Abstract

The application of advanced embodied technologies, particularly virtual reality (VR), has been suggested as a means to induce the full-body illusion (FBI). This technology is employed to modify different facets of bodily self-consciousness, which involves the sense of inhabiting a physical form, and is influenced by cognitive inputs, affective factors like body dissatisfaction, individual personality traits and suggestibility. Specifically, VR-based Mirror Exposure Therapies are used for the treatment of anorexia nervosa (AN). This study aims to investigate whether the “Big Five” personality dimensions, suggestibility, body dissatisfaction and/or body mass index can act as predictors for FBI, either directly or acting as a mediator, in young women of similar gender and age as most patients with AN. The FBI of 156 healthy young women immersed in VR environment was induced through visuomotor and visuo-tactile stimulations, and then assessed using the Avatar Embodiment Questionnaire, comprising four dimensions: Appearance, Ownership, Response, and Multi-Sensory. Data analysis encompassed multiple linear regressions and SPSS PROCESS macro’s mediation model. The findings revealed that the “Big Five” personality dimensions did not directly predict FBI in healthy young women, but Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism exerted an indirect influence on some FBI components through the mediation of suggestibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The concept of “bodily self-consciousness” (BSC), defined as the sensation of inhabiting a physical form (Blanke 2012; Lenggenhager et al. 2007; Tsakiris et al. 2007), has been demonstrated to hold a pivotal position in shaping cognition and self-perception. This is because our interaction with the world is mediated through our own body, which serves as a perceptual entity distinct from the surrounding environment (Pyasik et al. 2022). As described in Riva (2016, 2018), BSC is a coherent supramodal representation produced in a body-self neuromatrix, not only from sensory inputs (exteroceptive, interoceptive, proprioceptive), but also through the mediation of cognitive (thoughts, memories, meanings, beliefs, attitudes, values, etc.) and affective inputs (feelings, body satisfaction, etc.). Furthermore, many studies (e.g., Brewin et al. 2010; Melzack 2005; Riva 2014; Riva et al. 2014a, b; Serino and Riva 2014) suggested that different mental health disorders (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder -PTSD-, eating disorders, depression, chronic pain, or even autism, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s) might be related to an altered functioning of the BSC neuromatrix, and especially to abnormal interactions between perceptual (egocentric) and schematic (allocentric) contents coded in the memory. These resultant maladaptive body representations typically remain beyond conscious awareness. Therefore, the suggested approach for their modification involves the creation and reinforcement of alternative representations (Brewin 2006). In pursuit of this objective, the “Body swapping” technique has been introduced as a means to substitute the individual’s actual physical body (i.e., the body initially perceived through the BSC neuromatrix) with synthetic counterparts, thereby engendering an illusory sense of ownership over a virtual body (referred to as an “avatar”). This approach has been advocated for application among both clinical and non-clinical populations (Serino et al. 2016, 2019).

The notion of embodiment typically encompasses three key dimensions: self-location (indicating the feeling of being situated within the avatar’s body), body ownership (representing the sensation of possessing the virtual body), and agency (denoting the sense of control over the avatar and its influence on the virtual environment) (Kilteni et al. 2012). Both the realms of “embodiment science” and the full body illusion (FBI) paradigm, inspired by the principles of the rubber hand illusion (RHI), which entails experimentally induced illusory ownership over a synthetic or virtual body, serve as principal conceptual frameworks aimed at comprehending the impact of self-avatars on their users (Furlan and Spagnolli 2021; Kilteni et al. 2012; Maselli and Slater 2013; Petkova et al. 2011; Spanlang et al. 2014). Their therapeutic application has demonstrated enhancements in users’ cognitive abilities (Steed et al. 2016), haptic performance (Maselli et al. 2016), and self-recognition/identification (Gonzalez-Franco et al. 2020). Within this context, advanced technologies are being explored for the purpose of modifying (e.g., structuring, augmenting, or replacing) the attributes of BSC and altering the subjective experience of inhabiting a body. This novel interdisciplinary field, termed “embodied medicine,” has emerged with the objective of enhancing the health and well-being of individuals through such interventions (Riva 2016; Riva et al. 2017, 2019).

Virtual Reality (VR) represents an immersive and embodied technology with the capacity to construct ecologically valid virtual environments. Within these environments, individuals can actively manipulate and explore their surroundings. Furthermore, VR affords the opportunity to create synthetic virtual bodies capable of inducing BSC (Riva et al. 2014a, b). In this way, users can perceive and interact with these avatars as if they were their authentic physical bodies, a phenomenon referred to as “synthetic embodiment” (Moseley et al. 2012; Riva 2016). To achieve this, synchronous visuo-proprioceptive, visuo-motor, and visuo-tactile stimulations can be applied, replicating sensory-motor experiences that encompass visceral/autonomic (interoceptive), motor (proprioceptive), and sensory (e.g., visual, auditory) information. These stimulations effectively reactivate the multimodal BSC neuromatrix (Aspell et al. 2012; Lenggenhager et al. 2007; Pyasik et al. 2022; Riva 2016; Riva et al. 2019). In recent decades, VR has seen extensive utilization in psychological and neurocognitive interventions, a trend well-documented in comprehensive reviews (Matamala-Gomez et al. 2021; Rizzo and Bouchard 2019). The increasing ease of implementation and cost-effectiveness of VR systems have significantly enhanced their efficacy. VR interventions have demonstrated their capacity to influence a wide array of domains, including perception, motor functions, executive functions, and social cognition (Pyasik et al. 2022). Consequently, VR has found application in diverse domains, ranging from motor rehabilitation (Tambone et al. 2021) and the treatment of body image disturbances and eating disorders (Clus et al. 2018; Freeman et al. 2017; Gutiérrez-Maldonado et al. 2016; Gutiérrez-Maldonado and Riva 2021; Magrini et al. 2022; Meschberger-Annweiler et al. 2023; Porras-Garcia et al. 2020; Riva et al. 2021), to the promotion of positive attitudes in social interactions (Banakou et al. 2020; Guegan et al. 2016; Hamilton-Giachritsis et al. 2018; Seinfeld et al. 2018) and the mitigation of negative ones (Bourdin et al. 2017; Gorisse et al. 2021; Guterstam et al. 2015). Its clinical potential has been validated in the diagnosis and treatment of various disorders, and demonstrating long-term effects that extend into real-world settings (Riva et al. 2019).

In recent years, numerous studies have been conducted to identify potential predictors of FBI to detect individuals who may exhibit a greater predisposition or resistance to VR-based therapies that involve synthetic embodiment. These studies have explored both external factors related to the experimental setup or the avatar itself and internal factors, individual differences, dependent on the states and personality traits of the users. For instance, external factors like the synchronicity of visuotactile or visuomotor stimulations (Kokkinara and Slater 2014) and the avatar’s appearance, including coherent clothing and skin tone (Maselli and Slater 2013), have been found to enhance the sense of ownership illusion. Similarly, the sense of presence (Slater and Usoh 1993) has been established as a predictor of FBI (Ventura et al. 2022), and it has been further predicted by various internal factors such as absorption (Kober and Neuper 2012) and empathy (Ling et al. 2013; Nicovich et al. 2005; Sas and O’Hare 2003). This suggests that presence may play a mediating role in the relationship between users’ personality traits and FBI. The locus of control (LoC) has also been shown to influence the sense of presence, although its effects have varied depending on whether it was considered internal or external. For example, both external (Murray et al. 2007) and internal (Wallach et al. 2010) LoC have been found to enhance the sense of presence in different studies. Additionally, recent research (Dewez et al. 2019; Jeunet et al. 2018) has indicated that the “agency” component of FBI is linked to internal LoC, while the “ownership” component is positively correlated with external LoC. Furthermore, electrophysiological measures (Alchalabi et al. 2019; González-Franco et al. 2014) have yielded new insights, including positive correlations between biomarkers and FBI. For instance, highly embodied individuals exhibited 400N amplitudes in the parietal cortex when they lost agency over their virtual bodies (Padrao et al. 2016; Pavone et al. 2016), and stronger P300 responses were detected when their virtual avatars were threatened (González-Franco et al. 2014). However, most studies focusing on individual differences as potential predictors have primarily examined the RHI within the physical realm. Higher responses to the RHI have been observed in individuals with traits such as Novelty Seeking or Psychoticism (Kállai et al. 2015), as well as in individuals with personality or psychotic disorders, including the dissociative subtype of PTSD (Rabellino et al. 2016), schizophrenia (Peled et al. 2000; Thakkar et al. 2011), and schizotypal personality disorder (Asai et al. 2011; Van Doorn et al. 2018), as well as empathic individuals (Asai et al. 2011; Seiryte and Rusconi 2015). In summary, FBI is influenced by numerous factors, both internal and external, each of which explains only a small percentage of its variability. Therefore, further research, such as the present study, is essential to enhance predictive models of FBI by considering additional variables.

As previously noted, cognitive and affective inputs, acquired through prior experiences and encoded in memory, play a mediating role in the formation of the supramodal representation of BSC. Consequently, personality traits (defined as sets of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors characterizing an individual consistently and over time) and body dissatisfaction (BD) as a trait (representing the affective dimension of body image disturbances) hold particular significance in the exploration for potential predictors of the full-body illusion. Several studies have utilized the “Big Five” model, which includes five dimensions: Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism, in investigating interpersonal differences as potential predictors of the FBI. For instance, Openness, Extraversion, and Neuroticism have exhibited positive correlations with immersive tendencies, subsequently contributing to the sensation of presence (Ling et al. 2013; Weibel et al. 2010). Moreover, Agreeableness has demonstrated a positive correlation with spatial presence (Sacau et al. 2005). However, it is worth noting that results have at times presented contradictions. For instance, research has shown both positive (Laarni et al. 2004) and negative (Jurnet et al. 2005) correlations between extraversion and the sense of presence. Additionally, some authors have suggested that the Big Five personality dimensions may not constitute the primary factors influencing FBI (e.g., Dewez et al. 2019). With respect to BD as a trait, a number of studies (Corno et al. 2018; Monthuy-Blanc et al. 2020) have revealed that BD serves as a predictor of perceptual body distortion when viewed from an allocentric perspective (i.e., third-person view). This distortion refers to external body benchmarks that are constructed through inter-individual comparisons and are influenced by abstract knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes related to a person’s body within a given cultural context. Consequently, BD is more likely to exert an influence on the “ownership” and “appearance” dimensions of the FBI, from this perspective. Conversely, when considering BD from an egocentric perspective (i.e., first-person view), it becomes more closely associated with real-time perception-driven inputs, and thus, is more likely to impact the “self-location,“ “agency,“ or “multi-sensory” dimensions of FBI.

Moreover, since previous research has highlighted that body representations and BD factors, which may serve as predictors for FBI, are influenced by social comparison within a given cultural context (e.g., thin ideal internalization (Stice et al. 1996), weight bias internalization (Pearl and Puhl 2014), or exposure to social media (Aparicio-Martinez et al. 2019; Perloff 2014), it becomes crucial to consider the cognitive processes that facilitate the impact of societal messages disseminated by the media on body image, particularly suggestibility. Suggestibility is defined as a trait characterized by a tendency to believe and act upon messages without critically evaluating information that might contradict their accuracy. Individuals with high suggestibility readily accept information without engaging in critical thought or questioning its veracity (Kotov et al. 2004). Consequently, they can be more susceptible to the influence of sociocultural messages promoting the thin ideal (e.g., Mask and Blanchard 2011). For instance, higher levels of suggestibility have been associated with poorer body image (Fadul et al. 2022). However, to date, only a limited number of studies have explored the relationship between suggestibility and FBI, often focusing solely on hypnotic suggestibility in the context of the RHI, occasionally yielding contradictory findings. While Lush et al. (2020) argued that RHI was only induced through imaginative suggestion, this conclusion was subsequently reevaluated by Ehrsson et al. (2022), who found no significant relationship between hypnotic suggestibility and RHI. Furthermore, Walsh et al. (2015) identified a positive correlation between hypnotic suggestibility and implicit RHI (though not with explicit RHI) and postulated that suggestibility might facilitate the multisensory integration of visuo-proprioceptive inputs, leading to greater perceptual mislocalization of the participant’s hand through attentional mechanisms. Additionally, a recent study by Forster et al. (2022) showed that FBI ownership ratings were positively affected by suggestibility. However, the fact that the sample of this last study included both female and male participants may limit the interpretation of these results for a specific gender, since Gonzalez-Ordi and Miguel-Tobal (1999) indicated that suggestibility scores higher in women than men.

In a similar way as for suggestibility, gender and age can also exert an influence on other variables considered in this study, such as personality traits and BD. Indeed, previous research has indicated that women score significantly higher in Neuroticism and Agreeableness than men (Costa et al. 2001; Kajonius and Johnson 2018; McCrae and Terracciano 2005; Schmitt et al. 2008; Weisberg et al. 2011). Furthermore, young people score more in Neuroticism, Extraversion and Openness to experience, and less in Agreeableness and Conscientiousness than older people (Anusic et al. 2012; Donnellan and Lucas 2008; Lucas and Donnellan 2009; Roberts and Walton 2006; Soto et al. 2011). Additionally, previous studies have demonstrated that women reported much higher BD than men, and that BD was assessed, perceived, or managed differently across various life stages, including childhood, adolescence, early and mid-adulthood (Bully and Elosua 2011; Esnaola et al. 2010; McLean et al. 2022). This may be an issue for researchers and clinicians who may use these results to get a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that influence FBI elicitation, with the aim of designing specific VR-based therapies for patients of a specific gender or age. This is usually the case for the VR-based Mirror Exposure Therapies (VR-MET) used for the treatment of anorexia nervosa (AN) (e.g., Riva et al. 2021; Porras-Garcia et al. 2021), mainly diagnosed in young women. Indeed, the lifetime prevalence rates of AN might be up to 4% among females and only 0.3% among males, and the pooled incidence rates were shown to be higher for females aged 10–29 years, both in outpatient healthcare services and in hospital admissions (Martinez-Gonzalez et al. 2020; Van Eeden et al. 2021). On the other hand, most of the studies mentioned hereabove focused on the direct effect of personality traits, suggestibility and/or BD on FBI. However, it is likely that the mechanism influencing FBI is more complex and involves variables that do not directly predict FBI but do so through the mediation of other variables.

Consequently, the primary aim of the present study was to investigate whether the “Big Five” personality dimensions, suggestibility and/or other variables related to AN symptomatology (body dissatisfaction and body mass index -BMI-) could predict FBI and/or its constituent components, not only directly but also through the mediation of others of the variables considered. For this purpose, PROCESS macro v.4.1 (Hayes 2022) mediation analyses were used, and only young female participants, with gender and age characteristics similar to the most prevalent AN population, were included in order to avoid gender and age biases. This inquiry sought to determine whether these variables might underlie a predisposition or resistance to the VR-MET used in the treatment of AN, and specifically, whether any of the variables considered acted as significant mediators within the resulting predictive model.

2 Material and method

2.1 Participants

One hundred sixty-nine female college students were recruited using social networks and flyers to voluntarily participate in this study. The exclusion criteria encompassed self-reported severe mental disorders characterized by psychotic or manic symptoms (e.g., psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, etc.), eating disorders and pregnancy (as it could potentially transiently impact body image perception and self-assessment), and sensory impairments that could impede exposure (e.g., visual, tactile, or auditory deficits). Thirteen volunteers, who met at least one of these criteria, were excluded from the study. Finally, one hundred fifty-six female college students (Mage = 24.21 years, SDage = 3.42 years) participated in the study.

2.2 Instruments

The participants were immersed in a VR environment using a head-mounted display (HMD) HTC VIVE Pro Eye™ (HTC Corporation, Taoyuan, Taiwan), including dual-OLED displays with a combined resolution of 2880 × 1600 pixels and 615 PPI. Five trackers, one in the HMD, two in the VR controllers participants held, and two in the feet, were utilized to facilitate real-time replication of participant movements onto their avatars. The VR environment consisted of a room, designed using Unity 3D 5.6.1. (Unity Technologies, San Francisco, CA, USA), without any furniture except for a large mirror located one meter and a half in front of the participants and two boxes placed on the floor beside them (see Fig. 1a). Initially, generic male and female avatars of Caucasian ethnicity were created within Blender v. 2.78 software. These avatars were dressed in standard attire, comprising a t-shirt, trousers, and shoes. Subsequently, they were tailored to match the unique physique of each participant using a photographic adjustment process. The color of the avatar’s clothing and its skin tone were customizable to align with that of the participant. Additionally, the avatar wore sunglasses (that simulated the HMD), and its head was covered by a grey cap, to reproduce the actual participant’s condition during the task and to reduce the influence of individual hairstyles. Finally, the participants could see their virtual body (i.e., their avatar) both from allocentric perspective (e.g., looking at the virtual body in the virtual mirror; see Fig. 1b), and from egocentric perspective (e.g., moving their virtual arms in front of their eyes or looking down at their virtual feet; see Fig. 1c). Allowing participants the simultaneous capability to observe their avatars within the VR environment from both egocentric and allocentric perspectives has been demonstrated to evoke heightened sensations of avatar ownership, amplified physiological responses, and a more comprehensive experience of the peripersonal space. This dual perspective facilitates the updating of central body representations, as supported by prior research (Preston et al. 2015).

2.3 Measures

Participant’s weight and height were measured on-site. Then, Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated using the formula: BMI = weight (in kg)/ height (in m)2.

The assessment of personality traits, commonly referred to as the “Big Five” (comprising Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism), was conducted using the Spanish version of the self-reported mini-IPIP questionnaire, employing positive wording (Martínez-Molina and Arias 2018). In this positively worded questionnaire, it is important to note that the items contributing to the “Neuroticism” subscale were elaborated with a positive semantic polarity towards “Emotional stability” instead of “Neuroticism” (Martínez-Molina and Arias 2018). This questionnaire employed a 20-item 5-point Likert scale (Donnellan et al. 2006). As reported in Donnellan et al. (2006), the average reliabilities indices (Cronbach’s alpha) of the original English version were 0.81 (Extraversion), 0.73 (Agreeableness), 0.70 (Conscientiousness), 0.74 (Neuroticism) and 0.69 (Openness). Additionally, correlation and fit indices provided further support for the construct, convergent, and discriminant validity. Regarding the Spanish version with positive wording, a study with native Spanish speakers (Martínez-Molina and Arias 2018) demonstrated good convergent validity with the English original version with Pearson’s correlations from 0.87 (Emotional stability) to 0.94 (Extraversion), and good reliability with Cronbach’s α from 0.69 (Emotional stability) to 0.95 (Agreeableness). The Cronbach’s α calculated from the data of the present study were the following: 0.82 (Extraversion), 0.70 (Agreeableness), 0.81 (Conscientiousness), 0.66 (Emotional stability), 0.75 (Openness).

Suggestibility was assessed using the self-reported 22-item 5-point Likert scale Suggestibility Inventory (Gonzalez-Ordi and Miguel-Tobal 1999), which demonstrated good psychometric properties: good internal consistency (αCronbach = 0.79), and stability over time (3-month test–retest reliability: r = 0.70) (Gonzalez-Ordi and Miguel-Tobal 1999). The Cronbach’s α calculated from the data of the present study was 0.78.

The Spanish version (Elosua et al. 2010) of EDI-3 inventory (Garner 2004) was used to assess BD as a trait. The EDI-3 is a self-reported 91-item 6-point Likert scale inventory, including 12 subscales. Only the 10-item BD scale (EDI-BD) was used in the present study, since this subscale specifically evaluates BD with the whole body and specific body parts. The Spanish version of this scale has shown robust validity indices, good internal consistency (αCronbach ranging from 74 to 0.96) and temporal stability (good two-week test–retest reliability: r = 0.86) (Elosua et al. 2010; Elosua and López-Jáuregui 2012). The Cronbach’s α calculated from the data of the present study was 0.84.

FBI was assessed using the Avatar Embodiment Questionnaire (AEQ; Peck and Gonzalez-Franco 2021), a self-reported 16-item 7-point Likert scale inventory, including four components: Appearance (FBI_App), Ownership (FBI_Own), Response (FBI_Resp) and Multi-Sensory (FBI_MS). Each of these components exhibited high reliability, with Cronbach’s α values as follows:0.79 (Appearance), 0.82 (Response),0.76 (Ownership), and.72 (Multi-Sensory) (Peck and Gonzalez-Franco 2021). The FBI overall index is determined as the arithmetic mean of these four components. The Cronbach’s α, calculated from the data of the present study, were the following: 0.83 (overall FBI index), 0.73 (FBI_App), 0.72 (FBI_Resp), 0.71 (FBI_Own), 0.73 (FBI_MS).

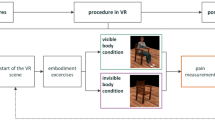

2.4 Procedure

Before the start of the study, each participant was queried about the exclusion criteria and voluntarily provided their signature on a consent form. The consent form detailed the voluntary nature of participation, the confidentiality of data, and the option to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any repercussions. The study procedure was thoroughly explained, and any queries or concerns from participants were duly addressed. To uphold confidentiality, a distinct identification code was assigned to each participant. After measuring participants’ height and weight on-site to calculate BMI, the procedure for creating the virtual body, immersing participants in the virtual environment, incorporating the full-body tracking functionality, and inducing the FBI was derived from previous research (see complete details in Porras-Garcia et al. 2020, 2021). Two photographs of the participant were captured, encompassing both frontal and lateral perspectives, in order to construct an avatar closely resembling the participant’s physique. This involved adjusting various body parts, including shoulders, arms, chest, waist, stomach, hips, thighs, and legs, to align with the images (see Fig. 2a). While the researcher worked on creating the avatar, participants completed the EDI-BD, Suggestibility Inventory, and mini-IPIP scales on a separate computer. The participants were then immersed in the VR environment, using the HTC VIVE Pro Eye™. Additionally, they were equipped with two hand-held controllers and two feet trackers to enable full-body tracking. Next, visuomotor and visuo-tactile stimulation procedures were applied to elicit the FBI. The visuomotor stimulation consisted of a structured series of movements, synchronized between the real and virtual bodies (see Fig. 2b). Regarding the visuo-tactile stimulation, the researcher touched different areas of the participants’ real bodies (i.e., shoulders, arms, legs, stomach) with an HTC-VIVE controller, so that the participants could simultaneously feel the contact of this controller on their real bodies, and see how their avatars were touched by a virtual controller in the same areas and at the same time in the VR environment (see Fig. 2c). Each stimulation lasted about 5 min and could be experienced from both an allocentric perspective (third-person view, looking at their avatars in the mirror) and an egocentric perspective (first-person view, gazing directly at their virtual bodies).

Finally, the FBI experienced by the participants at that moment was assessed through the AEQ scale, whose questions were projected on a blackboard adjacent to the virtual mirror within the VR environment. This setup allowed participants to select their response using one of the handheld controllers as a pointer, all while maintaining the ability to view their virtual bodies from both allocentric and egocentric perspectives. (see Fig. 3).

2.5 Statistical analysis

All the analyses in this study were performed using SPSS v.27 (IBM Company, Armonk, NY, USA).

2.6 Prospective analysis

As an initial step, stepwise multiple linear regressions were carried out to identify predictors of the FBI and its four components (FBI_App, FBI_Own, FBI_Resp, and FBI_MS) among the other variables under consideration, which included the Big Five personality dimensions (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Emotional stability), Suggestibility, BMI and BD. Based on the results of these initial analyses, a second step involved additional stepwise multiple linear regressions. In this phase, the predictors identified in the previous step were treated as the predicted variables, while the remaining variables were considered as potential predictors. During this stage of the analysis, some outliers were identified in the stepwise multiple linear regressions. The criterion for detecting outliers was set at ± 3 standard deviations. After removing these outliers from the respective analyses, the assumptions for linear regression were assessed and found to be satisfied (see Results for details).

The following aspects were checked:

-

Linear Relationships Scatter plots demonstrated apparent linear relationships among the variables.

-

Homoscedasticity The residuals exhibited homoscedasticity, meaning there was uniform variation of the residuals with predicted values. This was indicated by non-significant Pearson correlations (p > 0.05 for all variables).

-

Multicollinearity There was no multicollinearity observed between the considered variables, with tolerance values greater than 0.1 and VIF values less than 10 for all variables.

-

Independence of Residuals The residuals were found to be independent, as assessed by Durbin–Watson statistics, which fell between 1.5 and 2.5 for all analyses.

-

Normality of Residuals Except for the regression analysis with FBI_Own as the predicted variable, where non-compliance with normality was detected, the residuals exhibited normality. This was indicated by non-significant bilateral asymptotic significance in the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p > 0.05 for all variables). For the analysis with FBI_Own as the predicted variable, this non-compliance was addressed in subsequent mediation analysis using the bootstrapping technique, as explained below.

For each analysis, the overall significance of the regression model was confirmed by the ANOVA F-statistic (and its associated p-value) provided by SPSS multiple linear regression function, which is a ratio of the mean square regression to the mean square error.

2.7 Mediation analysis

Subsequent to identifying the predictors of the Full-Body Illusion (FBI) and its components in the initial phase, mediation analyses were conducted using model 4 (simple mediation; see Fig. 4) of the PROCESS macro v.4.1 (Hayes 2022). These analyses were performed for each identified “pathway” X → M → Y, where Y represented FBI or its components as dependent variables, and X and M represented the other variables under consideration (personality, suggestibility, BMI, or BD) as independent variables or mediators.

Mediation model (PROCESS model 4). Note. Model 4 based on p. 622 in Hayes (2022). X, predictor; Mi, moderator(s); Y, dependent variable. a, regression coefficient X → Mi; b, regression coefficient Mi → Y; c’, regression coefficient X → Y (direct effect); c, regression coefficient X → Y (total effect)

Given that the study’s sample size exceeded 50 participants and to provide more robust estimates of standard error (Li et al. 2012), the bootstrap technique was applied in all mediation analyses with 10,000 samples, corresponding to a 99% bootstrap confidence interval (see pp. 103–104 in Hayes 2022). To ensure the reproducibility of results, the bootstrapping SEED was set to 1000.

As per the bootstrap method, an indirect effect is considered statistically significant if the value 0 falls outside the confidence interval (in this case, the CI is set at 95%). Conversely, when the value 0 is encompassed within the CI, the indirect effect is deemed not significant, indicating no significant association between the considered variables. In situations where the 95% confidence intervals for the direct and total effects are not significant (i.e., the value 0 is included within the interval), and only the confidence interval for the indirect effect is significant, it is possible to conclude that the relationship between X and Y is significantly mediated by M.

The regression assumptions for the mediation model were confirmed to be satisfied for each analysis, as they had been previously checked during the initial prospective stage mentioned earlier. Concerning the mediation analyses with FBI_Own as dependent variable, it is worth noting that even though the normality of residuals with FBI_Own as the predicted variable was not met in this specific analysis, normality of residuals could be assumed. This assumption was reasonable because the bootstrap technique was employed with 10,000 samples, which provides more robust estimates of the standard error (for more details, see Li et al. 2012, and pp. 72–73 in Hayes 2022).

3 Results

The descriptive statistics of the complete sample (N = 156) are given in Table 1.

3.1 Prospective analysis

Multiple linear regression analyses showed that only suggestibility predicted FBI, in a model that accounted for 8.4% of the explained variability (two outliers were removed, and a significant linear relation was confirmed by ANOVA: p < 0.001, F(1,152) = 13.930).

Concerning the components of the FBI, the analysis revealed that FBI_App was predicted by Suggestibility, in a model that accounted for 9.8% of the explained variability (one outlier was excluded, and a significant linear relationship was confirmed by ANOVA: p < 0.001, F(1,153) = 16.618). Furthermore, FBI_Resp was predicted by Suggestibility, within a model that explained 10.0% of the explained variability (no outliers were detected, and a significant linear relationship was confirmed by ANOVA with p < 0.001, F(1,154) = 17.088). Additionally, only Suggestibility predicted FBI_Own in a model that explained 3.2% of its variability (no outliers were detected, and a significant linear relationship was confirmed by ANOVA with p = 0.026, F(1,154) = 5.070). Finally, following the removal of the four detected outliers, no variable was identified as a significant predictor of FBI_MS.

As a second step, Suggestibility, as the unique predictor found above, was introduced as predicted variable in new stepwise multiple linear regression, entering the remaining variables as possible predictors. Results showed that Openness, Agreeableness and Emotional stability predicted Suggestibility, in a model that accounted for 24.8% of the explained variability (no outlier was detected, significant linear relation confirmed by ANOVA: p < 0.001, F(3,152) = 16.735).

The significant predictors of FBI and its components, revealed in the prospective phase through multiple linear regressions, can be visualized on the synthesis scheme presented on Fig. 5.

3.2 Mediation analysis

From the results of the prospective stage (see Fig. 5), mediation analysis were conducted using model 4 (see Fig. 4) for every detected “pathway” X → M → Y, that includes three variables: from initial predictors (X = Openness, Agreeableness, and Emotional stability), to FBI or its components (Y = FBI, FBI_App, FBI_Resp and FBI_Own), through the unique possible mediator M = Suggestibility.

The results of all the mediation analysis performed are indicated in Table 2.

All the analyses indicated that the associations between X and Y variables under consideration were significantly mediated by M (the indirect effect’s 95% confidence interval did not include the value 0). A synthesis of these results can be visualized in Fig. 6.

Predictors of FBI – mediation analysis: synthesis scheme. Note. a Predictors and mediators of FBI; b Predictors and mediators of FBI’s components. a, regression coefficient X → M; b, regression coefficient M → Y. Significance level: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Only significant coefficients, with greater significance (lower p) and greater sample size (after removing outliers), are represented here

4 Discussion

The results of this study showed that the Big Five personality dimensions did not have a direct, significant predictive effect on FBI. However, some of these traits (specifically, Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Emotional stability) exerted a significant influence on FBI overall index and three of its components (Response, Ownership and Appearance) through the mediation of suggestibility. On the other hand, none of the variables considered predicted the FBI’s Multisensory component. Overall, these results confirm the positive correlations of Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (i.e., reverse scoring than Emotional stability) with greater immersive tendency and sense of presence found in previous studies (Ling et al. 2013; Sacau et al. 2005; Weibel et al. 2010). In addition, Extraversion and Conscientiousness did not predict FBI (neither directly nor mediated by another variable). These results confirm the lack of prediction ability of Extraversion on FBI, found to be contradictory in previous research (negative correlation with sense of presence found in Jurnet et al. 2005, but positive correlations with immersive tendency and sense of presence found in Ling et al. 2013, Sacau et al. 2005, and Weibel et al. 2010). Regarding suggestibility as a mediator, the positive influence of greater suggestibility on FBI appear to be in tune with the results presented in Forster et al. (2022) and Lush et al. (2020) and Walsh et al. (2015) about RHI (but not with the revised version of Lush et al. (2020) presented in Ehrsson et al. (2022), although the interpretation that was given by these last authors (i.e., facilitation of multisensory integration of visuo-perceptive inputs by suggestibility), cannot be confirmed in our study, since suggestibility did not predict significantly the FBI’s multisensory component. As for the body dissatisfaction and body mass index, our results did not show any influence of BD or BMI on FBI overall index or its components. Specifically, BD did not predict the FBI Ownership component, as hypothesized in Corno et al. (2018) and Monthuy-Blanc et al. (2020).

Overall, the present study’s results support the assertion that the Big Five personality traits do not seem to be the primary factors driving FBI, as suggested in prior research (Dewez et al. 2019). Indeed, the regression models in this study accounted for a relatively low percentage of the explained variability in FBI or its components, typically less than 10%. This suggests that the predictive model presented in this study remains limited, emphasizing the need for future research to gain a better understanding of the factors that may influence and predict FBI. Previous studies have already highlighted the intricate nature of FBI components, their interactions with each other, and the challenges associated with predicting them based solely on personality traits (Dewez et al. 2019; Peck and Gonzalez-Franco 2021).

However, it is important to note that the study’s sample only included young female participants, with gender and age characteristics similar to the most prevalent AN population, in order to avoid gender and age biases. As previously indicated, age and gender can exert an influence both on FBI scores and on the predictors considered in this study, such as personality traits, suggestibity and BD. For instance, participant age has been demonstrated to influence FBI components. Participants over the age of 30 exhibited significantly lower scores on Appearance, Ownership, and Multi-Sensory sub-scales compared to those under 30 (Peck and Gonzalez-Franco 2021). Additionally, the FBI seemed to affect body perception in participants aged 19 to 25 but not in those aged 26 to 55 (Serino et al. 2018), which might be attributed to a more stable body representation in older individuals (Serino et al. 2018). Since significant inter-individual differences can lead to substantial variability in embodiment scores, even when following the same procedure, it becomes necessary to evaluate more diverse samples in order to mitigate potential research biases (Peck and Gonzalez-Franco 2021). In addition, the present study only included healthy participants without self-reported diagnosed mental health disorders that may also impact embodiment scores. Indeed, individuals suffering from personality or psychotic disorders, such as the dissociative subtype of PTSD (Rabellino et al. 2016), schizophrenia (Peled et al. 2000; Thakkar et al. 2011), and schizotypal personality disorder (Asai et al. 2011; Van Doorn et al. 2018), have reported heightened responses to the RHI. Consequently, although this study provides first evidence on a possible predictive mediation model of FBI in healthy young women, which can be considered as a starting point for future research with young female patients with AN, these results should not be generalized to another population with different gender, age, or mental health diagnosis.

Furthermore, there are potential areas for improvement in the procedure for future research. First, the incorporation of 3D body scanning technology, which allows the creation of an exact 3D biometric avatar with all the individual’s characteristics (including age, skin tone, etc.), would significantly enhance the realism of VR embodiment-based techniques compared to the generic avatar generated from photographs used in the current study. Indeed, previous research has shown that the visual appearance and age of the avatar can significantly impact both the response and ownership dimensions of FBI, particularly for participants over the age of 30 (Ebrahimi et al. 2018; Peck and Gonzalez-Franco 2021). Secondly, improvements can be made to visuo-tactile stimulation by employing either affective (e.g., slow stroking velocity at 3 cm/s) or non-affective (e.g., fast stroking velocity at 30 cm/s) touches with the VR controller. Participants have reported a greater sense of ownership over a virtual body in conditions involving affective touch (de Jong et al. 2017). In the present study, although not explicitly specified in the procedure, visuo-tactile stimulation was typically conducted using non-affective touches. Lastly, since inner signals (e.g., interoceptive, proprioceptive, or vestibular signals) also play a role in simulating a complete synthetic multisensory experience, incorporating interoceptive stimulations could be considered to modulate the body experience. For instance, “sonoception,” which involves using wearable acoustic and vibrotactile transducers to alter internal bodily signals (e.g., enhancing heart rate variability by modulating the subjects’ parasympathetic system), could be integrated into the procedure (e.g., as seen in Di Lernia et al. 2018).

To conclude, these study’s results highlight the fact that the “Big Five” personality traits do not directly predict the FBI, but some of them (specifically, Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism) influence FBI components through the mediation of suggestibility in healthy young women. This study also emphasizes the intricate nature of FBI components, their interactions with each other, and the challenges associated with predicting FBI based solely on personality traits, suggestibility, or other body image related variables like body dissatisfaction and body mass index. Based on a sample of young women of similar gender and age as most patients diagnosed with AN, these results cannot be generalized to another population but can be useful to inspire future research that aims to gain a better understanding of how personality traits and suggestibility may influence FBI. Although results should still be confirmed in future study with AN patients, such evidences enable a better understanding of the factors that can lead to either a predisposition or resistance in modifying aspects of bodily self-awareness, such as its structure, augmentation, or replacement, and thus the identification of the patients with AN who are more likely to benefit from VR-MET therapies. Such knowledge is of special interest, since VR, as an immersive and transformative technology, has become more accessible and efficient over the past decade, owing to the widespread availability of affordable and user-friendly VR platforms. Consequently, it will play a pivotal role in advancing embodied medicine as a burgeoning transdisciplinary research field aimed at enhancing people’s health and overall well-being.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Alchalabi B, Faubert J, Labbe DR (2019) EEG can be used to measure embodiment when controlling a walking self-avatar. In: 26th IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces, VR 2019 – Proceedings, pp 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1109/VR.2019.8798263

Anusic I, Lucas RE, Donnellan MB (2012) Cross-sectional age differences in personality: evidence from nationally representative samples from Switzerland and the United States. J Res Pers 46(1):116–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.11.002

Aparicio-Martinez P, Perea-Moreno AJ, Martinez-Jimenez MP, Redel-Macías MD, Pagliari C, Vaquero-Abellan M (2019) Social media, thin-ideal, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes: an exploratory analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH16214177

Asai T, Mao Z, Sugimori E, Tanno Y (2011) Rubber hand illusion, empathy, and schizotypal experiences in terms of self-other representations. Conscious Cogn 20(4):1744–1750. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONCOG.2011.02.005

Aspell JE, Lenggenhager B, Blanke O (2012) Multisensory perception and bodily self-consciousness: from out-of-body to inside-body experience. In: Murray MM, Wallace MT (eds) The neural bases of multisensory processes. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 467–481

Banakou D, Beacco A, Neyret S, Blasco-Oliver M, Seinfeld S, Slater M (2020) Virtual body ownership and its consequences for implicit racial bias are dependent on social context. R Soc Open Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSOS.201848

Blanke O (2012) Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily self-consciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci 13(8):556–571. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRN3292

Bourdin P, Barberia I, Oliva R, Slater M (2017) A virtual out-of-body experience reduces fear of death. PLoS One 12(1):e0169343. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0169343

Brewin CR (2006) Understanding cognitive behaviour therapy: a retrieval competition account. Behav Res Ther 44(6):765–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2006.02.005

Brewin CR, Gregory JD, Lipton M, Burgess N (2010) Intrusive images in psychological disorders: characteristics, neural mechanisms, and treatment implications. Psychol Rev 117(1):210–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0018113

Bully P, Elosua P (2011) Changes in body dissatisfaction relative to gender and age: the modulating character of BMI. Span J Psychol 14(1):313–322. https://doi.org/10.5209/REV_SJOP.2011.V14.N1.28

Clus D, Larsen ME, Lemey C, Berrouiguet S (2018) The use of virtual reality in patients with eating disorders: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 20(4):1–13. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7898

Corno G, Serino S, Cipresso P, Baños RM, Riva G (2018) Assessing the relationship between attitudinal and perceptual component of body image disturbance using virtual reality. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 21(11):679–686. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2018.0340

Costa PT, Terracciano A, McCrae RR (2001) Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: robust and surprising findings. J Pers Soc Psychol 81:322–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322

de Jong JR, Keizer A, Engel MM, Dijkerman HC (2017) Does affective touch influence the virtual reality full body illusion? Exp Brain Res 235(6):1781–1791. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00221-017-4912-9

Dewez D, Fribourg R, Argelaguet F, Hoyet L, Mestre D, Slater M, Lecuyer A (2019) Influence of personality traits and body awareness on the sense of embodiment in virtual reality. In: Proceedings 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, ISMAR 2019, pp 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISMAR.2019.00-12

Di Lernia D, Cipresso P, Pedroli E, Riva G (2018) Toward an embodied medicine: a portable device with programmable interoceptive stimulation for heart rate variability enhancement. Sensors. https://doi.org/10.3390/S18082469

Donnellan MB, Lucas RE (2008) Age differences in the big five across the life span: evidence from two national samples. Psychol Aging 23(3):558–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012897

Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM, Lucas RE (2006) The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Psychol Assess 18(2):192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192

Ebrahimi E, Hartman LS, Robb A, Pagano CC, Babu SV (2018) Investigating the Effects of Anthropomorphic Fidelity of Self-Avatars on Near Field Depth Perception in Immersive Virtual Environments. In: IEEE Conf Virtual Real 3D User Interfaces, VR 2018 - Proc. 2018, pp 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/VR.2018.8446539

Ehrsson HH, Fotopoulou A, Radziun D, Longo MR, Tsakiris M (2022) No specific relationship between hypnotic suggestibility and the rubber hand illusion. Nat Commun 13(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28177-z

Elosua P, López-Jaúregui A, Sánchez-Sánchez F (2010) EDI-3, Inventario de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria-3, Manual. Tea Ediciones: Madrid, Spain

Elosua P, López-Jáuregui A (2012) Internal structure of the spanish adaptation of the eating disorder inventory-3. Eur J Psychol Assess 28(1):25–31. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/A000087

Esnaola I, Rodríguez A, Goñi A (2010) Body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures: gender and age differences. Salud Ment 33(1):21–29

Fadul YM, Assistance M, Alsanosi A, Hassan Y, Mohammed ZO, Elhaj A (2022) Body image and its relationship to suggestibility for students of Alsalam University. Rashhat-e-Qalam 2(1):44–63. https://doi.org/10.56765/rq.v2i1.51

Forster PP, Karimpur H, Fiehler K (2022) Demand characteristics challenge effects in embodiment and presence. Sci Rep 12(1):14084. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18160-5

Freeman D, Reeve S, Robinson A, Ehlers A, Clark D, Spanlang B, Slater M (2017) Virtual reality in the assessment, understanding, and treatment of mental health disorders. Psychol Med 47(14):2393–2400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171700040X

Furlan M, Spagnolli A (2021) Using an embodiment technique in psychological experiments with virtual reality: a scoping review of the embodiment configurations and their scientific purpose. Open Psychol J 14(1):204–212. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350102114010204

Garner, DM (2004) Eating Disorder Inventory– 3 Professional manual. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources

González-Franco M, Peck TC, Rodríguez-Fornells A, Slater M (2014) A threat to a virtual hand elicits motor cortex activation. Exp Brain Res 232(3):875–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00221-013-3800-1

Gonzalez-Franco M, Steed A, Hoogendyk S, Ofek E (2020) Using facial animation to increase the enfacement illusion and avatar self-identification. IEEE Trans vis Comput Graph 26(5):2023–2029. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2020.2973075

Gonzalez-Ordi H, Miguel-Tobal JJ (1999) Characteristics of suggestibility and its relationship with other psychological variables. An Psicol 15(1):57–75

Gorisse G, Senel G, Banakou D, Beacco A, Oliva R, Freeman D, Slater M (2021) Self-observation of a virtual body-double engaged in social interaction reduces persecutory thoughts. Sci Rep 11(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03373-x

Guegan J, Buisine S, Mantelet F, Maranzana N, Segonds F (2016) Avatar-mediated creativity: when embodying inventors makes engineers more creative. Comput Human Behav 61:165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2016.03.024

Guterstam A, Abdulkarim Z, Ehrsson HH (2015) Illusory ownership of an invisible body reduces autonomic and subjective social anxiety responses. Sci Rep 5(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09831

Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Wiederhold BK, Riva G (2016) Future directions: how virtual reality can further improve the assessment and treatment of eating disorders and obesity. Cyberpsychology, Behav Soc Netw 19(2):148–153. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2015.0412

Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Riva G (2021) Technological Interventions for Eating and Weight Disorders. In: Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-818697-8.00057-1

Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Banakou D, Garcia Quiroga M, Giachritsis C, Slater M (2018) Reducing risk and improving maternal perspective-taking and empathy using virtual embodiment. Sci Rep 8(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21036-2

Hayes AF (2022) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and con- ditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. The Guilford Press, New York

Jeunet C, Albert L, Argelaguet F, Lécuyer A (2018) Do you feel in control? Towards novel approaches to characterise, manipulate and measure the sense of agency in virtual environments. IEEE Trans vis Comput Graph 24(4):1486–1495. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2018.2794598

Jurnet IA, Beciu CC, Maldonado JG (2005) Individual Differences in the Sense of Presence. In: Proceedings of Presence 2005: The 8th International Workshop on Presence, 133–142. https://www.academia.edu/6679871/Individual_Differences_in_the_Sense_of_Presence

Kajonius P, Johnson J (2018) Sex differences in 30 facets of the five factor model of personality in the large public (N = 320,128). Pers Individ Dif 129:126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.026

Kállai J, Hegedüs G, Feldmann Á, Rózsa S, Darnai G, Herold R, Dorn K, Kincses P, Csathó Á, Szolcsányi T (2015) Temperament and psychopathological syndromes specific susceptibility for rubber hand illusion. Psychiatry Res 229(1–2):410–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2015.05.109

Kilteni K, Groten R, Slater M (2012) The Sense of embodiment in virtual reality. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ 21(4):373–387. https://doi.org/10.1162/PRES_A_00124

Kober SE, Neuper C (2012) Personality and presence in virtual reality: Does their relationship depend on the used presence measure? Int J Human-Comput Interact 29(1):13–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2012.668131

Kokkinara E, Slater M (2014) Measuring the effects through time of the influence of visuomotor and visuotactile synchronous stimulation on a virtual body ownership illusion. Perception 43(1):43–58. https://doi.org/10.1068/P7545

Kotov RI, Bellman SB, Watson DB (2004) Multidimensional Iowa Suggestibility Scale (MISS) Brief Manual. https://dspace.sunyconnect.suny.edu/handle/1951/60894

Laarni J, Ravaja N, Saari T, Hartmann T (2004) Personality-Related Differences in Subjective Presence ,pp 88–95. Technical University of Valencia. https://research.aalto.fi/en/publications/personality-related-differences-in-subjective-presence

Lenggenhager B, Tadi T, Metzinger T, Blanke O (2007) Video ergo sum: manipulating bodily self-consciousness. Science 317(5841):1096–1099. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1143439

Li X, Wong W, Lamoureux EL, Wong TY (2012) Are linear regression techniques appropriate for analysis when the dependent (outcome) variable is not normally distributed? Invest Ophthalmol vis Sci 53(6):3082–3083. https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.12-9967

Ling Y, Nefs HT, Brinkman WP, Qu C, Heynderickx (2013) The relationship between individual characteristics and experienced presence. Comput Human Behav 29(4):1519–1530. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2012.12.010

Lucas RE, Donnellan MB (2009) Age differences in personality: evidence from a nationally representative Australian sample. Dev Psychol 45(5):1358–1360. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013914

Lush P, Botan V, Scott RB, Seth AK, Ward J, Dienes Z (2020) Trait phenomenological control predicts experience of mirror synaesthesia and the rubber hand illusion. Nat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-020-18591-6

Magrini M, Curzio O, Tampucci M, Donzelli G, Cori L, Imiotti MC, Maestro S, Moroni D (2022) Anorexia nervosa, body image perception and virtual reality therapeutic applications: state of the art and operational proposal. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 19(5):2533. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19052533

Martinez-Gonzalez L, Fernandez-Villa T, Molina AJ et al (2020) Incidence of anorexia nervosa in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:3824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113824

Martínez-Molina A, Arias VB (2018) Balanced and positively worded personality short-forms: mini-IPIP validity and cross-cultural invariance. PeerJ. https://doi.org/10.7717/PEERJ.5542

Maselli A, Slater M (2013) The building blocks of the full body ownership illusion. Front Hum Neurosci 7:83. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNHUM.2013.00083/BIBTEX

Maselli A, Kilteni K, López-Moliner J, Slater M (2016) The sense of body ownership relaxes temporal constraints for multisensory integration. Sci Rep 6(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30628

Mask L, Blanchard CM (2011) The protective role of general self-determination against ‘thin ideal’ media exposure on women’s body image and eating-related concerns. J Health Psychol 16(3):489–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105310385367

Matamala-Gomez M, Maselli A, Malighetti C, Realdon O, Mantovani F, Riva G (2021) Virtual body ownership illusions for mental health: a narrative review. J Clin Med 10(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM10010139

McCrae RR, Terracciano A (2005) Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: data from 50 cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol 88(3):547–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.547

McLean SA, Rodgers RF, Slater A, Jarman HK, Gordon CS, Paxton SJ (2022) Clinically significant body dissatisfaction: prevalence and association with depressive symptoms in adolescent boys and girls. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31(12):1921–1932. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00787-021-01824-4

Melzack R (2005) Evolution of the neuromatrix theory of pain. The Prithvi Raj lecture: presented at the third World Congress of World Institute of Pain, Barcelona 2004. Pain Pract 5(2):85–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1533-2500.2005.05203.X

Meschberger-Annweiler FA, Ascione M, Porras-Garcia B, Ferrer-Garcia M, Moreno-Sanchez M, Miquel-Nabau H, Serrano-Troncoso E, Carulla-Roig M, Gutierrez-Maldonado J (2023) An attentional bias modification task, through virtual reality and eye-tracking technologies, to enhance the treatment of Anorexia nervosa. J Clin Med 12(6):2185. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM12062185

Monthuy-Blanc J, Bouchard S, Ouellet M, Corno G, Iceta S, Rousseau M (2020) “eLoriCorps immersive body rating scale”: exploring the assessment of body image disturbances from allocentric and egocentric perspectives. J Clin Med 9(9):1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM9092926

Moseley GL, Gallace A, Spence C (2012) Bodily illusions in health and disease: physiological and clinical perspectives and the concept of a cortical ‘body matrix.’ Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36(1):34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2011.03.013

Murray CD, Fox J, Pettifer S (2007) Absorption, dissociation, locus of control and presence in virtual reality. Comput Human Behav 23(3):1347–1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2004.12.010

Nicovich SG, Boller GW, Cornwell TB (2005) Experienced presence within computer-mediated communications: initial explorations on the effects of gender with respect to empathy and immersion. J Comput Commun. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1083-6101.2005.TB00243.X

Padrao G, Gonzalez-Franco M, Sanchez-Vives MV, Slater M, Rodriguez-Fornells A (2016) Violating body movement semantics: Neural signatures of self-generated and external-generated errors. Neuroimage 124:147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2015.08.022

Pavone EF, Tieri G, Rizza G, Tidoni E, Grisoni L, Aglioti SM (2016) Embodying others in immersive virtual reality: electro-cortical signatures of monitoring the errors in the actions of an avatar seen from a first-person perspective. J Neurosci 36(2):268. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0494-15.2016

Pearl RL, Puhl RM (2014) Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image 11(1):89–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BODYIM.2013.09.005

Peck TC, Gonzalez-Franco M (2021) Avatar embodiment. A standardized questionnaire. Front Virtual Real 1:575943. https://doi.org/10.3389/FRVIR.2020.575943

Peled A, Ritsner M, Hirschmann S, Geva AB, Modai I (2000) Touch feel illusion in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry 48(11):1105–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00947-1

Perloff RM (2014) Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles 71(11–12):363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11199-014-0384-6

Petkova VI, Björnsdotter M, Gentile G, Jonsson T, Li TQ, Ehrsson HH (2011) From part- to whole-body ownership in the multisensory brain. Curr Biol 21(13):1118–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CUB.2011.05.022

Porras-Garcia B, Ferrer-Garcia M, Serrano-Troncoso E, Carulla-Roig M, Soto-Usera P, Miquel-Nabau H, Shojaeian N, de la Montaña S-C, Borszewski B, Díaz-Marsá M, Sánchez-Díaz I, Fernández-Aranda F, Gutierrez-Maldonado J (2020) Validity of virtual reality body exposure to elicit fear of gaining weight, body anxiety and body-related attentional bias in patients with Anorexia nervosa. J Clin Med 9(10):3210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103210

Porras-Garcia B, Ferrer-Garcia M, Serrano-Troncoso E, Carulla-Roig M, Soto-Usera P, Miquel-Nabau H, Fernández-Del Castillo Olivares L, Marnet-Fiol R, Santos-Carrasco De LM, Borszewski B, Díaz-Marsá M, Sánchez-Díaz I, Fernández-Aranda F, Gutierrez-Maldonado J (2021) AN-VR-BE: a randomized controlled trial for reducing fear of gaining weight and other eating disorder symptoms in anorexia nervosa through virtual reality-based body exposure. J Clin Med 10(4):682. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040682

Preston C, Kuper-Smith BJ, Ehrsson H (2015) Owning the body in the mirror: the effect of visual perspective and mirror view on the full-body illusion. Sci Rep 5(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18345

Pyasik M, Ciorli T, Pia L (2022) Full body illusion and cognition: a systematic review of the literature. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 143:104926. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2022.104926

Rabellino D, Harricharan S, Frewen PA, Burin D, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA (2016) “I can’t tell whether it’s my hand”: a pilot study of the neurophenomenology of body representation during the rubber hand illusion in trauma-related disorders. Eur J Psychotraumatol. https://doi.org/10.3402/EJPT.V7.32918

Riva G (2014) Out of my real body: cognitive neuroscience meets eating disorders. Front Hum Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNHUM.2014.00236

Riva G (2018) The neuroscience of body memory: from the self through the space to the others. Cortex 104:241–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CORTEX.2017.07.013

Riva G, Gaudio S, Dakanalis A (2014a) I’m in a virtual body: a locked allocentric memory may impair the experience of the body in both obesity and anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 19(1):133–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40519-013-0066-3

Riva G, Waterworth J, Murray D (2014b) Interacting with presence: HCI and the sense of presence in computer-mediated environments. De Gruyter Open Ltd. https://doi.org/10.2478/9783110409697

Riva G, Serino S, Di Lernia D, Pavone EF, Dakanalis A (2017) Embodied medicine: mens sana in corpore virtuale sano. Front Hum Neurosci 11:120. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNHUM.2017.00120

Riva G, Wiederhold BK, Mantovani F (2019) Neuroscience of virtual reality: from virtual exposure to embodied medicine. Behav Soc Netw 22(1):82–96. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2017.29099.GRI

Riva G, Malighetti C, Serino S (2021) Virtual reality in the treatment of eating disorders. Clin Psychol Psychother 28(3):477–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/CPP.2622

Riva G (2016) Embodied medicine: what human-computer confluence can offer to health care. In Human computer confluence: transforming human experience through symbiotic technologies, pp 55–79, De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110471137-004

Rizzo A, Bouchard S (2019) Virtual reality and anxiety disorders treatment: evolution and future perspectives. In: Rizzo A, Bouchard S (eds) Virtual reality for psychological and neurocognitive interventions. Springer, Amsterdam

Roberts BW, Walton KE (2006) Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull 132(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1

Sacau A, Laarni J, Ravaja N, Hartmann T (2005) The impact of personality factors on the experience of spatial presence 143–151. University College London Press. https://researchportal.helsinki.fi/en/publications/the-impact-of-personality-factors-on-the-experience-of-spatial-pr

Sas C, O’Hare GMP (2003) Presence equation: an investigation into cognitive factors underlying presence. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ 12(5):523–537. https://doi.org/10.1162/105474603322761315

Schmitt DP, Realo A, Voracek M, Allik J (2008) Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol 94(1):168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.168

Seinfeld S, Arroyo-Palacios J, Iruretagoyena G, Hortensius R, Zapata LE, Borland D, de Gelder B, Slater M, Sanchez-Vives MV (2018) Offenders become the victim in virtual reality: impact of changing perspective in domestic violence. Sci Rep 8(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19987-7

Seiryte A, Rusconi E (2015) The Empathy Quotient (EQ) predicts perceived strength of bodily illusions and illusion-related sensations of pain. Pers Individ Dif 77:112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2014.12.048

Serino S, Riva G (2014) What is the role of spatial processing in the decline of episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease? The “mental frame syncing” hypothesis. Front Aging Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNAGI.2014.00033

Serino S, Pedroli E, Keizer A, Triberti S, Dakanalis A, Pallavicini F, Chirico A, Riva G (2016) Virtual reality body swapping: a tool for modifying the allocentric memory of the body. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw 19(2):127–133. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2015.0229

Serino S, Scarpina F, Dakanalis A, Keizer A, Pedroli E, Castelnuovo G, Chirico A, Catallo V, Di Lernia D, Riva G (2018) The role of age on multisensory bodily experience: an experimental study with a virtual reality full-body illusion. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw 21(5):304–310. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2017.0674

Serino S, Polli N, Riva G (2019) From avatars to body swapping: the use of virtual reality for assessing and treating body-size distortion in individuals with anorexia. J Clin Psychol 75(2):313–322. https://doi.org/10.1002/JCLP.22724

Slater M, Usoh M (1993) Representations systems, perceptual position, and presence in immersive virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ 2(3):221–233. https://doi.org/10.1162/PRES.1993.2.3.221

Soto CJ, John OP, Gosling SD, Potter J (2011) Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: big five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. J Pers Soc Psychol 100(2):330. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021717

Spanlang B, Normand JM, Borland D, Kilteni K, Giannopoulos E, Pomés A, González-Franco M, Perez-Marcos D, Arroyo-Palacios J, Muncunill XN, Slater M (2014) How to build an embodiment lab: achieving body representation illusions in virtual reality. Front Robot AI 1:111756. https://doi.org/10.3389/FROBT.2014.00009

Steed A, Pan Y, Zisch F, Steptoe W (2016) The impact of a self-avatar on cognitive load in immersive virtual reality. Proc IEEE Virtual Real. https://doi.org/10.1109/VR.2016.7504689

Stice E, Nemeroff C, Shaw HE (1996) Test of the dual pathway model of bulimia nervosa: evidence for dietary restraint and affect regulation mechanisms. J Soc Clin Psychol 15(3):340–363. https://doi.org/10.1521/JSCP.1996.15.3.340

Tambone R, Giachero A, Calati M, Molo MT, Burin D, Pyasik M, Cabria F, Pia L (2021) Using body ownership to modulate the motor system in stroke patients. Psychol Sci 32(5):655–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620975774

Thakkar KN, Nichols HS, McIntosh LG, Park S (2011) Disturbances in body ownership in schizophrenia: evidence from the rubber hand illusion and case study of a spontaneous out-of-body experience. PLoS One 6(10):e27089. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0027089

Tsakiris M, Hesse MD, Boy C, Haggard P, Fink GR (2007) Neural signatures of body ownership: a sensory network for bodily self-consciousness. Cereb Cortex 17(10):2235–2244. https://doi.org/10.1093/CERCOR/BHL131

Van Doorn G, De Foe A, Wood A, Wagstaff D, Hohwy J (2018) Down the rabbit hole: assessing the influence of schizotypy on the experience of the Barbie doll illusion. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 23(5):284–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2018.1495623

Van Eeden AE, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW (2021) Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatry 34(6):515–524. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000739

Ventura S, Miragall M, Cardenas G, Banos RM (2022) Predictors of the sense of embodiment of a female victim of sexual harassment in a male sample through 360-degree video-based virtual reality. Front Hum Neurosci 16:845508. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNHUM.2022.845508

Wallach HS, Safir MP, Samana R (2010) Personality variables and presence. Virtual Real 14:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-009-0124-3

Walsh E, Guilmette DN, Longo MR, Moore JW, Oakley DA, Halligan PW, Mehta MA, Deeley Q (2015) Are You suggesting that’s my hand? The relation between hypnotic suggestibility and the rubber hand illusion. Perception 44(6):709–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0301006615594266

Weibel D, Wissmath B, Mast FW (2010) Immersion in mediated environments: the role of personality traits. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 13(3):251–256. https://doi.org/10.1089/CYBER.2009.0171

Weisberg YJ, DeYoung CG, Hirsh JB (2011) Gender differences in personality across the ten aspects of the big five. Front Psychol 2:11757. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00178

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain). Grant PID2019-108657RB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/ https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033. This study also has the support of “Fundació La Marató de TV3”, Grant 202217-10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.A.-M.A., M.A., B.P.-G., M.-T.M.-M., A.F.-E., J.R.-R., M.F.-G. and J.G.-M. Methodology: F.A.-M.A., M.A., M.-T.M.-M., A.F.-E., J.R.-R., M.F.-G. and J.G.-M. Software: F.A.-M.A., M.A. and B.P.-G. Validation: F.A.-M.A., M.A. and J.G.-M. Formal Analysis: F.A.-M.A., M.A., M.-T.M.-M. and J.R.-R. Investigation: F.A.-M.A., M.A., M.-T.M.-M., J.P.-P. and J.G.-M. Data curation: F.A.-M.A. Resources: M.F.-G. and J.G.-M. Writing—Original Draft: F.A.-M.A. Writing—Review & Editing: F.A.-M.A., M.A., B.P.-G., M.-T.M.-M., A.F.-E., J.R.-R., M.F.-G. and J.G.-M. Visualization: F.A.-M.A. Supervision: M.F.-G. and J.G.-M. Project administration: J.G.-M. Funding acquisition: J.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. None of the authors have a financial arrangement or affiliation with any product or services used or discussed in this article.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meschberger-Annweiler, FA., Ascione, M., Porras-Garcia, B. et al. Virtual reality: towards a better prediction of full body illusion — a mediation model for healthy young women. Virtual Reality 28, 157 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-024-01051-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-024-01051-7