Abstract

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors affecting a quarter of the global population, with diet playing a significant role in its progression. The aim of this study is to compare the effectiveness of the Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score (DDRRS) and the Macronutrient Quality Index (MQI) scoring systems in assessing the diet-related risk of metabolic syndrome.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, data from 7431 individuals aged between 30 and 70 years, obtained from the Mashhad Cohort Study, were utilized to evaluate the risk factors of metabolic syndrome. A valid semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to assess participants’ dietary intake. The MQI was calculated based on carbohydrate, fat, and healthy protein components, while the DDRRS was also computed. Anthropometric measurements and blood samples were taken to determine the presence of metabolic syndrome. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the association between MQI and DDRRS with metabolic syndrome and its components.

Results

According to the crude model, we observed lower odds of MetS in the highest quartile of DDRRS and MQI compared to the lowest quartile (P-trend < 0.001). This trend persisted in the fully adjusted models, revealing odds ratios of 0.399 (95% CI: 0.319-0.500) and 0.597 (95% CI: 0.476–0.749) for DDRRS and MQI, respectively. After controlling for all potential confounders, we observed lower odds of central obesity in the highest quartile of MQI (OR: 0.818, 95% CI: 0.676–0.989, P-trend = 0.027). Furthermore, we found that the odds of high triglyceride levels were lower in the highest quartile of DDRRS compared to the lowest quartile (OR: 0.633, 95% CI: 0.521, 0.770, P-trend < 0.001).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study indicates that greater adherence to both DDRRS and MQI is linked to a decreased risk of metabolic syndrome and its components. These findings hold significant implications for public health and the development of personalized nutrition strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is characterized by a cluster of risk factors that significantly increase the likelihood of developing diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, or a combination of these conditions [1, 2]. Globally, it is estimated that one-quarter of the world’s population grapples with MetS [3]. Remarkably, the prevalence of MetS in the United States surged by 35% between the 1980s and 2012, as reported by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [4]. In Iran, a comprehensive meta-analysis of 69 studies placed the prevalence of metabolic syndrome at 30.4% [5]. Metabolic syndrome is typically defined by the presence of at least three of the following five conditions: central obesity, elevated Systolic and Diastolic blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mmHg), High blood glucose level (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or Hemoglobin A1c levels ≥ 5.7%), elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL), and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (< 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women) [6].

While various mechanisms have been proposed for the development of MetS, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and neurohormonal activation appear to be its foremost driving forces [7, 8]. Previous studies have shown that elevated blood pressure [9, 10], liver enzymes [11], fasting blood glucose, and triglycerides, along with low HDL cholesterol levels [12], are common in individuals with metabolic syndrome. These factors contribute to a heightened risk of cardiovascular events and are often linked to insulin resistance and central obesity [13]. Numerous risk factors, including genetic and epigenetic factors, lifestyle choices, and physical inactivity, influence the development of MetS. Diet and lifestyle play pivotal roles in MetS development, with high-calorie intake being linked to visceral adiposity—an entity that significantly influences MetS. In addressing the prevention and treatment of MetS, it is vital to acknowledge that not only the quantity but also the composition of macronutrients in one’s diet can profoundly affect the occurrence of MetS [14]. Furthermore, gaining a precise understanding of the intricate interplay between dietary factors and MetS is indispensable for effective control and prevention of this condition.

Dietary factors, including macronutrients and specific food choices, significantly influence the development of metabolic syndrome [14, 15]. High intake of simple carbohydrates and added sugars from processed foods and sugary beverages can lead to insulin resistance and elevated blood glucose levels, contributing to metabolic syndrome. In contrast, complex carbohydrates rich in dietary fiber, such as whole grains, vegetables, and legumes, are associated with a reduced risk of metabolic syndrome [16,17,18]. Additionally, the quality and source of dietary proteins matter, with lean sources like poultry and fish being preferable [19,20,21]. Unsaturated fats found in nuts, seeds, and fatty fish may have protective effects, while saturated fats, primarily from red meat and processed meat, can promote inflammation and insulin resistance [22]. Also, the impact of dietary choices, such as coffee consumption and cereal selection should be considered. Some studies have suggested a potential protective effect of coffee consumption against metabolic syndrome. Coffee is rich in antioxidants and compounds that may improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation [23, 24]. Whole-grain cereals, especially those high in fiber, can be beneficial for metabolic health. They help stabilize blood glucose levels and provide sustained energy, potentially reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome [25, 26].

Comprehensive understanding and precise assessment of these dietary factors are crucial in formulating effective strategies for preventing and managing metabolic syndrome, emphasizing the importance of tailored and informed dietary recommendations. As for the effect of diet on chronic diseases, there are several ways to assess the relationship between the quality of a diet and chronic disease, one of which was done by Rhee et al. in 2015, which investigated the relationship between diet quality and diabetes by creating a score called the “dietary diabetes risk reduction score (DDRRS)“ [27]. The main concept behind this score was that the amount of food consumed that had a direct or reverse connection with diabetes was scored from 1 to 4 [27]. Another way to assess the relationship between diet quality and chronic diseases is to use a score called the Macronutrient Quality Index [28]. Recent studies have shown that diet quality can be determined by checking the balance between macronutrient and micronutrient intake, specifically the proportionality of the macronutrients that provide energy [28]. For this reason, MQI is based on evaluating the carbohydrate quality index (CQI), fat quality index (FQI), and healthy plate protein source quality index (HPPQI) [28]. While these scores were used to examine the effect of diet quality on chronic diseases to the best of our knowledge, they haven’t been compared with each other concerning a chronic disease, which in this case is metabolic syndrome. Therefore, our aim in the present study is to compare DDRRS and MQI scores with each other in the context of metabolic syndrome.

Materials and methods

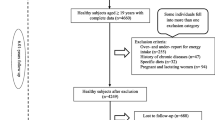

Study design and participants

This study utilized data from the Mashhad PERSIAN Cohort, a prospective study involving individuals of Iranian origin aged 30–70, residing in Mashhad for at least 9 months per year, with no intention of emigrating within the next 2 years. The data specifically used for this cross-sectional analysis were collected between 2021 and 2022. The questionnaire comprised 482 items covering general, medical, and nutrition-related topics. Individuals with physical or intellectual disabilities were excluded from the study. Further information on PERSIAN cohort methods and strategies can be found in a study by Poustchi et al. [29]. Samples with incomplete, underreported, or over reported information were excluded from the study. Ultimately, 7431 eligible individuals were included. This study received approval from the research ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences under code IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1401.277.

Exposure assessment

People’s dietary intake in the past year was evaluated using a valid semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire with 134 items [30]. The questionnaire in the PERSIAN cohort was administered by trained nutritionists. Participants were asked to indicate the frequency of their consumption of each food item over the past year, reporting on a daily, weekly, monthly, or annual basis. Subsequently, the portion sizes of reported foods, quantified in household measures, were converted into grams using the Iranian food composition tables and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) [31, 32].

The macronutrient quality index was calculated from the dietary intake collected in the FFQ. MQI was defined as summing up three sub-indexes: the carbohydrate quality index (CQI), the fat quality index (FQI), and the healthy plate protein source quality index (HPPQI), as follows, MQI = CQI + FQI + HPPQI [33].

The CQI is based on 4 carbohydrate quality domains: glycemic index (GI), total dietary fiber intake (g/d), ratio of carbohydrates from solid/total (solid + liquid) carbohydrates, and ratio of carbohydrates from whole grains/carbohydrates from total grains (whole grains + refined grains or their products). Liquid carbohydrates were calculated by summing carbonated, sugary, soft drinks, juices, milk, dough, and cocoa milk (7 items in the FFQ), while solid carbohydrates corresponded to the carbohydrate content of other foods with any carbohydrate content. On the other hand, 5 items in the FFQ (Barbary bread, Sangak, wheat, barley and corn) were considered as whole grains. Five items included in the FFQ (bread lavash, baguette, cooked rice, pasta and noodles, types of biscuits and crackers) were considered as refined grains. For each of its four components, the participants were grouped into quintiles and received a value (from 1 to 5) according to each quintile (only for GI the values were in reverse). We constructed the CQI summing for each participant the four values. Finally, CQI was obtained from the sum of four components.

To calculate the FQI as a continuous variable, the following ratio was used:

These four components were given the same weighting in the FQI.

The HPPQI has been created based on the nutritional protein quality recommendations found in the last international dietary guidelines [34,35,36]. This new dietary quality index was calculated with the following ratio:

The foods located in the numerator and denominator reflect healthy and unhealthy source of proteins, respectively, according to the Harvard’s Healthy Eating Plate [37].

Finally, to calculate each of the MQI criteria, the weight of each of the criteria, CQI, FQI and HPPQI was equal. Participants were grouped into quintiles for each sub index and assigned values from 1 point (1st quintile) to 5 points (5th quintile). Finally, the MQI score was calculated by adding the values of each sub-index, from 3 (worst quality) to 15 points (best quality) (Table 1).

Dietary diabetes risk reduction score based on Rhee et al.‘s study [27] focusing on 9 components including higher consumption of cereal fiber, nuts (walnuts, peanut, almonds, Hindi, pistachios, hazelnuts, other nuts), coffee, whole fruits (raisins, plums, banana, watermelon, apples, pears, strawberries, apricot, plums, nectarines peaches) and polyunsaturated fatty acids: saturated fatty acids (P: S ratio) and lower consumption of red or processed meat (hamburger, sausages kilbasa salami, red meat any kind), sugar-sweetened beverages (fruit juice fresh, soda drinks, non-alcoholic malt beverage), trans fatty acids and glycemic index (GI) was determined. For each component, subjects were classified into quintiles according to their intake ranking, and component scores were used for cereal fiber, nuts, coffee, whole fruits and P: S ratio to determine the individual’s quintiles rankings. Scores were reversed for red or processed meats, sweetened beverages, trans fat, and GI. Therefore, individuals in the lowest quintile were given a score of 5 points, and those in the highest quintile were scored 1 point. The scores of all nine items were then summed to calculate the DDRRS. The range of total DDRRS was from 9 (minimum adherence) to 45 (maximal adherence).

Assessment other variables

Weight (kg), height (cm), and waist circumference (cm) were measured using US National Institutes of Health protocols [38]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m2). The bioelectrical impedance analysis was also performed using Inbody 770 (Inbody Corporation, Seoul, Korea).

The blood sample was taken after 10–12 h of overnight fasting in a sitting position according to the standard protocol. Biochemistry tests of concentrations of fasting blood glucose, liver function indices (i.e. alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase and alkaline phosphatase), and lipid profile (i.e. total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides) were performed [39].

Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the joint interim statement as the presence of any 3 of 5 following factors [40]: (1) abdominal obesity as WC ≥ 95 cm for both genders, according to the new cutoff points of WC for Iranian Adults [41]; (2) FPG ≥ 100 mg/dl or drug treatment; (3) fasting TGs ≥ 150 mg/dl or drug treatment; (4) fasting HDL-C < 50 mg/dl for women and < 40 mg/dl for men or drug treatment; and (5) high BP was defined as SBP ≥ 130 mmHg, DBP ≥ 85 mmHg, or antihypertensive drug treatment.

The comprehensive survey consisted of nine distinct sections that delved into various aspects of the participants’ lives, including demographics, socioeconomic status, occupation, lifestyle, sleep, circadian rhythm, and physical activity. To determine socioeconomic status, a wealth score index was utilized, which took into account factors such as access to appliances, technology, and transportation. Participants were asked to report their physical activity levels in terms of metabolic equivalent hours per week.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 25.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used to perform all analyzes. The normality of the variables was checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Participants were categorized according to quartiles of MQI and DDRRS cut-points; baseline characteristics of the participants are presented as the mean ± SD for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. One-way Anova and Chi-square were used to test the trends of continuous and categorical variables across quartiles of MQI and DDRRS, respectively. Binary logistic regression analyses were used with MetS (and its components) as the dependent variable and MQI and DDRRS as an independent variable to estimate the odds ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The first quartile of MQI and DDRRS is considered as the reference category. Potential confounders were sex, age, physical activity, smoking, daily energy intake and wealth score index. P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The research population’s fundamental socio-demographic and biological parameters across DDRRS and MQI quartiles are reported in Table 2. Participants in the last quartile of DDRRS were more likely to be older, had higher BMI, body fat mass, and higher HDL compared to first quartile (P < 0.05). However, physical activity, AST, ALT, fat free mass, and triglyceride levels decreased across the quartiles of DDRRS (P < 0.05). Changes in diastolic blood pressure, waist circumference, LDL, total cholesterol, FBG were inconsistent through the quartiles of DDRRS. In addition, changes across the MQI quartiles were different in some biological and socio-demographic parameters. Compared to the lowest quartile, in the last quartile participants were older, had higher body fat mass, and HDL levels (P < 0.05). On the other hand, fat free mass (FFM) levels decreased across the quartiles (P = 0.024). No significant differences between quartiles of MQI and other variables were observed.

Selected dietary intake of participants across DDRRS and MQI quartiles are represented in Table 3. Participants in the top quartile of MQI and DDRRS had significantly different intakes of some food groups and nutrients compared with the first quartile. For example, individuals at the last quartile of DDRRS and MQI had higher dietary intake of cereal fiber, coffee, PUFA/SFA ratio, and nuts, as well as lower intake of red and processed meat, sugar sweetened beverages, and also the glycemic index compared with those in the first quartile. While total energy, protein, and intake were increased across MQI quartiles, they decreased across DDRRS quartiles.

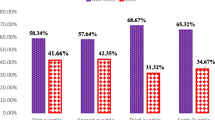

The odds ratio of MetS across quartiles of DDRRS and MQI are shown in Table 4. In the crude model the odds of MetS were lower in the highest quartile of DDRRS and MQI compared to the lowest one (P-trend < 0.001). In the study, participants who followed the DDRRS and MQI diets had a lower risk of developing MetS compared to those who followed the diets less closely. This was true even after adjusting for age, sex, physical activity, and energy. The odds ratios for the highest adherence group were 0.393 (95% CI: 0.315–0.490) for DDRRS and 0.595 (95% CI: 0.475–0.746) for MQI. These trends were also observed in the fully adjusted models, with odds ratios of 0.399 (95% CI: 0.319-0.500) for DDRRS and 0.597 (95% CI: 0.476–0.749) for MQI.

The multivariable-adjusted odds ratio and 95% CI of metabolic syndrome components risk across quartiles of MQI and DDRRS are presented in Table 5. After considering all potential confounders, the odds of central obesity were lower in the highest quartile of MQI (OR: 0.818, 95% CI: 0.676–0.989, P-trend = 0.027). Neither in the crude model nor in fully adjusted models did elevated blood pressure significantly change across the quartiles of DDRRS and MQI. In relation to MQI, the odds of high blood glucose levels were significantly lower in the highest quartile compared to the lowest quartile (P-trend < 0.012). However, although higher MQI was associated with lower odds of elevated TG levels and low HDL cholesterol, these associations were not statistically significant in the fully adjusted model (TG: OR = 0.822, 95% CI: 0.675–1.002, P-trend = 0.005; HDL: OR = 0.835, 95% CI: 0.674–1.034, P-trend = 0.050).

In relation to DDRRS, the chances of having high blood glucose were lower in the highest DDRRS quartile compared to the lowest quartile (P-trend < 0.001). Additionally, the odds of high TG levels were lower in the highest quartile of DDRRS compared to the lowest one (OR: 0.633, 95% CI: 0.521–0.770, P-trend < 0.001), and a significant decreasing trend in the odds ratios of low HDL levels was observed across increasing DDRRS quartiles. However, there was no significant association between DDRRS and central obesity.

Discussion

In this current cross-sectional study, we conducted a comprehensive comparison between the MQI and the DDRRS within the context of metabolic syndrome. The notable findings revealed a direct correlation: as both the MQI and DDRRS increased, a corresponding reduction in the likelihood of metabolic syndrome was observed. Importantly, this relationship persisted even when considering potentially influential factors such as age, gender, physical activity, energy intake, socioeconomic status, and smoking habits. Moreover, a higher MQI score emerged as a potential protective factor, associated with a decreased likelihood of central obesity, elevated blood glucose levels, increased triglycerides, and reduced HDL cholesterol levels. Notably, this effect remained robust and independent of the aforementioned confounding variables. Similarly, an elevated DDRRS score demonstrated a substantial association with a reduced likelihood of elevated blood glucose levels, elevated triglycerides, and reduced HDL cholesterol levels, with its impact transcending the influence of the previously mentioned variables.

To the best of our knowledge, there appears to be a lack of articles investigating the potential relationship between MQI and metabolic syndrome. Nevertheless, there have been various studies that have explored the correlation between this score and other comparable health statuses [42, 43], as well as some research that has delved into the association between the analogous diet quality score and metabolic syndrome [44,45,46]. The findings of our study on the inverse association of MQI with metabolic syndrome are consistent with the studies of Abdul Rahman et al. [44], Kim et al. [45], and Ghalandari et al. [46]. Overall, these studies collectively suggest that diet quality, as measured by the DQI-I, may be associated with MetS and its components in certain populations. However, the associations varied among different studies and were influenced by factors such as gender and food insecurity. These findings underscore the importance of considering individual factors and population characteristics when investigating the relationship between diet quality and metabolic health. Additionally, studies in diverse populations are necessary to generalize the findings and establish more comprehensive dietary guidelines for improving metabolic health.

Due to MQI, two articles explored the association of a multidimensional MQI with different health outcomes in a Mediterranean cohort. In the first study by Santiago et al. [28], the researchers found no significant association between the overall MQI and all-cause mortality risk. However, a higher Carbohydrate Quality Index (CQI), indicative of better carbohydrate quality, was significantly associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality. In the second study, a significant inverse relationship was observed between the Macronutrient Quality Index (MQI) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. This finding suggests that greater adherence to the multidimensional MQI, reflecting high-quality macronutrient intake, was associated with a lower risk of CVD in the Mediterranean cohort [43].

These findings suggest that the quality of macronutrient intake, as assessed by the MQI, may influence health outcomes in this population. Specifically, higher carbohydrate quality, as indicated by the CQI, may be linked to a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, while overall higher macronutrient quality, as captured by the multidimensional MQI, may be associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease. It’s important to note certain limitations in these studies, including potential residual confounding and the likelihood of measurement error in dietary assessments. Additionally, both studies were conducted in a Mediterranean cohort, which could restrict the generalizability of the findings to populations with different dietary patterns and lifestyles.

The findings of our study on the inverse relationship between DDRRS and metabolic syndrome are consistent with Mirmiran et al.‘s study [47]. As far as we know, there are no other articles that explore the connection between DDRRS and metabolic syndrome. However, there are several studies that examine how this score is related to other comparable metabolic irregularities [48, 49]. The three articles investigated the association of DDRRS with different health outcomes, namely cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [49], MetS incidence [47], and body composition parameters [48]. The first study by Asghari et al. [49] found no significant association between DDRRS and CVD risk. In contrast, the second study conducted by Mirmiran et al. [47] found that individuals with higher adherence to the DDRRS had a significantly reduced risk of MetS. This association was observed after adjusting for confounding variables and indicated that a diet in line with the DDRRS may be beneficial in reducing the risk of MetS in Iranian adults. The findings of the third study by Karimi et al. [48] suggested that higher adherence to DDRRS was associated with lower levels of various body fat-related indicators, such as visceral adiposity index, lipid accumulation product, trunk fat percent, body fat mass. Although no significant association was found between DDRRS and skeletal muscle mass (SMM), the results imply that adhering to the DDRRS might lead to improvements in body fat distribution and composition in overweight and obese women.

These three articles contribute valuable insights into the potential health benefits of the Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score. While the first study did not find a significant association between DDRRS and CVD risk, the second study demonstrated a positive link between DDRRS and MetS incidence reduction. Additionally, the third study highlighted the potential for DDRRS adherence to improve body composition in overweight and obese women, particularly in reducing visceral adiposity and body fat-related parameters.

Consuming more dietary fiber and foods with low GI, which are positive components of MQI, causes a lower and slower increase in blood glucose [50]. A diet rich in fiber may prevent metabolic syndrome by reducing insulin and insulin resistance, increasing satiety and blood glucose control, and lowering fasting triglycerides and LDL cholesterol [51]. By consuming more MUFA and PUFA fats, which are positive components of MQI, one can improve insulin sensitivity, lipid profile, blood pressure, and inflammation, as these fats can lower LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, increase HDL cholesterol levels, and modulate inflammatory responses [52,53,54,55].

The beneficial effect of DDRRS in decreasing the risk of MetS could be attributed, in part, to the inclusion of nuts, coffee, unsaturated fatty acids, and cereal fibers as positive components, while red and processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), trans fatty acids, and high glycemic load (GL) are considered negative components [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Consuming more of the positive components of DDRRS plays a crucial role in ameliorating metabolic syndrome. Research indicates that diets rich in fiber with low glycemic index (GI) levels can reduce nutrient absorption, suppress appetite, regulate energy homeostasis, alter intestinal microbiota, modulate inflammatory cytokines and endothelial dysfunction, regulate hormones, and improve blood glucose levels. These mechanisms contribute to the reduction of metabolic syndrome components, including blood glucose control, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, obesity, central obesity, and blood pressure [58, 59, 64, 65]. The antioxidant compounds present in nuts and coffee, such as vitamin E, niacin, potassium, magnesium, fiber, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), polyphenols, phytosterols, and other dietary antioxidants, have been shown to reduce inflammation, improve endothelial function, insulin resistance, and insulin secretion. These effects contribute to lowering the risk of metabolic syndrome [56, 60, 66].

Reducing the consumption of negative components of DDRRS is crucial for preventing metabolic syndrome. Red and processed meats are rich in total fat, saturated fat, and heme-iron, which can contribute to the development of obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglycemia. Moreover, high saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake is associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome. Additionally, frequent consumption of red and processed meats elevates levels of inflammatory mediators, such as C-reactive protein, promotes the production of nitrosamines, and increases oxidative stress, further heightening the risk of metabolic syndrome [62]. Trans fatty acids have adverse effects on circulating fat levels, systemic irritation, disruption of endothelial function, increased visceral fat, body weight, and insulin resistance, which cause metabolic syndrome [63]. Due to their low satiety potential and incomplete compensatory reduction in energy intake, high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) results in a positive energy balance and weight gain. This propensity for weight gain contributes to an elevated risk of metabolic syndrome [61].

The MQI and DDRRS are distinct dietary indices used to evaluate diet quality. Our study’s findings reveal an intriguing contrast in dietary patterns between the MQI and DDRRS. The MQI primarily evaluates macronutrient intake quality, emphasizing protein, fat, and carbohydrate ratios relative to recommended levels. Our results demonstrate that MQI scores increased across quartiles, indicating an overall enhancement in macronutrient quality within these quartiles. This suggests that individuals with higher MQI scores typically adhere to diets with more favorable macronutrient compositions. In contrast, our data illustrates a noticeable decrease in total energy, protein, and intake across DDRRS quartiles. This finding underscores DDRRS’s unique approach, which considers a broader array of dietary components beyond macronutrients. DDRRS incorporates dietary elements such as fiber, whole grains, nuts, fruits, vegetables, sugar-sweetened beverages, coffee, and flavonoids, collectively representing a holistic assessment of dietary quality.

This intriguing discrepancy between the two indices prompts further reflection on the intricate interplay of dietary factors in relation to health outcomes. While MQI has demonstrated its associations with a reduced risk of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, DDRRS, with its focus on diabetes risk reduction, underscores the significance of a broader dietary approach. The fact that higher DDRRS scores coincide with reduced energy intake might indicate a dietary pattern conducive to weight management and glycemic control, which is particularly relevant in the context of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes prevention.

However, it is important to note that while both dietary indices were shown to be effective in reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome, they do not impact all metabolic parameters equally. As seen in Table 2 of our study, individuals in the highest quartile of the DDRRS score exhibited more significant improvements in liver enzymes and fasting blood glucose levels compared to those with high MQI scores. This suggests that the DDRRS may have a stronger effect on these specific metabolic outcomes, possibly due to its focus on components that directly influence glucose metabolism and liver function. On the other hand, the MQI, with its emphasis on overall macronutrient quality, still plays a vital role in improving other aspects of metabolic health, such as lipid profiles and obesity markers. These nuances highlight the complementary nature of the two indices and suggest that a comprehensive dietary approach incorporating the strengths of both could be most beneficial for metabolic syndrome prevention.

Nevertheless, it is essential to address certain adverse findings observed in our study. Specifically, an increase in body fat percentage and a decrease in fat-free mass were noted across the quartiles of both the MQI and DDRRS indices. Additionally, total cholesterol levels were observed to increase in the highest DDRRS quartile. These changes could be perceived as negative outcomes in terms of body composition and lipid profile. However, it is crucial to consider that HDL cholesterol, a positive marker in metabolic health, showed an increase, and triglycerides, a key factor in metabolic syndrome, decreased across the quartiles. Furthermore, as indicated in Table 5, participants in the higher quartiles of both dietary indices had a significantly lower risk of abdominal obesity and elevated triglyceride levels, which are central components of metabolic syndrome. Therefore, while acknowledging the negative aspects of body composition changes, the overall benefits of adherence to these dietary patterns, particularly in reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome, remain evident.

Overall, according to the components of MQI and DDRRS, these dietary scores are rich in antioxidant vitamins and minerals, and phenolic compounds, and have a high unsaturated fatty acid content that mediates theirs effects on metabolic abnormality through possible mechanisms including anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-atherogenic properties, decreasing visceral adiposity and improving hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia.

Strength and limitation

In the present study, we conducted an examination on a substantial sample size obtained from the PERSIAN cohort, aiming to compare two distinct dietary indices and their potential association with metabolic syndrome. However, it is important to acknowledge that our investigation is of cross-sectional nature, thus precluding the assessment of causal relationships; rather, it allows only for the exploration of associations between variables. Moreover, it is imperative to consider the study population’s characteristics, which primarily consisted of employees affiliated with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. While this sample demonstrated an adequate distribution within the city, we recognize it as a notable limitation, as its representativeness for the entire population may be subject to scrutiny.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the potential benefits of higher adherence to both DDRRS and MQI in reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome and its associated components, particularly central obesity, elevated blood glucose, and high triglyceride levels. These insights contribute to the growing body of evidence on the interplay between dietary patterns and metabolic health, providing valuable guidance for public health interventions and personalized nutrition strategies aimed at combating metabolic syndrome. However, it is essential to acknowledge that our study is of cross-sectional design, limiting our ability to establish causality. Therefore, further research, preferably of longitudinal design, involving more diverse and representative cohorts, would be valuable to validate and expand upon these intriguing results.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(14):1113–32.

Lemieux I, Després JP. Metabolic syndrome: past, Present and Future. Nutrients. 2020;12(11).

Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(2):12.

Fahed G, Aoun L, Bou Zerdan M, Allam S, Bou Zerdan M, Bouferraa Y, Assi HI. Metabolic syndrome: updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2).

Kalan Farmanfarma K, Kaykhaei MA, Adineh HA, Mohammadi M, Dabiri S, Ansari-Moghaddam A. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Iran: a meta-analysis of 69 studies. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(1):792–9.

Kassi E, Pervanidou P, Kaltsas G, Chrousos G. Metabolic syndrome: definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 2011;9:48.

Cheng TO. Cardiac syndrome X versus metabolic syndrome X. Int J Cardiol. 2007;119(2):137–8.

Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(5):727–47.

Hermida RC, Chayán L, Ayala DE, Mojón A, Domínguez MJ, Fontao MJ, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome and blood pressure Nondipping Profile in untreated hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(3):307–13.

Zidek W, Naditch-Brûlé L, Perlini S, Farsang C, Kjeldsen SE. Blood pressure control and components of the metabolic syndrome: the GOOD survey. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8(1):51.

Kim HR, Han MA. Association between serum liver enzymes and metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8):1658.

Kawamoto R, Tabara Y, Kohara K, Miki T, Kusunoki T, Takayama S, et al. Relationships between lipid profiles and metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and serum high molecular adiponectin in Japanese community-dwelling adults. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:79.

Samson SL, Garber AJ. Metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43(1):1–23.

Santiago S, Zazpe I, Bes-Rastrollo M, Sánchez-Tainta A, Sayón-Orea C, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, et al. Carbohydrate quality, weight change and incident obesity in a Mediterranean cohort: the SUN Project. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(3):297–302.

Fogelholm M, Anderssen S, Gunnarsdottir I, Lahti-Koski M. Dietary macronutrients and food consumption as determinants of long-term weight change in adult populations: a systematic literature review. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56(1):19103.

Volek JS, Fernandez ML, Feinman RD, Phinney SD. Dietary carbohydrate restriction induces a unique metabolic state positively affecting atherogenic dyslipidemia, fatty acid partitioning, and metabolic syndrome. Prog Lipid Res. 2008;47(5):307–18.

Volek JS, Feinman RD. Carbohydrate restriction improves the features of metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome may be defined by the response to carbohydrate restriction. Nutr Metabolism. 2005;2(1):1–17.

Krauss RM, Blanche PJ, Rawlings RS, Fernstrom HS, Williams PT. Separate effects of reduced carbohydrate intake and weight loss on atherogenic dyslipidemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(5):1025–31.

Shin H, Cho E, Lee H, Fung T, Rimm E, Rosner B, Damsgaard CT, Papadaki A, Jensen SM, Ritz C, Dalskov SM, Hlavaty P, Saris WHM, Martinez JA, Handjieva-Darlenska T, Andersen MR, Stender S, Larsen TM, Astrup A, Mølgaard C et al. and Michaelsen KF on behalf of Diogenes. Higher protein diets consumed ad libitum improve cardiovascular risk markers in children of overweight parents from eight European countries. J Nutr 2013; 143: 810–7. J Nutr. 2013;143:810-7.

Shang X, Scott D, Hodge A, English DR, Giles GG, Ebeling PR, Sanders KM. Dietary protein from different food sources, incident metabolic syndrome and changes in its components: an 11-year longitudinal study in healthy community-dwelling adults. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(6):1540–8.

Saravanan D, Khatoon BS, Sabarathinam S. A narrative review on the impact of processed foods/junk foods/preserved foods: why special attention is required to prevent metabolic syndrome? Obes Med. 2023;42:100507.

Julibert A, del Mar Bibiloni M, Tur JA. Dietary fat intake and metabolic syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Nutr Metabolism Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;29(9):887–905.

Dludla PV, Cirilli I, Marcheggiani F, Silvestri S, Orlando P, Muvhulawa N, et al. Potential benefits of coffee consumption on improving biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in healthy individuals and those at increased risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Molecules. 2023;28(18):6440.

Corbi-Cobo-Losey MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez MÁ, Gribble AK, Fernandez-Montero A, Navarro AM, Domínguez LJ, et al. Coffee Consumption and the Risk of Metabolic Syndrome in the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ Project. Antioxidants. 2023;12(3):686

Clemente-Suárez VJ, Mielgo-Ayuso J, Martín-Rodríguez A, Ramos-Campo DJ, Redondo-Flórez L, Tornero-Aguilera JF. The Burden of Carbohydrates in Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2022;14(18):3809.

Bullón-Vela V, Abete I, Tur JA, Pintó X, Corbella E, Martínez-González MA, et al. Influence of lifestyle factors and staple foods from the Mediterranean diet on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among older individuals with metabolic syndrome features. Nutrition. 2020;71:110620.

Rhee JJ, Mattei J, Hughes MD, Hu FB, Willett WC. Dietary diabetes risk reduction score, race and ethnicity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):596–603.

Santiago S, Zazpe I, Fernandez-Lazaro CI, de la Bes-Rastrollo OV, Martinez-Gonzalez M. MA. Macronutrient Quality and all-cause mortality in the SUN Cohort. Nutrients. 2021;13(3).

Poustchi H, Eghtesad S, Kamangar F, Etemadi A, Keshtkar A-A, Hekmatdoost A, et al. Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in Iran (the PERSIAN Cohort Study): Rationale, objectives, and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;187(4):647–55.

Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(1):51–65.

Laboratory TND. Food Composition Table (FCT), Food and Nutrition Information Center, United State Department of Agriculture (USDA) fdc.nal.usda.gov.2021 [.

Azar M, Sarkisian E. Food composition table of Iran. Tehran: National Nutrition and Food Research Institute, Shaheed Beheshti University. 1980;65.

Santiago S, Zazpe I, Fernandez-Lazaro C. Macronutrient quality and all-cause mortality in the SUN cohort. Nutrients. 2021.

http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/USDoHaHSUSDoADGfAAo

(accessed on 15 December 2020). HTHCSoPTNSWSIEAohwhhenw-s-y-ep.

Otten J, Hellwig J, Meyers L. Institute of medicine dietary reference intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements. Washington, DC: National Academies; 2006.

Plate HE. The nutrition source. Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health https://www.hsphharvardedu/nutritionsource/healthy Accessed. 2021;22.

Control CfD. Prevention. National health and nutrition examination survey (nhanes): Anthropometry procedures manual. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007:15 – 6.

Tohidinezhad F, Khorsand A, Zakavi SR, Rezvani R, Zarei-Ghanavati S, Abrishami M, et al. The burden and predisposing factors of non-communicable diseases in Mashhad University of Medical Sciences personnel: a prospective 15-year organizational cohort study protocol and baseline assessment. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1637.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5.

AZIZI F, Hadaegh F, KHALILI D, Esteghamati A, HOSSEIN PF, Delavari A, et al. Appropriate definition of metabolic syndrome among Iranian adults. report of the Iranian National Committee of Obesity; 2010.

Santiago S, Zazpe I, Fernandez-Lazaro CI, de la Bes-Rastrollo OV, Martínez-González M. M. Macronutrient Quality and all-cause mortality in the SUN Cohort. Nutrients. 2021;13(3).

Vanegas P, Zazpe I, Santiago S, Fernandez-Lazaro CI, de la Martínez-González OV. Macronutrient quality index and cardiovascular disease risk in the Seguimiento Universidad De Navarra (SUN) cohort. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(7):3517–30.

Abdurahman A, Bule M, Fallahyekt M, Abshirini M, Azadbakht L, Qorbani M, Dorosty AR. Association of Diet Quality and Food Insecurity with metabolic syndrome in obese adults. Int J Prev Med. 2021;12:138.

Kim M, Kim J, Bae W, Kim S, Lee Y, Na W, Sohn C. Relationship between nutrients intakes, dietary quality, and serum concentrations of inflammatory markers in metabolic syndrome patients. Korean J Community Nutr. 2011;16(1):51–61.

Ghalandari H, Askarpour M, Nouri M, Safarpour AR, Fattahi MR, Akbarzadeh M. Quality of Diet and Odds of Metabolic Syndrome in Iranian Adults: Baseline Results from the PERSIAN Kavar Cohort Study (PKCS). Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2023.

Mirmiran P, Farhadnejad H, Teymoori F, Asghari G, Parastouei K, Azizi F. The association of dietary diabetes risk reduction score and its components with risk of metabolic syndrome incident in tehranian adults. BMC Endocr Disorders. 2021;21(1):206.

Karimi M, Shiraseb F, Mofidi M, Khadem A, Ebrahimi S, Mirzaei K. The association between dietary diabetic risk reduction score with anthropometric and body composition variables in overweight and obese women: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):8130.

Asghari G, Farhadnejad H, Teymoori F, Emamat H, Shahrzad MK, Habibi-Moeini AS, et al. Association of Dietary Diabetes Risk reduction score with risk of Cardiovascular diseases in the Iranian Population: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Heart Lung Circ. 2022;31(1):101–9.

Schulze MB, Liu S, Rimm EB, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and dietary fiber intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in younger and middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(2):348–56.

Jovanovski E, Khayyat R, Zurbau A, Komishon A, Mazhar N, Sievenpiper JL, et al. Should viscous fiber supplements be considered in diabetes control? Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):755–66.

Summers L, Fielding B, Bradshaw H, Ilic V, Beysen C, Clark M, et al. Substituting dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat changes abdominal fat distribution and improves insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia. 2002;45:369–77.

McEwen B, Morel-Kopp M-C, Tofler G, Ward C. Effect of omega-3 fish oil on cardiovascular risk in diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(4):565–84.

Dangardt F, Osika W, Chen Y, Nilsson U, Gan L-M, Gronowitz E, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation improves vascular function and reduces inflammation in obese adolescents. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(2):580–5.

Meyer BJ, Lane A, Mann N. Comparison of seal oil to tuna oil on plasma lipid levels and blood pressure in hypertriglyceridaemic subjects. Lipids. 2009;44:827–35.

Guo X-f, Li X, Shi M, Li D. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and metabolic syndrome risk: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):703.

Zhang Y, Zhang D-Z. Relationship between nut consumption and metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019;38(6):499–505.

Juanola-Falgarona M, Salas‐Salvadó J, Buil‐Cosiales P, Corella D, Estruch R, Ros E, et al. Dietary glycemic index and glycemic load are positively associated with risk of developing metabolic syndrome in middle‐aged and elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):1991–2000.

Chen J-P, Chen G-C, Wang X-P, Qin L, Bai Y. Dietary fiber and metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis and review of related mechanisms. Nutrients. 2017;10(1):24.

Shang F, Li X, Jiang X. Coffee consumption and risk of the metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2016;42(2):80–7.

Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2477–83.

Kim Y, Je Y. Meat consumption and risk of metabolic syndrome: results from the Korean population and a meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):390.

Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Trans fatty acids: effects on metabolic syndrome, heart disease and diabetes. Nat Reviews Endocrinol. 2009;5(6):335–44.

Chandalia M, Garg A, Lutjohann D, Von Bergmann K, Grundy SM, Brinkley LJ. Beneficial effects of high dietary fiber intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1392–8.

He M, van Dam RM, Rimm E, Hu FB, Qi L. Whole-grain, cereal fiber, bran, and germ intake and the risks of all-cause and cardiovascular disease–specific mortality among women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2010;121(20):2162–8.

Salas-Salvado J, Guasch-Ferre M, Bullo M, Sabate J. Nuts in the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(suppl1):S399–407.

Acknowledgements

This study was extracted from a research project, approved on 17/08/2022 by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (code: 4001926), and sponsored by the University Research Council. The authors appreciate the cooperation and assistance of the University Vice Chancellor for Research.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SRS and ZN contributed to design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data. ZN, KI, and SS contributed to writing the first draft of the manuscript. SRS, ZN, and KI contributed to editing the first draft of the manuscript. SRS supervised the study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study received approval from the research ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences under code IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1401.277.

Consent to participate

Upon arrival at the center, each individual provides written informed consent and credible personal identification documents to complete registration.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Namkhah, Z., Irankhah, K., Sarviha, S. et al. Exploring metabolic syndrome and dietary quality in Iranian adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr 10, 143 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-024-00948-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-024-00948-5