Abstract

Background

A delay presentation for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patient’s care (that is late engagement to HIV care due to delayed HIV testing or delayed linkage for HIV care after the diagnosis of HIV positive) is a critical step in the series of HIV patient care continuum. In Ethiopia, delayed presentation (DP) for HIV care among vulnerable groups such as tuberculosis (Tb) /HIV co-infected patients has not been assessed. We aimed to assess the prevalence of and factors associated with DP (CD4 < 200 cells/μl at first visit) among Tb/HIV co-infected patients in southwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A retrospective observational cohort study collated Tb/HIV data from Jimma University Teaching Hospital for the period of September 2010 and August 2012. The data analysis used logistic regression model at P value of ≤ 0.05 in the final model.

Results

The prevalence of DP among Tb/HIV co-infected patients was 59.9 %. Tb/HIV co-infected patients who had a house with at least two rooms were less likely (AOR, 0.5; 95 % CI: 0.3–1.0) to present late than those having only single room. Tobacco non-users of Tb/HIV co-infected participants were also 50 % less likely (AOR, 0.5; 95 % CI: 0.3–0.8) to present late for HIV care compared to tobacco users. The relative odds of DP among Tb/HIV co-infected patients with ambulatory (AOR, 1.8; 95 % CI, 1.0–3.1) and bedridden (AOR, 8.3; 95 % CI, 2.8–25.1) functional status was higher than with working status.

Conclusions

Three out of five Tb/HIV co-infected patients presented late for HIV care. Higher proportions of DP were observed in bedridden patients, tobacco smokers, and those who had a single room residence. These findings have intervention implications and call for effective management strategies for Tb/HIV co-infection including early HIV diagnosis and early linkage to HIV care services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Multilingual abstract

Please see Additional file 1 for translations of the abstract into the six official working languages of the United Nations.

Background

HIV care continuum is a series of steps from the time a person is diagnosed with HIV through assessment for antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility, retention in care, and immunologic success and virologic suppression via treatment adherence [1]. A myriad of activities have been devoted to mitigate negative HIV outcomes in the continuum [2]. Nevertheless, challenges exist at every step of the continuum. Timely HIV testing is the first critical step in effective HIV care and prevention [3]. HIV infected persons fail to get tested due to various factors. Thus include: being unaware of their risk of contracting infection or importance of getting oneself tested and not being able to access care promptly once they test positive [4, 5]. Hence, delayed presentation for HIV care (DP) can either be due to delay in HIV testing or delay in linkage with or in accessing the HIV care.

There is little consensus on what should be considered DP, and several definitions have been used to date. Some have defined DP when the diagnosis of an AIDS defining condition occurs either before or concomitantly to an HIV diagnosis [6], during the subsequent six months [5, 7] or during the following year of an HIV diagnosis [8]. Other definitions of DP use CD4 cell count of < 200 [9] or < 350 [10] cells/μl. The 1993 expanded AIDS surveillance case definition measured DP if persons present with a CD4 cell count < 200 cells/μl and/or with an AIDS defining disease [11].

DP has several consequences including: (i) increased risk of progression of the infection; ii) increased risk of HIV transmission with severe public health implications [12]; iii) facilitation of immunological failure and treatment failure [13–15]; (iv) increased risk of poor treatment outcomes including early mortality [13–16]; and v) increased first line ART drug resistance due to multiplication and then mutation of the virus, and thereby switching to more expensive second line regimens [12]. In addition, DP also challenges the effectiveness of test-and-treat strategies [17]. Test-and-treat strategies for HIV care theorize that earlier testing and treatment of HIV infection could switch prominently with significantly ongoing HIV transmission and further curtail the HIV epidemic [17].

DP has been reported to be a significant problem across the world in developed and developing countries. In Europe for example, the prevalence of DP has been reported to be roughly between 15 and 66 % [18, 19]. Higher prevalence of 72–83.3 % [20, 21] has been reported from Asia. In Africa, 35–65 % report late for HIV care [22–25]. Reported barriers to DP among general population have include several factors including: age, sex, level of education, income, place of residence, perceiving HIV as curable, HIV related stigma, co-morbidity, having contact with female sex workers, alcohol users, chewing chat, smoking cigarette, perceived risky sexual behaviour, pre-and post-test counseling [4, 15, 20, 21, 26, 27].

While there have been no appropriate studies to estimate the prevalence of DP in Ethiopia, a situational analysis conducted in southwest part of the country reported that 33.1 % of patients from a health center and 38.4 % of patients from a hospital presented late for the care [28]. A few studies have assessed reasons for DP among the general HIV population [4, 15, 27]. However, there is a lack of studies that have explored DP among vulnerable groups such as tuberculosis (Tb) /HIV co-infected patients.

Tb and HIV, the most important infectious diseases of our era, are inextricably linked [29]. HIV-1 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.Tb) are both intracellular pathogens having a potential to interact at different levels such as population, clinical, and cellular [30]. Their co-infection causes serious bidirectional effect than one causes alone [30]. Both cause synergistic combination of illness in which HIV promotes the progression of latent Tb infection to disease, and Tb accelerates the progression of HIV disease to poor prognosis including death [31]. In addition, HIV has been ascribed as the principal factor for failure to meet Tb control targets in HIV endemic settings, and Tb is a key cause of death among people living with HIV in similar settings [32]. Given the above facts, DP among Tb/HIV co-infected patients should be given a top priority in order to curb both scourges. This study aimed to assess the prevalence of and factors associated with DP among Tb/HIV co-infected patients.

Methods

Design and population

A retrospective observational cohort study was undertaken between August and October 2013 using records from September 01, 2010 to August 31 2012 in ART clinic at Jimma University Teaching Hospital (JUTH). JUTH is situated in Jimma zone, 357 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The zone has an estimated population of 2 486 155 people of which 89.69 % are rural inhabitants [33].

Jimma is found in a regional state (Oromia) that accounted for the highest number of HIV infected people from Ethiopia with 224 000 people. It is near Gambella region, a regional state that had the highest prevalence rate of HIV from Ethiopia with 6 % [34]. There is a large refugee camp near Jimma. Refugees from many African countries pour into this camp. The movement of these people to and from the city increases the risk of HIV infection and Tb in both the city and the camp. In Jimma, primary healthcare services, including diagnosis and treatment of Tb, voluntary counseling and testing (VCT), prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT), ART and opportunistic infections (OIs) treatment services are available. All patients aged ≥15 years and who had access to Tb/HIV medical treatment at JUTH were the target population.

Data source

JUTH has an electronic patient database called Comprehensive Care Centre Patient Application Database (C-PAD). C-PAD is Electronic Medical Records or EMR system database that contains patients’ both clinical and non-clinical information. This was the main source of data in this study. Data were extracted using a data extraction check list from the database. Data clerks immediately informed the clinicians if any data was missing, and weekly EMR-generated patient summary reports help to flag patients with conditions that needed follow-up. When data were incomplete, we tried to refer the patients’ cards, registration and log books.

Study variables

Delayed presentation for HIV care is the response variable and was dichotomized as delayed and early. DP refers to HIV positive individuals aged 15 years and above having the CD4 lymphocyte count of less than 200/μl irrespective of clinical staging at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics of the institution. Early presentation for HIV care refers to HIV positive individuals aged 15 years and above having the CD4 lymphocyte count of ≥ 200/μl irrespective of clinical staging at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics of the institution.

The explanatory variables included age, sex, educational level, marital status, occupation, residence, number of people living in the household, accessibility to safe water, accessibility of electricity, number of bedrooms in the household, functional status, disclosure, condom use, risky sexual behavior, tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, Tb type and mode of entry. Level of education was classified as illiterate (could not read and write), read and write only (could read and write but had received no formal education) and formal education (received formal education starting from grade one). Functional status was categorized as work (able to perform usual work), ambulatory (able to perform activity of daily living) and bedridden (not able to perform activity of daily living). Mode of entry was the mode of anti-Tb treatment entry of patients and was categorized as new, relapse and dropout.

Data analyses

Data exploration, editing and cleaning were undertaken before analysis. The analysis of both descriptive and inferential statistics was conducted. Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation values for continuous data; percentage and frequency tables for categorical data. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with DP. Bivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to see the existence of crude association and select candidate variables (with P value below 0.25) to multiple logistic regression. We checked multi-collinearity among selected independent variables via variance inflation factor (VIF) and none was found. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered as a cut point for statistical significance in the final model. Fitness of goodness of the final model was checked by Hosmer and Lemeshow test and was found fit. The data was summarized using odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 21 for mackintosh.

Results

Demographic characteristics of study participants

Two hundred and eighty nine (289) Tb/HIV co-infected patients were registered for HIV care during the period between September 2010 and August 2012 in JUTH (Fig. 1), but 17 records were incomplete in all data sources. Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of the 272 Tb/HIV co-infected respondents. The majority of the study participants were between 25 and 34 years with a mean age of 32 (±8.53) years, and females accounted for more than half (58.1 %) of the study participants. About half (51.4 %) of the respondents followed Muslim religion and one third (31.6 %) of participants represented daily laborers. More than half of the population (51.5 %) had formal education and two third (60.7 %) of the respondents were married. Urban dwellers were over-represented (70 %).

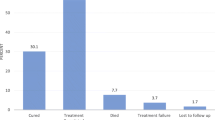

Prevalence of delayed presentation for HIV care and characteristics of delayed presenters

A total of 163 (59.9 %) Tb/HIV co-infected patients were categorised as delayed presenters for HIV care during the study period. Table 2 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of DP. Tb/HIV participants aged between 25 and 34 years, and 35 and 44 years contributed for 46.6 % and 28.2 % of DP proportion respectively. Females accounted for more than half (55.8 %) of DP. DP was also higher among married (61.3 %) compared to single (20.9 %) study participants. DP was very high among occupants with economic hardship. Farmers and daily laborers formed 32.5 and 27 % of DP amongst the study participants respectively. When analyzed by level of education, about half (48.5 %) of the participants who presented late for HIV care were formally educated whereas one third (30.1 %) were illiterate. The remaining delayed presenters were noted as being able to read and write but did not have formal education. Two third (66.9 %) of delayed presenters were urban dwellers.

Among the delayed presenters, 77 (47.2) and 55 (33.7 %) study participants had houses with single and double bedrooms respectively; whereas households with four bedrooms accounted for only 4.9 % of delayed presenters. A fifth, i.e. 20.2 and 21.5 % of delayed presenters did not have water and electricity in their households. An additional 21.5 % of delayed presenters were seriously ill and bedridden. The majority (75.5 %) of delayed presenters had pulmonary Tb type followed by mixed type (19 %). Tb/HIV participants who were exposed to risky behaviors such as having multiple sexual partners accounted for 69.3 % of DP.

Factors associated with delayed presentation for HIV care

Age, occupational status, place of residence, number of rooms per household, availability of safe water, smoking tobacco and functional status had P-value ≤ 0.25 in bivariate logistic regression and were candidates for multiple logistic regression (Table 2).

Table 3 presents the multiple logistic regression analysis with DP. Logistic regression analyses demonstrated the following were associated with DP: number of rooms per household, being recorded as tobacco user and being recorded as ambulatory or bedridden functional status. Tb/HIV co-infected patients who had houses with double rooms were less likely (AOR, 0.5; 95 % CI: 0.3–1.0) to present late than those having only single room. Tobacco non-users of Tb/HIV co-infected participants were also 50 % less likely (AOR, 0.5; 95 % CI: 0.3–0.8) to present late for HIV care compared to tobacco users. The relative odds of DP among patients with working status was lower compared to patients with bedridden (AOR, 8.3; 95 % CI, 2.8–25.1) and ambulatory (AOR, 1.8; 95 % CI, 1.0–3.1) status.

Discussion

The UNAIDS 90-90-90 goal for 2020 aims to of diagnose 90 % of people living with HIV, provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) to 90 % of those diagnosed and achieve 90 % viral load suppression among those on treatment [35]. The trend of expansion of HIV care services particularly ART treatment in Ethiopia is promising. ART program was expanded from four facilities in 2003 to 913 in 2013, and the number of people on ART has increased from 900 at the beginning of 2005 to 270,460 in 2012 [36, 37]. However, not much attention has been given to prevent DP for the vulnerable groups particularly Tb/HIV co-infected patients which remains one of the vastest defies in the reduction of HIV infection in resource scare countries including Ethiopia. Nearly 60 % of the patients in our study were delayed presenters, a finding that is similar with a study conducted in Zimbabwe [38]. This is also a comparable magnitude with DP of general HIV population in Africa [22, 26].

However, in Ethiopia, the prevalence of DP among TB/HIV co-infected patients according to the current study is about twice as compared to the previous finding conducted among general HIV population [4]. This indicates that the prevalence of DP among Tb/HIV co-infected patients is a considerable number. This is against the current treatment guidelines of WHO and Ethiopia that advocate early commencement of ART among Tb/HIV co-infected patients [32, 39, 40]. Such an impediment to engage for HIV care poses a sizeable obstacle to the successful implementation of strategies that suggest “test” (i.e. early identification of all HIV-infected individuals) and “treat” (i.e. initiation of antiretroviral therapy in these individuals) [41–43]. Previous studies confirmed that “test” and “treat” strategy could have dramatic reductions in the incidence of HIV infection and transmission [41–43].

The timing of ART treatment initiation among Tb/HIV co-infected patients is critically important for the favorable therapeutic outcomes and patient care [39]. According to the current guidelines, ART should be started within 2–8 weeks after commencement of anti-Tb treatment [44]. Nevertheless, the issue of when to start ART in Tb patients has been debatable [45, 46]. Early or concurrent starting of ART may lead to high pill burden, clinical debilitation due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), toxicity of drugs, decrease drug compliance, worsening of ailment, and finally demise [45, 46]. To the contrary, late commencement of ART may lead to exacerbation of ailment and death [45, 46].

Findings of a previous study conducted in Zimbabwe [38] depicted that being treated for Tb first time, staying more than 5 km from a clinic, and having a family member on ART were factors for delayed ART initiation. In addition, findings of another study from Malawi [47] revealed that cost of transport to the hospital ART site was significantly associated with ART acceptance. This indicates that ART acceptance among Tb patients in a rural district in Malawi is low and may engage to care late.

In the current finding, DPs were more likely to be tobacco smokers and debilitated patients from households with one room. The high probability of DP in tobacco smokers might plausibly be associated with the effect of smoking on Tb treatment outcome. A prospective cohort from Jordan reported that the risk of a poor Tb treatment outcome was much higher (70 %) in current smokers compared to never smokers [48]. Such a co-incidence of smoking and poor Tb treatment outcome might affect timely HIV care presentation. The potential of smoking to induce coughing and other symptoms consistent with tuberculosis may delay Tb diagnosis among smokers than non-smokers and this may prohibit to seek health care services as result of poor Tb prognosis that caused by delayed diagnosis [49]. Findings of our current study also support this in which the likelihood of bedridden patients to DP was higher than working patients.

For the above reasons, Tb experts declare “Clearing the smoke around the Tb/HIV Syndemic” [50]. In addition, the current finding may also call for designing and including strategies in the routine program to reduce tobacco among Tb/HIV co-infected patients [51]. In support of this, The Center for Disease Control (CDC) also calls for prompt action to incorporate anti-smoking strategies into Tb, HIV, and Tb-HIV care, and advise to apply the World Health Organization’s MPOWER [52] strategy for lessening tobacco use [51]. This is critical issue for Tb and HIV treatment and care in contributing not only for earlier presentation for HIV care but also for developing good prognosis after linking the care [50]. However, we also advised further study to explore the association between smoking and time to present for HIV care among the population.

Bedridden patients had eight times (AOR = 8.3, 95 % CI: 2.8–25.1) increased risk of DP than patients recorded as being in working status. These findings do not come as a surprise because patients who are bedridden have probably been exposed to more infections and have poorer health outcomes, a barrier that hinders early presentation for HIV care [50, 53]. It is thus plausible to suggest routine opportunistic infections and other diseases screening in patients with Tb or HIV in order to establish early and effective management strategies to reduce preventable mortalities from these conditions. In addition, HIV screening in general population, and home based HIV testing and linking to care should also be strengthened.

Tb/HIV patients from household with two or more rooms had 50 % lesser risk (AOR = 0.5, 95 % CI: 0.3–0.8) to DP than owning a single room. This demonstrated the role of adequate housing as an important enabler of effective care at steps of HIV care continuum. It is up on this intention that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) established the Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS (HOPWA) program and had a bold impact in the HIV Care Continuum Initiative [3]. The inadequacy in housing can lead to overcrowding that worsens Tb conditions in poor settings and this may deter HIV care use. This is supported by the current findings that significant proportion (61.3 %) of DP participants in the current study lived with more than five individuals in a single house. These factors have also been supported by several studies conducted across the globe [54–56]. This cues the need of revising intervention framework of Tb/HIV care that was focused on health sector alone. Efforts should be made to integrate and improve prevailing social determinants particularly housing in the management of HIV/Tb co-infection [29].

The study has the following limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, there were incomplete data and small sample size. This may have affected the precision of the estimates. Secondly, variables that could potentially have major contribution and confounding effect (e.g. HIV related stigma) were not assessed. Thirdly, due to inadequate data of desired variables, the prevalence of DP was not further described by delayed HIV testing and delayed ART initiation after early HIV testing. Fourthly, the proportion of DP is also not described by the timing of Tb diagnosis so that the effect of early or late Tb diagnosis would have been hypothesized. Fifthly, assessment of the effect of Tb treatment outcomes- default, lost to follow up, failure or cure- on time to present for HIV care is beyond the scope of the current study. Lastly, a gold standard measure of DP for resource limited countries is not yet established. As Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) group set definition of DP for the population of Europe [57], research groups in Africa should also set the ‘gold standard’ definition of DP for HIV care among general adult HIV positive population, HIV positive children, HIV positive mothers and Tb/HIV co-infected patients.

Conclusions

The findings of the current study have informed that three out of five Tb/HIV co-infected patients delayed for HIV care and delayed presenters were more likely to be tobacco smokers, bedridden patients and those who were from households with single bedroom. The existence of high DP among Tb/HIV co-infected cases needs actions to reduce the aforementioned risk factors. The findings of the current study have policy and practice implications and they call for effective management strategies for Tb/HIV co-infection including improved availability of early diagnosis and improved availability of ARVs. Such study should also be followed by further research to assess barriers of DP among other vulnerable groups such as children and mothers, and other key population.

Abbreviations

- AHR:

-

Adjusted hazard ratio

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immuno deficiency syndrome

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- DP:

-

Delayed presentation for HIV care

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IRIS:

-

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

- JUTH:

-

Jimma University Teaching Hospital

- MDR:

-

Multi drug resistance

- Tb:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Ford N, Johnston V, Lawn SD. Quantifying and addressing losses along the continuum of care for people living with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(2):17383.

UNAIDS. Global AIDS Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013.

Russell B, Alison G, Amy G, Katie P, Shubert V. HIV CARE CONTINUUM: The Connection Between Housing And Improved Outcomes Along The HIV Care Continuum. USA: CDC; 2013.

Gesesew HA, Fessehaye AT, Birtukan TA. Factors affecting late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in southwest Ethiopia: a case control study. Public Health Res. 2013;3(4):98–107.

Girardi E, Aloisi MS, Arici C, Pezzotti P, Serraino D, Balzano R, Vigevani G, Alberici F, Ursitti M, D'Alessandro M, et al. Delayed presentation and late testing for HIV: demographic and behavioral risk factors in a multicenter study in Italy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(4):951–9.

Castilla J, Sobrino P, De La Fuente L, Noguer I, Guerra L, Parras F. Late diagnosis of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: consequences for AIDS incidence. AIDS (London, England). 2002;16(14):1945–51.

Longo B, Pezzotti P, Boros S, Urciuoli R, Rezza G. Increasing proportion of late testers among AIDS cases in Italy, 1996–2002. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):834–41.

Delpierre C, Dray-Spira R, Cuzin L, Marchou B, Massip P, Lang T, Lert F. Correlates of late HIV diagnosis: implications for testing policy. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(5):312–7.

Santos J, Palacios R, Gutierrez M, Grana M, de la Torre J, Salgado F, Nuno E, Marquez M. HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: the Malaga Study. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(9):594–6.

Mayben JK, Kramer JR, Kallen MA, Franzini L, Lairson DR, Giordano TP. Predictors of delayed HIV diagnosis in a recently diagnosed cohort. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(3):195–204.

CDC. From the centers for disease control and prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Jama. 1993;269(6):729–30.

Krawczyk C, Funkhouser E, Kilby J, Kaslow R, Bey A, Vermund S. Factors associated with delayed initiation of HIV medical care among infected persons attending a southern HIV/AIDS clinic. South Med J. 2006;99(5):472–81.

Haskew J, Turner K, Rø G, Ho A, Kimanga D, Sharif S. Stage of HIV presentation at initial clinic visit following a community-based HIV testing campaign in rural Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–7.

Dennis AM, Napravnik S, Seña AC, Eron JJ. Late entry to HIV care among latinos compared with non-latinos in a Southeastern US Cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):480–7.

Abaynew Y, Deribew A, Deribe K. Factors associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in South Wollo ZoneEthiopia: a case–control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:8.

Paz Sobrino V, Santiago M, Rafael R, Pompeyo V, Jose´ Ignacio B, Jose´ Ramon B, et al. Impact of late presentation of HIV infection on short-, mid- and long-term mortality and causes of death in a multicenter national cohort: 2004-2013. J Infect. 2016;72(5):587–96.

Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800.

COHERE. Late presentation for HIV care across Europe: update from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) study, 2010 to 2013. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2015;20(47):e1001510.

Hachfeld A, Ledergerber B, Darling K, Weber R, Calmy A, Battegay M, Sugimoto K, Di Benedetto C, Fux CA, Tarr PE, et al. Reasons for late presentation to HIV care in Switzerland. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):20317.

Jeong SJ, Italiano C, Chaiwarith R, Ng OT, Vanar S, Jiamsakul A, Saphonn V, Nguyen KV, Kiertiburanakul S, Lee MP, et al. Late presentation into care of HIV disease and its associated factors in Asia: results of TAHOD. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016;32(3):255–61.

Mojumdar K, Vajpayee M, Chauhan NK, Mendiratta S. Late presenters to HIV care and treatment, identification of associated risk factors in HIV-1 infected Indian population. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:416.

Geng EH, Hunt PW, Diero LO, Kimaiyo S, Somi GR, Okong P, Bangsberg DR, Bwana MB, Cohen CR, Otieno JA, et al. Trends in the clinical characteristics of HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania between 2002 and 2009. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:16.

Mulissa Z, Jerene D, Lindtjorn B. Patients present earlier and survival has improved, but Pre-ART attrition is high in a six-year HIV cohort data from Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13268.

Abebe N, Alemu K, Asfaw T, Abajobir AA. Survival status of hiv positive adults on antiretroviral treatment in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17:88.

Kigozi IM, Dobkin LM, Geng EH, Emenyonu NI, Bangsberg DR, Hahn JA. Late-disease stage at presentation to an HIV clinic in the era of free antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2009:52.

Nyika H, Mugurungi O, Shambira G, Gombe NT, Bangure D, Mungati M, Tshimanga M. Factors associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Harare City, Zimbabwe, 2015. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–7.

Gelaw YA, Senbete GH, Adane AA, Alene KA. Determinants of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in Southern Tigray Zone, Northern Ethiopia: An institution based case–control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12:40.

Gesesew HA, Lillian M, Paul W, Kifle WH, Garuma TF. Factors associated with discontinuation of anti-retroviral therapy among adults living with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(2):27–36.

Gesesew H, Tsehaineh B, Massa D, Tesfay A, Kahsay H, Mwanri L. The role of social determinants on tuberculosis/HIV co-infection mortality in southwest Ethiopia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Research Notes. 2016;9:89.

CDC. Prevention and Treatment of Tuberculosis Among Patients Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Principles of Therapy and Revised Recommendations. MMWR. 1998;47(RR20):1–51.

Toossi Z. Virological and immunological impact of tuberculosis on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(8):1146–55.

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2015. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

CSA. Population and Housing Census Report: Ethiopia. Addis Abba: Central Statistical Agency; 2007.

CSA, ICF. Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2011. Addis Ababa and Calverton: Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International; 2012. p. 17–27.

Becky LG, Joseph WH, Paula B. Home testing and counselling with linkage to care. The Lancet HIV. 2016;3(6):e244–e246.

Yared M, Sanders R, Tibebu S, Emmart P. Equity and Access to ART in Ethiopia. USA: USAID; 2010.

Assefa Y, Alebachew A, Lera M, Lynen L, Wouters E, Van Damme W. Scaling up antiretroviral treatment and improving patient retention in care: lessons from Ethiopia, 2005–2013. Glob Health. 2014;10:43.

Maponga BA, Chirundu D, Gombe NT, Tshimanga M, Bangure D, Takundwa L. Delayed initiation of anti-retroviral therapy in TB/HIV co-infected patients, Sanyati District, Zimbabwe, 2011–2012. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21:28.

Abay SM, Deribe K, Reda AA, Biadgilign S, Datiko D, Assefa T, Todd M, Deribew A. The effect of early initiation of antiretroviral therapy in TB/HIV-coinfected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(6):560–70.

FDRE, MOH. Guidelines On Programmatic Management Of Drug Resistant Tuberculosis In Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Minstry of Health; 2012.

Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. Jama. 2009;301(22):2380–2.

Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57.

Julio SGM, Robert H, Evan W, Thomas K, Mark T, Adrian RL, Richard H. The case for expanding access to highly active antiretroviral therapy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. Lancet. 2006;368(9534):531–6.

Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, de Wolf F, Phillips AN, Harris R, Funk MJ, Geskus RB, Gill J, Dabis F, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1352–63.

Piggott DA, Karakousis PC. Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in the setting of TB treatment. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:103917.

Torok ME, Yen NT, Chau TT, Mai NT, Phu NH, Mai PP, Dung NT, Chau NV, Bang ND, Tien NA, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)--associated tuberculous meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(11):1374–83.

Zachariah R, Harries AD, Manzi M, Gomani P, Teck R, Phillips M, Firmenich P. Acceptance of anti-retroviral therapy among patients infected with HIV and tuberculosis in rural Malawi is low and associated with cost of transport. PLoS One. 2006;1(1):e121.

Gegia M, Magee MJ, Kempker RR, Kalandadze I, Chakhaia T, Golub JE, Blumberg HM. Tobacco smoking and tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a prospective cohort study in Georgia. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(6):390–9.

Rabin A, Kuchukhidze G, Sanikidze E, Kempker R, Blumberg H. Prescribed and self-medication use increase delays in diagnosis of tuberculosis in the country of Georgia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(2):214–20.

Jackson-Morris A, Fujiwara PI, Pevzner E. Clearing the smoke around the TB-HIV syndemic: smoking as a critical issue for TB and HIV treatment and care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(9):1003–6.

CDC. TB, HIV, and Smoking: A Perfect Storm. 2015. Available at [http://www.cdc.gov/globalaids/success-stories/perfectstorm.html]. Accessed 13 May 2016.

WHO. MPOWER: Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI). 2012. Available at [http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/]. Accessed 13 May 2016.

Addis Alene K, Nega A, Wasie Taye B. Incidence and predictors of tuberculosis among adult people living with human immunodeficiency virus at the University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:292.

Boccia D, Hargreaves J, Ayles H, Fielding K, Simwinga M, Godfrey-Faussett P. Tuberculosis infection in Zambia: the association with relative wealth. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(6):1004–11.

Baker M, Das D, Venugopal K, Howden-Chapman P. Tuberculosis associated with household crowding in a developed country. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(8):715–21.

Cordoba-Dona JA, Novalbos-Ruiz JP, Suarez-Farfante J, Anderica-Frias G, Escolar-Pujolar A. Social inequalities in HIV-TB and non-HIV-TB patients in two urban areas in southern Spain: multilevel analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(3):342–7.

Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, Monforte A, Brockmeyer N, Casabona J, Castagna A, Costagliola D, Dabis F, Wit SD, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: results from the collaboration of observational HIV epidemiological research Europe study (COHERE). PLoS Med. 2013;10(9):e1001510.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to JUTH and data collectors. Jimma University granted the study.

Funding

This research was funded by Jimma University and was received by Hailay Gesesew. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its additional SPSS file.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed in designing of the study, data collection, data analysis, drafting and critically reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

HG is lecturer of Epidemiology in College of Health Sciences at Jimma University and a PhD student in the Discipline of Public Health in Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University. BT is lecturer of Biostatistics in the College of Health Sciences at Jimma University and a master’s student in School of Statistics and Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Alberta University. DM is lecturer of Epidemiology in the College of Health Sciences at Jimma University, and AT is lecturer of reproductive health in the College of Health Sciences, Jimma University. HK is a pharmacist in ART clinic of Filtu hospital in Somali, Ethiopia. LM is a senior lecturer and course coordinator of Master of Health and International Development in the Discipline of Public Health in Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University. All authors are currently staff members in their respective departments.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent

Waiver of the consent was obtained from the office of institutional ethical review board (IRB) of College of Health Sciences, Jimma University, and the reference number was RPGC/558/2012. The data access permission was obtained from JUTH board. We extracted an anonymised data from the record and no participant was taken part in the study. The data and collected information was kept and locked in a filing cabinet with the key only accessible to principal investigator (PI) and the computer files were protected with passwords that only the PI knows.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Multilingual abstracts in the six official working languages of the United Nations. (PDF 763 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gesesew, H., Tsehaineh, B., Massa, D. et al. The prevalence and associated factors for delayed presentation for HIV care among tuberculosis/HIV co-infected patients in Southwest Ethiopia: a retrospective observational cohort. Infect Dis Poverty 5, 96 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-016-0193-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-016-0193-y