Abstract

Background

High levels of satisfaction among women with the antenatal care services will increase the compliance of antenatal visits during pregnancy. Thus, this study was done to assess the level of satisfaction among women on the quality of antenatal care received and the factors influencing thereof.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in the three zones of Sarawak. Women aged 18 years and above, irrespective of ethnic groups, having children aged 3 years and below were included in the study. Data was collected by face-to-face interview using interview schedule. A validated Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18) was used to assess the satisfaction with antenatal care. A total of 1236 data was analysed using IBM SPSS version 22.0. A p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

A multinomial logistic regression analysis revealed that Bidayuh 17.4 % was less likely to be highly satisfied with antenatal care. Similarly, respondents with secondary level of education 29.9 % were less likely to be highly satisfied, whereas, respondents having primary level of education, 1.6 % were less likely to be highly satisfied. However, those who did not spend any money as out of pocket expenses were 1.935 times more likely to be highly satisfied with antenatal care.

Conclusion

Overall the studied women were satisfied with the antenatal care services. Ethnicity, level of education and out of pocket expenses appeared to be important predictors of satisfaction with antenatal care. The finding recommends the community-based and language-specific interventions should be implemented to sustain the satisfaction of maternal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

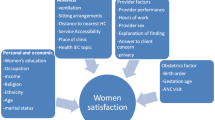

Utilization or antenatal visit has been shown to improve birth outcome as well as the maternal outcome during pregnancy-related events, giving a positive impact when the visit frequency and care are adequate (Garrido 2009). The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended a minimum of four (4) antenatal visits per pregnancy for an optimal birth outcome and to reduce maternal risks per pregnancy, especially, for developing countries (AbouZahr and Wardlaw 2003). Satisfaction has been one of the outcome measures of quality of care as well (Koblinsky et al. 1999). Satisfaction studies on maternal health services, particularly antenatal service have been carried out as a measurement of outcomes of public health policies. It is also an indirect reflection of the quality of antenatal care service provided to the patients (Hasan et al. 2007), their experience and their role as end-users in the health care system, such as the satisfaction study done in National University Hospital, Kuala Lumpur (Pitaloka and Rizal 2006) and in community-based study in Vietnam (Tran et al. 2012). Health care provider factors such as private care versus government clinics have also been studied showing a higher satisfaction in the private care (Nketiah-Amponsah 2009; Zeine et al. 2010), caregivers’ positive attitude (Zeine et al. 2010; Hildingsson and Radestad 2004; Esimai and Omoniyi-Esan 2009; Ghobashi and Khandekar 2008; Davey et al. 2005), continuity of care (Nketiah-Amponsah 2009; Davey et al. 2005; Biró et al. 2003; Fan et al. 2005), distance (Nketiah-Amponsah 2009) and short waiting time (Esimai and Omoniyi-Esan 2009), but long duration with care givers (Ghobashi and Khandekar 2008; Davey et al. 2005), have been shown to increase the satisfaction of patients receiving antenatal care services. Other than the health care providers aspect, maternal age has been shown to affect the satisfaction of antenatal service, with young mothers aged less than 25 years (Hasan et al. 2007) being more satisfied while some studies showed that older mothers aged more than 30 years (Zeine et al. 2010; Yohannes et al. 2013) were more satisfied with the services and were factors associated with utilization of service (Zeine et al. 2010). The level of education is another determining factor influencing satisfaction with antenatal care services (Hasan et al. 2007; Nketiah-Amponsah 2009; Zeine et al. 2010; Yohannes et al. 2013). Other family related factors are family size (Zeine et al. 2010), household income and costs per antenatal visit (Zeine et al. 2010; Overbosch et al. 2004). In developed countries such as in Sweden (Hildingsson and Radestad 2004) and developing countries such as Vietnam (Tran et al. 2012) and Malaysia (Pitaloka and Rizal 2006), the frequency of antenatal visit itself was the determinants of satisfaction, whereby higher numbers of visit increased the satisfaction of antenatal services. The significance of this study towards the current knowledge of antenatal care services was in identifying the different domains of antenatal service provision in which the women were satisfied with; as well as identifying the factors affecting the level of satisfaction among the women, which would increase the compliance and usage of maternity services. Thus, in this context, the main objective of this study was to determine the factors associated with the level of satisfaction among women visiting the Mother and Child Health clinics in Sarawak during their last pregnancy.

Methods

Study design and sampling procedure

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in three (3) different divisions of the eleven divisions in Sarawak. Every three (3) out of five (5) villages were selected through the Mother and Child Health Clinic registry. A multi-stage cluster random sampling was used for sampling procedure. All households of the villages with mothers having the youngest child of 3 years and below were visited. All respondents who did not consent or unwilling to participate; aged below 18 years; non-Malaysian citizenship; incapable of answering the questionnaires were excluded from the study. A total of 1400 households were selected initially, however, a total of 1236 women gave their consent for participation.

Instrument development and data collection procedure

A modified data collection instrument was developed based on Demographic Health Survey (DHS) (Pitaloka and Rizal 2006), PSQ-18, (Marshall and Hays 1994) and others relevant instruments (Sarawak State Health Department 2003; Rahman 1997). Data collection was done using an interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of four main parts, which were (1) socio-demographic characteristics and the variables were maternal age, ethnicity, level of education, occupation, household income and family size. (2) Antenatal care history, and the variables were number of antenatal visits, gestational age at booking, antenatal attendant, time required to reach the clinic and out of pocket expenses, (3) delivery care history and (4) postnatal care history. For each maternity care services, patient satisfaction questions were asked regarding the services received. The level of satisfaction with antenatal care was determined by seven domains of satisfaction. Each domain has Likert’s scale questions. After summation of all domains score, it was checked for normality. The satisfaction score was divided into quartiles. The lowest quartile as poor and middle two quartiles as average and the last quartile categorized as highly satisfied with antenatal care. In the current analysis, only antenatal care history was considered. Before field operation, a pre-test of the questionnaire was done in a non-sample area with the translated National language (Bahasa Malaysia) questionnaire. A minor change was made following pre-test of the questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

The study proposal was approved by the Technical Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS) and the National Medical Research Registry (NMRR). Ethical clearance was also obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and Institute of Public Health, Malaysia. Informed written consent was obtained from the respondents before data collection. The respondents were also assured of data confidentiality.

Data processing and analysis

After data collection, the data were checked manually for completeness and inconsistencies. Data entry and analysis was by IBM SPSS version 22.0 (Corp 2013). Missing data were carefully examined and was imputed by SPSS. After validation, descriptive analysis was done and descriptive statistics were presented in frequency tables. A multinomial logistic regression analysis was done to identify factors affecting the level of satisfaction with antenatal care (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013). A p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

The mean (SD) age was 28.3 (6.1) years ranging from 18 to 49 years. The highest percentage of them were Iban (40 %) followed by Bidayuh (30.3 %) and Malay (17.7 %). More than two-thirds (69.5 %) were Christian followed by Muslim (27.3 %). The highest percentage of respondents had secondary level of education (69.7 %) followed by higher secondary and above (16.9 %). The majority of them were housewives (76.9 %) and the rest were engaged in service or other jobs. The median income was MYR 1000 and the average family size was 5.9 (Table 1).

Characteristics of antenatal care

The majority of the respondents made more than nine antenatal visit during their last pregnancy (72.2 %) followed by 5–8 times (20.8 %) and only 7 % had 1–4 times antenatal visits. Three-fifths (60.9 %) of them booked antenatal visit before the third month followed by another one-third (32.4 %) who booked between 3 and 5 months of gestation. Half of them were attended by a nurse (50.9 %). However, two-fifths (38.1 %) were attended by both doctor and nurse. On an average 18 min were required to attend the clinic. About three-fifths (57.5 %) were attended to within 15 min. It was reported that one-fifth (18.9 %) did not have any out of pocket expenses. However, about half (48.7 %) had spent 11–50 ringgit per visit (Table 2).

Factors affecting satisfaction on antenatal care: multinomial logistic regression analysis

A multinomial logistic regression was done to examine the factors affecting the level of satisfaction with antenatal care in which the satisfaction score was divided into three groups based on quartile score (poor, average and highly satisfied). It was found that 24.6 % were poorly satisfied and considered as reference category and 51 % had the average satisfaction and another 24.6 % were highly satisfied with antenatal care. Initially, all the explanatory variables were analyzed with the level of satisfaction using Chi square test of independence. The variables that were statistically significant in Chi square test were entered into mutinomial logistic regression model (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013). In the final model, ethnic group, level of education, and out of pocket expenses appeared to be important predictors of the level of satisfaction with antenatal care (p < 0.05). The full model showed that it was statistically significant χ2(24, 1211) = 50.014; p < 0.001 indicating that the model was able to distinguish between respondents who were satisfied and unsatisfied with the antenatal care. This model contains the four independent variables explained between 4.0 % (Cox and Snell R square) and 4.6 % (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in the level of satisfaction. It was also able to classify 51.4 % of the cases. The goodness of fit indices was not statistically significant [Chi square (df) = 269.042(256); p > 0.05] which indicated good fitted model.

Analysis indicated that Bidayuh 17.4 % were less likely to be highly satisfied with antenatal care. Similarly, respondents with secondary level of education 29.9 % were less likely to be highly satisfied, whereas, respondents having primary level of education, 1.6 % were less likely to be highly satisfied. Regarding, out of pocket expenses, those who did not spend any money were 1.935 times more likely to be highly satisfied with antenatal care (Table 3).

Discussion

The maternal age in this study was highest in the age range of 20–29 years old, with the mean age of 28.3 years, showing a younger age group. A similar result was found in a study in Kuala Lumpur with a median of 29 years (Pitaloka and Rizal 2006). Peculiar to this study was the ethnic makeup, with two-thirds were from the indigenous races of Sarawak known also as Dayak, compared to studies done in Peninsula Malaysia with the majority of Malays, Chinese and Indians (Pitaloka and Rizal 2006). Minimal tertiary level education and housewives show similar findings as found in other countries with a rural setting such as in Bangladesh (Hasan et al. 2007), Egypt (Montasser et al. 2012), Ethiopia (Zeine et al. 2010), India (Khanam et al. 2012) and Asian countries such as Vietnam (Tran et al. 2012). Even though the highest income group was below the recommended minimal monthly income of MYR 850, the mean was MYR 143.04 and the median was MYR 1000 showing the patterns of rural socioeconomic status. However, this was lower as compared to the national census of mean household income of RM 3080 in rural Malaysia (Department of Statistics, Malaysia 2012). The median family size was 5, with an average of four children. This was in accordance with the declining fertility rate, which was encountered by the researcher during community survey as well as findings from the literature regarding reducing the fertility rate in Malaysia (Yadav 2012).

The characteristics of antenatal care received during last pregnancy revealed that the majority of them visited, at least, the state-recommended total of eight visits per pregnancy, which was similar to a high number of antenatal visits in developed countries such as in the United Kingdom (Redshaw and Heikkila 2010) and Sweden (Hildingsson et al. 2002). Two-thirds of the women visited the MCH clinic before 3 months of gestational age, which was also similar to Vietnam (Tran et al. 2012) and United Kingdom (Redshaw and Heikkila 2010). The median distance to the nearest MCH clinic was 15 min, closer distance compared to Bangladesh (Hasan et al. 2007), but similar to Tanzania whereby the nearest clinic was located in the village itself (Rockers et al. 2009). Understandably, more than three-quarters of the respondents used their own transport for follow-up; with the median amount of MYR 37.00 per visit.

The level of satisfaction with antenatal care services in this study was high, similar to other studies done in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Pitaloka and Rizal 2006) Oman (Ghobashi and Khandekar 2008), Bangladesh (Hasan et al. 2007), United Kingdom (Redshaw and Heikkila 2010), Ethiopia (Esimai and Omoniyi-Esan 2009) and Scotland (Teijlingen et al. 2003). Even though they were satisfied with the waiting hours, however, they were less satisfied with the duration spent during consultation and treatment with medical staff, similar to findings in an urban antenatal clinic setting in Kuala Lumpur (Pitaloka and Rizal 2006) and in developed countries such as Oman (Ghobashi and Khandekar 2008).

Ethnicity, level of education, and out of pocket expenses appeared to be important factors for satisfaction on antenatal care. The studies done in developing countries such as in Nigeria and Oman also showed similar findings of race affecting the level of satisfaction on antenatal care services (Ghobashi and Khandekar 2008; Oladapo et al. 2008). Travailing far to the nearest clinic has been shown to reduce the level of satisfaction found in previous studies in Ghana (Overbosch et al. 2004) and Vietnam (Tran et al. 2012). There have been mixed findings regarding the level of education affecting satisfaction among women in antenatal care services. The lower level of education was associated with dissatisfaction such as in Sweden (Hildingsson and Radestad 2004), whereas tertiary and higher education were associated with high satisfaction levels as found in Nigeria (Esimai and Omoniyi-Esan 2009) and Ethiopia (Yohannes et al. 2013).

This study identified several limitations such as the cross-sectional design of this study and the dependence on recall memory of the respondents. The strength is its state-wide implementation where the respondents were recruited mainly from villages in the suburban and rural communities. This allows the findings to represent the community in these areas of Sarawak.

Conclusion

Overall, women were satisfied with the antenatal care services provided in the maternal and child health clinics in Sarawak. The finding that the diversified cultural society in Sarawak showed disparity in the level of satisfaction with antenatal care needs further exploration. The finding suggests that health education and public health program interventions should be more focused to local settings, which are community-oriented and culturally suited language-specific approach, and not a ‘one size fit all’ approach for maternal health-related programs. Current “no-fee charges” for antenatal care services in Malaysia should be maintained, as the mother still prefer free services.

References

AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T (2003) Antenatal care in developing countries: promises, achievements and missed opportunities-an analysis of trends, levels and differentials, 1990–2001. World Health Organization, Geneva

Biró MA, Waldenström U, Brown S, Pannifex JH (2003) Satisfaction with team midwifery care for low-and high-risk women: a randomized controlled trial. Birth 30(1):1–10

Corp IBM (2013) IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. IBM Corp, Armonk

Davey MA, Brown S, Bruinsma F (2005) What is it about antenatal continuity of caregiver that matters to women? Birth 32(4):262–271

Department of Statistics, Malaysia (2012) Household income and basic amenities survey report 2012. Retrieved from https://newss.statistics.gov.my/newss-portalx/ep/epLogin.seam?lang=en

Esimai OA, Omoniyi-Esan GO (2009) Wait time and service satisfaction at Antenatal Clinic, Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife. East Afr J Public Health 6(3):312–314

Fan VS, Burman M, McDonell MB, Fihn SD (2005) Continuity of care and other determinants of patient satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med 20(3):226–233

Garrido GG (2009) The impact of adequate prenatal care in a developing country: testing the WHO recommendations. California Center for Population Research On-Line Working Paper Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1879464

Ghobashi M, Khandekar R (2008) Satisfaction among expectant mothers with antenatal care services in the Musandam Region of Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 8(3):325

Hasan A, Chompikul J, Bhuiyan SU (2007) Patient satisfaction with maternal and child health services among mothers attending the maternal and child health training institute in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Public Health Dev 5(3):23–33

Hildingsson I, Radestad I (2004) Swedish women’s satisfaction with medical and emotional aspects of antenatal care. J Adv Nurs 52(3):239–249

Hildingsson I, Waldenström U, Adestad I (2002) Women’s expectations on antenatal care as assessed in early pregnancy: number of visits, continuity of caregiver and general content. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81(2):118–125

Khanam N, Syed ZQ, Wagh V (2012) Patient satisfaction on maternal and child health services. Indian Med Gaz 1(1):47–51

Koblinsky MA, Campbell O, Heichelheim J (1999) Organizing delivery care: what works for safe motherhood? Bull World Health Organ 77(5):399

Marshall GN, Hays RD (1994) The patient satisfaction questionnaire short-form (PSQ-18). Rand Santa Monica, CA

Montasser NAE, Helal RM, Megahed WM, Amin SK, Saad AM, Ibrahim TR, Elmoneem MA (2012) Egyptian women’s satisfaction and perception of antenatal care. Int J Trop Dis Health 2(2):145–156

Nketiah-Amponsah E (2009) Determinants of consumer satisfaction of health care in Ghana: does choice of health care provider matter? Glob J Health Sci 2:50–61

Oladapo OT, Iyaniwura CA, Sule-Odu A (2008) Quality of antenatal services at the primary care level in Southwest Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 12(3):71–92

Overbosch GB, Nsowah-Nuamah NNN, Van Den Boom GJM, Damnyag L (2004) Determinants of antenatal care use in Ghana. J Afr Econ 13(2):277–301. doi:10.1093/jae/ejh008

Pitaloka SD, Rizal AM (2006) Patients’ satisfaction in Antenatal Clinic Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Jurnal Kesihatan Masyarakat (Malaysia) 12(1):9–18

Rahman MM (1997) Socio-demographic determinants of infant mortality and morbidity and its correlation with maternal health in slum dwellers of Dhaka City. Dhaka University, Bangladesh

Redshaw M, Heikkila K (2010) Delivered with care: a national survey of women’s experience of maternity care. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford

Rockers PC, Wilson ML, Mbaruku G, Kruk ME (2009) Source of antenatal care influences facility delivery in rural Tanzania: a population-based study. Matern Child Health J 13(6):879–885

Sarawak State Health Department (2003) Klinik Kesihatan. Management manual, 4th edn. Sarawak State Health Department, Kuching

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2013) Using multivariate statistics, 6th edn. Pearson Education Inc, Supper Saddle River

Teijlingen ER, Hundley V, Rennie AM, Graham W, Fitzmaurice A (2003) Maternity satisfaction studies and their limitations: “what is, must still be best”. Birth 30(2):75–82

Tran KT, Gottvall K, Nguyen HD, Ascher H, Petzold M (2012) Factors associated with antenatal care adequacy in rural and urban contexts-results from two health and demographic surveillance sites in Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res 12(40):1–10. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-40

Yadav H (2012) A review of maternal mortality in Malaysia. IeJSME 6(Suppl 1):S142–S151

Yohannes B, Tarekegn M, Paulos W (2013) Mothers’ utilization of antenatal care and their satisfaction with delivery services in selected public health facilities of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Sci Technol Res 2(2):74

Zeine A, Mirkuzie W, Shimeles O (2010) Factors influencing antenatal care service utilization in Hadiya Zone. Ethiop J Health Sci 20(2):75–82

Authors’ contributions

DPN and MMR, designed the study. DPN was responsible for data collection, she and MdMR, involved in data analysis and drafted the paper. MTA, edited and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support and help of the Divisional Health Office of Kuching, Sibu, Betong and Miri Division. We are also indebted to the villagers who had kindly participated in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, M.M., Ngadan, D.P. & Arif, M.T. Factors affecting satisfaction on antenatal care services in Sarawak, Malaysia: evidence from a cross sectional study. SpringerPlus 5, 725 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2447-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2447-3