-suspended with foetal bovine serum (FBS), 5 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and 1.0 × 107 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50)/ml USUV African lineage 3 (Grivegnée strain, passage 6, collected in Belgium [6]). A 69% feeding rate was observed (n = 44/64). The fed females were incubated at 25 °C and 70% RH for 14 days, after which saliva was collected from 28 surviving females. Individual mosquito bodies or the heads, wings and legs (combined) were placed in homogenate tubes containing 300 µl PBS and 2.8 mm Precellys ceramic beads (Bertin Technologies, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France). These samples were processed by homogenization (6800 rpm for 1 min) and filtration through a 0.8 µM filter. USUV infection was assessed as described previously by plaque assay on baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells [3]. All samples were incubated for 3 days to measure plaque forming units (PFU) per sample. RNA from the body and the head, wings and legs of each mosquito was extracted and quantified by qRT-PCR as described previously [3]. All figures were generated using GraphPad Prism v10.1.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA), and the illustrations in the graphical abstract were made using Procreate.com.

Most Culex modestus (60.7%) had a positive USUV infection in the abdomen with complete (100%) dissemination to the heads, wings and legs (Fig. 1). Of the mosquitoes with a disseminated infection, almost all had detectable, infectious USUV in their saliva (88.2%). Overall, the transmission efficiency of this Culex modestus population was 53.6%. These mosquitoes had a median USUV infectious titre of 5560 PFU/body [95% confidence interval (CI) 2110–17,800]; 778 PFU (95% CI 222–1780) in the head, wings, and legs; and 22 PFU (95% CI 16–32) in the saliva [Fig. 2A]. The bodies and the heads, wings and legs had a median titre of 1.84 × 107 (95% CI 1.09–2.82 × 107) and 5.43 × 106 (95% CI 1.25–7.94 × 106) viral genome copies, respectively (Fig. 2B). In our previous study, we observed a similar infection rate (60%, n = 3/5) but lower dissemination and transmission rates (dissemination: 66.7%, n = 2/3; transmission: 50%, n = 1/2) in Culex modestus experimentally infected with USUV-spiked chicken blood [3]. Although it is unclear how third-generation lab-reared mosquitoes differ from the field-collected, these results clearly indicate that Culex modestus from Belgium are capable of transmitting USUV.

The vector competence of Belgian Culex modestus for USUV. The proportion of USUV positivity (%) was determined by both plaque assay and qRT-PCR. IR infection rate (n with positive body/n total), DR dissemination rate (n with positive head, wings and legs/n with positive body), TR transmission rate (n with positive saliva/n with positive head, wings and legs), TE transmission efficiency (n with positive saliva/n total). Sample size is indicated above each bar

Infectious titres and viral genome copies in Culex modestus infected with USUV. A Plaque-forming units (PFU) in the mosquito body; head, wings and legs (H + W + L)M; and saliva samples. B Viral RNA genome copies in the mosquito body and the head, wings and legs (H + W + L). The bars represent the median with the interquartile range. LOD limit of detection

Similar to Culex pipiens form pipiens, Culex modestus are widespread across Europe, feed interchangeably between birds and humans, and can outlast the cold season by overwintering (reviewed elsewhere [7]). Culex modestus are considered primary vectors for West Nile virus in southern Europe [8,9,10] and potential vectors of parasitic heartworms (Dirofilaria immitis) [11], avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum) [12] and trypanosomes [13]. While eco-epidemiological data are needed to incriminate this species as a vector of USUV, this study using a third-generation (F3) Belgian field colony, our previous vector competence study using wild-type (F0) Belgian mosquitoes, and surveillance data from the Czech Republic [14, 15] indicate that Culex modestus are likely vectors of USUV.

Given the increasing evidence that Culex modestus is an important vector for human and animal pathogens, there have been few studies conducted on this species. A quick PubMed search yields only 122 results for “Culex modestus” from 1964 to June 2024. In comparison, these results are less than 4% of those obtained when searching “Culex pipiens” (3435 results as of June 2024). Future research on the transmission of USUV and other mosquito-transmitted pathogens in Europe should take Culex modestus into consideration.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in The Open Science Framework repository (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/QH4GA).

Abbreviations

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- BHK:

-

Baby hamster kidney

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DR:

-

Dissemination rate

- FBS:

-

Foetal bovine serum

- H + W + L:

-

Head, wings, and legs

- IR:

-

Infection rate

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PFU:

-

Plaque-forming unit

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RH:

-

Relative humidity

- s.l.:

-

Sensu lato

- TCID50 :

-

50% tissue culture infectious dose

- TE:

-

Transmission efficiency

- TR:

-

Transmission rate

- USUV:

-

Usutu virus

References

Clé M, Beck C, Salinas S, Lecollinet S, Gutierrez S, Van de Perre P, et al. Usutu virus: a new threat? Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268819001213.

Störk T, de Roi M, Haverkamp A-K, Jesse ST, Peters M, Fast C, et al. Analysis of avian Usutu virus infections in Germany from 2011 to 2018 with focus on dsRNA detection to demonstrate viral infections. Sci Rep. 2021;11:24191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03638-5.

Soto A, Coninck LD, Devlies A-S, Wiele CVD, Rosas ALR, Wang L, et al. Belgian Culex pipiens pipiens are competent vectors for West Nile virus while Culex modestus are competent vectors for Usutu virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17:e0011649. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011649.

Martinet J-P, Bohers C, Vazeille M, Ferté H, Mousson L, Mathieu B, et al. Assessing vector competence of mosquitoes from northeastern France to West Nile virus and Usutu virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17:e0011144. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011144.

Becker N, Petrić D, Zgomba M, Boase C, Madon M, Dahl C, et al. Mosquitoes and their control. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: Springer Nature; 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92874-4.

Benzarti E, Sarlet ML, Franssen M, Cadar D, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Rivas JF, et al. Usutu virus epizootic in Belgium in 2017 and 2018: evidence of virus endemization and ongoing introduction events. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2019.2469.

Soto A, Delang L. Culex modestus: the overlooked mosquito vector. Parasit Vectors. 2023;16:373. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05997-6.

Balenghien T, Vazeille M, Grandadam M, Schaffner F, Zeller H, Reiter P, et al. Vector competence of some French Culex and Aedes mosquitoes for West Nile Virus. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:589–95. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0266.

Tran A, L’Ambert G, Balança G, Pradier S, Grosbois V, Balenghien T, et al. An integrative eco-epidemiological analysis of West Nile Virus transmission. EcoHealth. 2017;14:474–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-017-1249-6.

Mughini-Gras L, Mulatti P, Severini F, Boccolini D, Romi R, Bongiorno G, et al. Ecological niche modelling of potential West Nile Virus vector mosquito species and their geographical association with equine epizootics in Italy. EcoHealth. 2014;11:120–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-013-0878-7.

Rossi L, Pollono F, Meneguz P, Cancrini G. [Four species of mosquito as possible vectors for Dirofilaria immitis piedmont rice-fields] – PubMed. Parassitologia. 1999;41:537–42.

Dimitrov D, Bobeva A, Marinov MP, Ilieva M, Zehtindjiev P. First evidence for development of Plasmodium relictum (Grassi and Feletti, 1891) sporozoites in the salivary glands of Culex modestus Ficalbi, 1889. Parasitol Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-023-07853-z.

Svobodova M, Volf P, Votypka J. Trypanosomatids in ornithophilic bloodsucking Diptera. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:444–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/mve.12130.

Rudolf I, Bakonyi T, Šebesta O, Mendel J, Peško J, Betášová L, et al. Co-circulation of Usutu virus and West Nile virus in a reed bed ecosystem. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1139-0.

Hönig V, Palus M, Kaspar T, Zemanova M, Majerova K, Hofmannova L, et al. Multiple lineages of Usutu virus (Flaviviridae, flavivirus) in blackbirds (Turdus merula) and mosquitoes (Culex pipiens, cx. modestus) in the Czech Republic (2016–2019). Microorganisms. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110568.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mariyam Mustajab, Kristien Minner, Xin Zhang, Arjen Wauters and Rémi Doré for their help with the immature mosquito collections and to Aboubakar Sanon for his assistance in the lab. We thank Prof. Mutien Garigliany from the University of Liège for providing the USUV strain. Thank you to the Space and Real Estate Division at KU Leuven for kindly allowing us to capture mosquitoes at Arenberg Park. We also thank Prof. Johan Neyts for allowing us the use of his lab space.

Funding

Funding was awarded internally by KU Leuven (Grant ID: C14/20/108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D. and A.S. conceived and designed the study. L.W. and A.S. reared and supplied the mosquitoes. A.S. performed the data collection. A.S. analysed the data. A.S. wrote the paper. L.D. contributed to the editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Rabbit blood was obtained under the approval of the Ethical Committee of the University of Leuven (license P150/2018) following institutional guidelines approved by the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Soto, A., Wauters, L. & Delang, L. Is Culex modestus a New Usutu virus vector?. Parasites Vectors 17, 285 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06360-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06360-z