Abstract

In this study, we conducted a survey of newly discovered populations of tuco-tuco (subterranean rodents of the genus Ctenomys) in the Entre Ríos province, in an area characterized by its unexplored nature and its climatic and biogeographic complexity within Argentina, which includes two National Parks. We characterize the nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome-b gene, revealing the presence of seven novel haplotypes within Ctenomys rionegrensis, a species known to inhabit both sides of the Uruguay River. Through Bayesian analyses, we estimated the divergence times of the oldest lineages of C. rionegrensis, as well as those of the haplotypes located east of the Uruguay River, dating back approximately 630,000 years before present (ybp) and 526,000 ybp, respectively. These estimates correspond with significant paleogeographic events in the region. Our findings may raise questions regarding the taxonomic classification of the species and suggest potential modifications to its current endangered status as designated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Consequently, this research provides valuable insights that may inform future revisions of the species' conservation status and guide the development of informed management strategies/policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The tuco-tucos (also known as tucu-tucus, tunducos, and ocultos, among other names) are subterranean rodents native to South America and belong to the genus Ctenomys Blainville 1826. Currently, there are 67 described species within this genus, and the taxonomy remains a subject of ongoing research, characterized by controversy and dynamism (e.g., [28,29,30,31], in the last year). Many regions inhabited by tuco-tucos lack comprehensive species identification, with more than 40% of species categorized as Data Deficient (DD) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2015), and approximately 75% considered endangered [15].

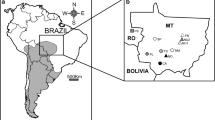

The Entre Ríos province in Argentina (Fig. 1a) encompasses three distinct ecoregions: the Espinal in the north, the Pampa in the center, and the Delta and Islands of the Paraná River in the south, bordering Santa Fe and Buenos Aires provinces [11]. This region is characterized by a complex mosaic of terrestrial, riparian, and aquatic habitats, harboring endemic species and biological communities unique to the area [1]. The intricate patterns of biodiversity in Entre Ríos are likely shaped by past geomorphological events, ecological factors, and the current hydrological connectivity of waterways with surrounding biogeographic regions [2]. Accurate species identification and phylogeographic studies can provide insights into the paleogeographic and historical processes that have influenced the region, facilitating reassessment of conservation statuses. Because tuco-tucos are distributed in patches determined by soil hardness and particle size suitable for underground activity (e.g., [3], they are closely linked to the substrate and are excellent indicators for this purpose (e.g., [21]). It is possible to find different species occupying the same patches of environments [22].

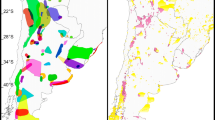

Summary of studied populations and haplotypes of C. rionegrensis. a: Map of the studied populations. Underline: provided by this study. Dashed area: suggested distribution for the species [14], IUCN),b: Phylogenetic relationship of C. rionegrensis haplotypes. The Genbank accession numbers and the locality of precedence are indicated (except for the one shared between the towns of Abrogal, Guarida and Nuevo Berlín (1, 3 and 8)). The numbers in the nodes are the posterior probabilities greater than 0.5; c: Red haplotypes of C. rionegrensis. The area of the circle is proportional to its frequency. The crossed lines on the connecting lines represent changes between haplotypes. The number next to each haplotype corresponds to the populations on the map in part a, and the letters correspond to the haplotypes in the tree in part b

The about 80,000 km2 of the Entre Ríos province, has been practically ignored concerning the tuco-tucos’ species. While two species have been reported in this region, their geographic distributions remain poorly documented. Ctenomys pearsoni Lessa and Langguth, 1983, primarily found in Uruguay [4, 10], has been reported in Entre Ríos [27] referred as C. torquatus, [12]. Its conservation status was initially categorized as Near Threatened by the IUCN but later revised to Least Concern based on updated distribution data [15]. Ctenomys rionegrensis Langguth and Abella, 1970 also was reported for Entre Ríos in its original description, and previously mentioned by Reig et al. [27] as Ctenomys minutus. Later, D'Elía et al. [17] corroborated its presence in Paraná and Ibicuy, and Caraballo et al. [14] reported it in Pre-Delta National Park (PDNP) (Fig. 1, a). Due to its restricted range and habitat threats, this species is currently listed as Endangered by the IUCN [5, 15]. Additionally, the presence of neighboring species such as Ctenomys torquatus Lichtenstein, 1830, and Ctenomys dorbignyi Contreras and Contreras, 1984, cannot be discounted in Entre Ríos province.

We assessed five new populations of tuco-tucos of Entre Ríos province by characterizing cytochrome-b sequences to test the hypothesis of the presence of one of the two species reported for the region. Once the species was identified, we conducted phylogeographic analyses including neighboring conspecific populations to draw biogeographical conclusions.

Materials and methods

We took tissue samples preserved in 95% ethanol from Ctenomys spp. specimens collected at five locations within Entre Ríos, Argentina, and archived at the Centro de Bioinvestigaciones (CeBio, Universidad Nacional del Noroeste de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Pergamino): El Federico Estate, Provincial Route 38, 10km west of Ubajay (31°46'33.8" S, 58°22'45.7" W) (n=3, ER1-ER3); National Route 14 (Km 175) near Paraje Mabragaña (32°04'26.8" S, 58°15'13.3" W) (n=3, ER4-ER6); and three trapping stations within El Palmar National Park (EPNP), namely EPNP North1 (30°59'59.9'' S, 57°59'59.92'' W) (n=2, ER7-ER8), EPNP North2 (30°59'59.9'' S, 57°59'59.9'' W) (n=1, ER9), and EPNP South (30°59'59.9'' S, 57°59'59.9'' W) (n=3, ER10-ER12) (Fig. 1a).

DNA extraction followed a standardized protocol [23], with PCR amplification of the cytochrome-b gene (cyt-b) using primers NTUCO05C (5'-TAACCAAGACTAATGATAYGAAAAACC-3') and TUCO14A [32] in a final volume of 20µl, containing 10µl of GoTaqHotStart Kit (Promega), 3µl of each primer 10mM, and 4µl of 1:100 dilution of DNA extraction. The PCR cycling was performed in a Thermo thermal cycler (PxEthermalcycler). The cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C, annealing at 45°C, and extension at 72°C (30 sec. each step), with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were purified and sequenced bi-directionally by Macrogen (http://www.macrogen.com)

To estimate the phylogeny of C. rionegrensis, we included Genbank sequences: all available sequences of C. rionegrensis, all cyt-b and available species of the phylogenetic group (mendocinus) to which this species belongs [24], and representatives of other Ctenomys species and outgroups (Supplementary materials, Table SI 1a, b). Phylogenetic inference was performed using BEAST 2.5 [9] with a MCMC chain length of 10,000,000 generations, discarding the initial 10% as burn-in. Sequences were partitioned according to Caraballo and Rossi [13]. We used HKY+Y+G as the fittest substitution model for 1st+2nd and TIM2+G for 3rd, both selected by BIC score in jModelTest [25].

The spatio temporal dynamics was reconstructed through continuous diffusion analysis of C. rionegrensis using the GEO_SPHERE package [8] in BEAST. Sampling locations and geographic coordinates are provided in Supplementary Table SI 2. To minimize conflicts arising from using different sequences from identical sampling sites, random "jittering" was applied. We employed a strict clock with secondary calibration based on rates inferred from a previous fossil multi-calibrated analysis [16], with a mean rate of 0.0202 substitutions/site/My, setting upper and lower bounds to 0.0198-0.0206 s/s/My. Substitution models were selected for 1st+2nd and for 3rd codon positions, respectively. Two independent runs for 30,000,000 MCMC generations, sampling every 5,000 generations, with a burn-in of 25%, were performed. Convergence diagnostics were carried out using Tracer 1.6.0 [26], log files were combined using LogCombiner 2.4.4, and a Maximum Clade Credibility (MCC) tree was annotated with TreeAnnotator 2.4.4. The resulting Maximum Clade Credibility (MCC) tree was converted into a keyhole markup language (KML) file using SPREAD 1.0.6 [6], available for interactive visualization in Supplementary materials (Figure SI 1).

From all C. rionegrensis sequences (n=27), we calculated haplotypic (Hd) and nucleotide (π) diversity, mean number of paired differences (k), and number of polymorphic sites (S) using Arlequin software [18] (see Table 1). Additionally, Tajima's D and Fu's Fs neutrality tests were conducted, along with exact tests to evaluate genetic differentiation between pairs of populations based on haplotype frequencies, and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) to assess genetic variation structuring and the potential effect of the Uruguay River as a geographical barrier (see Table 1).

Results and discussion

We identified seven novel haplotypes (1071bp), with one each in Ubajay and Paraje Mabragaña, two in EPNPNorth1, one in EPNPNorth2, and two in EPNPSouth, exhibiting differences in 17 transitions. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that the evaluated populations belong to C. rionegrensis, forming a monophyletic clade with previously reported sequences of the same species, supported by high Bayesian posterior probability values (Fig. 1,b) (Supplementary materials, Figure SI 2a, b).

Approximately half of the populations possessed unique haplotypes among the 16 populations and 27 haplotypes of C. rionegrensis analyzed (Fig. 1c). Notably, eight haplotypes were polymorphic: Abrojal, Chaparrei, Arrayanes, Mafalda, La Tabaré, PDNP, EPNPNorth1, and EPNPSouth. Haplotypes west of the Uruguay River (hereafter referred to as Argentinian) exhibited higher genetic variation (k=8.51, S=40) than those to the east (hereafter Uruguayan, k=2.92, S=22) (Table 1) and were paraphyletic to the latter (Fig. 1b), occupying a broader geographic distribution. The paraphyly of Argentinian haplotypes, along with their higher nucleotide and haplotypic diversity indexes, suggests that current Uruguayan populations diverged from an ancestor originating in Argentina, reflecting a deeper historical connection with larger population sizes (either current or past) in that country [20]. Moreover, the prevalence of fixed and unique haplotypes per population underscores the pronounced influence of genetic drift, indicative of small and isolated populations [32], a characteristic trait of the genus.

The genetic differentiation tests between pairs of populations, measured as FST, was significant in most cases (Supplementary materials, Table SI 3). AMOVA revealed that differences between groups (Uruguayan vs. Argentinian haplotypes) accounted for 55.76% of the variance. Approximately 11.0% of the variance was attributed to variation within populations, with slightly over 30% (33.25%) attributed to differences between populations within groups. This outcome indicates that the Uruguay River acts as a significant barrier to gene flow.

Tajima's tests were not significant for polymorphic populations or within each group (Uruguayan vs. Argentinian haplotypes). However, Uruguayan haplotypes exhibited negative and marginally significant D values (D=-1.43, p=0.06), while Fu's test yielded significant results (Fs=-6.28, p=0.01), suggesting a recent population expansion, consistent with previous findings [32]. Although the Argentinian haplotypes displayed non-significant Tajima and Fu values (D=-1.23, p=0.11,Fs=-1.03, p=0.30), the absence of an expansion signal may be attributed to the limited number of samples evaluated. Furthermore, Uruguayan haplotypes exhibited an average divergence (p-distance) of 0.003, whereas the six Argentinian haplotypes displayed 0.012.

Divergence time estimations by BEAST suggest that current C. rionegrensis lineages originated at approximately 630,000 ybp (95% highest posterior density: 923,000-360,000). The colonization of Uruguay likely occurred between the origin of this lineage (526,000 ybp, 95% HPD: 770,000-318,000 ybp) and their most recent common ancestor (136,000 ybp, 95% HPD: 230,000-60,000 ybp), aligning with climatic changes during the Middle and Late Pleistocene [19]. Notably, the Great Patagonian Glaciation, occurring between 0.98 and 0.5 Myr, marked a colder and drier climate, with an absolute thermal minimum at 0.6 Myr, evidenced by a consistent decline in both plant and faunal content in the stratigraphic record [7]. During this period, favorable conditions such as the expansion of savannas and steppes facilitated the differentiation and expansion of C. rionegrensis, eventually reaching Uruguayan territory. Subsequently, as conditions became more humid, increased flow in the Uruguay River due to humid and warm conditions isolated populations to the east of the river, leading to progressive differentiation up to the present day. Interestingly, this timeframe corresponds to the migration of another tuco-tuco species, C. pearsoni, crossing the Uruguay River from Uruguay to the Entre Ríos province [13].

Our findings add novel points of occurence to the species distribution (Fig. 1a), describing novel populations and highlighting pronounced differentiation among them. The fixation of several exclusive haplotypes suggests a lack of connection between populations. In extreme cases, Uruguayan populations have been isolated for millennia, evolving as independent units. Consequently, we speculate on the possibility of assigning species status to the forms on both sides of the Uruguay River.

Our results provide insights into the taxonomy of C. rionegrensis, potentially informing a reassessment of the conservation status of the species and the development of conservation policies, including those for the protected area El Palmar National Park (EPNP). However, to propose efficient conservation management strategies and to understand the distribution patterns of biodiversity and its regional complexities, further evaluation of tuco-tuco populations in Entre Ríos is imperative.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Apodaca MJ, katinas L, Guerrero EL. Hidden areas of endemism: Small units in the South-eastern Neotropics. System. Biodivers. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2019.1646833.

Arana MD, Natale ES, Ferretti NE, Romano GM, Oggero AJ, Martínez G, Posadas PE, Morrone JJ. Esquema biogeográfico de la República Argentina. Fundación Miguel Lillo. Tucumán, Argentina, 2021.

Austrich A, Kittlein MJ, Mora MS, Mapelli F. Potential distribution models from two highly endemic species of subterranean rodents of Argentina: which environmental variables have better performance in highly specialized species? Mamm Biol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42991-021-00150-1.

Bidau CJ. Familia Ctenomyidae Lesson. In: Patton JL, Pardiñas UF, D’Elía G, editors. Mammals of South America, Volume 2: rodents. University of Chicago Press: Chicago; 2015. p. 818–77.

Bidau CJ. Ctenomys rionegrensis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 2018: e.T136635A22193418. 2018; https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-.RLTS.T136635A22193418.en.

Bielejec F, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Lemey P. SPREAD: spatial phylogenetic reconstruction of evolutionary dynamics. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2910–2.

Bossi J, Ortiz A, Perea D. Pliocene to middle Pleistocene in Uruguay: a model of climate evolution. Quat Int. 2009;210:37–43.

Bouckaert R. Phylogeography by diffusion on a sphere: whole world phylogeography. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2406. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2406.

Bouckaert RR, Vaughan TG, Barido-sottani J, Duchêne S, Fourment M, Gavryushkina A. BEAST 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006650.

Boullosa N. Avances en el estudio de los tucu-tucus (Ctenomys, Ctenomydae) en Uruguay: filogeografía y transcriptómica. 2019. Tesis de maestría. Universidad de la República (Uruguay). Facultad de Ciencias-PEDECIBA.

Brown A, Pacheco S. Propuesta de actualización del mapa ecorregional de la Argentina. In: Brown A, Martínez Ortiz U, Acerbi M, Corcuera J, editors. La Situación Ambiental Argentina 2005. Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina: Buenos Aires; 2006. p. 28–31.

Caraballo DA, Tomasco IH, Campo DH, Rossi MS. Phylogenetic relationships between tuco-tucos (Ctenomys, Rodentia) of the corrientes group and the C. pearsoni complex. Mastozoologia Neotropical. 2016;23:39–49.

Caraballo DA, Rossi MS. Spatial and temporal divergence of the torquatus species group of the subterranean rodent Ctenomys. Contrib Zool. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1163/18759866-08701002.

Caraballo DA, López SL, Carmarán AA, Rossi MS. Conservation status, protected area coverage of Ctenomys (Rodentia, Ctenomyidae) species and molecular identification of a population in a national park. Mamm Biol. 2020;100:33–47.

Caraballo DA, López SL, Botero-cañola S, Gardner SL. Filling the gap in distribution ranges and conservation status in Ctenomys (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae). J Mammal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyac099.

Carnovale CS, Fernández GP, Merino ML, Mora MS. Redefining the distributional boundaries and phylogenetic relationships for ctenomyids from central Argentina. Front Genet. 2021;12:698134. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.698134.

D’elía G, Lessa EP, Cook JA. Molecular phylogeny of Tucos-Tucos genus Ctenomys (Rodentia: Octodontidae) Evaluation of the mendocinus species group and the evolution of assimetric sperm. J Mamm Evol. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020586229342.

Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x.

Ferrero BS, Noriega JI. Nuevos registros de mamíferos del Pleistoceno Tardío (MIS 5) en el sur de la Mesopotamia argentina. Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina. 2023;23(1):204–30.

Hartl DL, Clark AG. Principles of population genetics (4th ed.). Oxford University Press; 2007.

Lopes CM, Ximenes SSF, Gava A, Freitas TRO. The role of chromosomal rearrangements and geographical barriers in the divergence of lineages in a South American subterranean rodent (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae: Ctenomys minutus). Heredity. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2013.49.

Mapelli F, Mora MS, Lancia J, Gomez Fernandez M, Mirol P, Kittlein MJ. Evolution and phylogenetic relationships in subterranean rodents of Ctenomys mendocinus species complex: effects of Late Quaternary landscape changes of Central Argentina. Mamm Biol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2017.08.002.

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky H.F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988; https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/16.3.1215.

Parada A, D’elía G, Bidau CJ, Lessa EP. Species groups and the evolutionary diversification of tuco-tucos genus Ctenomys (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae). J Mammal. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1644/10-MAMM-A-121.1.

Posada D. JModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msn083.

Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Xie D, Drummond AJ. Tracer v1.6, 2014. Available from http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer.

Reig OA, Contreras JR, Piantanida MJ. Contribución a la elucidación de la sistemática de las entidades del género Ctenomys (Rodentia, Octodontidae). Relaciones de parentesco entre muestras de ocho poblaciones de tuco-tucos inferidas del estudio estadístico de variables del fenotipo y su correlación con las características del genotipo. Contrib Cien Ser Zool. 1966;2:297–352.

Sanchez T, Tomasco IH, Diaz M, Barquez R. Review of three neglected species of Ctenomys (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae) from Argentina. J Mammal. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyad001.

Tammone M, Voglino D, Cuellar Soto E, Pardiñas U. Resolving the taxonomic status of Ctenomys paramilloensis (Rodentia, Ctenomyidae), an Andean nominal form from Mendoza Province Argentina. Mammalia. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1515/mammalia-2023-0133.

Teta P, Jayat P, Alvarado-larios R, Ojeda A, Cuello P, D’elía G. An appraisal of the species richness of the Ctenomys mendocinus species group (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae), with the description of two new species from the Andean slopes of west-central Argentina. Vertebr Zool. 2023;73:474. https://doi.org/10.3897/vz.73.e101065.

Verzi D, De Santi N, Olivares A, Morgan C, Basso N, Brook F. A new species of the highly polytypic South American rodent Ctenomys increases the diversity of the magellanicus clade. Vertebr Zool. 2023;73:289–312. https://doi.org/10.3897/vz.73.e96656.

Wlasiuk G, Garza JC, Lessa EP. Genetic and geographic differentiation in the Rio Negro tuco-tuco (Ctenomys rionegrensis): inferring the roles of migration and drift from multiple genetic markers. Evolution. 2003;57:913–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-820.2003.tb00302.x.

Acknowledgements

We thank to the Universidad de la República, the UNNOBA for funding (SIB 0600/2019) (SIB 2093/2022) and to the Iguazú Jungle company for financing field campaigns. Especially Alejandro Arrabal, Ignacio Acha and Ariel Soria for the support received. Finally, we really thank Ulyses F. J. Pardiñas and one anonymous reviewer for their valuable contributions in improving our manuscript, and to Monica Santilli (UNNOBA) for her help with the English language.

Funding

SIB 0600/2019; 2093/2022, UNNOBA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IHT and GPF designed the study and participated in all stages of the study, VDZP made the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IHT, GPF, MEMA, AC and MLM performed the field work. DC and CSC contributed to obtain the data and perform the spatiotemporal analysis. DC also collaborated by financing the sequencing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in accordance with Argentinian laws.

Consent for publication

All authors agree with the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zelada Perrone, V.D., Tomasco, I.H., Mac Allister, M.E. et al. Five new unexpected populations of endangered tuco-tuco Ctenomys rionegrensis (Rodentia, Ctenomyidae) help understanding its distribution and historical biogeography. Rev. Chil. de Hist. Nat. 97, 4 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40693-024-00127-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40693-024-00127-7