Abstract

To date, no systematic attempt has been made to describe the main features of the Italian policy advisory system. In particular, we know very little about the role of political scientists within it. This study addresses precisely this gap in the literature. First, by presenting original data derived from an online survey to which 177 Italian political scientists responded, we reconstruct frequency, type, recipient(s), and areas of their (potential) policy advice. Second, by focusing on two very relevant policy processes—the approval of the so-called Italicum (electoral law) and of the so-called Jobs Act (labour market reform)—we add insightful qualitative details to our quantitative analysis. Empirical results show that Italian political scientists are seldom engaged in policy advisory activities: many of them have never been. Moreover, there are no particular differences—from the point of view of personal characteristics (gender and level of academic career)—between policy advisors and the so-called pure academics. Finally, as the two case studies show, informal advice has the greatest impact on policymaking. This latter aspect reminds us of how much the Italian policy advisory system (PAS) is still poorly institutionalised and largely based on personal relationships as well as on political proximity.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 The Policy Advisory Roles of Italian Political Scientists

1.1 The Italian Policy Advisory System

To date, nosystematic attempt has been made to describe the main features of the Italian policy advisory system—with respect to its components, interactions, and dynamics (Halligan, 1995), or the stock of its analytical capacities (Howlett, 2009). Nonetheless, the peculiarities of the Italian political system and policymaking suggest a weakly institutionalised system of advice where policy knowledge is dispersed vertically across levels of government (Dente, 1997) and horizontally across society and policy sectors (Dente, 1995). In fact, the consolidation of a quasi-federalist form of state has empowered local governments, particularly regions and municipalities, with responsibilities for specific policy sectors, including health, social welfare, and economic development (Lippi, 2011). At the same time, the ‘quasi-majoritarian turn’ that characterised the political system at the beginning of the 1990s affected the party system, starting a never-ending transition from multipartitism to a ‘fragmented bipolarism’ of coalition governments, the latter of which is now challenged by new entrants, such as the 5-Star Movement and the League (previously the ‘Northern League’) (Chiaramonte et al. 2018). These transformations have lately highlighted the consensual, albeit still polarised, character of a system where political parties continue to play a central role also in politicising the public administration. In the so-called Second Italian Republic, the number of policy advisors who have been appointed due to their political affiliations (or at least, ideological affinity) is even higher than it was in the past (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016).

Against this backdrop, the Italian case shows scarce administrative capacity at the ministerial level, with legal expertise still prevailing (Capano & Gualmini, 2011; Ongaro, 2008; Capano & Vassallo, 2003; Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016). Governmental analytical capacity is strongly focused on the law-making process, thus favouring the legal expertise of legislative offices over other types of knowledge (Regonini, 2017). The few studies of the Italian case conducted to date have focused on the composition of specific administrative branches, such as ministerial offices (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016), with particular attention paid to political appointments and politicisation, rather than policy advice per se. In particular, the changes in the party system have increased the ministerial advisors’ vulnerability to government change and reshuffles, with high turnover rates negatively impacting the advisors’ level of professionalisation (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016: 520).

Advisory activities can be deduced from the statutory dispositions of governing public agencies and public and private research institutions and from the thick knowledge of the policy process in different policy fields. At the national level, in-house policy advisory activities are traditionally performed by ministerial cabinets (called ‘uffici di diretta collaborazione’ since 1999) and by legislative offices. In particular, ministerial cabinets developed in post-war Italy as large in-house institutionalised advisory structures designed to bypass the mistrusted senior civil servants; they play a central role in policy formulation and executive activities (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2013). These ministerial advisors are usually qualified lawyers (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016). Other actors performing advisory activities include the public bodies and administrative agencies with technical expertise in a specific policy area, such as the ISS—Istituto Superiore di Sanità (National Institute of Health), the INPS—Istituto Nazionale per la Previdenza Sociale (National Social Security Institute), and the CNEL—Consiglio Nazionale dell’Economia e del Lavoro (National Council of Economy and Labour). Traditionally, advisory functions can be performed also by temporary ad hoc committees in Parliament (e.g. the Commissione Onofri for the reform of the social welfare system in the 1990s). At the same time, external-to-government policy advice provision (by academics, think tanks, professional consultants, etc.) is traditionally weakly institutionalised. The common practice is for the Prime Minister and other Ministers to appoint consultants, mainly economists and legal scholars, but very few political scientists.

Among the recent trends observed in the PAS literature (differentiation, externalisation, and politicisation of the PAS) (Craft & Howlett, 2012, 2013; Craft & Halligan, 2017), the Italian case shows signs of differentiation both within and outside of government and the civil service. In terms of internal advisory bodies, the Bassanini Reform (Italian Legislative Decree no. 300/1999) tasked the ministerial cabinets with formulating and evaluating public policy (Dente, 1995). The recent Madia Reform (Italian Law no. 124/2015) required government to assign specific powers governing the analysis, design, and evaluation of public policies, to the Prime Minister’s Office (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016). This measure should have echoed the French experience with the Révision Générale des Politiques Publiques (RGPP, General Review of Public Policies). However, the corresponding legislative decree was never approved. At the same time, soliciting the advice of individual experts is a common practice in Parliamentary committees and Ministries.

Looking beyond the core executive and the Parliament, the provision of policy advice also mushroomed among public research institutes and independent private think tanks. The advisory function of public research institutes such as the INAPP—Istituto Nazionale per l’Analisi delle Politiche Pubbliche (National Institute for Public Policy Analysis) or the ISPRA—Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (Institute for Environmental Protection and Research) (Guaschino, 2018) was recently acknowledged by Italian Legislative Decree no. 218/2016. At the sub-national level, regional governments may rely on institutional advisors, as in the cases of Polis in Lombardy (Cattaneo, 2018) and of IRPET—Istituto Regionale Programmazione economica della Toscana (Regional Institute for Economic Planning of Tuscany) in Tuscany. At the same time, private research institutes and think tanks are creating a variegated supply of policy advice, with their research findings often presented in the national media. Even though we still lack an updated mapping of these subjects, a number of other think tanks sponsored by different political parties have proliferated (Diletti 2011). All in all, policy advice continues to be delivered mostly on an individual basis by academics, in particular by law scholars and economists. By contrast, political scientists only seldom engage in providing policy advice, with no particular differences with regard to gender or academic career position. Yet, when they do, they generally provide advice on a few specific issues, such as the public administration and the electoral system, international relations and the European Union (EU), immigration policy and civilrights (for further details, see Sect. 10.2).

In sum, there is some evidence of the growing differentiation of the Italian PAS, as in all European countries (Hustedt & Veit, 2017). Still, the impact of these trends on the ‘quality’ (i.e. the degree of innovation, internal coherence, and evidence-based content) of policymaking in Italy remains negligible (Capano & Pritoni, 2016).

1.2 Italian Political Scientists in the Policy Advisory System

Regarding where academics and scientists are located within the PAS (Blum & Brans, 2017), the (scarce) evidence relating to the Italian case suggests that scientists mainly populate the academic arena, while also maintaining a presence at the intersection with the governmental arena (with a variety of governmental research institutes) and at the intersection with the societal arena, where researchers work as consultants in the research centres of various interests groups and private foundations. Law scholars represent the vast majority of scientists and academics acting as experts and public intellectuals in public debate and are also key figures within the governmental arena (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2013). Political scientists, on the other hand, being a relatively ‘new’ academic discipline, constitute a numerically limited group of experts of rather ‘marginal’ importance to public debate (Capano & Verzichelli, 2016); as such, they are seldom involved in Italian policymaking. Italian political scientists tend to be concentrated in the academic arena (in particular universities and few policy research institutes), while sometimes appearing in the media as opinion-givers on political and partisan matters, but rarely accessing the governmental arena as policy experts. The type of advice that political scientists tend to give can vary extremely. Political scientists are rarely involved in giving policy advice on substantive and procedural matters (Craft & Howlett, 2012). The case of electoral experts is a partial exception to this pattern, but there are very few cases where political scientists produce, or are requested to prepare, reports on a specific policy problem, or are involved in the formal evaluation of public policies. Most of the time, their policy advice is long term and anticipatory when they write in scientific journals and more short term and reactive when they write editorials for newspapers. Anecdotal experience also suggests that the more procedural policy advice is informally channelled in cases of mutual recognition and trust between a policymaker and a political scientist.

The main access points for political scientists as academics to bring their expertise to bear on policymaking are based on previous personal or professional knowledge shared by the policymaker and the academic. This mode of access is not frequent and is poorly institutionalised. In very rare circumstances, Italian political scientists are invited to join governmental agencies or parliamentary committees. Few political scientists are engaged in the societal arena, especially when promoting participatory practices at local level through associations and NGOs. Specialists in elections and social media may also bridge the academic and societal arenas, creating a genuine business of applied research into political and policy matters.

2 Political Scientists: Types of Advisory Role in Italy

To date, there has been no comprehensive mapping of all the cases where an Italian political scientist has been engaged in policymaking. This is the reason why the data we present and discuss in this chapter are useful and, above all, innovative. Thanks to an online survey, 177 Italian political scientists responded to a broad set of different questions on their (potential) advisory roles. Even though our sample appears to be quite small for a large country like Italy, it is highly representative of the Italian community of political scientists, which is actually rather limited in size. More precisely, the response rate to the online survey was 61.0% (177 responses to a total of 290 invitations), with no particular differences with regard to gender or academic career status. Despite this relatively high response rate, the numbers invite the conventional caution when it comes to drawing conclusions. The responses to this broad set of questions allow us to differentiate Italian political scientists and to ‘categorise’ them. More precisely, our classification makes reference to a typology of policy advisors which divides academics into four categories: the ‘pure academic’, the ‘expert’, the ‘opinionating scholar’, and the ‘public intellectual’ (see Chap. 2).

The first main step to take is to analyse how frequently Italian political scientists (from now on IPSs) engage in different kinds of policy advice provision. Table 10.1 sets out the answers that Italian academics gave to the survey questions regarding six different kinds of policy advice: (i) providing data and facts about policies and political phenomena; (ii) analysing and explaining the causes and consequences of policy problems; (iii) evaluating existing policies, institutional arrangements, and so on; (iv) offering consultancy services and advice and making recommendations on policy alternatives; (v) making forecasts and/or carrying out polls; (vi) offering value judgements and normative arguments.

A large share of Italian political scientists do not provide policy advice. This finding is particularly clear with respect to their making forecasts and/or carrying out polls (68.4% of respondents has never done so) but can reasonably be extended to all kinds of advice. This is a first—fairly preliminary—confirmation of what we claimed in previous sections: in Italy, political scientists are seldom consulted by policymakers. The latter prefer to collaborate with legal experts and, subordinately, with economists (in particular with regard to policy evaluation and policy recommendations). However, there appears to be a select sort of ‘inner circle’ of political scientists who, on the contrary, are very much concerned with policymaking. A dozen Italian academics are rather frequently (‘once a week’ or ‘once a month’ answers) engaged in policy advising: policymakers usually refer to their expertise in various areas, and their scientific knowledge is frequently a value added for designing and implementing policies.

If we cross-tabulate frequency and type of advice, we can thus categorise Italian political scientists who responded to our online survey, according to the typology presented in Chap. 2. How many ‘pure academics’, ‘experts’, ‘opinionators’, and ‘public intellectuals’ can be identified among political scientists in Italy? (Table 10.2)

In Italy only one political scientist in the survey could be classified as a ‘publicintellectual’ on the basis of our criteria. This means that only one Italian political scientist (hereafter abbreviated to IPS) offers different types (normative arguments included) of advice very frequently (at least on a once a month basis). On the contrary, around one IPS out of four can be identified as a ‘pure academic’: she/he never offers policy advice of any kind. Finally, the vast majority of IPSs can be classified as either ‘experts’ or ‘opinionators’, with the latter representing the modal category in our distribution. However, within those categories, the vast majority of respondents are seldom involved in the provision of policy advice (with answers that very often are ‘once a year’ or even ‘less frequently’). Therefore, this empirical finding does not contradict the qualitative view that Italian political scientists are scarcely involved in policymaking (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016).

Yet, more interesting than the simple categorisation itself is reflecting on the most likely factors that influence that same categorisation. In other words, what impacts the likelihood that Italian political scientists give more or less advice in more or less different ways? With respect to this, the easiest answer seems to involve personal factors. It might be, for instance, that political scientists on permanent contracts are more involved in policy advice than political scientists on temporary contracts or that males are more involved than females.

We shall start by examining the temporary/permanent distinction. Tenured political scientists are generally older than their non-tenured colleagues and thus will have had more time to develop those personal relationships that are so important to any involvement in policy advisory activities in Italy. Non-tenured political scientists, in turn, are naturally more interested in teaching, and above all in doing research aimed at the publication of articles and books, than in providing policy advice, since their academic record (and thus their publications and teaching experience) will decide whether or not they can secure tenure in the near future. Academic careers are mainly based on teaching and research, not on policy advice provision. To empirically test these expectations, we cross-tabulated the distribution of Italian political scientists in different categories with whether they have (or do not have) a permanent contract with a university (Table 10.3).

Quite surprisingly, whether an IPS occupies either a permanent or a temporary position in academia does not have much impact on the likelihood that she/he will be classified as a pure academic, an expert, an opinionator, or a public intellectual. Indeed, although the only Italian public intellectual responding to the survey holds a tenured position, it is not possible to establish any particular differences between tenured and non-tenured political scientists. This empirical finding, precisely because it is highly surprising, merits further research in the near future.

Another potential driver of the likelihood of providing policy advice could be linked to gender issues. More precisely, it might be that in a patriarchal society like Italy (even in these initial 20 years of the twenty-first century), men are more likely to be involved in the provision of policy advice than women are. Accordingly, we would expect to find many more women than men in the ‘pure academic’ category, whereas it is highly likely that the only Italian public intellectual will be male. What do our data tell us about gender issues?

On the one hand, Table 10.4 confirms the fact that the only self-declared public intellectual among the political scientists surveyed in Italy is male. On the other hand, women are characterised by a higher percentage of experts and opinionating scholars than men are, whereas the opposite holds true for men classified as pure academics. In other words, if a bias really exists, this seems to work in favour of, rather than against, women. However, we are considering just a few dozen cases, and it could be misleading to draw such conclusions from the data available. Once again, further research will help us analyse in greater depth and better understand this very interesting empirical finding.

Yet, regardless of the typology, many other characteristics of advice are interesting to analyse. As regards the formal or informal nature of their advice, for example, IPSs tend to use both formal and informal channels. To be honest, this empirical finding is not unexpected. Generally, experts are formally called on to participate in policymaking, while their advice can be provided both in formal settings (in the meetings of advisory bodies, for example) and on informal occasions (e.g. in phone conversations or face-to-face encounters). This finding can also be read from a second perspective, that of the (weak) institutionalisation of the policy advisory roles (of political scientists) in Italy. When policy advice is highly institutionalised and routinised, it is more likely that formal channels will prevail over informal channels (Craft & Howlett, 2013; Galanti & Lippi, 2018). By contrast, the fact that advisors tend (or are forced) to make use of informal channels to provide their advice and expertise to policymakers is a clear sign of the limited, albeit not complete lack of, institutionalisation of their role and common practices.

Thus, IPSs are seldom involved in policy advice activities, but when they are, they follow both formal and informal channels. Yet, who are policymakers actually asking for advice? In answer to this question, Table 10.5 divides recipients of advice into four broad categories: political actors, bureaucratic actors, societal actors, and international actors. These, in turn, can be further broken down into nine specific sub-categories: (i) executive politicians; (ii) legislative politicians; (iii) politicalparties; (iv) civil servants; (v) advisory bodies; (vi) think tanks; (vii) interest groups in the private and corporate sector; (viii) civilsociety organizations (CSOs); and (ix) international organizations.

First, Italian political scientists are more often engaged in providing policy advice to societal and political actors than to bureaucratic and international ones. Once again, this finding represents very interesting confirmation of what has been repeatedly argued in the literature, albeit from a qualitative rather than quantitative point of view (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2016). Bureaucratic offices would prefer to consult legal experts rather than any other kind of policy advisor. As already said, legal experts are the main protagonists within the Italian PAS, especially in relations with ministerial executives and supranational institutions. Second, there is a great difference among societal actors between interest groups in the private and corporate sector, on the one hand, and think tanks and CSOs, on the other. While the former rarely take advantage of political scientists’ advice, the latter much more frequently seek their expertise. A first tentative explanation of this striking difference relates to the left-wing bias that characterises IPSs (Curini, 2010). Probably, the interests of think tanks and CSOs are seen by academics as more legitimate than corporations’ interests. Accordingly, political scientists are more willing to provide their expertise to those whose interests they can relate to more. Moreover, it might well be that think tanks and—above all—CSOs are less endowed with expertise than interest groups in the private sector are (Bouwen, 2002). This implies that the latter do not need external policy advice, whereas other organisations do. Third, no substantial distinctions exist among different political actors (executive, legislative, parties) in terms of their asking for academics’ advice. It seems that all actors are (more or less) equally interested in the expertise of IPSs, and no particular patterns arise related to different political arenas.

Another very relevant aspect that has been scrutinised at length in our survey is the governance level of policy advice (Table 10.6).

First of all, proximity matters a lot. Italian political scientists engage in policy advice much more frequently at the sub-national and national levels of governance than at the EU and trans-national levels. This finding does not come as a surprise. In the literature (Dente, 1997), it is generally acknowledged that the demand for expertise on public policies is higher at closer levels of governance. This pattern could be mainly due to the fact that proximity enables better and tighter personal (and, in turn, professional) links and connections. However, many Italian political scientists do not provide policy advice at any level of governance.

That said, what is still lacking is a more fine-grained picture of the different policy areas where IPSs offer their advice (Table 10.7) and a further exploration of the channels through which they disseminate their expertise.

First, there appears to be a big gap between the few policy areas where many IPSs frequently give policy advice (public administration and electoral system; EU and international relations; immigration policy; civil rights) and all other policy areas. Second, among those policy areas involving a significant number of political scientists, a further distinction can be made between ‘traditional’ ‘political scientists’ areas of expertise—that is, public administration, electoral reform, international relations—on the one hand, and immigration policy and civil rights, on the other. The latter, indeed, are themes that have been very much on the public and political agenda in recent years (Chiaramonte et al. 2018). It is hence not surprising that political scientists are called on to provide their advice in relation to these particular aspects, in addition to the more conventional issues of public administration organisation, electoral system reform, and IR. Third, very few political scientists are consulted in key areas of public policy, such as health, agriculture, labour, education, environment, energy, and so on. One possible explanation for this could be the public’s acknowledgment of other disciplines as expert in policy evaluation, such as economy and sociology (at least, this is what seems to emerge from public debate).

Finally, as regards the channels of advice dissemination, it should be pointed out that the dissemination of policy advice is infrequent (regardless of the channel), which would further confirm previous empirical findings. Nevertheless, the dissemination of advice through publications and research reports is more frequent than that through policy reports and media articles (while blog/socialmedia and training courses take up an interim position between the two).

3 The Advisory Roles of Political Scientists As Taken up in Current Debates

In recent years, IPSs have played a major role in (at least) two major policy reforms that have been a constant feature of the political agenda over the last 25 years in Italy (Capano & Pritoni, 2016): the labour market reform of the Renzi government (the so-called Jobs Act: Italian Law no. 183/2014) and the electoral reform of that same government (the so-called Italicum: Italian Law no. 52/2015).Footnote 1 The choice of these two cases might offer some comparative advantages, in a sort of ‘within-case comparison’. Both reform processes involved the same prime minister, Matteo Renzi, who is deemed to display a distinctive policy style (Piattoni, 2016). While the labour market reform is considered the most important of the Renzi government, the electoral reform represented a crucial decision affecting the (informal) support for the Prime Minister from the opposition forces. Furthermore, these reforms affected sectors where IPSs have only recently acquired any prominence compared to other types of academics (law scholars and economists in particular). Therefore, this comparison reveals significant differences in the type of policy advice, in the type of engagement, and in the role that timing may have played in rendering the policy advice more or less effective (i.e. resulting in actual policy solutions).

Labour market reform had been one of Renzi’s pet projects since he took over the leadership of the PD in December 2013 (Pritoni & Sacchi, 2019). The topic was consequently one of the main topics of political debate in 2014, particularly given that Renzi took over office from his fellow PD politician Enrico Letta in late February. In a nutshell, the Jobs Act dealt mostly with four policy areas: restructuring unemployment benefits, reorganising public employment services, reviewing the range of employment contracts, and facilitating the work-life balance. In particular with regard to the first of these themes, the role of Stefano Sacchi (full professor at the Polytechnic of Turin) as expert advisor has been fundamental, since he actually drafted the legislative decree on social security safety nets (Italian Legislative Decree no. 148/2015).Footnote 2 Sacchi was initially contacted, on behalf of Matteo Renzi, by Marianna Madia, who was in charge of the labour market portfolio within the National Secretariat of the PD when Renzi became the party’s national secretary (December 2013). Sacchi was given complete free rein in terms of his policy mandate: nobody gave him specific recommendations or set particular policy goals to be achieved through his legislation. He only had to transpose his previous academic and scientific work into legislative form. This latter aspect is of particular interest, in our opinion, because it represents further confirmation of what has been repeatedly argued in the literature on Matteo Renzi’s leadership style and legislative action: that he has been much more interested in changing and renewing policies than in how to actually change and renew them (Capano & Pritoni, 2016).

Once Matteo Renzi had been appointed as Italy’s Prime Minister in February 2014, the need for the Government to present a draft bill on the reform of the Italian labour market became even more pressing. Between February and December 2014, Sacchi worked on his proposal on social security safety nets; throughout this period, he was in daily contact with other policy advisors (Nannicini, Leonardi, Del Conte) and counsellors working on behalf of Prime Minister Renzi, although he never met personally with the Prime Minister. Marianna Madia and Filippo Taddei (who was in charge of the macro-economic portfolio within the National Secretariat of the PD) acted as intermediaries between Sacchi and the Prime Minister. In this sense, the relationship between the policy advisor and Renzi were mediated by other advisors, with whom Sacchi moreover met very frequently and in an informal way.

The final thing that ought to be noted here concerns the professionalisation of advice provision: how was advice remunerated? Was the advisor officially part of the policymaker’s staff? In this regard, Stefano Sacchi’s involvement differs from that seen in our second case study. Indeed, Sacchi worked both formally and informally for the government. During the initial period of his involvement (between February and October 2014), he had no official role either as a policy advisor for the PD or as an advisor to the government. Yet, the Minister of Labour and Social Policies, Mr. Giulio Poletti, appointed him as an official counsellor to his Ministry in November 2014. Sacchi held this office for more than one year, up to end of 2015, when the government decided to appoint him as the President of INAPP—Istituto Nazionale per l’Analisi delle Politiche Pubbliche (National Institute for Public Policy Analysis). In other words, his advice had been highly appreciated and consequently duly remunerated.

During the same period of the labour market reform, Renzi directly contacted another political scientist and recognised columnist of op-eds, Roberto D’Alimonte (full professor at the LUISS Guido Carli University in Rome), to ask him to draft a new electoral law that would have been approved by the main opposition party, Forza Italia, led by Silvio Berlusconi.Footnote 3 The electoral reform was considered to be part of the informal bipartisan agreement also known as ‘il Patto del Nazareno’, the pact named after the national headquarters of the PD in Rome, where Renzi and Berlusconi had met in January 2014 to discuss potential institutional reforms (Parisi, 2015). Significantly, several technical aspects of the new electoral law as one of many features of the Patto del Nazareno had been discussed in advance by Renzi and D’Alimonte (as his key advisor on this subject) starting in late December 2013.

In a nutshell, the first draft bill was built around a two-round electoral system based on party-list proportional representation, with a majority prize and a 3% access threshold. D’Alimonte’s advice was fairly technical and focused on the functioning of different electoral systems in terms of proportionality and governability. In particular, the content of D’Alimonte’s advice was aimed at introducing the double-round system as a means by which to counter party fragmentation.Footnote 4 Significantly, with the help of his team of young political science researchers based at the CISE Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali (Italian Centre for Electoral Studies), affiliated to the University of Florence and to the LUISS University in Rome, D’Alimonte only worked with Renzi on the drafting of the very first version of the reform bill (which included the two rounds, lower access thresholds and majority prize to coalitions and not to party lists, as in the final version) between late December 2013 and March 2014, after which he was no longer consulted by Renzi on this matter. After the failure of the 2016 constitutional reform bill, the Italicum was shelved, and neither D’Alimonte nor any other political scientist was involved in the redrafting of the present electoral law.

In this specific case, D’Alimonte was directly engaged as advisor on the reform by Renzi, but this engagement was never formalised, and D’Alimonte was never remunerated for his efforts. There were both professional and personal reasons for D’Alimonte’s involvement. In fact, D’Alimonte is widely acknowledged as one of the main experts on electoral systems in Italy. He is active in public debate through the columns he writes for the main Italian financial journal (il Sole 24 Ore), and he does not have any party ties or political affiliations. D’Alimonte was also personally known to Renzi—who initially followed him as columnist of the Sole 24 Ore and through his frequent TV appearances—and starting from 2012, Renzi invited him to speak at Renzi’s political annual event entitled the ‘Leopolda’, held in the city of Florence which is where D’Alimonte used to work and currently lives. The ‘Professor’—as Renzi used to call him—was also known to other political leaders such as Denis Verdini—who actually discussed several technical aspects of the new electoral system with D’Alimonte. D’Alimonte’s advice was then discussed with other political key actors, also in his presence, with the aim of finding technical solutions for a compromise acceptable to both PD and Forza Italia. At the same time, D’Alimonte offered his point of view in national newspaper op-eds and on TV and also explicitly criticised certain aspects of the latest version of the reform.

According to D’Alimonte, Renzi’s mandate was to draft a proper legislative bill as soon as possible. Renzi himself proved competent in terms of the functioning of the different electoral systems, while welcoming D’Alimonte’s advice only for a limited period of time before discarding some of his recommendations. Informality and a sense of urgency thus shaped this policy advice relationship, with D’Alimonte and his colleagues quickly producing both the very first draft of the bill and the simulations of the functioning of the different electoral systems. In keeping with the characteristics of Italian law-making, it is noticeable that the legislative bill was a key product of the advice given, thus confirming the centrality of the legalist culture among Italian policymakers.

Overall, these two cases highlight two striking things: first of all, both of the political scientists in question had been hired on the basis of their being known to key political actors (and/or their direct co-workers). Even though their professional status as academics was well known, they were not chosen for the reason that they represented political science as an academic discipline. Second, in both cases the relationship between policy advisors and policymakers was very informal: D’Alimonte acted as a direct advisor to the Prime Minister for the entire time, without being assigned any formal role, while Sacchi actually drafted his reform proposal while not being a consultant of the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies. He was appointed after giving his advice, as a reward for his work, not before. Hence, both IPSs were not recruited exclusively for their scientific credibility or their capacity to contribute to evidence-based policymaking, and in turn, their involvement in the policymaking process did not follow professionalised and/or institutionalised patterns. On the one hand, personal knowledge and proximity seem to play a vital role in guiding the demand for policy advice from policymakers and political leaders. On the other hand, advice is given without any remuneration (D’Alimonte) or formal role (Sacchi).

4 Conclusions

The Italian PAS has received scant attention in the literature, and the empirical evidence regarding the role that IPSs play within that system is even more limited. Thanks to an online survey of 177 IPSs and the reconstruction of two particularly relevant policy processes in which IPSs provided valuable advice, this chapter specifically seeks to bridge this gap.

The empirical analysis conducted here can effectively be summarised in the form of three main considerations. First, IPSs seldom engage in policy advisory activities. Many of them have never done so. Yet, those who do are consulted infrequently and in relation to a few specific issues concerning, above all, public administration, electoral systems, international relations, relations with the European Union, immigration and civil rights policies. Second, there are no particular differences—from the point of view of personal characteristics—between those who provide advice and those who, on the contrary, have never done so. Male political scientists provide policy advice to the same extent as their female counterparts do. The same holds true for academics on temporary contracts and more experienced scholars. Third, the advice provided by IPSs is both formal and informal. As the aforementioned two case studies show, however, it is the informal channel that can have the greatest impact on policymaking. This reminds us of how much the Italian PAS is still poorly institutionalised and largely based on personal relationships and political proximity.

Notes

- 1.

Italy had approved (at least) four ‘large-scale’ labour market reforms, representing a paradigmatic policy change, over the course of the previous 25 years: the so-called Pacchetto Treu in 1997, the ‘Biagi Reform’ in 2003, the ‘Fornero Reform’ in 2012, and the Jobs Act in 2014. As for the electoral system, after more than 40 years with the same proportional electoral law, Italy has witnessed a series of reforms: in 1993 (Mattarella Law), in 2005 (the so-called Porcellum, or Calderoli Law), in 2015 (the so-called Italicum), and in 2017 (the law currently in force).

- 2.

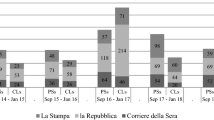

The empirical material for this part of the chapter is taken from newspaper articles published in the main Italian newspapers—Il Corriere della Sera, La Repubblica, il Sole 24 Ore—and from a semi-structured interview (held in June 2017) with Stefano Sacchi, to whom the authors are grateful.

- 3.

The empirical material for this part of the chapter is taken from newspaper articles published by the main Italian newspapers—Il Corriere della Sera, La Repubblica, il Sole 24 Ore—and from a semi-structured interview (held in February 2018) with Roberto D’Alimonte, to whom the authors are grateful.

- 4.

See La Repubblica, Firenze local edition, “D’Alimonte: ‘I miei rapporti con Renzi? Inesistenti’”, March 6, 2014, accessed online February 11, 2019.

References

Blum, S., & Brans, M. (2017). Academic policy analysis and research utilization for policymaking. In M. Brans, I. Geva-May, & M. Howlett (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Comparative Policy Analysis (pp. 341–359). Routledge.

Bouwen, P. (2002). Corporate lobbying in the European Union: the logic of access. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(3), 365–390.

Capano, G., & Gualmini, E. (2011). La pubblica amministrazione in Italia. seconda edizione, Bologna: Il Mulino.

Capano, G., & Vassallo, S. (Eds.). (2003). La dirigenza pubblica. Il mercato e le competenze dei ruoli manageriali. Rubbettino.

Capano, G., & Verzichelli, L. (2016). Looking for eclecticism? Structural and contextual factors underlying political science’s relevance gap: evidence from the Italian case. European Political Science, 15(2), 211–232.

Capano, G., & Pritoni, A. (2016). Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, Who is the Most Reformist One of All? Policy Innovation and Design Coherence of the Renzi Government. Contemporary Italian Politics, 8(3), 289–302.

Chiaramonte, A., Emanuele, V., Maggini, N., & Paparo, A. (2018). Populist Success in a Hung Parliament: The 2018 General Election in Italy. South European Society and Politics, 23(4), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2018.1506513

Craft, J., & Halligan, J. (2017). Assessing 30 years of Westminster policy advisory system experience. Policy Sciences, 50(1), 47–62.

Craft, J., & Howlett, M. (2013). The Dual Dynamics of Policy Advisory Systems: The Impact of Externalization and Politicization on Policy Advice. Policy and Society, 32(3), 187–197.

Craft, J., & Howlett, M. (2012). Policy Formulation, Governance Shifts and Policy Influence: Location and Content in Policy Advisory Systems. Journal of Public Policy, 32(2), 79–98.

Cattaneo, M. C. (2018). Prodotti di ricerca e relazioni istituzionali: il «boundary work» del policy advice al livello subnazionale. Rivista Italiana di Politiche Pubbliche., 3, 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1483/91559

Curini, L. (2010). Experts’ Political Preferences and Their Impact on Ideological Bias. Party Politics, 3, 299–321.

Dente, B. (1995). In un diverso stato. Come rifare la pubblica amministrazione italiana. Il Mulino.

Dente, B. (1997). Sub-national governments in the long Italian transition. West European Politics, 20(1), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389708425180

Di Mascio, F., & Natalini, A. (2013). Analysing the role of ministerial cabinets in Italy: Legacy and temporality in the study of administrative reforms. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 79, 328–346.

Di Mascio, F., & Natalini, A. (2016). Ministerial advisers between political change and institutional legacy: The case of Italy. Acta Politica, 5(4), 517–538.

Galanti, M. T., & Lippi, A. (2018). Il policy advice tra relazioni e forme di legittimazione. Rivista Italiana di Politiche Pubbliche, 3, 319–332.

Guaschino, E. (2018). Definire per risolvere? Il ruolo dell’Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA) nelle politiche ambientali. Rivista Italiana di Politiche Pubbliche, 3, 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1483/91558

Halligan, J. (1995). Policy Advice and the Public Sector. In B. G. Peters & D. J. Savoie (Eds.), Governance in a Changing Environment (pp. 138–172). McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Howlett, M. (2009). Policy Analytical Capacity and Evidence-Based Policy-Making: Lessons from Canada. Canadian Public Administration, 52(2), 153–175.

Hustedt, T., & Veit, S. (2017). Policy advisory systems: Change dynamics and sources of variation. Policy Sciences, 50(1), 41–46.

Lippi, A. (2011). Evaluating the ‘Quasi Federalist’ Programme of Decentralisation in Italy since the 1990s: A Side-effect Approach. Local Government Studies, 37(5), 495–516.

Ongaro, E. (2008). L’organizzazione dello Stato tra autonomia e “policy capacity”. Rubbettino editore.

Parisi, M. (2015). Il patto del Nazareno – 18 gennaio 2014 – 31 gennaio 2015. Rubbettino editore.

Piattoni, S. (2016). Lo stile di policy del governo Renzi. Rivista Italiana di Politiche Pubbliche, 11(1), 5–22.

Pritoni, A., & Sacchi, S. (2019). I gruppi di interesse e il «Jobs Act»: lobbying con quali effetti? Rivista Italiana di Politiche Pubbliche, 14(2), 181–212.

Regonini, G. (2017). Governmentalities without policy capacity. Policy Sciences, 50(2), 163–178.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pritoni, A., Galanti, M.T. (2022). Of Pure Academics and Advice Debutants: The Policy Advisory Roles of Political Scientists in Italy. In: Brans, M., Timmermans, A. (eds) The Advisory Roles of Political Scientists in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86004-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86005-9

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)