Abstract

Background

Somatization has gained recognition for its potential impact on medical students’ quality of life and career longevity, who function in a high-stress environment and frequently have poor mental health, but somatization is much less researched among other health profession students who strive to excel in the same environments. Both mental and physical health issues predict leaving a career in healthcare. The aims of this scoping review were to describe and characterize somatic symptoms related to mental health in medical, dental, veterinary, nursing, and physical therapy students; define the outcome measures of somatization which were used; and document the existing evidence for interventions to prevent or treat somatization in these populations.

Methods

Developed in alignment with PRISMA-ScR guidelines, a comprehensive search was performed with 17 databases, bibliographic searching, and hand- searching, with eligible primary studies having medical, dental, veterinary, nursing, or physical therapy students, at least one measure of somatization or a statistical analysis of separate mental and physical health measures, written in or translated into English. Data charting was performed by a trained researcher and two authors reviewed each article.

Results

Seventy-three articles met inclusion criteria, inclusive of 51 medical, 14 nursing, seven dental, three veterinary, and zero physical therapy students; and two studies had heterogeneous populations. Studies represented data from 26,200 students from 29 countries. The prevalence of somatization ranged from 5.7% to 85.2% with a weighted average of 34.4%. Commonly reported somatic symptoms were insomnia, temporomandibular disorder, and musculoskeletal pain. Seventeen studies included an intervention aimed at improving somatization or associated mental and physical health outcomes. Twenty different direct somatization outcome measures were used, and we review them based on validity and reliability.

Conclusions

Somatic symptoms were highly prevalent in all assessed health professions and primary articles reported them to be strongly correlated with mental distress. Further research is necessary, particularly in the U.S., which now claims just five primary articles in the past three decades. Research on non- medical health profession students is particularly lacking, as are controlled trials and research examining the effects of somatic symptoms of stress on long-term quality of life and career attrition from the healthcare field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is a wide body of research on the high levels of stress and poor mental health among medical students, but research on physical symptoms which begin or worsen due to stress or poor mental health (i.e. somatization or psychosomatic symptoms), remains relatively scant, particularly among students in other healthcare disciplines [1]. Assessing the prevalence and severity of mental health-related physical symptoms among health profession students is important as it has been hypothesized that burnout and mental ill-health, which is high among healthcare professionals, begins during healthcare schooling [2].

Both mental and physical health symptoms independently predict leaving a career in healthcare, but the relationship or combined effect of mental and physical symptoms has not been well investigated in career attrition [3,4,5,6]. With a global healthcare staffing crisis underway and projected to worsen [7], determining factors which might predict or hasten leaving a career in healthcare, and targeting interventions to those these factors, is essential. Interventions which have shown promise among one group of healthcare students may be easily adapted to another group, and cross-disciplinary sharing can foster innovation and accelerate the state of the science to the benefit of all. To our knowledge and after conducting a comprehensive search, this is the first review to compile and compare interventions for somatization and related mental and physical health markers across multiple healthcare disciplines. The initial disciplines were chosen to align with the expertise of the authors, but further disciplines can and should be targeted.

This study was guided by the psychoneuroimmunological model [8]. Psychoneuroimmunology describes how chronic psychological stress contributes to physiological changes which can lead to physical diseases (i.e., somatization or psychosomatic symptomatology) [8, 9]. Stress-induced symptoms and conditions have been shown to contribute to reduced quality of life, high symptom burden, and high healthcare utilization costs in the U.S [10, 11]. Among healthcare professionals, understanding if and how chronic stress progresses to mental ill-health and/or physical ill-health could lead to both individual and systemic interventions to alleviate symptoms, improve quality of life, and reduce or prevent burnout and career attrition among healthcare professionals.

The research questions for this scoping review were (1) what is the prevalence of somatization reported in the literature for medical, dental, veterinary, nursing, and physical therapy students? (2) What are the types, characteristics and frequencies of the different mental health-related somatic symptoms or disorders reported in medical, dental, veterinary, nursing, and physical therapy students? (3) What are the different outcome measures of mental health-related somatic symptomatology that have been used with medical, dental, veterinary, nursing, and physical therapy students and which are most valid and reliable in this population? (4) Is there support for any approaches to predict, prevent or treat somatic symptoms in medical, dental, veterinary, nursing, and physical therapy students?

Methods

This review was developed in alignment with PRISMA-ScR guidelines [12]. The Arksey and O’Malley framework was used in developing research questions [13].

Eligibility

Eligible articles must have been published, peer-reviewed, and written in or translated to.

English, with any date of publication and any location. The population included medical, dental, nursing, veterinarian, or physical therapy students in any year of school but excluding post-graduate training (e.g., residency). Articles with combined sample data were acceptable unless data were combined with an ineligible population, e.g., nursing students and nurses, without separate outcomes reported. Articles must have included at least one direct measure of somatization, e.g., the Patient Health Questionnaire-15, or at least one psychological measure of stress, anxiety, depression, or burnout statistically associated with at least one physical measure of any kind; e.g., if depression and insomnia were measured and then correlated, the article was eligible. Studies could assess stress, anxiety, depression, and/or burnout, or variations including test anxiety, academic stress, or work stress.

Physical measures could be objective or self-reported. Articles which only had non-specific measures not explicitly measuring a mental or physical health construct were excluded, e.g., smartphone addiction, self-confidence. Reviews, editorials, companion articles, and other non-primary research were excluded.

Search strategies

A comprehensive search was conducted in January 2025 with English language, peer-reviewed, and abstract (AB) filters, of the MEDLINE, PubMed, APA PsycInfo, and CINAHL databases. Additional databases searched were Academic Search Elite, Alt Healthwatch, ERIC, Health Source including the Consumer Edition and the Nursing/Academic Edition, the school edition of MAS Ultra, Web of Science, and Education Full Text. EBSCO Discovery was searched in the categories of complementary & alternative medicine, education, health & medicine, nursing & allied health, nutrition & dietetics, pharmacy & pharmacology, physical therapy & occupational therapy, psychology, public health, science, and veterinary medicine.

We used a structured search strategy which began with Boolean terms and transitioned to MeSH terms to refine results. The MeSH search term was: “‘mental health-related somatic symptoms’ OR ‘unexplained medical symptoms’ OR ‘psychophysiological disorders’ OR ‘psychobiological disorders’ OR ‘somatization’ OR ‘somatisation’ OR ‘somatic distress’ OR ‘somatoform disorder’ OR ‘blood pressure’ OR ‘vital signs’ OR ‘cortisol’ OR ‘biomarker’ OR ‘physiologic’ OR ‘blood’ AND ‘medical students’ OR ‘dental students’ OR ‘veterinary students’ OR ‘physical therapy students’ OR ‘physiotherapy students’ OR ‘allied health students’ OR ‘nursing students.’” A research librarian assisted in ensuring all potential search terms were included.

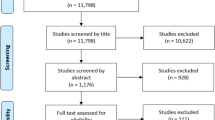

A bibliographic search was done on four relevant articles [14,15,16,17]. The articles from the databases were compared to see if there were frequently occurring journal names and as a result, the Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, and the Journal of Psychosomatic Research were hand-searched online. Two-hundred-and-ten articles were requested after title screening results from the above search strategies. Upon full-text screening, 137 articles were excluded, leaving 73 articles for inclusion in the review; see Fig. 1, PRISMA-ScR flowchart [12].

Updated PRISMA-ScR flowchart [12]

Data charting process

Zotero and Excel were used to collect and manage data. Data charting guidelines were developed based on Sperling et al., [1]. The first author, who is experienced in systematic reviews, extracted data from eligible studies. Data included author and title, study design, program discipline, location, mean age or age range, n, sex, race, ethnicity, outcome name and if it was self-reported or objective, and results including statistics.

Results

Seventy-three articles met inclusion criteria and are included here. Fifty-one included medical students, fourteen included nursing, seven included dental, three included veterinary, and none were found among physical therapy students. Two studies had heterogenous student groups [18, 19]. Study results are stratified and presented by design: observational and correlational studies are detailed in Table 1 and intervention studies are detailed in Table 2.

Study characteristics

Studies were conducted in 29 countries, and two studies sampled from multiple European countries (see Tables 1 and 2). The total sample size of the combined studies was 26,200, with sample sizes ranging from 10 to 4,374. The mean age ranged from 18.0 to 30.2 among studies whose authors reported a mean age. Studies typically had a higher percentage of females; female-identifying participants ranged from 3% to 100%. The majority of the study designs were cross-sectional observational studies (k = 47). Studies were published between 1980 and 2024, with 50 published since 2015.

(Question 1) What is the prevalence of somatization reported in the literature for medical, dental, veterinary, and nursing students worldwide?

Twenty-three studies directly reported the prevalence of somatization in their sample, which ranged from 5.7% to 85.2% (see Tables 1 and 2). See Table 3 for the ranges by discipline among studies that reported prevalence.

(Question 2) What are the types and characteristics of mental health-related somatic symptoms/disorders reported in medical, dental, veterinary, and nursing students?

Twenty-eight studies had a direct measure of somatization or psychosomatic symptoms, though not all reported prevalence (see Tables 1 and 2). Studies that didn’t measure prevalence instead assessed odds ratios, including a study which assessed the odds of females vs. males having somatization (females had significantly higher odds) [34, 59], odds of somatization symptoms in those with different levels of stress (those with moderate to high stress were 2.44–3.17 times more likely have greater somatization) [34], those with insomnia (OR = 1.31 times higher odds of somatization with insomnia than without) [34], an eating disorder diagnosis (OR = 1.55) [34], or smoking cigarettes (OR = 2.78) [34]. Another study found higher odds of somatization among males younger than twenty in rural locales and with low economic class in Egypt (AOR 1.6–8.3) [35].

Two studies reported mean somatization scores on their outcome measures [36, 88]. Another study reported that dental students had significantly higher somatization scores than medical students but did not report the scores [52]. The remaining studies did not report a direct measure of somatization/psychosomatic symptomatology, but rather measured one or more physical factor(s), e.g. insomnia, and then correlated them with one or more psychological factors, e.g. anxiety (Tables 1 and 2 provide the pertinent physical and psychological variable(s) used in each study).

Mental and physical health correlational studies

Along with assessing stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, test anxiety, academic stress, and work stress, studies also measured suicidal ideation [20, 27, 69], emotional exhaustion as a component of burnout [76], quality-of-life (QOL) [60], well-being [86], psychiatric illness [19], psychoticism [66], hostility [88], obsessive-compulsive traits [35, 51, 55, 66], familial conflict [32], interpersonal sensitivity [35, 66], hostility [66, 88], paranoia [66], anger [75], panic disorders [75], resilience [19], mindfulness [39, 87], and coping [56].

There were several physical measures of health utilized. Seventeen articles assessed insomnia/sleep as it related to mental health [24, 25, 27, 28, 34, 39, 43, 47, 50, 55, 57, 59, 61, 64, 68, 76, 82]. Insomnia was found to be significantly associated with somatization [34, 47, 61], stress [43, 57, 59, 64], depression [24, 28], anxiety [39, 50], lower quality of life [24], and burnout [27]. Emotional exhaustion and sleep-related worry were both found to be mediators of the relationship between sleep disturbances and depression [76].

Six studies measured musculoskeletal pain as it related to mental health including depression, with which it was significantly associated [21, 33, 62]; in clinical vs. preclinical students, which found higher musculoskeletal pain in clinical students [23]; and stress, which showed higher musculoskeletal pain in those with stress or academic stress [26, 65]. Further studies found general pain and fatigue associated with suicidal ideation [69], and headache significantly correlated with academic burnout [59].

Three studies assessed temporomandibular disorder (TMD) as it related to anxiety or stress, all among dentistry students [38, 60, 67]. One study did not find significant correlation between TMD and anxiety [38], while the other two studies discovered significant associations with psychological stress (t = 2.65, p = 0.01) and performance anxiety (t = 2.56, p = 0.01) [60] or anxiety in general (OR = 1.55, p = 0.04) [67]. In the one study which compared TMD among preclinical vs. clinical students, clinical students had a significantly higher risk of TMD (OR = 1.65, p = 0.03) [67].

Two studies assessed the relationship of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) with mental health, finding that anxiety increased the risk of FGIDs [40, 68]; another study found stomach and bowel issues were common in those with somatic symptom disorder [43]. Further studies assessed variables including skin-picking in relation to stress, finding significant correlations between skin-picking and perceived stress [49]; ocular disease’s correlation with anxiety and depression (both significant) [22]; and higher stress correlated with larger waist circumference [25]. Three studies evaluated exercise or physical activity, two finding a lack of exercise to be significantly associated with depression [28, 76], and one finding no association with stress [74]. One study on menstrual disorders found no association with stress [30].

Seventeen studies compared somatization prevalence and/or symptoms between genders, most finding female-identifying students reported higher levels and/or severity of somatization [18,19,20, 34, 36, 43, 46, 47, 52, 71, 75]. Four studies found no differences in somatic symptoms between genders [21, 23, 26, 29], and one study found that males had more physical symptoms of stress [35]. Several studies, while technically interventional, did not test interventions designed to assist with stress but rather to test the stress response in various situations (included in Table 1). One study compared history-taking vs. delivering bad news to simulated patients, and all participants had significantly increased heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and cardiac output, with delivering bad news inducing a more intense cardiovascular response [44]. A similar study on low-complexity vs. high- complexity medical simulation showed a trend with serum cortisol levels generally matching anxiety scores, though not at statistically significant levels [72]. A study on the effect of an oral presentation on stress, salivary cortisol, and testosterone found that self-reported stress peaked at different times than cortisol, with cortisol peaking 20 min after the start of the five-minute presentation; no changes were detected in testosterone levels [70]. A further study found that the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), which is comprised of an oral presentation and surprise mental math test in front of a stoic panel, followed by three days of electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring showed self- reported stress was not significantly associated with physical activity, blood pressure, heart rate variability, or hemoglobin A1c [74].

(Question 3) What are the different instruments used to measure mental health-related somatic symptomatology among medical, dental, veterinary, and nursing students?

Twenty outcome measures specifically measured somatization/psychosomatic symptoms (see Table 4). Seven studies used the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15), three studies used the Global Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), two studies used the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), two studies used the Somatic Symptom Scale (SSS-8) and all other studies had a separate measure (see Table 4).

Mental health outcome measures

For studies which had separate measures of mental and physical variables which were then correlated, over 100 different mental and physical health outcome measures were represented; see Tables 1 and 2 for details. For mental health specifically, studies measured anxiety, depression, stress, and burnout as was included in our review’s eligibility criteria, but also reported on stressful life events, coping, help-seeking, personality, obsessive-compulsive traits or disorder, stigma, well-being, self-.

esteem, suicidality, resilience, familial conflict, mindfulness, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, panic disorders, anger, paranoia, psychoticism, and quality of life.

Physical health outcome measures

A variety of different self-reported and objective physical health measures were used in the 73 studies (Tables 1 and 2). The self-reported measures were for eye disease, skin picking, alcohol use disorder, eating disorders, musculoskeletal pain, sleep/insomnia, TMD, and general health or physical symptoms. Twenty-four objective measures were used, including for cortisol (serum and salivary), cardiovascular markers (blood pressure, retinal blood pressure, heart rate, heart rate variability, mean arterial pressure, cardiac output, cholesterol, triglycerides, carotid wall thickness, Fetuin A, Amyloid P), respiratory markers (vital capacity, forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume), metabolic markers (glucose, A1c) immune biomarkers (C-reactive protein, metanephrine, IgA, glucocorticoid receptor expression,

seroconversion speed, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α), cellular markers (red blood cells, leukocytes, lymphocytes), endocrine markers/hormones (testosterone), body morphology (BMI, waist circumference), and body function (reaction time, muscle ergometry).

(Question 4) Is there support for any approaches to predict, prevent, or treat mental health-related somatic symptoms in health profession students?

Out of the 73 studies, 17 contained an intervention and 13 of those were aimed at improving mental and/or physical health in health profession students (Table 2). Yoga interventions were tested in four studies (79,81,86,88]. The results of an RCT on laughter yoga, a practice that incorporates breathing techniques and laughter, were that laughter yoga improved anxiety, depression, negative view of self, somatization, and hostility among n = 38 nursing students; salivary cortisol levels also significantly improved after sessions five, seven, and eight, out of eight total sessions [88]. A second study incorporated 50 min of “traditional” yoga once per week for eight weeks for n = 19 nursing students [79]. Stress and anxiety were both reported to be reduced though significance was not assessed [79]. A separate study assessed Raj Yoga meditation one hour per day for seven days among n = 80 medical students, finding significant reductions in stress and diastolic blood pressure [81]. Lastly, an RCT assessed Pranayam breathing (alternate nostril breathing) vs. Surayanamaskar yoga (specific asanas, or movements) for 40 min per day for six weeks among n = 96 medical students, with results showing the group engaged in Pranayam breathing had decreased anxiety and the group engaged in yoga had increased well-being [86].

Two studies were done using mindfulness meditation, both reporting significantly reduced stress in the intervention groups [78.87]. Alhawatmeh et al. had n = 54 nursing students complete mindfulness mediation for 30 min five days in a row in small groups; along with improved stress, cortisol was also reported to improve significantly in the intervention group [78]. Oró et al. assessed a program based on Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction protocol [105] which met every other week for two hours each, for a total of eight sessions [87]. Along with stress improvements, somatization also significantly decreased in the intervention group of n = 143 medical students, though burnout did not significantly change [87].

Four studies assessed the effect of music [77, 80, 84, 85]. The authors reported that music reduced anxiety during a skills test in one study [77] though not in another [80], reduce BP during structured clinical exams with no effect on anxiety [84], and had little effect on stress compared to a dog therapy group [85]. The only study on bodywork evaluated the effect of weekly sessions of osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) for n = 5 medical students, 15 min per session for six weeks vs. no treatment, showing no significant correlation between stress and salivary cortisol and no significant benefit to the treatment group [89].

Further studies found that a sunrise alarm for two weeks combined with no screen time in bed significantly reduced stress, burnout, and insomnia [82]. A study with a wide mix of psychological interventions including individual, group, educational, relaxation training, and more, significantly reduced somatization, anxiety, and depression [83]. These interventions were assessed in aggregate so determining what may have been beneficial vs. incidental is difficult.

Although not interventions, several other studies assessed characteristics or behaviors which may have the potential to prevent or treat physical symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout [19, 28, 39, 41, 56]. These included health behaviors such as healthy diet, exercise, and sleep [28], resilience [19], trait mindfulness [39], social support [41], and coping strategies [56]. Findings included that higher resilience was significantly correlated with lower somatization (rs = −0.21, p < 0.001) [19]; higher social support was significantly associated with better immune function after a Hepatitis B vaccination (t(34) = 2.21, p < 0.05) [41]; high levels of disengagement coping strategies, such as withdrawal, problem- avoidance, self-criticism, and wishful thinking, were correlated with higher depression scores, and wishful thinking correlated with more physical symptoms (partial corr. 0.34, p < 0.01) [56]; and finally, higher trait mindfulness, specifically ‘nonjudgement of inner experiences’ and ‘acting with awareness,’ were positively correlated with less psychosomatic symptoms, though not at statistically significant levels [39].

Bias

Many of the studies in this review used a single-group cross-sectional design and results may be biased due to lack of randomization or comparison groups. The longitudinal studies had high drop-out rates, as are frequently seen among student populations [32, 39, 41, 42, 55, 76]. Risk of bias is also present among studies with incomplete representation of the population of interest, i.e., the study aim was to assess the student body but not every year was sampled from [24, 42, 45, 47]. Selection bias is very likely with studies being voluntary, as is response bias with the use of self-reported outcome measures.

Discussion

In our review, the prevalence of somatization was 34.4% (ranging from 5.7% to 85.2%) based on a weighted average from 23 studies that reported prevalence. This finding is compelling as it suggests that for 1/3 of the healthcare professional workforce, somatization may begin during the professional training program. This is particularly concerning given the high rates of burnout and turnover (i.e., leaving one’s job and/or profession) observed in healthcare professionals that has only worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic. There is evidence of worse somatic symptoms in young adult students compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic [106].

Medical, dental, veterinary, and nursing students exhibit high levels of stress-related mental and physical health issues. Our findings suggest that delivering interventions to reduce stress and somatization in healthcare professionals may be optimally delivered during the professional training programs. Our review located a number of intervention studies using complementary and alternative approaches (e.g., mindfulness, music, yoga, and deep breathing) with promising yet mixed results, in part, due to pilot designs that were not fully powered. Importantly, our results suggest a connection between the stress that healthcare professionals experience during their training years that may become cumulative and without intervention, may be a factor in the burnout and attrition rates that we now see in our practicing clinical workforce. Thus, offering stress-reduction interventions during the professional training program may offer downstream benefits of a healthier clinical workforce that is less prone to burnout and attrition.

Another key finding was the lack of somatization research among veterinary and physical therapy students and small sample sizes among dental, veterinary, and nursing students compared to the number of medical students. While we calculated a weighted prevalence, there were only two studies each for dental and nursing students which reported prevalence of somatization. We were unable to locate reports of the prevalence of somatization among veterinary students, or any literature whatsoever on physical therapy students and somatization, which limits comparisons and indicates this area is ripe for further research. There are studies suggesting that practicing physical therapists [107] and veterinarians [108] suffer from somatization.

The reported prevalence of somatization had a large range (5.7 to 85.2%). This was expected due to the wide variety of outcome measures and differences in type of symptoms investigated by individual articles, e.g., we wouldn’t necessarily expect insomnia to have the same prevalence as temporomandibular disorder. Besides differences in research aims, the psychoneuroimmunological model informs us that individuals may manifest physical symptoms of stress in different ways and at different time points, or not at all [8]. Different genders may experience or express somatization differently [109], and with a wide variety of countries and cultures included in the articles, differences also likely exist in the expression and reporting of physical and mental health concerns.

Twenty separate somatization/psychosomatic outcome measures were used, as well as many mental and physical health measures which were correlated, suggesting further investigation into a “gold standard” for measuring stress-related somatic symptoms among health profession students may be useful. Psychometric data was not always available among a health profession student population. Of the somatization outcome measures used, the PHQ-15 was the most common (used by seven studies), but did not have the highest validity or reliability as a measure of somatization (Table 4). The Psychosomatic Complaints Questionnaire had the highest reported reliability in the literature (Cronbach α = 0.957) [97], but not all psychometric analyses reported Cronbach’s alpha as a reliability measure. Validity measures were even more diverse and difficult to compare, with measures including sensitivity and specificity, correlation with internal outcome measures, correlation with external “gold standard” outcome measures, and responsiveness; not all reported validity data was supported by statistics.

Limitations of primary articles included that many findings were based on cross-sectional designs and lacked comparison groups, which points to a need for stronger levels of evidence. Findings were also primarily drawn from self-reported outcome measures which pose a risk of response bias. As noted, outcome measures did not consistently have high reliability or validity in measuring somatization.

Limitations

There are several limitations within this scoping review. We excluded gray literature, therefore likely introducing publication bias and possibly missing relevant articles. Many other healthcare disciplines could have been targeted, e.g. optometry students or physician assistant students, who should be included in future reviews. As this is a scoping review, calculations for summary mean prevalence or summary mean age, etc., are not recommended [12]; therefore, summary statistics for different disciplines cannot be compared.

Implications and recommendations

Our findings suggest that further research is needed, including replication of existing interventional studies and inclusion of more healthcare student populations such as dental, veterinary, and physical therapy. Interventions that address both body and mind, such as the yoga and mindfulness studies reviewed here, have more theoretical support and show promise thus far [78, 79, 81, 86,87,88].

Interventions inclusive of healthy diet, exercise, sleep, resilience, social support, and coping strategies may also be beneficial, as several correlational studies show positive results [19, 28, 39, 41, 56]. Further studies using and comparing objective measures would also be beneficial to increase precision and reduce response bias [see 110].

Additionally, novel interventions which address not just individuals, but systemic causes of ill- health, are needed. Stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout among health profession students is not separate from the environment and culture in which healthcare exists. Finding ways to reduce stress by changing how healthcare is delivered, documented, and billed addresses the root causes of stress and poor mental health in healthcare students and professionals, and may be key in preventing physical symptoms and diseases from manifesting. Further research on how and when mental ill-health affects physical health in health profession students may provide insight on ideal intervention time points.

Conclusion

In this scoping review we found that many healthcare profession students (medical, dental, veterinary, and nursing) may be experiencing somatization symptoms linked to stress, anxiety, depression. Gaps in the research examining prevalence of somatization or interventions for somatization were notable among dental and veterinary students, but particularly physical therapy students, where no research was found. Several studies report on interventions which have improved somatization among health profession students, including yoga and mindfulness, but more research is needed. Offering stress- reduction interventions during the professional training program may offer downstream benefits of a healthier clinical workforce that is less prone to burnout and attrition.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Sperling EL, Hulett JM, Sherwin LB, Thompson S, Bettencourt BA. Prevalence, characteristics and measurement of somatic symptoms related to mental health in medical students: a scoping review. Ann Med. 2023;55(2):2242781. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2242781.

Abid R, Salzman G. Evaluating physician burnout and the need for organizational support. Mo Med. 2021;118(3):185.

Bryant-Genevier J, Rao CY, Lopes-Cardozo B, Kone A, Rose C, Thomas I, et al. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, Post-Traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, March–April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(26):947–52. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7026e1.

Fochsen G. Predictors of leaving nursing care: a longitudinal study among Swedish nursing personnel. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(3):198–201. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2005.021956.

Nixon AE, Mazzola JJ, Bauer J, Krueger JR, Spector PE. Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. Work Stress. 2011;25(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.569175.

Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer MB, Neuendorf K, Boissy A, Rothberg MB. Correlates and outcomes of physician burnout within a large academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):856. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0019.

Almutairi SF. Burnout among healthcare professionals: a review of causes, impacts, and alleviation strategies. Rev Contemp Philos. 2023;22:43–52.

Ader R, Cohen N. Behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression. Psychosom Med. 1975;37(4):333–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197507000-00007.

Ader R. Psychoneuroimmunology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001;10(3):94–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00124.

Barsky AJ, Borus J. Somatization and medicalization. JAMA. 1996;275(18):c1398–11398. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.275.18.1398c.

Konnopka A, Kaufmann C, König HH, Heider D, Wild B, Szecsenyi J, et al. Association of costs with somatic symptom severity in patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(4):370–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.08.011.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Straus SE. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Ji X, Guo X, Soh KL, Japar S, He L. Effectiveness of stress management interventions for nursing students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Health Sci. 2024;26(2):e13113. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.13113.

Li H, Upreti T, Do V, Dance E, Lewis M, Jacobson R, et al. Measuring wellbeing: a scoping review of metrics and studies measuring medical student wellbeing across multiple timepoints. Med Teach. 2024;46(1):82–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2231625.

Maity S, Abbaspour R, Bandelow S, Pahwa S, Alahdadi T, Shah S, et al. The psychosomatic impact of yoga in medical education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online. 2024;29(1):2364486. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2024.2364486.

Strehli I, Burns RD, Bai Y, Ziegenfuss DH, Block ME, Brusseau TA. Mind–body physical activity interventions and stress-related physiological markers in educational settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010224.

Antoniadou M, Manta G, Kanellopoulou A, Kalogerakou T, Satta A, Mangoulia P. Managing stress and somatization symptoms among students in demanding academic healthcare environments. Healthcare. 2024;12(24):2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12242522.

Feussner O, Rehnisch C, Rabkow N, Watzke S. Somatization symptoms—prevalence and risk, stress and resilience factors among medical and dental students at a mid-sized German university. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13803. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13803.

Adhikari A, Dutta A, Sapkota S, Chapagain A, Aryal A, Pradhan A. Prevalence of poor mental health among medical students in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1083-0.

Algarni AD, Al-Saran Y, Al-Moawi A, Bin Dous A, Al-Ahaideb A, Kachanathu SJ. The prevalence of and factors associated with neck, shoulder, and low-back pains among medical students at university hospitals in central Saudi Arabia. Pain Res Treat. 2017;2017:1235706. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1235706.

Alkozi H, Alhudhayf H, Alawad N. Association between dry eye disease with anxiety and depression among medical sciences students in Qassim region: cortisol levels in tears as a stress biomarker. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024;17:4549–57. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S488956.

Alshagga MA, Nimer AR, Yan LP, Ibrahim IAA, Al-Ghamdi SS, Radman Al-Dubai SA. Prevalence and factors associated with neck, shoulder and low back pains among medical students in a Malaysian medical college. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):244. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-244.

Angelone AM, Mattei A, Sbarbati M, Orio FD. Prevalence and correlates for self-reported sleep problems among nursing students. J Prev Med Hyg. 2011;52(4):201–8.

Badawy Y, Aljohani NH, Salem GA, Ashour FM, Own SA, Alajrafi NF. Predictability of the development of insulin resistance based on the risk factors among female medical students at a private college in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39112. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39112.

Behera P, Majumdar A, Revadi G, Santoshi J, Nagar V, Mishra N. Neck pain among undergraduate medical students in a premier Institute of central India: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and associated factors. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(7):3574. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_206_20.

Bolatov AK, Seisembekov TZ, Smailova DS, Hosseini H. Burnout syndrome among medical students in Kazakhstan. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00901-w.

Cheung T, Wong S, Wong K, Law L, Ng K, Tong M, et al. Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among baccalaureate nursing students in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(8):779. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13080779.

Chinawa JM, Nwokocha ARC, Manyike PC, Chinawa AT, Aniwada EC, Ndukuba AC. Psychosomatic problems among medical students: a myth or reality? Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10(1):72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0105-3.

Clarvit SR. Stress and menstrual dysfunction in medical students. Psychosomatics. 1988;29(4):404–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(88)72341-5.

Cohen M, Khalaila R. Saliva pH as a biomarker of exam stress and a predictor of exam performance. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(5):420–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.07.003.

Diebig M, Li J, Forthmann B, Schmidtke J, Muth T, Angerer P. A three-wave longitudinal study on the relation between commuting strain and somatic symptoms in university students: exploring the role of learning-family conflicts. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00702-7.

Dighriri Y, Akkur M, Alharbi S, Madkhali N, Matabi K, Mahfouz M. Prevalence and associated factors of neck, shoulder, and low-back pains among medical students at Jazan University, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(12):3826. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_721_19.

Dodin Y, Obeidat N, Dodein R, Seetan K, Alajjawe S, Awwad M, et al. Mental health and lifestyle-related behaviors in medical students in a Jordanian University, and variations by clerkship status. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):1–14.

El-Gilany AH, Amro M, Eladawi N, Khalil M. Mental health status of medical students: a single faculty study in Egypt. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207(5):348–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000970.

Esquerda M, Garcia-Estañ J, Ruiz-Rosales A, Garcia-Abajo JM, Millan J. Academic climate and psychopathological symptomatology in Spanish medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):Article1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04811-2.

Feizy F, Sadeghian E, Shamsaei F, Tapak L. The relationship between internet addiction and psychosomatic disorders in Iranian undergraduate nursing students: a cross-sectional study. J Addict Dis. 2020;38(2):164–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1732180.

Fernandes Azevedo AB, Câmara-Souza MB, Dantas IS, de Resende CMBM, Barbosa GAS. Relationship between anxiety and temporomandibular disorders in dental students. CRANIO®. 2017;1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2017.1361053.

Fino E, Martoni M, Russo PM. Specific mindfulness traits protect against negative effects of trait anxiety on medical student wellbeing during high-pressure periods. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(3):1095–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10039-w.

Gallas S, Knaz H, Methnani J, Maatallah Kanzali M, Koukane A, Bedoui MH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of functional gastrointestinal disorders in early period medical students: a pilot study in Tunisia. Libyan J Med. 2022;17(1):2082029. https://doi.org/10.1080/19932820.2022.2082029.

Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Bonneau RH, Malarkey W, Kennedy S, Hughes J. Stress-induced modulation of the immune response to recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Psychosom Med. 1992;54(1):22–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199201000-00005.

Gorter R, Freeman R, Hammen S, Murtomaa H, Blinkhorn A, Humphris G. Psychological stress and health in undergraduate dental students: fifth year outcomes compared with first year baseline results from five European dental schools. Eur J Dent Educ. 2008;12(2):61–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0579.2008.00468.x.

Goweda R, Alshinawi MA, Janbi BM, Idrees UYM, Babukur RM, Alhazmi HA, et al. Somatic symptom disorder among medical students in Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah Al-Mukarramah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. World Fam Med J Middle East J Fam Med. 2022;20(5). https://doi.org/10.5742/MEWFM.2022.9525030.

Hulsman RL, Pranger S, Koot S, Fabriek M, Karemaker JM, Smets EMA. How stressful is doctor–patient communication? Physiological and psychological stress of medical students in simulated history taking and bad-news consultations. Int J Psychophysiol. 2010;77(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.04.001.

Inshyna NM, Chorna IV. Medical students’ mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Perspekt. 2024;29(1):158–63. https://doi.org/10.26641/2307-0404.2024.1.301146.

Ivashchenko D, Yashina Y, Voznesenskaya T. State anxiety, degree of autonomic symptoms in medical students in various situations during studying process in correspondence to gender. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(Suppl 1):1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(13)76374-0.

Jamil SD, Kaya B, Ay MK, Gökmen AY, Şensazli B, ğlan MK, et al. Somatisation status and associated variables in final-year medical students at a public university, in Istanbul, Türkiye. N Z Med Stud J. 2024;37:16–20. https://doi.org/10.57129/001c.122991.

Kurokawa K, Tanahashi T, Murata A, Akaike Y, Katsuura S, Nishida K, et al. Effects of chronic academic stress on mental state and expression of glucocorticoid receptor and β isoforms in healthy Japanese medical students. Stress. 2011;14(4):431–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2011.555930.

Le JT, Li XR, Huang CC, Dong X, Agrawal H. The correlation between perceived stress and skin-picking in medical students. J Psychosom Res. 2024;179:111651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2024.111651.

Lei J, Jin H, Shen S, Li Z, Gu G. Influence of clinical practice on nursing students’ mental and immune-endocrine functions. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:392–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12272.

Lloyd C, Gartrell NK. Psychiatric symptoms in medical students. Compr Psychiatry. 1984;25(6):552–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440X(84)90036-1.

Lloyd C, Musser LA. Psychiatric symptoms in dental students. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198902000-00001.

Lv S, Chang T, Na S, Lu L, Zhao E. Association between negative life events and somatic symptoms: a mediation model through self-esteem and depression. Behav Sci. 2023;13(3):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030243.

Majeed F, Masood SH, BiBi R, Ali SMM, Najeeb T, Atif A. Perceived stress and its effect on the cardio-respiratory system in first-year medical students. Prof Med J. 2023;30(03):398–405. https://doi.org/10.29309/TPMJ/2023.30.03.7378.

Medisauskaite A, Silkens MEWM, Rich A. A national longitudinal cohort study of factors contributing to UK medical students’ mental ill-health symptoms. Gen Psychiatry. 2023;36(2):e101004. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2022-101004.

Mosley TH, Perrin SG, Neral SM, Dubbert PM, Grothues CA, Pinto BM. Stress, coping, and well-being among third-year medical students. Acad Med. 1994;69(9):765–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199409000-00024.

Neubauer V, Gächter A, Probst T, Brühl D, Dale R, Pieh C, et al. Stress factors in veterinary medicine—a cross-sectional study among veterinary students and practicing vets in Austria. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11:1389042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2024.1389042.

Olvera Alvarez HA, Provencio-Vasquez E, Slavich GM, Laurent JGC, Browning M, McKee-Lopez G, et al. Stress and health in nursing students: the nurse engagement and wellness study. Nurs Res. 2019;68(6):453–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000383.

Pikó B. Frequency of common psychosomatic symptoms and its influence on self-perceived health in a Hungarian student population. Eur J Public Health. 1997;7(3):243–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/7.3.243.

Rocha CO, de Peixoto M, de Resende RF, Alves CMBM, de Oliveira AC, de Barbosa AGR. Psychosocial aspects and temporomandibular disorders in dental students. Orofac Pain. 2017;48(3):241–9.

Ruzhenkova VV, Ruzhenkov VA, Gomelyak JN, Efremova OA. Psychopharmacotherapy for somatoform autonomic dysfunction in students-medicans 1 course. Indo Am J Pharm Sci. 2018;5(7). https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1324401.

Samarah OQ, Maden HA, Sanwar BO, Farhad AP, Alomoush F, Alawneh A, et al. Musculoskeletal pain among medical students at two Jordanian universities. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2023;36(2):429–36. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-220065.

Scheuch K, Pietuschka WD, Hentschel E, Winiecki P, Gruber G. Physiological and psychological response to a three-month mental strain period in students. Act Nerv Super. 1988;30(3):169–73.

Sekas G, Wile MZ. Stress-related illnesses and sources of stress: Comparing, -Ph MD. D., M.D., and Ph.D. students. J Med Educ. 1980;55 :440-446

Smith DR, Wei N, Ishitake T, Wang RS. Musculoskeletal disorders among Chinese medical students. Kurume Med J. 2005;52(4):139–46. https://doi.org/10.2739/kurumemedj.52.139.

Sohrabi MR, Karimi HR, Malih N, Keramatinia AA. Mental health status of medical students: a cross-sectional study. Soc Determinants Health. 2015;1(2):81–8.

Srivastava KC, Shrivastava D, Khan ZA, Nagarajappa AK, Mousa MA, Hamza MO, et al. Evaluation of temporomandibular disorders among dental students of Saudi Arabia using diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD): a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01578-0.

Tan YM, Goh KL, Muhidayah R, Ooi CL, Salem O. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in young adult malaysians: a survey among medical students. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(12):1412–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03212.x.

Tang W, Kang Y, Xu J, Li T. Associations of suicidality with adverse life events, psychological distress and somatic complaints in a Chinese medical student sample. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(4):635–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00523-4.

Tecles F, Fuentes-Rubio M, Tvarijonaviciute A, Martínez-Subiela S, Fatjó J, Cerón JJ. Assessment of stress associated with an oral public speech in veterinary students by salivary biomarkers. J Vet Med Educ. 2014;41(1):37–43. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0513-073R1.

Tocto-Solis K, Muñoz Arteaga EC, Fiestas-Cordova J, Rodriguez-Saldaña CA. Association between level of anxiety and degree of psychosomatic features in medical students at a private university in Northern Peru. Salud Ment. 2023;46(2):55–9. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2023.008.

Vage A, Gormley G, Hamilton PK. The effects of controlled acute psychological stress on serum cortisol and plasma metanephrine concentrations in healthy subjects. Ann Clin Biochem. 2024(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/00045632241301618.

Vitaliano PP, Maiuro RD, Russo J, Mitchell ES, Carr JE, Van Citters RL. A biopsychosocial model of medical student distress. J Behav Med. 1988;11(4):311–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00844933.

Weber J, Heming M, Apolinário-Hagen J, Liszio S, Angerer P. Comparison of the perceived stress reactivity scale with physiological and self-reported stress responses during ecological momentary assessment and during participation in a virtual reality version of the Trier social stress test. Biol Psychol. 2024;186:108762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2024.108762.

Wege N, Muth T, Li J, Angerer P. Mental health among currently enrolled medical students in Germany. Public Health. 2016;132:92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.12.014.

Xu S, Ouyang X, Shi X, Li Y, Chen D, Lai Y, et al. Emotional exhaustion and sleep-related worry as serial mediators between sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms in student nurses: A longitudinal analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2020;129:109870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.10987.

Aksoy B, Ozturk L. A randomized controlled trial on the effect of music and white noise listening on anxiety and vital signs during intramuscular injection skill learning. Teach Learn Nurs. 2024;19(1):e52–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2023.08.020.

Alhawatmeh HN, Rababa M, Alfaqih M, Albataineh R, Hweidi I, Abu Awwad A. The benefits of mindfulness meditation on trait mindfulness, perceived stress, cortisol, and C-reactive protein in nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2022;13:47–58. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S348062.

Andrabi M, Mumba M, Mathews J, Rattan J, Scheiner A. The effectiveness of a yoga program on psychological and cardiovascular outcomes of undergraduate nursing students. Holist Nurs Pract. 2023;37(5):E69–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000599.

Artemiou E, Gilbert G, Sithole F, Koster L. The effects of music during a physical examination skills practice: a pilot study. Vet Sci. 2017;4(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci4040048.

Bhagat A, Srivastav S, Malhotra AS, Rohilla R, Sidana AK, Deepak KK. Role of meditation in ameliorating examination stress induced changes in cardiovascular and autonomic functions. Ann Neurosci. 2023;30(3):188–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/09727531231169629.

Brubaker JR, Swan A, Beverly EA. A brief intervention to reduce burnout and improve sleep quality in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):345. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02263-6.

Dai X, Yu D. Analysis of mental health status before and after psychological intervention in response to public health emergencies by medical students: a prospective single-arm clinical trial. Transl Pediatr. 2023;12(3):462–9. https://doi.org/10.21037/tp-23-120.

Eyüboğlu G, Göçmen Baykara Z, Çalışkan N, Eyikara E, Doğan N, Aydoğan S, et al. Effect of music therapy on nursing students’ first objective structured clinical exams, anxiety levels and vital signs: A randomized controlled study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;97:104687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104687.

Gebhart V, Buchberger W, Klotz I, Neururer S, Rungg C, Tucek G, Perkhofer S. Distraction-focused interventions on examination stress in nursing students: effects on psychological stress and biomarker levels. A randomized controlled trial. Distraction Examination Stress. 2020;26:e12788. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12788.

Kumar V, Gudge S, Patil M, Mudbi S, Patil S. Effects of practice of Pranayama on control of life style disorders. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2014;3(31):8712–8. https://doi.org/10.14260/jemds/2014/3111.

Oró P, Esquerda M, Mas B, Viñas J, Yuguero O, Pifarré J. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based programme on perceived stress, psychopathological symptomatology and burnout in medical students. Mindfulness. 2021;12(5):1138–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01582-5.

Ozturk FO, Tezel A. Effect of laughter yoga on mental symptoms and salivary cortisol levels in first-year nursing students: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Pract. 2021;27(2):e12924. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12924.

Valencia R, Anche G, Do Rego Barros G, Arostegui V, Sutaria H, McAllister E, et al. Stressbusters: a pilot study investigating the effects of OMT on stress management in medical students. J Osteopath Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2024-0020.

Jansson-Frojmark M, Harvey AG, Lundh LG, Norell-Clarke A, Linton SJ. Psychometric properties of an insomnia-specific measure of worry: the anxiety and preoccupation about sleep questionnaire. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(1):65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2010.538432.

Serpa AL, de O, Costa DS, Ferreira CM, Pinheiro MI, Diaz AP, de Paula JJ, et al. Psychometric properties of the brief symptom inventory support the hypothesis of a general psychopathological factor. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021;44:e20210207. https://doi.org/10.47626/2237-6089-2021-0207.

Igbokwe D. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Enugu somatization scale. IFE PsychologIA . 2011 ;;19(1). Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ifep/article/view/64598. Cited 2024 Jan 9.

Moreta-Herrera R, Dominguez-Lara S, Vaca-Quintana D, Zambrano-Estrella J, Gavilanes-Gómez D, Ruperti-Lucero E, et al. Psychometric properties of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) in Ecuadorian college students. Psihol Teme. 2021;30(3):573–90. https://doi.org/10.31820/pt.30.3.9.

Williams JW, Stellato CP, Cornell J, Barrett JE. The 13- and 20-item Hopkins symptom checklist depression scale: psychometric properties in primary care patients with minor depression or dysthymia. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2004;34(1):37–50. https://doi.org/10.2190/U1B0-NKWC-568V-4MAK.

Aldhabi R, Albadi M, Kahraman T, Alsobhi M. Cross-cultural adaptation, validation and psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire in office working population from Saudi Arabia. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2024;72:103102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2024.103102.

Han C, Pae C-U, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Kim KW, Joe S-H, et al. Psychometric properties of the patient health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) for measuring the somatic symptoms of psychiatric outpatients. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):580–5. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.580.

Farahi S, Naziri G, Davodi A, Fath N. Investigation of psychometric properties of Psychosomatic Complaints Scale among individuals with Somatic Symptom Disorder. Int J Appl Behav Sci. 2023;10(2):2. https://doi.org/10.22037/ijabs.v10i2.39882.

Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of a screening instrument (PHQ-15) for somatization syndromes in the general population. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):91. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-91.

Attanasio V, Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, Arena JG. Psychometric properties of the SUNYA revision of the psychosomatic symptom checklist. J Behav Med. 1984;7(2):247–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00845390.

Slavin-Mulford J, Perkey H, Blais M, Stein M, Sinclair SJ. External validity of the symptom Assessment-45 questionnaire (SA-45) in a clinical sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:205–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.12.007.

Smith JK, Józefowicz RF. Diagnosis and treatment of somatoform disorders. Neurol Clin Pract. 2012;2(2):94–102. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0b013e31825a6183.

Fabião C, Silva M, Barbosa A, Fleming M, Rief W. Assessing medically unexplained symptoms: evaluation of a shortened version of the SOMS for use in primary care. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-34.

Gierk B, Kohlmann S, Kroenke K, Spangenberg L, Zenger M, Brähler E, et al. The somatic symptom scale–8 (SSS-8): a brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):399. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12179.

Hagquist C. Psychometric properties of the psychosomatic problems scale: a Rasch analysis on adolescent data. Soc Indic Res. 2008;86(3):511–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9186-3.

Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR). Constructivism Hum Sci. 2003;8(2):73–107.

Guidotti S, Coscioni G, Pruneti C. Impact of Covid-19 on mental health and the role of personality: Preliminary data from a sample of young Italian students. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2022;10(3). Available from: https://cab.unime.it/journals/index.php/MJCP/article/view/3549. Cited 2025 Jul 9.

Alnaser MZ, Alotaibi N, Nadar MS, Manee F, Alrowayeh HN. Manifestation of generalized anxiety disorder and its association with somatic symptoms among occupational and physical therapists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.891276.

Andela M. Burnout, somatic complaints, and suicidal ideations among veterinarians: development and validation of the veterinarians stressors inventory. J Vet Behav. 2020;37:48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2020.02.003.

Guidotti S, Fiduccia A, Pruneti C. Giants with feet of clay: perfectionism, type A behavior, emotional stability, and gender as predictors of university students’ mental health. PSE. 2024;16(3):1–9.

Queirolo L, Roccon A, Piovan S, Ludovichetti FS, Bacci C, Zanette G. Psychophysiological wellbeing in a class of dental students attending dental school: anxiety, burnout, post work executive performance and a 24 hours physiological investigation during a working day. Front Psychol . 2024;15. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1344970/full. Cited 2025 Jul 9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.L.S. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, and writing the original draft.J.M.H. contributed to methodology, writing the original draft, and review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sperling, E.L., Hulett, J.M. A scoping review of somatization: characteristics and implications among health profession students. BMC Med Educ 25, 1625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-08221-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-08221-4