Abstract

Background

Individuals with multiple islet autoantibodies are at increased risk for clinical type 1 diabetes and may proceed gradually from stage to stage complicating the recruitment to secondary prevention studies. We evaluated multiple islet autoantibody positive subjects before randomisation for a clinical trial 1 month apart for beta-cell function, glucose metabolism and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). We hypothesized that the number and type of islet autoantibodies in combination with different measures of glucose metabolism including fasting glucose, HbA1c, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), intra venous glucose tolerance test (IvGTT) and CGM allows for more precise staging of autoimmune type 1 diabetes than the number of islet autoantibodies alone.

Methods

Subjects (n = 57) at 2–50 years of age, positive for two or more islet autoantibodies were assessed by fasting plasma insulin, glucose, HbA1c as well as First Phase Insulin Response (FPIR) in IvGTT, followed 1 month later by OGTT, and 1 week of CGM (n = 24).

Results

Autoantibodies against GAD65 (GADA; n = 52), ZnT8 (ZnT8A; n = 40), IA-2 (IA-2A; n = 38) and insulin (IAA; n = 28) were present in 9 different combinations of 2–4 autoantibodies. Fasting glucose and HbA1c did not differ between the two visits. The estimate of the linear relationship between log2-transformed FPIR as the outcome and log2-transformed area under the OGTT glucose curve (AUC) as the predictor, adjusting for age and sex was − 1.88 (− 2.71, − 1.05) p = 3.49 × 10–5. The direction of the estimates for all glucose metabolism measures was positive except for FPIR, which was negative. FPIR was associated with higher blood glucose. Both the median and the spread of the CGM glucose data were significantly associated with higher glucose values based on OGTT, higher HbA1c, and lower FPIR. There was no association between glucose metabolism, autoantibody number and type except that there was an indication that the presence of at least one of ZnT8(Q/R/W) A was associated with a lower log2-transformed FPIR (− 0.80 (− 1.58, − 0.02), p = 0.046).

Conclusions

The sole use of two or more islet autoantibodies as inclusion criterion for Stage 1 diabetes in prevention trials is unsatisfactory. Staging type 1 diabetes needs to take the heterogeneity in beta-cell function and glucose metabolism into account.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02605148, November 16, 2015

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The clinical onset of autoimmune type 1 diabetes is preceded by a prodrome of immune-associated dysfunction of the pancreatic islet beta-cells resulting in an eventual failure to produce sufficient amounts of insulin to maintain normal blood glucose. The aetiology of the disease is thought to include environmental factors such as virus [1, 2] that would trigger islet autoimmunity marked by the appearance of either autoantibodies against insulin (IAA) or GAD65 (GADA) as the first appearing autoantibody [3,4,5]. In about 60% of children who developed either IAA first or GADA first, a second autoantibody appeared within 1 year [6]. Children, as well as adults, with two or more islet autoantibodies proceed to develop diabetes but it may take up to 20 years before the clinical onset [7]. Hence, the sub-clinical autoimmune process resulting in the destruction and dysfunction of beta-cells begins months (in very young children) or years before the appearance of the classical clinical symptoms of type 1 diabetes and is reflected in a decreased first phase insulin response (FPIR) [[8] related to the number of islet autoantibodies and genetic factors other than HLA [9, 10]]. At the onset of clinical symptoms, only a small fraction of the functional beta-cell mass is thought to be left.

The gradual loss of pancreatic islet beta-cell function is associated with both a cellular and a marked humoral immune response reflected by autoantibodies against several beta-cell autoantigens. At the clinical onset, about 95% of the patients have one or several autoantibodies against islet antigen-2 (IA-2A) and ZnT8 transporter (ZnT8A) in addition to GADA and IAA [11, 12]. These autoantibodies not only predict the clinical onset of type 1 diabetes [7], but may also be biomarkers of the pathogenic process leading to clinical diagnosis. The autoantibody biomarkers are therefore used to screen subjects at increased genetic risk of type 1 diabetes, such as first-degree relatives [13]. In a previous analysis, we showed that single autoantibody positive subjects had normal beta-cell function. Compared to subjects with two autoantibodies, subjects positive for three or more autoantibodies had a lower FPIR [8, 14]. This observation supports the view that the beta-cell function had deteriorated when the subjects progressed from positivity for two to having three autoantibodies. It is also consistent with the observation that children 4–9 years of age with GADA and at least one more autoantibody, had variable glucose metabolism [15].

In the present work, we wanted to test the hypothesis that the number and type of islet autoantibodies in combination with five different measures of glucose metabolism including fasting glucose, HbA1c, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), intra venous glucose tolerance test (IvGTT) and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) allows for more precise staging of autoimmune type 1 diabetes than the number of islet autoantibodies alone. Specifically, the aim was to determine whether in subjects positive for at least two islet autoantibodies and to be randomized in a clinical intervention trial NCT02605148. (1) the number and (2) the types of autoantibodies were associated with any of the baseline measures of beta-cell function and glucose metabolism.

Methods

Study population

The study included 57 research subjects who agreed to participate in a first visit with an IvGTT and 1 month later in a second visit with an OGTT. The subjects were relatives to research subjects who participated in longitudinal studies because they were born with increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes including the TEDDY study [16, 17]. There were 15/57 (26%) who had a father (n = 6), mother (n = 3), sibling (n = 3) or a child (n = 4) with type 1 diabetes. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Supplementary Table 1, Additional file.

The characteristics of the n = 57 subjects recruited from Sweden and Finland are summarized in Table 1. The median (interquartile range (IQR)) age was 11.0 years (8.0, 16.0), the country-specific median (IQR) age was 13.0 years (10.0, 16.0) for subjects in Sweden and 8.0 years (3.3, 13.0) for subjects in Finland. Of the 57 subjects, 30 (52.6%) were female, and all subjects were within the normal range of height, weight and HbA1c (Table 1).

In addition to demographic information, we have data on autoantibodies at both visit 1 and 2, fasting glucose, HbA1c, IvGTT (visit 1), OGTT (visit 2), and CGM for 24/57 subjects for 1 week after visit 2. Thus, for most analyses the sample size was n = 57, and for analyses involving CGM data the sample size was n = 24.

Blood samples and analyses

Blood samples were analyzed for plasma glucose, serum insulin and C-peptide, HbA1c and autoantibodies. The analyses were performed at local clinical chemistry laboratories as described earlier [14]. In an attempt to harmonize assays for serum insulin, samples were in addition analyzed by using ELISA in the Diabetes Research Laboratory, Oulu, Finland. The serum insulin assays in Oulu and in Malmö were correlated (r2 = 0.985) and all measurements in Oulu were normalized to Malmö levels in mIE/L.

Swedish samples for GADA, IA-2A, IAA and ZnT8A were analyzed in Malmö, Sweden and in Oulu, Finland for the Finnish samples except ZnT8(W,R) A which were analyzed in Helsinki, Finland. All three laboratories participate in the Islet Autoantibody Standardization Program (IASP) [18]. The GADA assay was 64% sensitive and 94% specific for the samples analyzed in Malmö and 60% sensitive and 97.8% specific for those analyzed in the DIPP laboratory in Oulu. The IA-2A assay was 62% sensitive and 100% specific for the samples analyzed in Malmö and 76% sensitive and 100% specific in Oulu. The IAA assay was 18% sensitive and 96.7% specific for the samples analyzed in Malmö and 40% sensitive and 96.7% specific in Oulu. ZnT8(R/W/Q)A (three variants at position 325) were analyzed in Malmö while the laboratory in Helsinki determined ZnT8A simultaneously for both the ZnT8R and W variants. The IASP results were 66% sensitive and 100% specific for ZnT8(RWQ)A in Malmö and 74% sensitive and 100% specific for ZnT8(R,W)A in Helsinki.

Glucose metabolism measures

Fasting and stimulated C-peptide and insulin levels were measured at both visits 1 and 2. HbA1c was analyzed using a spectrophotometric assay (Capillary 3 Tera; Sebia, Paris, France). The reference values for samples analyzed for HbA1c were 27–42 mmol/mol in Malmö and 20–42 mmol/L in Oulu and Turku. The reference values in Malmö were in subjects 1 months – 18 years of age: p-glucose 1 month – 18 yrs.: 3.3–5.6 mmol/L and above 18 yrs.: 4.2–6.3 mmol/L, s-insulin < 25 mIE/ L mIE/L, s-C-peptide: 0.37–1.5 nmol/ L. The corresponding reference values were in Oulu: p-glucose 4.2–6.0 mmol/L, s-insulin 5–20 mU/L mIE/L, s-C-peptide: > 0.9 nmol/ L, and in Turku: p-glucose 4–6 mmol/L, s-insulin 2.6–25 mU/L mIE/L, s-C-peptide 0.37–1.47 nmol/L. All sample reference ranges apply to fasting condition.

Statistical methods

The autoantibody data was coded as a binary variable for each autoantibody (GADA, IAA, IA-2A, ZnT8(W/R/Q)A). We also considered the number of autoantibodies, where GADA, IAA and IA-2A each counted as 1 and any of ZnT8(W/R/Q)A counted as 1, thus the autoantibody count ranged from 2 to 4 for all subjects. The autoantibody status combinations were grouped into 4 categories, based on three most common combinations forming a category each, and the remaining combinations forming the fourth group. Fasting glucose and HbA1c values were evaluated using non-parametric paired Wilcoxons rank test to compare the distributions of fasting glucose and HbA1c between visits 1 and 2. The glucose values from an OGTT were used as individual values at a given time point (− 10 to 120 min), as well as summarized as the area under the OGTT curve (AUC). The FPIR values estimated from IvGTT were right-skewed and were log2-transformed. We performed a descriptive analysis evaluating the integrity of the data and visualizing the univariate and bivariate relationships between the different measures of glucose, as well as between glucose and autoantibody count and type, as well as FPIR and HbA1c.

Linear regression, adjusting for age and sex, was used to evaluate whether there was an association between each of 10 glucose metabolism measures (as the outcome) and autoantibody (1) status, (2) count, or (3) type (as predictors). The ten measures of glucose metabolism we considered were (A) OGTT 2 h glucose, (B) log2-transformed OGTT glucose AUC, (C) log2-transformed OGTT C-peptide AUC, (D) log2-transformed OGTT insulin AUC, (E) the median glucose value based on a CGM from a 7-day sampling every 5 min, or (F) the difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles of glucose values based on a CGM from a 7-day sampling every 5 min, (G) HbA1c, (H) log2-transformed FPIR, as well as two measures of homeostasis model assessment (HOMA): (I) log2-transformed HOMA2-%B quantifying beta cell function, and (J) log2-transformed HOMA2-%S quantifying insulin sensitivity. HOMA2-%B and HOMA2-%S were calculated using the HOMA2 model available from: www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator/. We used the “Insulin” tab in the “Excel spreadsheet implementation” with fasting glucose (in mmol/L) and fasting insulin measured using radioimmunoassay (in pmol/L) as inputs [19, 20].

Simple linear regression was used to evaluate whether there is an association between the different glucose metabolism measures. First, we estimated the association between log2-transformed glucose AUC and log2-transformed FPIR. We then estimated the associations between the 7-day CGM glucose measurements summarized in two ways and treated as the outcome ((A) the median value for each individual or (B) the difference between 75th and 25th percentiles of the 7-day CGM glucose values), and one of four glucose metabolism measures treated as a predictor (log2-tranformed FPIR, HbA1c, 2 h OGTT glucose, or log2-transformed OGTT glucose AUC), adjusting for age and sex. All analyses were performed in R (www.r-project.org).

Results

There were nine autoantibody combinations identified among the 57 subjects (Table 2). The three most frequent autoantibody combinations were: (A) IAA, GADA, IA-2A and at least one of ZnT8(W/Q/R)A (n = 12; 21.1%), (B) GADA, IA-2A and at least one of ZnT8(W/Q/R)A (n = 10; 17.5%) as well as (C) GADA and at least one of ZnT8(W/Q/R)A (n = 10; 17.5%) (Table 2). The distribution of the fasting glucose measurements at visit 1 and 2 (Fig. 1A), as well as HbA1c at visit 1 and 2 (Fig. 1B) show that the fasting glucose and HbA1c, remained stable between the two visits (p-value 0.99, 0.27, respectively).

The distribution of fasting glucose (mmol/L) (1A) and HbA1c (mmol/mol) (1B) at visits 1 and 2 (n = 57). The boxplot indicates the median, the interquartile range, the violin around the boxplot shows the shape of the distribution of values at each visit, with individual data points shown in grey. The fasting glucose was measured 10 min before the start of IvGTT at visit 1 and OGTT at visit 2. The dashed lines at 7 mmol/L in 1A and at 42 mmol/mol in 1B indicate the World Health Organization thresholds above which subject is considered to be diabetic. Fasting glucose measurements were not found to differ between visits 1 and 2, nor did HbA1c at visits 1 and 2 (Wilcoxon test p-value 0.99 and 0.27, respectively)

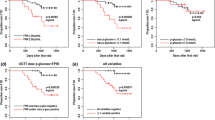

The relationships between three different measures of glucose metabolism are illustrated in Fig. 2: glucose based on OGTT (panels 2A and 2B), FPIR based on IvGTT (panel 2B), and glucose based on a 7-day CGM (panel 2C). We noted three subjects (shown in red) who at 120 min remain above the ADA (American Diabetes Association) threshold for diabetes (11.1 mmol/L), as well as four subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (shown in orange) according to the ADA guidelines (Fig. 2A). Those seven subjects tended to have lower FPIR values and higher log2-transformed OGTT glucose AUC compared to the other subjects. The estimate of the linear relationship between log2-transformed FPIR as the outcome and log2-transformed OGTT glucose AUC as the predictor, adjusting for age and sex was − 1.88 (− 2.71, − 1.05) p = 3.49 × 10− 5 (Supplementary Table 2, Additional file). Higher measures of log2-transformed OGTT glucose AUC were associated with lower log2-transformed FPIR mU/L, specifically, the doubling in the OGTT glucose AUC value was associated with a FPIR (mU/L) value 6.6 (2.9, 15.0) times lower (Fig. 2B).

Assessment of glucose metabolism based on OGTT (2A and B), IvGTT (2B) (n = 57) and CGM (2C) (n = 24). In panel 2A we show the individual trajectories of blood glucose measured using a 2-h OGTT test at visit 2. Based on glucose values at minute 120, we identified 7 subjects (labelled with red and orange subject labels) would be considered to have impaired glucose tolerance (orange labels) or to have clinical type 1 diabetes (red labels) according to the World Health Organization (see grey panel in 2A). In panel 2B we show a scatterplot and a regression line between the log2-transformed area under the curve (AUC) of OGTT glucose measurements versus the log2-transformed FPIR measurements from IvGTT at visit 1. The subjects labelled in orange and red correspond to those in panel 2A. In panel 2C we present the distributions of the glucose measurements obtained from the Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) over a 7-day period starting at visit 2. The subjects were sorted according to an increasing median glucose value. The individual glucose measurements are shown as points, with the boxplots showing the median and interquartile range, and the violin plot showing the distribution of the CGM glucose values for a given individual. The subjects shown in orange and red correspond to those in panels 2A and 2B

The 7-day CGM glucose data for 24 subjects for whom the CGM data was available are shown in Fig. 2C. The CGM profiles are summarized using boxplots overlayed with violin plots showing the range and the distribution of the glucose values for each individual over the course of 7 days. The spread of the data, shown both as a boxplot and a density around it, seemed to increase as the median CGM glucose value increased for subjects shown from left to right, from lowest to highest median CGM glucose value. The individual CGM data shown in red corresponds to the three individuals in red in panels 2A and 2B. Two of the four subjects with impaired glucose tolerance are shown in orange (the CGM data for the other two individuals in that group was not available).

The results of the analysis to evaluate the association between six glucose metabolism measures (from OGTT, IvGTT and CGM) and autoantibody count, status and type, are summarized in Supplementary Table 3, Additional file. There were no associations found between glucose metabolism and islet autoantibodies. There seemed to be an indication that the presence of at least one of ZnT8(Q/R/W)A was associated with a lower log2-transformed FPIR mU/L (− 0.80 (− 1.58, − 0.02), p = 0.046), but we consider this as a hypothesis-generating result, due to the overall number of tests performed in this analysis (Table 3, Fig. 3).

FPIR (mU/L) levels and autoantibody status. The distribution of log2-transformed first-phase insulin response (FPIR) (mU/L) stratified by presence of IAA, GADA, IA-2A or ZnT8(Q/R/Q)A (n = 57). The boxplot indicates the median, the interquartile range, the violin around the boxplot shows the shape of the distribution, with individual data points shown in grey. Based on the model in Table 3 with the status of the four antibodies as the main predictor, adjusted for age and sex, log2(FPIR) was not found to be statistically significantly different depending on the status of IAA, GADA or IA-2A (p = 0.564, 0.637, 0.262), but there was some evidence suggesting that FPIR is lower for those with at least one of ZnT8(Q/R/W)A present compared to those with no ZnT8(Q/R/W)A (1.74 mU/L lower (95% CI = 1.01, 2.99), p = 0.046)

We noted that ZnT8(Q/R/W)A was the only autoantibody measure that, in our analysis, indicates a consistent trend with all glucose metabolism measures. Specifically, the direction of the estimates for all glucose metabolism measures was positive with higher values of glucose AUC and negative for FPIR with lower first phase insulin response. Additionally, we noted an association between log2-transformed OGTT C-peptide AUC, as well as log2-transformed OGTT insulin AUC and age (Supplementary Table 3, Additional file).

The association between the two summaries of the 7-day CGM glucose measurements and glucose metabolism measures based on OGTT and IvGTT are summarized in Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1, Additional file. The results are statistically significant for all associations tested, with both the median and the spread of the CGM glucose data being associated with higher glucose values based on OGTT, higher HbA1c, and lower FPIR (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1, Additional file).

Discussion

The present study provides novel insights into the heterogeneity of islet autoantibody positive subjects in Stage 1 or Stage 2 of autoimmune type 1 diabetes. By combining fasting plasma glucose at two different visits 1 month apart with HbA1c, IvGTT for FPIR at the first visit and OGTT at the second visit followed by a 7-day CGM, it was possible to delineate the research subjects into three categories. First, the major group of two or more autoantibody positive subjects did not reveal signs of deteriorated glucose metabolism in any of the five measurements. This is of interest as research subjects belonging to this category varied from having two to four autoantibodies. Second, presenting with fasting glucose in the normal range, there were four (4/57) subjects (ID-02, ID-45, ID-23 and ID-20) who showed impaired glucose tolerance since the 120-min glucose values varied were within the 7.8–11.1 mmol/l range (Fig. 2). All four had reduced FPIR as well correlating to increased log2-transformed glucose AUC (Fig. 2B). Third, three (3/57) subjects (ID-03, ID-26 and ID-32) who by 120 min OGTT showed diabetes values which correlated to reduced FPIR (Fig. 2B). None of these three subjects showed any symptoms of diabetes. One OGTT with diabetes values with no concurrent symptoms is not sufficient for a diabetes diagnosis according to the ADA recommendations [21]. A second OGTT was not carried out. Taken together, the research subjects represented individuals who were screened because they were relatives to a subject at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes who were followed in the TEDDY [17] or DiPiS [22] studies. Only 7/57 (12%) were screened because they had a first degree relative with type 1 diabetes. We found that the majority (50/57) had glucose metabolism and beta-cell function within the normal range while 7/57 deviated from normal. The majority would therefore qualify in a secondary prevention trial where the risk for clinical onset would be about 70% in 10 years [7]. The smaller group of seven Stage 2 individuals would on the other hand perhaps be more suitable to be recruited into a secondary prevention trial aiming at preserving a deteriorating beta-cell function such as the recent trial with teplizumab [23]. The major finding is therefore that staging subjects into Stage 1 or 2 are best performed by a baseline IvGTT (the short version for FPIR would suffice) followed by an OGTT prior to randomization into a Stage 1or Stage 2 trial, respectively. Alternatively, OGTT may suffice as FPIR did not add additional subjects with impaired glucose tolerance.

Although not all subjects participated with CGM, five out of these seven subjects did. As CGM correlated well to aberrant OGTT and FPIR, our data therefore suggest that CGM should be considered as one additional approach to stage multiple autoantibody positive subjects prior to being randomize in secondary prevention studies. The combination of glucose metabolism measures and information on autoantibody status, count and type is likely to provide a more accurate estimate on the stage in the autoimmune process leading to clinical onset of type 1 diabetes than autoantibody status alone. Using the autoantibody information alone to determine the stage of the disease process appears to result in an inaccurate staging of the disease.

The observation that the mere presence of ZnT8A (any of the three variants) seemed to be associated with a more advanced deteriorated beta-cell function merits further investigation. In a previous baseline study of 47 children, [24] we observed that number and levels of autoantibodies were not associated with glucose metabolism, except for an increased frequency and level of ZnT8QA in children with impaired glucose metabolism [15]. This preliminary confirmation is of particular interest as the possible association between ZnT8A and progression to clinical onset of diabetes in multiple autoantibody positive subjects is poorly understood. Newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with the CC (ZnT8R/R) and CT (ZnT8R/W) genotypes of the rs13266634 SNP of the SLC30A8 gene had higher stimulated C-peptide levels the first year after onset compared with TT (ZnT8W/W) subjects [25, 26]. This is of interest as the SLC30A8 genotype may be important to consider as a factor that contributes to progression to clinical onset of diabetes. Patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes who were positive for ZnT8A were more frequently of older age, had less ketoacidosis and carried more often HLA DQB1*06:04 [27, 28]. Screening of first-degree relatives using IA-2A and ZnT8A alone allowed identification of the majority of rapidly progressing siblings and offspring [29]. Although ZnT8A are only considered as a useful additional risk marker [30], perhaps considering their levels [31], our previous [15] and present observation would require further studies into the association between ZnT8(W/R/Q)A and deteriorating beta-cell function.

Our study has some limitations. The number of subjects with multiple islet autoantibodies was not large. The study group was also dominated by subjects who were relatives, not to type 1 diabetes patients, but rather to subjects identified at birth because they had an increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes such as subjects from the DIPP [32], DiPiS [22] and TEDDY [16] studies. The inclusion criterion for these studies were merely increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes rather than the proband had developed islet autoantibodies or type 1 diabetes. However, despite the small number of subjects, the findings on glucose metabolism were clearly statistically significant. Swedish subjects were older than Finnish subjects, but age was taken into account in statistical models, and there were no apparent differences in results between study sites.

The use of fasting glucose, IvGTT, or OGTT, alone or in combination, to randomize subjects with multiple islet autoantibodies into secondary prevention trials in Stage 1 or Stage 2 cohorts is much discussed. Alternative methods to consider may be assessment of the beta-cell mass by both acute insulin response to arginine at hyperglycemia (AIRmax), as a correlate of beta-cell mass, and beta-cell function by (IvGTT) [33]. The IvGTT and FPIR may detect an acceleration in the loss of beta-cell function which may not be seen by OGTT [34]. The baseline heterogeneity observed in earlier studies of multiple islet autoantibody positive subjects that complicates secondary prevention [35] needs further considerations perhaps by taking into account the endotypes of type 1 diabetes defined by whether IAA (primarily in HLA DR4-DQ8 subjects) or GADA (DR3-DQ2 subjects) would be considered as the first appearing islet autoantibody [3, 5, 32]. Apart from further studies on CGM, it will also be worthwhile to consider levels of the islet autoantibodies, in particular ZnT8A, other non-HLA genetic factors, measures of insulin sensitivity such as HOMA-IR [36] along with BMI and family history of type 2 diabetes.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that research subjects to be randomized to clinical trials for prevention of type 1 diabetes can be categorized more accurately when OGTT, IvGTT, and CGM are used prior to inclusion into prevention studies in addition to measurement of islet autoantibodies.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations

- ADA:

-

American Diabetes Association

- CGM:

-

Continuous Glucose Monitoring

- DiPiS:

-

Diabetes Prediction in Skåne

- DIPP:

-

Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention

- FPIR:

-

First Phase Insulin Response

- HOMA:

-

Homeostasis model assessment

- GADA:

-

GAD65 (glutamate decarboxylase 65) autoantibody

- IAA:

-

Insulin autoantibody

- IA-2A:

-

Islet antigen-2 autoantibody

- IvGTT:

-

Intravenous glucose tolerance test

- OGTT:

-

Oral glucose tolerance test

- TEDDY:

-

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young

- TrialNet:

-

Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet

- ZnT8(W/Q/R)A :

-

Zinc transporter 8 autoantibody, any of the three variants at position 325

References

Sioofy-Khojine AB, Lehtonen J, Nurminen N, Laitinen OH, Oikarinen S, Huhtala H, et al. Coxsackievirus B1 infections are associated with the initiation of insulin-driven autoimmunity that progresses to type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2018;61(5):1193–202.

Vehik K, Lynch KF, Wong MC, Tian X, Ross MC, Gibbs RA, et al. Prospective virome analyses in young children at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2019;25(12):1865–72.

Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Schatz DA, Ilonen J, Lernmark A, Hagopian WA, et al. The 6 year incidence of diabetes-associated autoantibodies in genetically at-risk children: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia. 2015;58(5):980–7.

Ilonen J, Hammais A, Laine AP, Lempainen J, Vaarala O, Veijola R, et al. Patterns of beta-cell autoantibody appearance and genetic associations during the first years of life. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3636–40.

Krischer JP, Liu X, Vehik K, Akolkar B, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ, et al. Predicting islet cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: an 8-year TEDDY study Progress report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(6):1051–60.

Vehik K, Bonifacio E, Lernmark Å, Yu L, Williams A, Schatz D, et al. Hierarchical order of distinct autoantibody spreading and progression to type 1 diabetes in the TEDDY study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(9):2066–73.

Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O, Simell T, Lempainen J, Steck A, et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2473–9.

Koskinen MK, Helminen O, Matomäki J, Aspholm S, Mykkänen J, Mäkinen M, et al. Reduced β-cell function in early preclinical type 1 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(3):251–9.

Koskinen MK, Lempainen J, Löyttyniemi E, Helminen O, Hekkala A, Härkönen T, et al. Class II HLA genotype Association with first-phase insulin response is explained by islet autoantibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(8):2870–8.

Koskinen MK, Mikk ML, Laine AP, Lempainen J, Löyttyniemi E, Vähäsalo P, et al. Longitudinal pattern of first-phase insulin response is associated with genetic variants outside the class II HLA region in children with multiple autoantibodies. Diabetes. 2020;69(1):12–9.

Notkins AL, Lernmark Å. Autoimmune type 1 diabetes: resolved and unresolved issues. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(9):1247–52.

Wenzlau JM, Juhl K, Yu L, Moua O, Sarkar SA, Gottlieb P, et al. The cation efflux transporter ZnT8 (Slc30A8) is a major autoantigen in human type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(43):17040–5.

Wherrett DK, Chiang JL, Delamater AM, DiMeglio LA, Gitelman SE, Gottlieb PA, et al. Defining pathways for development of disease-modifying therapies in children with type 1 diabetes: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1975–85.

Martinez MM, Salami F, Larsson HE, Toppari J, Lernmark Å, Kero J, et al. Beta cell function in participants with single or multiple islet autoantibodies at baseline in the TEDDY family prevention study: TEFA. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2021;4(2):e00198.

Andersson C, Carlsson A, Cilio C, Cedervall E, Ivarsson SA, Jonsdottir B, et al. Glucose tolerance and beta-cell function in islet autoantibody-positive children recruited to a secondary prevention study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2013;14(5):341–9.

Hagopian WA, Erlich H, Lernmark A, Rewers M, Ziegler AG, Simell O, et al. The environmental determinants of diabetes in the young (TEDDY): genetic criteria and international diabetes risk screening of 421 000 infants. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12(8):733–43.

Vehik K, Fiske SW, Logan CA, Agardh D, Cilio CM, Hagopian W, et al. Methods, quality control and specimen management in an international multicentre investigation of type 1 diabetes: TEDDY. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29(7):557–67.

Lampasona V, Pittman DL, Williams AJ, Achenbach P, Schlosser M, Akolkar B, et al. Islet autoantibody standardization program 2018 workshop: Interlaboratory comparison of glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody assay performance. Clin Chem. 2019;65(9):1141–52.

Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(12):2191–2.

Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1487–95.

Association AD. Abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2021;39(1):14–43.

Larsson HE, Lynch K, Lernmark B, Hansson G, Lernmark A, Ivarsson SA. Relationship between increased relative birthweight and infections during pregnancy in children with a high-risk diabetes HLA genotype. Diabetologia. 2007;50(6):1161–9.

Herold KC, Bundy BN, Long SA, Bluestone JA, DiMeglio LA, Dufort MJ, et al. An anti-CD3 antibody, Teplizumab, in relatives at risk for type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):603–13.

Delli AJ, Vaziri-Sani F, Lindblad B, Elding-Larsson H, Carlsson A, Forsander G, et al. Zinc transporter 8 autoantibodies and their association with SLC30A8 and HLA-DQ genes differ between immigrant and Swedish patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the better diabetes diagnosis study. Diabetes. 2012;61(10):2556–64.

Nielsen LB, Vaziri-Sani F, Pörksen S, Andersen ML, Svensson J, Bergholdt R, et al. Relationship between ZnT8Ab, the SLC30A8 gene and disease progression in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity. 2011;44(8):616–23.

Brorsson C, Vaziri-Sani F, Bergholdt R, Eising S, Nilsson A, Svensson J, et al. Diabetes DSGoC: correlations between islet autoantibody specificity and the SLC30A8 genotype with HLA-DQB1 and metabolic control in new onset type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity. 2011;44(2):107–14.

Salonen KM, Ryhänen S, Härkönen T, Ilonen J, Knip M, Register FPD. Autoantibodies against zinc transporter 8 are related to age, metabolic state and HLA DR genotype in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29(8):646–54.

Andersson C, Larsson K, Vaziri-Sani F, Lynch K, Carlsson A, Cedervall E, et al. The three ZNT8 autoantibody variants together improve the diagnostic sensitivity of childhood and adolescent type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity. 2011;44(5):394–405.

Gorus FK, Balti EV, Vermeulen I, Demeester S, Van Dalem A, Costa O, et al. Screening for insulinoma antigen 2 and zinc transporter 8 autoantibodies: a cost-effective and age-independent strategy to identify rapid progressors to clinical onset among relatives of type 1 diabetic patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;171(1):82–90.

Long AE, Gooneratne AT, Rokni S, Williams AJ, Bingley PJ. The role of autoantibodies to zinc transporter 8 in prediction of type 1 diabetes in relatives: lessons from the European Nicotinamide diabetes intervention trial (ENDIT) cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(2):632–7.

Sosenko JM, Skyler JS, Palmer JP, Krischer JP, Yu L, Mahon J, et al. The prediction of type 1 diabetes by multiple autoantibody levels and their incorporation into an autoantibody risk score in relatives of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2615–20.

Ilonen J, Lempainen J, Hammais A, Laine AP, Härkönen T, Toppari J, et al. Primary islet autoantibody at initial seroconversion and autoantibodies at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes as markers of disease heterogeneity. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(2):284–92.

Hao W, Woodwyk A, Beam C, Bahnson HT, Palmer JP, Greenbaum CJ. Assessment of β cell mass and function by AIRmax and intravenous glucose in high-risk subjects for type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(12):4428–34.

Veijola R, Koskinen M, Helminen O, Hekkala A. Dysregulation of glucose metabolism in preclinical type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016;17(Suppl 22):25–30.

Elding Larsson H, Larsson C, Lernmark Å. Group D-is: baseline heterogeneity in glucose metabolism marks the risk for type 1 diabetes and complicates secondary prevention. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52(3):473–81.

Siljander HT, Hermann R, Hekkala A, Lähde J, Tanner L, Keskinen P, et al. Insulin secretion and sensitivity in the prediction of type 1 diabetes in children with advanced β-cell autoimmunity. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169(4):479–85.

Acknowledgements

The research subjects are acknowledged for their participation and interest in the study. We thank the following member in the Swedish TEFA study group for expert technical support: Anita Ramelius, Ida Jönsson, Rasmus Bennet, Birgitta Sjöberg, Åsa Wimar, Jessica Melin, Maria Ask, Anne Wallin, Monika Hansen, Susanne Hyberg, Karin Ottosson, Jenny Bremer, Ulla-Marie Carlsson, Ulrika Ulvenhag, Anette Sjöberg, Marielle Lindström, Lina Fransson, Fredrik Johansen, Kobra Rahmati, Zeliha Mestan, Evelyn Tekum-Amboh, Silvija Jovic, Joanna Gerardsson, Emelie Ericson-Hallström, Sofie Åberg, Sara Sibthorpe. In the Finnish TEFA study group we thank for excellent technical support: Elina Mäntymäki, Sini Vainionpää, Minna Romo, Zhian Othmani, Eeva Varjonen, Sanna Jokipuu, Satu Ruohonen, Laura Leppänen, Petra Rajala, Eija Riski, Miia Kähönen, Minna-Liisa Koivikko, Tea Joensuu, Heidi Alanen, Teija Mykkänen, Tiina Latva-aho, Minna-Liisa Koivikko, Aino Stenius, Paula Ollikainen, Marika Korpela, Katja Multasuo, Päivi Salmijärvi, Pieta Kemppainen, Merja Runtti, Riitta Päkkilä, Irene Viinikangas, Sinikka Pietikäinen and Tuula Arkkola.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. Supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (2-SRA-2014-309-M-R), the National Institutes of Health for the TEDDY family subjects (1UO1 DK063861), the Swedish Research Council (Dnr 2020–01537 and Strategic Research Area Exodiab, Dnr 2009–1039) as well as the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (Dnr IRC15–0067). In Finland support was received by the JDRF (grants 2-SRA-2014-309-M-R, 1-SRA-2016-342-M-R and 1-SRA-2019-732-M-B), Special Research funds for Turku, Oulu and Tampere university hospitals in Finland, the Academy of Finland (Decision numbers 292538, 250114 and 308067), the Diabetes Research Foundation in Finland, the Pediatric Research Foundation in Finland, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, the Emil Aaltonen Foundation and the Alma and KA Snellman Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

ÅL and HEL conceived the original idea. MMM, FS, JK and SP contributed to study subject recruitment and CT coordinated the overall conduct and data base management of the study. MM and LS prepared the analysis data base in R and performed all statistical analyses. ÅL and MM drafted the manuscript. CT, MMM, FS, DA, JT, JK, RV, PT, SP, ML, HB, AK, HEL and MK reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The TEFA study was approved in Sweden by the Regional Ethics Board (dnr 2015/459) and amendment by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr 2020–06990) and in Finland by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland in Turku, Finland. All research subjects signed an informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Martinez, M.M., Spiliopoulos, L., Salami, F. et al. Heterogeneity of beta-cell function in subjects with multiple islet autoantibodies in the TEDDY family prevention study - TEFA. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 7, 23 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-021-00135-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40842-021-00135-6